Abstract

Gene expression responses to glucocorticoid (GC) in the hours preceding onset of apoptosis was compared in three clones of human acute lymphoblastic leukemia CEM cells. Between 2 and 20 hr, all three clones showed increasing numbers of responding genes. Each clone had many unique responses, but the two responsive clones showed a group of responding genes in common, different from the resistant clone. MYC levels and the balance of activities between the three major groups of MAPKs are known important regulators of glucocorticoid-driven apoptosis in several lymphoid cell systems. Common to the two sensitive clones were changed transcript levels from genes that decrease amounts or activity of anti-apoptotic ERK/MAPK1 and JNK2/MAPK9, or of genes that increase activity of pro-apoptotic p38/MAPK14. Down-regulation of MYC and several MYC-regulated genes relevant to MAPKs also occurred in both sensitive clones. Transcriptomine comparisons revealed probable NOTCH-GC crosstalk in these cells.

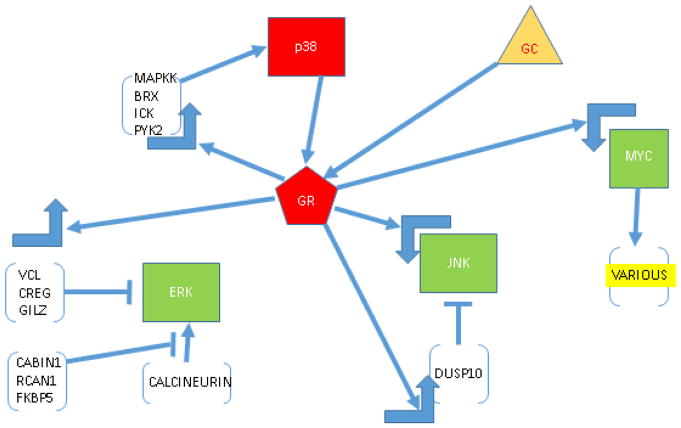

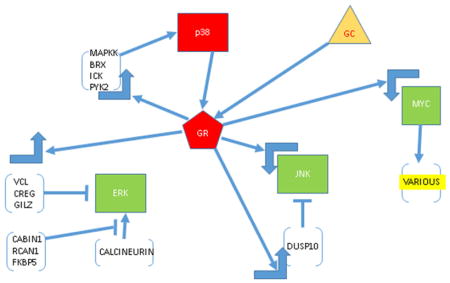

Graphical Abstract

Interactions of GR, MYC and MAPK pathways, from analysis of time course of altered gene regulation in CEM cells. GC (triangle) enters cell and activates GR, which by up- or down-regulating many genes, causes lowered activity and or amounts of antiapoptotic ERK and JNK and enhanced activity of proapoptotic p38. In forward feedback, p38 phosphorylates a specific ser of GR, which further enhances GR activity. GR down-regulates Myc which reduces transcription of JNK and further affects MAPKs via downregulation of various (yellow) other Myc-dependent genes. All arrows indicate direct or indirect regulation. Large right-angle arrows, up or down regulation.. Red indicates increased activity/amount; green, decreased.

1. Introduction

The glucocorticoid (GC)-dependent apoptotic death of lymphoid leukemic cells depends on prolonged prior genomic and proteomic effects, driven by GC activation of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR). GR regulation of gene expression is modulated by other major cell signaling chemicals and pathways, viz. MYC (Yuh and Thompson, 1989, Zhou, Medh and Thompson, 2000, Medh, Wang, Zhou et al., 2001); PKA (Medh, Saeed, Johnson et al., 1998, Zhang and Insel, 2004); nitric oxide (Marchetti, et al. 2005); p53 (Sengupta and Wasylyk, 2004); multiple (Distelhorst, 2002, Webb, Miller, Johnson et al., 2003); AP-1(Karin and Chang, 2001); polyamines (Miller, Johnson, Medh et al., 2002); redox pathway (Makino, Okamoto, Yoshikawa et al., 1996); oxysterols (Johnson, Ayala-Torres, Chan et al., 1997); Erg and AP-1(Chen, Saha, Liu et al., 2013). We have shown in CEM childhood leukemic cells and several other malignant lymphoid cell lines, that the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway strongly influences the outcome of GC-dependent effects (Miller, Webb, Copik et al., 2005). MAPKs ERK and JNK act to protect CEM cells from GC-dependent apoptosis, whereas p38 MAPK enhances the GC apoptotic effect, and a specific activating site on the GR is phosphorylated by p38 MAPK. In CEM and other malignant lymphoid cell lines, the balance between JNK/ERK and p38 strongly affects GC sensitivity (Garza, Miller, Johnson et al., 2009). Herein, we have studied three clones of CEM cells, CEM C7-14, CEM C1-6 and CEM C1-15. All were derived by serial dilution subcloning from our original prototype GR+ sensitive (C7) and resistant (C1) clones (Norman and Thompson, 1977). Subclones C7-14 and C1-15 retain these parental characteristics. Clone C1-6, a spontaneous revertant to sensitivity, is a sister clone to C1-15. Initial gene array comparisons of the effects of the GC dexamethasone (Dex) showed, as hypothesized, that 20 h after addition of Dex, a time just prior to initiation of apoptosis, C1-6 and C7-14 cells shared a limited set of regulated genes (Webb et al., 2003, Medh, Webb, Miller et al., 2003). The resistant clone C1-15 shared only a few regulated genes with the sensitive clones, while it displayed GC regulation of a number of genes unto itself. None of these latter provided an obvious explanation of the resistant phenotype, nor did a comparison of basal gene expression between the sensitive and resistant clones.

Since more than 20 h of continual exposure to Dex are required to initiate apoptosis, we further hypothesized that a time-dependent network of regulated genes led to the ultimate commitment to cell death. Here, we present data on the genes regulated during Dex exposure prior to and including 20 hr. We document cumulative regulation of a number of genes that should affect the actions of the MAPK system so as to activate pro-apoptotic p38 MAPK and/or down-regulate activity of anti-apoptotic ERK and JNK. We suggest that cumulative, coordinated effects of multiple changes in gene expression, some modest in extent, coupled with post-translational influences on protein function, are responsible for the ultimate change in intracellular milieu that irreversibly signals for the machinery of apoptosis to be engaged.

2. Materials and Methods

The basic reagents, cell culture conditions and methods for RNA extraction have been described (Webb et al., 2003, Medh et al., 2003). Cells were maintained in logarithmic growth until the addition of Dex. The plasmids expressing constituently active CaN and GFP were obtained from Clontech. FK506 and CyA were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

2.1 Dex treatment and sampling

Methods for handling, growth medium and treatment of cells with steroid have been repeatedly described (e.g. (Miller et al., 2005). Briefly, cells in growth medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum were grown in a humidified 37° incubator with a 95% air/5% CO2 atmosphere. Log phase cells at 1–2×105/ml were plated in plastic tissue culture dishes. Dex to 10−6 M or an equal volume of ethanol vehicle were added and samples taken for RNA extraction 2, (or 3 in a separate experiment), 8, 12 or 20 hr later. Triplicate independent cultures were sampled.

2.2 Target labeling, hybridization and data analysis

Target labeling, hybridization to Affymetrix HG_U95Av2 and U_133 gene chips and data analysis were as described (Medh et al. 2003, Webb et al. 2003) except for the following modification: For each gene or probe set, there are 16–20 probe pairs comprised of short oligonucleotides (~25-mer). Each probe pair had a Perfect Match (PM) oligo and a Mismatch (MM) oligo acting as a hybridization control to monitor background levels. Affymetrix software uses these PM and MM values to assign a Discrimination score, which is then used in a one-sided Wilcoxon’s signed rank test versus a user-defined threshold to determine a p-value, the determining factor in calling a gene “present” or “absent”. Gene network analysis was performed using Ingenuity Pathways Analysis 3.1 (Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA). The network shown in Fig. 3 was chosen as an example because it was the “top” network, i.e. displayed the largest number of regulated genes at 20 hr.

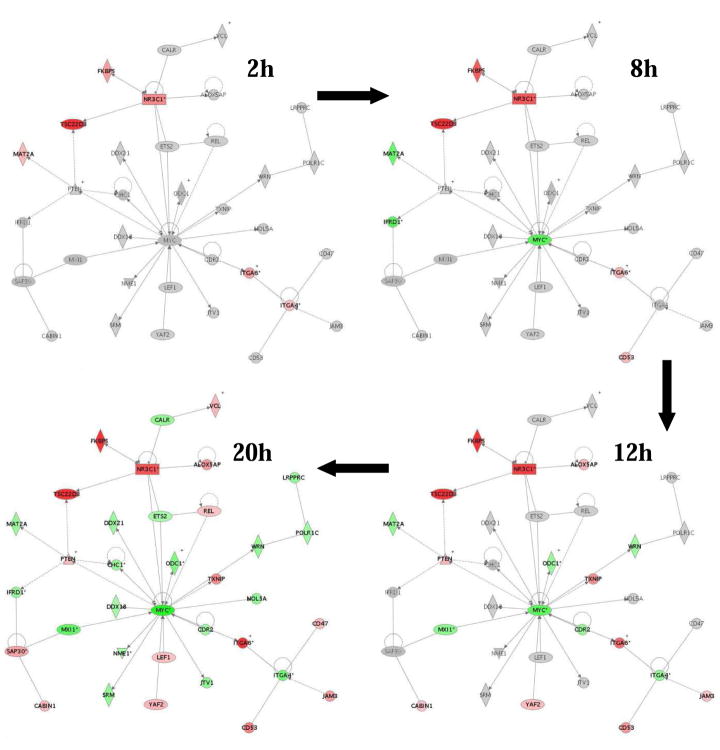

Fig 3.

