Short abstract

This study uses interview data from public health departments and aging-in-place efforts to explore how alignment between these entities can strengthen the disaster resilience of older adults and identify promising programs or new collaborations.

Keywords: Community Organizations, Community Resilience, The Elderly, Emergency Preparedness, Natural Hazards, Public Health

Abstract

This study uses interview data collected from public health departments and aging-in-place efforts—specifically, from coordinators of age-friendly communities and village executive directors—to explore how current aging-in-place efforts can be harnessed to strengthen the disaster resilience of older adults and which existing programs or new collaborations among public health departments and these organizations show promise for improving disaster resilience for older populations.

Interviews with stakeholders revealed that most age-friendly communities and senior villages did not place a high priority on promoting disaster preparedness. While most public health departments conducted or took the lead on disaster preparedness and resilience activities, they were not necessarily tailored to older adults. Aligning and extending public health departments' current preparedness activities to include aging-in-place efforts and greater tailoring of existing preparedness activities to the needs of older adults could significantly improve their disaster preparedness and resilience. For jurisdictions that do not have an existing aging-in-place effort, public health departments can help initiate those efforts and work to incorporate preparedness activities at the outset of newly developing aging-in-place efforts.

Summary

The increasing frequency and intensity of weather-related and other disaster events combined with the growing proportions of older adults present a new environment in which public health programs and policies must actively promote the resilience of older adults.

Preparedness programs conducted by public health departments are designed to reduce mortality and morbidity and, consequently, will become even more critical, given the increasing proportion of older adults in the United States, largely due to aging baby boomers.

Interviews with stakeholders revealed that most age-friendly communities (AFCs) and senior villages did not place a high priority on promoting disaster preparedness. While most public health departments we interviewed did engage in disaster preparedness and resilience activities, they were not necessarily tailored to older adults.

AFCs and senior village interviewees cited older adults' challenges with communication and low prioritization of the need to plan for disasters. These organizations also acknowledged their limited awareness of disaster preparedness and lack of demand from their constituents to provide services to help their communities be better prepared.

Current aging-in-place efforts can be harnessed to strengthen the disaster resilience of older adults. Existing programs and new collaborations between public health departments and these organizations show promise for improving disaster resilience for older populations.

The work of public health departments and aging-in-place efforts is complementary. Improving the everyday engagement of older adults with family, friends, neighbors, and trusted institutions supports other organizations' and agencies' preparedness work by strengthening informal ties and building information networks. Likewise, the work of helping older adults become more resilient to disasters provides an opportunity for older adults to engage with others and learn skills needed to remain safely living at home as they age.

Aligning and extending public health departments' current preparedness activities to include aging-in-place efforts and greater tailoring of existing preparedness activities to the needs of older adults could significantly improve their disaster preparedness and resilience.

For jurisdictions that do not have an existing aging-in-place effort, public health departments can help initiate those efforts and work to incorporate preparedness activities at the outset of newly developing aging-in-place efforts.

Background: Older Adults and Disasters

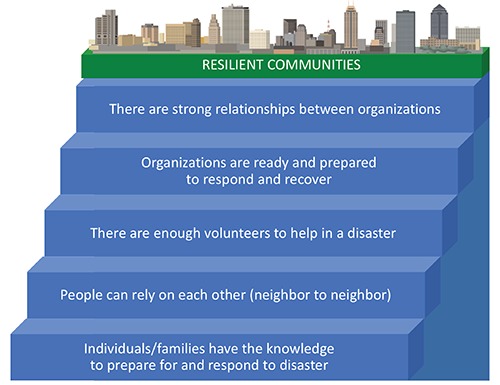

Intense storms and other emergencies have become more frequent and severe in recent years—in part, because of climate change (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Centers for Environmental Information, 2017; National Association of Insurance Commissioners, Center for Insurance Policy and Research, 2017). It is increasingly important to build resilient communities—that is, communities that can recover from disasters and from other problems, such as violence and economic downturns, and emerge stronger and better able to withstand future adverse events (Acosta, Chandra, and Madrigano, 2017). A resilient community (Figure 1) requires strong connections at all levels: between neighbors, between neighborhoods and community organizations, and between local government and nongovernmental groups (Chandra et al., 2011).

Figure 1.

Building Blocks of a Resilient Community

Older adults, defined for this study as adults age 65 or older, are especially vulnerable during and after disasters (Bei et al., 2013; Malik et al., 2017; Weisler, Barbee, and Townsend, 2006). For example, half of the deaths from Hurricane Katrina were adults age 75 and older (Brunkard, Namulanda, and Ratard, 2008), and 63 percent of the deaths after the 1995 heat wave in Chicago were adults age 65 or older (Whitman et al., 1997). Older adults are more likely than others in a community to be socially isolated and have multiple chronic conditions, limitations in daily activities, declining vision and hearing, and physical and cognitive disabilities that hamper their ability to communicate about, prepare for, and respond to a natural disaster (Levac, Toal-Sullivan, and O'Sullivan, 2012; Aldrich and Benson, 2008). A sizable number of adults age 65 or older (about one-third of Medicare enrollees, or approximately 16 million nationally) live alone (Komisar, Feder, and Kasper, 2005). Disasters can also disrupt essential services that allow older adults to live in the community, such as assistance from family caregivers and social services like home-delivered meals, chore services, and personal care (Benson and Aldrich, 2007). A 2012 survey found that 15 percent of U.S. adults age 50 or older would not be able to evacuate their homes without help, and half of this group would need help from someone outside the household (National Association of Area Agencies on Aging, National Council on Aging, and UnitedHealthcare, 2012). A 2014 survey of adults age 50 or older found that 15 percent of the sample used medical devices requiring externally supplied electricity (Al-Rousan, Rubenstein, and Wallace, 2014). Thus, power interruptions could pose adverse health effects for this group.

