Abstract

Obesity or a high-fat diet represses the endoribonuclease activity of inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), a transducer of the unfolded protein response (UPR) in cells under endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. An impaired UPR is associated with hepatic steatosis and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which is caused by lipid accumulation in the liver. Here, we found that IRE1α was critical to maintaining lipid homeostasis in the liver by repressing the biogenesis of microRNAs (miRNAs) that regulate lipid mobilization. In mice fed normal chow, the endoribonuclease function of IRE1α processed a subset of precursor miRNAs in the liver, including those of the miR-200 and miR-34 families, such that IRE1α promoted their degradation through the process of regulated IRE1-dependent decay (RIDD). A high-fat diet in mice or hepatic steatosis in patients was associated with the S-nitrosylation of IRE1α and inactivation of its endoribonuclease activity. This resulted in an increased abundance of these miRNA families in the liver and, consequently, a decreased abundance of their targets, which included peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) and the deacetylase sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), regulators of fatty acid oxidation and triglyceride lipolysis. IRE1α deficiency exacerbated hepatic steatosis in mice. The abundance of the miR-200 and miR-34 families was also increased in cultured, lipid-overloaded hepatocytes and in the livers of patients with hepatic steatosis. Our findings reveal a mechanism by which IRE1α maintains lipid homeostasis through its regulation of miRNAs, a regulatory pathway distinct from the canonical IRE1α-UPR pathway under acute ER stress.

Keywords: IRE1α, Unfolded Protein Response, microRNA, Lipid metabolism, Fatty liver

Introduction

Excessive dietary lipid intake is associated with increased incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a spectrum of diseases ranging from steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and eventually to hepatocellular carcinoma. Dysfunction of the endoplasm reticulum (ER) has been proposed to play a crucial role in both the onset of steatosis and progression to NASH (1, 2). Environmental stressors or pathophysiological alterations can challenge protein folding homeostasis in the ER, impose stress on the ER, and subsequently lead to accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the ER lumen. This triggers the unfolded protein response (UPR), leading to activation of three major ER-transmembrane stress sensors, including the endoribonuclease (RNase) inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1α), protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK), and activating transcription factor (ATF) 6 (3, 4). The UPR represents an important pro-survival response as it not only promotes ER protein homeostasis but also interacts with many different signaling pathways to maintain inflammatory and metabolic equilibrium under stress conditions (5–7). When UPR machinery is damaged or the cellular stress exceeds the capacity of UPR, ER stress can trigger pro-inflammatory response or cell apoptosis that is critically involved in the pathogenesis of a variety of diseases (3, 7, 8). Among the three UPR pathways, the IRE1α/XBP1 pathway is the most evolutionarily conserved one. Upon ER stress, IRE1α splices the mRNA encoding X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) via its RNase activity, thereby generating functional spliced XBP1 (XBP1s) to activate gene expression of a subset of UPR-associated regulators. In addition to splicing the XBP1 mRNA, IRE1α can process select mRNAs, leading to their degradation, a process known as Regulated IRE1-dependent Decay (RIDD) (9–11). Recent studies suggested that IRE1α undergoes dynamic conformational changes and switches its functions depending on the duration of ER stress (12, 13). In response to acute ER stress, IRE1α quickly forms oligomeric clusters to initiate Xbp1 mRNA splicing (14). Additionally, the cytosolic domain of IRE1α can act as a scaffold to recruit cytosolic adaptor proteins, for example, TNF receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2), leading to activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-mediated signaling pathway associated with inflammatory and metabolic diseases (8, 15). We and others previously demonstrated that IRE1α/XBP1 UPR pathway protects hepatic lipid accumulation and liver function against hepatic injuries induced by acute ER stress (2, 16–19). These studies showed that IRE1α can modulate hepatic de novo lipogenesis or promote very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) assembly and secretion through activation of XBP1 or RIDD pathway. Most recently, Yang et al. revealed that obesity and associated chronic inflammation repress IRE1α RNase activity by S-nitrosylation of IRE1α (20). Consequently, obesity-induced S-nitrosylation of IRE1α impairs IRE1α-mediated Xbp1 mRNA splicing and RIDD activity.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression at the posttranscriptional level by base-pairing to their target mRNAs, thereby mediating mRNA decay or translational repression (21, 22). Maturation of miRNAs involves transcription of approximately 70-nucleotide RNA intermediates (pre-miRNAs) that are transferred to the cytoplasm and further processed to mature miRNA of 20 – 22 nucleotides long (23). miRNAs control diverse pathways depending on cell types and micro-environment. Of particular note, pre-miRNAs have been reported to be RNA cleavage substrates of the IRE1α RNase activity through the RIDD pathway (10, 24). Here, we investigated whether the IRE1α-miRNA regulatory pathway is involved in hepatic lipid metabolism and hepatic steatosis and found that IRE1α deficiency affects the biogenesis of select miRNAs and, consequently, the abundance of metabolic enzymes that increase hepatic lipid accumulation that contributes to hepatic steatosis.

Results

Hepatocyte-specific Ire1α−/− mice develop severe hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance under HFD

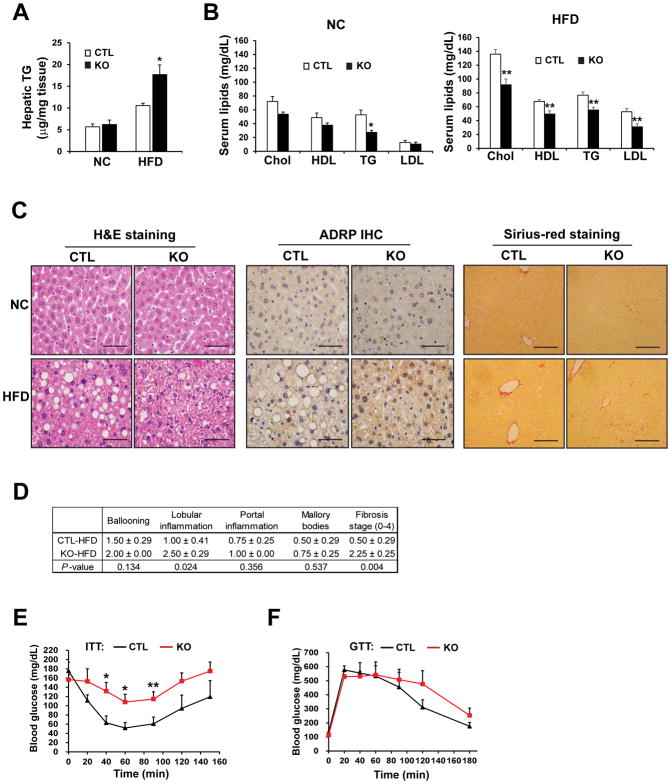

To investigate the pathophysiological roles of IRE1α in hepatic lipid metabolism during exposure to excessive nutrients, we fed hepatocyte-specific Ire1α−/− and control mice (Ire1αfl/fl) normal chow (NC) or a high-fat diet (HFD; 45% kcal fat) for 20 weeks. Under NC, deletion of IRE1α in hepatocytes was associated with modest changes in lipid profiles; only serum triglyceride levels were significantly reduced in the Ire1α−/− mice (Fig. 1, A and B). However, after HFD, the Ire1α−/− mice displayed significantly higher amounts of hepatic triglycerides (Fig. 1A) but lower amounts of serum triglycerides, cholesterol, LDL, and HDL, compared to the control mice (Fig. 1B). Histological analysis of the livers, by immunohistochemical staining for adipose differentiation-related protein (ADRP) (Fig. 1C) as well as expression of ADRP protein measured by Western blot analysis (fig S1A), revealed that HFD-fed Ire1α−/− mice had extensive hepatic micro-vesicular steatosis characterized by the accumulation of small lipid droplet particles in the cytosol. In comparison, the HFD-fed control (Ire1αfl/fl) mice developed less severe macro-vesicular steatosis characterized by engorgement of the hepatocyte by large fat globules. These observations suggest that IRE1α deletion results in severe hepatic steatosis with hypolipidemia.

Fig. 1. Hepatocyte-specific Ire1α−/− mice on a high-fat diet exhibit NASH and insulin resistance.

(A) Hepatic triglycerides (TG) in Ire1α−/− (KO) and control (CTL, Ire1αfl/fl) mice fed either normal chow (NC) or a high-fat diet (HFD) for 20 weeks. *p<0.05 vs. CTL. (B) Serum cholesterol (Chol), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and TGs in the KO and CTL mice described in (A). (C) H&E staining, ADRP immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining, and Sirius-red staining of collagen deposition with liver tissue sections from the KO and CTL mice described in (A). Scale bar: 5μm. (D) Table showing the quantification (means ± S.D.) of hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in IRE1α KO and CTL mice fed a HFD for 20 weeks. (E) Analysis of insulin tolerance tests in IRE1α KO and CTL mice fed a HFD for 19 weeks, fasted for 4 hours, and then intraperitoneally injected with 0.75mU/gram body weight of human insulin. (F) Analysis of glucose tolerance tests in IRE1α− KO and CTL mice fed a HFD for 11 weeks, fasted for 14 hours, and then injected with 2mg glucose/gram body weight. Data are mean ± SEM from n=8 (KO) or 4 (CTL) mice per group; * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 by by unpaired 2-tailed Student’s T-Test (A–B, D–F).

Next, we evaluated whether Ire1α−/− livers developed a non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)-like phenotype. Histological analyses based on haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and Sirius-red staining for hepatic collagen deposition (Fig. 1C) identified increased hepatic lobular inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning, and fibrosis in the livers of HFD-fed Ire1α−/− mice, compared to those from HFD-fed control mice. Hepatic inflammation and fibrosis scoring indicated that the HFD-fed Ire1α−/− mice possessed a NASH-like phenotype (Fig. 1D). Because NASH is associated with type-2 diabetes, we evaluated the impact of hepatocyte-specific IRE1α deficiency on glucose homeostasis. On a NC diet, Ire1α−/− mice were superficially indistinguishable from the control mice in insulin sensitivity or in defending blood glucose (fig. S1, B and C). However, after 19 weeks on a HFD, the Ire1α−/− mice showed decreased insulin sensitivity, as reflected by higher serum glucose levels after i.p. injection of insulin (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, in response to i.p injection of glucose, the HFD-fed Ire1α−/− mice displayed discernable reduction in glucose tolerance, compared to the control animals (Fig. 1F). Additionally, the Ire1α−/− mice gained more body weight after 6 weeks on a HFD (fig. S1D). In sum, these data suggest that in the absence of IRE1α in hepatocytes, mice are prone to developing metabolic disorders, characterized by hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance.