Growth of GR/Myc network; pre-apoptotic interactions over time in Dex-dependent CEM clones. Red indicates increase; green, decrease

2.3 Filtering data for induced and repressed genes

Other than the determination of “absent” or “present” with the Affymetrix 5.0 software, data were analyzed using Spotfire DecisionSite, version 8.1 (Spotfire Inc., Cambridge, MA). Genes that met the first requirement of being “present” in at least 2 of the 3 experiments (5401 ± 384) were used for further data analysis. These filtered genes were then compared to their counterparts on the control or treated chips to find those that were induced or repressed at least 1.5-fold, 2-fold, and 2.5-fold. To determine if the fold changes were considered significant, the T-test/Anova function was employed in Spotfire. In some analyses, all genes whose fold change met the T-test of p<0.05 were used, as indicated. The algorithm used in this function and to determine the fold changes themselves can be found in the Spotfire DecisionSite for Functional Genomics user’s guide. For repressed genes, a 1.5-fold reduction represents a 33% drop in mRNA levels whereas a 2.0-fold reduction implies that mRNA levels were 50% less than control levels.

2.4 Statistical analysis of overall data

The entire data set for the time course experiments was evaluated for correlations in expression data and for noise. The average correlation coefficient, R over all possible pairs of experimental conditions was found to be R = 0.9428 +/− 0.0357 (1 Standard Deviation, SD). For identical experimental conditions, the triplet values for the cell line gave Rid = 0.9771 +/− 0.0052. Therefore Rid > 6 SD from the average over the entire dataset. When each cell line and time point were evaluated, the R values ranged from 0.94 to 0.97 and the SD’s from 0.16 to 0.046. Comparison of all Dex-treated and control values gave R values of 0.94 +/− 0.04 and 0.95 +/− 0.03, respectively. These results indicate that though the experiments were performed over time, the experimental data, as a whole, was quite consistent.

The noise in the data was evaluated by comparing the observed noise in the triplet values within the overall set with that generated by a random comparison of all possible triplets. The randomly generated noise as 10 times greater than that observed in the data.

These results allowed the conclusion that the data obtained show a steady control baseline over time, with low randomness, and that the steroid-treated cells do not show a general change in gene expression. The constant baseline values permitted pooling of all control data, against which the means of the triplicate time-specific samples were compared. We also compared each mean of the time-specific triplicate control samples with its Dex-treated partner mean of triplicate samples. The two methods gave similar results, with tighter SDs, as might be expected from the larger n for controls, when the pooled controls were used. The specific method for the data described herein is given in the following section.

2.5 Immunochemical Analysis

Cells were grown to a density of 2.0×105 viable cells/ml and treated with ethanol vehicle or 1 μM Dex for 24 h. After collection by centrifugation at 100 × g and a wash with 25°C PBS, the washed cell pellets were transferred to 1.5 ml centrifuge tubes and lysed on ice using 4°C M-per cell lysis buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 mM sodium fluoride, and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min 4°C in a Beckman microfuge. Supernatants were transferred to fresh cold microfuge tubes, and the protein concentration estimated using BCA (Pierce). The cell lysate (12 μg protein for JNK and 30 μg for PYK2) was mixed with 5X SDS PAGE sample buffer supplemented with 2% 2-mercaptoethanol and heated to 100°C for 5 min. Samples were electrophoresed by 8% SDS-PAGE with subsequent transfer to a PVDF membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) using a semi-dry electroblotter (Hoefer, San Francisco, CA). Membranes were washed with Tris-buffered saline (TBST) (140 mM sodium chloride, 20 mM Tris, 0.1% Tween-20, pH 7.6) and blocked for 1 h in TBST supplemented with 5% non-fat dry milk. Membranes were washed again and placed in a solution of TBST containing 5% bovine serum albumin and a primary antibody to JNK MAPK(Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), PYK2 (Cell Signaling), or actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and incubated for 16 h at 4°C with gentle agitation. Membranes were subsequently washed with TBST three times for 10 minutes each at 25°C and then incubated with a horseradish peroxidase antibody for 1 h at 25°C. After again washing as above, the membranes were saturated with ECL (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and exposed to Blue Light Autorad (ISC Bioexpress, Kaysville, UT) photographic film for various times to ensure linearity.

2.6 Calcineurin (CaN) Inhibitor experiments

After determining their optimal dosages in preliminary experiments, the CaN inhibitors FK506 and cyclosporin A (CyA) were added at final concentrations of 15 ng/ml and 1μM, respectively, to cell medium. Dex was added to a final concentration of 1 mcM. Experiments were begun at a concentration of 2×105 of log growth cells/ml. Cells were counted for total and viable cells/ml. after various times.

2.7 Electroporation

Electroporations were carried out as described (Harbour, Chambon and Thompson, 1990) with minor modifications, using CaN- or GFP-expressing plasmids. Results from triplicate samples in each experiment were averaged, and % viable cells determined for each condition by calculating: (viable transfected cells/ml + Dex) ÷ (viable transfected cells/ml).

2.8 qtPCR

Five genes which were scored as significantly induced and one that induced little or not at all were assayed by qtPCR, according to the protocols of the manufacturer, as described (Nguyen-Vu, Vedin, Liu et al., 2013).

3. Results

3.1 GC-regulated genes show increasing recruitment of genes and networks overtime

To test the hypothesis that clone C7-14, naturally sensitive to Dex-driven apoptosis and CEM clone C1-6, a sensitive revertant from resistant, would share important Dex-driven genes, changes in levels of their mRNAs were estimated after 2, 8, 12 and 20 hr of exposure to Dex. These were compared to naturally resistant clone C1-15. Using stringent limits, we had previously noted that after 20 h exposure to 10−6 M Dex, there were in the sensitive clones 39 genes whose mRNAs were upregulated ≥2.5 fold and 21 genes whose mRNAs were reduced ≥2.0-fold (Medh et al., 2003). Recognizing that lesser quantitative changes could be exceedingly important in the biological processes involved, in the present investigation we examined the new sets of regulated genes increased by 1.5, 2.0 and 2.5-fold, and those “repressed” at ≥1.5 as well as 2.0 fold. Each time point was examined in 3 independent experiments, with time-matched controls, and a p-value was determined for the resulting mean values.

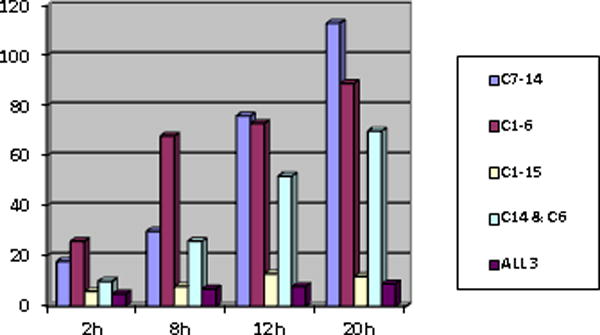

A common pool of induced or repressed genes is identified in both sensitive clones (Fig. 1, C7-14/C1-6 and Supp. Fig 1, Supp. Tabs. 1, 2). Though there are fluctuations, generally this pool increases as over time more and more genes are changed in expression as the cells remain exposed to Dex. This largely cumulative increase in regulated genes is highly suggestive of changes in expression of critical early genes leading to later altered expression of dependent genes. Fig. 1 shows the total numbers of genes whose mRNA increases over time in Dex at one arbitrary cut-off.

Fig 1.

Total genes increased ≥1.5 fold with p≤0.05 after treating cells with Dex continually for the stated times.

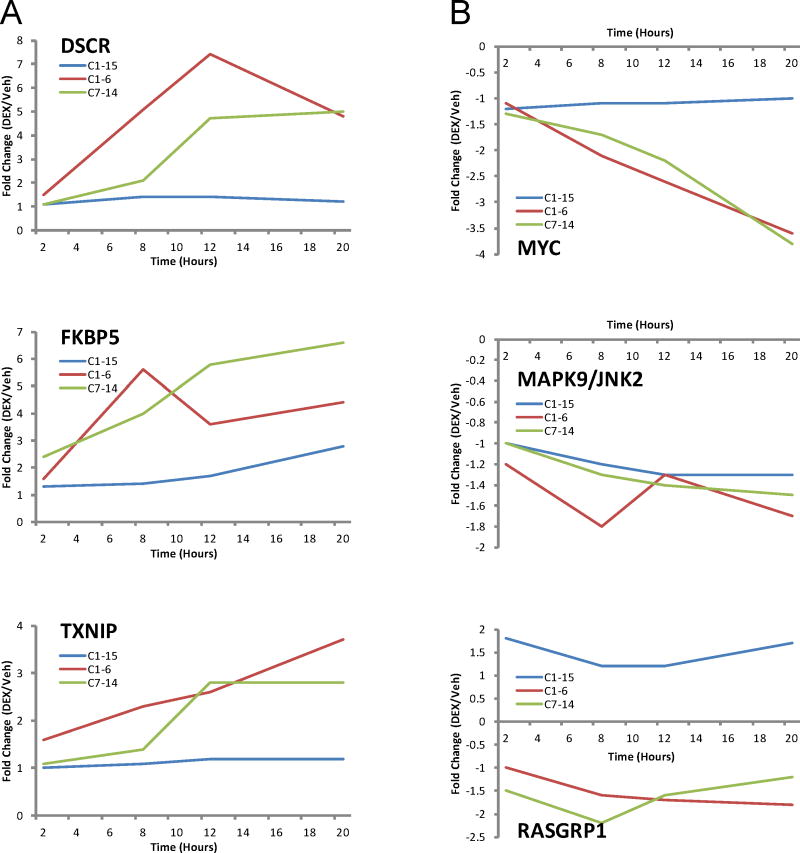

Supp. Fig. 1 displays the effect of choosing differing fold-change cut-offs and distinguishes the numbers of genes in which the average quantity of mRNA in the treated cells differed from controls by a statistically significant amount (p≤0.05). Cells of the two clones headed for eventual apoptosis (CEM C1-6 and C7-14) show more regulated genes than the resistant cells (C1-15), but C1-15 cells have genes under steroidal regulation. Some of these are also regulated in the sensitive clones (Fig. 1, ALL 3). Fig. 2 shows the time course of arbitrarily selected induced or repressed genes, demonstrating the general trends towards increase or decrease as well as the fluctuations in individual genes that may occur over time.