Older adults can also contribute important assets to disaster response. A 2017 qualitative study of 17 focus groups with at-risk individuals found that adults age 65 or older contribute their experience, resources, and relationship-building capacity to prepare themselves and to support others during an emergency (Howard, Blakemore, and Bevis, 2017). Specifically, older adults both generate and mobilize social capital at the local level during a disaster.

Yet there are critical gaps in disaster preparedness for this group. Although preparedness guidelines and resources exist for older adults, the 2014 survey mentioned earlier found that two-thirds of adults age 50 or older had no emergency plan, had never participated in any disaster preparedness educational program, and were not aware of the availability of relevant resources (Al-Rousan, Rubenstein, and Wallace, 2014). More than a third of respondents lacked a basic supply of food, water, or medical supplies in case of emergency (Al-Rousan, Rubenstein, and Wallace, 2014). Adults age 65 and older will make up nearly 25 percent of the U.S. population by 2060 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). As the U.S. population ages and weather events become more severe, the need to address the vulnerability and leverage the strengths of older Americans in disasters will grow.

Public health and prevention planning and programs are needed to identify older adults at elevated risk in the event of disasters, address their needs, and leverage their strengths (Al-Rousan, Rubenstein, and Wallace, 2014). Public health departments are the government entity primarily responsible for disaster-related public health and safety. However, public health departments are often focused on the entire community, and even their tailored programs may be limited to individuals with functional limitations and may not necessarily meet the needs of all older adults. One set of resources for improving the disaster resilience of older adults may already exist in communities: current efforts to promote aging in place. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009) define aging in place as “the ability to live in one's own home and community safely, independently, and comfortably, regardless of age, income, or ability level.” A 2015 survey found that 75 percent of respondents age 60 or older intended to continue living in their current home for the remainder of their lives, in large part driven by their desire to be near family and friends (National Association of Area Agencies on Aging, National Council on Aging, and UnitedHealthcare, 2015).

There are two primary types of nationwide organizations that promote aging in place in the United States (Greenfield, 2012):

Age-friendly communities (AFCs) are typically collaborations or partnerships between organizations (which may include local government agencies and community groups) that promote the social connectedness of older adults across a municipal or regional area (e.g., cities and counties) and facilitate their inclusion in community life. The World Health Organization oversees the Global Network for Age-Friendly Cities and Communities. AARP oversees a network of U.S. Age-Friendly Cities.

Villages are membership-driven grassroots nonprofit organizations that seek to help older adults age in place successfully through a number of programs and services, such as health education, social gatherings, access to a list of service vendors who have been vetted, transportation, and bookkeeping. Villages generally cover a neighborhood or a city but in some cases can cover multiple adjacent counties in more rural areas. Villages differ based on their size, governance structure, membership characteristics, and regional coverage. The Village to Village Network is a national nonprofit organization that provides expert guidance, resources, and support to help communities establish and maintain villages.

Like resilience, successful aging in place emphasizes connectedness. For older adults in particular, this means engagement with community life and needed services.

The following list summarizes the rationale for focusing on older adults' preparedness and our hypothesis that aging-in-place efforts may serve as resources to public health departments to bolster the disaster resilience of older adults (Keim, 2008):

The U.S. population is aging rapidly, in part because of the aging baby boomer cohorts.

Intense storms and other emergencies have become more frequent and severe over time, and older adults tend to live in areas more prone to disasters.

The majority of older adults in the United States are unprepared for an emergency, and many are socially isolated or are not able to receive or respond to messages typically employed by public health departments.

Older adults are vulnerable and have specific needs in the face of an emergency that are not fully covered by most public health departments' preparedness activities.

Emergency preparedness programs are designed to reduce mortality and morbidity, which will become even more critical, given the aging U.S. population.

Aging-in-place efforts may be a national resource to support disaster resilience of older adults.

Purpose and Methods

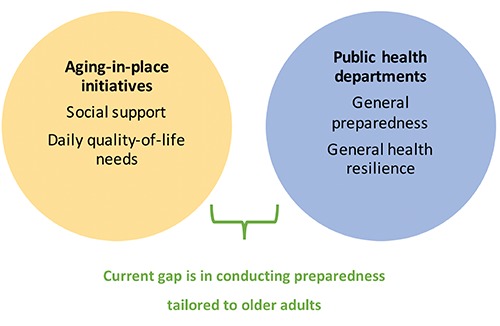

The purpose of this study is to identify the key components to help public health departments, which are charged with general preparedness efforts, and aging-in-place efforts, which strengthen general resilience among older adults, to better align their activities and relationships with each other to fill the gaps in resilience of older adults to disasters (see Figure 2). We sought to answer two main questions: (1) Can current AFC and village efforts to promote aging in place be harnessed to strengthen the disaster resilience of older adults? (2) Which existing programs or new collaborations among public health departments and aging-in-place organizations show promise for improving disaster resilience for older populations?

Figure 2.

