Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common childhood malignancy. This report describes the survival of children with ALL in the United States using the most comprehensive and up-to-date cancer registry data.

METHODS:

Data from 37 state cancer registries that cover approximately 80% of the US population were used. Age-standardized survival up to 5 years was estimated for children aged 0–14 years who were diagnosed with ALL during 2 periods (2001–2003 and 2004–2009).

RESULTS:

In total, 17,500 children with ALL were included. The pooled age-standardized net survival estimates for all US registries combined were 95% at 1 year, 90% at 3 years, and 86% at 5 years for children diagnosed during 2001–2003, and 96%, 91%, and 88%, respectively, for those diagnosed during 2004–2009. Black children who were diagnosed during 2001–2003 had lower 5-year survival (84%) than white children (87%) and had less improvement in survival by 2004–2009. For those diagnosed during 2004–2009, the 1-year and 5- year survival estimates were 96% and 89%, respectively, for white children and 96% and 84%, respectively, for black children. During 2004–2009, survival was highest among children aged 1 to 4 years (95%) and lowest among children aged <1 year (60%).

CONCLUSIONS:

The current results indicate that overall net survival from childhood ALL in the United States is high, but disparities by race still exist, especially beyond the first year after diagnosis. Clinical and public health strategies are needed to improve health care access, clinical trial enrollment, treatment, and survivorship care for children with ALL.

Keywords: acute lymphoblastic leukemia, childhood cancer, childhood leukemia, leukemia, population-based cancer survival

INTRODUCTION

One of the great successes in medicine in the United States has been the increasing survival of children with cancer. In the past 50 years, 5-year survival from all cancers combined among children in the United States has increased from <60% to nearly 80%.1 Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common childhood malignancy worldwide, accounting for 20% to 30% of overall childhood cancer incidence.2–5 Before 1950, childhood ALL was uniformly fatal.6 In the 1960s, 5- year survival for children with ALL in the United States was <10%.7,8 Since then, 5-year survival has dramatically improved, from 57% between 1975 and 1979 to 90% between 2003 and 2009.2,9 This increase in survival is consistent with stable incidence rates and decreasing mortality rates.10–12

The progress made in childhood ALL survival in developed countries over the past 4 decades largely stems from clinical and public health-related cancer control efforts. These include increasing clinical trial enrollment, improved supportive care, and risk-directed therapy that optimizes the efficacy of existing antileukemic agents.1,13–16 Pediatric cancer collaborative treatment groups, which have reported enrollment of over two-thirds of patients with childhood ALL over the past 2 decades, have designed randomized clinical trials that used risk-adaptive algorithms to adjust the intensity of treatment based on factors such as ALL subtype and chromosomal changes, age and white blood-cell count on diagnosis, presence of disease in the central nervous system, and persistence of residual disease during treatment.8,13,17–19 In addition to improving relapse-free and overall survival, a risk-based approach has allowed clinicians to reduce toxicities that contribute to late complications and mortality.17

Clinical trials and ensuing advances in risk-based therapy have contributed to the remarkable progress in improving clinical outcomes in the United States and other countries.13,14,20 This success lies in contrast to 5- year survival below 40% in many developing countries, which largely result from abandonment of therapy and high treatment-related mortality.21–23 Five-year net survival among children diagnosed with ALL previously was estimated at 85% or above in the United States, whereas it was still below 50% in several less wealthy countries participating in the worldwide cancer survival comparison of the CONCORD-2 study.2,9 That study established worldwide surveillance of cancer survival in 67 countries using data from over 25 million individuals diagnosed with cancer from 279 cancer registries.9 The current report builds on the CONCORD-2 study and describes the survival of children with ALL in the United States using the most comprehensive and up-to-date cancer registry data available by race and age.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used data from 37 state-wide cancer registries funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Cancer Institute that participated in the CONCORD-2 study, covering approximately 80% of the US population, and consented to inclusion of their data in the more detailed analyses reported here.9,24,25 We analyzed individual records for 17,500 children (ages 0–14 years) who were diagnosed with precursor-cell ALL (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition26 morphology codes 9727–9729 and 9835–9837) during 2001 through 2009 and were followed until December 31, 2009. We included all children with ALL in the analyses, even if the child had had a previous malignancy. In the extremely rare instance that a child was diagnosed with ALL on 2 or more occasions during 2001 through 2009, only the first occurrence was considered in the survival analyses.

We estimated net survival up to 5 years, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), for children diagnosed during 2001 through 2003 and 2004 through 2009 by race and state. We used the Pohar Perme estimator27 of net survival. Net survival can be interpreted as the probability of survival up to a given time since diagnosis after controlling for other causes of death (background mortality). To control for differences in background mortality between participating states by race and over time, we constructed life tables of all-cause mortality in the general population for each state from the number of deaths and the population, by single year of age, sex, calendar year, and, where possible, by race (black, white), using a flexible Poisson model.28 The life tables have been published.29

Children were grouped by diagnosis year into 2 calendar periods (2001–2003 and 2004–2009) to reflect changes in the methods used by US cancer registries to collect data on stage at diagnosis. From 2001 through 2003, most registries coded stage directly from medical records to Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Summary Stage 2000.10 Since 2004, all registries have derived Summary Stage 2000 using the Collaborative Staging System.11

We estimated net survival using the cohort approach for patients diagnosed during 2001 through 2003, because all patients had been followed for at least 5 years by December 31, 2009. We used the complete approach to estimate 5-year net survival for patients diagnosed during 2004 through 2009, because 5 years of follow-up data were not available for all patients. Net survival was estimated for 4 age groups (ages <1 year and 1–4, 5–9, and 10–14 years). We obtained age-standardized estimates by assigning equal weights to 3 age-specific estimates (0–4, 5–9, and 10–14 years).30 If 2 of the 3 age-specific estimates could not be obtained, then we present only the pooled, unstandardized survival estimate for all age groups combined (ages 0–14 years). Unstandardized estimates are italicized in Supporting Table 1. To explore variation with age in more detail, the first age group was split into 2 subgroups (Table 1). Trends, geographic variations, and differences in survival by race are presented graphically in bar charts and funnel plots.31 More details on data and methods are provided in the accompanying article by Allemani et al.32

Table 1.