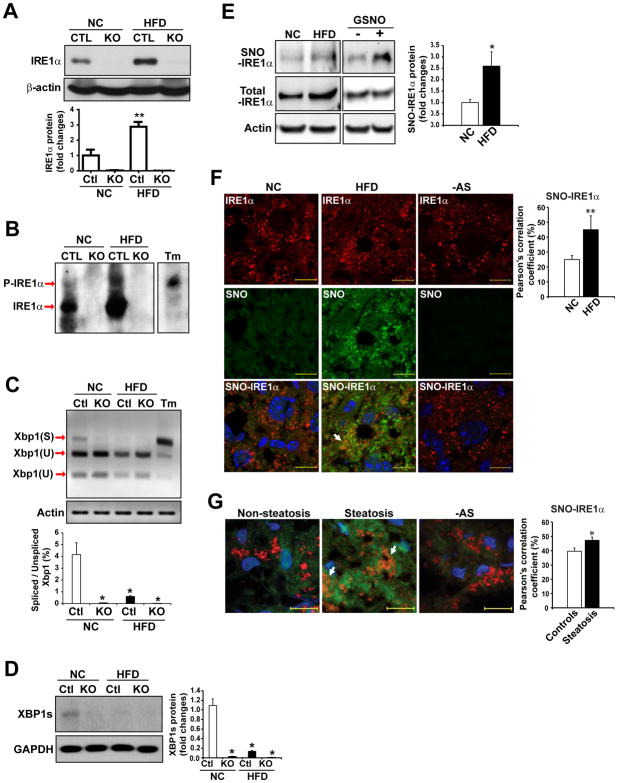

IRE1α RNase activity is impaired in the livers of HFD-fed mice and in patients with hepatic steatosis

Next, we sought to understand the role(s) of IRE1α within the liver during nutrient excess. IRE1α is a bifunctional enzyme that processes a kinase domain and a RNase domain. First, we measured IRE1α activity in the liver of NC- or HFD-fed mice. After 20 weeks of HFD feeding, the amount of total IRE1α protein in mouse livers was increased (Fig. 2A), suggesting IRE1α expression was up-regulated by HFD. Furthermore, the amount of phosphorylated IRE1α protein, as determined by Western blot analysis through a Phos-Tag SDS-PAGE (25), was also increased in the liver of mice after HFD (Fig. 2B). Under ER stress, IRE1α is auto-phosphorylated to cause conformational shifts that increase its RNase activity to splice the Xbp1 mRNA or select mRNAs or miRs through the RIDD pathway (9, 11, 26). Contrary to the increased protein abundance of IRE1α, the amounts of the spliced Xbp1 mRNA (Fig. 2C) and XBP1 protein (Fig. 2D) were repressed in the liver of mice under HFD, compared to that of mice under NC, suggesting that IRE1α RNase activity was de-activated in the liver under HFD. The obese condition reportedly represses IRE1α RNase activity and Xbp1 mRNA splicing by S-nitrosylation of IRE1α, whereas the same condition increases IRE1α phosphorylation (20). S-nitrosylation, the covalent attachment of a nitrogen monoxide group to the thiol side chain of cysteine residues, represents an important mechanism for dynamic, posttranslational modulation of protein activities (27). We utilized a biotin-switch method to enrich S-nitrosylated proteins in the livers of NC- or HFD-fed mice, and then examined S-nitrosylated IRE1α proteins in the mouse livers by Western blot analysis. Through this approach, we detected significantly enhanced S-nitrosylation of IRE1α in the livers of HFD-fed mice, compared to that of NC-fed mice (Fig. 2E). Immunoblotting analysis showed that expression of total IRE1α protein in the livers of HFD-fed mice was higher than in those of NC-fed mice (Fig. 2, A and E). It is possible that HFD-induced S-nitrosylation of IRE1α repressed IRE1α enzymatic activity, which stimulated expression of IRE1α protein in the liver as a feedback regulation. Further, we utilized an in situ immunofluorescence staining approach to visualize S-nitrosylated IRE1α proteins in the livers of NC- or HFD-fed mice. Consistent with the biotin-switch Western blot analysis, in situ immunofluorescence staining showed that the levels of nitrosylated IRE1α proteins were significantly increased in the liver hepatocytes of HFD-fed mice (Fig. 2F). The specificity of S-nitrosylated IRE1α staining signals was confirmed by immunofluorescent staining of S-nitrosylated IRE1α in liver tissues from S-Nitrosoglutathione Reductase (GSNOR)-deficient or inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)-deficient mice fed a HFD (fig. S2). Next, we evaluated whether hepatic steatosis promotes S-nitrosylation of IRE1α in human patients with metabolic complications. In situ detection of S-nitrosylated IRE1α proteins in steatotic and nonsteatotic liver samples from patients indicated that the amount of S-nitrosylated IRE1α protein was significantly increased in the hepatocytes from patients with hepatic steatosis (Fig. 2G). Together, these data indicated that S-nitrosylation of IRE1α is increased in the fatty livers of both human and mouse and that impaired IRE1α RNase activity in the fatty livers may result from S-nitrosylation modification.

Fig. 2. IRE1α RNase activity is suppressed in the fatty livers of HFD-fed mice or human patients.

(A) Western blot analysis of IRE1α protein abundance in the livers of hepatocyte-specific IRE1α KO and CTL mice fed NC or a HFD for 20 weeks. (B) Western blot analysis through Phos-tag SDS-PAGE for phosphorylated and un-phosphorylated IRE1α in the livers of IRE1α KO and CTL mice fed NC or a HFD. Tm: tunicamycin, a positive control for ER-stress-induced phosphorylation of IRE1α. (C) Quantitative electrophoretic analysis of spliced and unspliced Xbp1 mRNA in the livers of the IRE1α KO and CTL mice fed NC or a HFD. Xbp1 cDNAs were amplified by semi-quantitative RT-PCR from the total RNAs isolated from the mouse livers, followed by PstI restriction enzyme digestion. Tm-treated hepatocytes (5 μg/ml) were a positive control. Xbp1(S): spliced Xbp1; Xbp1(U): un-spliced Xbp1. (D) Western blot analysis of spliced XBP1 protein (XBP1s) abundance in IRE1α KO and CTL mice fed NC or a HFD. GAPDH, loading control. (E) Abundance of S-nitrosylated (SNO) IRE1α, total IRE1α, and β-actin in the livers of NC- and HFD-fed mice. SNO-IRE1α protein was enriched by a biotin-switch method and detected by Western blot analysis. Mouse liver protein lysate incubated with S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO, 100 μM; +) or without (−) are positive and negative controls, respectively. (F and G) Representative images (63×) of staining for SNO (green) and IRE1α (red) in the livers from NC- and HFD-fed mice (F) and from patients with or without hepatic steatosis (G). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Arrows indicate colocalization of SNO and IRE1α, quantified as inferred SNO-IRE1α in the graphs (right). Ascorbate-omitted staining (−AS) are negative controls. Scale bars: 10μm. Data are means ± SEM of n=4 mice per group (A–E) or n=8 mice or patients per group (F and G). * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 by unpaired 2-tailed Student’s t-test.

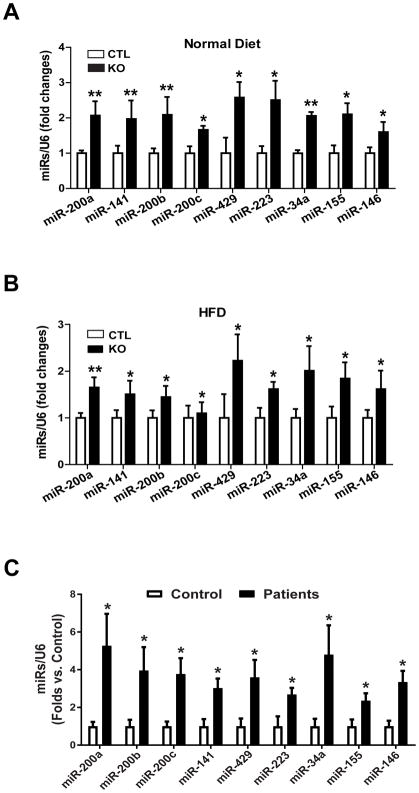

IRE1α deficiency increases the abundance of a subset of miRNA clusters in the steatotic livers of HFD-fed mice and patients

Because HFD impairs IRE1α RNase activity in processing Xbp1 mRNAs, we wondered whether the non-canonical IRE1α-RIDD pathway is associated with the NASH-like hepatic steatosis developed in the Ire1α−/− mice under HFD. In particular, IRE1α can process select precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs), leading to their degradation through the RIDD pathway (10) (fig. S3A). We therefore tested for hepatic-specific, IRE1α-dependent changes to the miRNAs known to regulate metabolism in mouse livers. Liver- and pathway-specific miRNA quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) array revealed that expression of a subset of miRNAs, which function as important regulators in lipid metabolism, was increased in the livers of Ire1α−/− mice fed NC or a HFD (Fig. 3, A and B, fig. S3B, and table S1). These include miR-200 family members (miR-200a/b/c, miR-141, and miR-429), miR-34, miR-223, miR-155, and miR-146. Additionally, up-regulation of these miRNAs was observed in the livers of HFD-fed mice and in oleic acid-loaded hepatocytes (fig. S3, C and D). These data suggested that a subset of miRNAs, which function as facilitators of hepatic steatosis, were increased in the livers of HFD-fed mice and that IRE1α plays a role in repressing these miRNAs. Because a HFD decreased IRE1α RNase-mediated splicing of Xbp1 mRNA, the increased abundance of miRNAs in fat-loaded livers or hepatocytes was likely the result of impaired miRNA degradation mediated by the RNase activity of IRE1α.

