Short abstract

This study synthesizes evidence on the outcomes, costs, and benefits of early childhood programs, including those that provide early care and education, home visiting, parent education, government transfers, and combinations of approaches.

Keywords: Child Health, Childhood Development, Parenting, Preschool, School Readiness, Social Services and Welfare, Toddlers

Abstract

The past two decades have been characterized by a growing body of research from diverse disciplines—child development, psychology, neuroscience, and economics, among others—demonstrating the importance of establishing a strong foundation in the early years of life. The research evidence has served to document the range of early childhood services that can successfully put children and families on the path toward lifelong health and well-being, especially those at greatest risk of poor outcomes. As early childhood interventions have proliferated, researchers have evaluated whether the programs improve children's outcomes and, when they do, whether the improved outcomes generate benefits that can outweigh the program costs. This study examines a set of evaluations that meet criteria for scientific rigor and synthesizes their results to better understand the outcomes, costs, and benefits of early childhood programs. The authors focus on evaluations of 115 early childhood programs serving children or parents of children from the prenatal period to age 5. Although preschool is perhaps the best-known early childhood intervention, the study also reviewed such programs as home visiting, parent education, government transfers providing cash and in-kind benefits, and those that use a combination of approaches. The findings demonstrate that most of the reviewed programs have favorable effects on at least one child outcome and those with an economic evaluation tend to show positive economic returns. With this expanded evidence base, policymakers can be highly confident that well-designed and -implemented early childhood programs can improve the lives of children and their families.

Prominent developmental theories from psychology, neuroscience, economics, and other disciplines have continued to affirm the importance of the early years for promoting lifelong health and well-being. Motivated by these theories, targeted and universal interventions, starting as early as the prenatal period, have evolved to address the various stressors and other risk factors in the first few years of life that can compromise healthy development. As these early childhood interventions have proliferated, researchers have evaluated whether the programs improve children's outcomes and, when they do, whether the improved outcomes generate benefits that can outweigh the program costs. This study examines a set of evaluations that meet criteria for scientific rigor and aggregates the results to better understand the outcomes, costs, and benefits of early childhood programs. We focus on evaluations of early childhood programs serving children or parents of children from the prenatal period to age 5. Although preschool is perhaps the best-known early childhood intervention, our study also evaluated such programs as home visiting; parent education; health-related visits; and government transfer programs, such as food and housing subsidies.

Overall, we found that most early childhood programs improve one or more outcomes for children and that, where formal benefit–cost analyses (BCAs) have been performed, most programs largely pay for themselves through benefits to participants, government, and other members of society. More specifically, our study sought to answer three questions:

What program approaches to providing services for families and children from the prenatal period to school entry have been rigorously evaluated?

What outcomes did these programs improve in the short or long term?

What are the costs and benefits of effective programs and returns to government or society?

In doing so, we build on two prior RAND studies. In 1998, we published Investing in Our Children (Karoly, Greenwood, et al., 1998), one of the first policy reports to synthesize the available evidence on the effectiveness that different early childhood interventions have for children's outcomes. It identified ten programs with rigorous evaluations and estimated positive economic returns for two that were most amenable to BCA. In 2005, Early Childhood Interventions: Proven Results, Future Promise (Karoly, Kilburn, and Cannon, 2005) expanded on the original research—examining the effectiveness of 20 programs and seven BCAs. This work demonstrated that many benefits of childhood programs continue into adulthood and that the economic returns of five programs more than covered the program costs.

Since 2005, the field has decidedly evolved, and the evidence continues to accumulate. The present study therefore aimed to bring our understanding of the effects of early childhood programs up to date. Using criteria to define the nature of the early childhood programs of interest and the required rigor for the accompanying evaluation, we identified 115 programs to be the focus of our review. Relative to our prior reports, this study examines a broader scope of the programs, also encompassing early childhood programs that are health-focused, are government transfers, are implemented in community-based settings, and take a two-generation approach. For 25 of the 115 programs, we also identified a formal economic evaluation defined as a cost analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), or BCA. Following a systematic process for reviewing each study, we used methods, including meta-analysis and metaregression, to synthesize the evidence for the programs we identified.

In the remainder of this article, we highlight key findings with respect to each of the three study questions. We conclude by identifying implications of our findings for policy, practice, and future research.

What Types of Early Childhood Programs Have Been Rigorously Evaluated?

