Abstract

We conducted a case-control study to compare illicit substance and erectile dysfunction medication (EDM) use between recently HIV-infected and uninfected men who have sex with men (MSM). Eighty-six recently (previous 12 months) HIV-infected MSM (cases) and 59 MSM who recently tested HIV-negative (controls) completed computer-assisted self-interviews. There were no statistical differences in demographics or number of sexual partners by HIV status. Cases were more likely than controls to report methamphetamine or nitrite use, but not EDM, gamma hydroxybutyrate, 3,4 methylenedioxymethamphetamine, cocaine, or marijuana use, in the previous 12 months and with their last three sexual partners in multivariate logistic regression models. Use of nitrites and amphetamine may increase HIV risk among MSM.

Keywords: HIV, Primary infection, Recent infection, MSM, Drug use, Substance use, Methamphetamine, Volatile nitrites, Sildenafil, Erectile dysfunction medication

Introduction

Longitudinal studies have demonstrated associations between HIV seroconversion and use of illicit substances, including amphetamine (Burcham et al. 1989; Chesney et al. 2005; Koblin et al. 2006; PageShafer et al. 1997; Plankey et al. 2007), volatile nitrites (Buchbinder et al. 2005; Burcham et al. 1989; Chesney et al. 2005; Ostrow et. al. 1995; Plankey et al. 2007), and cocaine (Chesney et al. 2005; Ostrow et al. 1995; Plankey et al. 2007). However, relatively few studies have examined substance use in the context of sexual activity. In a recent longitudinal study of men who have sex with men (MSM) in six metropolitan cities in the United States (U.S.), use of illicit substances during sexual activity was associated with HIV seroconversion (Koblin et al. 2006), but associations were not examined by substance type. Another cross-sectional study of MSM from seven U.S. cities examined associations between HIV prevalence and crack cocaine use during sexual activity in the previous 6 months (Harawa et al. 2004), finding no association between substance use and HIV status. However, HIV-infected individuals were not incident cases, therefore temporality between substance use and infection could not be established.

Other studies among MSM have demonstrated associations between unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) and illicit substance use, including use of methamphetamine or amphetamine (Celentano et al. 2006; Chmiel et al. 1987; Colfax et al. 2001, 2005; Hirshfield et al., 2004a, b; Molitor et al. 1998; Rusch et al. 2004; Waldo et al. 2000), volatile nitrites (Choi et al. 2005; Clutterbuck et al. 2001; Ekstrand et al. 1999; Hirshfield et al. 2004a, b; Mulry et al. 1994; Ostrow et al. 1993; Strathdee et al. 1998; Waldo et al. 2000; Woody et al. 1999), 3,4 methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) (Choi et al. 2005; Klitzman et al. 2000, 2002; Lee et al. 2003; Rusch et al. 2004; Waldo et al. 2000), gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB) (Rusch et al. 2004), and ketamine (Rusch et al. 2004). Additionally, recent studies have demonstrated cross-sectional associations between erectile dysfunction medication (EDM) use and UAI (Chu et al. 2003; Hirshfield et al. 2004a; Kim et al. 2002; Mansergh et al. 2006; Paul et al. 2005; Sanchez and Gallagher 2006) and use of other illicit substances (Chu et al. 2003; Crosby and DiClemente 2004: Purcell et al. 2005; Paul et al. 2005; Sanchez and Gallagher 2006). However, some have suggested that associations between substance use and HIV risk behaviors are confounded by personality traits, such as impulsivity (Hayaki et al. 2006; Mccoul and Haslam 2001) and sensation seeking (Kalichman et al. 1996). Additionally, an event-based analysis of drug use and UAI among MSM did not demonstrate an association when using diaries to record sexual events occurring just after substance use (Gillmore et al. 2002), however all substances were collapsed into one measure in the analyses. Comparisons between associations of HIV infection with any substance use vs. associations with substance use during sexual activity may help to elucidate the true relationship between substance use and HIV risk. Using a case-control design, we compared reports of any substance use, regardless of sexual activity, in the previous year and substance use during sexual activity with the last three partners between recently HIV-infected and uninfected MSM to determine which substances may be associated with recent HIV infection.

Methods

Selection of Cases

From May 2002 to February 2006, 200 people with recent HIV infection enrolled in the Acute Infection and Early Disease Research Program (AIEDRP) in San Diego, California, which has been described previously (Daar et al. 2001; Little et al. 1999). Recent infection occurred in the previous 12 months as determined by one of the following: (1) HIV seroconversion within the previous 12 months [negative HIV enzyme immunoassay (EIA) followed by positive EIA]; (2) presence of HIV RNA in plasma, but a negative EIA; or (3) results on a Western blot or detuned EIA that are consistent with early infection. Individuals who were screened for AIEDRP were recruited from local hospitals, physicians’ offices, HIV testing and counseling sites, organizations and establishments that cater to MSM, friends, partners, and other AIEDRP participants. In medical care settings, a clinician or counselor may have informed patients about screening or they may have learned about AIEDRP through a brochure. In other recruitment settings, participants would have been informed by word of mouth or a brochure.

