Abstract

Aims

Parental hypertension is known to predict high blood pressure (BP) in children. However, the extent to which risk for hypertension is conferred across multiple generations, notwithstanding the impact of environmental factors, is unclear. Our objective was therefore to evaluate the degree to which risk for hypertension extends across multiple generations of individuals in the community.

Methods and results

We studied three generations of Framingham Heart Study participants with standardized blood pressure measurements performed at serial examinations spanning 5 decades (1948 through 2005): First Generation (n = 1809), Second Generation (n = 2631), and Third Generation (n = 3608, mean age 39 years, 53% women). To capture a more precise estimate of conferrable risk, we defined early-onset hypertension (age <55 years) as the primary exposure. In multinomial logistic regression models adjusting for standard risk factors as well as physical activity and daily intake of dietary sodium, risk for hypertension in the Third Generation was conferred simultaneously by presence of early-onset hypertension in parents [OR 2.10 (95% CI, 1.66–2.67), P < 0.001] as well as in grandparents [OR 1.33 (95% CI, 1.12–1.58), P < 0.01].

Conclusion

Early-onset hypertension in grandparents raises the risk for hypertension in grandchildren, even after adjusting for early-onset hypertension in parents and lifestyle factors. These results suggest that a substantial familial predisposition for hypertension exists, and this predisposition is not identical when assessed from one generation to the next. Additional studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying transgenerational risk for hypertension and its clinical implications.

Keywords: Hypertension, Blood pressure, Heritability, Genetics, Environment

Introduction

Hypertension is a major cardiovascular risk factor that has multiplicative and cumulative effects on the risk of cardiovascular events.1,2 Hypertension is generally considered a complex disease trait that arises from a combination of both genetic predisposition and environmental exposures, including dietary and exercise patterns. Blood pressure, itself, also appears to be causally associated with the rate of rise in blood pressure over time.3 Several lines of evidence argue for the possibility that hypertension is, in fact, predominantly the result of environmental determinants. In tribal populations living in remote non-Westernized areas of the world, where routine dietary salt intake is absent, typical age-related elevations in blood pressure (BP) are not seen.4,5 In Westernized populations, large genetic studies have identified variants associated with BP but these genetic markers account for only a small proportion of variation in BP and risk for hypertension.6,7 In contrast, observations from twin studies would argue that there is actually a very prominent heritable component underlying hypertension risk that has yet to be fully elucidated.8,9 This ‘heritability gap’ in variance estimated by twin studies on the one hand, and population studies on the other hand, has led to persistent confusion regarding the extent to which hypertension is truly heritable.

To further clarify the role of heredity on hypertension risk in the community, we conducted an investigation using uniquely available longitudinal data from the family-based Framingham Heart Study and assessed the extent to which risk for hypertension is conferred across multiple generations of individuals in the community. For this investigation, we used objectively ascertained BP measurements collected from serial examinations attended by a relatively homogenous population of three generations of Framingham participants over a span of 5 decades. We specifically focused our analyses on the extent to which predisposition for hypertension was shared between generations separated by more than 1 degree, wherein the potentially shared effects of environmental factors are reduced.

Methods

Study sample

The First Generation cohort (i.e. grandparents) of the Framingham Heart Study included 5209 adults in Framingham, MA who were enrolled in a longitudinal community-based study, wherein they underwent biennial examinations since 1948. The Second Generation cohort (i.e. parents), includes 5124 children (and their spouses) of the First Generation cohort, who have been re-examined 8 years after the first examination in 1971 and then every 4 years thereafter. The Third Generation cohort includes 4095 individuals who had at least 1 parent in the Second Generation study and attended a baseline examination in 2002–2005. The characteristics and study protocols of all three cohorts have been published previously.10–12 Information on living participants’ last location of residence is continuously updated at the examinations and though telephone and mail follow-up. All study protocols were approved by Boston University Medical Center’s institutional review board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

To examine hypertension risk across generations, we focused our analyses on ‘early-onset’ hypertension (i.e. onset prior to age 55 years as in previous publications) as a distinct form of hypertension that could be discerned from the standardized BP measurement data available from the parents and grandparents of the participants in our study sample.13,14 For our Third Generation participant study sample, directly measured BP data on 1909 grandparents and 2918 parents were available, and we excluded data for parents (n = 64) or grandparents (n = 5) who did not attend any follow-up examinations. We also excluded parental or grandparental data if the age of onset of hypertension was not defined: e.g. if the grandparent or parent was ≥55 years and had hypertension at the baseline examination, respectively (n = 19 parents, n = 75 grandparents).

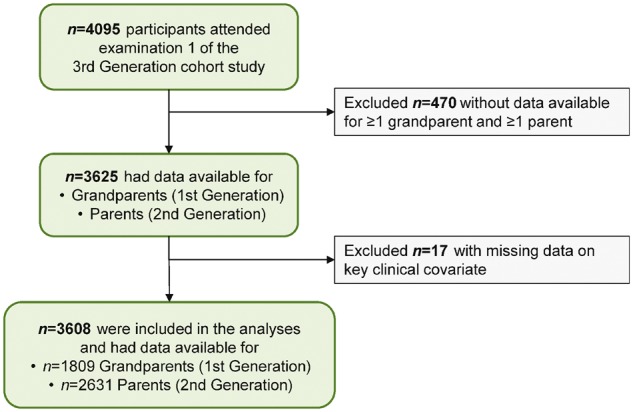

For the present study, we focused on Third Generation cohort participants with parental and grandparental data available and no missing covariates (Figure 1) which led to additional 204 parents and 20 grandparents being excluded. Therefore, our final dataset for analyses included BP measurements collected from 1809 First Generation participants, 2631 Second Generation participants, and 3608 Third Generation participants.

Figure 1.

Individuals included in the main analyses comprised of Third Generation Cohort participants with objectively collected data on parental and grandparental blood pressure measures. Several Third Generation participants may have had a common parent or grandparent.