We identified 115 programs aimed at ultimately improving outcomes for children that had evaluations meeting our criteria for scientific rigor. At the same time, many programs currently lack a research base that met our screening criteria and therefore are not captured in our review. For the set of programs included in our analysis, we first characterized the program approach and the nature of the evaluation.

Evaluations Cover Varied Approaches to Early Childhood Programs

Drawing on a conceptual framework of how early childhood programs contribute to child outcomes, directly through child development inputs, by increasing parenting capacity, or both, we identified four primary approaches that we labeled

early care and education (ECE): 35 programs providing services to children in a group setting, such as preschools or formal play groups, to promote child development

home visiting: 30 programs providing individualized services to primarily parents in a home-based setting to promote parent skills and knowledge

parent education: 18 programs providing group or individualized services to parents in a non–home-based setting to improve parent skills and knowledge

transfers: seven programs providing cash or in-kind benefits (such as vouchers for food or nutrition, child care, housing, or health care) directly to families.

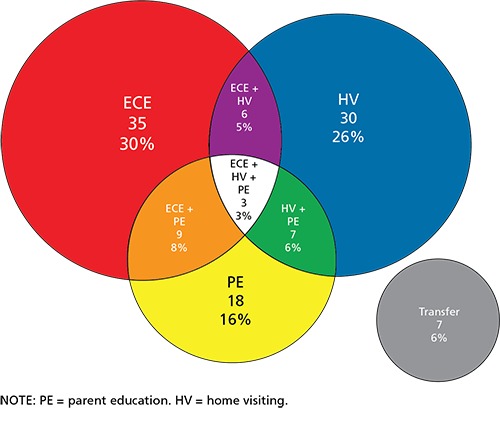

Of the 115 programs we reviewed, 78 percent took primarily one of these four approaches, and the rest used a combination of approaches (nine programs combining ECE and parent education; seven that combine parent education and home visiting; six that combine ECE and home visiting; and three that combine ECE, home visiting, and parent education) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Early Intervention Programs Included in the Study, by Approach

The programs also varied in other ways, although some approaches were more common:

focal person: Most programs interacted primarily with parents, primarily with children, or both. Other intended participants included teachers and health care providers. Programs typically delivered services either one-on-one or in a group-based setting, although some used both.

targeting mechanism: Almost all programs were designed to serve at-risk or otherwise disadvantaged children and families, typically defined by low incomes. Only a few of the programs we reviewed (18) served families and children universally, without regard to their characteristics.

starting age: By our selection criteria, the programs began during the prenatal period up to school entry. The dominant starting ages were during infancy (0 to 11 months) or preschool ages (36 to 60 months), in part reflecting the dominance of home visiting and ECE programs in our analysis set. Less common were programs that began in the prenatal period or with toddlers.

length of intervention: Most programs provided services for less than a year (the typical ECE or parent education program), although 23 programs (mostly home visiting alone or in combination) offered services for three years or more.

Evaluations Measured Short- and Longer-Term Outcomes in Multiple Domains

The evaluations we reviewed—nearly all of which used randomized-control trials to compare outcomes for those participating in a given program with outcomes for those who are not—examined 3,183 child outcomes. We grouped the measured outcomes into 11 broad domains. About 75 percent of the outcomes examined fall under the first three domains:

behavior and emotion (e.g., social skills, internalizing behaviors)

cognitive achievement (e.g., literacy, self-regulation)

child health (e.g., birth outcomes, body-mass index [BMI], access to health care, nutrition)

developmental delay (e.g., mental development, physical development, general)

child welfare (e.g., maltreatment, abuse, neglect)

crime (e.g., involvement by child or parent with courts, police, criminal activity)

educational attainment (e.g., years of schooling, attendance, special education)

employment and earnings in adulthood

family formation in adulthood

use of social services in adulthood

composite measures of multiple domains.

Some outcomes were measured over the short term, either during the intervention or soon after it ended. When follow-up of program participants continued, evaluations captured the impact on outcomes for participating children during the school-age years or even adulthood. More than half of the programs we analyzed measured at least one child outcome past the immediate end of the program, and 13 measured outcomes more than ten years later.

In addition to the outcomes examined and length of the follow-up, the evaluations we reviewed varied by such characteristics as the time period during which they were performed, program scale, and evaluation sample size. The included programs had evaluations that spanned the past 50 years, although most were conducted for cohorts of program participants in the 1990s and 2000s. With the exception of transfer programs, the evaluation studies were most commonly model demonstrations conducted at the local level rather than multistate or national scale. Consequently, sample sizes for treatment and control groups combined tended to be small: More than half of all programs had maximum evaluation cohort sizes of fewer than 300, and the median size across programs was 244.

