Abstract

Testing drugs for anti-aging effects has historically been conducted in mouse life-span studies, but are costly and time consuming, and more importantly, difficult to recapitulate in humans. In addition, life-span studies in mice are not well suited to testing drug combinations that target multiple factors involved in aging. Additional paradigms for testing therapeutics aimed at slowing aging are needed. A new paradigm, designated as the Geropathology Grading Platform (GGP), is based on a standardized set of guidelines developed to detect the presence or absence of low-impact histopathological lesions and to determine the level of severity of high-impact lesions in organs from aged mice. The GGP generates a numerical score for each age-related lesion in an organ, summed for total lesions, and averaged over multiple mice to obtain a composite lesion score (CLS). Preliminary studies show that the platform generates CLSs that increase with the age of mice in an organ-dependent manner. The CLSs are sensitive enough to detect changes elicited by interventions that extend mouse life span, and thus help validate the GGP as a novel tool to measure biological aging. While currently optimized for mice, the GGP could be adapted to any preclinical animal model.

Keywords: Geropathology Grading Platform, Aging, Aging lesions in mice, Preclinical drug testing, Anti-aging therapeutics

Currently, the preclinical testing of therapeutic interventions to slow aging is largely done by measuring life span as an outcome in mice. However, this is relatively costly and time consuming. Furthermore, life span cannot be used as an end point in human clinical trials, because the cost becomes prohibitive. In addition, life-span studies in mice are too long and costly to efficiently test drug combinations that target multiple aging pathways. Thus, new end points and methods are needed for preclinical testing or screening of therapeutics aimed at slowing aging.

To address this need, a new paradigm, designated as the Geropathology Grading Platform (GGP) (1), was recently developed by the Geropathology Grading Committee, an active component of the Geropathology Research Network funded by an NIA R24 grant (Warren Ladiges, PI). The committee consists of a chair (Warren Ladiges) and six board-certified veterinary pathologists: Denny Liggitt, DVM, PhD, Department of Comparative Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington; Jessica M. Snyder, DVM, MS, Department of Comparative Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington; Tim Snider, DVM, PhD, Department of Veterinary Pathology, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, Oklahoma; Erby Wilkinson, DVM, PhD, Department of Pathology, University of Michigan, Ann Arber, Michigan; Denise M. Imai, DVM, PhD, Department of Comparative Pathology, University of California, Davis, Davis, California; and Smitha P. S. Pillai, DVM, PhD, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington.

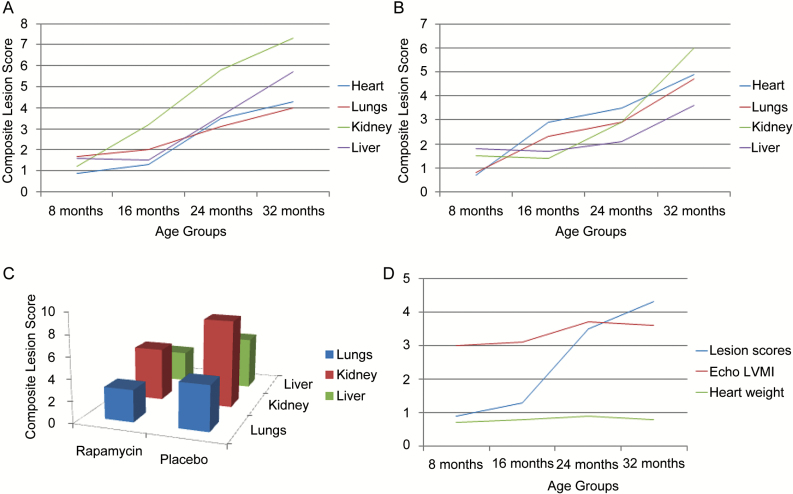

The GGP is based on a standard set of guidelines developed to (i) detect the histological presence or absence of low-impact lesions in multiple organs and (ii) measure the level of severity of high-impact lesions related to aging, in mice (2,3). The platform is designed to generate a numerical score for each lesion in a specific organ, so that a total lesion score is obtained by adding each lesion score for that organ for one mouse. Total lesion scores are averaged between all mice in a specific cohort to obtain a composite lesion score (CLS) for that organ (4). The CLS can then be used to compare response to drug treatment over time, determine effect of alterations in gene expression, or investigate the impact of environmental challenges in a variety of preclinical aging studies. This platform has been used to compare CLS in 8-, 16-, 24-, and 32-month-old male C57BL/6nia (B6) and C57BL/6nia × BALB/cnia F1 (CB6F1) mouse strains. As can be seen in Figure 1A, the CLS in four organs, heart, lungs, kidney, and liver for B6 mice increased in an age-dependent manner as predicted. It is clearly evident that the greatest rate of increase in CLS was between 16 and 24 months. Furthermore, there were differences in the rate of increase of CLS between individual organs. A similar pattern was also seen in CB6F1 mice (Figure 1B) indicating that the age-related increase in CLS was not strain dependent.