Fig. 3. IRE1α deficiency results in an increased abundance of a subset of miRNA clusters in the steatotic livers of HFD-fed mice or human diabetic patients.

(A and B) miRNA-qPCR analysis of miRNA cluster expression in the livers of IRE1α KO and CTL mice fed NC (A) or a HFD (B) for 20 weeks. (C) miRNA-qPCR analysis of miRNA cluster expression in the livers of human patients with or without hepatic steatosis s. Data in all panels are means ± SEM from n=4 individuals per group. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 vs controls by unpaired 2-tailed Student’s T-Test.

Because impaired IRE1α RNase activity, caused by IRE1α nitrosylation, and up-regulation of select miRNAs were detected in the steatotic livers of HFD-fed mice, we wondered whether these select miRNAs were also up-regulated in the livers of human patients with hepatic steatosis, in which S-nitrosylation of IRE1α was significantly increased (Fig 2G). We examined the profiles of miRNA expression in liver tissue from patients with hepatic steatosis and from donors with non-steatotic livers. Similar to the steatotic livers from HFD-fed mice, human steatotic livers displayed a greater abundance of miR-200 family members (miR-200a/b/c, miR-141, and miR-429), miR-34, miR-223, miR-155, and miR-146, compared to the non-steatotic controls (Fig 3C), thus confirming the up-regulation of the select miRNAs and impaired IRE1α RNase activity in human fatty livers.

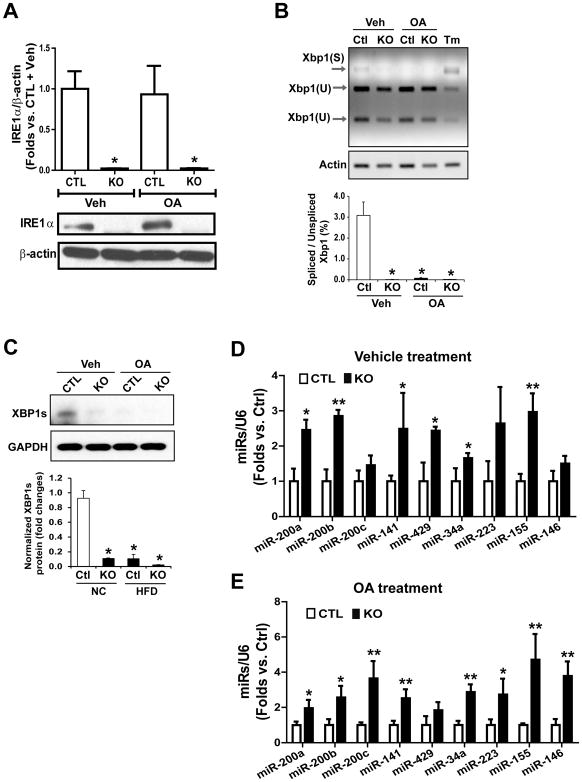

IRE1α-deficient hepatocytes have increased abundance of the miR-34 and miR-200 families and accumulate more neutral lipids

To confirm the role of IRE1α in preventing lipid accumulation in hepatocytes, we isolated hepatocytes from Ire1α−/− and control (Ire1αfl/fl) mice and incubated them with oleic acid to induce hepatic steatosis in vitro (28). Consistent with the in vivo experiments, the abundance of IRE1α protein was up-regulated in the oleic acid-loaded hepatocytes (Fig. 4A), whereas the amounts of the spliced Xbp1 mRNA and XBP1 protein in hepatocytes were suppressed by the treatment with oleic acid (Fig. 4, B and C). Supporting the role of IRE1α in repressing the miR-200 and miR-34 families in the liver (Fig. 2), the expression of the miRNA members (namely miR-200a/b/c, miR-141, miR-429, miR34a, miR223, miR-155 and miR-146), were up-regulated in both control and oleic acid-treated hepatocytes upon deletion of Ire1α (Fig. 4, D and E). To verify hepatic steatosis-associated alterations of IRE1α and the select miRNAs, we incubated Ire1α−/− and control mouse hepatocytes with palmitate, a saturated fatty acid that can induce in vitro hepatic steatosis with additional hepatic injuries (28). Consistent with the observations with oleic acid, palmitate challenge led to down-regulation of IRE1α RNase activity, as reflected by decreased splicing of Xbp1 mRNA (fig. S4, A and B) and up-regulation of the select miRNAs, including the miR-200, miR-34, miR-155, miR-233, and miR-146 families (fig. S4, C and D).

Fig. 4. IRE1α represses levels of miR-200 and miR-34 families in hepatocytes.

IRE1α KO and wild-type control (CTL) mouse hepatocytes were incubated with oleic acid (OA; 500μM) or vehicle [Veh; 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA)] for 24 hours. (A) Western blot analysis of IRE1α abundance in IRE1α KO and CTL hepatocytes. β-actin, loading control. (B) Quantitative electrophoretic analysis of spliced and un-spliced Xbp1 mRNA in IRE1α KO and CTL mouse hepatocytes incubated with OA or vehicle. Xbp1 cDNAs were amplified by semi-quantitative RT-PCR, followed by PstI restriction enzyme digestion. Xbp1(S): spliced Xbp1; Xbp1(U): un-spliced Xbp1. (C) Western blot analysis of spliced XBP1 protein (XBP1s) abundance in IRE1α KO and CTL hepatocytes incubated with OA or vehicle. GAPDH: loading control. (D and E) miRNA-qPCR analysis of miRNA cluster expression in IRE1α KO and CTL hepatocytes loaded with OA or vehicle. Data in all panels are means ± SEM of n=3 biological replicates * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 vs controls by unpaired 2-tailed Student’s T-Test.

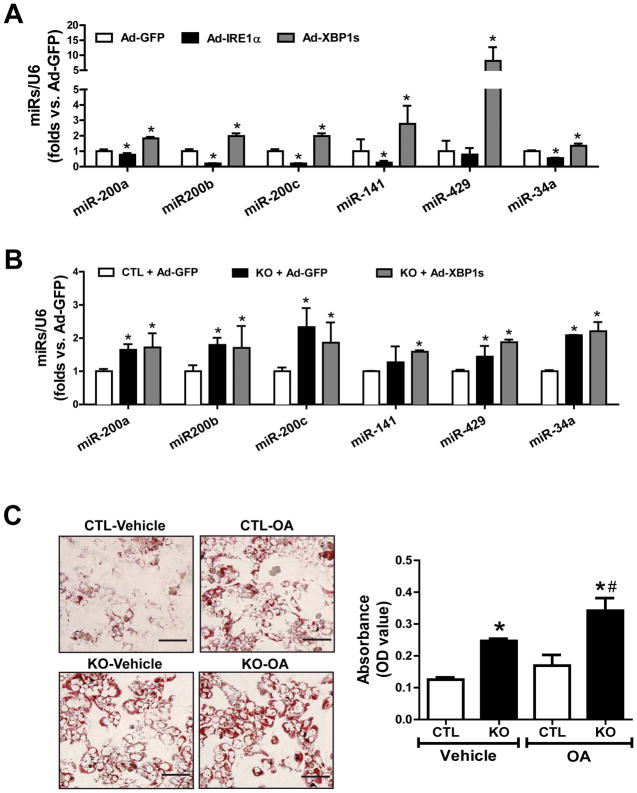

We then confirmed that IRE1α-mediated suppression of miRNA biogenesis was independent of IRE1α’s canonical signaling transduction through activating XBP1, because over-expression of IRE1α, but not the activated/spliced form of XBP1 (XBP1s) or GFP significantly reduced the abundance of miR-200 and miR-34 family members in the control hepatocytes (Fig. 5A). Over-expression of XBP1s also failed to repress up-regulation of miR-200 and miR-34 clusters in Ire1α−/− hepatocytes (Fig. 5B). In fact, XBP1s over-expression increased the abundance of miR-200 and miR-34 in hepatocytes. Further dose-response and time course experiments indicated that XBP1s overexpression at different doses or for different durations did not exhibit any effect on down-regulating miR-200 and miR-34 in Ire1α−/− hepatocytes (fig. S5), confirming the role of IRE1α in suppressing the select miRs in hepatocytes through a regulatory mechanism independent of XBP1.

Fig. 5. IRE1α-deficient hepatocytes accumulate more neutral lipids and represses miR-200 and miR-34 in a manner independent of XBP1.

(A and B) Over-expression of IRE1α, activated XBP1, or GFP control in IRE1α KO and CTL hepatocytes using adenoviral-based expression system (100 MOI) for 48 hours. miRNA-qPCR analysis of levels of miR-200 and miR-34 family members in the hepatocytes. (C) Representative images and quantification of Oil-red O staining of lipid droplets in IRE1α KO and CTL hepatocytes after incubation with OA or vehicle (0.5% BSA) for 24 hours. Scale bar: 5μm. The quantification was determined by eluting the Oil Red O dye in isopropanol and the optical density (OD) was read at 500 nm. Data are means ± SEM of n=3 biological replicates. *p<0.05 vs. CTL+Ad-GFP (A–B) or CTL+vehicle (C), #p<0.05 vs. CTL+OA (C).

Additionally, we examined the impact of IRE1α deletion on hepatic lipid accumulation using in vitro cultured hepatocytes. Consistent with the hepatic steatosis phenotype of Ire1α−/− mice, increased lipid accumulation was observed in oleic-treated Ire1α−/− hepatocytes (Fig. 5C). Even without the addition of oleic acid, a greater amount of neutral lipids accumulated in Ire1α−/− hepatocytes than in control hepatocytes.