Aging-in-Place Initiatives and Public Health Departments Rarely Collaborate to Bolster Preparedness Specific to Older Adults

In 2016, a research team conducted key informant interviews with three groups of stakeholders—public health department staff, AFC leaders, and village executive directors—with three goals in mind:

Improve understanding of what public health departments, AFCs, and villages are currently doing to address disaster resilience in older populations.

Identify promising avenues for improving current efforts or launching new ones, including programs, partnerships, and collaborations.

Gather recommendations for useful metrics of resilience in older adults.

A semistructured protocol was established to guide the interviews with these stakeholders. It included questions about the greatest needs around helping older adults prepare for disasters; the types of resilience activities engaged in by their organizations, both generally and for older adults; other types of older adult–focused programming conducted by their organizations; who leads resilience activities for older adults in their service areas; awareness of and collaboration with other older adult–serving and resilience-focused organizations and agencies in their regions; and ideas for how to assess progress around emergency preparedness and resilience for older adults. While this qualitative research sought to reach saturation of information within each stakeholder group, it is important to note that these results are not representative of all viewpoints for each stakeholder group. All informants gave verbal consent to participate, and the methods were approved by the RAND Corporation's Human Subjects Protection Committee and the Federal Office of Management and Budget.

Village Interviews

We interviewed 16 village leaders from the approximately 175 villages that were operating in early 2016 when we began recruiting interviewees. In most cases, the interviewee was the executive director. We recruited these executive directors with the help of the Village to Village Network, a member-based organization of villages across the United States with a national staff that provides guidance, resources, and support to help communities establish and maintain their villages. Our recruitment strategy was to locate villages representing diversity in size and geographic region across the United States. The villages in our sample were formed between 2008 and 2015 and had been in existence for an average of 5.5 years.

AFC Interviews

Before we began recruiting interviewees in 2016, there were 26 AFCs with completed action plans. With the help of the AARP Public Policy Institute, we recruited leaders from ten AFCs, representing an even distribution across all U.S. geographic regions and rural or urban status. We interviewed these ten leaders, who were generally representatives of the coordinating bodies of a particular AFC. Most respondents were employed by local governments, but a few respondents had primary roles at academic institutions, community foundations, or other types of community-engaged organizations.

Public Health Department Interviews

With assistance from the National Association for County and City Health Officials, we recruited 11 staff members from public health departments. These 11 interviewees were primarily responsible for implementing emergency preparedness and resilience activities. Our sample represented an even distribution across all U.S. geographic regions and rural or urban status, with all departments located in areas that had an AFC in the same jurisdiction. In the case of a county public health department, the city located within the county with the public health department had an AFC. In most cases, participants were emergency preparedness coordinators. The intent of selecting public health departments in an area that had an existing AFC was to identify whether existing entities were aware of their counterparts' activities and how they could be better aligned. To the extent that public health departments are capable and can get leadership buy-in, they can serve as key stakeholders for initiating the development of an AFC or village. This study describes how public health departments, AFCs, and villages can encourage alignment of key goals, complementary activities, and sharing of information to increase preparedness of older adults at the outset of a newly developing aging-in-place effort.

Interviews were led by a member of the research team, with another team member taking detailed notes. Interviews were also audio-recorded. Recordings were referred to for clarification of the written notes and to confirm verbatim quotes, as needed.

Once interviews were complete, two researchers independently reviewed and summarized interview themes for each group. Lead researchers on the project, both of whom participated in conducting interviews, then reviewed the summary of themes, verifying major themes and suggesting clarification or expansion of key points when needed. Themes were then refined and expanded iteratively by the research team.

Results

Prioritizing Preparedness

What Stakeholders Are Doing

Overall, we found that most AFCs did not place a high priority on promoting disaster preparedness. Although villages did promote disaster preparedness activities, most of these focused on building social cohesion and support or on preparing for health-related emergencies. Public health staff generally reported that resilience-building programs for older adults were limited or nonexistent in their agencies. They expressed the view that their mission was preparedness for all age groups in the general population and that older-adult programing typically fell under the jurisdiction of another agency, such as a state or local Department of Aging. Some of their work targeted vulnerable populations or individuals with functional limitations, which may include some but not all older adults.

Villages

The majority of villages were engaged in at least one activity aimed at improving older adults' resilience. The activities varied, based on the needs of the village members, but can be grouped into three general approaches:

information-sharing and outreach, which included providing brochures on preparedness, calling members during and after disasters, and reminding members about changing smoke detector batteries

improving communication with first responders, including help enrolling in smart 911 registries to make responders aware of members' needs, hosting information sessions from local emergency responders, and medical alert systems

assessment and planning, including home safety inspections (e.g., for fire safety), support for emergency planning, and support for advance care planning conversations—that is, wishes in case of death or an incapacitating health event.

About half of the village leaders in our sample noted that their village engaged in some kind of emergency planning. These activities are, as noted, focused mostly on preparing for household emergencies, such as fires or health crises. However, several village respondents drew connections between preparing for disasters and preparing for health-related emergencies as a key component of support for aging in place, since older adults tended to place a higher priority on preparing for health-related emergencies. The village interviewees also noted that despite these activities, many of their members would still be highly vulnerable in the event of natural disaster.

In partnerships and collaborations, villages were more likely to work with nonprofits, such as senior centers, than with government agencies. Many saw the potential value of partnering with public health departments, though some expressed the opposite view—that they did not view public health partnerships as worthwhile because the village lacked the staff time to maintain a partnership, did not know how a partnership would benefit their work, or were concerned that partnering with government agencies might bring with it regulations that would restrict the activities of the village.