Figure 1.

Composite lesion scores generated by the Geropathology Grading Platform in mice change in an age- and drug-dependent manner. (A) Composite lesion scores in four age groups of C57BL/6N male mice increase with increasing age and in an organ-dependent manner, N = 12/cohort. (B) Composite lesion scores in four age groups of CB6F1 male mice increase with increasing age and in an organ-dependent manner, N = 12/cohort. (C) Composite lesion scores are suppressed in 24-month-old C57BL/6 mice after 2 months of oral rapamycin, 42 ppm, N = 6–7/cohort, p ≤ .05. (D) Composite lesion scores in the heart increase in alignment with left ventricular mass index (LVMI) and organ weight as measures of the progression of cardiac decline with increasing age in C57BL/6N mice, N = 12/cohort.

One of the advantages of the GGP as a new drug-testing paradigm is that differences can be seen in CLS in middle-aged mice treated with an anti-aging drug in only several months. For example, the platform was used to compare CLS in B6 mice treated with rapamycin for 2 months, starting treatment at 24 months of age. Microencapsulated rapamycin was delivered in the feed at 42 ppm. As can be seen in Figure 1C, rapamycin-treated mice had significantly lower CLS in multiple organs compared with placebo-treated mice. Experiments with additional anti-aging drugs would help to further validate these initial observations. CLS also correlated well with other measures of age-related decline as shown in an example of cardiac aging in Figure 1D. Left ventricular mass index, quantified by ECHO, is a measure of chronic progressive heart disease and dysfunction. The heart CLS changed more dramatically than the left ventricular mass index over the same period of life, suggesting that CLS may be a very sensitive indicator of age-related cardiac dysfunction. A second example is the age-dependent increase in carpal joint lesions associated with an age-related decrease in grip strength of the front paw (5). These observations help validate the GGP as a way to measure biological aging. This is critical for and accelerates the pace of testing therapeutics targeting aging. Further work is needed to align the GGP with mouse life-span studies, other measures of aging, for example, frailty, and molecular pathology end points that translate easily (6).

The platform can therefore be used in a rapid and sensitive manner to readily test not only single drugs but drug combinations that target different molecular pathways associated with aging. The GGP also reveals which organs are most affected by a particular intervention. This can help guide future clinical trials and what end points should be measured. The GGP will be expanded to additional organs and tissue sets including skeletal muscle, front paw consisting of joints and bone, head consisting of nasal cavity, teeth, eyes, ears, brain and brain stem, and reproductive organs. The GGP Committee is working to finalize grading guidelines for these organ sets in the near future.

Funding

This work was supported by NIA R24 AG047115 (W.L., PI), NIA R01 AG031764 (P.R., PI), NIA P01 AG043376 (L.N.), and presented at the Geropathology Workshop in conjunction with the annual meeting of the American Aging Association in Seattle, Washington, June 2016.

Conflict of Interest

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1. Ladiges W, Ikeno Y, Niedernhofer L, et al. The geropathology research network: an interdisciplinary approach for integrating pathology into research on aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:431–434. doi:10.1093/gerona/glv079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Treuting PM, Linford NJ, Knoblaugh SE, et al. Reduction of age-associated pathology in old mice by overexpression of catalase in mitochondria. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:813–822. PMID:18772461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ladiges W, Ikeno Y, Liggitt D, Treuting PM. Pathology is a critical aspect of preclinical aging studies. Pathobiol Aging Age Relat Dis. 2013;3:22451. doi:10.3402/pba.v3i0.22451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ladiges W. Pathology assessment is necessary to validate translational endpoints in preclinical aging studies. Pathobiol Aging Age Relat Dis. 2016;6:31478. doi:10.3402/pba.v6.31478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ge X, Cho A, Ciol MA, Pettan-Brewer C, Rabinovitch P, Ladiges W. Grip strength is potentially an early indicator of age-related decline in mice. Pathobiol Aging Age Relat Dis. 2016;6:32981. doi:10.3402/pba.v6.32981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Niedernhofer LJ, Kirkland JL, Ladiges W. Molecular pathology endpoints useful for aging studies. Ageing Res Rev. 2016. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2016.09.012 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]