Fig 2.

Time course of regulation up (A) or down (B) of selected genes.

After 2 h in Dex, sensitive cells showed no reduced genes, but reported increased mRNAs of a few genes. Among these, the GR (NR3C1), FKBP5, ITGA6 and GILZ/TSC22D3/DSIPI genes are most strongly induced. The 2 hr exposure was chosen to sample because during that interval the effect of Dex is more likely to be due purely a cis action of the activated GR on the gene in question than at the later times. Later, most of these changes increase, and many additional genes in the network become altered in expression. The persistence and increases in these changes adds to the likelihood that, though some are modest in quantity, they are authentic. Since the number of genes seen to be regulated after 2 hr of Dex was small, at a later date and employing gene chips that report on about 39,000 transcripts as opposed to the 10,000 transcripts reported on by the time-course chips, we repeated the Dex exposure for 3 hr on C7-14 and C1-15 cells, since gene expression changes after three hr still should be mostly “direct” GR actions. Generally, the data confirmed and extended the results from the 2 hr experiment. In C7-14 cells, at p values of ≤ 0.05, the 3 hr chips showed the mRNAs of 2,800 genes to be altered (136 of these with a fold change over 2). In C1-15 cells, 3,378 were altered with statistical significance (486 over 2-fold). Up and down changes over 2-fold occurred for 38 RNAs in both clones combined.

3.2 Validations of chip data

Six genes, scored as induced or not by chip assay, were independently assayed by qtPCR. In the original experiment, BTG1, GR, RCAN1, FKBP5, AND DUSP10 were all found to be increased at one time or another. The 3-hour chip experiment again showed their induction in both sensitive and resistant cells. GAPDH showed no increase in the time course data but did have a small, statistically significant increase in C1-15 cells in the 3 hr experiment. Cells from the 3 hr expt were assayed; the PCR results confirm that Dex treatment increased the genes’ RNAs but for GAPDH in C7-14 cells. We note that in each case, the basal level of C7-14 cell mRNA was 2 or more times that of the mRNA from C1-15 cells. This may have relevance to the suggested use of the induction of certain genes as a marker for GC sensitivity.

Several additional results indirectly support the validity of the chip data. First, earlier publications had shown that MYC is transcriptionally down-regulated by Dex in sensitive cells. Secondly, in these time course data we found JNK RNA down and p38 activity (not RNA) up, consistent with our other experiments on these MAPKs. Finally, our original report of a late, Dex-dependent increase in the mRNA of the pro-apoptotic gene Bim (Medh et al., 2003) was confirmed in the present experiments. That late Bim induction is important for setting off the eventual apoptotic pathway has been confirmed and expanded on in other reports (Zhang and Insel, 2004, Kfir-Erenfeld, Sionov, Spokoini et al., 2010, Lu, Quearry and Harada, 2006)

3.3 Gene networks identified by analysis of regulated genes

We searched for the possible gene networks that incorporated our regulated genes by use of the Ingenuity IPA program. Beginning with data from the most stringent criteria and progressing to the least, we found that the same networks were identified in increasing detail. Here we focus on two of these.

3.3.1 Repression of gene expression and the c-myc/MYC-dependent network

The network analysis confirms published data indicating that c-myc is an important node. Fig 3 depicts the growth of interconnections between the GR and MYC over time in the best-scoring network generated using results from 280 gene probes (including duplicates) identified as having changed ≥1.5 fold at 20 hr (146 increased, 134 reduced) in both sensitive clones.

Though it was not picked up so early on the chips here used, down-regulation of c-myc begins as early as 1–2 h after addition of Dex (Yuh and Thompson, 1989; Zhou, Medh and Thompson, 2000), consistent with subsequent down-regulation of genes dependent on it as a transcription factor. By inspection of Myc websites {(Zeller, Jegga, Aronow et al., 2003), www.myc-cancer-gene.org/site/mycTargetDB.asp} 60 (44%) of the 134 repressed gene probes, were identified as regulated by or associated with Myc. The reported effects of Myc on these genes are mostly transcriptional up-regulation and/or direct protein:protein interactions. In most cases, the maximum reductions in the Myc-dependent transcripts were reached only after 20 h Dex treatment. Supp Table 1 shows all Dex down-regulated genes: Part A, Myc-dependent genes; Part B, the remaining down-regulated genes. Together, our published and this data suggest that profound depression of c-myc expression in both sensitive clones is followed by decreased expression of a large number of Myc-dependent genes. A number of these are relevant to the MAPK network (Tab. 2)

Table 2.

Dex-repressed genes related to MAPK pathways

| Probe ID | Gene Symbol | C7-14 | C1-6 | C1-15 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 hr | 8 hr | 12 hr | 20 hr | 2 hr | 8 hr | 12 hr | 20 hr | 2 hr | 8 hr | 12 hr | 20 hr | ||

| MYC-dependent | |||||||||||||

| 37668_at | C1QBP | −1.1 | −1.1 | −1.2 | −1.8* | −1.0 | −1.3 | −1.1 | −2.0 | 1.0 | −1.1 | −1.0 | 1.0 |

| 1519_at | ETS2 | −1.0 | −1.4 | −1.4 | −1.6 | −1.5* | −1.6 | −1.7 | −1.7* | 1.1 | −1.2 | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| 40012_at | LRP8 | 1.1 | −1.7* | −1.6 | −2.2* | −1.2 | −1.3 | 1.0 | −2.8* | −1.1 | −1.1 | −1.2 | −1.2 |

| 38431_at | MAPK9 | −1.0 | −1.3 | −1.4 | −1.5* | −1.2 | −1.8* | −1.3 | −1.7* | −1.0 | −1.2 | −1.3 | −1.3 |

| 654_at | MXI1 | −1.2 | −1.3 | −1.8* | −2.7* | −1.1 | −1.6* | −1.3 | −1.6 | −1.1 | −1.2 | 1.1 | −1.0 |

| 1985_s_at | NME1 | −1.0 | −1.0 | −1.2 | −1.5* | −1.2 | −1.2 | 1.0 | −1.7 | 1.1 | −1.0 | 1.0 | −1.1 |

| MYC-independent | |||||||||||||

| 39932_at | DUSP7 | −1.3 | −1.4 | −1.8* | −2.0 | −1.2 | −1.4 | −1.0 | −2.0* | −1.1 | −1.2 | −1.3 | 1.0 |

| 1267_at | PRKCH | 1.3 | −1.7 | −1.2 | −1.6 | −1.6* | −1.7* | −1.3 | 1.1 | 1.0 | −1.3 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| 39780_at | PPP3CB | 1.1 | −1.6 | −1.0 | −1.1 | 1.2 | −1.6 | 1.1 | −1.0 | −1.3 | 1.1 | −1.2 | 1.1 |

| 33291_at | RASGRP1 | −1.5 | −2.2* | −1.6 | −1.2 | −1.0 | −1.6 | −1.7 | −1.8 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.7 |

Averages of genes repressed ≥1. 5X in at least one time point in both glucocorticoid-sensitive cell lines C7-14 and C1-6. Instances at which p-value <0.05 for three treated replicates as compared to their respective time-matched controls are indicated by *.

3.3.2 Time course of genes induced by Dex

Increasing numbers of genes exclusive to the two sensitive clones are induced as time increases (Fig. 1, Supp. Fig. 1, Supp. Table 2). By 20 h the cells are poised just at the onset of irreversible apoptotic events, and over the subsequent 48–72 h, increasing numbers of cells are irreversibly recruited to apoptosis. At ≥ 1.5-fold, the mRNAs of 83 genes were increased to a statistically significant extent, and of these 43 changed ≥2.0 fold. Of the 83, duplicate probes happened to be included on the chips for 12, strengthening the likelihood that their changes in expression are authentic. As with the repressed genes, the number of genes and the pathway linkages revealed by the genes induced in the sensitive clones are striking with many mRNA increases consistent with enhancement of the action of proapoptotic p38 or with reduction of antiapoptotic ERK & JNK actions.

3.3.3 Many Dex-regulated genes affect the MAPK system

Several down-regulated genes besides MYC impact the MAPK pathway (Table 2). Noteworthy among these are Myc-dependent MAPK9/JNK2 (the predominant JNK form in CEM cells) and calreticulin, which is involved in nuclear export of the glucocorticoid receptor (Holaska, Black, Love et al., 2001) and in regulation of Ca++ stores in the endoplasmic reticulum lumen (Gelebart, Opas and Michalak, 2005), and hence, of calcineurin (CaN) function. CaN has several connections to MAPKs such that reduction of its level or inhibition of its activity would tend to increase p38 activity and/or diminish ERK/JNK activity, e.g. by increasing VCL (Fig. 3, 20 hr and 3.3.4.1). Other genes in the down regulated group are involved in controlling the activity levels of specific MAPKs or encode proteins phosphorylated by MAPKs.

3.3.4 Glucocorticoid/MAPK pathway interactions of induced genes

Examination of the time-course of induced genes for those involved in the MAPK system revealed that many have been reported to directly or indirectly enhance p38 MAPK action and/or depress the action of ERK and JNK. Table 3 lists these 13 genes with their fold-changes overtime.

Table 3.