Which Outcomes Did Early Childhood Programs Improve?

We designated each child outcome measured in an evaluation as positive, negative, or null (meaning that there was no statistically significant difference between participants and nonparticipants for the outcome being measured). For example, if a program was shown to decrease a child's BMI and the measured impact was statistically significant, we deemed the outcome positive, or favorable.

Early Childhood Programs Can Improve an Array of Early and Later Outcomes

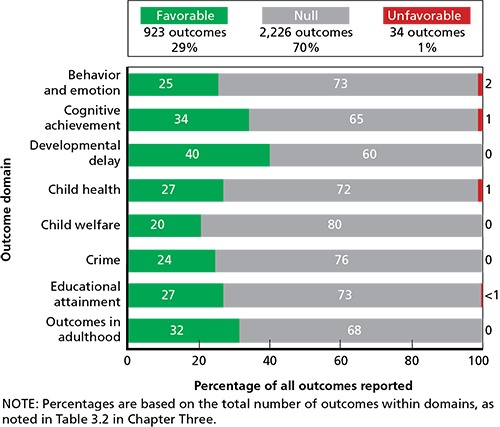

Across the 115 programs we reviewed, 102 (89 percent) had a positive effect on at least one child outcome, indicating that it is relatively rare, among published evaluations, to find programs that have no demonstrable impacts on child outcomes. Almost one in three outcomes were improved: Twenty-nine percent of outcomes (923) were positive, only 1 percent (34 outcomes) were negative, and the rest were null. The domains of cognitive achievement and developmental delay saw larger shares of positive outcomes than the other domains did (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Favorable, Null, and Unfavorable Distribution of Outcomes, by Domain

Early childhood programs have long been considered one of the few policy areas for which evidence demonstrates that they work. As a result, it might come as a surprise that less than one-third of all outcomes measured were demonstrably positive. However, statistically, one would expect one in 20 outcomes to improve at random; the fact that this analysis shows improvement in roughly six of 20 outcomes is meaningful.

Sizes of Improvements in Outcomes Varied

Policymakers care not only whether improvements exist but also about their magnitude. Research methods known as meta-analysis and metaregression can be used to summarize, across programs, how large the impacts are.

Prior meta-analyses of early childhood programs have demonstrated that the impacts from early childhood programs can be sizable. Our 2005 study found an average effect size for early cognitive skills measured near the beginning of elementary school of 0.33 for nine ECE programs combined with other approaches (home visiting or parent education) and 0.21 for six programs that were either single-approach home visiting or parent education programs (Karoly, Kilburn, and Cannon, 2005). These magnitudes are consistent with other meta-analyses of early intervention programs, which suggest a range of significant impacts for various early intervention approaches on child outcomes of 0.1 to 0.4, in which most syntheses have estimated effect sizes for the cognitive achievement or the behavior and emotion domain.

We add to the literature on the size of impacts from early childhood programs by conducting meta-analysis and metaregression on outcomes in the child health domain, which has typically not been examined in meta-analyses of early childhood programs. We estimated the size of impacts for three outcome categories in the child health domain: birth outcomes, BMI, and substance use. We selected this subset because these categories included a relatively large number of outcomes and studies with measures reported in common metrics, included at least five programs that measured the outcomes, and they span early childhood to adult outcomes. We also selected these three for analysis because they are measures of child health outcomes per se, unlike some of the other categories in the child health domain, which measured child health inputs, such as emergency-department visits and hospitalizations, timely immunizations, and child access to health care.

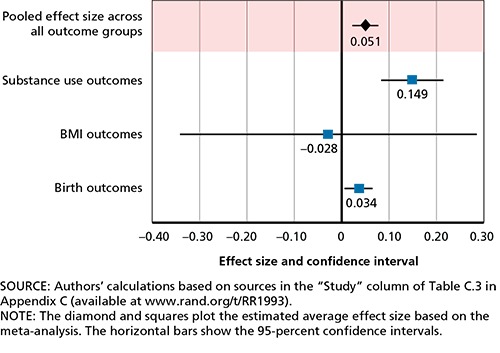

The estimated average effect size, based on meta-analysis for the three health-related domains combined, is small (0.05), but it masks variation across the three domains (see Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Pooled Effect Sizes and Confidence Intervals, by Outcome Category and for All Three Health Outcome Categories Combined

birth outcomes: The size of the improvement in birth outcomes is very small (effect size of 0.03). This is in line with many other recent meta-analyses that have found little effect that lifestyle and other interventions during pregnancy have on pregnancy outcomes. It is noteworthy that none of the effects is negative.