At enrollment, participants were invited to respond to a computer-assisted self-interview (CASI), and 97% did so. Reasons for non-response included inability to speak English (n = 4), withdrawing in the first week of study (n = 2), and declining to complete the CASI (n = 1). Among the remaining 193 respondents, 189 (98%) were men, 181 of whom (96%) reported sexual contact with another man in the previous 12 months. Cases (n = 86) who were eligible for the current study had to (1) be enrolled in AIEDRP with recent HIV infection, (2) report sexual activity with other men in past 12 months, and (3) respond to the CASI between November 2003 and February 2006, at which time respondents were queried about their use of illicit substances and EDM in the previous 12 months and with their last three partners.

Selection of Controls

HIV-seronegative controls were obtained from two sources. Sixty-eight MSM who were screened for AIEDRP, but were not infected with HIV, were invited to complete the CASI, and 66 (97%) did so. Additionally, 38 MSM who received negative EIA HIV tests from the counseling and testing clinics that referred the greatest number of MSM to AIEDRP completed the CASI. All HIV-negative MSM who reported symptoms consistent with acute HIV viremia were screened by HIV RNA, Western blot, and detuned EIA to rule out the possibility of acute HIV infection. Of the 104 HIV-negative MSM recruited from these two sources, 59 were eligible as controls for the current study because they responded to same questions as cases regarding substance and EDM use over the previous 12 months and with their last three partners.

Data Collection

Prior to data collection, all participants completed informed consent and all study protocols were approved by the University of California, San Diego Institutional Review Board. Participants completed CASI within 3 weeks of their HIV diagnosis or last HIV-negative test. Respondents completed CASI in private and were queried about substance use, EDM use, and sexual behavior, including use of EDM or illicit substances at the time of sexual activity with their last three partners and any use in the previous 12 months. The CASI contained many questions pertaining to sexual activity. Participants were queried separately about the number of male and female sexual partners they had in their lifetime and the previous 12, 3, and month prior to interview. Additionally, they were queried about their last three partners in detail including demographics, which assisted in establishing partner gender, substance use during sexual activity, number of sexual events, and the types of sexual activities that occurred including sexual positioning and condom use. EDM use was defined as use of any of the following medications: sildenafil citrate (Viagra®, Pfizer), tadalafil (Cialis®, Eli Lilly), and vardenafil hydrochloride (Levitra®, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKlein, and Schering-Plough). Unfortunately, neither cases nor controls were queried about alcohol use.

Analysis

Differences in demographics and sexual histories between cases and controls were compared using t-tests, Chi-square analysis, and univariate logistic regression. Associations between UAI and use of methamphetamine or nitrites among the last three partners were determined using generalized estimating equations (GEEs). Differences in the proportions of cases and controls reporting substance use were compared using univariate and multivariate logistic regression. In multivariate logistic regression models, each individual substance was analyzed in separate models while controlling for potential confounders. Interactions between EDM and methamphetamine or nitrite use were examined. For further examination of associations between recent HIV infection and methamphetamine and nitrites, an additional substance use variable that included use of both substances alone or together and use of substances other than methamphetamine or nitrites was created. Associations between this variable and HIV status were examined in multiply adjusted logistic regression models and potential interactions between nitrites and methamphetamine were examined. All analyses were conducted using STATA version 8.2 SE (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

The median age of the MSM (n = 145) was 32 (Table 1). Most were white (72.4%), followed by Hispanic (15.2%), African American (6.2%), and Asian or Pacific Islander (4.1%). The median annual income was $30,000, and nearly half completed college (49.7%). More participants were recruited in 2005/2006 than in 2003/2004. The median number of sexual partners reported was 24 (mean 41.2) in the previous 12 months and 6 (mean 12) in the previous 3 months. UAI with any of the last three partners was reported by 88.3% of MSM, with 11.7% reporting no UAI, 16.6% reporting insertive UAI only, 22% reporting receptive UAI only, and 49.7% reporting both insertive and receptive UAI with any of the last three partners.

Table 1.

Demographics, sexual history, and substance use by HIV status (n = 145)

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | HIV-negative (n = 59) % (n) mean (median) |

HIV-positive (n = 86) % (n) mean (median) |

Total (n = 145) % (n) mean (median) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.01 | 0.98, 1.05 | 0.54 | 31.8 (32) | 32.8 (33) | 32.4 (32) |

| White ethnicity vs. all other | 1.11 | 0.53, 2.32 | 0.78 | 71.2 (42) | 73.3 (63) | 72.4 (105) |

| Annual income | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.01 | 0.27 | $37,214 (30K) | $58,279 (32K) | $49,707 (30K) |

| Completed college | 0.65 | 0.34, 1.27 | 0.21 | 55.9 (33) | 45.4 (39) | 49.7 (72) |

| Recruited in 2005/2006 vs. 2003/2004 | 0.21 | 0.10, 0.48 | <0.01 | 83.1 (49) | 51.2 (44) | 64.1 (93) |

| Male sex partners previous 12 months | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.01 | 0.34 | 35.6 (20) | 45.2 (25) | 41.2 (24) |

| Male sex partners previous 3 months | 1.01 | 0.98, 1.02 | 0.69 | 11.4 (6) | 12.6 (6.5) | 12.1 (6) |

| >1 Partner during sex past 12 months | 2.00 | 0.98, 4.06 | 0.06 | 59.3 (35) | 74.4 (64) | 68.3 (99) |