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Net Survival (%) at 1, 3, and 5 Years After Diagnosis for Children (0–14 Years) Diagnosed During 2001 Through 2009 by Age, Race, Sex, and Calendar Period of Diagnosis: United States

| Age (years) | Year | All Children |

White |

Black |

Boys |

Girls |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS (%) | 95% CI | NS (%) | 95% CI | NS (%) | 95% CI | NS (%) | 95% CI | NS (%) | 95% CI | ||

| 2001–2003 | |||||||||||

| All agesa | 1 | 95.3 | 94.6–95.9 | 95.3 | 94.6–96.0 | 95.0 | 93.0–97.1 | 95.2 | 94.3–96.1 | 95.4 | 94.5–96.4 |

| 3 | 89.7 | 88.8–90.7 | 89.8 | 88.8–90.9 | 87.5 | 84.3–90.6 | 89.1 | 87.8–90.4 | 90.5 | 89.1–91.9 | |

| 5 | 86.4 | 85.3–87.4 | 86.6 | 85.5–87.7 | 83.8 | 80.3–87.3 | 85.4 | 83.9–86.8 | 87.7 | 86.1–89.2 | |

| <1 | 1 | 76.8 | 70.7–83.0 | 76.7 | 70.1–83.4 | 55.0 | 27.2–82.8 | 73.1 | 63.1–83.0 | 79.6 | 71.9–87.3 |

| 3 | 63.3 | 56.2–70.3 | 64.1 | 56.6–71.6 | 46.0 | 18.3–73.8 | 60.2 | 49.2–71.1 | 65.5 | 56.4–74.6 | |

| 5 | 60.5 | 53.4–67.6 | 60.9 | 53.2–68.6 | 46.0 | 18.3–73.8 | 56.3 | 45.2–67.4 | 63.6 | 54.4–72.8 | |

| 1–4 | 1 | 97.9 | 97.4–98.5 | 97.9 | 97.3–98.5 | 98.4 | 96.5–100.0 | 98.3 | 97.7–99.0 | 97.5 | 96.6–98.4 |

| 3 | 94.9 | 94.0–95.7 | 94.8 | 93.9–95.7 | 94.5 | 91.0–97.9 | 94.6 | 93.5–95.8 | 95.2 | 93.9–96.4 | |

| 5 | 92.5 | 91.5–93.5 | 92.3 | 91.2–93.4 | 93.3 | 89.6–97.1 | 92.3 | 90.9–93.6 | 92.8 | 91.3–94.3 | |

| 5–9 | 1 | 96.4 | 95.5–97.4 | 96.6 | 95.6–97.6 | 96.1 | 92.8–99.5 | 96.1 | 94.7–97.4 | 96.8 | 95.6–98.1 |

| 3 | 92.3 | 91.0–93.6 | 92.6 | 91.1–94.0 | 89.2 | 83.9–94.6 | 91.3 | 89.4–93.2 | 93.4 | 91.6–95.2 | |

| 5 | 89.2 | 87.7–90.8 | 89.7 | 88.0–91.4 | 86.1 | 80.2–92.1 | 87.7 | 85.5–90.0 | 90.9 | 88.8–93.0 | |

| 10–14 | 1 | 92.8 | 91.3–94.4 | 92.9 | 91.1–94.6 | 93.1 | 88.8–97.5 | 92.4 | 90.2–94.5 | 93.5 | 91.1–95.8 |

| 3 | 84.0 | 81.8–86.3 | 84.1 | 81.6–86.6 | 81.7 | 75.0–88.3 | 83.1 | 80.1–86.1 | 85.3 | 82.0–88.7 | |

| 5 | 79.4 | 76.9–81.9 | 79.8 | 77.1–82.5 | 74.7 | 67.2–82.2 | 77.9 | 74.5–81.2 | 81.6 | 77.9–85.3 | |

| 2004–2009 | |||||||||||

| All agesa | 1 | 95.7 | 95.3–96.1 | 95.7 | 95.3–96.2 | 95.5 | 94.1–96.9 | 95.9 | 95.3–96.4 | 95.5 | 94.8–96.2 |

| 3 | 90.7 | 90.0–91.4 | 91.2 | 90.5–92.0 | 86.7 | 84.2–89.1 | 90.2 | 89.3–91.2 | 91.3 | 90.2–92.3 | |

| 5 | 88.1 | 87.2–88.9 | 88.6 | 87.6–89.5 | 83.6 | 80.6–86.6 | 87.4 | 86.2–88.6 | 88.9 | 87.6–90.2 | |

| <1 | 1 | 80.5 | 76.4–84.6 | 78.0 | 73.2–82.8 | 94.9 | 88.7–100.0 | 78.5 | 72.6–84.3 | 82.8 | 77.1–88.4 |