Clinical assessment and definitions

At each Heart Study examination, participants in all three cohorts provided a medical history, including information on medication use, and underwent a physical examination and laboratory assessment of cardiovascular risk factors.10–12 Information on the use of antihypertensive medication was not available for the first three examinations of First Generation participants (from 1948 through 1956) and we considered these participants as having no antihypertensive medication use. At all examinations, a physician performed 2 sequential BP measurements using a mercury column sphygmomanometer on the left arm of each participant in the seated position, according to a standardized protocol. We considered the BP measurement at a given examination as the mean of the 2 sequentially measured BP values from that clinical assessment. In addition to the assessment of BP and other cardiovascular risk factors, participants in the Third Generation cohort underwent an assessment of physical activity, using a physical activity questionnaire and calculation of the Framingham physical activity index (PAI). Daily dietary sodium intake was assessed using data collected via the validated 131-item Harvard semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire.15,16 The questionnaire was designed to classify individuals according to levels of average daily intake of selected nutrients over the preceding year. We calculated sodium intake from detailed questionnaire data by taking a pre-specified weight assigned to the frequency of reported use and multiplying this value by the sodium intake for the portion size specified for each food item. This method of estimating daily sodium intake has been used in prior studies linking sodium intake with BP and other cardiovascular traits.17,18 Participants reported the number of alcoholic drinks/week (beer, wine, or liquor) consumed per week. We used these data to identify participants as heavy (>7 drinks/week in women and >14 drinks/week in men) vs. non-heavy users of alcohol.19

Exposure and outcome variables

As in other studies of BP assessed across multiple time epochs, we used similar BP thresholds to define hypertension across all examinations in all three cohorts.20 This approach was selected to avoid the imprecision that can be introduced by using self-reported diagnosis data, which can be influenced by temporal changes in standard clinical practice. BP data were available from serial examinations performed in the First Generation cohort from 1948 through 2005 and in the Second Generation cohort from 1971 through 2008. For these participants, given the availability of BP data collected from multiple serial examinations, we defined hypertension as systolic BP ≥140 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medication, on ≥2 consecutively attended examinations.2 Consistent with methods from prior studies, we applied this definition to reduce variation based on only 1 measurement and to represent a durable change in BP.13 Also consistent with methods from prior studies, we defined onset of hypertension as the first examination at which criteria for hypertension was met.13,21 To capture a relatively specific measure of familial hypertension risk exposure, we identified First and Second Generation participants who developed ‘early-onset’ of hypertension prior to age 55 years.

For Third Generation participants, we examined data from only a single baseline examination. Thus, the presence of hypertension in the Third Generation, as an outcome variable, was based on criteria met at this single time point. This approach allowed for predictor variables to be consistently defined, and for the outcome variable to also be internally consistently defined, both according to the current European hypertension guidelines.2 Specifically, in the Third Generation, presence of hypertension was defined as systolic BP ≥140 or diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg or antihypertensive medication use; and, presence of normal/high normal BP was defined as systolic BP 120–139 or diastolic BP 80–89 mmHg (henceforth referred to as normal BP) in Third Generation participants at their first examination.2 We also included normal BP as an outcome, given that that recent trial results have led to continued discussions in the field regarding the extent to which thresholds and targets for hypertension treatment should be lower than those proposed in current guidelines.22

Statistical methods

We examined characteristics of Third Generation participants, categorized by early-onset hypertension status in parents and in grandparents, and by their own BP status: optimal BP, normal BP, and hypertension. We compared participants’ characteristics using χ2 tests for categorical variables and by analysis of variance for continuous variables, except for dietary sodium intake (Kruskal–Wallis test). We assessed the trend in prevalence of normal BP or hypertension in groups by parental and grandparental early-onset hypertension status using the Cochran–Armitage trend test. We analysed the simultaneous association of First Generation (i.e. grandparental) and Second Generation (i.e. parental) early-onset hypertension with presence of hypertension or normal BP in the Third Generation (with optimal BP as the referent group) using multinomial logistic regression models including mixed effects (PROC GLIMMIX) to account for correlation among siblings. In a second step, we also included First and Second Generation late-onset hypertension in the models. We considered both the number and fraction of grandparents and parents with early-onset and late-onset hypertension as the primary exposure variables and we consider BP level in the Third Generation as the outcome variable. In a sensitivity analysis, we used continuous systolic and diastolic BP, instead of BP categories, as outcome variables and adjusted for correlation among siblings using generalized estimating equations. We adjusted all analyses for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, total number of grandparents in the First Generation cohort, and total number of parents in the Second Generation cohort. We did not include diabetes status as a covariate in the main models given its extremely low prevalence at baseline (2.8%). In secondary analyses, we additionally adjusted for measures of physical activity (PAI), alcohol use, and log-transformed dietary sodium intake. We also used an interaction term of sex by number of parents (or grandparents) with early onset hypertension to test for effect modification by sex. The null hypothesis was rejected for 2-sided P-values <0.05. We performed all analyses were performed with SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

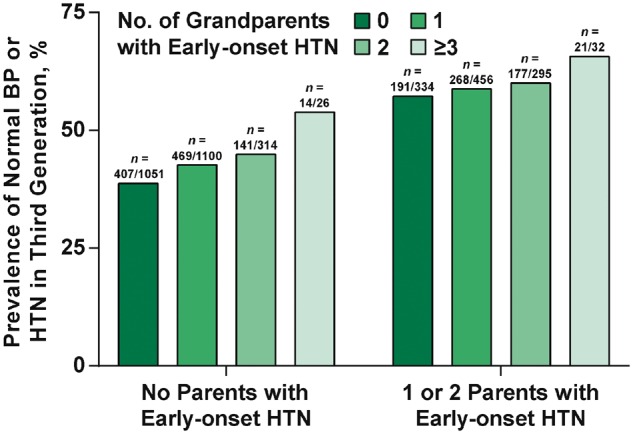

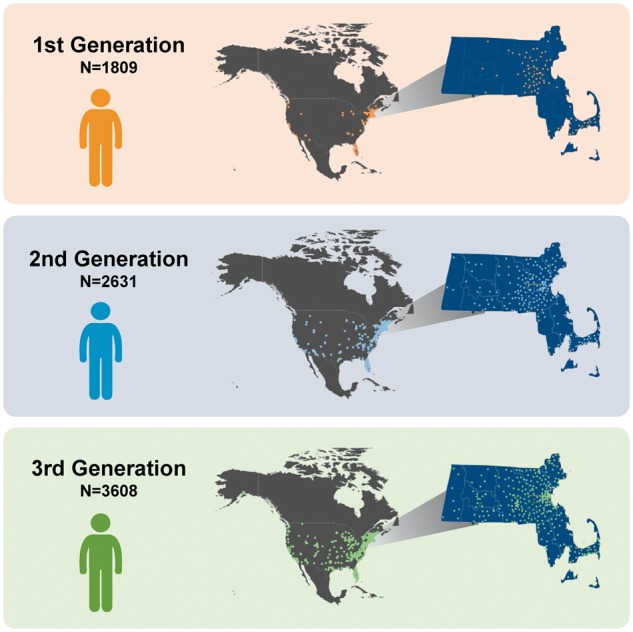

Mean age of the Third Generation study sample was 39.4 (8.5) years and 53% were women. Characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1 by categories defined according to parental and grandparental hypertension status. The groups differed slightly in terms of age, body mass index, total and HDL cholesterol, and more markedly in terms of systolic and diastolic BP. An increasing trend in normal BP and hypertension, and a decreasing trend in optimal BP, was seen across groups. As shown in Figure 2, the prevalence of normal BP or hypertension in groups by parental and grandparental early-onset hypertension status increased from 38.7% (no parents or grandparents with early-onset hypertension) to 65.6% (1 or 2 parents and ≥3 grandparents with early-onset hypertension, P for trend <0.001). The last known geographic location of participants from all three generational cohorts (as of November 2016) is reported in Figure 3 and Supplementary material online, Table S1. Only 10% of the Third Generation participants had last reported living in in Framingham.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of the Third Generation cohort participants according to parental and grandparental hypertension status