| UAI with last three partners* | ||||||

| 0 of 3 | REF | 11.9 (7) | 11.6 (10) | 11.7 (17) | ||

| 1 of 3 | 0.55 | 0.18, 1.68 | 0.29 | 47.5 (28) | 25.6 (22) | 34.5 (50) |

| 2 of 3 | 1.49 | 0.48, 4.69 | 0.49 | 25.4 (15) | 37.2 (32) | 32.4 (47) |

| 3 of 3 | 1.71 | 0.50, 5.91 | 0.40 | 15.3 (9) | 25.6 (22) | 21.4 (31) |

| Ever incarcerated | 0.48 | 0.22, 1.06 | 0.07 | 30.5 (18) | 17.4 (18) | 22.8 (33) |

| Use with last three partners | ||||||

| Methamphetamine | 1.96 | 0.97, 3.96 | 0.06 | 28.2 (17) | 44.2 (38) | 37.9 (55) |

| Volatile nitrites | 2.75 | 1.37, 5.52 | <0.01 | 30.5 (18) | 54.7 (47) | 44.8 (65) |

| Marijuana | 1.45 | 0.72, 2.99 | 0.30 | 28.8 (17) | 37.2 (32) | 33.8 (49) |

| GHB | 1.93 | 0.79, 4.74 | 0.15 | 13.6 (8) | 23.3 (20) | 19.3 (28) |

| MDMA | 1.75 | 0.58, 5.27 | 0.32 | 8.5 (5) | 14.0 (12) | 11.7 (17) |

| Cocaine | 0.90 | 0.35, 2.30 | 0.83 | 15.3 (9) | 14.0 (12) | 14.5 (21) |

| Polydrug use | 2.18 | 1.10, 4.31 | 0.03 | 35.6 (21) | 54.7 (47) | 46.9 (68) |

| Any drug use | 2.10 | 1.01, 4.37 | 0.05 | 62.7 (37) | 77.9 (67) | 71.7 (104) |

| EDM | 0.97 | 0.45, 2.13 | 0.95 | 23.7 (14) | 23.3 (20) | 23.5 (34) |

| Any use in previous 12 months | ||||||

| Methamphetamine | 1.98 | 1.01, 3.88 | 0.05 | 42.4 (25) | 59.3 (51) | 52.4 (76) |

| Volatile nitrites | 3.82 | 1.90, 7.69 | <0.01 | 39.0 (23) | 70.9 (61) | 57.9 (84) |

| Marijuana | 1.45 | 0.73, 2.86 | 0.29 | 57.6 (34) | 66.3 (57) | 62.8 (91) |

| GHB | 2.00 | 0.95, 4.20 | 0.07 | 23.7 (14) | 38.4 (33) | 32.4 (47) |

| MDMA | 2.31 | 1.09, 4.91 | 0.03 | 22.0 (13) | 39.5 (34) | 32.4 (47) |

| Cocaine | 1.02 | 0.50, 2.06 | 0.96 | 32.2 (19) | 32.6 (28) | 32.4 (47) |

| Polydrug use | 3.65 | 1.76, 7.57 | <0.01 | 50.9 (30) | 79.1 (68) | 67.6 (98) |

| Any drug use | 5.79 | 1.79, 18.8 | <0.01 | 78.0 (46) | 95.4 (82) | 88.3 (128) |

| EDM | 1.46 | 0.75, 2.85 | 0.27 | 40.7 (24) | 50.0 (43) | 46.2 (67) |

Test for trend p = 0.04

There were no significant differences between cases and controls by demographics or number of sexual partners (Table 1). However, cases were significantly less likely to have been recruited in 2005/2006 than controls. Although cases and controls reported UAI with their last three partners in similar proportions, cases were more likely to report UAI with more of their last three partners (p = 0.04). A greater proportion of cases than controls reported having UAI with more than one of their last three partners (62.8% vs. 40.7%, respectively, p = 0.01).

Any illicit substance use was reported by 71.7% of MSM in the previous 12 months and 71.7% with any of their last three partners (Table 1). In the previous 12 months, marijuana use was most commonly reported (62.8%), followed by volatile nitrites (57.9%), methamphetamine (52.4%), EDM (46.2%), cocaine (32.4%), MDMA (32.4%), and GHB (32.4%). With participants’ last three partners, volatile nitrites were most commonly reported (44.8%), followed by methamphetamine (37.9%), marijuana (33.8%), EDM (23.5%), GHB (19.3%), cocaine (14.5%), and MDMA (11.7%). Polydrug use (i.e., use of more than one substance) was also commonly reported. Illicit substance use was reported by a greater proportion of cases than controls (Table 1), including volatile nitrites during sexual activity with their last three partners and nitrites, methamphetamine, and MDMA in the previous 12 months.

In multiply adjusted logistic regression models that examined one substance per model, use of methamphetamine or volatile nitrites with the last three partners (OR = 2.77 and 2.71, respectively) or over the previous 12 months (OR = 2.33 and 3.31, respectively) was reported more frequently among cases than controls (Table 2). There were no significant differences between cases and controls with regard to use of MDMA, ketamine, GHB, cocaine, marijuana, or EDM in the previous 12 months or with their last three partners.

Table 2.