| 3 | 61.7 | 56.2–67.1 | 59.7 | 53.5–65.8 | 73.6 | 60.3–87.0 | 56.7 | 49.2–64.2 | 67.7 | 60.1–75.3 | |

| 5 | 60.1 | 54.5–65.7 | 58.5 | 52.3–64.8 | 69.1 | 54.0–84.2 | 54.7 | 46.9–62.5 | 66.7 | 58.8–74.5 | |

| 1–4 | 1 | 98.4 | 98.0–98.7 | 98.3 | 98.0–98.7 | 98.6 | 97.5–99.8 | 98.3 | 97.8–98.8 | 98.5 | 98.0–99.0 |

| 3 | 96.1 | 95.5–96.7 | 96.2 | 95.6–96.8 | 93.6 | 90.8–96.3 | 95.8 | 95.0–96.6 | 96.5 | 95.6–97.3 | |

| 5 | 94.5 | 93.7–95.3 | 94.7 | 93.8–95.6 | 89.8 | 85.8–93.8 | 93.7 | 92.5–94.8 | 95.5 | 94.4–96.6 | |

| 5–9 | 1 | 97.0 | 96.4–97.6 | 97.2 | 96.6–97.8 | 97.3 | 95.4–99.1 | 97.3 | 96.5–98.0 | 96.6 | 95.6–97.5 |

| 3 | 93.1 | 92.1–94.1 | 93.6 | 92.5–94.6 | 92.0 | 88.4–95.5 | 92.6 | 91.2–94.0 | 93.9 | 92.5–95.3 | |

| 5 | 90.4 | 89.0–91.8 | 91.1 | 89.7–92.5 | 87.8 | 82.5–93.1 | 89.7 | 87.8–91.6 | 91.3 | 89.4–93.3 | |

| 10–14 | 1 | 92.9 | 91.8–94.0 | 92.9 | 91.7–94.1 | 91.1 | 87.6–94.5 | 93.2 | 91.8–94.6 | 92.4 | 90.6–94.2 |

| 3 | 84.9 | 83.2–86.6 | 86.1 | 84.3–87.9 | 76.8 | 71.1–82.5 | 84.7 | 82.4–86.9 | 85.3 | 82.7–87.9 | |

| 5 | 81.5 | 79.4–83.6 | 82.0 | 79.7–84.4 | 75.6 | 69.4–81.8 | 81.2 | 78.4–84.0 | 81.8 | 78.6–85.0 | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NS, net survival.

Values are age-standardized.

RESULTS

Data meeting the eligibility criteria for analyses came from 37 states comprising 80% of the total US population (Table 2). Of the 17,500 children with ALL, 83.7% were white, 8.9% were black, and 7.4% were of other or unknown race. Almost all cases (98.5%) were morphologically verified (Table 2). There were no differences in morphologic verification by race.

Table 2.

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Numbers of Children (Aged 0–14 Years) Diagnosed During 20012009 and Included in Survival Analyses, With Data Quality Indicators, by US State and Race

| State | No. of Patients |

Morphologically

Verified |

Lost to Follow-Up |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All |

White |

Black |

All |

White |

Black |

All |

White |

Black |

||||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Alabama | 260 | 100.0 | 202 | 77.7 | 54 | 20.8 | 255 | 98.1 | 198 | 98.0 | 53 | 98.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Alaska | 55 | 100.0 | 37 | 67.3 | 1 | 1.8 | 55 | 100.0 | 37 | 100.0 | 1 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| California | 3,309 | 100.0 | 2,819 | 85.2 | 130 | 3.9 | 3,299 | 99.7 | 2,811 | 99.7 | 128 | 98.5 | 578 | 17.5 | 489 | 17.3 | 17 | 13.1 |

| Colorado | 384 | 100.0 | 354 | 92.2 | 5 | 1.3 | 381 | 99.2 | 351 | 99.2 | 5 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Connecticut | 261 | 100.0 | 243 | 93.1 | 9 | 3.4 | 253 | 96.9 | 236 | 97.1 | 9 | 100.0 | 41 | 15.7 | 37 | 15.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Delaware | 52 | 100.0 | 39 | 75.0 | 10 | 19.2 | 50 | 96.2 | 38 | 97.4 | 10 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Florida | 1,096 | 100.0 | 908 | 82.8 | 137 | 12.5 | 1,095 | 99.9 | 907 | 99.9 | 137 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Georgia | 604 | 100.0 | 439 | 72.7 | 137 | 22.7 | 594 | 98.3 | 433 | 98.6 | 134 | 97.8 | 34 | 5.6 | 25 | 5.7 | 7 | 5.1 |

| Hawaii | 91 | 100.0 | 17 | 18.7 | 4 | 4.4 | 90 | 98.9 | 16 | 94.1 | 4 | 100.0 | 43 | 47.3 | 5 | 29.4 | 2 | 50.0 |

| Idaho | 113 | 100.0 | 112 | 99.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 110 | 97.3 | 109 | 97.3 | - | - | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | - | - |

| Iowa | 198 | 100.0 | 188 | 94.9 | 7 | 3.5 | 197 | 99.5 | 187 | 99.5 | 7 | 100.0 | 23 | 11.6 | 22 | 11.7 | 1 | 14.3 |

| Kentucky | 264 | 100.0 | 239 | 90.5 | 19 | 7.2 | 257 | 97.3 | 233 | 97.5 | 19 | 100.0 | 32 | 12.1 | 27 | 11.3 | 3 | 15.8 |