| Characteristic | No early HTN in parents or grandparents | Early HTN in grandparents, not in parents | Early HTN in parents, not in grandparents | Early HTN in parents and grandparents | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1051 | 1440 | 334 | 783 | |

| Age, years | 40.3 (8.8) | 38.2 (8.2) | 41.6 (8.8) | 39.6 (8.1) | <0.001 |

| Women, % | 56.1 | 51.5 | 53.9 | 51.6 | 0.11 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.5 (5.2) | 26.1 (5.2) | 27.8 (5.7) | 27.9 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| Current smoker, % | 14.5 | 15.3 | 16.2 | 16.1 | 0.77 |

| Serum cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.9 (1.0) | 4.8 (0.9) | 5.0 (1.0) | 4.8 (0.9) | 0.008 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.4) | 0.01 |

| Physical Activity Indexa | 37.5 (8.0) | 37.6 (7.7) | 37.4 (7.5) | 37.5 (8.3) | 0.97 |

| Median dietary sodium, g/dayb | 2.0 (1.6–2.7) | 2.0 (1.6–2.6) | 2.0 (1.6–2.6) | 2.1 (1.6–2.7) | 0.62 |

| Mean systolic BP, mmHg | 114 (13) | 115 (13) | 120 (14) | 120 (15) | <0.001 |

| Mean diastolic BP, mmHg | 74 (9) | 74 (10) | 77 (10) | 78 (10) | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive medication use, % | 7.3 | 7.8 | 14.4 | 14.7 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension status, % | |||||

| Optimal blood pressure (<120/80 mmHg) | 61.3 | 56.7 | 42.8 | 40.5 | |

| Normal BP (120–139/80–89 mmHg) | 25.4 | 29.0 | 31.7 | 34.2 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension (≥140/90 mmHg) | 13.3 | 14.4 | 25.5 | 25.3 |

Values correspond to mean (SD) unless otherwise noted.

HTN, hypertension; HDL, high density lipoprotein; BP, blood pressure.

Available for 3582 participants.

Available for 3343 participants and expressed as median (inter-quartile range).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of normal blood pressure or hypertension in third generation by parental and grandparental early-onset hypertension status. HTN, hypertension; BP, blood pressure.

Figure 3.

The last reported geographic location of residence, across North America and in the state of Massachusetts for all three generations of participants included in the analyses.

When Third Generation participants were compared according to their BP level, certain demographic and clinical characteristics such as male sex, obesity, and hypercholesterolaemia were more prominent among individuals with hypertension and normal BP compared with those with optimal BP as expected (Table 2). Notably, as shown in Table 2, the fraction of parents with early-onset hypertension was significantly higher in Third Generation participants with hypertension and normal BP compared with those with optimal BP (P < 0.001); furthermore, the same trend was seen for the fraction of grandparents with early-onset hypertension (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Third Generation cohort according to hypertension status

| Characteristic | Optimal BP | Normal BP | HTN | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1920 | 1058 | 630 | |

| Age, years | 37.4 (8.1) | 40.2 (8.3) | 44.5 (7.6) | <0.001 |

| Women, % | 65.6 | 37.7 | 40.8 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.9 (4.4) | 27.9 (5.2) | 30.5 (6.4) | <0.001 |

| Current smoker, % | 15.1 | 15.8 | 15.2 | 0.87 |

| Serum cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.7 (0.8) | 5.0 (0.9) | 5.1 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.5 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Physical Activity Indexa | 37.4 (7.4) | 37.9 (8.4) | 37.4 (8.5) | 0.21 |

| Median dietary sodium, g/db | 2.0 (1.6–2.6) | 2.1 (1.6–2.7) | 2.0 (1.5–2.6) | 0.23 |

| Mean systolic BP, mmHg | 107 (7) | 124 (7) | 132 (16) | <0.001 |

| Mean diastolic BP, mmHg | 69 (7) | 80 (6) | 85 (11) | <0.001 |

| Parents | ||||

| Number with data available | 1.09 (0.29) | 1.10 (0.30) | 1.09 (0.28) | 0.74 |

| Number with early-onset HTN | 0.25 (0.45) | 0.36 (0.50) | 0.47 (0.55) | <0.001 |

| Fraction with early-onset HTN | 0.23 (0.41) | 0.33 (0.46) | 0.43 (0.49) | <0.001 |

| Number with late-onset HTN | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.27 (0.46) | 0.25 (0.45) | 0.001 |

| Fraction with late-onset HTN | 0.19 (0.39) | 0.25 (0.42) | 0.23 (0.41) | 0.001 |

| Grandparents | ||||

| Number with data available | 1.82 (0.70) | 1.81 (0.71) | 1.78 (0.71) | 0.44 |

| Number with early-onset HTN | 0.77 (0.75) | 0.88 (0.80) | 0.88 (0.80) | <0.001 |

| Fraction with early-onset HTN | 0.42 (0.40) | 0.49 (0.42) | 0.48 (0.41) | <0.001 |

| Number with late-onset HTN | 0.66 (0.72) | 0.59 (0.70) | 0.58 (0.67) | 0.009 |

| Fraction with late-onset HTN | 0.36 (0.39) | 0.32 (0.38) | 0.34 (0.39) | 0.02 |

Values correspond to mean (SD) unless otherwise noted.

HTN, hypertension; HDL, high density lipoprotein; BP, blood pressure.

Available for 3582 participants.

Available for 3343 participants and expressed as median (inter-quartile range). Number refers to their absolute number of parents or grandparents with hypertension and data available (range from 0 to 4 for grandparents and from 0 to 2 for parents). Fraction is defined as the number of grandparents or parents with hypertension divided by the number of grandparents or parents with data available (range from 0 to 1.00). Certain parental and grandparental individuals may have been included more than once across different columns of data due to sibships and cousinships.