BMI outcomes: The results indicate that early childhood programs in our sample did not have a preventive effect on BMI at later ages in elementary school (i.e., a null effect size). In fact, two programs had the unintended effect of increasing BMI.

substance use outcomes: On average, substance use outcomes had a modest effect (effect size of 0.15). The program participants' outcomes clearly exceeded those of the control groups, and, given that early childhood programs serve very young children, the effects are relatively large compared with effects for substance use programs delivered in adolescence.

Overall, when we examined how the size of program effects varied by approach, we found that ECE programs had larger effects than other program approaches for the three health outcomes that we analyzed. In addition, the magnitude of the effects declined in the past half century, with more-recent evaluations having smaller effects than earlier ones. This is likely due to the experiences of the control group changing over time, such that many children in the control group today also receive some alternative services, whereas control group children in earlier decades were unlikely to have received any services.

What Are the Costs and Benefits of Early Childhood Programs?

Out of the 115 programs included in this study, 25 were the subject of formal economic evaluation, which came in three forms:

cost analysis: the resources required to implement a given program and the foundation for a CEA or BCA

CEA: the cost to obtain a given outcome. Alternatively, a CEA can report the amount of an outcome obtained for each dollar invested.

BCA: the economic value of all program effects relative to the program cost. Metrics include net benefits (benefits minus costs) or the benefit–cost ratio (benefit divided by cost).

In seeking to value all outcomes, BCA is the most comprehensive of the three methods and preferred for use with early childhood programs, which often affect multiple outcomes. Reflecting this preference, the available economic evaluations we examined are predominantly BCAs, with a small number of cost analyses and CEAs. The growth over time in economic evaluations of early childhood programs reflects the increased demand for evidence of the resources required to implement a program and the potential economic returns. At the same time, some form of economic evaluation, even a formal cost analysis, remains the exception rather than the rule.

The Resources Required for Early Childhood Programs Vary Widely

The evidence from cost analyses for 25 programs—either a stand-alone analysis or one conducted as part of a CEA or BCA—shows tremendous variation in the per-child or per-family costs. As measured in 2016 dollars, the cost estimates range from about $150 per family for a parent education program to nearly $48,800 per family for a program that combined ECE with home visiting, among other comprehensive services. The variation is almost as large among programs that use the same approach. For example, the cost for the six home visiting programs ranges from about $720 per family to nearly $10,200 per family. Much of this variation within and across program approaches can be traced to key program features, such as the intensity and duration of the services delivered. Because most cost analyses are specific to the location where the program was implemented, some of the variation also reflects differences in local prices for personnel, facilities, materials, and other required resources.

Most Programs with Benefit–Cost Analyses Show Positive Returns, but Those Results Are Not Guaranteed

The 19 early childhood programs with BCAs reviewed in this study demonstrate that positive economic returns are possible but are not realized for every program. Positive returns mean that the dollar value of the program's observed or projected effects on child or parent outcomes exceeds the program costs, where the comparison accounts for the fact that program costs are typically incurred up front, while benefits accrue over time, potentially over the child's lifetime.

Findings from the analysis of the economic returns for the 19 programs include the following:

Benefit–cost ratios are typically in the range of $2 to $4 for every dollar invested, although higher ratios are possible. This occurs when very low-cost programs have an effect on costly outcomes, such as health care costs. Higher returns are also evident for more resource-intensive programs that have longer-term follow-up and thereby capture effects on parent and child outcomes with larger economic consequences (e.g., earnings, crime).

Positive economic returns have been demonstrated for three of the four main approaches we identified and many of the combination approaches. Both less and more resource-intensive programs can show positive returns, as can programs using both targeted and universal approaches.

The monetary benefits from early childhood programs derive from multiple outcome domains, and they can be due to improved outcomes for the children, the parents, or both. Earnings (of the parent or child) are often the single largest source of benefits. Another major source of benefits can be public- and private-sector savings from reductions in crime, although few of the interventions we reviewed have evidence measuring effects on crime, either for participating parents or their children.

Benefits to the government (federal, state, and local), albeit positive in many cases, are not always large enough to offset the program cost. It is possible that, with longer-term follow-up, programs would generate further savings to government that could help to cover the program cost.