| Louisiana | 255 | 100.0 | 181 | 71.0 | 68 | 26.7 | 253 | 99.2 | 180 | 99.4 | 67 | 98.5 | 65 | 25.5 | 50 | 27.6 | 12 | 17.6 |

| Maryland | 185 | 100.0 | 143 | 77.3 | 34 | 18.4 | 148 | 80.0 | 112 | 78.3 | 31 | 91.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Massachusetts | 472 | 100.0 | 423 | 89.6 | 30 | 6.4 | 472 | 100.0 | 423 | 100.0 | 30 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Michigan | 674 | 100.0 | 564 | 83.7 | 64 | 9.5 | 663 | 98.4 | 557 | 98.8 | 61 | 95.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Mississippi | 137 | 100.0 | 87 | 63.5 | 48 | 35.0 | 133 | 97.1 | 85 | 97.7 | 46 | 95.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Montana | 62 | 100.0 | 54 | 87.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 61 | 98.4 | 53 | 98.1 | - | - | 29 | 46.8 | 25 | 46.3 | - | - |

| Nebraska | 143 | 100.0 | 130 | 90.9 | 9 | 6.3 | 141 | 98.6 | 128 | 98.5 | 9 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| New Hampshire | 103 | 100.0 | 102 | 99.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 103 | 100.0 | 102 | 100.0 | - | - | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | - | - |

| New Jersey | 653 | 100.0 | 519 | 79.5 | 80 | 12.3 | 634 | 97.1 | 508 | 97.9 | 76 | 95.0 | 52 | 8.0 | 38 | 7.3 | 6 | 7.5 |

| New Mexico | 182 | 100.0 | 160 | 87.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 180 | 98.9 | 158 | 98.8 | - | - | 43 | 23.6 | 40 | 25.0 | - | - |

| New York | 1,324 | 100.0 | 1,048 | 79.2 | 159 | 12.0 | 1,300 | 98.2 | 1,031 | 98.4 | 155 | 97.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| North Carolina | 592 | 100.0 | 467 | 78.9 | 87 | 14.7 | 588 | 99.3 | 464 | 99.4 | 86 | 98.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Ohio | 726 | 100.0 | 639 | 88.0 | 58 | 8.0 | 716 | 98.6 | 630 | 98.6 | 57 | 98.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Oklahoma | 268 | 100.0 | 197 | 73.5 | 12 | 4.5 | 264 | 98.5 | 193 | 98.0 | 12 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Oregon | 293 | 100.0 | 254 | 86.7 | 8 | 2.7 | 293 | 100.0 | 254 | 100.0 | 8 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Pennsylvania | 830 | 100.0 | 707 | 85.2 | 80 | 9.6 | 824 | 99.3 | 702 | 99.3 | 80 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Rhode Island | 69 | 100.0 | 66 | 95.7 | 2 | 2.9 | 69 | 100.0 | 66 | 100.0 | 2 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| South Carolina | 235 | 100.0 | 182 | 77.4 | 47 | 20.0 | 233 | 99.1 | 180 | 98.9 | 47 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Tennessee | 331 | 100.0 | 254 | 76.7 | 58 | 17.5 | 329 | 99.4 | 253 | 99.6 | 57 | 98.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Texas | 2,114 | 100.0 | 1,852 | 87.6 | 149 | 7.0 | 2,081 | 98.4 | 1,822 | 98.4 | 147 | 98.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Utah | 226 | 100.0 | 217 | 96.0 | 2 | 0.9 | 226 | 100.0 | 217 | 100.0 | 2 | 100.0 | 27 | 11.9 | 27 | 12.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Washington | 417 | 100.0 | 343 | 82.3 | 25 | 6.0 | 414 | 99.3 | 342 | 99.7 | 25 | 100.0 | 31 | 7.4 | 26 | 7.6 | 4 | 16.0 |

| West Virginia | 97 | 100.0 | 91 | 93.8 | 3 | 3.1 | 94 | 96.9 | 88 | 96.7 | 3 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Wisconsin | 392 | 100.0 | 334 | 85.2 | 22 | 5.6 | 350 | 89.3 | 297 | 88.9 | 19 | 86.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Wyoming | 33 | 100.0 | 29 | 87.9 | 2 | 6.1 | 30 | 90.9 | 26 | 89.7 | 2 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 17,500 | 100.0 | 14,640 | 83.7 | 1,560 | 8.9 | 17,235 | 98.5 | 14,427 | 98.5 | 1,529 | 98.0 | 998 | 5.7 | 811 | 5.5 | 52 | 3.3 |