In multivariable-adjusted analyses, a greater number of parents and grandparents with early-onset hypertension was associated with an increased odds of normal BP and hypertension in the Third Generation cohort (P < 0.001 for all, Table 3). When the number of parents and grandparents with late-onset hypertension were included in the same model, early-onset hypertension in parents and early-onset hypertension in grandparents remained significantly associated with hypertension in the Third Generation participants (Table 3). In contrast, late-onset hypertension in parents or grandparents was not consistently related to hypertension status in the Third Generation (Table 3). We observed similar results when systolic and diastolic BP in the Third Generation were used as continuous outcome variables, and when the fractions, instead of numbers, of parents and grandparents were included as the primary exposure variables in the same models (Table 4 and Supplementary material online, Table S2). In a secondary analysis focused on a subset of 3317 participants with all covariates available, results were also similar in models additionally adjusting for alcohol use, physical activity, represented by the PAI, and daily dietary intake of sodium (Supplementary material online, Table S3). We also tested for effect modification by Third Generation sex and we observed no significant sex-interaction impacting the relationship of parental or grandparental early-onset hypertension on Third Generation hypertension status (P > 0.94).

Table 3.

Association of parental and grandparental hypertension with status in the Third Generation cohort

| Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Optimal BP (n = 1920) | Normal BP (n = 1058) | HTN (n = 630) |

| Model 1: Number of parents or grandparents with early-onset HTN | |||

| 1-Parent increase in number of parents with early-onset HTN | 1.00 | 1.52 (1.27–1.82)* | 2.10 (1.67–2.64)* |

| 1-Grandparent increase in number of grandparents with early-onset HTN | 1.00 | 1.26 (1.12–1.42)* | 1.33 (1.13–1.56)* |

| Model 2: Number of parents or grandparents with early- and late-onset HTN | |||

| 1-Parent increase in number of parents with early-onset HTN | 1.00 | 1.72 (1.42–2.08)* | 2.22 (1.72–2.86)* |

| 1-Grandparent increase in number of grandparents with early-onset HTN | 1.00 | 1.24 (1.05–1.46)*** | 1.38 (1.11–1.73)** |

| 1-Parent increase in number of parents with late-onset HTN | 1.00 | 1.44 (1.16–1.78)* | 1.21 (0.91–1.61) |

| 1-Grandparent increase in number of grandparents with late-onset HTN | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.85–1.20) | 1.09 (0.86–1.38) |

Numbers of parents and grandparents were simultaneously included in the models. Both models adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, number of parents in the Second Generation Cohort, and number of grandparents in First Generation Cohort.

BP, blood pressure; HTN, hypertension.

P < 0.001,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.05.

Table 4.

Association of parental and grandparental hypertension with systolic and diastolic blood pressure in the Third Generation cohort

| Beta ± standard error |

||

|---|---|---|

| Model | Systolic BP | Diastolic BP |

| Model 1: Number of parents or grandparents with early-onset HTN | ||

| 1-Parent increase in number of parents with early-onset HTN | 3.26 ± 0.50* | 2.22 ± 0.34* |

| 1-Grandparent increase in number of grandparents with early-onset HTN | 0.94 ± 0.33** | 0.82 ± 0.23* |

| Model 2: Number of parents or grandparents with early- and late-onset HTN | ||

| 1-Parent increase in number of parents with early-onset HTN | 3.72 ± 0.53* | 2.47 ± 0.37* |

| 1-Grandparent increase in number of grandparents with early-onset HTN | 1.24 ± 0.45** | 1.01 ± 0.30* |

| 1-Parent increase in number of parents with late-onset HTN | 1.55 ± 0.57** | 0.85 ± 0.40*** |

| 1-Grandparent increase in number of grandparents with late-onset HTN | 0.64 ± 0.46 | 0.38 ± 0.31 |

Numbers of parents and grandparents were simultaneously included in the models. Both models adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, number of parents in the Second Generation Cohort, and number of grandparents in First Generation Cohort.

BP, blood pressure; HTN, hypertension.

P < 0.001,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.05.

Discussion

In this study of three generations of Framingham Heart Study participants with objectively measured BP data, a predisposition for hypertension was conferred not only from parent to child but also from grandparent to grandchild. Specifically, we observed that a history of early-onset hypertension in grandparents was associated with the presence of hypertension in a grandchild, even after adjusting for hypertension status in parents and lifestyle factors such as dietary salt intake and physical activity.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the cumulative impact of objectively and uniformly ascertained parental and grandparental hypertension on the prevalence of hypertension in offspring. A handful of prior studies have sought to examine the effects of a particular genetic exposure on risk for a given disease across multiple generations. Accordingly, there are data suggesting that habitual smoking,23,24 depression,25 obesity,26 autism,27 hyperlipidaemia,28 and coronary heart disease29 are traits that could be transmitted across up to three generations; however, prior studies have been relatively small in size or limited in the ability to assess the phenotype of interest in uniform manner across multiple generations. With respect to hypertension, in particular, previous studies have consistently observed parental hypertension in association with risk of incident hypertension in offspring.13,14,30–38 However, only a few questionnaire-based studies have examined the relationship between grandparental hypertension status and risk for hypertension in offspring.14,38 In these survey studies, hypertension in grandparents was modestly associated with hypertension in grandchildren, but the value of grandparental history on top of parental history in assessing hypertension risk was not reported. Importantly, all prior 2- and 3-generation studies of hypertension risk have relied on offspring report of parental and grandparental hypertension status, given lack of objectively collected BP measurements, raising the possibility of biased estimates.39 Therefore, the present study extends the findings of previous work by using objectively collected BP data and demonstrating that a predisposition for developing hypertension is conferred across multiple generations, even after adjusting for parental history and lifestyle factors. Furthermore, this predisposition seems to be more strongly related to early-onset than late-onset hypertension in parents and grandparents.