Dex-induced genes related to MAPK pathways

| Probe ID | Gene Symbol | C7-14 | C1-6 | C1-15 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 hr | 8 hr | 12 hr | 20 hr | 2 hr | 8 hr | 12 hr | 20 hr | 2 hr | 8 hr | 12 hr | 20 hr | ||

| 735_s_at | AKAP13 | −1.0 | 1.2 | 2.5* | 3.4* | 1.3 | 2.6* | 2.6* | 3.5* | −1.1 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.4 |

| 1717_s_at | BIRC3 | −1.0 | 1.7* | 4.1* | 2.8* | 1.4 | 4.0* | 2.9 | 5.8* | 1.4 | −1.1 | −1.0 | −1.1 |

| 37652_at | CABIN1 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.7* | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 2.0* | −1.0 | 1.2 | −1.1 | 1.0 |

| 35311_at | CREG1 | 1.1 | −1.0 | 1.2 | 1.6* | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 2.0 | −1.1 | 1.1 | −1.0 | 1.0 |

| 32168_s_at | DSCR1 | 1.1 | 2.1* | 4.7* | 5.0* | 1.5 | 5.1* | 7.4* | 4.8* | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

| 36629_at | DSIPI | 12.9* | 28.0* | 21.2* | 33.1* | 10.1* | 42.3* | 46.4* | 20.4* | 18.6* | 17.6* | 17.3* | 5.0* |

| 38555_at | DUSP10 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 2.0* | 2.7* | 1.5* | 1.3 | 1.9* | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| 34721_at | FKBP5 | 2.4* | 4.0* | 5.8* | 6.6* | 1.6* | 5.6* | 3.6* | 4.4* | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.7* | 2.8* |

| 41431_at | ICK | −1.1 | −1.4 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.1 | −1.1 | 1.6 | −1.9 | 1.0 | −1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| 33804_at | PTK2B | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 2.1* | −1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 4.2* | 1.2 | −1.3 | −1.2 | 1.1 |

| 40631_at | TOB1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.6* | 1.2 | 1.6* | 1.6* | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| 31508_at | TXNIP | 1.1 | 1.4 | 2.8* | 2.8* | 1.6* | 2.3* | 2.6* | 3.7* | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| 36601_at | VCL | −1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.5* | 1.3 | 1.9* | −1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

Averages of genes induced ≥1. 5X in at least one time point in both glucocorticoid-sensitive cell lines C7-14 and C1-6. Instances at which p-value <0.05 for three treated replicates as compared to their respective time-matched controls and fold change must be ≥1.5 are indicated by *. Note that DSIPI and FKBP5 are induced in resistant C1-15 cells as well as in sensitive clones.

3.3.4.1 Effects on ERK

Induced genes that directly or indirectly inhibit ERK include Vinculin (VCL), cellular repressor of E1A-stimulated genes (CREG), glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ/DSIPI), and several regulators of Calcineurin (CaN).

Dex increases the structural protein VCL transcripts by 1.5–1.9-fold in both sensitive clones by 8-12 h and beyond. Basal expression of VCL in the resistant C1-15 clone is similar to that in the sensitive clones, but these VCL levels do not change after addition of Dex. VCL binds actin and paxillin, the latter a scaffold protein to which an array of signalling and structural proteins bind at the plasma membrane. Among the paxillin-bound proteins is focal adhesion kinase (FAK), and paxillin: FAK enhances activation of ERK1/2. By competing for paxillin, VCL diminishes this mechanism of activating ERK (Subauste, Pertz, Adamson et al., 2004).

CREG also diminishes ERK activity, without affecting JNK or p38 MAPK activities (Xu, Liu and Chen, 2004). By 20 h CREG is induced an average of 1.6-fold and 2.0-fold in C7-14 and C1-6 cells, respectively. It shows no regulation in C1-15 cells. Considerable attention has been given to the possibility that GILZ/TSC22D3/DSIPI is involved in lymphoid cell apoptosis induced by glucocorticoids (Riccardi, Cifone and Migliorati, 1999, Riccardi, Zollo, Nocentini et al., 2000, Delfino, Agostini, Spinicelli et al., 2004, Ayroldi, Zollo, Macchiarulo et al., 2002). GILZ inhibits AP-1 activation, binds and inhibits NFκB, and binds Raf-1 to prevent activation of downstream MEK and ERK. GILZ is strongly induced (10–46 fold) in both sensitive clones, at 2 h and later. However, GILZ also is strongly induced (5–19 fold) also in C1-15, the clone resistant to Dex-dependent apoptosis. Thus, GILZ induction alone is not sufficient to cause apoptosis of these lymphoid cells; however basal GILZ mRNA levels are lower in C1-15 cells. The cellular quantity of GILZ therefore may be important (see 4. Discussion) Several induced genes are known to reduce Calcineurin (CaN) activity. CaN, a Ca++-sensitive protein phosphatase active as a heterodimer of transcripts from two genes (catalytic subunit PPP3CA or B and regulatory subunit PPP3R1), is central in pathways that affect activation of several ERK isoforms (Sanna, Bueno, Dai et al., 2005, Molkentin, 2004), and notably, in thymocytes, removal of CaN activity reduces ERK activation (Neilson, Winslow, Hur et al., 2004). Thus it might be expected that Dex would produce gene expression changes which reduce CaN levels or activity. Two genes inhibitory to CaN are induced by Dex in both apoptosis-sensitive clones but not in the resistant clone. These are CABIN1 (Esau, Boes, Youn et al., 2001) and Calcipressin 1/RCAN1/DSCR1/Adapt78/RCN1 (Harris, Ermak and Davies 2005, Cook, Hejna, Magnuson et al. 2005, Chan, Greenan, McKeon et al. 2005, Nagao, Iwai and Miyashita 2012, Saenz, Hovanessian, Gisis et al., 2015). Calcipressin 1/DSCR1 is strongly induced in both Dex-sensitive clones but only weakly, if at all, in CEM C1-15 cells (Table 3). The third induced gene is the FK506 binding protein FKBP5, though this gene is strongly induced in the resistant clone as well. In addition to its well-studied chaperone interactions with the GR (Pratt, Galigniana, Morishima et al., 2004), FKBP5 has been shown to be induced in thymocytes by Dex and to bind and inhibit CaN (Baughman, Wiederrecht, Campbell et al., 1995, Baughman, Wiederrecht, Chang et al., 1997, Li, Baksh, Cristillo et al., 2002), possibly by a mechanism independent of its FKBP12 domain. Finally, as noted, calreticulin/CALR is down-regulated, which by its effects on Ca++ release from the ER, would be expected to reduce CaN activity.

Reduced CaN activity may also contribute to the growth arrest/apoptosis of sensitive CEM clones by pathways other than ERK inhibition

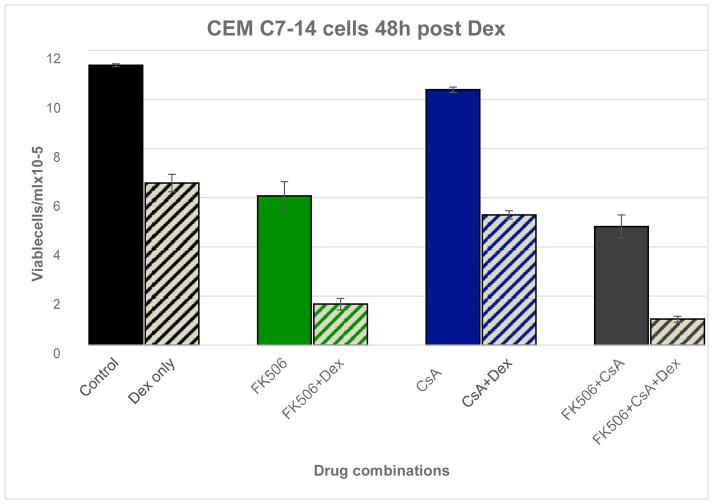

In addition to its effect on ERK, in concert with MEF2, CaN is a major inducer of nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT). NFATs are important factors in the induction of pro-growth, antiapoptotic cytokines. Inhibiting CaN might thus be expected to reduce NFAT function and consequently cytokine production. In thymocytes, Dex has been observed to interfere with NFAT:AP-1 interactions (Wisniewska, Pyrzynska and Kaminska, 2004). NFATC3 mRNA is expressed in our Dex sensitive CEM clones and after Dex treatment is reduced by 30–80% in both sensitive clones (reaching statistical significance at several time points). Lastly, as noted above, CaN catalytic subunit beta transcript (PPP3CB) levels themselves may be reduced at times (1.6-fold) exclusively in the sensitive clones (probe ID 39780_at, Table 2, Supp. Tab. 1B). Thus, by several means, changes in gene expression in the sensitive clones are consistent with reductions in anti-apoptotic effects of CaN. We performed preliminary tests to estimate the extent to which CaN may contribute to Dex-induced apoptosis in CEM cells by use of CaN inhibitors FK506 and cyclosporine A (CsA). As expected, the inhibitors were somewhat toxic; however, they enhanced Dex-induced apoptosis of C7-14 cells (Fig. 4). In C1-15 cells, the inhibitors alone produced considerable cell kill, and in combination with Dex further significantly increased total apoptosis (Supp. Fig. 2).

Fig 4.

CaN inhibitors enhance CEM cell kill by Dex.. C7-14 cells were exposed to Dex, FK506, CsA, or combinations of the three for 48 hr. This figure shows the effects after 48 hr, when they were most striking. Between each pair of bars, p was ≤ 0.008. Further data in Supp Fig 2 and Table 3.

In both cell lines, comparisons of the extent of kill by each agent alone with that by the combined agents suggest that the inhibitors worked synergistically with Dex. Full dose-response curves would be necessary to establish this tentative conclusion as correct.