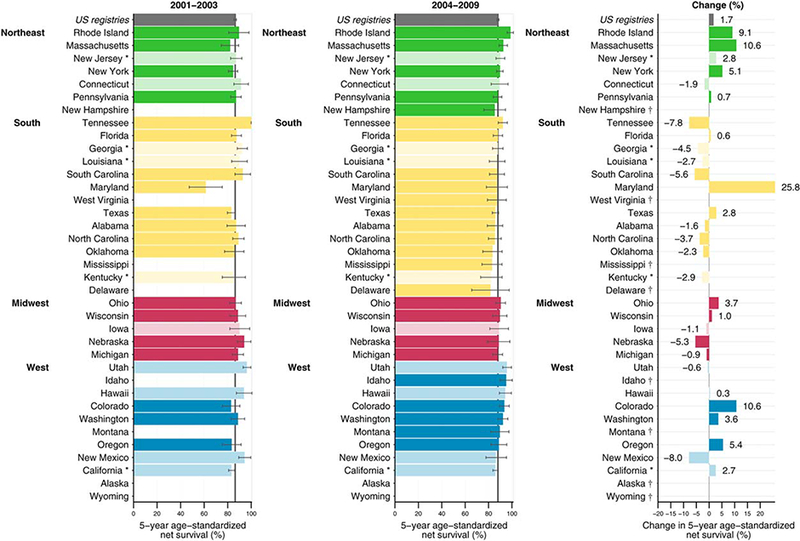

Figure 1 presents a visual snapshot of the absolute change in 5-year age-standardized net survival between the periods 2001 through 2003 and 2004 through 2009 by geographic region. For the United States overall, there was an absolute increase in survival of 1.7% between those periods.

Figure 1.

Age-standardized 5-year net survival (%) and absolute change (%) are illustrated for children (aged 0–14 years) who were diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia during 2 periods (2001–2003 and 2004–2009). The 37 participating states provided 80.6% population coverage of the US. Only age-standardized survival estimates are shown. States are grouped by geographic region and ranked within each region by the survival estimate for 2004 through 2009. Dark-colored bars indicate National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) registries; pale-colored bars, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) programs; asterisks, registries affiliated with both programs. † indicates change (%) was not plotted because at least 1 estimate was not age-standardized.

The 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year age-standardized net survival estimates for all races in the pooled US population represented in this study were 95.3% (95% CI, 94.6%–95.9%), 89.7% (88.8%–90.7%), and 86.4% (95% CI, 85.3%–87.4%), respectively, during 2001 through 2003, and 95.7% (95.3%–96.1%), 90.7% (90%–91.4%), and 88.1% (87.2%–88.9%), respectively, during 2004 through 2009 (Table 3). Despite these increases in survival, disparities still exist between racial groups. For the period 2001 to 2003, 5-year net survival was 86.6% (95% CI, 85.5%–87.7%) for whites but 83.8% (80.3%–87.3%) for blacks. From 2004 to 2009, 5-year net survival increased marginally for whites (88.6%; 87.6%–89.5%) but remained the same for blacks (83.6%; 80.6%–86.6%), resulting in a slight widening of the racial divergence in survival during 2001 through 2009. The 5-year age-standardized estimates for children diagnosed during 2004 through 2009 ranged from 85.2% to 98.6% in the Northeast, from 81.7% to 92.2% in the South, from 87.8% to 90.3% in the Midwest, and from 86% to 95.9% in the West (see Table 1).

Table 3.

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia in Children: Age-Standardized Net Survival (%) at 1, 3, and 5 Years for Children Diagnosed During 2001–2009, by Race and Calendar Period of Diagnosis

| Year | 2001–2003 |

2004–2009 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Races |

White |

Black |

All Races |

White |

Black |

|||||||

| NS (%) | 95% CI | NS (%) | 95% CI | NS (%) | 95% CI | NS (%) | 95% CI | NS (%) | 95% CI | NS (%) | 95% CI | |

| 1 | 95.3 | 94.6–95.9 | 95.3 | 94.6–96.0 | 95.0 | 93.0–97.1 | 95.7 | 95.3–96.1 | 95.7 | 95.3–96.2 | 95.5 | 94.1–96.9 |

| 3 | 89.7 | 88.8–90.7 | 89.8 | 88.8–90.9 | 87.5 | 84.3–90.6 | 90.7 | 90.0–91.4 | 91.2 | 90.5–92.0 | 86.7 | 84.2–89.1 |

| 5 | 86.4 | 85.3–87.4 | 86.6 | 85.587.7 | 83.8 | 80.3–87.3 | 88.1 | 87.2–88.9 | 88.6 | 87.6–89.5 | 83.6 | 80.6–86.6 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NS, net survival.

Five-year net survival for children aged < 1 year, 1 to 4, 5 to 9, and 10 to 14 years were 60.5% (53.4%–67.6%), 92.5% (91.5%–93.5%), 89.2% (87.7%–90.8%), and 79.4% (76.9%–81.9%), respectively, during 2001 through 2003, and 60.1% (54.5%–65.7%), 94.5% (93.7%–95.3%), 90.4% (89%–91.8%), and 81.5% (79.4%–83.6%), respectively, during 2004 through 2009 (Table 1). Survival was highest among children aged 1 to 4 years and lowest among those aged <1 year, with a 30% difference between these age groups in both periods. Survival was consistently slightly higher in girls than in boys, with the largest differences observed in infants aged <1 year throughout 2001 through 2009.