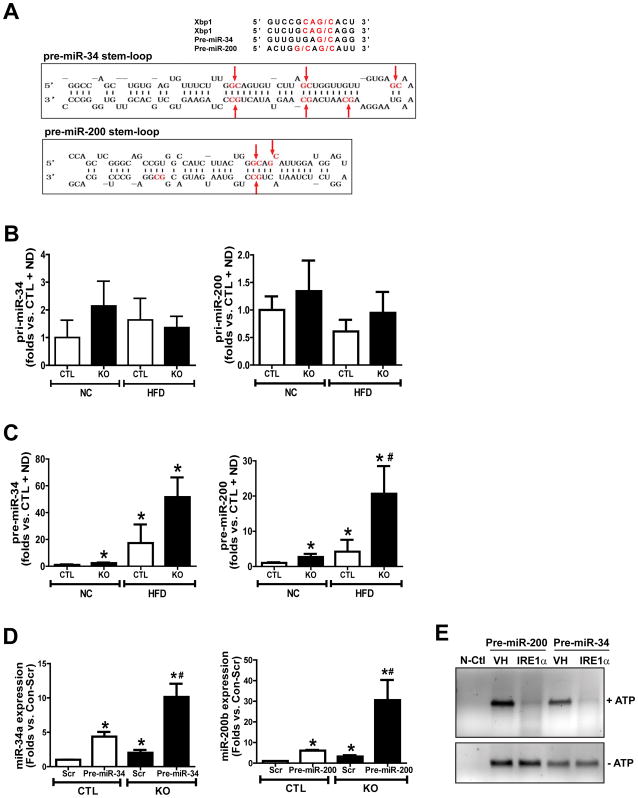

IRE1α suppresses the biosynthesis of miR-34 and miR-200 at the pre-miRNA level

Studies have suggested that IRE1α can process mRNA or pre-miRs by recognizing the G/C cleavage site in RNA stem-loops (10) (fig. S3A). IRE1α-cleaved miRNAs cannot be processed by Dicer for the maturation process; as a consequence, these miRNAs are destined for degradation. Bioinformatics analysis indicated that pre-miR-200 and pre-miR-34, the amounts of which were up-regulated in Ire1α−/− liver tissues or hepatocytes, possess G/C cleavage sites in their stem-loop structures that are potentially recognized by IRE1α (Fig. 6A). To determine whether IRE1α regulates miRNA expression at the pre-miR level, we assessed the abundance of the primary miRs (pri-miRNAs) and the stem-loop-containing pre-miRNAs for miR-200 and miR-34 in the livers of Ire1α−/− and control mice when fed a NC diet or a HFD. Whereas the abundances of pri-miR-34 and pri-miR-200 were similar in Ire1α−/− and control livers (Fig. 6B), the abundances of pre-miR-34 and pre-miR-200 in Ire1α−/− livers were significantly higher than those in the control livers under NC or HFD conditions (Fig. 6C). These results suggested that IRE1α suppresses miR-34 and miR-200 at the pre-miRNA level. Next, we over-expressed pre-miR-200 and pre-miR-34 in Ire1α−/− and control hepatocytes, and then measured the abundance of mature miR-200 and miR-34. Expression of pre-miR-34 and pre-miR-200 yielded significantly greater amounts of mature miR-34a and miR-200b in the Ire1α−/− cells than it did in the control cells (Fig. 6D), thus confirming the role of IRE1α in suppressing miR-34 and miR-200 biogenesis at the pre-miRNA level.

Fig. 6. IRE1α processes pre-miR-200 and pre-miR-34 and leads to their degradation.

(A) The sequence motif and stem-loop structures for the IRE1α cleavage sites within human XBP1 mRNA, pre-miR-34 and pre-miR-200. Lower pictures show the predicted secondary structures for miR-34 and miR-200 with their potential IRE1α cleavage sites (G/C sites marked by red arrows). (B–C) qPCR analyses of expression levels of pri-miR-34, pri-miR-200, pre-miR-34, and pre-miR-200 in the livers of IRE1α KO and CTL mice under NC or HFD for 20 weeks. Data are means ± SEM (n=4 mice per group). * p<0.05 vs. CTL + NC; # p<0.05 vs. CTL + HFD by unpaired 2-tailed Student’s T-Test. (D) miRNA-qPCR analysis of the abundance of mature miR-34 and miR-200 in IRE1α KO and CTL hepatocytes transfected with plasmid vector expressing pre-miR-34, pre-miR-200, or scramble oligonucleotides (Scr). * Data are means ± SEM (n=3 biological replicates); p<0.05 vs. CTL + Scr; # p<0.05 vs. CTL + pre-miR-34 or pre-miR-200. (E) In vitro cleavage of pre-miR-200 and pre-miR-34 by recombinant IRE1α protein (1 μg each), incubated at 37°C with ATP (2mM), or not as controls, and resolved on a 1.2% agarose gel. N-Ctl, negative control reaction containing no pre-miRNA; VH, vehicle buffer containing no IRE1α protein. The image is a representative of 3 experiments.

To test whether IRE1α directly processes the select miRNAs, we performed in vitro cleavage analysis by incubating pre-miR-200 or pre-miR-34 oligonucleotides with the purified recombinant human IRE1α protein. In the presence of ATP, IRE1α processed both pre-miR-200 and pre-miR-34, leading to their degradation (Fig. 6E). This result validated the role of IRE1α as an RNase that processes pre-miR-34 and pre-miR-200 and leads to their decay through the RIDD pathway.

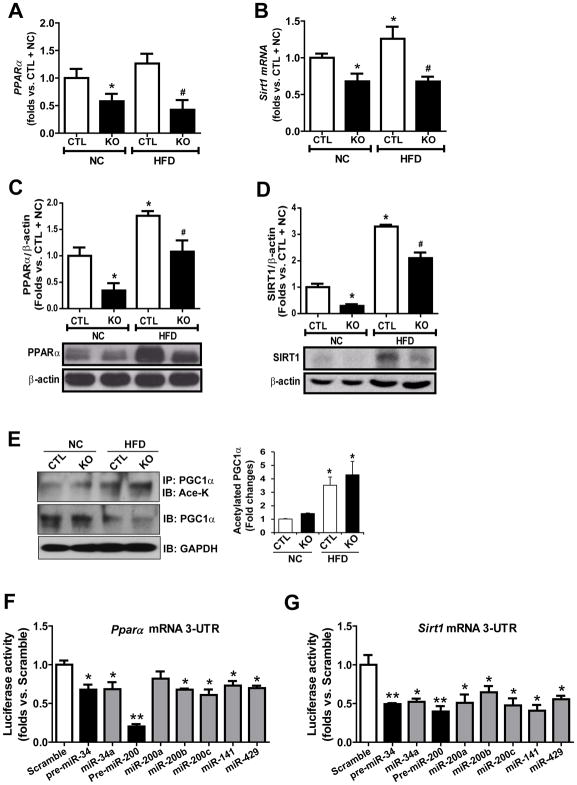

PPARα and SIRT1, the targets of miR-34 and miR-200, are repressed by IRE1α deficiency in the liver

We examined the expression of genes encoding the key regulators or enzymes involved in hepatic lipid metabolism in the livers of Ire1α−/− and control mice under NC or HFD conditions. Whereas the expression of most known metabolic regulators were comparable in the Ire1α−/− and control mouse livers (fig. S6A), qPCR and Western blot analyses revealed that both protein and mRNA abundances of PPARα and SIRT1, the master regulators of hepatic fatty acid oxidation and triglyceride lipolysis (29, 30), were significantly reduced in the livers of Ire1α−/− mice or HFD-fed control mice (Fig. 7, A–D). To confirm the defect of hepatic PPARα caused by IRE1α deficiency, we examined the expression of the PPARα-target genes related to fatty acid oxidation, including Acox1, Cpt1, Cyp4a10, and Cyp4a14, in the livers of Ire1α−/− and control mice under NC or HFD conditions. Expression of Acox1, Cpt1, Cyp4a10, and Cyp4a14 was reduced in Ire1α−/− and control mouse livers under HFD (fig. S6B), suggesting that impaired IRE1α activity may lead to repression of hepatic fatty acid oxidation and hepatic steatosis. Furthermore, we examined the acetylation of PGC1α, a PPAR transcriptional co-activator that is deacetylated and activated by the deacetylase SIRT1 (31), in the livers of Ire1α−/− and control mice under NC or HFD conditions. Immunoprecipitation (IP)-Western blot analysis showed that the abundance of acetylated PGC1α protein in the livers of Ire1α−/− mice or HFD-fed control mice was increased, compared to that of NC-fed control mice (Fig. 7E). The abundance of acetylated PGC1α in HFD-fed Ire1α−/− mice were increased more robustly, compared to that of NC-fed Ire1α−/− mice or HFD-fed control mice. This was consistent with the reduction of SIRT1 and PPARα and increased hepatic steatosis in Ire1α−/− livers, given that SIRT1-mediated deacetylation and activation of PGC1α function is an important regulatory axis of fatty acid oxidation (31). Together, these results prompted us to speculate that suppression of PPARα and SIRT1 in the absence of IRE1α may account for exacerbated hepatic steatosis observed in the Ire1α−/− mice.

Fig. 7. IRE1α deficiency represses expression of PPARα and SIRT1 through increased abundance of miR-34 and miR-200.

(A–D) Abundance of PPARα and SIRT1 mRNA (A and B, by qPCR) and protein (C and D, by Western blot) in livers from hepatocyte-specific IRE1α KO and CTL mice fed NC or a HFD diet for 20 weeks. Data are means ± SEM (n=4 mice per group); * p<0.05 vs. CTL + NC; # p<0.05 vs. CTL + HFD by unpaired 2-tailed Student’s T-Test (A–G). (E) IP-Western blot analysis of acetylated PGC1α abundance in the livers from IRE1α KO and control mice fed NC or a HFD. Mouse liver protein lysates were immunoprecipitated with the anti-PGC1α antibody, followed by immunoblotting (IB) with the anti-acetyl-lysine (Ace-K) antibody. Data are means ± SEM (n=4 mice per group); * p<0.05 vs. CTL + NC. (F and G) Luciferase reporter assay of suppressive activities of miR-200 or miR-34 family members on the reporter driven by the human PPARα mRNA 3′-UTR (F) or SIRT1 mRNA 3′-UTR (G). Attenuation of luciferase activity was interpreted as direct binding of miRNAs to the 3′-UTR. Data are means ± SEM (n=3 biological replicates); * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 vs. scramble co-transfection with PPARα or SIRT1 mRNA 3′-UTR reporter vector.