Since neither inhibitory compound acts only by inhibiting CaN, we carried out preliminary tests of CaN’s contribution to Dex-dependent apoptosis by electroporating cells with an expression plasmid for CaN. The cells with added CaN showed reduced sensitivity to Dex (Supp. Tab. 3)Downstream from ERK: Suppression of ERK activity would reduce its effect on genes that control growth. One of these ERK substrates is TOB1, a lymphoid cell quiescence and sometimes pro-apoptotic gene whose activity is blocked by ERK-catalyzed phosphorylation (Maekawa, Nishida and Tanoue, 2002). TOB1 is induced to a statistically significant extent in both sensitive clones, not in the resistant clone. Thus, Dex-dependent inhibition of ERK activity would enhance the activity of TOB1, and coupled with the increase in TOB1 mRNA levels, may play a role in the well-documented inhibition of the cell growth cycle brought on by Dex (Harmon, Norman, Fowlkes et al., 1979) as well as Dex-dependent apoptosis.

In short, through a variety of interacting mechanisms, several genes that each are moderately induced exclusively in the Dex-sensitive clones, may work collectively to lower the activity of major ERK isoforms. The net effect would be to reduce the function of this “pro-life, anti-apoptotic” group of MAPKs.

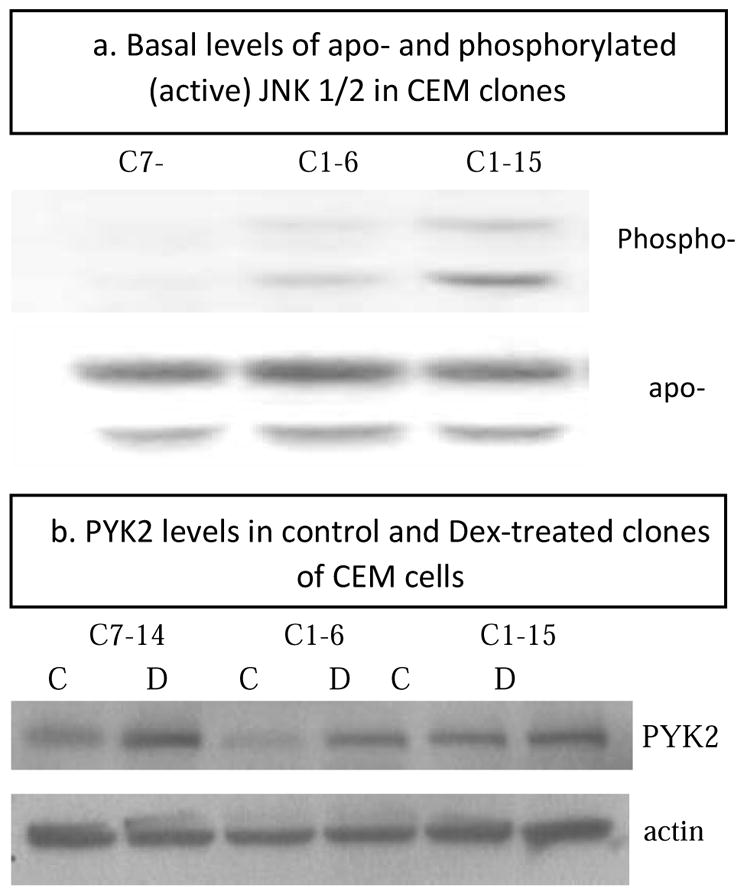

3.3.4.2 Regulation of anti-apoptotic JNK/MAPK9

Dex treatment consistently reduces JNK (MAPK9) transcript levels in both sensitive CEM clones by 25–50% at 8 h and after (Supp Table 1A, line 4). In addition, we find that basal levels of phospho JNK, the active form, are undetectable (C7-14) or extremely low (C1-6) in these clones, whereas this phosphoprotein that counters the apoptotic effect of Dex, is significantly higher in the Dex-resistant C1-15 cells (Fig. 5a.) Thus in the sensitive cells, activated/phosphorylated JNK/MAPK9 is lower to begin with, and in Dex, JNK/MAPK9 transcripts are reduced.

Fig 5.

Immunoblots from extracts of 3 clones of CEM cells showing a) basal levels of JNK1/2 protein, total (apo-) and phosphorylated/activated (Phospho-) and b) PYK2 protein levels at control/basal state (C) and after Dex treatment (D).

Several induced genes regulate JNK: ASK1/MAP3K5 activates the MAPKKs upstream of both JNK and p38 (Matsukawa, Matsuzawa, Takeda et al., 2004). Several regulators of ASK1 activity show relevant steroid-dependent effects. ASK1 activity is inhibited when it is bound to thioredoxin (TRX), glutaredoxin (GRX), or protein 14-3-3. In our sensitive clones, two genes are induced that act to remove these inhibitory proteins from ASK: TXNIP/VDUP1 binds TRX, and AIP/BIRC3 binds protein 14-3-3; in each case, the result is to free ASK1 from its inhibitor (Zhang, He, Liu et al., 2003). TXNIP is induced by 2–8 h, eventually increasing about 3-fold, and AIP is induced in both sensitive clones by 8 h and eventually increases 4–5-fold. We also document induction of the ASK1 binder-inhibitor GRX, a redox-sensing protein shown to block ASK1 in breast cancer cells (Song, Rhee, Suntharalingam et al., 2002) under conditions of glucose deprivation. Whether this circumstance is applicable to CEM cells in our glucose-plentiful medium is not clear. In principle, ASK1 activation promotes phosphorylation/activation of both p38 and JNK; however, our data show that in sensitive CEM cells, Dex leads to activation of p38, but not JNK. This differential effect may be explained in part by the observed induction of the phosphatase DUSP10/MKP5, which dephosphorylates/inactivates JNK. Early work suggested that DUSP10 is capable under some circumstances of dephosphorylating both JNK and p38, with little effect on ERK (Theodosiou, Smith, Gillieron et al., 1999, Zhou, Wang, Zhao et al., 2002), but development of MKP5 null mice has revealed that in T cells in vivo, the primary target of this phosphatase is JNK (Zhang, Blattman, Kennedy et al., 2004). Thus, the induction of DUSP10/MKP5 in sensitive the T-lineage CEM cells is consistent with the observed diminished JNK relative to p38 activity. In sum, several genes are altered in expression consistent with the outcome of lowering the activity of the antiapoptotic actions of ERK and JNK.

3.3.4.3 BRX, ICK/MRK and PYK2 are Dex-induced genes that activate p38

Several genes whose mRNA increases during exposure to Dex in sensitive CEM cells phosphorylate/activate pro-apoptotic p38 MAPK. The gene for A-kinase anchoring protein BRX/AKAP-Lbc/AKAP13//Ht31 (Rat homolog, RT 31) is induced 3.5-fold in both sensitive clones, but not in resistant clone C1-15. Immunochemical protein blots show that the shorter BRX protein, derived from AKAP-Lbc mRNA by alternate splicing and encoded by the C-terminal part of the gene, is the form found in our clones. BRX activates GRα (Kino, Souvatzoglou, Charmandari et al., 2006) and estrogen receptors α and β. This action specifically requires p38 MAPK (Driggers, Segars and Rubino, 2001). We have shown that phosphorylation of Ser 211 in hGR, important for increasing GRs transcriptional and apoptotic activity, is carried out by p38 MAPK (Miller et al., 2005). We suggest that the GC-driven increase in BRX enhances p38 phosphorylation of GR, thus enhancing its activity.

Related adhesion focal tyrosine kinase (RAFTK/PYK2/PTK2B/FAK2) is induced 2-4 fold by Dex in the sensitive clones CEMs 1-6 and 7-14, whereas it is not altered in resistant clone CEM 1-15 (Table 2). Basal mRNA levels of expression in the 3 clones are roughly equivalent. We confirmed that this induction of mRNA corresponds to increases at the protein level (Fig 5b). In cardiovascular and neural cells RAFTK/PYK2 differentially activates p38 MAPK, and this can lead to apoptosis (Melendez, Turner, Avraham et al., 2004), neurite outgrowth (Huang, Borchers, Schaller et al., 2004), and endothelial cell migration (McMullen, Keller, Sussman et al., 2004). PYK/RAFTK is different from, though related to, focal adhesion kinase (FAK). Unlike FAK, RAFTK is not localized to focal adhesions, is activated by Ca++ and Src, and is inhibited by binding to paxillin. (The observed increase in VCL, Table 2 would be expected to release this inhibition). Other signals are known to lead to activation of RAFTK in various cell systems (Medh et al., 2003, Avdi, Nick, Whitlock et al., 2001, Park, Park, Bae et al., 2000, Aiyar, Park, Aldo et al., 2010). Of closest relevance to our CEM system is the report that in Jurkat cells PYK2/RAFTK mediates activation of JNK and p38 following T-cell receptor stimulation (Katagiri, Takahashi, Sasaki et al., 2000). These and other reports show that activation of RAFTK leads to activation of p38 MAPK (and sometimes JNK as well, but not ERK).

ICK/MRK/MTLK (intestinal cell kinase/MLK-related kinase) is a human MAP3K with homology to the mixed lineage kinase (MLK) family. The preponderance of evidence indicates that ICK preferentially activates p38 MAPK and JNK, not ERK (Tosti, Waldbaum, Warshaw et al., 2004). Studies of p38 isoforms have shown that each may have special actions, and these can be pro- or anti-apoptotic, depending on the circumstances (Pramanik, Qi, Borowicz et al., 2003, Wang, Huang, Sah et al., 1998). Our clones all strongly express pro-apoptosis p38α mRNA and the RNAs for the other isoforms to varying lesser extents. Detailed proteomic analysis will be required to evaluate fully the effect of ICK induction on each isoform. Release of inhibition of p38 may come in part from the observed reduction in CaN via its regulation of MKP-1/DUSP1, which dephosphorylates and thus inactivates p38. Reduced CaN levels, as well as reduced CaN activity (see above) would act to reduce MKP-1 activation, and reduced MKP-1 activity would support maintenance of active p38, consistent with our data showing that Dex treatment increases p38 activity.