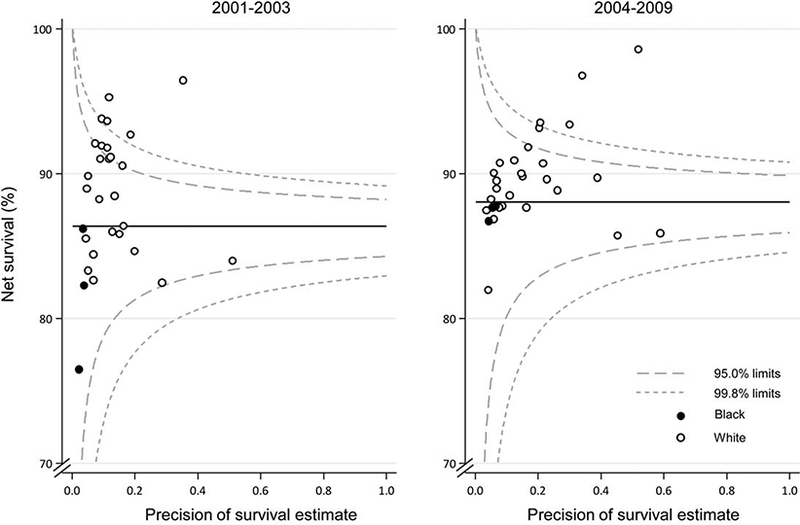

Funnel plots (Fig. 2) illustrate the variation in survival between states and by race. Five-year age-standardized net survival was generally lower among black children (Fig. 2, solid circles) than among white children (Fig. 2, open circles). Net survival estimates for black children were only available for 3 states: this is because of the difficulty of constructing life tables for blacks in some states and in producing age-standardized estimates of net survival due to the small numbers of cases and deaths (see Materials and Methods, above). Similar patterns were observed during 2004 through 2009.

Figure 2.

Age-standardized 5-year net survival (%) is illustrated for children (aged 0–14 years) with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, by calendar period of diagnosis. Each data point represents the survival estimate for a US state for either blacks (3 states) or whites (27 states).

DISCUSSION

In this article, we report the most comprehensive analysis of survival to date among children with ALL in the United States, with data from 37 cancer registries covering 80% of the national population. We observed that short-term survival from childhood ALL in the United States is high. For all participating US states combined, the pooled estimate of 1-year net survival for children diagnosed during 2004–2009 was 95.7% (95% CI, 95.3%–96.1%), whereas 5-year survival was 88.1% (95% CI, 87.2%–88.9%). These 5-year survival estimates from a population-based US cohort are slightly lower but still closely aligned with the 5-year survival estimates of 91.4% from the Children’s Oncology Group ALL randomized trials for a similar period (2000–2005) and the same age group.8 Our results are also within the same range as most countries in Northern and Central Europe5,9 and close to those in Canada (90.6%; 95% CI, 88.6%–92.7%) for 2005 through 2009.9 Our results are consistent with stable incidence rates and decreasing mortality rates for childhood ALL in the United States.10–12

Despite the high overall survival, there were geographic and racial disparities. One-year survival for children diagnosed during 2004–2009 ranged from 91.4% to 98.9% in the Northeast. Differences in 5-year survival were even larger, ranging from 81.7% to 98.6% (see Supporting Table 1). Racial disparities were larger for longer-term survival than for shorter-term survival.

Five-year survival for black children was typically 3% to 5% lower than that for white children. Geographic differences in survival may be explained in part by survival differences between white and black children. Survival is generally lower for black children, and the proportion of black children varies by state. However, we observed that survival for black children was similar to, if not higher than, that of white children in some states (Supporting Table 1). This suggests that the distribution of black and white children does not explain all of the geographic differences in survival. Although genetic polymorphisms may partially explain racial differences in ALL outcomes,33 these differences are more likely to be the reflection of differences in socioeconomic status and access to care.34,35 The survival patterns we observed by race are consistent with higher incidence rates among white children and higher mortality rates among black children.10–12

The patterns of survival by age at diagnosis are consistent with other data from the United States36 and other countries.37 The survival of infants diagnosed with ALL is markedly lower than that for any other age group, which reflects the higher proportion in this age group of children diagnosed with ALL whose profile shows mixed-lineage leukemia gene rearrangements.1 This population-based study confirms previous findings that the highest survival is found among children ages 1 to 4 years, with decreasing survival as age increases toward adolescence.36 Biologic features of childhood leukemia that vary by age and have prognostic implications, such as the DNA index and specific chromosomal rearrangements, may explain differences in survival by age group. The current finding that survival differences in race were most pronounced at age <1 year or >4 years needs further study.37 We also observed that, as previously reported,38 boys have lower survival from ALL than girls. This sex difference was more marked in infants, for whom survival was the lowest, and it remained in the most recent period (2004–2009).

Five-year survival for patients with ALL in the United States is among the highest in the world, and it improved from 83.1% to 87.7% between 1995 and 2009, as reported by the CONCORD-2 study.9 The high survival may reflect in part the intensity of clinical investigations performed to establish the diagnosis, which would be expected to improve the definition of morphologic type and thus the selection of the most appropriate treatment. One indicator of the intensity of diagnosis is the percentage of cases for which microscopic confirmation of the diagnosis was available. For children diagnosed with ALL during the period from 1995 through 2009 covered by the CONCORD-2 study, morphologic verification was available for 98.4% of patients among all US registries combined and ranged between 85.6% and 100% among participating states.9 Morphologic verification, as reported here, was similar among both black and white children diagnosed during 2001 through 2009. The low percentage of cases for which the diagnosis was based on clinical rather than pathologic evidence is not likely to be the result of selective case ascertainment among participating cancer registries, because all registries were certified by the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries as having met data quality and completeness standards.