Associations between HIV status and substance use (n = 145)

| Substance | Use in the previous 12 months | Use with the last three partners | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| AORa | 95% CI | p-value | AORa | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Methamphetamine | 2.33 | 1.1, 5.2 | 0.04 | 2.77 | 1.2, 6.6 | 0.02 |

| Volatile nitrites | 3.31 | 1.5, 7.4 | <0.01 | 2.71 | 1.2, 6.2 | 0.02 |

| MDMA | 1.89 | 0.8, 4.5 | 0.15 | 1.09 | 0.3, 3.8 | 0.89 |

| Ketamine | 2.41 | 0.8, 7.7 | 0.14 | 2.13 | 0.2, 10.0 | 0.58 |

| GHB | 1.69 | 0.7, 3.9 | 0.22 | 1.71 | 0.6, 4.9 | 0.32 |

| Cocaine | 0.93 | 0.4, 2.1 | 0.86 | 1.15 | 0.4, 3.4 | 0.80 |

| Marijuana | 1.49 | 0.7, 3.3 | 0.33 | 1.70 | 0.7, 3.9 | 0.22 |

| EDM | 1.02 | 0.5, 2.3 | 0.96 | 0.80 | 0.3, 2.0 | 0.63 |

AOR adjusted odds ratio for age, number of male partners in the previous 12 months, sexual activity with more than one partner at one time in the previous 12 month period, UAI with more than one of the last three partners, history of imprisonment, and recruitment in the last 18 months of study vs. the first 18 months

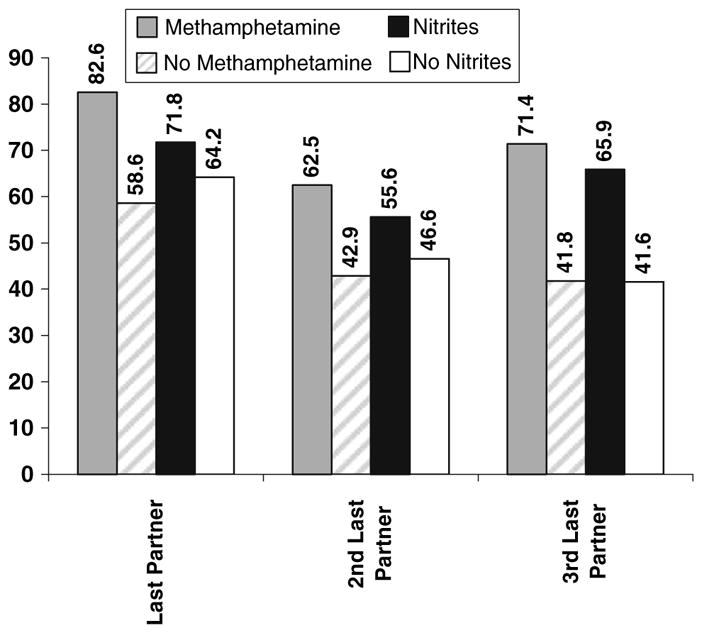

Unprotected anal intercourse was consistently reported by a greater proportion of MSM who used either methamphetamine or nitrites with each of the last three partners (Fig. 1). In GEEs, UAI was significantly associated with use of methamphetamine and nitrites (OR = 3.1, p < 0.01 and 1.8, p = 0.01, respectively) across all three partners regardless of case-control status while controlling for partner type (main vs. all other types). When considering positioning for UAI in GEEs, methamphetamine was associated with UAI regardless of positioning (receptive OR = 2.4, p < 0.01; insertive OR = 1.8, p = 0.02), but nitrite use was only associated with receptive UAI (OR = 1.9, p = 0.01; insertive OR = 1.2, p = 0.40) after controlling for partner type. EDM use was not associated with UAI regardless of sexual positioning. Data on UAI with partners in general in the past 12 months were not available.

Fig. 1.

Percent of methamphetamine or volatile nitrites users compared to non-users reporting UAI with the last three partners (n = 145). Asterisk indicates Associations between UAI and substance use calculated across all three partners using generalized estimating equations and controlling for partner type. GEE analyses indicate significant associations between methamphetamine use and UAI across the last three partners (OR = 3.1; 95% CI: (1.9, 5.0); p < 0.01) and nitrite use and UAI across the last three partners (OR = 1.8; 95% CI: (1.1, 2.9); p = 0.01)

In multivariate models examining associations between HIV status and substance use as a single variable (i.e., no use vs. methamphetamine only vs. nitrites only vs. both nitrites and methamphetamine vs. other substances), cases were more likely to report use of nitrites (OR = 6.20, p = 0.03), or both methamphetamine and nitrites (OR = 8.26, p = 0.01), but not methamphetamine alone in the previous 12 months as compared to controls (Table 3). Additionally, compared to controls, cases were more likely to report use of both methamphetamine and nitrites (OR = 3.23, p = 0.03), but not use of each of these substances alone with their last three partners. No interactions between methamphetamine and nitrite use were observed in models examining use with the last three partners or use in the past 12 months.