In sum, the genes for BRX, PYK2 and ICK are altered in such a way as to enhance p38 MAPK activation, and we have shown that p38 activity plays an important role in Dex-dependent apoptosis in this lymphoid leukemic cell system. This conclusion has been confirmed and extended by data showing that active p38 is critical for the induction of BIM, the BCL-2 family member critical for the ultimate propulsion of CEM cells into apoptosis (Lu et al., 2006).

3.5.1.5 Some regulated genes downstream of Myc may affect p38

Among the large number of genes known to be downstream of c-myc are a set reported to be regulators of p38 (Tab 2).

Use of Transcriptomine reveals crosstalk between GC and NOTCH pathways in CEM cell clones

The data mining program Transcriptomine (Ochsner, Watkins, McOwiti et al. 2012; Becnel, Ochsner, Darlington et al. 2017) is devoted to nuclear receptor pathway effects. When we queried this source for human immune system GC effects, one instructive data set was found: CUTLL1 cells. These GR-positive, t(7;9) T-lymphoblast leukemia cells are Dex-resistant but can be switched to Dex-sensitive by blocking the gamma-secretase system necessary to cleave Notch and start its signaling cascade (Real, Tosello, Palomero, et al. 2009; Real and Ferrando 2009). Though Dex alone can affect expression of many CUTLL1 cell genes, many of these are more strongly affected by a gamma-secretase blocker (Compound E) plus Dex, and many more are induced or repressed only by the combined drugs. We compared lists of genes we found to be induced or repressed exclusively in Dex-sensitive CEM C1-6 and C7-14 cells at 12 and 20 hr (Tabs 1 & 2, Webb, Miller, Johnson, et al. 2003) with those in CUTLL1 cells shown to be regulated after 24 hr of Dex or Compound E +Dex. A number were in the group regulated only by E+Dex (Supp. Material Tab 4) consistant with the hypothesis that Notch-GC pathway crosstalk exists in the CEM system as well. Furthermore, examination of basal levels of Notch expression showed it to be 5-fold higher in the resistant clone C1-15 (Tab. 3 in Webb, Miller, Johnson, et al. 2003). We then scanned our 3 hr data set for genes relevant to NOTCH pathway control and found several regulated to a statistically significant extent only in the two Dex-sensitive CEM clones (Supp. Material Tab 5). While not exhaustive, these data-mining results encourage further exploration of NOTCH-GC pathway crosstalk in Dex-resistant lymphoblastic leukemias, including those without a t(7;9) rearrangement.

Table 1. PCR validation of gene chip data.

Columns 2–20 hr: gene chip fold change results for 5 genes showing increased mRNA after Dex for at least one time point for both CEM C7-14 AND C1-15 cells, and for one gene (GAPDH) not induced in 2–20 hr gene chip experiments, though induced slightly with statistical significance in C1-15 cells in 3 hr experiment. Column “qtPCR FC:” fold change by qtPCR in cells sampled from single time 3 hr experiment. Note: in PCR assay, basal levels of C7-14 mRNAs were ≥ 2X higher than C1-15. a. single time point, 3 hr experiment. b. p ≤ 0.05

| GENE | CELL | GENE CHIP FOLD CHANGE | qtPCR FC: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 2 HR | 3 HR | 8 HR | 12 HR | 20 HR | 3 HRa | ||

| DUSP10 | C7-14 | 1.6 | 1.3b | 1.2 | 2.0b | 2.7b | 2.8 |

| C1-15 | 1.4 | 1.5b | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 7.0 | |

| RCAN1 | C7-14 | 1.1 | 1.7b | 2.1b | 4.7b | 5.0b | 1.75 |

| C1-15 | 1.1 | 1.3b | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 2.9 | |

| NR3C1 (=GR) | C7-14 | 2.3b | 2.8b | 3.6b | 3.9b | 3.7b | 2.8 |

| C1-15 | 1.15 | 1.3b | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.3 | |

| FKBP5 | C7-14 | 2.4b | 2.7b | 4.0b | 5.8b | 6.6b | 2.7 |

| C1-15 | 1.3 | 1.4b | 1.4 | 1.7b | 2.8b | 6.3 | |

| BTG1 | C7-14 | 3.4b | 5.5b | 5.0b | 7.0b | 9.3b | 3.8 |

| C1-15 | 1.5b | 1.9b | 1.9b | 1.6 | 1.9 | 9.4 | |

| GAPDH | C7-14 | 1.06 | 1.0 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 1.03 | 0 |

| C1-15 | 1.05 | 1.13b | 1.05 | 1.11 | 0.9 | 2.6 | |

Results from 3 hr experiment

p < 0.05 (usually ≪ 0.05)

4. Discussion

We tested the hypothesis that Dex-regulated gene networks relevant to the eventual apoptosis of leukemic CEM cell clones would be revealed by following the time-course of altered mRNA levels during the 20 hr window of Dex treatment which, in these cells, precedes the onset of apoptosis. These regulated networks were predicted to be distinctive to two CEM clones sensitive to Dex-induced apoptosis and to differ from genes affected by Dex in a resistant clone. Our data support with this hypothesis. Two experiments were performed-each in triplicate. In experiment 1, cells were exposed to 10−6 M Dex and sampled after 2, 8, 12 and 20 hr. In follow-up experiment 2, Dex-treated C7-14 and C1-15 cells were sampled after 3 hr.

4.1 General observations

Our original analysis (Medh et al., 2003) using this system had ruled out the possibility that C1-15 cells lacked all response to GCs, though resistant to apoptosis. However, the gene responses in C1-15 cells are markedly different from the sensitive clones. Follow-up data confirm this result and further show a cumulative pattern of differential gene expression in the sensitive versus the resistant clones. While this manuscript was in preparation, an independent report on these cells also confirmed the differential responses over time and noted the fluctuations in expression from individual genes (Chen et al., 2013).

An important side note is the fact that GILZ/TSC22D3 and FKBP5 both show robust fold induction in the resistant clone. Since their induction has been proposed as a standard for GC sensitivity, our data indicate that simple use of their Fold-change data could lead to incorrect designations of sensitivity, i.e. “false positives,” with important clinical consequences. We note, however, that the basal levels of the two genes were lower in the resistant cells (Fig 2, Tab 1); so the final amounts of their proteins could be relevant, as could the effects of other genes networked with the two “indicator” genes.

The fact that sensitive clone C1-6 is a sister to clone C1-15, obtained during the same cloning, is important, since it suggests that the relatively few GC-responsive genes that C1-6 shares with sensitive clone C7-14 are likely to be especially relevant to the apoptotic outcome.

Since relatively few genes showed a response in both C7-14 and C1-6 cells after 2 hr of Dex treatment, an interval during which direct GC:GR cis-regulation of genes is likely, we conclude that many later effects depend on gene network relationships stemming from the earlier changes.

GCs affect most cells, and most cells contain GR; so it is reasonable that many regulatory pathways have been shown to interact with the GR path (see 1. Intro). Since we have documented the importance of the MAPK networks for GC-driven apoptosis, we focused on these interactions in this analysis.

4.2 JNK and ERK

These antiapoptotic genes are regulated directly and indirectly to reduce their effect in sensitive GC-treated cells. Basal phosphorylated/activated JNK is higher in C1-15 than in C1-6 or C7-14 cells. GCs induce a DUSP that dephosphorylates/inactivates JNK, and GC treatment may also reduce JNK mRNA. MYC, down-regulated by Dex, is important for JNK transactivation, and the downregulation of MYC may contribute to or even be entirely responsible for the down-regulation of JNK RNA. Decreases in a number of other MYC-dependent genes with connections to the MAPKs were observed. Several genes that can directly inhibit or reduce ERK activity are induced by GCs, and several others are induced that can block the activating effect of CaN on JNK.

4.3 Proapoptotic p38 MAPK

In the sensitive clones GC treatment raises the transcript level of several genes whose actions are known to promote p38 activity and effects. As with the other MAPKs, these effects may be direct or indirect, through other gene products.

Further, manipulation of MAPK levels controls the apoptotic sensitivity of other malignant lymphoid cell lines as well as CEM cells (Garza et al., 2009). Epigenetic manipulation to restore Dex sensitivity of resistant CEM cells alters the levels of ERK/JNK/p38 as would be predicted (Miller, Geng, Golovko et al., 2014). The analysis presented here supports the view that concerted, relatively small effects of many genes and their protein products bring on the circumstances that demands induction and “permits” of the genes ultimately responsible for apoptosis in these GC-treated leukemic cells. This would be analogous to the powerful “background effect,” well documented in inbred mice. We propose that the cumulative result is similar to the many tiny threads with which the Lilliputians restrained the giant Gulliver (Swift, 1726). Clearly, these results offer opportunities for detailed exploration of the important regulatory connections involving the MAPKs and the apoptotic effects of GCs on many malignant lymphoid cell types.

5. Conclusions

The data presented support the hypothesis that over time, a complex interactome induced by Dex in sensitive CEM leukemic cells leads to apoptosis. Two clones of sensitive cells show induction/repression of many genes, a small pool of which is seen to be regulated in both sensitive clones.

Many regulated genes are capable of affecting the MAPK system to reduce the efficacy of anti-apoptotic JNK and ERK or to enhance the activity of pro-apototic p38 MAPK. These effects are diagrammed in Fig. 6.

-

CEM cells insensitive to Dex-induced apoptosis nonetheless do contain Dex-sensitive genes. Most of these are different from or are induced to much lower levels than in sensitive cells.

The induction of two genes (GILZ/TSC22D3, FKBP5) has been widely cited as infallible markers for sensitivity to GC-driven cell death. Both were induced by Dex in our resistant clone, and one by Dex alone in resistant CUTLL1 cells. This means that neither GILZ nor FKBP induction per se is both necessary and sufficient for GC-driven apoptosis. Their use as diagnostic predictors could lead to false positives.

The build-up of regulated genes suggests that primary inductive or repressive effects of Dex on a relatively small number of genes leads to ramifying effects on other genes. These then lead to the eventual triggering of irreversible apoptotic events, e.g. Bim induction.

There is crosstalk between the NOTCH and GC pathways in these CEM clones.

Fig 6.

Interactions of GR, MYC and MAPK pathways, from analysis of time course of altered gene regulation in CEM cells. GC (triangle) enters cell and activates GR, which by up- or down-regulating many genes, causes lowered activity and or amounts of antiapoptotic ERK and JNK and enhanced activity of proapoptotic p38. In forward feedback, p38 phosphorylates a specific ser of GR, which further enhances GR activity. GR down-regulates Myc which reduces transcription of JNK and further affects MAPKs via downregulation of various (yellow) other Myc-dependent genes. All arrows indicate direct or indirect regulation. Large right-angle arrows, up or down regulation.. Red indicates increased activity/amount; green, decreased.

Supplementary Material

Table 4.

Genes regulated by Dex only in sensitive CEM clones, compared with regulation by Dex or Dex+Compound E in CUTLL1 cells

| C1-6 and C7-14 | CUTLL1 | CUTLL1 |

|---|---|---|

| A. Decreased by Dex | Dex | Compound E + Dex |

| CELSR3 | + | NR |

| TSR1 | NR | + |

| NOP16 | NR | + |

| NKX2-5 | NR | + |

| PRMT3 | NR | + |

| FAM216A | NR | + |

| CCDC86 | NR | + |

| HES 1 | NR | + |

| BYSL | NR | + |

| APOE | NR | + |

| B. Increased by Dex | Dex | Compound E + Dex |

| DFNA5 | + | NR |

| PTK2B | + | + |

| NR3C1 (GR) | + | + |

| MAP1A | + | + |

| RCA1 | + | + |

| BTG1,2 | + | + |

| SOCS 1 | + | + |

| METTL7A | + | + |

| TUBA4A | NR | + |

| SLA | NR | + |

| BIRC 3 | NR | + |

| RHOBTB3 | NR | + |

| CD53 | NR | + |

| BCL2L11 | NR | + |

| TGFBR2 | NR | + |

| SRGN | NR | + |

| CD69 | NR | + |

| WFS1 | NR | + |

Criteria for inclusion in C1-6, C7-14 gene list: decreased > 2 fold; increased > 2.5 fold (Webb, Miller, Johnson, et al. 2003); in CUTLL1 cells: See (Real and Fernando 2008 dataset citation). Symbols: NR, not regulated, “+”, regulated with statistical significance.

Table 5.

NOTCH pathway genes regulated by Dex after 3 hr in CEM C7-14 or C1-15 cells

| GENE | FOLD CHANGE (p value) | Function | |

|---|---|---|---|

| C7-14 cells | C1-15 cells | ||

| NOTCH | −1.4 (p<0.006) | NS* | Signal transduction |

| JAG1 | +1.97 (p<0.015) | NS | Notch binding, activation |

| NFKBIA | +1.6 (p<0.02) | NS | Decrease NFKB activity |

| ADAM17 | −1.25 (p<0.005) | NS | Cleaves, activates NOTCH |

| SBNO1 | −1.7 (p<0.017) | NS | Homolog, Drosophila |

| ASCL1 | −1.25 (p<0.04) | NS | Transcription factor |

| SBNO1 | NS | +1.17 (p<0.02) | homolog |

NS = not statistically significant.

Highlights.

Gene chips were used to follow the time course of responses to Dexamethasone in GR+ sensitive and resistant leukemic CEM cell clones.

Generally, over the 2–20 hr preceding apoptosis, there was cumulative buildup of induced and repressed genes.

The sensitive clones shared a subset set of these genes, different from the resistant cell.

Myc was down-regulated in the sensitive cells.

The MAPK system could be influenced so as to promote apoptosis by a set of the induced and reduced genes in the sensitive cells.

Acknowledgments

Funded in part by grant 5RO1 CA 41407 from the N.I.H. to EB Thompson. Karon P. Cassidy and Gillian Lynch of the Sealy Ctr. For Structural Biology. UTMB. gave invaluable assistance in developing the figures and with IT issues.