Clinical Perspective

Important advances in childhood ALL survival have been achieved through both clinical and public health efforts. Clinical advances include improved supportive care and recognition of avenues to reduce the toxicity of therapy without compromising overall outcome. These advances in childhood ALL survival have spanned all age groups, races, and both sexes.36 Clinicians have had increased success with managing the frequent complications of ALL, including tumor lysis syndrome, infection during neutropenia, thrombosis, hemorrhage, anaphylaxis, and suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.39–41 In addition, intrathecal therapy has been used increasingly instead of cranial irradiation for patients with central nervous system disease, thereby reducing radiation-associated morbidity and mortality.33,42 There has been increasing use of immunophe-notyping and cytogenetic characterization to predict outcome and relapse and thus to guide risk-based adjustments in therapy.6‘17 Advanced genetic characterization of ALL can contribute to improved diagnostic evaluation and enhance clinicians’ ability to monitor the response to therapy.17,43 In addition, recent geno-typing techniques have allowed clinicians to detect germ-line differences that may predict response to therapy, as well as chemotherapy-related side effects.33

Cancer Control Perspective

Many of these clinical advances have been achieved in conjunction with public health-related cancer control efforts, including support for clinical trial enrollment.1 Sustained efforts by comprehensive cancer control programs to support clinical trial enrollment for children with cancer are needed to improve survival even further for children with ALL. With survival increasing, cancer control efforts must also focus on the long-term health of childhood ALL survivors.20 Treatment of ALL may result in long-term health effects that may adversely affect the long-term health of childhood cancer survivors. Comprehensive cancer control programs could encourage the adoption of survivorship care plans and support efforts to improve providers’ knowledge of established follow-up guidelines, such as the Children’s Oncology Group long-term follow-up guidelines.44 More widespread implementation of these guidelines could help improve and harmonize providers’ knowledge of potential late effects, screening, evaluation, anticipatory guidance, counseling, and other interventions.44

Comprehensive cancer control programs can also support efforts to reduce disparities among children with ALL. Although there were negligible differences in 1-year survival by race, we observed that black children had lower 5-year survival than white children. This likely reflects differences in access to treatment and may be related to socioeconomic status.45–47 Cancer control efforts that increase access to care among families with lower socio-economic status may help to reduce racial discrepancies in treatment and outcomes.

Limitations

This study did not include young persons aged 15 to 19 years, because it used the framework of the CONCORD-2 study, which used the conventional age range of 0–14 years for children in international cancer studies. Because many previous reports include individuals aged ≥ 15 years in their definition of childhood leukemia, comparing this study with past studies must account for differences in study population age.2,3,10 Records of children diagnosed with leukemia were selected for analysis if their International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition, morphologic code was 1 of the 6 codes proposed by the HAEMACARE Group for ALL.48,49

Although ALL is the most common childhood malignancy worldwide, absolute case numbers are generally small, and caution is needed in interpreting the data. Survival was estimated separately for each state, and estimates covering approximately 80% of the US population were also obtained by pooling the data from all participating states. Survival estimates could not be age-standardized for the less populous states, because the data were sparse. This limitation applies particularly to the comparison of survival between blacks and whites; because, in most states, black children represent fewer than 20% of ALL cases.

Conclusions

Survival from childhood ALL has been improving overall in 37 US states between the periods 2001–2003 and 2004–2009. Because of the relative rarity of childhood ALL, national and international collaboration groups that pool patient numbers and coordinate multicenter research efforts are essential.13 Continued collaboration will be critical in reducing the persistent inequalities in survival from childhood ALL as well as in advancing treatment for childhood ALL. Similar research efforts will continue to play a central role in improving outcomes in other childhood cancers, for which survival is still well below 90%. Comprehensive cancer control programs can support efforts to increase clinical trial enrollment and providers’ knowledge of established follow-up guidelines and to encourage the use of survivorship care plans. Close monitoring of survivors of childhood ALL using population-based cancer registry data are essential to monitor the effect of the implementation of new medical and public health strategies aimed at improving survival.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SUPPORT

Audrey Bonaventure and Michel P. Coleman supported by US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; 12FED03123, ACO12036).

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the CDC.

This Supplement edition of Cancer has been sponsored by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an Agency of the Department of Health and Human Services.