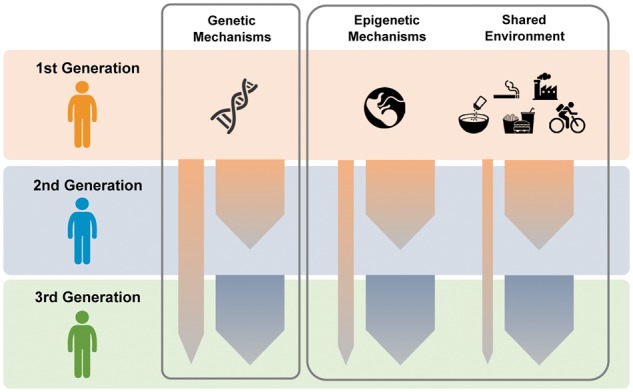

Our main results indicate that a grandparental (i.e. 2nd degree generational) effect on hypertension risk persists on top of the expected parental (i.e. 1st degree generational) effect. There are several possible explanations for this finding that warrant further research. We did observe that the parental effect was stronger than the grandparental effect, but only by a small degree. It is possible that a larger portion of the parental effect is largely due to shared lifestyle and environmental exposures instead of genetic factors, even though we observed no marked attenuation of the parental history associations when we adjusted for dietary salt intake and physical activity (Figure 4). However, the role of the shared environment in our analyses is likely to have been modest, or at least attenuated, over time given that only 10% of the Third Generation participants reported most recently living in the Framingham area. The observed persistence of the grandparental effect is therefore likely related to the fact that hypertension is indeed a familial trait conferring a substantial degree of heritability that has yet to be well-characterized.40 Notwithstanding the possible effects of rare genes with variable penetrance, our results from a large community-based cohort affirm that the highly prevalent form of hypertension is a complex trait with combinations of common susceptibility alleles likely contributing to its risk. Grandparents may carry common alleles that are also variably penetrant or expressive in offspring and even ‘skip’ generations to grandchildren. Of course, some epigenetic changes are not erased during the production of gametes and can affect the phenotype of subsequent generations through transgenerational effects.41 The ability to precisely quantify genetic vs. non-genetic determinants of high blood pressure remains elusive in human studies. However, taken together, these data suggest that at least some proportion of the heritable risk for hypertension arises from genetic traits with effects that may not be simply diluted when transmitted from one generation to the next, but with effects that persist across generations. It remains possible that certain epigenetic changes are also not erased from one generation to another. Ultimately, the overall cross-generational persistence of the grandparental effect, seen even after adjusting for the parental effect, underscores the magnitude of its heritability in spite of potentially shared environmental factors, for which contributions to risk are likely reduced across multiple generations (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Transmission of hypertension risk across generations. Our findings suggest that a predisposition for developing hypertension persists across generations with a proportion of risk that is passed down from grandparent to grandchild, notwithstanding the traits that are passed down from parent to child. Further studies are needed to investigate the relative importance of contributors to hypertension risk that persist across generations.

Notwithstanding the specific strengths of the current study, including the community-based family structure with objective BP measurements and longitudinal data available for 3 generations of participants, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations. First, the follow-up intervals in the First Generation and Second Generation cohorts differed, as First Generation participants underwent biennial examinations whereas their offspring were re-examined approximately every 4 years. Thus, the resolution of BP data collected over time was higher in the First- compared with Second Generation participants. However, because we did not pool cohort data for any analyses, this difference in follow-up intervals is not likely to have markedly influenced the main results. Second, BP data were not available for all parents and grandparents. To avoid confounding, we adjusted for the number of parents and grandparents with data available in the models. Furthermore, no relevant differences in results were observed when the fraction of parents or grandparents was used in the models instead of number of parents or grandparent. Third, despite being logistically feasible and validated for population studies, self-report questionnaires do not necessarily provide the most accurate estimate of lifestyle exposures. Although our modelling included all the lifestyle variables available for analyses (i.e. physical activity, sodium intake, and alcohol use), large cohort study designs are typically unable to completely capture all possible lifestyle exposures, causing the possibility of residual confounding to always remain. Fourth, information on the use of antihypertensive medication was not available for the first three examinations attended by First Generation participants from 1948 through 1956. The impact of these missing data on our main results is likely to be modest given that during this historic time period, the rate of antihypertensive medication was <2.5%. We recognize that BP treatment thresholds were relatively liberal during this earlier era of practice (i.e. systolic BP 180 mmHg or diastolic BP 100 mmHg).42 Even when treatment was initiated, the ability of available medications to effectively lower BP below the 140/90 mmHg threshold was also extremely limited during this same time period.43 Fifth, we used prevalence, instead of incidence, of hypertension as the outcome variable in the Third Generation due to the limited number of available serial examinations for this cohort. Nonetheless, the thresholds used to define hypertension did not vary within or between the cohorts although it remains possible that temporal trends in the relative efficacy of hypertension prevention efforts may have influenced our results. We opted to examine hypertension prevalence instead of incidence, given that the latter would have substantially lowered the study sample size and likely introduced bias as a result of excluding all individual with hypertension at baseline. Sixth, our study enrolled adults at baseline, including some persons who had treated hypertension at the outset; our study also included some persons who never developed hypertension over the course of the longitudinal study period. For these reasons, it was not possible to comprehensively analyse age of hypertension onset as a continuous variable. Nonetheless, our use of a dichotomous exposure variable, albeit less precise, was able to capture early-life hypertension onset in analyses that yielded consistent and interpretable results. Finally, because our study sample consisted primarily of white individuals of European descent, the extent to which our results are generalizable to other racial/ethnic groups is unknown.

In summary, our results demonstrate that there exists a predisposition for hypertension that can be conferred not only from parent to child but from grandparent to grandchild. We observed that the association of risk in grandparents with hypertension in grandchildren persisted, in spite of secular trends and inter-generational differences in lifestyle and behaviour, and remained significant in models adjusting for factors such a physical activity and dietary sodium intake. Notwithstanding the impact of environmental determinants, our findings highlight the importance of the genetic contributors to hypertension risk. Our data suggest that ongoing research on the genetics of hypertension may benefit from a greater focus on traits that persist across, as well as within, generations, as such an approach may help to further characterize the ‘missing heritability’ gap and also identify traits that are least likely to be dependent on environment–gene interactions.44 These interactions, however, cannot be reliably examined in our study setting because certain environmental conditions may exert a uniform exposure across different generations, or an exposure may exceed a threshold level in all subjects. The results of our study also suggest that when assessing an individual’s risk for hypertension, more accurate risk stratification could be achieved by considering both parental and grandparental history of hypertension.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the Framingham Heart Study for invaluable contributions to this work.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ellison Foundation (SC), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute’s Framingham Heart Study (Contract No. N01-HC-25195) and HHSN268201500001I (RSV), and the following grants: T32 GM74905 (ELM), R01HL093328 (RSV), R01HL107385 (RSV), R01HL126136 (RSV), R00HL107642 (SC), R01HL131532 (SC), and R01HL134168 (SC).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1. Ference BA, Ference TB, Brook RD, Catapano AL, Ruff CT, Neff DR, Smith GD, Ray KK, Sabatine MS. A naturally randomized trial comparing the effect of long-term exposure to lower LDL-C, lower SBP, or both on the risk of cardiovascular disease. Abstract presented at European Society of Cardiology Meeting 2016, August 29, 2016, Milan, Italy.