The benefits of early childhood investments unfold over time and can take years or even decades to reach the point at which cumulative benefits exceed the up-front costs. This reflects the fact that the participating child's earnings in adulthood are often a major source of benefits, and such benefits do not begin to accumulate until the participating child reaches adulthood 15 to 20 years after the program began. There are exceptions when programs with a modest up-front investment generate immediate effects on such outcomes as use of medical services or parent economic outcomes (e.g., employment, criminal activity).

Programs that do not show positive returns either have no significant impacts or have affected outcomes that could not be valued in dollars and counted as an offset to program costs. It is possible that a more comprehensive BCA based on longer-term follow-up or measurement and monetization of other outcomes would show positive net benefits for these programs.

Overall, the results from 19 BCAs reviewed in this study demonstrate the proof of the principle that early childhood programs can generate economic benefits that outweigh program costs. At the same time, it is important to recognize that there is considerable uncertainty in estimates of economic return, reflecting the precision with which program effects are measured, the inability to assign an economic value to all outcomes that are affected, and the absence of measurement for many potential outcomes, including those that will take time to be realized.

There Is Scope to Improve the Application of Economic Evaluation to Early Childhood Programs

The paucity of economic evaluations that accompany impact evaluations of early childhood programs reflects several factors. Researchers conducting a program outcome evaluation often lack the expertise to also measure program cost. Where comprehensive cost estimates are available, implementing a BCA can be challenging. Notably, many of the outcomes affected by early childhood programs are not readily expressed in monetary values so that they can be aggregated and compared with program cost. Furthermore, because BCA methods vary across studies, apples-to-apples comparisons are not possible, which limits the ability to identify the programs with the largest “bang for the buck.” Improvements in the quality and comparability of economic evaluations can only strengthen the usefulness of these methods for decisionmakers seeking to make efficient use of available resources.

This Study Has Implications for Multiple Stakeholders

For Policymakers and Practitioners

Research on early childhood program effectiveness and economic returns can help inform how decisionmakers in the public and private sectors set policy with respect to such programs and how practitioners implement them. Our findings have implications both policy and practice.

Policymakers can be highly confident that well-designed and well-implemented early childhood programs can improve the lives of children and their families. This study describes multiple approaches to early childhood intervention that have been rigorously demonstrated to improve child outcomes and more than pay for their costs. Although not every program improves every outcome, evidence is strong across time, locations, and program models that most of the early childhood programs we identified improve some child outcomes.

With a robust base of early childhood programs that have been proven to be effective based on rigorous evaluation, decisionmakers should integrate other criteria when selecting programs to implement. With multiple proven programs from which to choose, decisionmakers can go beyond considering only whether a program is “evidence-based” to incorporate other criteria, such as the fit with the community's needs, the desired outcomes, the population to be served, and the available assets and resources. Numerous resources can help communities identify the best programmatic fit.

Program implementers adopting or expanding evidence-based models should pay attention to quality of replication and effects of scale-up. Selecting evidence-based programs helps increase the chances of achieving the desired outcomes, but programs must be implemented with fidelity to be effective. Fidelity of implementation is important because most of the program evaluations we have reviewed tell us that an early childhood program works but not which features were responsible for the demonstrated outcomes (the so-called black box). Further, given that many of the effective programs documented in this study were undertaken as smaller-scale demonstration projects, it is important to address fidelity and program quality in the context of program scale-up. The growing field of implementation science and increasing technical assistance associated with funding streams, such as the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program and Head Start, provide support for effective implementation.

New approaches to universal programs raise the possibility that they can complement rather than substitute for targeted programs. An ongoing debate in early childhood programming has been whether a program should seek to serve all families or target those with greater needs. A new generation of universal programs demonstrates that the approaches can be employed together. For example, Durham Connects provides a low-intensity home visiting program to all families while identifying children and families that might benefit from additional, more-intensive services.

Benefits can take decades to exceed costs, posing challenges for funding mechanisms that require short-term payoffs. Social impact bonds and other pay-for-performance mechanisms are increasingly being used to attract private financing for early childhood programs. These mechanisms are premised on the expectation that shorter-term impacts on program participants will produce public-sector savings that can be used to pay back the private investors' up-front financing. Programs in areas that, for example, improve parents' earnings, reduce health care costs, or decrease the use of other social welfare benefits for parents can be more amenable to these financing mechanisms than programs with outcomes that take longer to realize.

For Researchers

Our synthesis of research evidence points to opportunities and challenges for the research community to further advance its understanding of early childhood program effectiveness and economic impact. Our findings have implications for ongoing dissemination of the research evidence.