The CONCORD-2 study was approved by the Ethics and Confidentiality Committee of the UK’s statutory National Information Governance Board (now the Health Research Authority) (ref ECC 3–04(i)/2011) and by the National Health Service Research Ethics Service (Southeast; 11/LO/0331).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors made no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith MA, Seibel NL, Altekruse SF, et al. Outcomes for children and adolescents with cancer: challenges for the twenty-first century. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2625–2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64: 83–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steliarova-Foucher E, Stiller C, Kaatsch P, et al. Geographical patterns and time trends of cancer incidence and survival among children and adolescents in Europe since the 1970s (the ACCIS project): an epidemiological study. Lancet. 2004;364:2097–2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katz AJ, Chia VM, Schoonen WM, Kelsh MA. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: an assessment of international incidence, survival, and disease burden. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26:1627–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gatta G, Botta L, Rossi S, et al. Childhood cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007: results of EUROCARE-5—a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:35–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simone JV. History of the treatment of childhood ALL: a paradigm for cancer cure. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2006;19:353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ries LAG, Smith MA, Gurney JG, et al. , eds. Cancer Incidence and Survival Among Children and Adolescents: United States SEER Program 1975–1995 NIH Pub. No. 99–4649. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunger SP, Lu X, Devidas M, et al. Improved survival for children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia between 1990 and 2005: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1663–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allemani C, Weir HK, Carreira H, et al. Global surveillance of cancer survival 1995–2009: analysis of individual data for 25,676,887 patients from 279 population-based registries in 67 countries (CONCORD-2). Lancet. 2015;385:977–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siegel DA, King J, Tai E, Buchanan N, Ajani UA, Li J. Cancer incidence rates and trends among children and adolescents in the United States, 2001–2009. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e945–e955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J, Thompson T, Pollack L, Stewart S. Cancer incidence among children and adolescents in the United States, 2001–2003. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1470–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith MA, Altekruse SF, Adamson PC, Reaman GH, Seibel NL. Declining childhood and adolescent cancer mortality. Cancer. 2014; 120:2497–2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pui CH, Yang JJ, Hunger SP, et al. Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: progress through collaboration. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33: 2938–2948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhojwani D, Yang JJ, Pui CH. Biology of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015;62:47–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stiller CA, Kroll ME, Pritchard-Jones K. Population survival from childhood cancer in Britain during 1978–2005 by eras of entry to clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2464–2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pui CH, Evans WE. A 50-year journey to cure childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Semin Hematol. 2013;50:185–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tasian SK, Loh ML, Hunger SP. Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: integrating genomics into therapy. Cancer. 2015;121: 3577–3590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pritchard-Jones K, Dixon-Woods M, Naafs-Wilstra M, Valsecchi MG. Improving recruitment to clinical trials for cancer in childhood. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:392–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole CH. Lessons from 50 years of curing childhood leukaemia. J Paediatr Child Health. 2015;51:78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winther JF, Schmiegelow K. How safe is a standard-risk child with ALL? Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:782–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mostert S, Sitaresmi MN, Gundy CM, Sutaryo, Veerman AJ. Influence of socioeconomic status on childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia treatment in Indonesia. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1600–e1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suarez A, Pina M, Nichols-Vinueza DX, et al. A strategy to improve treatment-related mortality and abandonment of therapy for childhood ALL in a developing country reveals the impact of treatment delays. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:1395–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metzger ML, Howard SC, Fu LC, et al. Outcome of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in resource-poor countries. Lancet. 2003;362:706–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2014 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. SEER Program Populations, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program,1969–2015. http://www.seer.cancer.gov/popdata.

- 26.Fritz AG, Percy C, Jack A, et al. , eds. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pohar Perme M, Stare J, Esteve J. On estimation in relative survival. Biometrics. 2012;68:113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rachet B, Maringe C, Woods LM, Ellis L, Spika D, Allemani C. Multivariable flexible modelling for estimating complete, smoothed life tables for sub-national populations [serial online]. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spika D, Rachet B, Bannon F, et al. Life tables for the CONCORD-2 study. 2015. Available at: http://datacompass.lshtm.ac.uk/104/. Accessed July 27, 2017

- 30.Stiller CA, Bunch KJ. Trends in survival for childhood cancer in Britain diagnosed 1971–85. Br J Cancer. 1990;62:806–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quaresma M, Coleman MP, Rachet B. Funnel plots for population-based cancer survival: principles, methods and applications. Stat Med. 2014;33:1070–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allemani C, Harewood R, Johnson C, et al. Population-based cancer survival in the US: data, quality control, and statistical methods. Cancer. 2017;123:4982–4993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carroll WL, Hunger SP. Therapies on the horizon for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016;28:12–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abrahao R, Lichtensztajn DY, Ribeiro RC, et al. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in survival among children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in California, 1988–2011: a population-based observational study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:1819–1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lim JY, Bhatia S, Robison LL, Yang JJ. Genomics of racial and ethnic disparities in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2014;120:955–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma H, Sun H, Sun X. Survival improvement by decade of patients aged 0–14 years with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a SEER analysis [serial online]. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonaventure A, Harewood R, Stiller CA, et al. Worldwide comparison of survival from childhood leukaemia for 1995–2009, by subtype, age, and sex (CONCORD-2): a population-based study of individual data for 89,828 children from 198 registries in 53 countries. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4:e202–e217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holmes L Jr, Hossain J, Desvignes-Kendrick M, Opara F. Sex variability in pediatric leukemia survival: large cohort evidence [serial online]. ISRN Oncol 2012:439070, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Einaudi S, Bertorello N, Masera N, et al. Adrenal axis function after high-dose steroid therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:537–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Payne JH, Vora AJ. Thrombosis and acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2007;138:430–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dandoy CE, Hariharan S, Weiss B, et al. Sustained reductions in time to antibiotic delivery in febrile immunocompromised children: results of a quality improvement collaborative. BMJ Qual Saf 2016; 25:100–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vora A, Andreano A, Pui CH, et al. Influence of cranial radiotherapy on outcome in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with contemporary therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:919–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roberts KG, Mullighan CG. Genomics in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: insights and treatment implications. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12:344–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Children’s Oncology Group. Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers. Version 4.0. Monrovia, CA: Children’s Oncology Group; 2013. Available at: http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org. Accessed April 1, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bona K, Blonquist TM, Neuberg DS, Silverman LB, Wolfe J. Impact of socioeconomic status on timing of relapse and overall survival for children treated on Dana-Farber Cancer Institute ALL Consortium protocols (2000–2010). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:1012– 1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adam M, Rueegg CS, Schmidlin K, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in childhood cancer survival in Switzerland. Int J Cancer. 2016;138: 2856–2866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Q, Leisenring WM, Ness KK, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in adverse outcomes among childhood cancer survivors: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1634–1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sant M, Allemani C, Tereanu C, et al. Incidence of hematologic malignancies in Europe by morphologic subtype: results of the HAE-MACARE project. Blood. 2010;116:3724–3734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.HAEMACARE Working Group. Manual for coding and reporting haematological malignancies. Tumori. 2010;96:i–A32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.