AFCs

In general, AFCs were less engaged than villages in activities that focused explicitly on disaster resilience. Unlike villages, which are “bottom-up” membership organizations created to address the needs of their members, AFCs are more “top down”; their activities center on the model set forth by the World Health Organization and AARP, which identifies eight domains: the built environment, transport, housing, social participation, respect and social inclusion, civic participation and employment, communication, and community support and health services (World Health Organization, 2017).

None of these domains explicitly address disaster resilience or preparedness, and most AFC respondents did not see a clear intersection between these domains and disaster preparedness. Of the ten AFC respondents, only three were engaged in resilience activities. These three AFC respondents expressed the view that preparedness was an extension of their work on neighborhood cohesion and social engagement. The leader of one of these AFCs articulated the viewpoint that improving the everyday engagement of older adults with family, friends, neighbors, and trusted institutions supported other organizations' and agencies' preparedness work by strengthening informal ties and building information networks. Each of these three AFC leaders observed that their activities were filling a role in helping to link community preparedness in general with the specific needs of older adults and that bridging this gap—rather than delivering any specific services—may be the best way to support older-adult preparedness.

AFCs that used a community-engaged strategy to set priorities were less likely to focus on resilience and disaster preparedness because these are typically of less immediate interest to older adults than the daily quality-of-life issues addressed in the eight domains. In contrast, AFCs that were formally affiliated with multiple city agencies or issue-specific organizations typically had more diverse agendas that left more room for considering resilience and disaster preparedness in some form.

In terms of partnerships and collaborations, AFCs are almost entirely collaborative efforts, often involving community leaders and representatives of city or local government agencies, which in some cases included public health departments. Most of the AFCs in our sample were staffed by a combination of government employees (whose participation was part of their jobs), community leaders, interns, and volunteers.

Public Health Departments

All of the public health departments in our sample were engaged in preparedness planning and education. In most cases, the planning focused on preparing for health emergencies or the health-specific piece of a disaster event, such as rapid medication dispensing or containing infectious diseases. Most public health departments did not have objectives or programs specific to older adults. As noted earlier, they typically did not perceive programming for older adults to be “in their lane.” However, some had programs focused on individuals with functional limitations (also called at-risk or vulnerable populations). Some also had programs related to chronic disease prevention and management (e.g., depression and diabetes), as well as reduction of health risks, such as tobacco use and fall prevention. All of these issues disproportionately affect older adults. Many public health department leaders felt that their programs had broad relevance to older adults and, therefore, felt that they met the needs of older adults adequately.

With respect to partnering activities, all of the public health departments in our sample described extensive collaboration and coordination with other municipal agencies. Some partnered with area agencies focused on aging to disseminate information about health promotion programs for older adults. Others participated in larger regional coalitions to promote health and wellness goals that were part of a broader strategic plan.

In addition, most public health leaders described collaborations with nongovernmental groups and community organizations, such as hospital systems, churches, and charities (e.g., the Red Cross and Catholic Charities). Their motivation for these partnerships was to use local networks and communication channels to deliver public health messages and to conduct education and outreach. One additional type of engagement with older adults that a few public health departments mentioned was outreach to older adults to recruit volunteers for disaster exercises, such as a medication-dispensing exercise during a public health emergency. One public health leader alluded to the fact that this volunteer opportunity for older adults engages people in a practical way while providing an opportunity for preparedness education more generally. This is just one example of how older adults are an asset for bolstering community resilience.

Some public health leaders expressed interest in partnering or coordinating with nonprofit organizations and other government agencies to conduct outreach directed to older adult populations, though none currently did so. About half of public health departments worked with long-term care facilities or other residential facilities for older adults to help those facilities plan for emergencies. Any nursing home accepting Medicare or Medicaid is required by law to have an emergency plan (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012a), and all public health departments appeared proactively engaged with these sites to develop plans for evacuation or sheltering in place and conducted education activities with residents in conjunction with the facilities. Most public health leaders indicated they were aware of a local AFC, but only two reported interacting with AFC leadership on preparedness activities. Very few public health leaders reported being aware of villages in their community, and none reported interacting with them on preparedness activities. Of the 11 public health leaders we interviewed, seven were from communities with one or more villages. In several cases, the public health department leaders did not look to the AFC or village for collaboration because another government agency was tasked with focusing on older adult–focused programming (although not related to preparedness activities), and, therefore, those public health departments did not consider themselves to be the agencies that would directly partner with the AFCs or villages. Similarly, village leaders and AFCs did not view public health departments as a primary partner for older adult–focused programming. However, there was strong agreement among public health leaders that their departmental missions had significant overlap with those of AFCs, such that a potential collaboration with either type of organization would be well aligned with agency goals.

Recap of Key Findings on Stakeholder Activities

AFCs and villages focused on successful aging in place, helping older adults function in and stay connected to their communities. Many, especially villages, were engaged in programs directly relevant to disaster preparedness, although they did not view these programs as a high priority. Public health departments focused on disaster preparedness, as well as preventing and managing chronic disease among the local population, but they did not have programs targeted specifically to older adults. Public health departments did have programs for individuals with functional limitations (which can encompass some older adults, but not all), but public health leaders did not view programming for all older adults as their responsibility.

Gaps in Preparedness Activities

We explored AFC, village, and public health department views of how well their preparedness-related activities aligned with the greatest needs that older adults face. All acknowledged ongoing gaps in this alignment.