ABBREVIATIONS

- GC

Glucocorticoid

- CyA

cyclosporin

- Dex

Dexamethasone

- MAPK

mitogen activated protein kinase, generic

Footnotes

The text at times uses gene names as found in the cited literature. In the following, the jargon abbreviation or word as used in the text precedes the HGNC official gene symbol in parentheses. GR = GC receptor (NR3C1), ERK (MAPK1), JNK (MAPK9/JNK2, the predominant form in CEM cells), p38 (MAPK14), CaN/calcineurin (PPP3CA/B), calreticulin (CALR), Calrepressin (CALR 1,2,3), GILZ or DSIPI (TSC22D3), ASK1 (MAP3K5), TRX (TXN), GRX (GLRX), protein 14-3-3 (14-3-3), VDUP1 (TXNIP1), AKAP (BRX/AKAP), MRK (ICK/MRK), MKP (DUSP1).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aiyar SE, Park H, Aldo PB, Mor G, Gildea JJ, Miller AL, Thompson EB, Castle JD, Kim S, Santen RJ. TMS, a chemically modified herbal derivative of resveratrol, induces cell death by targeting Bax. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;124:265–77. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0903-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avdi NJ, Nick JA, Whitlock BB, Billstrom MA, Henson PM, Johnson GL, Worthen GS. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha activation of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway in human neutrophils. Integrin involvement in a pathway leading from cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2189–99. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayroldi E, Zollo O, Macchiarulo A, Di Marco B, Marchetti C, Riccardi C. Glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper inhibits the Raf-extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway by binding to Raf-1. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7929–41. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7929-7941.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman G, Wiederrecht GJ, Campbell NF, Martin MM, Bourgeois S. FKBP51, a novel T-cell-specific immunophilin capable of calcineurin inhibition. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4395–402. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman G, Wiederrecht GJ, Chang F, Martin MM, Bourgeois S. Tissue distribution and abundance of human FKBP51, and FK506-binding protein that can mediate calcineurin inhibition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;232:437–43. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becnel LB, Ochsner SA, Darlington YF, McOwiti A, Kankanamge WH, Dehart M, Naumov A, McKenna NJ. Discovering relationships between nuclear receptor signaling pathways, genes, and tissues in Transcriptomine. Sci Signal. 2017;10:eaah6275. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aah6275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan B, Greenan G, McKeon F, Ellenberger T. Identification of a peptide fragment of DSCR1 that competitively inhibits calcineurin activity in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13075–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503846102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen DW, Saha V, Liu JZ, Schwartz JM, Krstic-Demonacos M. Erg and AP-1 as determinants of glucocorticoid response in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncogene. 2013;32:3039–48. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook CN, Hejna MJ, Magnuson DJ, Lee JM. Expression of calcipressin1, an inhibitor of the phosphatase calcineurin, is altered with aging and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;8:63–73. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-8108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfino DV, Agostini M, Spinicelli S, Vito P, Riccardi C. Decrease of Bcl-xL and augmentation of thymocyte apoptosis in GILZ overexpressing transgenic mice. Blood. 2004;104:4134–41. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distelhorst CW. Recent insights into the mechanism of glucocorticosteroid-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:6–19. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driggers PH, Segars JH, Rubino DM. The proto-oncoprotein Brx activates estrogen receptor beta by a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:46792–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106927200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esau C, Boes M, Youn HD, Tatterson L, Liu JO, Chen J. Deletion of calcineurin and myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) binding domain of Cabin1 results in enhanced cytokine gene expression in T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1449–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.10.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garza AS, Miller AL, Johnson BH, Thompson EB. Converting cell lines representing hematological malignancies from glucocorticoid-resistant to glucocorticoid-sensitive: signaling pathway interactions. Leuk Res. 2009;33:717–27. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelebart P, Opas M, Michalak M. Calreticulin, a Ca2+-binding chaperone of the endoplasmic reticulum. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:260–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon JM, Norman MR, Fowlkes BJ, Thompson EB. Dexamethasone induces irreversible G1 arrest and death of a human lymphoid cell line. J Cell Physiol. 1979;98:267–78. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040980203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbour DV, Chambon P, Thompson EB. Steroid mediated lysis of lymphoblasts requires the DNA binding region of the steroid hormone receptor. J Steroid Biochem. 1990;35:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(90)90137-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris CD, Ermak G, Davies KJ. Multiple roles of the DSCR1 (Adapt78 or RCAN1) gene and its protein product calcipressin 1 (or RCAN1) in disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:2477–86. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5085-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holaska JM, Black BE, Love DC, Hanover JA, Leszyk J, Paschal BM. Calreticulin Is a receptor for nuclear export. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:127–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.1.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Borchers CH, Schaller MD, Jacobson K. Phosphorylation of paxillin by p38MAPK is involved in the neurite extension of PC-12 cells. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:593–602. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BH, Ayala-Torres S, Chan LN, El-Naghy M, Thompson EB. Glucocorticoid/oxysterol-induced DNA lysis in human leukemic cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;61:35–45. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(96)00256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Chang L. AP-1--glucocorticoid receptor crosstalk taken to a higher level. J Endocrinol. 2001;169:447–51. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1690447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri T, Takahashi T, Sasaki T, Nakamura S, Hattori S. Protein-tyrosine kinase Pyk2 is involved in interleukin-2 production by Jurkat T cells via its tyrosine 402. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19645–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909828199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kfir-Erenfeld S, Sionov RV, Spokoini R, Cohen O, Yefenof E. Protein kinase networks regulating glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of hematopoietic cancer cells: fundamental aspects and practical considerations. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:1968–2005. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2010.506570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kino T, Souvatzoglou E, Charmandari E, Ichijo T, Driggers P, Mayers C, Alatsatianos A, Manoli I, Westphal H, Chrousos GP, Segars JH. Rho family Guanine nucleotide exchange factor Brx couples extracellular signals to the glucocorticoid signaling system. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9118–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509339200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TK, Baksh S, Cristillo AD, Bierer BE. Calcium- and FK506-independent interaction between the immunophilin FKBP51 and calcineurin. J Cell Biochem. 2002;84:460–71. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Quearry B, Harada H. p38-MAP kinase activation followed by BIM induction is essential for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in lymphoblastic leukemia cells. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:3539–44. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa M, Nishida E, Tanoue T. Identification of the Anti-proliferative protein Tob as a MAPK substrate. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37783–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204506200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino Y, Okamoto K, Yoshikawa N, Aoshima M, Hirota K, Yodoi J, Umesono K, Makino I, Tanaka H. Thioredoxin: a redox-regulating cellular cofactor for glucocorticoid hormone action. Cross talk between endocrine control of stress response and cellular antioxidant defense system. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2469–77. doi: 10.1172/JCI119065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsukawa J, Matsuzawa A, Takeda K, Ichijo H. The ASK1-MAP kinase cascades in mammalian stress response. J Biochem. 2004;136:261–5. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvh134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen M, Keller R, Sussman M, Pumiglia K. Vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated activation of p38 is dependent upon Src and RAFTK/Pyk2. Oncogene. 2004;23:1275–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medh RD, Saeed MF, Johnson BH, Thompson EB. Resistance of human leukemic CEM-C1 cells is overcome by synergism between glucocorticoid and protein kinase A pathways: correlation with c-Myc suppression. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3684–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medh RD, Wang A, Zhou F, Thompson EB. Constitutive expression of ectopic c-Myc delays glucocorticoid-evoked apoptosis of human leukemic CEM-C7 cells. Oncogene. 2001;20:4629–39. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medh RD, Webb MS, Miller AL, Johnson BH, Fofanov Y, Li T, Wood TG, Luxon BA, Thompson EB. Gene expression profile of human lymphoid CEM cells sensitive and resistant to glucocorticoid-evoked apoptosis. Genomics. 2003;81:543–55. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00045-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez J, Turner C, Avraham H, Steinberg SF, Schaefer E, Sussman MA. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis triggered by RAFTK/pyk2 via Src kinase is antagonized by paxillin. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53516–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408475200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Johnson BH, Medh RD, Townsend CM, Thompson EB. Glucocorticoids and polyamine inhibitors synergize to kill human leukemic CEM cells. Neoplasia. 2002;4:68–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Webb MS, Copik AJ, Wang Y, Johnson BH, Kumar R, Thompson EB. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) is a key mediator in glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of lymphoid cells: correlation between p38 MAPK activation and site-specific phosphorylation of the human glucocorticoid receptor at serine 211. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1569–83. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Geng C, Golovko G, Sharma M, Schwartz JR, Yan J, Sowers L, Widger WR, Fofanov Y, Vedeckis WV, Thompson EB. Epigenetic alteration by DNA-demethylating treatment restores apoptotic response to glucocorticoids in dexamethasone-resistant human malignant lymphoid cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2014;14:35. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-14-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molkentin JD. Calcineurin-NFAT signaling regulates the cardiac hypertrophic response in coordination with the MAPKs. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;63:467–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao K, Iwai Y, Miyashita T. RCAN1 is an important mediator of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in human leukemic cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neilson JR, Winslow MM, Hur EM, Crabtree GR. Calcineurin B1 is essential for positive but not negative selection during thymocyte development. Immunity. 2004;20:255–66. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Vu T, Vedin LL, Liu K, Jonsson P, Lin JZ, Candelaria NR, Candelaria LP, Addanki S, Williams C, Gustafsson J, Steffensen KR, Lin CY. Liver × receptor ligands disrupt breast cancer cell proliferation through an E2F-mediated mechanism. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:R51. doi: 10.1186/bcr3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman MR, Thompson EB. Characterization of a glucocorticoid-sensitive human lymphoid cell line. Cancer Res. 1977;37:3785–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner SA, Watkins CM, McOwiti A, Xu X, Darlington YF, Dehart MD, Cooney AJ, Steffen DL, Becnel LB, McKenna NJ. Transcriptomine, a web resource for nuclear receptor signaling transcriptomes. Physiol Genomics. 2012;44:853–863. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00033.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Park JK, Bae KW, Park HT. Protein kinase A activity is required for depolarization-induced proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in PC12 cells. Neurosci Lett. 2000;290:25–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik R, Qi X, Borowicz S, Choubey D, Schultz RM, Han J, Chen G. p38 isoforms have opposite effects on AP-1-dependent transcription through regulation of c-Jun. The determinant roles of the isoforms in the p38 MAPK signal specificity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4831–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt WB, Galigniana MD, Morishima Y, Murphy PJ. Role of molecular chaperones in steroid receptor action. Essays Biochem. 2004;40:41–58. doi: 10.1042/bse0400041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Real PJ, Ferrando AA. NOTCH inhibition and glucocorticoid therapy in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23(8):1374. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Real PJ, Tosello V, Palomero T, Castillo M, Hernando E, Stanchina E, Sulis ML, Barnes K, Sawai C, Homminga I, Meijerink J, Aifantis I, Basso G, Cordon-Cardo C, Walden A, Ferrando A. Gamma-secretase inhibitors reverse glucocorticoid resistance in T-ALL. Nat Med. 2009;15(1):50–58. doi: 10.1038/nm.1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi C, Cifone MG, Migliorati G. Glucocorticoid hormone-induced modulation of gene expression and regulation of T-cell death: role of GITR and GILZ, two dexamethasone-induced genes. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:1182–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi C, Zollo O, Nocentini G, Bruscoli S, Bartoli A, D’Adamio F, Cannarile L, Delfino D, Ayroldi E, Migliorati G. Glucocorticoid hormones in the regulation of cell death. Therapie. 2000;55:165–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna B, Bueno OF, Dai YS, Wilkins BJ, Molkentin JD. Direct and indirect interactions between calcineurin-NFAT and MEK1-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 signaling pathways regulate cardiac gene expression and cellular growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:865–78. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.3.865-878.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saenz GJ, Hovanessian R, Gisis AD, Medh RD. Glucocorticoid-mediated co-regulation of RCAN1-1, E4BP4 and BIM in human leukemia cells susceptible to apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;463:1291–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.06.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S, Wasylyk B. Physiological and pathological consequences of the interactions of the p53 tumor suppressor with the glucocorticoid, androgen, and estrogen receptors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1024:54–71. doi: 10.1196/annals.1321.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JJ, Rhee JG, Suntharalingam M, Walsh SA, Spitz DR, Lee YJ. Role of glutaredoxin in metabolic oxidative stress. Glutaredoxin as a sensor of oxidative stress mediated by H2O2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46566–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206826200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subauste MC, Pertz O, Adamson ED, Turner CE, Junger S, Hahn KM. Vinculin modulation of paxillin-FAK interactions regulates ERK to control survival and motility. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:371–81. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200308011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift J. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a captain of several ships. Vol. 1726. B.Motte; London: Travels into several remote nations of the world, in four parts. [Google Scholar]

- Theodosiou A, Smith A, Gillieron C, Arkinstall S, Ashworth A. MKP5, a new member of the MAP kinase phosphatase family, which selectively dephosphorylates stress-activated kinases. Oncogene. 1999;18:6981–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosti E, Waldbaum L, Warshaw G, Gross EA, Ruggieri R. The stress kinase MRK contributes to regulation of DNA damage checkpoints through a p38 gamma-independent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47652–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409961200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Huang S, Sah VP, Ross J, Brown JH, Han J, Chien KR. Cardiac muscle cell hypertrophy and apoptosis induced by distinct members of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase family. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2161–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb MS, Miller AL, Johnson BH, Fofanov Y, Li T, Wood TG, Thompson EB. Gene networks in glucocorticoid-evoked apoptosis of leukemic cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;85:183–93. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewska M, Pyrzynska B, Kaminska B. Impaired AP-1 dimers and NFAT complex formation in immature thymocytes during in vivo glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. Cell Biol Int. 2004;28:773–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Liu JM, Chen LY. CREG, a new regulator of ERK1/2 in cardiac hypertrophy. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1579–87. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000133717.48334.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuh YS, Thompson EB. Glucocorticoid effect on oncogene/growthgene expression in human T lymphoblastic leukemic cell line CCRF-CEM. Specific c-myc mRNA suppression by dexamethasone. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:10904–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller KI, Jegga AG, Aronow BJ, O’Donnell KA, Dang CV. An integrated database of genes responsive to the Myc oncogenic transcription factor: identification of direct genomic targets. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R69. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-10-r69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, He X, Liu W, Lu M, Hsieh JT, Min W. AIP1 mediates TNF-alpha-induced ASK1 activation by facilitating dissociation of ASK1 from its inhibitor 14-3-3. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1933–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI17790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Blattman JN, Kennedy NJ, Duong J, Nguyen T, Wang Y, Davis RJ, Greenberg PD, Flavell RA, Dong C. Regulation of innate and adaptive immune responses by MAP kinase phosphatase 5. Nature. 2004;430:793–7. doi: 10.1038/nature02764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Insel PA. The pro-apoptotic protein Bim is a convergence point for cAMP/protein kinase A- and glucocorticoid-promoted apoptosis of lymphoid cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20858–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310643200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F, Medh RD, Thompson EB. Glucocorticoid mediated transcriptional repression of c-myc in apoptotic human leukemic CEM cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;73:195–202. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00080-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B, Wang ZX, Zhao Y, Brautigan DL, Zhang ZY. The specificity of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 dephosphorylation by protein phosphatases. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31818–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203969200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.