Decisionmakers would benefit from head-to-head comparisons of early childhood programs. For many program models, it is becoming increasingly challenging to establish a control group that does not experience the early childhood program of interest. There also are more evidence-based early childhood programs from which to choose. Decisionmakers would benefit from research that makes explicit head-to-head comparisons of the program alternatives.

The next generation of research needs to get inside the black box of effective programs. Although the past decade has seen growth in the number of effectiveness and efficacy studies, we still found few studies that examine which specific program components drive effectiveness. Conducting comparative effectiveness studies would help to address this need. One barrier to expanding the knowledge base regarding the features that make early childhood programs effective is the high cost of conducting rigorous evaluations, such as randomized control trials. However, evidence from careful quasi-experimental designs would be better than having no evaluation evidence at all.

Early childhood programs improve a range of outcomes, so evaluations should collect outcomes across a range of domains. The findings from our synthesis demonstrate that programs that promote child development enhance multiple facets of individual well-being. Measuring only a subset of these facets of well-being is likely to miss some of the potential dividends that early childhood programs can pay across a lifetime.

Outcomes for two generations should be captured in early childhood program research. Ideally, program evaluations and economic evaluations of early childhood interventions should focus on outcomes for both participating children and their parents. Parents in particular can benefit from early childhood programs when they are the focus of the intervention, such as in parent education programs and many home visiting program models. Parents can also benefit in terms of greater labor force participation and higher earnings from ECE programs when the hours of care and early learning are sufficient to allow parents to increase their work hours, work experience, or education and training. BCAs that monetize parent outcomes allow programs to potentially reach a break-even point more quickly (because parental outcomes are often realized sooner than those for their children), account for benefits in a comprehensive way, and improve the comparability of BCAs.

There is a need for more studies that conduct longer-term follow-up to determine whether early program impacts are sustained. This review includes many more studies than our 2005 report, including many more BCAs. However, most of the newer studies follow study participants for short periods after program services end. Conducting more long-term studies should be a research priority. Making greater use of administrative data from the criminal justice system, social welfare programs, the child welfare system, and the unemployment insurance system is one lower-cost strategy for measuring longer-term outcomes for evaluation cohorts. Where longer-term follow-up is not feasible or too costly, researchers could make greater use of longitudinal studies that link outcomes in early childhood with outcomes later in childhood or adulthood. Research that establishes the causal relationship between outcomes in early childhood and outcomes in adulthood can be used to forecast the longer-term effects of early childhood programs and facilitate BCAs by linking measured outcomes to later outcomes that can be more readily valued in monetary terms.

Incentivizing cost data collection, as well as standardizing BCA methods, would facilitate comparisons across programs. The ability to compare BCA findings across early childhood programs is limited because of differences in the outcomes measured and the length of follow-up conducted for the program evaluation, the lack of cost data, and methodological differences in economic evaluation methods. Establishing a set of core outcomes to be measured in early childhood program evaluations (e.g., within any given domain in which a program is designed to produce effects), encouraging the routine collection of cost data, and incentivizing the use of standardized methods could boost the degree of comparability across economic evaluations. This will also provide policymakers with relevant, high-quality information to guide their decisionmaking in the years ahead.

Looking beyond these direct implications of our study for policy, practice, and research, we must also place our findings regarding early childhood interventions in the context of the broader literature around supports for healthy child development at any age. A range of researchers, including economists and psychologists, have argued that investing early can provide the highest payoff because skill development is cumulative. But without experiences and goods that support development in middle childhood and high school, the developmental foundations laid in early childhood are less likely to be fully capitalized on. Thus, whether targeted or universal, early childhood programs are just the foundational component of a continuum of effective supports for healthy development throughout childhood.

Note

The research described in this article was by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and conducted by RAND Labor and Population.

References

- Karoly Lynn A., Greenwood Peter W., Everingham Susan S. Sohler, Houbé Jill, Kilburn M. Rebecca, Rydell C. Peter, Sanders Matthew. and Chiesa James. Investing in Our Children: What We Know and Don't Know About the Costs and Benefits of Early Childhood Interventions. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR898.html MR-898-TCWF, 1998 As of September 12, 2017: [Google Scholar]

- Karoly Lynn A., Kilburn M. Rebecca. and Cannon Jill S. Early Childhood Interventions: Proven Results, Future Promise. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; 2005. https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG341.html MG-341-PNC. As of September 12, 2017: [Google Scholar]