AFCs

AFCs acknowledged gaps between the greatest needs of older adults and the available services or support for preparedness. AFC respondents identified several areas of preparedness needs for older adults, including challenges related to communication, connectedness, and individual planning (e.g., lack of planning around specific health needs, medication management, lack of transportation, and medical needs).

Most AFC respondents suggested that certain needs are more common among older adults during a disaster response. For example, transportation or health needs are paramount for older adults and, if left unaddressed, can prevent older adults from being resilient following a disaster. Providing or obtaining appropriate transportation for people with functional disabilities (e.g., dialysis or nonemergency medical transport) may present major challenges in the event that evacuation is necessary. Similarly, older adults who use medical equipment or supplies (such as supplemental oxygen), rely on home care services, or need medications may experience health care disruptions due to loss of power, interruption of services, or inability to get to an open pharmacy. This could create a serious situation that compounds the wider emergency event in a given location. According to respondents, understanding these unique needs and planning for them—on the part of individuals, public health departments, and first responders—is an area of great need.

The ability of municipalities or first responders to track vulnerable and/or isolated individuals was also identified as a gap. A few respondents raised the corollary of functional disability registries that are kept by some cities, but they cited challenges related to getting people signed up for these registries and maintaining them in a way that would be useful during an emergency. The issue of communication and tracking of vulnerable older adults related to one AFC respondent's belief that developing social cohesion was one of the greatest preparedness needs of older adults. In this respondent's view, older people are more likely to be vulnerable, isolated, and cautious and to need trustworthy relationships with neighbors, friends, organizations, or others who can reach them or be reached out to in an emergency.

A few AFCs also cited the readiness of first responders and emergency management personnel as an area of need for older adults and people with disabilities. Respondents believed that emergency services were not always mindful of or equipped to address the unique needs of the older adults in their communities and that further education and training was needed.

Villages

Village leaders noted that too few members were educated or took action, which was sometimes based on members' failure to prioritize or take seriously the potential benefits of preparedness. Consequently, village leaders noted that their ability to promote preparedness among their members was limited, based on the lack of interest or willingness to engage.

A related challenge for village members, discussed more generally in the context of service provision, is that many members' needs are dynamic; as members deal with acute health events and subsequent recovery or face more steady declines in health, their needs and impairments will change. This relates to preparedness and resilience because, in light of the fluctuating medical needs of village members, gaps in preparing for those medical needs will have to be continually assessed and reassessed.

Public Health Departments

Public health respondents cited several reasons that older adults may be more vulnerable in the event of an emergency. Respondents focused on older adults' health and medical needs, including medication, medical equipment, and functional limitations; social isolation—that is, being more likely to live alone and less likely to know neighbors; and lack of awareness and preparedness for emergencies. Lack of knowledge about preparedness and lack of readiness were viewed as problems for older adults, but respondents noted that this challenge is also widespread in the general population. Nevertheless, older adults might be less aware of preparedness guidelines and recommendations for emergency response; less likely to make a plan and build a kit; and less able to activate an emergency plan when needed, such as evacuating or going to a shelter. Most respondents described older adults as generally lacking the technological skills needed to use a cell phone or computer to follow news or social media updates during an emergency; this puts older adults at risk of being disconnected from emergency response information. Another special need of older adults with regard to emergency response is transportation; when walking to a shelter is not feasible for an urban resident, or if an individual no longer drives, lack of transportation is likely to pose a serious challenge to timely evacuation.

Public health leaders also pointed to gaps in the national policy and legal framework intended to protect older adults as part of emergency preparedness. Most of the policies that guide U.S. disaster preparedness, response, and recovery (e.g., the National Response Framework, the National Disaster Recovery Framework, the Homeland Security Act, the Stafford Act) do not specifically address planning, preparedness, or resilience of older adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012a). One exception is the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act, which focuses on public health and medical preparedness and response and provides grants to strengthen state and local public health security infrastructure. This policy permits the Secretary of Health and Human Services to require those receiving grants to include the state-level agency responsible for aging-related issues in their preparedness plans (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012b). A complementary policy, the Older Americans Act, requires state and local area agencies that address aging to engage in preparedness planning. Each agency is required to develop a preparedness plan for how it will coordinate with private, nonprofit, and government disaster response agencies. In addition, state agencies on aging are required to be involved in the development, revision, and implementation of their state's public health emergency preparedness and response plan. Much like the public health policy, this requirement for preparedness planning is tied to grant funding for these state and local aging agencies (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012b).

Despite these requirements, our findings highlight the lack of a single lead agency responsible for preparing or protecting older adults during a disaster. For most of the public health departments in our sample, the public health leader was not assigned this responsibility. In fact, few locations had any agency or department specifically addressing older adults' preparedness or resilience; rather, the focus was on vulnerable populations, in which older adults were often overrepresented (e.g., those with functional disabilities), but which were not defined in an age-specific way.

Respondents from the larger public health departments in our sample also pointed to gaps and limitations in interagency collaboration around emergency preparedness and management. Respondents noted how collaboration with many other agencies working on preparedness planning required them at times to limit their own plans and scope. For example, some respondents explained their lack of programming and outreach to older adults by the fact that another agency or department was the lead agency for older adult–focused services, and, therefore, they did not perceive a need to address this population.

Barriers Encountered by Stakeholders

We asked those stakeholders who expressed interest in preparedness activities for older adults about barriers to including them in their program portfolios. They pointed to three types of barriers:

limited knowledge or awareness of the problem, including the perception that disaster preparedness for older adults was outside their organizational mission or scope

lack of demand from constituents

resource constraints.