Through miRNA base alignment analyses, we identified high-confidence matches for binding sequences of miR-34 and miR-200 family members (miR-200a/b/c, miR-141 and miR-429) in the 3′-UTRs of the Pparα and Sirt1 mRNAs (Fig S7). This implicated that miR-200 and miR-34 may attenuate expression of PPARα and SIRT1 by binding to the 3-UTRs of the Pparα or Sirt1 mRNAs. To test this possibility, we performed 3-UTR reporter analysis with the hepatocytes expressing luciferase under the control of the 3-UTRs of the Pparα or Sirt1 mRNA. Expression of pre-miR-200, pre-miR-34, or individual matured miR-200 or miR-34 family members significantly suppressed translation of the Pparα or Sirt1 mRNA (Fig. 7, F and G), thus confirming that Pparα and Sirt1 are the direct targets of miR-200 and miR-34. Note that expression of pre-miR-200 or pre-miR-34 exerted much stronger effects of repression on Pparα or Sirt1 mRNA translation, compared to expression of individual miR-200 or miR-34 family members. This is likely due to the synergistic effect of miRNA family members generated from the same pre-miRNA.

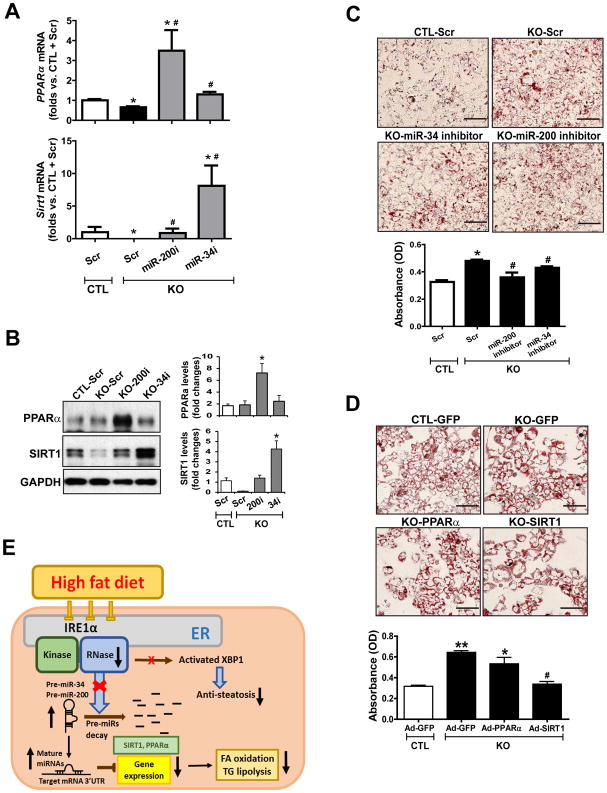

Inhibition of miR-200 or miR-34 can restore PPARα and SIRT1 abundance and relieve hepatic steatosis in Ire1α-null hepatocytes

To determine the extent by which miR-200 or miR-34 suppresses the abundance of PPARα and SIRT1 in the context of IRE1α deficiency, we tested whether inhibiting miR-200 or miR-34 can restore the abundance of PPARα and SIRT1 in Ire1α−/− hepatocytes. Ire1α−/− hepatocytes incubated with oleic acids and either miR-200 or miR-34 antagomir had significantly increased abundance of levels of PPARα and SIRT1 at both the mRNA and protein levels, compared to cells incubated with the scramble control oligonucleotide (Fig. 8, A and B). Similarly, incubation with the miR-200 or miR-34 antagomir also increased the abundance of Pparα and Sirt1 transcripts in Ire1α−/− hepatocytes incubated with palmitate (fig. S8, A and B). These results indicate that increased amounts of miR-200 and miR-34, caused by IRE1α deficiency, play major roles in repressing PPARα and SIRT1 expression in hepatocytes. Considering the 3-UTR reporter assays (in Fig. 7, F and G) and miR antagomir results (in Fig. 8, A and B), miR-200 appears to be dominant over miR-34 in suppressing PPARα abundance, whereas miR-34 appears to be more dominant in suppressing SIRT1 abundance. The mechanism underlying this distinction is an interesting question to be elucidated with future work.

Fig. 8. Inhibition of miR-34 or miR-200 reduces hepatic steatosis caused by IRE1 deficiency.

(A) qPCR analysis of Pparα or Sirt1 mRNA abundance in OA-treated IRE1α KO and CTL hepatocytes transfected with scramble oligonucleotides (Scr), miR-34 antagomir (miR-34i) or miR-200 family antagomir (miR-200i). Data are means ± SEM (n=3 biological replicates. * p<0.05 vs. CTL+Scr. # p<0.05 vs. KO+Scr by unpaired 2-tailed Student’s T-Test. (B) Western blot analysis of PPARα and SIRT1 in OA-treated IRE1α KO and CTL hepatocytes transfected with Scr, miR-34i or miR-200i. GAPDH, loading control. Data are means ± SEM (n=3 biological replicates); * p<0.05. (C) Oil-red O staining of neutral lipids in OA-incubated IRE1α KO and CTL hepatocytes transfected with Scr, miR-34i, or miR-200i for 24 hours. Scale bar, 5μm. Data are means ± SEM (n=3 biological replicates). * p<0.05 vs. CTL + Scr; # p<0.05 vs. KO + Scr. (D) Oil-red O staining of neutral lipids in IRE1α KO hepatocytes and CTL over-expressing PPARα, SIRT1 or GFP, after incubation with OA for 24 hours. Scale bar, 5μm. Data are means ± SEM (n=3 biological replicates). * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 vs. CTL + GFP; # p<0.05 vs. KO + GFP. (E) Illustration of the IRE1α-miRNA pathway in hepatic steatosis.

Because IRE1α suppresses biogenesis of miR-200 and miR-34, we hypothesized that increased abundance of the miR-200 and miR-34 families and subsequent down-regulation of PPARα and SIRT1 may account for hepatic steatosis caused by IRE1α deficiency. To test this hypothesis, we first expressed miR-200 or miR-34 antagomir in Ire1α−/− and control hepatocytes incubated with OA or PA, and then examined lipid accumulation in the hepatocytes. Upon incubation with an miR-200 or miR-34 antagomir, lipid accumulation was significantly reduced in Ire1α−/− hepatocytes (Fig. 8C, fig. S8C). Furthermore, over-expression of PPARα or SIRT1 in Ire1α−/− hepatocytes reduced the accumulation of hepatic lipids and increased the expression of PPARα-target genes involved in fatty acid oxidation in oleic acid- or palmitate- treated Ire1α−/− hepatocytes (Fig. 8D, fig. S9), similar to the effect of the miR-200 and miR-34 antagomirs. Notably, exogenous expression of SIRT1 exhibited greater efficacy than expression of PPARα in relieving hepatic lipid accumulation in Ire1α−/− hepatocytes. This is consistent with the fact that SIRT1 functions as an upstream enhancer of PPARα in facilitating fatty acid oxidation and triglyceride lipolysis (29, 30).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated a physiological role for the primary UPR transducer IRE1α in maintaining energy homeostasis associated with chronic metabolic conditions, which is distinct from its canonical role in mediating the UPR (Fig 8E). IRE1α plays a crucial role in preventing hepatic steatosis by functioning as an RNase to process a subset of miRNAs that are involved in hepatic lipid metabolism. We found that IRE1α RNase processes select pre-miRNAs and thus prevents their maturation. Notably, our findings demonstrated that both splicing of Xbp1 mRNA and activity of XBP1s are defective in the livers of HFD-fed mice and in fat-loaded hepatocytes despite phosphorylation and sustained expression of IRE1α. Deficiency in IRE1α RNase activity, caused by HFD- or hepatic steatosis-induced S-nitrosylation of IRE1α, led to up-regulation of “metabolic” miRNAs. Subsequently, up-regulation of the miRNAs, particularly of the miR-34 and miR-200 families, down-regulates the key metabolic regulators SIRT1 and PPARα in the liver, thus promoting a NASH-like phenotype. Our findings from this study provide new insights into the physiological roles and molecular mechanisms of the UPR signaling in energy homeostasis and metabolic disorders.

It has been implicated that UPR signaling exhibits different patterns under physiological alterations associated with metabolic disease (3, 5, 6). Depending on acute or chronic pathophysiological conditions, the UPR transducer IRE1α may act as an RNase or a scaffold through its cytosolic domain to modulate inflammatory and/or metabolic stress signaling pathways (8, 15). It was previously reported that the IRE1α-XBP1 pathway was activated in the livers of NASH patients or animal models (32–34). However, our study showed that a HFD de-activated IRE1α RNase activity towards both Xbp1 mRNA splicing and select miRNA processing in the liver. This is consistent with studies in the literature reporting that the protective UPR pathway mediated through IRE1α is impaired in the livers of NASH patients or obese animal models (5, 6, 20, 35, 36). In particular, S-nitrosylation of IRE1α, induced by obesity and associated chronic inflammation, uncouples the kinase and RNase functions of IRE1α protein, and thus suppresses IRE1α RNase activity and Xbp1 mRNA splicing in the liver (20). Indeed, UPR signaling triggered by acute insults or pharmaceutical inducers, for example, tunicamycin and thapsigargin, differs from that activated under physiological alterations (37–39), as confirmed in this study. The stress condition in the liver in the HFD context was not comparable to that associated with advanced or terminal-stage NASH in which liver injuries, such as fibrosis and even cirrhosis, are prominent. Moreover, metabolic diets with nutrient restriction or supplemented with oxidants, such as the methionine and choline-deficient (MCD) diet and the atherogenic (Paigen) diet (40, 41), are associated with acute stress in the liver that may activate the canonical IRE1α-XBP1 UPR pathway. In contrast, simple HFD-induced chronic, pathophysiological conditions can lead to IRE1α nitrosylation and subsequent suppression of IRE1α RNase activity.