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios for associations between HIV status and use of methamphetamine, volatile nitrites, a combination of methamphetamine and volatile nitrites, and other substance use controlling for age, number of male partners in the previous 12 months, sexual activity with more than one partner at one time in the previous 12 month period, UAI with more than one of the last three partners, history of imprisonment, and recruitment in the last 18 months of study vs. the first 18 months (n = 145)

| Previous 12 months | Last three partners | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Substances used | ||||||

| None | REF | REF | ||||

| Methamphetamine only | 3.42 | 0.60, 19.4 | 0.16 | 3.45 | 0.69, 17.2 | 0.13 |

| Volatile nitrites only | 6.20 | 1.20, 32.2 | 0.03 | 2.72 | 0.77, 9.61 | 0.12 |

| Methamphetamine and volatile nitrites | 8.26 | 1.86, 36.7 | 0.01 | 3.23 | 1.12, 9.34 | 0.03 |

| Other substances | 2.80 | 0.60, 13.2 | 0.19 | 0.89 | 0.29, 2.70 | 0.84 |

| UAI with >1 partner among last three | 2.68 | 1.18, 6.10 | 0.02 | 2.66 | 1.16, 6.07 | 0.02 |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.96, 1.05 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.96, 1.05 | 0.85 |

| Imprisonment | 0.24 | 0.09, 0.67 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.08, 0.63 | <0.01 |

| Number of male partners in the previous 12 months | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.01 | 0.55 | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.01 | 0.85 |

| >1 Partner during sex past 12 months | 1.44 | 0.06, 3.45 | 0.41 | 1.68 | 0.69, 4.08 | 0.25 |

| Recruitment in the last 18 months (vs. the first) | 0.19 | 0.08, 0.49 | <0.01 | 0.15 | 0.06, 0.38 | <0.01 |

Discussion

We found significant associations between recent HIV infection and nitrite use and recent HIV infection and methamphetamine use regardless of whether these substances were used during sexual activity with the last three partners or at any time during the previous 12 months. Additionally, cases were more likely to report UAI with more than one of their last three partners than controls. UAI was associated with use of methamphetamine or nitrites with the last three partners regardless of case-control status, suggesting that use of these substances may increase the likelihood of UAI. Use of methamphetamine and nitrites in combination were most strongly associated with recent HIV infection. These associations persisted even though there were very few differences between recently HIV-infected MSM and those who recently tested HIV-negative. Additionally, there were no significant associations between HIV status and EDM use.

The results of this study are consistent with earlier studies. Among six studies that examined associations between HIV seroconversion and use of specific substances, five found significant associations between nitrite use during follow-up and HIV seroconversion (Buchbinder et al. 2005; Burcham et al. 1989; Chesney et al. 2005; Ostrow et al. 1995; Plankey et al. 2007), whereas two found no such association (Koblin et al. 2006; PageShafer et al. 1997). In the six studies that examined amphetamine use, five demonstrated significant associations between amphetamine use and HIV seroconversion (Burcham et al. 1989; Chesney et al. 2005; Koblin et al. 2006; PageShafer et al. 1997; Plankey et al. 2007). However, the remaining study only found such associations prior to adjusting for confounding (Buchbinder et al. 2005). Consistent with two earlier studies (Burcham et al. 1989; Koblin et al. 2006), we did not observe a significant association between recent HIV infection and cocaine use. In contrast, three longitudinal studies (Chesney et al. 2005; Ostrow et al. 1995; Plankey et al. 2007) reported significant associations between HIV seroconversion and cocaine use. These differences may be due in part to substance use trends by year or geographic region, or social–sexual networks surrounding use of certain substances. Additionally, we may have failed to detect an association due to insufficient power, as a greater proportion of MSM reported cocaine use in previous studies (Chesney et. al. 2005; Ostrow et al. 1995; Plankey et al. 2007). On the other hand, substances that have consistently shown no association with HIV seroconversion, such as marijuana (Burcham et al. 1989; Chesney et al. 2005; Koblin et al. 2006; Ostrow et al. 1995; PageShafer et al. 1997), were not associated with incident HIV infection in this study.

In addition to finding associations between recent HIV infection and methamphetamine or nitrite use, we also found associations between UAI and methamphetamine or nitrite use across the last three partners. These data suggest that methamphetamine or nitrite use during sexual activity may increase the risk of HIV through increasing the likelihood of UAI with high-risk partners. Previously, we demonstrated associations between UAI and methamphetamine use among recently infected MSM in this population using the individual as his own control (Drumright et al. 2006), thereby controlling for unmeasured factors (e.g., personality) that may confound associations.

When examined as a single substance use variable that included use of methamphetamine alone, nitrites alone, both methamphetamine and nitrites, or other substances, methamphetamine was not associated with HIV status. There are some potential explanations for the discrepancy between these findings and those demonstrating an association between recent HIV infection and methamphetamine in this study. The number of MSM reporting methamphetamine use only was small [(n = 13 with last three partners (9%), n = 17 in previous 12 months (12%)]. The sample size was larger for nitrite use and even larger for use of both methamphetamine and nitrites, pointing to a potential lack of power when stratifying by use of more than one substance. Additionally, it may be possible that individuals who practice polydrug use are more likely to engage in riskier sexual behaviors such as UAI (Colfax et al. 2005; Ostrow et al. 1993; Patterson et al. 2005), and use of nitrites and methamphetamine together could be representative of polydrug use in this sample. We recommend examining reasons for increased HIV risk among polydrug using MSM in future studies with larger sample sizes.

Surprisingly, we did not observe significant associations between EDM use and HIV status. Previous cross-sectional studies of MSM have demonstrated associations between sildenafil use and serodiscordant UAI (Brewer et al. 2006; Chu et al. 2003; Kim et al. 2002; Mansergh et al. 2006), and between sildenafil use and HIV prevalence (Chu et al. 2003; Paul et al. 2005; Sanchez and Gallagher 2006). However, recently infected and uninfected MSM in our cohort reported EDM use in similar proportions, suggesting that EDM use alone may not be a risk factor for HIV infection. This lack of association could be due to use of EDMs for various reasons including experimental one-time use, to assist in maintaining an erection while using condoms, or for higher risk sexual activity such as combining use with illicit substances. Additionally, only about half of MSM who reported EDM use in the previous year reported use with any of their last three partners, indicating infrequent use. In a recent study of risk factors for syphilis among MSM, sildenafil (Viagra) use in combination with methamphetamine, but not alone was associated with increased risk of syphilis (Wong et al. 2005), suggesting that associations between UAI and EDM use may be confounded by other substance use. In our study there were no interactions between use of EDM and other substances with respect to HIV status.

Although efforts were made to minimize limitations, some may persist. When collecting data on socially sensitive information, there may be a non-differential bias in under-reporting sensitive behaviors. For this reason, CASI was used for data collection as it has been shown to increase reporting of socially sensitive information (Ghanem et al. 2005; Hewitt 2002; Kurth et al. 2004; Perlis et al. 2004; Rogers et al. 2005; Simoes et al. 2006) and may increase validity (Murphy et al. 2000; Paschall et al. 2001; van Griensven et al. 2006). Additionally, interviews were conducted after HIV diagnosis, which may increase the risk of recall bias wherein cases are more likely to overestimate exposure (Schlesselman 1982). Such bias was minimized by keeping participants unaware of the research questions. With any case-control study there is a concern that cases and controls differ with regard to factors that were not studied, however our cases and controls were comparable by demographics and sexual histories. Since this study was conducted in San Diego and only included MSM who were at high-risk for HIV, it may not be generalizable to all MSM.

Although our overall sample size was smaller than previous studies, this study reports on a greater number of recently HIV-infected MSM and demonstrates associations not only between recent HIV infection and substance use during the time period of infection, but also between recent HIV infection and substance use during sexual activity. This study provides evidence that use of methamphetamine or nitrites during sexual activity could increase the risk of HIV acquisition among MSM through potentially increasing UAI. These data are supported by other recent studies that indicate that MSM may be more likely to have UAI with serodiscordant partners when using nitrites (Brewer et. al. 2006; Colfax et al. 2001) and methamphetamine (Brewer et al. 2006; Colfax et al. 2001; Morin et al. 2005). Additionally, this is the first case-control study that we are aware of that examines EDM use as a risk factor for recent HIV infection, demonstrating no significant associations. EDM use may be more likely to be associated with insertive anal intercourse than receptive (Mansergh et al. 2006), which may not carry as high of a risk for HIV acquisition as receptive anal intercourse (Buchbinder et al. 2005; Burcham et al. 1989; Koblin et al. 2006; PageShafer et al. 1997); however we did not observe greater likelihood of insertive anal intercourse or UAI with EDM use alone or in combination with any other substance in this sample of MSM. Further investigation into reasons for EDM use and variation in HIV risk among MSM by different patterns of usage is warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Tari Gilbert, Jacqui Pitt, Paula Potter, Joanne Santangelo, and the University of California, San Diego Antiviral Research Center staff for their support in data collection; and W. Susan Cheng for her assistance in data collection and management. Most of all we would like to thank our participants for volunteering for this study. Funding for this study was provided by: the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, grant # AI43638 (The Southern California Primary Infections Program) and grant # 5 T32 AI07384 (AIDS Training Grant); and the Universitywide AIDS Research Program, grant # ID01-SDSU-056; grant # IS02-SD-701; grant # D03-SD-400; and grant # F06-SD-258.

Contributor Information

Lydia N. Drumright, Division of International Health and Cross-Cultural Medicine, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, Mail code 0622, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA

Pamina M. Gorbach, Department of Epidemiology and Division of Infectious Disease, School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Susan J. Little, Department of Medicine, Antiviral Research Center, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA

Steffanie A. Strathdee, Division of International Health and Cross-Cultural Medicine, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, Mail code 0622, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA

References

- Brewer DD, Golden MR, Handsfield HH. Unsafe sexual behavior and correlates of risk in a probability sample of men who have sex with men in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;33:250–255. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000194595.90487.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchbinder S, Vittinghoff E, Heagerty P, Celum C, Seage G, Judson FN, et al. Sexual risk, nitrite inhalant use, and lack of circumcision associated with HIV seroconversion in men who have sex with men in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;39:82–89. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000134740.41585.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burcham JL, Tindall B, Marmor M, Cooper DA, Berry G, Penny R. Incidence and risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion in a cohort of Sydney homosexual men. The Medical Journal of Australia. 1989;150:634–639. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1989.tb136727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celentano DD, Valleroy LA, Sifakis F, MacKellar DA, Hylton J, Thiede H, et al. Associations between substance use and sexual risk among very young men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;33:265–271. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000187207.10992.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Barrett DC, Stall R. Histories of substance use and risk behavior: Precursors to HIV seroconversion in homosexual men. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;88:113–116. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmiel JS, Detels R, Kaslow RA, van Raden M, Kingsley LA, Brookmeyer R. Factors associated with prevalent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1987;126:568–575. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Operario D, Gregorich SE, McFarland W, MacKellar D, Valleroy L. Substance use, substance choice, and unprotected anal intercourse among young Asian American and Pacific Islander men who have sex with men. Aids Education and Prevention. 2005;17:418–429. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2005.17.5.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu PL, McFarland W, Gibson S, Weide D, Henne J, Miller P, et al. Viagra use in a community-recruited sample of men who have sex with men, San Francisco. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2003;33:191–193. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clutterbuck DJ, Gorman D, McMillan A, Lewis R, Macintyre CC. Substance use and unsafe sex amongst homosexual men in Edinburgh. AIDS Care. 2001;13:527–535. doi: 10.1080/09540120120058058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colfax G, Coates TJ, Husnik MJ, Huang Y, Buchbinder S, Koblin B, et al. Longitudinal patterns of methamphetamine, popper (amyl nitrite), and cocaine use and high-risk sexual behavior among a cohort of San Francisco men who have sex with men. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82:i62–i70. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colfax GN, Mansergh G, Guzman R, Vittinghoff E, Marks G, Rader M, et al. Drug use and sexual risk behavior among gay and bisexual men who attend circuit parties: A venue-based comparison. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2001;28:373–379. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200112010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby R, DiClemente RJ. Use of recreational Viagra among men having sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2004;80:466–468. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.010496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daar ES, Little S, Pitt J, Santangelo J, Ho P, Harawa N, et al. Diagnosis of primary HIV-1 infection. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001;134:25–29. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-1-200101020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drumright LN, Little SJ, Strathdee SA, Slymen DJ, Araneta MRG, Malcarne, et al. Unprotected anal intercourse and substance use among men who have sex with men with recent HIV infection. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;43:344–350. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000230530.02212.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand ML, Stall RD, Paul JP, Osmond DH, Coates TJ. Gay men report high rates of unprotected anal sex with partners of unknown or discordant HIV status. AIDS. 1999;13:1525–1533. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199908200-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanem KG, Hutton HE, Zenilman JM, Zimba R, Erbelding EJ. Audio computer assisted self interview and face to face interview modes in assessing response bias among STD clinic patients. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2005;81:421–425. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.013193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillmore MR, Morrision DM, Leigh BC, Hoppe MJ, Gaylord J, Rainey DT. Does “high = high risk”? An event-based analysis of the relationship between substance use and unprotected anal sex among gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior. 2002;6:361–370. [Google Scholar]

- Harawa NT, Greenland S, Bingham TA, Johnson DF, Cochran SD, Cunningham WE, et al. Associations of race/ethnicity with HIV prevalence and HIV-related behaviors among young men who have sex with men in 7 urban centers in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;35:526–536. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayaki J, Anderson B, Stein M. Sexual risk behaviors among substance users: Relationship to impulsivity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:328–332. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M. Attitudes toward interview mode and comparability of reporting sexual behavior by personal interview and audio computer-assisted self-interviewing—Analyses of the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Sociological Methods & Research. 2002;31:3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfield S, Remien RH, Humberstone M, Walavalkar I, Chiasson MA. Substance use and high-risk sex among men who have sex with men: A national online study in the USA. AIDS Care. 2004a;16:1036–1047. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331292525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfield S, Remien RH, Walavalkar I, Chiasson MA. Crystal methamphetamine use predicts incident STD infection among men who have sex with men recruited online: A nested case-control study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2004b;6:42–49. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.4.e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Heckman T, Kelly JA. Sensation seeking as an explanation for the association between substance use and HIV-related risky sexual behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1996;25:141–154. doi: 10.1007/BF02437933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim AA, Kent CK, Klausner JD. Increased risk of HIV and sexually transmitted disease transmission among gay or bisexual men who use Viagra, San Francisco 2000–2001. AIDS. 2002;16:1425–1428. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200207050-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitzman RL, Greenberg JD, Pollack LM, Dolezal C. MDMA (‘ecstasy’) use, and its association with high risk behaviors, mental health, and other factors among gay/bisexual men in New York City. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;66:115–125. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitzman RL, Pope HG, Hudson JI. MDMA (“ecstasy”) abuse and high-risk sexual behaviors among 169 gay and bisexual men. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1162–1164. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.7.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblin BA, Husnik MJ, Colfax G, Huang YJ, Madison M, Mayer K, et al. Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2006;20:731–739. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216374.61442.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth AE, Martin DP, Golden MR, Weiss NS, Heagerty PJ, Spielberg F, et al. A comparison between audio computer-assisted self-interviews and clinician interviews for obtaining the sexual history. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2004;31:719–726. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000145855.36181.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Galanter M, Dermatis H, McDowell D. Circuit parties and patterns of drug use in a subset of gay men. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2003;22:47–60. doi: 10.1300/j069v22n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little SJ, Daar ES, D’Aquila RT, Keiser PH, Connick E, Whitcomb JM, et al. Reduced antiretroviral drug susceptibility among patients with primary HIV infection. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:1142–1149. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.12.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansergh G, Shouse RL, Marks G, Guzman R, Rader M, Buchbinder S, et al. Methamphetamine and sildenafil (Viagra) use are linked to unprotected receptive and insertive anal sex, respectively, in a sample of men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2006;82:131–134. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.017129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccoul MD, Haslam N. Predicting high risk sexual behaviour in heterosexual and homosexual men: The roles of impulsivity and sensation seeking. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31:1303–1310. [Google Scholar]

- Molitor F, Truax SR, Ruiz JD, Sun RK. Associations with methamphetamine use during sex with risky sexual behaviors and HIV infection among non-injection drug users. Western Journal of Medicine. 1998;168:93–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin SF, Steward WT, Charlebois ED, Remien RH, Pinkerton SD, Johnson MO, et al. Predicting HIV transmission risk among HIV-infected men who have sex with men—Findings from the Healthy Living Project. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;40:226–235. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000166375.16222.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulry G, Kalichman SC, Kelly JA. Substance use and unsafe sex among gay men—Global versus situational use of substances. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy. 1994;20:175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Durako S, Muenz LR, Wilson CM. Marijuana use among HIV-positive and high-risk adolescents: A comparison of self-report through audio computer-assisted self-administered interviewing and urinalysis. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;152:805–813. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.9.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrow DG, Beltran ED, Joseph JG, Difranceisco W, Wesch J, Chmiel JS. Recreational drugs and sexual behavior in the Chicago MACS/CCS cohort of homosexually active men. Chicago Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS)/Coping and Change Study. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1993;5:311–325. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(93)90001-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrow DG, DiFranceisco WJ, Chmiel JS, Wagstaff DA, Wesch J. A case-control study of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 seroconversion and risk-related behaviors in the Chicago MACS/CCS Cohort, 1984–1992. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Coping and Change Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;142:875–883. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PageShafer K, Veugelers PJ, Moss AR, Strathdee S, Kaldor JM, vanGriensven GJP. Sexual risk behavior and risk factors for HIV-1 seroconversion in homosexual men participating in the tricontinental seroconverter study, 1982–1994. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;146:531–542. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschall MJ, Ornstein ML, Flewelling RL. African American male adolescents’ involvement in the criminal justice system: The criterion validity of self-report measures in a prospective study. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2001;38:174–187. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Semple SJ, Zians JK, Strathdee SA. Methamphetamine-using HIV-positive men who have sex with men: Correlates of polydrug use. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82:I120–I126. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul JP, Pollack L, Osmond D, Catania JA. Viagra (sildenafil) use in a population-based sample of U.S. men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2005;32:531–533. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000175294.76494.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis TE, Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR, Arasteh K, Turner CF. Audio-computerized self-interviewing versus face-to-face interviewing for research data collection at drug abuse treatment programs. Addiction. 2004;99:885–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plankey MW, Ostrow DG, Stall R, Cox C, Li X, Peck JA, et al. The relationship between methamphetamine and popper use and risk of HIV seroconversion in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2007;45:85–92. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180417c99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell DW, Wolitski RJ, Hoff CC, Parsons JT, Woods WJ, Halkitis PN. Predicotrs of the use of Viagra, testosterone, and antidepressants among HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men. AIDS. 2005;19:S57–S66. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000167352.08127.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SM, Willis G, Al Tayyib A, Villarroel MA, Turner CF, Ganapathi L, et al. Audio computer assisted interviewing to measure HIV risk behaviours in a clinic population. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2005;81:501–507. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.014266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch M, Lampinen TM, Schilder A, Hogg RS. Unprotected anal intercourse associated with recreational drug use among young men who have sex with men depends on partner type and intercourse role. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2004;31:492–498. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000135991.21755.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez TH, Gallagher KM. Factors associated with recent sildenafil (Viagra) use among men who have sex with men in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;42:95–100. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000218361.36335.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesselman JJ. Case-control studies: Design, conduct, analysis. New York: Oxford University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Simoes AA, Bastos FI, Moreira RI, Lynch KG, Metzger DS. A randomized trial of audio computer and in-person interview to assess HIV risk among drug and alcohol users in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;30:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Hogg RS, Martindale SL, Cornelisse PG, Craib KJ, Montaner JS, et al. Determinants of sexual risk-taking among young HIV-negative gay and bisexual men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology. 1998;19:61–66. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199809010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Griensven F, Naorat S, Kilmarx PH, Jeeyapant S, Manopaiboon C, Chaikummao S, et al. Palmtop-assisted self-interviewing for the collection of sensitive behavioral data: Randomized trial with drug use urine testing. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;163:271–278. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldo CR, McFarland W, Katz MH, MacKellar D, Valleroy LA. Very young gay and bisexual men are at risk for HIV infection: The San Francisco Bay Area Young Men’s Survey II. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2000;24:168–174. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200006010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong W, Chaw JK, Kent CK, Klausner JD. Risk factors for early syphilis among gay and bisexual men seen in an STD clinic: San Francisco, 2002–2003. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2005;32:458–463. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000168280.34424.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody GE, Donnell D, Seage GR, Metzger D, Marmor M, Koblin BA, et al. Non-injection substance use correlates with risky sex among men having sex with men: Data from HIVNET. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;53:197–205. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]