Limited Knowledge or Awareness

A barrier commonly cited by stakeholders was limited awareness or knowledge. In some cases, stakeholders, particularly AFC and village leaders, were not aware that disaster preparedness for older adults was its own field of activity or had only passing acquaintance with the specific issues. In other cases, stakeholders did not see alignment between these activities and the goals and missions of their organizations. While stakeholders generally understood the value of resilience for older adults, they often perceived that other organizations were responsible for this. Public health departments perceived that agencies for aging played this role. Many AFC and village leaders felt that other organizations were already doing this work in their local area.

Lack of Demand from Constituents

In villages, the constituents are the older adult members; in AFCs, the constituents are organizational leaders who commit to improving community conditions in a predefined set of domains developed by the World Health Organization and AARP. Although these constituents are slightly different, the priorities for AFC and village constituents are similar to each other because the focus is on aging older adults, whereas public health departments focus on emergency preparedness mostly without customization to older adults. AFCs and villages prioritized social engagement issues and social services for older adults in large part because constituents in AFCs and villages were focused on day-to-day problems and improving overall quality of life. AFC and village leaders believed that their constituencies did not necessarily see the value of helping them to be more resilient to disasters because they were not as visible as quality-of-life issues, nor did they see possible connections between those efforts and helping them become more resilient in daily life.

Resource Constraints

Resource constraints were a barrier for AFCs and villages. Many AFCs had minimal dedicated staff and had to prioritize activities and programs. As noted, they often did not perceive preparedness as a priority. Village leaders whose organizations did not engage in preparedness activities typically had even less “bandwidth” for taking these on. Villages also noted limitations in their ability to provide high-quality preparedness support, as the small dedicated staff and volunteers generally did not have expertise in preparedness education.

Suggested Metrics to Track Older Adult Resilience

We also asked our interviewees what type of metric would be important to assess in order to measure or track whether older adults in an area were more resilient over time. Respondents focused mainly on individuals' preparedness knowledge and what tangible steps have been taken. For example, they suggested measuring the number of people who have developed a plan, including knowing whom to call in an emergency or where to go for information, and have phone numbers of their family members or caregivers written down.

Other suggestions included

conducting focus groups among older adults with diverse functional status and service agencies targeting older adult populations to assess the needs and interests of older adults around preparedness

evaluating the penetration of outreach efforts and uptake of information and activities

tracking health service utilization, such as emergency room visits, over time to understand the impact of targeted preparedness activities on health crises during an emergency (this respondent expected improved preparedness to avert health crises in the event of a disaster)

at the higher level of organizational preparedness, assessing how many supportive service agencies, such as nursing home visiting programs, have response plans, communications plans, and continuity-of-operations plans in place to assist older adults during an emergency.

Insights for Stakeholders

The interviews supported our hypotheses that the activities of AFCs, villages, and public health departments are supportive of each other: Public health departments' efforts to build resilience to disasters among older adults will help them age in place more successfully, and the work of villages and AFCs to better manage chronic disease and reduce social isolation can help make older adults more resilient to disasters. The recognition of the alignment and extension of these efforts to expand current preparedness activities for AFCs and villages and more tailoring of existing preparedness activities among public health departments to older adults could significantly improve the preparedness and resilience of older adults. Although the findings from these qualitative interviews are not representative of all villages, AFCs, and public health departments, we offer some recommendations for next steps to improve older adults' disaster preparedness and resilience, based on the data we collected within this limited sample recruited from the entire population of these three stakeholder groups across the United States.

Recommendations for AFCs

AFCs are public-private partnerships, with representation from local government and community members. They are well positioned to provide leadership in cultivating positive relationships between older adults, public health departments, and emergency management agencies.

They can also facilitate improved communication and outreach by public health departments to older adults.

More broadly, AFCs can amplify and support other agencies' work—rather than duplicate their effort—by leveraging existing programming and expanding dissemination of the work.

Some AFCs felt the need to focus on everyday quality-of-life issues or basic-needs issues in order to maintain value in the eyes of end users, sponsors, and partners. AFC leaders noted that these constituents may not perceive the relevance of preparedness to quality of life or making cities more livable for older adults. We suggest that AFCs could hone their messaging around resilience, perhaps linking it more broadly to other health-related and quality-of-life issues, in order to increase the salience of disaster preparedness for older adults as a strand of the AFCs' work.

In addition, AARP and the World Health Organization could also consider more explicitly linking preparedness and resilience to one of the eight livability domains in their framework—or adding a ninth domain focused on these issues. Likewise, preparedness permeates many, if not all, of the domains, such as social participation, communication and information, community and health services, and transportation. Social cohesion can improve immediate supports available to older adults, information-sharing is critical in the event of an emergency, and building contingencies in transportation needs is paramount to facilitate access to medications and medical services, such as dialysis, in the case of an interruption of power or services.

Recommendations for Villages

Villages can cultivate relationships with local resources that promote emergency preparedness (public health, emergency management, and first responders). This is important for villages—especially for small to mid-size villages that lack the staffing capacity or resources to design their own preparedness educational materials or curriculum. Small villages and those with resource constraints were able to offer some preparedness programming or guidance to their members when there were local resources in the community.

In cases where local resources are lacking, the national Village to Village Network resources might offer technical assistance by providing information on the types of entities that conduct preparedness and ideas for how village leaders can make connections, as well as providing national preparedness and resilience resources tailored for older adults.