Although several studies characterized metabolic phenotypes of Ire1α-null mice under acute stress conditions, the current study delineated the phenotypes of conditional Ire1α-KO mice under a chronic, metabolic stress condition. Hepatic-specific Ire1α-KO mice developed profound NASH, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance after 20 weeks of HFD. These in vivo results are in line with our in vitro finding that Ire1α−/− hepatocytes are more susceptible to steatosis and lipotoxicity compared with the control hepatocytes. Our analysis indicated that, under prolonged HFD feeding, the IRE1α-XBP1 UPR branch was de-activated in the liver, and a subset of miRNAs that are targeted by IRE1α-RIDD pathway was increased. In particular, the expression of two major regulators in fatty acid oxidation and triglyceride lipolysis, the liver-enriched transcriptional activator PPARα and the deacetylase SIRT1 were down-regulated by miR-200 and miR-34 family members in the fat-loaded or Ire1α-KO mouse livers or hepatocytes.

In the attempt to define the effector molecules targeted by the IRE1α-RIDD pathway in preventing HFD-induced hepatic steatosis, we found that IRE1α regulates the abundance of PPARα and SIRT1 by degrading the miRNAs that target the mRNAs encoding these two factors. We also identified previously unknown targets of the IRE1α-mediated RIDD pathway, specifically the miR-200 and miR-34 families, which suppress the expression of PPARα and SIRT1. These add to a growing list of RNA cleavage substrates of the IRE1α RNase. We chose miR-200 and miR-34 for further analyses because these two miRNA families play important roles in stress-induced cell injury and metabolism (42–44). For several reasons, our findings suggest direct regulation of the miR-200 and miR-34 families by IRE1α through the RIDD pathway: (i) overexpression of IRE1α, but not XBP1, suppressed maturation of miR-200 and miR-34 family members; (ii) the abundances of pre- and mature miR-200 and miR-34, but not of pri-miR-200 and pri-miR-34, are increased in IRE1α-null hepatocytes, suggesting that IRE1α suppresses miRNA biogenesis at pre-miRNA level; (iii) expression of pre-miR-200 and pre-miR-34 in Ire1α−/− hepatocytes yielded significantly higher amounts of mature miR-200 and miR-34, compared to that in wild-type control cells; and (iv) in vitro cleavage assays demonstrated that the recombinant IRE1α protein can process pre-miR-200 and pre-miR-34, leading to their degradation. Thus, we conclude that processing and subsequent repression of miRNAs by IRE1α represents an important regulatory mechanism of metabolic homeostasis by the UPR – a regulatory activity that is distinct from the canonical UPR role in coping with ER stress.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless indicated otherwise. Synthetic oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA). Antibodies against ADRP, IRE1α, PPARα, SIRT1, acetylated lysine, PGC1α, and XBP1 were purchased from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA), Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA), Millipore Corp (Billerica, MA), Abcam (Cambridge, MA), Sigma (St. Louis, MO), Santa Cruz Biotech (Santa Cruz, CA), and BioLegend (San Diego, CA), respectively. S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) was from Sigma.

Mouse experiments

The Ire1αfl/fl mice were generated as we described previously (2, 45). The IRE1αfl/fl mice were backcrossed with C57BL/6J mice for over 10 generations to maintain the C57BL strain background. The hepatocyte-specific IRE1α knockout (KO) mice were generated by crossing Ire1αfl/fl mice with transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the albumin promoter (Alb-Cre). Alb-Cre transgenic mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories. Hepatocyte-specific Ire1α KO (Ire1−/−) mice and control mice (Ire1αfl/fl) at 3 months of age were used for the metabolic diet study. The HFD (45% kcal fat) was purchased from Research Diet, Inc (Cat#: D12451). The NC diet served as control diet. The animal experiments were approved by the Wayne State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were carried out under the institutional guidelines for ethical animal use.

Human liver samples

Human steatosis and non-steatosis control liver tissue samples were obtained from the Liver Tissue Cell Distribution System at the University of Minnesota. The human patients with hepatic steatosis were in the average age 47, HCV/HBV negative, and had no NASH or Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC). The human non-steatosis liver controls were in the average age 50, HCV/HBV negative, and had no NASH or HCC. The use of human liver tissues was approved by the IRB as none human subject research.

Measurement of mouse lipid contents

Levels of plasma triglyceride, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein, and low and very low density lipoprotein in the mice were determined enzymatically using commercial kits (Roche Diagnostics Corporation). To quantify hepatic triglyceride levels, approximately 50 mg mouse liver tissue was homogenized in 5% PBS followed by centrifugation. The supernatant was collected for TG measurement using a commercial kit (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA).

Histological scoring for NASH activities

Mouse paraffin-embedded liver tissue sections (5μm) were subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining, ADRP immunohistochemical staining, or Sirius-red staining. The histological analysis of HE-stained and Sirius-red-stained tissue sections for liver inflammation and fibrosis. Hepatic steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, lobular and portal inflammation, Mallory bodies, and fibrosis were examined and scored according to the modified Brunt scoring system for NAFLD (46, 47). The grade scores were calculated based on the scores of steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, lobular and portal inflammation, and Mallory bodies. Hepatic fibrosis was evaluated by Sirius-red staining. Each section was examined by a specialist who was blinded to the sample information. Hepatic fibrosis were scored according to the modified Scheuer scoring system for fibrosis and cirrhosis (0–4 stage): 0, none; 1, zone 3 perisinusoidal fibrosis; 2, zone 3 perisinusoidal fibrosis plus portal fibrosis; 3, perisinusoidal fibrosis, portal fibrosis, plus bridging fibrosis; and 4, cirrhosis.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR analysis (qPCR)

Total RNA from mouse liver tissues or cultured hepatocytes were isolated by miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). For mRNA expression, cDNA was generated from 200 ng of RNA using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies). qPCR was performed using SYBR green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). For miRNA detections, cDNA was generated from 10 ng of small RNAs using a miRCURY LNA cDNA Synthesis kit (Exiqon). qPCR was performed using miR primers synthesized by Exiqon. For pre-miRNA qPCRs, cDNA was generated using a miScript II Reverse Transcription (RT) Kit (Qiagen). qPCR was performed using a miScript Precursor Assay kit (Qiagen). For pri-miR qPCRs, cDNA was generated from 500ng of RNA using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies). qPCR was performed using a TaqMan Pri-miRNA Assay kit (Life Technologies). Amplification and detection of specific products were performed with an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR Systems, using U6 as an internal control for miRNA detection.

Western blot analysis

Total cellular protein lysates were prepared from cultured cells or mouse liver tissue using NP-40 lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (EDTA-free Complete Mini, Roche). Denatured proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membranes (GE Healthcare). For the detection of phosphorylated IRE1α, 30 μg of cellular lysates were loaded in 5% Phos-tag SDS-PAGE gel (Wako Chemicals) and ran according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The membranes was incubated with a rabbit or mouse primary antibody and a HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Membrane-bound antibodies were detected by a chemiluminescence detection reagent (GE Healthcare). The signal intensities were determined by Quantity One 4.4.0 (Bio-Rad Life Science, CA).

Generation of IRE1α−/− hepatocyte cell lines and adenoviral infection

Primary murine hepatocytes were isolated from mice harboring floxed homozygous Ire1α alleles and immortalized by SV40 T antigen. Immortalized hepatocytes were treated with adenovirus-Cre in order to delete the floxed Ire1α exons as we described previously (2). Recombinant adenovirus expressing flag-tagged human IRE1α (Ad-IRE1α) was kindly provided by Dr. Yong Liu (Institute for Nutritional Sciences, Shanghai, China). Adenovirus expressing spliced XBP1 was kindly provided by Dr. Umut Ozcan (Harvard University). Hepatocytes were infected with Ad-IRE1α, Ad-XBP1s or Ad-GFP at MOI of 100 for 48 hours before the sample collection.

Transfection of Pre-miRNA expressing plasmids

Plasmids expressing pre-miR-200 or pre-miR-34 were constructed by inserting human pre-miR-200 sequence (CCAGCUCGGGCAGCCGUGGCCAUCUUA CUGGGCAGCAUUGGAUGGAGUCAGGUCUCUAAUACUGCCUGGUAAUGAUGACGGCGGAGCCCUGCACG) or human pre-miR-34 sequence (GGCCAGCUGUGAGUGUUUCUUUGGCAGUGUCUUAGC UGGUUGUUGUGAGCAAUAGUAAGGAAGCAAUCAGCAAGUAUACUGCCCUAGAAGUGCUGCACG UUGUGGGGCCC) into pCMV-miR vector between SgfI and MluI site. The empty plasmid served as the control. Cells were transfected with either 100ng of pre-miR-expressing plasmid or empty plasmid. Samples were collected simultaneously 24 h after transfection for RNA analysis.

In vitro IRE1α-mediated pre-miR cleavage assays

In vitro cleavage of pre-miR-200 and pre-miR-34 by recombinant, bio-active IRE1α protein was carried out as described previously with modifications (17). Briefly, pre-miR-200 and pre-miR-34 were amplified by PCR using plasmids carrying either human pre-miR-200 or pre-miR-34 sequence as template and primers provided by the manufacture. Transcription of large-scale RNAs of pre-miR-200 or pre-miR-34 was performed using T7 RiboMaxTM Express RNA Production system (Promega). Approximately 1μg in vitro-transcribed miRNAs were incubate with 1μg bio-active recombinant human IRE1α protein (aa468-end, purchased from SignalChem, Inc) in a buffer containing 25mM MOPS, pH7.2, 12.5 mM β-glycerol-phosphate, 25mM MgCl2, 5mM EGTA, and 2mM EDTA. The cleavage reactions were initiated by adding ATP (2mM). Reaction without ATP was included as the control for each sample. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, the reaction products were resolved on a 1.2% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

3′-UTR luciferase activity assays

Synthetic oligonucleotides of human PPARα or SIRT1 mRNA 3′UTR was cloned into a luciferase reporter vector system (SwitchGear). HEK 293T cells were co-transfected with 100ng of PPARα or SIRT1 3′-UTR reporter and 0.1nmol of miR mimics (Exiqon) or 100ng of pre-miR plasmids using DharmaFECT Duo transfection reagent (Dharmacon) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After 48 h, luciferase activity was measured. A reduced firefly luciferase expression indicates the direct binding of miRs to the cloned target sequence.

Biotin switch assay

Biotin switch-Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (20, 48). Biotinylated proteins were pulled down using NanoLink™ Streptavidin Magnetic Beads (Solulink), and the IRE1α protein was examined using a rabbit anti-IRE1α antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). In situ detection of S-nitrosylated proteins was performed as previously described (49, 50). Free thiols in liver tissue sections were first blocked using HENS buffer (2 % SDS) containing 20 mM MMTS. Biotinylated proteins were labelled using streptavidin conjugated with Alexa-488. The liver tissue sections were then subject to immunostaining for IRE1α using the IRE1α antibody and an anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa-568. The images were observed by using Ziess 700 confocal microscopy. Colocalizations of S-nitrosylated IRE1α were quantified using ImarisColoc software (Bitplane) and analyzed for Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

Electrophoretic analysis of Xbp1 splicing

Total RNAs isolated from mouse liver tissues or cultured hepatocytes were subjected to semi-quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR using the following primers to amplify a 451bp un-spliced Xbp1 fragment or a 425bp spliced Xbp1 fragment: 5′-CCTTGTGGTTGAGAACCAGG-3′ and 5′-CTAGAGGCTTGGTGTATAC-3′. To distinct the spliced from un-spliced Xbp1 transcripts, PCR products were subjected to PstI restriction enzyme digestion, which only cleaves the intron included in the un-spliced Xbp1 cDNA to give a 154bp and a 297bp fragment, leaving the spliced Xbp1 cDNA intact (26). β-actin transcript was also amplified by semi-quantitative RT-PCR as internal control. The PstI-digested products were analyzed by 2% agarose gel, and the Xbp1 signals were quantified by NIH ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

Experimental results are shown as mean ± SEM (for variation between animals or experiments). The mean values for biochemical data from the experimental groups were compared by a paired or unpaired, 2-tailed Student’s t test. When more than two treatment groups were compared, one-way ANOVA followed by LSD post hoc testing was used. Statistical tests with P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. R. Hassler for his critical comments on this manuscript and R. Pique-Regi for his validation of the statistical tests used in this study.

Funding: Portions of this work were supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants DK090313 and ES017829 (to KZ), AR066634 (to KZ and DF), DK042394 and DK103185 (to RJK), DK109036 (to JW), and 1R01DK108835-01A1 (to L. Yang); and American Heart Association grants 0635423Z and 09GRNT2280479 (to KZ).

Footnotes

Fig S1. Metabolic phenotype of IRE1α KO and CTL mice fed NC or a HFD.

Fig S2. Immunofluorescent staining of IRE1α and S-nitrosylation (SNO) signals in mouse liver tissues.

Fig S3. miRNA profiles in IRE1α KO and CTL livers from NC- or HFD-fed mice and in oleic acid-loaded mouse hepatocytes.

Fig S4. Palmitate represses IRE1α activity in processing select miRNAs.

Fig S5. Titration and duration analyses for the effect of XBP1 overexpression on modulating miR-200 and miR-34.

Fig S6. Expression of the genes involved in lipid and glucose metabolism in IRE1α KO and CTL mice fed NC or a HFD.

Fig S7. miRNA-binding sequences of miR-200 and miR-34 family members in the 3-UTRs of human PPARα and SIRT1 genes.

Fig S8. Inhibition of miR-34 or miR-200 rescues Pparα and Sirt1 expression and reduces hepatic steatosis caused by IRE1 deficiency with palmitate treatment.

Fig S9. Over-expression of PPARα or SIRT1 reduces hepatic steatosis caused by IRE1 deficiency with palmitate treatment.

Table S1. miRNA functional clusters and previously identified targets.

Author contributions: K.Z., J.W., and L. Yang designed and conducted the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; Y.Q., Z.Y., H.K., Q.Q., C.Z., and S.H.B. performed the experiments and acquired the data; Q.S., L. Yin, D.F., and R.J.K. provided key reagents and critical comments.

Competing interests: All authors declare they have no any financial, professional, or personal conflicts related to this work.

References and Notes

- 1.Pagliassotti MJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Annual review of nutrition. 2012;32:17–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071811-150644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang K, Wang S, Malhotra J, Hassler JR, Back SH, Wang G, Chang L, Xu W, Miao H, Leonardi R, Chen YE, Jackowski S, Kaufman RJ. The unfolded protein response transducer IRE1alpha prevents ER stress-induced hepatic steatosis. The EMBO journal. 2011;30:1357–1375. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. From endoplasmic-reticulum stress to the inflammatory response. Nature. 2008;454:455–462. doi: 10.1038/nature07203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fu S, Watkins SM, Hotamisligil GS. The role of endoplasmic reticulum in hepatic lipid homeostasis and stress signaling. Cell metabolism. 2012;15:623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell. 2010;140:900–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang M, Kaufman RJ. Protein misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum as a conduit to human disease. Nature. 2016;529:326–335. doi: 10.1038/nature17041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hummasti S, Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and inflammation in obesity and diabetes. Circ Res. 2010;107:579–591. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.225698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollien J, Weissman JS. Decay of endoplasmic reticulum-localized mRNAs during the unfolded protein response. Science. 2006;313:104–107. doi: 10.1126/science.1129631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Upton JP, Wang L, Han D, Wang ES, Huskey NE, Lim L, Truitt M, McManus MT, Ruggero D, Goga A, Papa FR, Oakes SA. IRE1alpha cleaves select microRNAs during ER stress to derepress translation of proapoptotic Caspase-2. Science. 2012;338:818–822. doi: 10.1126/science.1226191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollien J, Lin JH, Li H, Stevens N, Walter P, Weissman JS. Regulated Ire1-dependent decay of messenger RNAs in mammalian cells. The Journal of cell biology. 2009;186:323–331. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin JH, Li H, Yasumura D, Cohen HR, Zhang C, Panning B, Shokat KM, Lavail MM, Walter P. IRE1 signaling affects cell fate during the unfolded protein response. Science. 2007;318:944–949. doi: 10.1126/science.1146361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tam AB, Koong AC, Niwa M. Ire1 has distinct catalytic mechanisms for XBP1/HAC1 splicing and RIDD. Cell Rep. 2014;9:850–858. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peschek J, Acosta-Alvear D, Mendez AS, Walter P. A conformational RNA zipper promotes intron ejection during non-conventional XBP1 mRNA splicing. EMBO reports. 2015;16:1688–1698. doi: 10.15252/embr.201540955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urano F, Wang X, Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Chung P, Harding HP, Ron D. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science. 2000;287:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang S, Chen Z, Lam V, Han J, Hassler J, Finck BN, Davidson NO, Kaufman RJ. IRE1alpha-XBP1s induces PDI expression to increase MTP activity for hepatic VLDL assembly and lipid homeostasis. Cell metabolism. 2012;16:473–486. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.So JS, Hur KY, Tarrio M, Ruda V, Frank-Kamenetsky M, Fitzgerald K, Koteliansky V, Lichtman AH, Iwawaki T, Glimcher LH, Lee AH. Silencing of lipid metabolism genes through IRE1alpha-mediated mRNA decay lowers plasma lipids in mice. Cell metabolism. 2012;16:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrema H, Zhou Y, Zhang D, Lee J, Salazar Hernandez MA, Shulman GI, Ozcan U. XBP1s is an antilipogenic protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2016;291:17394–17404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.728949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X, Henkel AS, LeCuyer BE, Schipma MJ, Anderson KA, Green RM. Hepatocyte X-box binding protein 1 deficiency increases liver injury in mice fed a high-fat/sugar diet. American journal of physiology Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2015;309:G965–974. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00132.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang L, Calay ES, Fan J, Arduini A, Kunz RC, Gygi SP, Yalcin A, Fu S, Hotamisligil GS. METABOLISM. S-Nitrosylation links obesity-associated inflammation to endoplasmic reticulum dysfunction. Science. 2015;349:500–506. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Rooij E, Olson EN. MicroRNAs: powerful new regulators of heart disease and provocative therapeutic targets. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2369–2376. doi: 10.1172/JCI33099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuehbacher A, Urbich C, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Role of Dicer and Drosha for endothelial microRNA expression and angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2007;101:59–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang JM, Qiu Y, Yang ZQ, Li L, Zhang K. Inositol-Requiring Enzyme 1 Facilitates Diabetic Wound Healing Through Modulating MicroRNAs. Diabetes. 2017;66:177–192. doi: 10.2337/db16-0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang L, Xue Z, He Y, Sun S, Chen H, Qi L. A Phos-tag-based approach reveals the extent of physiological endoplasmic reticulum stress. PloS one. 2010;5:e11621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 2001;107:881–891. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uehara T, Nakamura T, Yao D, Shi ZQ, Gu Z, Ma Y, Masliah E, Nomura Y, Lipton SA. S-nitrosylated protein-disulphide isomerase links protein misfolding to neurodegeneration. Nature. 2006;441:513–517. doi: 10.1038/nature04782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moravcova A, Cervinkova Z, Kucera O, Mezera V, Rychtrmoc D, Lotkova H. The effect of oleic and palmitic acid on induction of steatosis and cytotoxicity on rat hepatocytes in primary culture. Physiological research. 2015;64(Suppl 5):S627–636. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.933224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang HC, Guarente L. SIRT1 and other sirtuins in metabolism. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM. 2014;25:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Purushotham A, Schug TT, Xu Q, Surapureddi S, Guo X, Li X. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of SIRT1 alters fatty acid metabolism and results in hepatic steatosis and inflammation. Cell metabolism. 2009;9:327–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeninga EH, Schoonjans K, Auwerx J. Reversible acetylation of PGC-1: connecting energy sensors and effectors to guarantee metabolic flexibility. Oncogene. 2010;29:4617–4624. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed U, Redgrave TG, Oates PS. Effect of dietary fat to produce non-alcoholic fatty liver in the rat. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2009;24:1463–1471. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang S, Yan C, Fang QC, Shao ML, Zhang YL, Liu Y, Deng YP, Shan B, Liu JQ, Li HT, Yang L, Zhou J, Dai Z, Liu Y, Jia WP. Fibroblast growth factor 21 is regulated by the IRE1alpha-XBP1 branch of the unfolded protein response and counteracts endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced hepatic steatosis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2014;289:29751–29765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.565960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lake AD, Novak P, Hardwick RN, Flores-Keown B, Zhao F, Klimecki WT, Cherrington NJ. The adaptive endoplasmic reticulum stress response to lipotoxicity in progressive human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Toxicological sciences. 2014;137:26–35. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puri P, Mirshahi F, Cheung O, Natarajan R, Maher JW, Kellum JM, Sanyal AJ. Activation and dysregulation of the unfolded protein response in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:568–576. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lipson KL, Fonseca SG, Ishigaki S, Nguyen LX, Foss E, Bortell R, Rossini AA, Urano F. Regulation of insulin biosynthesis in pancreatic beta cells by an endoplasmic reticulum-resident protein kinase IRE1. Cell metabolism. 2006;4:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hetz C. The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2012;13:89–102. doi: 10.1038/nrm3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DuRose JB, Tam AB, Niwa M. Intrinsic capacities of molecular sensors of the unfolded protein response to sense alternate forms of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Molecular biology of the cell. 2006;17:3095–3107. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-01-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee JS, Zheng Z, Mendez R, Ha SW, Xie Y, Zhang K. Pharmacologic ER stress induces non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in an animal model. Toxicol Lett. 2012;211:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weltman MD, Farrell GC, Liddle C. Increased hepatocyte CYP2E1 expression in a rat nutritional model of hepatic steatosis with inflammation. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1645–1653. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paigen B, Morrow A, Holmes PA, Mitchell D, Williams RA. Quantitative assessment of atherosclerotic lesions in mice. Atherosclerosis. 1987;68:231–240. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(87)90202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mateescu B, Batista L, Cardon M, Gruosso T, de Feraudy Y, Mariani O, Nicolas A, Meyniel JP, Cottu P, Sastre-Garau X, Mechta-Grigoriou F. miR-141 and miR-200a act on ovarian tumorigenesis by controlling oxidative stress response. Nature medicine. 2011;17:1627–1635. doi: 10.1038/nm.2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cufi S, Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Quirantes R, Segura-Carretero A, Micol V, Joven J, Bosch-Barrera J, Del Barco S, Martin-Castillo B, Vellon L, Menendez JA. Metformin lowers the threshold for stress-induced senescence: a role for the microRNA-200 family and miR-205. Cell cycle. 2012;11:1235–1246. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.6.19665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rippo MR, Olivieri F, Monsurro V, Prattichizzo F, Albertini MC, Procopio AD. MitomiRs in human inflamm-aging: a hypothesis involving miR-181a, miR-34a and miR-146a. Experimental gerontology. 2014;56:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qiu Q, Zheng Z, Chang L, Zhao YS, Tan C, Dandekar A, Zhang Z, Lin Z, Gui M, Li X, Zhang T, Kong Q, Li H, Chen S, Chen A, Kaufman RJ, Yang WL, Lin HK, Zhang D, Perlman H, Thorp E, Zhang K, Fang D. Toll-like receptor-mediated IRE1alpha activation as a therapeutic target for inflammatory arthritis. The EMBO journal. 2013;32:2477–2490. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brunt EM, Janney CG, Di Bisceglie AM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Bacon BR. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2467–2474. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brunt EM. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: definition and pathology. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:3–16. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Derakhshan B, Wille PC, Gross SS. Unbiased identification of cysteine S-nitrosylation sites on proteins. Nature protocols. 2007;2:1685–1691. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thibeault S, Rautureau Y, Oubaha M, Faubert D, Wilkes BC, Delisle C, Gratton JP. S-nitrosylation of beta-catenin by eNOS-derived NO promotes VEGF-induced endothelial cell permeability. Molecular cell. 2010;39:468–476. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qian Q, Zhang Z, Orwig A, Chen S, Ding WX, Xu Y, Kunz RC, Lind NRL, Stamler JS, Yang L. S-Nitrosoglutathione Reductase Dysfunction Contributes to Obesity-Associated Hepatic Insulin Resistance via Regulating Autophagy. Diabetes. 2018;67:193–207. doi: 10.2337/db17-0223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen X, Ling Y, Wei Y, Tang J, Ren Y, Zhang B, Jiang F, Li H, Wang R, Wen W, Lv G, Wu M, Chen L, Li L, Wang H. Dual regulation of HMGB1 by combined JNK1/2-ATF2 axis with miR-200 family in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. FASEB J. 2018 doi: 10.1096/fj.201700875R. fj201700875R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoneyama K, Ishibashi O, Kawase R, Kurose K, Takeshita T. miR-200a, miR-200b and miR-429 are onco-miRs that target the PTEN gene in endometrioid endometrial carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:1401–1410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Werner TV, Hart M, Nickels R, Kim YJ, Menger MD, Bohle RM, Keller A, Ludwig N, Meese E. MiR-34a-3p alters proliferation and apoptosis of meningioma cells in vitro and is directly targeting SMAD4, FRAT1 and BCL2. Aging (Albany NY) 2017;9:932–954. doi: 10.18632/aging.101201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Si W, Li Y, Shao H, Hu R, Wang W, Zhang K, Yang Q. MiR-34a Inhibits Breast Cancer Proliferation and Progression by Targeting Wnt1 in Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Am J Med Sci. 2016;352:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Santis R, Liepelt A, Mossanen JC, Dueck A, Simons N, Mohs A, Trautwein C, Meister G, Marx G, Ostareck-Lederer A, Ostareck DH. miR-155 targets Caspase-3 mRNA in activated macrophages. RNA Biol. 2016;13:43–58. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1109768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang B, Majumder S, Nuovo G, Kutay H, Volinia S, Patel T, Schmittgen TD, Croce C, Ghoshal K, Jacob ST. Role of microRNA-155 at early stages of hepatocarcinogenesis induced by choline-deficient and amino acid-defined diet in C57BL/6 mice. Hepatology. 2009;50:1152–1161. doi: 10.1002/hep.23100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Du J, Niu X, Wang Y, Kong L, Wang R, Zhang Y, Zhao S, Nan Y. MiR-146a-5p suppresses activation and proliferation of hepatic stellate cells in nonalcoholic fibrosing steatohepatitis through directly targeting Wnt1 and Wnt5a. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16163. doi: 10.1038/srep16163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu HY, Bai WD, Liu JQ, Zheng Z, Guan H, Zhou Q, Su LL, Xie ST, Wang YC, Li J, Li N, Zhang YJ, Wang HT, Hu DH. Up-regulation of FGFBP1 signaling contributes to miR-146a-induced angiogenesis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25272. doi: 10.1038/srep25272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dong Z, Qi R, Guo X, Zhao X, Li Y, Zeng Z, Bai W, Chang X, Hao L, Chen Y, Lou M, Li Z, Lu Y. MiR-223 modulates hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation through promoting apoptosis via the Rab1-mediated mTOR activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;483:630–637. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.12.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schueller F, Roy S, Loosen SH, Alder J, Koppe C, Schneider AT, Wandrer F, Bantel H, Vucur M, Mi QS, Trautwein C, Luedde T, Roderburg C. miR-223 represents a biomarker in acute and chronic liver injury. Clin Sci (Lond) 2017;131:1971–1987. doi: 10.1042/CS20170218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maegdefessel L, Spin JM, Raaz U, Eken SM, Toh R, Azuma J, Adam M, Nakagami F, Heymann HM, Chernogubova E, Jin H, Roy J, Hultgren R, Caidahl K, Schrepfer S, Hamsten A, Eriksson P, McConnell MV, Dalman RL, Tsao PS. miR-24 limits aortic vascular inflammation and murine abdominal aneurysm development. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5214. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ye SB, Zhang H, Cai TT, Liu YN, Ni JJ, He J, Peng JY, Chen QY, Mo HY, Jun C, Zhang XS, Zeng YX, Li J. Exosomal miR-24-3p impedes T-cell function by targeting FGF11 and serves as a potential prognostic biomarker for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Pathol. 2016;240:329–340. doi: 10.1002/path.4781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rice MA, Ishteiwy RA, Magani F, Udayakumar T, Reiner T, Yates TJ, Miller P, Perez-Stable C, Rai P, Verdun R, Dykxhoorn DM, Burnstein KL. The microRNA-23b/-27b cluster suppresses prostate cancer metastasis via Huntingtin-interacting protein 1-related. Oncogene. 2016;35:4752–4761. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang JY, Li XF, Li PZ, Zhang X, Xu Y, Jin X. MicroRNA-23b regulates nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell proliferation and metastasis by targeting E-cadherin. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14:537–543. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang JM, Isenberg JS, Billiar TR, Chen AF. Thrombospondin-1/CD36 pathway contributes to bone marrow-derived angiogenic cell dysfunction in type 1 diabetes via Sonic hedgehog pathway suppression. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305:E1464–E1472. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00516.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu XM, Wang XB, Chen MM, Liu T, Li YX, Jia WH, Liu M, Li X, Tang H. MicroRNA-19a and -19b regulate cervical carcinoma cell proliferation and invasion by targeting CUL5. Cancer Lett. 2012;322:148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou J, Wang KC, Wu W, Subramaniam S, Shyy JY, Chiu JJ, Li JY, Chien S. MicroRNA-21 targets peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor-alpha in an autoregulatory loop to modulate flow-induced endothelial inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:10355–10360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107052108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kida K, Nakajima M, Mohri T, Oda Y, Takagi S, Fukami T, Yokoi T. PPARalpha is regulated by miR-21 and miR-27b in human liver. Pharm Res. 2011;28:2467–2476. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0473-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jacobs ME, Kathpalia PP, Chen Y, Thomas SV, Noonan EJ, Pao AC. SGK1 regulation by miR-466g in cortical collecting duct cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;310:F1251–1257. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00024.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Colden M, Dar AA, Saini S, Dahiya PV, Shahryari V, Yamamura S, Tanaka Y, Stein G, Dahiya R, Majid S. MicroRNA-466 inhibits tumor growth and bone metastasis in prostate cancer by direct regulation of osteogenic transcription factor RUNX2. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2572. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.