- 2. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Bohm M, Christiaens T, Cifkova R, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Galderisi M, Grobbee DE, Jaarsma T, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, Ruilope LM, Schmieder RE, Sirnes PA, Sleight P, Viigimaa M, Waeber B, Zannad F, Redon J, Dominiczak A, Narkiewicz K, Nilsson PM, Burnier M, Viigimaa M, Ambrosioni E, Caufield M, Coca A, Olsen MH, Schmieder RE, Tsioufis C, van de Borne P, Zamorano JL, Achenbach S, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Clement DL, Coca A, Gillebert TC, Tendera M, Rosei EA, Ambrosioni E, Anker SD, Bauersachs J, Hitij JB, Caulfield M, De Buyzere M, De Geest S, Derumeaux GA, Erdine S, Farsang C, Funck-Brentano C, Gerc V, Germano G, Gielen S, Haller H, Hoes AW, Jordan J, Kahan T, Komajda M, Lovic D, Mahrholdt H, Olsen MH, Ostergren J, Parati G, Perk J, Polonia J, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Ryden L, Sirenko Y, Stanton A, Struijker-Boudier H, Tsioufis C, van de Borne P, Vlachopoulos C, Volpe M, Wood DA.. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2013;34:2159–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ference BA, Julius S, Mahajan N, Levy PD, Williams KA S, Flack JM.. Clinical effect of naturally random allocation to lower systolic blood pressure beginning before the development of hypertension. Hypertension 2014;63:1182–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Oliver WJ, Cohen EL, Neel JV.. Blood pressure, sodium intake, and sodium related hormones in the Yanomamo Indians, a “no-salt” culture. Circulation 1975;52:146–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Page LB, Damon A, Moellering RC Jr.. Antecedents of cardiovascular disease in six Solomon Islands societies. Circulation 1974;49:1132–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. International Consortium for Blood Pressure Genome-Wide Association Studies, Ehret GB, Munroe PB, Rice KM, Bochud M, Johnson AD, Chasman DI, Smith AV, Tobin MD, Verwoert GC, Hwang SJ, Pihur V, Vollenweider P, O'Reilly PF, Amin N, Bragg-Gresham JL, Teumer A, Glazer NL, Launer L, Zhao JH, Aulchenko Y, Heath S, Sober S, Parsa A, Luan J, Arora P, Dehghan A, Zhang F, Lucas G, Hicks AA, Jackson AU, Peden JF, Tanaka T, Wild SH, Rudan I, Igl W, Milaneschi Y, Parker AN, Fava C, Chambers JC, Fox ER, Kumari M, Go MJ, van der Harst P, Kao WH, Sjogren M, Vinay DG, Alexander M, Tabara Y, Shaw-Hawkins S, Whincup PH, Liu Y, Shi G, Kuusisto J, Tayo B, Seielstad M, Sim X, Nguyen KD, Lehtimaki T, Matullo G, Wu Y, Gaunt TR, Onland-Moret NC, Cooper MN, Platou CG, Org E, Hardy R, Dahgam S, Palmen J, Vitart V, Braund PS, Kuznetsova T, Uiterwaal CS, Adeyemo A, Palmas W, Campbell H, Ludwig B, Tomaszewski M, Tzoulaki I, Palmer ND, CARDIoGRAM consortium, CKDGen Consortium, KidneyGen Consortium, EchoGen consortium, CHARGE-HF consortium, Aspelund T, Garcia M, Chang YP, O'Connell JR, Steinle NI, Grobbee DE, Arking DE, Kardia SL, Morrison AC, Hernandez D, Najjar S, McArdle WL, Hadley D, Brown MJ, Connell JM, Hingorani AD, Day IN, Lawlor DA, Beilby JP, Lawrence RW, Clarke R, Hopewell JC, Ongen H, Dreisbach AW, Li Y, Young JH, Bis JC, Kahonen M, Viikari J, Adair LS, Lee NR, Chen MH, Olden M, Pattaro C, Bolton JA, Kottgen A, Bergmann S, Mooser V, Chaturvedi N, Frayling TM, Islam M, Jafar TH, Erdmann J, Kulkarni SR, Bornstein SR, Grassler J, Groop L, Voight BF, Kettunen J, Howard P, Taylor A, Guarrera S, Ricceri F, Emilsson V, Plump A, Barroso I, Khaw KT, Weder AB, Hunt SC, Sun YV, Bergman RN, Collins FS, Bonnycastle LL, Scott LJ, Stringham HM, Peltonen L, Perola M, Vartiainen E, Brand SM, Staessen JA, Wang TJ, Burton PR, Soler Artigas M, Dong Y, Snieder H, Wang X, Zhu H, Lohman KK, Rudock ME, Heckbert SR, Smith NL, Wiggins KL, Doumatey A, Shriner D, Veldre G, Viigimaa M, Kinra S, Prabhakaran D, Tripathy V, Langefeld CD, Rosengren A, Thelle DS, Corsi AM, Singleton A, Forrester T, Hilton G, McKenzie CA, Salako T, Iwai N, Kita Y, Ogihara T, Ohkubo T, Okamura T, Ueshima H, Umemura S, Eyheramendy S, Meitinger T, Wichmann HE, Cho YS, Kim HL, Lee JY, Scott J, Sehmi JS, Zhang W, Hedblad B, Nilsson P, Smith GD, Wong A, Narisu N, Stancakova A, Raffel LJ, Yao J, Kathiresan S, O'Donnell CJ, Schwartz SM, Ikram MA, Longstreth WT Jr, Mosley TH, Seshadri S, Shrine NR, Wain LV, Morken MA, Swift AJ, Laitinen J, Prokopenko I, Zitting P, Cooper JA, Humphries SE, Danesh J, Rasheed A, Goel A, Hamsten A, Watkins H, Bakker SJ, van Gilst WH, Janipalli CS, Mani KR, Yajnik CS, Hofman A, Mattace-Raso FU, Oostra BA, Demirkan A, Isaacs A, Rivadeneira F, Lakatta EG, Orru M, Scuteri A, Ala-Korpela M, Kangas AJ, Lyytikainen LP, Soininen P, Tukiainen T, Wurtz P, Ong RT, Dorr M, Kroemer HK, Volker U, Volzke H, Galan P, Hercberg S, Lathrop M, Zelenika D, Deloukas P, Mangino M, Spector TD, Zhai G, Meschia JF, Nalls MA, Sharma P, Terzic J, Kumar MV, Denniff M, Zukowska-Szczechowska E, Wagenknecht LE, Fowkes FG, Charchar FJ, Schwarz PE, Hayward C, Guo X, Rotimi C, Bots ML, Brand E, Samani NJ, Polasek O, Talmud PJ, Nyberg F, Kuh D, Laan M, Hveem K, Palmer LJ, van der Schouw YT, Casas JP, Mohlke KL, Vineis P, Raitakari O, Ganesh SK, Wong TY, Tai ES, Cooper RS, Laakso M, Rao DC, Harris TB, Morris RW, Dominiczak AF, Kivimaki M, Marmot MG, Miki T, Saleheen D, Chandak GR, Coresh J, Navis G, Salomaa V, Han BG, Zhu X, Kooner JS, Melander O, Ridker PM, Bandinelli S, Gyllensten UB, Wright AF, Wilson JF, Ferrucci L, Farrall M, Tuomilehto J, Pramstaller PP, Elosua R, Soranzo N, Sijbrands EJ, Altshuler D, Loos RJ, Shuldiner AR, Gieger C, Meneton P, Uitterlinden AG, Wareham NJ, Gudnason V, Rotter JI, Rettig R, Uda M, Strachan DP, Witteman JC, Hartikainen AL, Beckmann JS, Boerwinkle E, Vasan RS, Boehnke M, Larson MG, Jarvelin MR, Psaty BM, Abecasis GR, Chakravarti A, Elliott P, van Duijn CM, Newton-Cheh C, Levy D, Caulfield MJ, Johnson T.. Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk. Nature 2011;478:103–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kato N, Loh M, Takeuchi F, Verweij N, Wang X, Zhang W, Kelly TN, Saleheen D, Lehne B, Mateo Leach I, Drong AW, Abbott J, Wahl S, Tan ST, Scott WR, Campanella G, Chadeau-Hyam M, Afzal U, Ahluwalia TS, Bonder MJ, Chen P, Dehghan A, Edwards TL, Esko T, Go MJ, Harris SE, Hartiala J, Kasela S, Kasturiratne A, Khor CC, Kleber ME, Li H, Mok ZY, Nakatochi M, Sapari NS, Saxena R, Stewart AF, Stolk L, Tabara Y, Teh AL, Wu Y, Wu JY, Zhang Y, Aits I, Da Silva Couto Alves A, Das S, Dorajoo R, Hopewell JC, Kim YK, Koivula RW, Luan J, Lyytikainen LP, Nguyen QN, Pereira MA, Postmus I, Raitakari OT, Bryan MS, Scott RA, Sorice R, Tragante V, Traglia M, White J, Yamamoto K, Zhang Y, Adair LS, Ahmed A, Akiyama K, Asif R, Aung T, Barroso I, Bjonnes A, Braun TR, Cai H, Chang LC, Chen CH, Cheng CY, Chong YS, Collins R, Courtney R, Davies G, Delgado G, Do LD, Doevendans PA, Gansevoort RT, Gao YT, Grammer TB, Grarup N, Grewal J, Gu D, Wander GS, Hartikainen AL, Hazen SL, He J, Heng CK, Hixson JE, Hofman A, Hsu C, Huang W, Husemoen LL, Hwang JY, Ichihara S, Igase M, Isono M, Justesen JM, Katsuya T, Kibriya MG, Kim YJ, Kishimoto M, Koh WP, Kohara K, Kumari M, Kwek K, Lee NR, Lee J, Liao J, Lieb W, Liewald DC, Matsubara T, Matsushita Y, Meitinger T, Mihailov E, Milani L, Mills R, Mononen N, Muller-Nurasyid M, Nabika T, Nakashima E, Ng HK, Nikus K, Nutile T, Ohkubo T, Ohnaka K, Parish S, Paternoster L, Peng H, Peters A, Pham ST, Pinidiyapathirage MJ, Rahman M, Rakugi H, Rolandsson O, Rozario MA, Ruggiero D, Sala CF, Sarju R, Shimokawa K, Snieder H, Sparso T, Spiering W, Starr JM, Stott DJ, Stram DO, Sugiyama T, Szymczak S, Tang WH, Tong L, Trompet S, Turjanmaa V, Ueshima H, Uitterlinden AG, Umemura S, Vaarasmaki M, van Dam RM, van Gilst WH, van Veldhuisen DJ, Viikari JS, Waldenberger M, Wang Y, Wang A, Wilson R, Wong TY, Xiang YB, Yamaguchi S, Ye X, Young RD, Young TL, Yuan JM, Zhou X, Asselbergs FW, Ciullo M, Clarke R, Deloukas P, Franke A, Franks PW, Franks S, Friedlander Y, Gross MD, Guo Z, Hansen T, Jarvelin MR, Jorgensen T, Jukema JW, Kahonen M, Kajio H, Kivimaki M, Lee JY, Lehtimaki T, Linneberg A, Miki T, Pedersen O, Samani NJ, Sorensen TI, Takayanagi R, Toniolo D, BIOS-consortium, CARDIo GRAMplusCD, LifeLines Cohort Study, InterAct Consortium, Ahsan H, Allayee H, Chen YT, Danesh J, Deary IJ, Franco OH, Franke L, Heijman BT, Holbrook JD, Isaacs A, Kim BJ, Lin X, Liu J, Marz W, Metspalu A, Mohlke KL, Sanghera DK, Shu XO, van Meurs JB, Vithana E, Wickremasinghe AR, Wijmenga C, Wolffenbuttel BH, Yokota M, Zheng W, Zhu D, Vineis P, Kyrtopoulos SA, Kleinjans JC, McCarthy MI, Soong R, Gieger C, Scott J, Teo YY, He J, Elliott P, Tai ES, van der Harst P, Kooner JS, Chambers JC.. Trans-ancestry genome-wide association study identifies 12 genetic loci influencing blood pressure and implicates a role for DNA methylation. Nat Genet 2015;47:1282–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hottenga JJ, Whitfield JB, de Geus EJ, Boomsma DI, Martin NG.. Heritability and stability of resting blood pressure in Australian twins. Twin Res Hum Genet 2006;9:205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harrap SB. Hypertension: genes versus environment. Lancet 1994;344:169–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kannel WB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP.. An investigation of coronary heart disease in families. The Framingham offspring study. Am J Epidemiol 1979;110:281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dawber TR, Meadors GF, Moore FE.. Epidemiological approaches to heart disease: the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health Nations Health 1951;41:279–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Splansky GL, Corey D, Yang Q, Atwood LD, Cupples LA, Benjamin EJ, D'Agostino RB, Fox CS, Larson MG, Murabito JM, O'Donnell CJ, Vasan RS, Wolf PA, Levy D.. The Third Generation Cohort of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Framingham Heart Study: design, recruitment, and initial examination. Am J Epidemiol 2007;165:1328–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang NY, Young JH, Meoni LA, Ford DE, Erlinger TP, Klag MJ.. Blood pressure change and risk of hypertension associated with parental hypertension: the Johns Hopkins Precursors Study. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:643–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hunt SC, Williams RR, Barlow GK.. A comparison of positive family history definitions for defining risk of future disease. J Chronic Dis 1986;39:809–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kannel WB, Sorlie P.. Some health benefits of physical activity. The Framingham Study. Arch Intern Med 1979;139:857–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC.. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol 1992;135:1114–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ascherio A, Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Willett WC, Sacks F, Stampfer MJ.. A prospective study of nutritional factors and hypertension among US men. Circulation 1992;86:1475–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Koning L, Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Hu FB.. Diet-quality scores and the risk of type 2 diabetes in men. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1150–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 8th ed. http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/ (8 March 2017).

- 20. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population-based measurement studies with 19.1 million participants. Lancet 2016;389:37–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Toren P, Margel D, Kulkarni G, Finelli A, Zlotta A, Fleshner N.. Effect of dutasteride on clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia in asymptomatic men with enlarged prostate: a post hoc analysis of the REDUCE study. BMJ 2013;346:f2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. SPRINT Research Group, Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, Snyder JK, Sink KM, Rocco MV, Reboussin DM, Rahman M, Oparil S, Lewis CE, Kimmel PL, Johnson KC, Goff DC, Fine LJ, Cutler JA, Cushman WC, Cheung AK, Ambrosius WT.. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2103–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Escario JJ, Wilkinson AV.. The intergenerational transmission of smoking across three cohabitant generations: a count data approach. J Community Health 2015;40:912–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. El-Amin SE, Kinnunen JM, Ollila H, Helminen M, Alves J, Lindfors P, Rimpela AH.. Transmission of smoking across three generations in Finland. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;13:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Warner V, Weissman MM, Mufson L, Wickramaratne PJ.. Grandparents, parents, and grandchildren at high risk for depression: a three-generation study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999;38:289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hancock KJ, Mitrou F, Shipley M, Lawrence D, Zubrick SR.. A three generation study of the mental health relationships between grandparents, parents and children. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Frans EM, Sandin S, Reichenberg A, Langstrom N, Lichtenstein P, McGrath JJ, Hultman CM.. Autism risk across generations: a population-based study of advancing grandpaternal and paternal age. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:516–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kardia SL, Haviland MB, Sing CF.. Correlates of family history of coronary artery disease in children. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:473–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ranthe MF, Petersen JA, Bundgaard H, Wohlfahrt J, Melbye M, Boyd HA.. A detailed family history of myocardial infarction and risk of myocardial infarction—a nationwide cohort study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0125896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Friedman GD, Selby JV, Quesenberry CP Jr, Armstrong MA, Klatsky AL.. Precursors of essential hypertension: body weight, alcohol and salt use, and parental history of hypertension. Prev Med 1988;17:387–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hunt SC, Stephenson SH, Hopkins PN, Williams RR.. Predictors of an increased risk of future hypertension in Utah. A screening analysis. Hypertension 1991;17:969–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shear CL, Burke GL, Freedman DS, Berenson GS.. Value of childhood blood pressure measurements and family history in predicting future blood pressure status: results from 8 years of follow-up in the Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics 1986;77:862–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Burke V, Gracey MP, Beilin LJ, Milligan RA.. Family history as a predictor of blood pressure in a longitudinal study of Australian children. J Hypertens 1998;16:269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Juhola J, Oikonen M, Magnussen CG, Mikkilä V, Siitonen N, Jokinen E, Laitinen T, Wurtz P, Gidding SS, Taittonen L, Seppala I, Jula A, Kähönen M, Hutri-Kahonen N, Lehtimäki T, Viikari JS, Juonala M, Raitakari OT.. Childhood physical, environmental, and genetic predictors of adult hypertension: the cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. Circulation 2012;126:402–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shook RP, Lee DC, Sui X, Prasad V, Hooker SP, Church TS, Blair SN.. Cardiorespiratory fitness reduces the risk of incident hypertension associated with a parental history of hypertension. Hypertension 2012;59:1220–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fava C, Sjögren M, Montagnana M, Danese E, Almgren P, Engström G, Nilsson P, Hedblad B, Guidi GC, Minuz P, Melander O.. Prediction of blood pressure changes over time and incidence of hypertension by a genetic risk score in Swedes. Hypertension 2013;61:319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fava C, Sjögren M, Olsson S, Lovkvist H, Jood K, Engström G, Hedblad B, Norrving B, Jern C, Lindgren A, Melander O.. A genetic risk score for hypertension associates with the risk of ischemic stroke in a Swedish case-control study. Eur J Hum Genet 2015;23:969–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ranasinghe P, Cooray DN, Jayawardena R, Katulanda P.. The influence of family history of hypertension on disease prevalence and associated metabolic risk factors among Sri Lankan adults. BMC Public Health 2015;15:576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bensen JT, Liese AD, Rushing JT, Province M, Folsom AR, Rich SS, Higgins M.. Accuracy of proband reported family history: the NHLBI Family Heart Study (FHS). Genet Epidemiol 1999;17:141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Munoz M, Pong-Wong R, Canela-Xandri O, Rawlik K, Haley CS, Tenesa A.. Evaluating the contribution of genetics and familial shared environment to common disease using the UK Biobank. Nat Genet 2016;48:980–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nadeau JH. Transgenerational genetic effects on phenotypic variation and disease risk. Hum Mol Genet 2009;18:R202–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mosterd A, D'Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Sytkowski PA, Kannel WB, Grobbee DE, Levy D.. Trends in the prevalence of hypertension, antihypertensive therapy, and left ventricular hypertrophy from 1950 to 1989. N Engl J Med 1999;340:1221–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moser M. Historical perspectives on the management of hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2006;8:15–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Simon PH, Sylvestre MP, Tremblay J, Hamet P.. Key Considerations and Methods in the Study of Gene-Environment Interactions. Am J Hypertens 2016;29:891–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.