Having local preparedness partnerships and strong programming around preparedness does not guarantee uptake by village members; lack of member interest and/or perceived need was noted as a barrier to doing effective preparedness work.

However, our interviews showed a high interest among nearly all villages—and their members—related to planning for or preventing health emergency events, and nearly all villages offered services related to preparing for health events (e.g., medical alert systems and the Vial of Life and File of Life programs, which ask participants to gather necessary medications and health information in case of emergency). Thus, one critical way to increase the salience of preparedness activities to villages and their members is for advocates in these communities to focus on core resilience activities. These are activities that cut across a variety of health and medical stresses and emergencies, natural and man-made disasters, economic and social threats, and stresses that are present every day and not just during a large-scale disaster—such as having a list of contacts, documentation of health information, extra supplies on hand, and a way to communicate without power. Focusing on these activities could motivate people who are more comfortable focusing on day-to-day quality-of-life issues and stresses, rather than on preparing for an event that may or may not occur (e.g., a hurricane). Village members may be more motivated and willing to put time into these activities if they perceive them as having broad applicability or multiple benefits beyond the disaster scenario that might be easier to ignore as unlikely.

Villages need to learn more about playing an effective role in preparedness for their members. Several village leaders seemed intimidated by the idea of supporting preparedness for their members because of lack of training or knowledge or the inability to provide comprehensive services.

Villages may need to be coached into understanding the unique role and value they can add to preparedness for older adults in their communities—namely, that villages can be a trusted broker to connect members to other services and information. Villages can also work with partners to develop messaging that draws connections between resilience dealing with everyday stress and health-related emergency preparedness and disaster resilience.

Recommendations for Public Health Departments

Public health departments need to be able to reach older adults who might be socially isolated and have limited communication or information channels. They could consider testing “reverse 911” systems that enable emergency management or other authorities to distribute recorded information to non-cellular home telephone numbers through automated calling and promoting “opt-in” registries, in which older adults could elect to make first responders or emergency management agencies aware of their location and their needs so that they could be located and supported in the aftermath of an emergency.

Public health departments could conduct or participate in research to identify best practices related to these types of communication and tracking systems and help disseminate this information across AFCs, villages, and national networks of public health departments. To help disseminate these tracking systems, educational efforts may be needed to help older adults recognize their assets and vulnerabilities. Successful dissemination could spur collaboration around the development or enhancement of these types of systems in other locations. For example, following Hurricane Katrina, a 2014 study in New Orleans highlighted public health efforts to use Medicare data to identify individuals who use electricity-dependent medical equipment in an effort to improve their disaster preparedness (DeSalvo et al., 2014). This spurred the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to create the emPOWER map for hospitals, first responders, electric companies, and community members to find Medicare beneficiaries with electricity-dependent equipment who may be vulnerable to prolonged power outages (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016).

Health and social services agencies that have contact with older adults, such as home care, dialysis centers, nursing homes, and hospice care, could play a larger role in helping their users prepare for disasters. These agencies should also set up continuity-of-operations plans so that the vital medical or nutritional services they provide their clients are not disrupted in the event of an emergency. Health care coalitions were also cited as collaborative organizations that can assist with preparedness for older adults. These coalitions are defined by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services as a multiagency network of health care organizations and public- and private-sector partners that assist with preparedness, response, recovery, and mitigation activities related to health care organization disaster operations (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, undated).

Recommendations for Researchers

Research into effective preparedness practices for older adults is still developing as a field. More evaluation of existing practices is needed to identify promising practices, and, ultimately, evidence-based practices, for improving preparedness and resilience among older adults.

In addition, researchers need to continue to track barriers and progress toward addressing gaps identified in this study.

Recommendations for Policymakers

Given the remaining gaps in preparedness activities for older adults and the lack of plans or a designated entity to address these gaps, policymakers at all levels of government, particularly at the state and community levels, need to agree on a lead entity that is accountable for older adults' protection and resilience. Current funding mechanisms for public health departments dictate the prioritization of deliverables that, in most cases, do not require tailoring services to older adults. Current policies that need to be addressed include consideration of older adults' unique needs in responding to disaster and subsequent recovery. Government could also agree on a standard definition of these needs, which differ from the needs of vulnerable populations at large, especially because of older adults' high level of social isolation. Because AFCs and villages play an important role in helping older adults bolster their resilience, public health departments and other government leaders within jurisdictions that do not have an aging-in-place effort can help an AFC or village build connections with those organizations to more formally incorporate preparedness of older adults at the outset.

Given the ability of older adults to generate and mobilize social capital after a disaster, current policy should also acknowledge them as an asset. Engaging older adults in preparedness education and improving their social cohesion could improve not only their preparedness but also their general well-being, providing synergistic effects for both public health departments and aging-in-place efforts. Experience over time will suggest additional specific ways that older adults can be leveraged as assets. Given the changing demographic landscape of the U.S. population, the bolstering of older adult preparedness is a key way to build community resilience.

Note

This research was sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and was conducted by RAND Health.

References

- Acosta J. D., Chandra A. and Madrigano J. An Agenda to Advance Integrative Resilience Research and Practice: Key Themes from a Resilience Roundtable. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; 2017. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1683.html RR-1683-RWJ. As of December 14, 2017: [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich N. and Benson W. F. “Peer Reviewed: Disaster Preparedness and the Chronic Disease Needs of Vulnerable Older Adults,”. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2008;Vol. 5(No. 1):1–7. pp. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rousan T. M., Rubenstein L. M. and Wallace R. B. “Preparedness for Natural Disasters Among Older U.S. Adults: A Nationwide Survey,”. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;Vol. 104(No. 3):506–511. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301559. pp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bei B., Bryant C., Gilson K. M., Koh J., Gibson P., Komiti A., Jackson H. and Judd F. “A Prospective Study of the Impact of Floods on the Mental and Physical Health of Older Adults,”. Aging & Mental Health. 2013;Vol. 17(No. 8):992–1002. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.799119. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson W. F. and Aldrich N. CDC's Disaster Planning Goal: Protect Vulnerable Older Adults. Atlanta, Ga.: CDC Healthy Aging Program; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brunkard J., Namulanda G. and Ratard R. “Hurricane Katrina Deaths, Louisiana, 2005,”. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2008;Vol. 2(No. 4):215–223. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e31818aaf55. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Healthy Places Terminology,”. 2009. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/terminology.htm last reviewed October 15. As of November 1, 2017:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Identifying Vulnerable Older Adults and Legal Options for Increasing Their Protection During All-Hazards Emergencies: A Cross-Sector Guide for States and Communities. Atlanta, Ga.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012a. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/emergency/pdf/guide.pdf As of November 1, 2017: [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Authorities Addressing Vulnerable Older Adults,”. 2012b. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/emergency/legal/federal.htm last updated March 14. As of November 1, 2017:

- Chandra A., Acosta J., Howard S., Uscher-Pines L., Williams M., Yeung D., Garnett J. and Meredith L. Building Community Resilience to Disasters: A Way Forward to Enhance National Health Security. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; 2011. https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR915.html TR-915-DHHS. As of December 14, 2017: [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSalvo K., Lurie N., Finne K., Worrall C., Bogdanov A., Dinkler A., Babcock S. and Kelman J. “Using Medicare Data to Identify Individuals Who Are Electricity Dependent to Improve Disaster Preparedness and Response,”. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;Vol. 104(No. 7):1160–1164. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302009. pp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield E. A. “Using Ecological Frameworks to Advance a Field of Research, Practice, and Policy on Aging-in-Place Initiatives,”. The Gerontologist. 2012;Vol. 52(No. 1):1–12. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr108. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard A., Blakemore T. and Bevis M. “Older People as Assets in Disaster Preparedness, Response, and Recovery: Lessons from Regional Australia,”. Ageing & Society. 2017;Vol. 37(No. 3):517–536. pp. [Google Scholar]

- Keim M. E. “Building Human Resilience: The Role of Public Health Preparedness and Response as an Adaptation to Climate Change,”. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;Vol. 35(No. 5):508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.022. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komisar H. L., Feder J. and Kasper J. D. “Unmet Long-Term Care Needs: An Analysis of Medicare-Medicaid Dual Eligibles,”. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing. 2005;Vol. 42(No. 2):171–182. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_42.2.171. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac J., Toal-Sullivan D. and O'Sullivan T. L. “Household Emergency Preparedness: A Literature Review,”. Journal of Community Health. 2012;Vol. 37(No. 3):725–733. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9488-x. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S., Lee D. C., Doran K. M., Grudzen C. R., Worthing J., Portelli I., Goldfrank L. R. and Smith S. W. “Vulnerability of Older Adults in Disasters: Emergency Department Utilization by Geriatric Patients After Hurricane Sandy,”. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2017;Vol. 44:1–10. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2017.44. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Area Agencies on Aging, National Council on Aging, and UnitedHealthcare. The United States of Aging Survey. 2012. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/livable-communities/learn/research/the-united-states-of-aging-survey-2012-aarp.pdf As of November 1, 2017:

- National Association of Area Agencies on Aging, National Council on Aging, and UnitedHealthcare. The United States of Aging Survey. 2015. https://www.ncoa.org/resources/usa15-full-report-pdf/ As of December 12, 2017:

- National Association of Insurance Commissioners, Center for Insurance Policy and Research. “Natural Catastrophe Response,”. 2017. http://www.naic.org/cipr_topics/topic_catastrophe.htm last updated July 28. As of November 1, 2017:

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Centers for Environmental Information. “Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Table of Events,”. 2017. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/events/US/1980-2017 As of November 1, 2017:

- U.S. Census Bureau. “Profile America Facts for Features—Older Americans Month: May 2017,”. 2017. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/newsroom/facts-for-features/2017/cb17-ff08.pdf March 27. As of November 1, 2017:

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response. “Hospital Preparedness Program: An Introduction,”. 2017. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/hpp/Documents/hpp-intro-508-old.pdf undated. As of November 1.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “HHS emPOWER Map 2.0,”. 2016. https://empowermap.hhs.gov last updated December 30. As of November 1, 2017:

- Weisler R. H., Barbee J. G., IV and Townsend M. H. “Mental Health and Recovery in the Gulf Coast After Hurricanes Katrina and Rita,”. JAMA. 2006;Vol. 296(No. 5):585–588. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.5.585. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman S., Good G., Donoghue E. R., Benbow N., Shou W. and Mou S. “Mortality in Chicago Attributed to the July 1995 Heat Wave,”. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;Vol. 87(No. 9):1515–1518. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.9.1515. pp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. “Age-Friendly in Practice,”. 2017. https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/age-friendly-in-practice/ As of November 1, 2017: