Abstract

Chronic exposure to nicotine results in an upregulation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) at the cellular plasma membrane. nAChR upregulation occurs via nicotine-mediated pharmacological receptor chaperoning and is thought to contribute to the addictive properties of tobacco as well as relapse following smoking cessation. At the subcellular level, pharmacological chaperoning by nicotine and nicotinic ligands causes profound changes in the structure and function of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), ER exit sites, the Golgi apparatus and secretory vesicles of cells. Chaperoning-induced changes in cell physiology exert an overall inhibitory effect on the ER stress/unfolded protein response. Cell autonomous factors such as the repertoire of nAChR subtypes expressed by neurons and the pharmacological properties of nicotinic ligands (full or partial agonist versus competitive antagonist) govern the efficiency of receptor chaperoning and upregulation. Together, these findings are beginning to pave the way for developing pharmacological chaperones to treat Parkinson’s disease and nicotine addiction.

Keywords: Pharmacological chaperone, Chaperoning, Nicotine, nAChR, Tobacco, Neuroprotection, Parkinson’s disease, Neurodegeneration, Unfolded protein response, Dopaminergic, Endoplasmic reticulum stress, FRET, TIRF, Confocal, ER exit sites, Golgi, Ligand, COPII, COPI

1. Introduction

Pharmacological chaperoning has emerged as a potential strategy to treat diseases cystic fibrosis [1–3], Gaucher’s disease [4,5], nephrogenic diabetes insipidus [6], retinitis pigmentosa [7,8] and some cancers resulting from mutations in p53 [9]. Notably, the treatment of transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy with the pharmacological chaperone, tafamadis has been successful in a phase II/III clinical trial [10–13]. In these cases, ligand-mediated chaperoning corrects receptor mislocalization and/or prevents mutant proteins from forming toxic intracellular aggregates [14,15]. Pharmacological chaperoning has been employed to treat diseases associated with mutations in single genes [15], but the treatment of complex multifactorial disorders such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) or nicotine addiction with pharmacological chaperones remains challenging and will first require a mechanistic understanding of the cellular processes involved in chaperoning.

Here, we review our understanding of the cellular mechanisms by which nicotine and nicotinic ligands chaperone neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) and describe one way in which nAChR chaperoning can exert a neuroprotective effect in Parkinson’s disease (PD).

2. Chronic nicotine exposure upregulates nAChRs via pharmacological chaperoning

nAChR upregulation is defined as an increase in intracellular and/or plasma membrane receptors and likely underlies aspects of addiction to tobacco as well as relapse following smoking cessation. Since its discovery in the early 1980s [16–18], nAChR upregulation has become one of the best-studied consequences of chronic exposure to nicotine [19,20].

[3H]nicotine binding and PET imaging in tobacco users demonstrate upregulated nAChRs [21–28], suggesting a role in nicotine dependence. Because nAChRs upregulate in vitro, in vivo [16,17,22,25,29–32] and across a range of species (mice, rats, monkeys and humans), the cellular processes governing upregulation are likely to be cell autonomous and evolutionarily conserved. The process of upregulation involves post-translational rather than transcriptional changes in nAChR expression because nicotine exposure does not alter the mRNA levels of nAChR subunits [33]. Proposed mechanisms for upregulation include a decreased degradation of receptors [34], desensitization of surface receptors [35], nicotine acting as a maturational enhancer [36], a novel slow stabilizer [37] and a pharmacological chaperone [30,31,38,39]. Although the mechanisms for upregulation have been described in separate reports over a period of a decade or so, they are in fact part of the intracellular machinery that governs protein folding, transport and turnover. Thus, together these studies converge on the idea that the major cellular mechanism for nAChR upregulation is pharmacological chaperoning of intracellular receptors by nicotine and that upregulation is a complex process that involves changes at several levels of intracellular trafficking such as subunit assembly in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), export of assembled receptors from the ER, anterograde and retrograde vesicle transport and insertion of receptors into the plasma membrane [19,20].

Nicotine freely permeates the cellular plasma membrane and accumulates within intracellular organelles. As a result, nanomolar concentrations of nicotine are sufficient to alter the intracellular assembly and trafficking of nAChRs. The effects of nicotine on nAChR upregulation occur at nanomolar nicotine concentrations (~100–200nM) that are equivalent to the steady state nicotine concentration observed in chronic smokers [40–42]. Nanomolar concentrations of nicotine minimally activate surface nAChRs [39], indicating that nAChR upregulation is independent of second messenger signaling cascades triggered by channel activation and Ca2+ influx. Therefore, a likely mechanism for nAChR upregulation is pharmacological chaperoning, which is an intracellular process involving selective changes in receptor number, stoichiometry, trafficking between subcellular compartments and the ER associated degradation of receptors [20]. In agreement with this hypothesis, high-resolution quantitative methods (summarized in Fig. 1) developed to study intracellular nAChR biology reveal specific cellular processes that are selectively engaged by the cell during pharmacological chaperoning and nAChR upregulation. The next sections describe high-resolution imaging techniques and their contribution to our understanding of the pharmacological chaperoning of nAChRs.

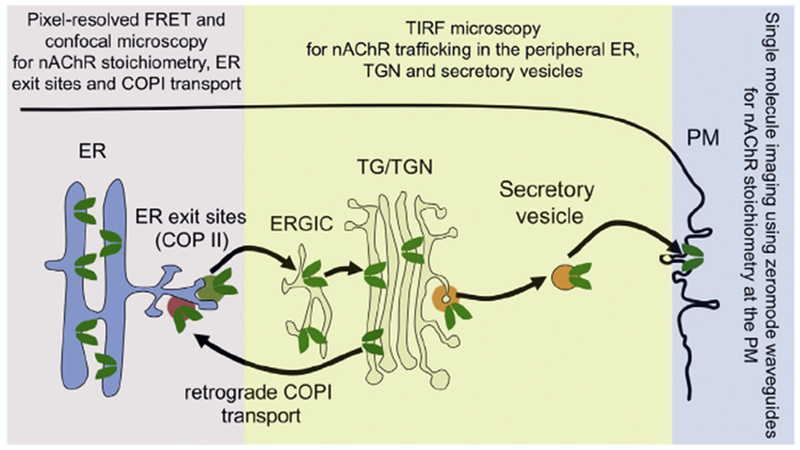

Fig. 1.

Methods to study pharmacological chaperoning of nAChRs. A schematic of nAChR trafficking in cells is shown. Pentameric receptors (green) assemble in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and concentrate in ER exit sites (dark green vesicle). Receptors then traffic to the trans Golgi network (TGN) via the ER to Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC). During chaperoning, ligand bound nAChRs return from the Golgi to the ER via COPI vesicles (orange-red) and are then cycled back to the Golgi via COPII vesicles. Some ligand bound receptors enter secretory vesicles bound to the plasma membrane (PM) from the TGN (yellow vesicle), resulting in upregulation at the PM. Also depicted are the methods that have been developed to study nAChR trafficking at each stage of the cellular secretory pathway. FRET and confocal microscopy allow high-resolution measurement of nAChR assembly and trafficking between the ER and Golgi. As explained in the text, under certain conditions, TIRF microscopy can be used to study nAChRs in the peripheral ER, TGN and upregulation at the PM. Single molecule imaging using zeromode waveguides allows measurement of nAChR stoichiometry of isolated receptors at the PM. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

2.1. Nicotine alters the stoichiometry of nAChRs in the endoplasmic reticulum: Förster’s resonance energy transfer

Förster’s resonance energy transfer (FRET) microscopy is an invaluable tool to study nanometer scale interactions of proteins within multimeric complexes [43]. FRET is based on the idea that following excitation of a fluorophore, energy can dissipate via the non-radiative dipole coupling of the excited fluorophore with a nearby non-excited fluorophore. Because FRET is inversely proportional to the 6th power of distance between fluorophores, occurrence of FRET indicates that the two proteins or molecules undergoing FRET are separated by only a few nanometers.

We developed a broadly applicable pixel-resolved FRET method to study receptor stoichiometry [44]. Our FRET studies show that cells expressing α4β2 nAChRs assemble pentameric receptors in two stoichiometries: (α4)2(β2)3 and (α4)3(β2)2. These two nAChR stoichiometries are present in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the Golgi apparatus and in the plasma membrane (PM) [31,39,44]. Following nicotine treatment, receptors in the ER and Golgi primarily show a (α4)2(β2)3 stoichiometry, indicating that nicotine stabilizes (α4)2(β2)3 receptors in the ER, prior to reaching the Golgi [31]. Thus, the process of nAChR upregulation is triggered within the ER and at a very early stage in the cellular secretory pathway.

2.2. Pharmacological chaperoning of nAChRs out of the ER: quantification of ER exit sites with confocal microscopy

Following the stabilization of (α4)2(β2)3 receptors in the ER, nicotine chaperones receptors from the ER to the plasma membrane. Export of receptors from the ER can be measured by quantification of specialized ER structures called ER exit sites (ERES), which concentrate cargo ready for export from the ER to the Golgi [31,39]. Visualization of ERES is achieved by tagging Sec24D, a component of COPII ERES vesicles with a fluorescent reporter tag and imaging with confocal microscopy.

In the absence of nicotine, the density of ERES observed in cells expressing nAChRs is directly proportional to the number of functional receptors at the cell surface [45], indicating that ERES density is a measure of active nAChR export from the ER and that the rate limiting step in nAChR trafficking through the secretory pathway is receptor export from the ER. Nicotine exposure causes a two-fold increase in the density of ERES, suggesting active nAChR chaperoning from the ER to the Golgi [31,39]. Because increases in the density of ERES are a direct measure of pharmacological chaperoning, this method can be broadly applied to measure the chaperoning efficacy of most pharmacological ligands. The process of ER export of nAChRs is critically dependent on the presence of an LXM (X = any amino acid) motif in the intracellular M3–M4 loop of nAChR subunits [31]. The LXM motif binds to Sec24D, which is an integral component of the COPII ERES vesicles. Thus, the presence or absence of LXM motifs in nAChR subunits partially determines the chaperoning efficiency of nicotine for particular nAChR subtypes, a phenomenon that has been observed in mouse as well as human nAChR subunits [31,46].

In addition to quantifying the ER exit of nAChRs with fluorescently tagged COPII vesicles, COPI vesicles tagged to fluorescent proteins can be used to quantify the retrograde transport of nAChRs from the Golgi apparatus back to the ER. COPI vesicles are involved in the trafficking of proteins from the Golgi apparatus to the PM (anterograde transport) [47–49], from the Golgi to the ER (retrograde transport) [49–51] as well as trafficking of proteins within the Golgi apparatus (intra-Golgi transport) [49,52]. Our recent study suggests that COPI-mediated retrograde transport of nAChRs from the Golgi to the ER appears to be specifically engaged during pharmacological chaperoning by nicotine and not under basal trafficking conditions [30]. These results have opened an exciting new avenue in which specific targeting of the COPI machinery can allow more precise manipulation of pharmacological chaperoning and nAChR upregulation in cells.

2.3. Pharmacological chaperoning alters near-PM nAChR dynamics and cellular architecture: total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy

Total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy illuminates ~200nm of the z-axis at the cellular periphery, thus allowing the visualization of molecules at the cellular plasma membrane (PM). Factors such as cell structure (polarized versus non-polarized cells), the type of protein labeling (quantum dots versus genetically encoded fluorescent tags) and the subcellular localization of labeled proteins can significantly alter the subcellular compartments visualized using TIRF. With TIRF imaging of fluorescent protein (FP)-tagged nicotinic receptors expressed in mouse neuroblastoma (Neuro-2a) cells, one visualizes multiple peripheral cellular compartments within the footprint of cells. In our studies using FP-tagged nAChRs, the subcellular structures visualized using TIRF include the peripheral ER, trans Golgi network (TGN)and the PM [53].

Pharmacological chaperoning by nicotine and nicotinic ligands increases the number of receptors at the PM by ~2-fold and significantly alters the architecture of the ER and trans Golgi network (TGN) [31,39]. Nicotine increases the density of peripheral ER and causes an elaboration of the TGN morphology, specifically an increase in the number and size of TGN vesicles [39]. Although the precise mechanism by which this occurs is not understood, it is clear that pharmacological chaperoning can profoundly alter the structure and function of entire organelles in the cellular secretory pathway.

TIRF microscopy has also been used in combination with nAChR subunits tagged to a pH sensitive fluorophore (superecliptic pHluorin or SEP). This allows the visualization of nAChR insertion events into the PM [30,32]. Studies with SEP-tagged nAChRs show that nicotine increases the insertion of vesicles containing nAChRs into the PM [30,32], indicating that nAChR upregulation is not due to a reduced turnover of receptors at the PM.

2.4. Nicotine chaperones nAChRs with a (α4)2(β2)3 stoichiometry to the plasma membrane: single molecule imaging using zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs)

Nicotine causes an intracellular redistribution of stoichiometry to (α4)2(β2)3 during the assembly of oligomeric receptors [31,39], however, a major challenge in determining shifts in receptor stoichiometry is to measure the stoichiometry of receptors at the plasma membrane (PM). One of the most effective means of accomplishing this is the use of single molecule spectroscopy to directly count fluorescently labeled subunits. While this has been accomplished in non-physiological expression systems such as oocytes, single molecule applications in live cells are hindered by poor spatial resolution and limited sensitivity due to cellular autofluorescence. Additionally, receptors tend to diffuse along the cell surface, which further complicates the isolation of individual receptors. A novel solution to observe single receptors on the cell membrane is to integrate live cells with zero mode waveguides (ZMWs). ZMWs consist of nanometer scale holes in thin metal films that can be used to isolate individual molecules from high concentration solutions. The application of ZMWs to live cells allows for the isolation of receptors by creating nanoscale observation ‘chambers’ on the plasma membrane. This imparts two primary advantages: (1) only molecules in the limited observation volume will be excited, suppressing background fluorescence, and (2) the nano-observation volume isolates membrane receptors for long periods of time allowing dynamics to be extracted. By transfecting cells with green fluorescent protein (eGFP) conjugated subunits, the receptors assemble such that each subunit is fluorescently labeled. By isolating a single receptor in the bottom of the nanoscale well and illuminating continuously, the eGFP tagged subunits can be bleached sequentially. This allows the bleaching steps of individual eGFP molecules to be counted as subunits and allows for the extraction of the stoichiometry of receptors. Measuring the stoichiometry at the plasma membrane allows us to observe the downstream effects of pharmacological chaperoning on the assembly of heteromeric nAChRs. This technique has been applied to determine the influence of nicotine on the stoichiometry of α4β2 nicotinic receptors [54]. It is clear that nicotine causes a PM upregulation of receptors with a (α4)2(β2)3 stoichiometry, while a partial nAChR agonist, cytisine, results in the insertion of (α4)3(β2)2 receptors at the PM [54]. The observed differences in stoichiometry indicate that chaperoning efficiency depends on the type of chemical chaperone and the subtypes of receptors that are being chaperoned. These factors are discussed below.

3. Factors influencing nAChR upregulation

nAChR upregulation and pharmacological chaperoning display tiers of selectivity at the level of brain regions and circuits, cell types (dopaminergic versus GABAergic neurons), subcellular organelles, receptor subtypes and the type of chaperone. Although each of the above factors can significantly influence nAChR chaperoning, we will focus on two cell autonomous factors: (i) nAChR subtypes and (ii) pharmacological properties of the chaperone.

3.1. nAChR subtypes

nAChRs are a non-homogenous population of ion channels consisting of α (α2 to α6) and β (β2 to β4) subunits arranged as heteromeric or homomeric receptor pentamers around a central non-specific cation conducting pore [55]. α7 and α4β2* nAChR subtypes (* indicates that other uncharacterized subunits may be present in the pentamer) are abundantly expressed throughout the CNS, while other nAChRs such as α6β2*, α3β4*, and α2β2 receptors show a more restricted localization pattern [55,56].

3.1.1. nAChR subtypes possess different ligand binding properties

nAChRs possess functional and ligand binding properties that are unique to the specific subtype. Thus, nicotine-induced chaperoning and upregulation can vary to a great extent due to differences in the ligand binding affinity of receptor subtypes. For example, high affinity α4β2* and α6β2β3* (* denotes an uncharacterized subunit in the receptor pentamer) nAChRs bind to nicotine with nanomolar affinity and therefore upregulate more readily at smoking-relevant nicotine concentrations (100–200 nM) [30,57] than the lower affinity a7 or α3β4 receptors that show an EC50 for nicotine upregulation in the micromolar range [58,59].

Conflicting reports for α6* nAChRs show upregulation, downregulation, or no change in response to chronic nicotine [60–62]. These discrepancies likely arise due to the presence or absence of accessory β3 subunits in α6β2* pentamers. β3 subunits can dramatically increase α6β2* receptor sensitivity to nicotine, resulting in upregulation at nanomolar concentrations [30]. Differential upregulation of nAChRs therefore appears to depend on the affinity of a particular receptor subtype to nicotine.

3.1.2. nAChR subtypes and trafficking motifs

The large intracellular loop between the receptor M3 and M4 transmembrane segments contains motifs that govern receptor trafficking out of the ER [30,31,46,63,64]. The loop also includes specialized sorting motifs that export receptors to either somatodendritic or axonal compartments of neurons [63]. The chaperoning and consequent upregulation of receptors is critically dependent on the specific combination of M3-M4 trafficking motifs present within a given receptor subtype [31,32,45,46]. LXM motifs (where X is any amino acid) in the M3-M4 loop of α4, α3 and β4 subunits govern the rate of ER exit of nAChRs, while RXRR motifs in the β2 subunits result in the ER retention of nAChRs [31]. α4β4 and α3β4 receptors contain LXM motifs on all five subunits do not upregulate significantly [31,58], presumably because these receptors already exit the ER with maximal efficiency in the absence of nicotine and nicotine chaperoning cannot significantly increase receptor trafficking through the secretory pathway. On the other hand, α4β2 nAChRs contain RXRR motifs in the β2 subunits that retain receptors in the ER [31]. In this case, nicotine binds to and chaperones nAChRs out of the ER, resulting in upregulation, while a majority of the receptors remain in the ER in the absence of nicotine.

A recently described trilysine motif (KKK) in the mouse β3 nAChR subunit binds to COPI vesicles and mediates the retrograde trafficking of nAChRs from the Golgi to the ER [30]. This process is exclusively engaged during nicotine-mediated upregulation of β3* receptors and not during the basal trafficking of receptors in the absence of nicotine. Interestingly, COPI mediated retrograde transport is also essential for the upregulation of α4β2 receptors and does not occur during nAChR trafficking in the absence of nicotine. Thus, pharmacological chaperoning likely involves the repeated cycling of receptors between the ER to the Golgi, which allows chaperones to induce the most stable conformation of nAChRs prior to the forward trafficking of receptors to the PM.

Based on these studies, it is clear that specific trafficking signals within receptor subtypes play a pivotal role in nAChR chaperoning. We will therefore consider known effects of chaperoning on nAChR subtypes. Fig. 2 summarizes the effect of chaperoning by nicotinic ligands on known nAChR subtypes.

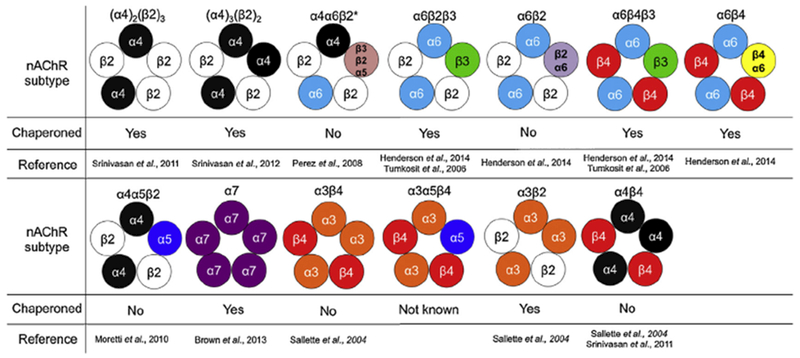

Fig. 2.

Pharmacological chaperoning of nAChR subtypes. The nAChR subtypes known to assemble in various brain regions is shown along with whether or not the particular subtype undergoes pharmacological chaperoning.

3.1.3. α4β2* nAChRs

Among the known CNS nAChR subtypes, α4β2* receptors are best characterized and most widely distributed across the CNS. It is clear that long-term nicotine administration in cell lines, cultured neurons, rodents, and humans results in the chaperoning of α4β2 nAChRs [16,17,22,25,29–32]. Chaperoning of α4β2* nAChRs occurs in cortex, midbrain, and hypothalamus, but not in thalamus or cerebellum [29,33,57,65–67]. α4β2* nAChR populations have recently found to be more complex and may exist with the addition of α5, α6, and/or β3 nAChR subunits [68,69]. Two populations of α4β2* nAChRs exist in the striatum: α4β2 and α4α5β2 subtypes [69]. The presence of an accessory α5 nAChR subunit alters chaperoning such that while α4β2 nAChRs are chaperoned by chronic nicotine, α4α5β2 nAChRs fail to undergo chaperoning [70,71]. This may be a consequence of subtle changes in the ligand binding affinity of α4α5β2 nAChRs when compared to α4β2 receptors [72,73].

Peng et al. [34] showed that one mechanism that may explain the increase of α4β2* nAChRs on the PM is a nicotine-induced decrease in the turnover of PM nAChRs. Despite this, others have shown that there is no change in the turnover of α4β2* nAChRs on the PM [37,74]. Several reports now point to nicotine-induced subunit maturation and assembly of α4β2* nAChRs in the ER as a primary mechanism for nAChR upregulation [19,31,36]. α4β2* nAChRs assemble rather inefficiently and it is likely that nicotine increases the assembly and stability of pentamers in the ER, thereby allowing mature and stable pentamers to efficiently traffic through the secretory pathway.

3.1.4. α6* nAChRs

Characterizing the chaperoning of α6* nAChRs has been more tedious than α4β2 nAChRs, mainly due to the poor expression of α6* nAChRs in heterologous systems. Many studies in mice suggest that α6p2* nAChRs are not chaperoned by nicotine [66,71,75–77], but other studies have observed chaperoning of α6* nAChRs following chronic nicotine treatment [30,60]. Yet other, assays in cultured cells expressing α6* nAChRs, show that both α6β2 and α6β2β3 nAChRs are chaperoned following chronic nicotine treatment [61,62]. Perez et al. [60] showed that α6β2* nAChRs that did not contain α4 nAChR subunits are chaperoned by nicotine, while α6α4β2* nAChRs do not undergo chaperoning. These discrepancies likely arise due to differences in expression systems, assays and/or exposure paradigms to the chaperoning ligand.

We have shown that in vitro, the upregulation of α6β2β3 nAChRs occurs via an increased insertion of receptors into the PM [30]. Using a pH sensitive eGFP analog (supercliptic pHluorin [SEP]) we found that there is an increase in the number of α6* nAChRs inserted on the PM following chronic nicotine treatment. We also found that the fold increase in insertion to the PM is directly proportional to the increase in nAChR density on the PM. Therefore it is possible that the upregulation of α6* nAChRs is principally due to an increased insertion of new receptors rather than a change in the stability or turnover of pre-existing receptors at the PM. Furthermore, we found that both α6β2* and α6β4* nAChRs are chaperoned by nicotine and α6β2* nAChRs chaperone only in the presence of β3 subunits, while α6β4 nAChRs are chaperoned with and without the β3 nAChR subunit [30]. As described earlier, chaperoning in this case, appears to be dependent on the presence of a trilysine motif in the M3-M4 loop of p3 subunits. The trilysine motif binds to COPI components and mediates the retrograde transport of receptors from the ER to the Golgi [30].

3.1.5. α3* nAChRs

α3* (α3β4, α3α5β4) nAChRs are primarily located in the peripheral nervous system. In the CNS, α3* nAChRs are found in the thalamus, hypothalamus, locus coeruleus, and habenula [78]. α3β4 nAChRs generally do not upregulate easily and require much higher concentrations than that found in a smoker’s brain [58]. This is likely due to the fact that β4* nAChRs are exported from the ER to the PM very efficiently [31,32]. It is known that α3 and β4 nAChR subunits have an ER export motif [31,46], but lack an ER retention motif found in β2 nAChR subunits [31]. Therefore α3β4 nAChRs may be expressed on the PM at densities where no further upregulation is possible.

In vitro, α3β2 nAChRs have been shown to upregulate in response to chronic nicotine [61]. This was shown to occur at nicotine concentrations much higher than that typically found in a smoker’s brain (>1 μM). The fact that α3β2 nAChRs upregulate while α3β4 receptors are not upregulated by nicotine agrees with the idea that the LXM ER export signals in β4 nAChR subunits produce a ‘chaperone’ like effect in the absence of nicotine. In contrast, the β2 nAChR subunit is normally retained in the ER because of the presence of an ER retention motif in the M3–M4 loop and is therefore available to bind to and be chaperoned by nicotine and nicotinic ligands.

3.1.6. Chaperoning of α7 nAChRs

α7 nAChRs are another subtype found distributed in the CNS. α7 nAChRs are found in the spinal cord, amygdala, olfactory region, cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum, and hypothalamus [78]. Typically, mRNA levels of nAChRs are unaffected by chronic nicotine and have led to the understanding that nAChR upregulation occurs through posttranscriptional mechanisms [19,20,79]. Despite this, Lam et al. [80] showed that chronic nicotine treatment increased mRNA levels of α7 nAChRs. This increase by transcriptional mechanisms was mediated through the S1-GATA2 pathway. More recently, upregulation of α7 nAChRs (and their mRNA levels) has been shown to occur through recruitment of Sp1-GATA4 or Sp1-GATA6 [81]. This upregulation occurs at concentrations of nicotine (100 nM) that are physiologically relevant to human smokers.

3.2. Factors influencing upregulation: chaperone-specific properties

An efficient pharmacological chaperone must: (i) be able to access the compartment in which the target protein exists, which in the case of nAChRs is the ER and (ii) display a high affinity for binding to the target protein.

3.2.1. Chaperone accumulation in intracellular organelles

Nicotine is an exemplar pharmacological chaperone that, in the free base form, easily penetrates the plasma membrane. Positively charged quaternary ammonium compounds such as the agonist, acetylcholine (ACh) or peptides such as α-Conotoxin MII and α-bungarotoxin cannot permeate the plasma membrane and will not reach intracellular nAChR targets, which makes these molecules inefficient pharmacological chaperones.

3.2.2. Chaperone affinity

Within seconds of inhaling cigarette smoke, nicotine rapidly enters the bloodstream, passes the blood brain barrier and achieves micromolar concentrations in the brain, however, in chronic smokers, the steady state concentration of nicotine is ~100–200nM [40–42]. These chronic concentrations of nicotine are well within the range required to upregulate high-sensitivity α4β2* and α6β2β3* nAChRs. Unlike acetylcholine, nanomolar nicotine concentrations are not rapidly cleared from cells, allowing the drug to interact with intracellular nAChRs over a period of minutes, hours and even days. Because of this prolonged exposure to nAChRs, nicotine can bind to and stabilize multiple states of nAChRs, including the open, closed and desensitized receptor conformations, but a deeply desensitized nAChR conformation is likely favored. Because of a restricted binding capability, nAChR antagonists such as dihydro-beta-erythroidine (D^E) and non-competitive antagonists such as the open channel blocker, mecamylamine will stabilize only a small subset of open, closed or desensitized receptor conformations. As a result, these compounds chaperone nAChRs at ~10–100-fold greater concentrations than nicotine [34,82].

The efficiency of pharmacological chaperoning of nAChRs is therefore determined by a combination of the ability of chaperones to accumulate in intracellular compartments and binding kinetics to nAChRs. Generally, membrane-permeable agonists and partial agonists are likely to be more efficient nAChR chaperones than competitive or non-competitive antagonists.

4. Pharmacological chaperoning of nAChRs as a therapeutic strategy for Parkinson’s disease

We described nicotine as a pharmacological chaperone of nAChRs and detailed the influence of receptor-specific and chaperone-specific factors on pharmacological chaperoning. We will now explain how pharmacological chaperoning by nicotine can serve a neuroprotective function in Parkinson’s disease (PD).

4.1. Tobacco and nicotine prevent Parkinson’s disease

Epidemiological studies over the past 50 years show a strong inverse correlation between a person’s history of tobacco use and his/her risk for PD [83–86]. The neuroprotective effects of tobacco are independent of genetic background, because in retrospective studies with identical twins that are discordant for smoking, PD occurs in the non-smoking twin [84]. The neuroprotective effect of tobacco persists in studies utilizing age-matched controls of nontobacco users [85], ruling out spurious effects due to early mortality following the use of tobacco.

Nicotine, the active addictive ingredient of tobacco likely mediates neuroprotection because: (i) nicotine exposure prevents neuronal cell death in vivo [86–89], (ii) clinical trials with nicotine patches show an attenuation of PD symptoms [90–93], (iii) nicotine binds to nAChRs at smoking-relevant concentrations (~100–200 nM) and nAChRs are abundantly expressed in the dopaminergic (DA) neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) that are lost in PD [68] and (iv) nicotine neuroprotection is lost in nAChR knockout mice [89]. Thus, it is likely that the neuroproective effects of tobacco specifically proceed via interaction(s) between nicotine and nAChRs.

4.2. “Outside-in” versus “inside-out” mechanisms of neuroprotection

Although the neuroprotective effects of nicotine are well documented, the molecular mechanism(s) by which this occurs remain unclear. Some studies hypothesize an “outside-in” mechanism for neuroprotection in which nicotine activates surface nAChRs, resulting in Ca2+ influx and transcriptional changes [94–97].

Nicotine can also exert neuroprotection via “inside-out” pharmacology [19,98]. In this model, nicotine concentrates within intracellular compartments and chaperones nAChRs out of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [20,98]. Nicotine-induced nAChR chaperoning can alter the physiology of the ER and the ER stress/unfolded protein response (UPR), resulting in transcriptional changes and neuroprotection [39,98]. Although not yet systematically studied, it may well be that both mechanisms act in concert to exert a net neuroprotective effect on the cell, but we will focus on the “inside-out” hypothesis of nicotine neuroprotection.

4.3. The ER stress response and neurodegeneration

The ER stress/unfolded protein response (UPR) is a multi-armed signaling cascade triggered by the presence of misfolded proteins, excess Ca2+ or oxidative stress in the ER. Following activation by these stressors, the three ER resident sensors, activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), inositol requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) and protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) initiate complex cell signaling cascades culminating in transcriptional changes within the nucleus. A detailed description of the UPR is outside the scope of this review and is described elsewhere [99–101]. Importantly, the UPR has emerged as a major causative factor in the development of several neurodegenerative disorders, including Parkinson’s disease (PD). The dopaminergic (DA) neurons that are lost in PD are under continuous ER stress due to the presence of reactive oxygen species from toxic metabolites of dopamine and cyclical Ca2+ influx. Indeed, ER stress markers are activated in the SNc of PD patients and generally during neurodegeneration indicating that the ER stress/unfolded protein response is a causative factor for neurodegeneration and PD [102–106].

4.4. Pharmacological chaperoning inhibits the ER stress response

Our studies show that nicotine inhibits the PERK and ATF6 ER stress pathways via pharmacological chaperoning [39] and that inhibition of ER stress occurs in cultured dopaminergic neurons expressing native nAChRs (unpublished). Because pharmacological chaperoning involves profound changes in cellular physiology such as an increased export of cargo from the ER and increases in the size and/or elaboration of subcellular organelles such as the ER and Golgi one can hypothesize that nicotine generally increases the efficiency by which dopaminergic neurons export cargo from the ER via ER exit sites, thus reducing the protein burden and increasing efficiency. In addition, an increased ER size due to chaperoning can enable more efficient Ca2+ buffering, thereby improving the overall health of dopaminergic neurons and preventing their death. It may well be that techniques used to measure chaperoning can become useful drug discovery tools for identifying neuroprotective compounds against PD.

4.5. Genetic mutations in PD and pharmacological chaperoning

Studies show that the overexpression of α-synuclein [107], mutations in leucine rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) [108] or mutations in the α-synuclein gene [109–112] can result in PD. In these cases, dopaminergic cell death occurs due to a dysfunction in the cellular trafficking machinery and processing of α-synuclein. Specifically, dysfunction in the export or endosomal/lysosomal processing of α-synuclein have been implicated in PD pathogenesis [113]. Pharmacological chaperoning of nAChRs can potentially affect α-synuclein trafficking by: (i) increasing the formation of ER export sites, which can counter the lack of forward trafficking of α-synuclein and attenuate the disease process, (ii) increasing the formation of COPI-containing vesicles, which can influence the number as well as the efficiency by which early and late endosomes are formed in dopaminergic neurons and (iii) influencing the biology of lysosomes in dopaminergic neurons by increasing the number of nicotine-bound nAChRs that are resistant to degradation and therefore possess a longer intracellular half life.

Another important area of research is the role of mitochondrial dysfunction in PD. Mutations in mitochondrial proteins such as Parkin may account for as much as 5% of PD cases [114]. These mutations likely result in mitochondrial dysfunction, mitophagy and the consequent depletion of energy stores in dopaminergic neurons, thus causing cell death and PD [115,116]. Research indicates that the ER stress response is accompanied by a similar response in the mitochondria known as the mitochondrial stress or mitochondrial unfolded protein response [117]. One can speculate that the inhibitory effect of nAChR chaperoning on ER stress can directly or indirectly influence mitochondrial stress and dysfunction via as yet undiscovered mechanisms. Further research is required to understand the interplay between the mitochondrial the ER stress response in the context of neurodegeneration.

4.6. Can pharmacological chaperoning be broadly applied to neurodegeneration?

Since ER stress plays a role in the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s diease (PD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Huntington’s disease (HD) and prion-related degeneration [102], it is tempting to speculate that inhibition of the ER stress response by nicotine can be neuroprotective in the broader context of neurodegeneration.

If nicotine inhibits ER stress via pharmacological chaperoning of nAChRs, one might expect a nicotine-mediated neuroprotective effect on any CNS neuron with natively expressed nAChRs. Conceptually, when one applies the inhibition of ER stress by nicotine-induced pharmacological chaperoning as a general treatment strategy for neurodegeneration, factors such as the subtype of expressed nAChRs, the absolute number of nAChRs expressed per neuron and the context of neuronal degeneration (genetic versus environmental) likely play a decisive role on whether or not nicotine is neuroprotective. It may well be that the SNc dopaminergic neurons degenerating in PD possess a combination of nAChR subtypes and native receptor expression levels that are readily chaperoned by nicotine. Clearly, more work needs to be done to understand if and how nicotine can exert a neuroprotective effect in other forms of neurodegeneration.

5. Perspectives and future directions

nAChR chaperoning is a complex process involving changes at almost every step of the cellular secretory pathway. Cell autonomous factors such as expressed nAChR subtypes and the properties of the ligand can exert a profound influence on the pharmacological chaperoning of nAChRs.

Although high-resolution imaging techniques have shed light on the cellular mechanism of pharmacological chaperoning by nicotine, several questions remain to be answered: (i) a major future challenge is to study pharmacological chaperoning in vivo. This is an important step in order to understand the physiological relevance of chaperoning for nicotine addiction and in the context of neuroprotection against PD. In vivo studies will require the development of imaging techniques and biological tools, including transgenic mice to study nAChR chaperoning in areas of the brain that are currently difficult to access using standard methods. (ii) Understanding the molecular mechanisms by which chaperoning reduces ER stress in dopaminergic neurons is critical for the development of therapeutics against PD and possibly other neurodegenerative disorders.

Acknowledgements

Supported by grants from the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP 18FT-0066), the Michael J Fox Foundation (MJFF), U.S. National Institutes of Health, Louis and Janet Fletcher.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- [1].Chanoux RA, Rubenstein RC. Molecular chaperones as targets to circumvent the cftr defect in cystic fibrosis. Front Pharmacol 2012;3:137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wang Y, Loo TW, Bartlett MC, Clarke DM. Modulating the folding of p-glycoprotein and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator truncation mutants with pharmacological chaperones. Mol Pharmacol 2007;71:751–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wang Y, Loo TW, Bartlett MC, Clarke DM. Additive effect of multiple pharmacological chaperones on maturation of CFTR processing mutants. Biochem J 2007;406:257–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sawkar AR, Cheng WC, Beutler E, Wong CH, Balch WE, Kelly JW. Chemical chaperones increase the cellular activity of n370s beta-glucosidase: a therapeutic strategy for gaucher disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:15428–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sawkar AR, Adamski-Werner SL, Cheng WC, Wong CH, Beutler E, Zimmer KP, et al. Gaucher disease-associated glucocerebrosidases show mutation-dependent chemical chaperoning profiles. Chem Biol 2005;12:1235–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tamarappoo BK, Verkman AS. Defective aquaporin-2 trafficking in nephrogenic diabetes insipidus and correction by chemical chaperones. J Clin Invest 1998;101:2257–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Noorwez SM, Kuksa V, Imanishi Y, Zhu L, Filipek S, Palczewski K, et al. Pharmacological chaperone-mediated in vivo folding and stabilization of the p23h-opsin mutant associated with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. J Biol Chem 2003;278:14442–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kosmaoglou M, Schwarz N, Bett JS, Cheetham ME. Molecular chaperones and photoreceptor function. Prog Retin Eye Res 2008;27:434–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Foster BA, Coffey HA, Morin MJ, Rastinejad F. Pharmacological rescue of mutant p53 conformation and function. Science 1999;286:2507–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Razavi H, Palaninathan SK, Powers ET, Wiseman RL, Purkey HE, Mohamed-mohaideen NN, et al. Benzoxazoles as transthyretin amyloid fibril inhibitors: synthesis, evaluation, and mechanism of action. Angew Chem 2003;42:2758–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Johnson SM, Connelly S, Fearns C, Powers ET, Kelly JW. The transthyretin amyloidoses: from delineating the molecular mechanism of aggregation linked to pathology to a regulatory-agency-approved drug. J Mol Biol 2012;421:185–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Coelho T, Maia LF, Martins da Silva A, Waddington Cruz M, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Lozeron P, et al. Tafamidis for transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurology 2012;79:785–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Coelho T, Maia LF, da Silva AM, Cruz MW, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Suhr OB, et al. Long-term effects of tafamidis for the treatment of transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Neurol 2013;260:2802–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chaudhuri TK, Paul S. Protein-misfolding diseases and chaperone-based therapeutic approaches. FEBS J 2006;273:1331–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Loo TW, Clarke DM. Chemical and pharmacological chaperones as new therapeutic agents. Expert Rev Mol Med 2007;9:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Schwartz RD, Kellar KJ. Nicotinic cholinergic receptor binding sites in the brain: regulation in vivo. Science 1983;220:214–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Marks MJ, Burch JB, Collins AC. Effects of chronic nicotine infusion on tolerance development and nicotinic receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1983;226:817–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Marks MJ, Stitzel JA, Collins AC. Time course study of the effects of chronic nicotine infusion on drug response and brain receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1985;235:619–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lester HA, Xiao C, Srinivasan R, Son CD, Miwa J, Pantoja R, et al. Nicotine is a selective pharmacological chaperone of acetylcholine receptor number and stoichiometry. Implications for drug discovery. AAPS J 2009;11:167–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Miwa JM, Freedman R, Lester HA. Neural systems governed by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: emerging hypotheses. Neuron 2011;70:20–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Benwell ME, Balfour DJ, Anderson JM. Evidence that tobacco smoking increases the density of(−)-[3H]nicotine binding sites in human brain. J Neurochem 1988;50:1243–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Breese CR, Adams C, Logel J, Drebing C, Rollins Y, Barnhart M, et al. Comparison of the regional expression of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 mRNA and [125i]-α-bungarotoxin binding in human postmortem brain. J Comp Neurol 1997;387:385–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Brody AL, Mukhin AG, La Charite J, Ta K, Farahi J, Sugar CA, et al. Up-regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in menthol cigarette smokers. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2013;16:957–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Staley JK, Krishnan-Sarin S, Cosgrove KP, Krantzler E, Frohlich E, Perry E, et al. Human tobacco smokers in early abstinence have higher levels of β2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors than nonsmokers. J Neurosci 2006;26:8707–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mamede M, Ishizu K, Ueda M, Mukai T, Iida Y, Kawashima H, et al. Temporal change in human nicotinic acetylcholine receptor after smoking cessation: 5ia SPECT study. J Nucl Med 2007;48:1829–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wullner U, Gundisch D, Herzog H, Minnerop M, Joe A, Warnecke M, et al. Smoking upregulates α4β2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the human brain. Neurosci Lett 2008;430:34–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cosgrove KP, Batis J, Bois F, Maciejewski PK, Esterlis I, Kloczynski T, et al. Beta2-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor availability during acute and prolonged abstinence from tobacco smoking. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009;66:666–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Perry DC, Davila-Garcia MI, Stockmeier CA, Kellar KJ. Increased nicotinic receptors in brains from smokers: membrane binding and autoradiography studies. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1999;289:1545–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Nashmi R, Xiao C, Deshpande P, McKinney S, Grady SR, Whiteaker P, et al. Chronic nicotine cell specifically upregulates functional α4* nicotinic receptors: basis for both tolerance in midbrain and enhanced long-term potentiation in perforant path. J Neurosci 2007;27:8202–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Henderson BJ, Srinivasan R, Nichols WA, Dilworth CN, Gutierrez DF, Mackey EDW, et al. Nicotine exploits a COPI-mediated process for chaperone-mediate up-regulation of its receptors. J Gen Physiol 2014;143(1):51–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Srinivasan R, Pantoja R, Moss FJ, Mackey ED, Son CD, Miwa J, et al. Nicotine up-regulates α4β2 nicotinic receptors and ER exit sites via stoichiometry-dependent chaperoning. J Gen Physiol 2011;137:59–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Richards CI, Srinivasan R, Xiao C, Mackey ED, Miwa JM, Lester HA. Trafficking of α4* nicotinic receptors revealed by superecliptic phluorin: effects of a β4 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated mutation and chronic exposure to nicotine. J Biol Chem 2011;286:31241–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Marks MJ, Pauly JR, Gross SD, Deneris ES, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Heinemann SF, et al. Nicotine binding and nicotinic receptor subunit rna after chronic nicotine treatment. J Neurosci 1992;12:2765–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Peng X, Gerzanich V, Anand R, Whiting PJ, Lindstrom J. Nicotine-induced increase in neuronal nicotinic receptors results from a decrease in the rate of receptor turnover. Mol Pharmacol 1994;46:523–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Fenster CP, Whitworth TL, Sheffield EB, Quick MW, Lester RA. Upregulation of surface a4b2 nicotinic receptors is initiated by receptor desensitization after chronic exposure to nicotine. J Neurosci 1999;19:4804–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sallette J, Pons S, Devillers-Thiery A, Soudant M, Prado de Carvalho L, Changeux JP. Nicotine upregulates its own receptors through enhanced intracellular maturation. Neuron 2005;46:595–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Vallejo YF, Buisson B, Bertrand D, Green WN. Chronic nicotine exposure upregulates nicotinic receptors by a novel mechanism. J Neurosci 2005;25:5563–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kuryatov A, Luo J, Cooper J, Lindstrom J. Nicotine acts as a pharmacological chaperone to up-regulate human α4β2 acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol 2005;68:1839–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Srinivasan R, Richards CI, Xiao C, Rhee D, Pantoja R, Dougherty DA et al. Pharmacological chaperoning of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors reduces the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Mol Pharmacol 2012;81:759–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Benowitz NL, Porchet H, Jacob P 3rd Nicotine dependence and tolerance in man: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic investigations. Prog Brain Res 1989;79:279–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hukkanen J, Jacob P 3rd, Benowitz NL. Metabolism and disposition kinetics of nicotine. Pharmacol Rev 2005;57:79–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Matta SG, Balfour DJ, Benowitz NL, Boyd RT, Buccafusco JJ, Caggiula AR, et al. Guidelines on nicotine dose selection for in vivo research. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;190:269–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Pollok BA, Heim R. Using gfp in fret-based applications. Trends Cell Biol 1999;9:57–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Srinivasan R, Richards CI, Dilworth C, Moss FJ, Dougherty DA, Lester HA. Forster resonance energy transfer (fret) correlates of altered subunit stoichiometry in cys-loop receptors, exemplified by nicotinic α4β2. Int J Mol Sci 2012;13:10022–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Xiao C, Srinivasan R, Drenan RM, Mackey ED, McIntosh JM, Lester HA. Characterizing functional α6β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in vitro: mutant beta2 subunits improve membrane expression, and fluorescent proteins reveal responsive cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2011;82:852–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Mazzo F, Pistillo F, Grazioso G, Clementi F, Borgese N, Gotti C, et al. Nicotine-modulated subunit stoichiometry affects stability and trafficking of α3β4 nicotinic receptor. J Neurosci 2013;33:12316–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Balch WE, Glick BS, Rothman JE. Sequential intermediates in the pathway of intercompartmental transport in a cell-free system. Cell 1984;39:525–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Rothman JE, Wieland FT. Protein sorting by transport vesicles. Science 1996;272:227–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Rothman JE. The future of Golgi research. Mol Biol Cell 2010;21:3776–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Letourneur F, Gaynor EC, Hennecke S, Demolliere C, Duden R, Emr SD, et al. Coatomer is essential for retrieval of dilysine-tagged proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 1994;79:1199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Orci L, Stamnes M, Ravazzola M, Amherdt M, Perrelet A, Sollner TH, et al. Bidirectional transport by distinct populations of copi-coated vesicles. Cell 1997;90:335–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Pellett PA, Dietrich F, Bewersdorf J, Rothman JE, Lavieu G. Inter-Golgi transport mediated by copi-containing vesicles carrying small cargoes. eLife 2013;2:e01296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Fish KN. Total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. Curr Protoc Cytom 2009. Chapter 12:Unit12 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Richards CI, Luong K, Srinivasan R, Turner SW, Dougherty DA, Korlach J, et al. Live-cell imaging of single receptor composition using zero-mode waveguide nanostructures. Nano Lett 2012;12:3690–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Gotti C, Moretti M, Gaimarri A, Zanardi A, Clementi F, Zoli M. Heterogeneity and complexity of native brain nicotinic receptors. Biochem Pharmacol 2007;74:1102–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Gotti C, Zoli M, Clementi F. Brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: native subtypes and their relevance. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2006;27:482–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Nguyen HN, Rasmussen BA, Perry DC. Subtype-selective up-regulation by chronic nicotine of high-affinity nicotinic receptors in rat brain demonstrated by receptor autoradiography. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2003;307:1090–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Peng X, Gerzanich V, Anand R, Wang F, Lindstrom J. Chronic nicotinetreatment up-regulates α3 and α7 acetylcholine receptor subtypes expressed by the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y. Mol Pharmacol 1997;51:776–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Nuutinen S, Ekokoski E, Lahdensuo E, Tuominen RK. Nicotine-induced upregulation of human neuronal nicotinic α7-receptors is potentiated by modulation of camp and pkc in SH-EP1-Hα7 cells. Eur J Pharmacol 2006;544:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Perez XA, Bordia T, McIntosh JM, Grady SR, Quik M. Long-term nicotine treatment differentially regulates striatal α6α4β2* and α6(nonα4)β2* nachr expression and function. Mol Pharmacol 2008;74:844–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Walsh H, Govind AP, Mastro R, Hoda JC, Bertrand D, Vallejo Y, et al. Upregulation of nicotinic receptors by nicotine varies with receptor subtype. J Biol Chem 2008;283:6022–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Tumkosit P, Kuryatov A, Luo J, Lindstrom J. B3 subunits promote expression and nicotine-induced up-regulation of human nicotinic α6* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed in transfected cell lines. Mol Pharmacol 2006;70:1358–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Xu J, Zhu Y, Heinemann SF. Identification of sequence motifs that target neuronal nicotinic receptors to dendrites and axons. J Neurosci 2006;26:9780–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kracun S, Harkness PC, Gibb AJ, Millar NS. Influence of the M3-M4 intracellular domain upon nicotinic acetylcholine receptor assembly, targeting and function. Br J Pharmacol 2008;153:1474–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Pauly JR, Marks MJ, Gross SD, Collins AC. An autoradiographic analysis of cholinergic receptors in mouse brain after chronic nicotinetreatment. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1991;258:1127–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Perry DC, Mao D, Gold AB, Mclntosh JM, Pezzullo JC, Kellar KJ. Chronic nicotine differentially regulates α6- and β3-containing nicotinic cholinergic receptors in rat brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2007;322:306–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Doura MB, Gold AB, Keller AB, Perry DC. Adult and periadolescent rats differ in expression of nicotinic cholinergic receptor subtypes and in the response of these subtypes to chronic nicotine exposure. Brain Res 2008;1215: 40–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Champtiaux N, Gotti C, Cordero-Erausquin M, David DJ, Przybylski C, Lena C, et al. Subunit composition of functional nicotinic receptors in dopaminergic neurons investigated with knock-out mice. J Neurosci 2003;23: 7820–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Grady SR, Salminen O, McIntosh JM, Marks MJ, Collins AC. Mouse striatal dopamine nerve terminals express alpha4alpha5beta2 and two stoichiometric forms of α4β2*-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Mol Neurosci 2010;40:91–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Mao D, Perry DC, Yasuda RP, Wolfe BB, Kellar KJ. The alpha4beta2alpha5 nicotinic cholinergic receptor in rat brain is resistant to up-regulation by nicotine in vivo. J Neurochem 2008;104:446–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Moretti M, Mugnaini M, Tessari M, Zoli M, Gaimarri A, Manfredi I, et al. A comparative study of the effects of the intravenous self-administration or subcutaneous minipump infusion of nicotine on the expression of brain neuronal nicotinic receptor subtypes. Mol Pharmacol 2010;78:287–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Wageman CR, Marks MJ, Grady SR. Effectiveness of nicotinic agonists as desensitizers at presynaptic α4β2- and α4α5β2-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Nicotine Tobacco Res 2013;16(3):297–305, 10.1093/ntr/ntt146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Chatterjee S, Santos N, Holgate J, Haass-Koffler CL, Hopf FW, Kharazia V, et al. α5 subunit regulates the expression and function of α4*-containing neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the ventral-tegmental area. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e68300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Darsow T, Booker TK, Pina-Crespo JC, Heinemann SF. Exocytic trafficking is required for nicotine-induced up-regulation of α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Biol Chem 2005;280:18311–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].McCallum SE, Parameswara N, Bordia T, Fan H, McIntosh JM, Quik M. Differential regulation of mesolimbic α3*/α6*β2 and α4*β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor sites and function after long-term oral nicotine to monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2006;318:381–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].McCallum SE, Parameswaran N, Bordia T, Fa H, Tyndale RF, Langston JW, et al. Increases in α4* but not α3*/α6* nicotinic receptor sites and function in the primate striatum following chronic oral nicotine treatment. J Neurochem 2006;96:1028–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Mugnaini M, Garzotti M, Sartori I, Pilla M, Repeto P, Heidbreder CA, et al. Selective down-regulation of[(125)I]y0-α-conotoxin mii binding in rat mesostriatal dopamine pathway following continuous infusion of nicotine. Neuroscience 2006;137:565–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Jensen AA, Frolund B, Liljefors T, Krogsgaard-Larsen P. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: structural revelations, target identifications, and therapeutic inspirations. J Med Chem 2005;48:4705–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Albuquerque EX, Pereira EF, Alkondon M, Rogers SW. Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev 2009;89:73–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Lam DC, Girard L, Ramirez R, Chau WS, Suen WS, Sheridan S, et al. Expression of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit genes in non-small-cell lung cancer reveals differences between smokers and nonsmokers. Cancer Res 2007;67:4638–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Brown KC, Perry HE, Lau JK, Jones DV, Pulliam JF, Thornhill BA, et al. Nicotine induces the up-regulation of the α7-nicotinic receptor (α7-nAChR) in human squamous cell lung cancer cells via the sp1/gata protein pathway. J Biol Chem 2013;288:33049–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Gopalakrishnan M, Molinari EJ, Sullivan JP. Regulation of human α4β2 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by cholinergic channel ligands and second messenger pathways. Mol Pharmacol 1997;52:524–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Hernan MA, Takkouche B, Caamano-Isorna F, Gestal-Otero JJ. A meta-analysis of coffee drinking, cigarette smoking, and the risk of Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 2002;52:276–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Tanner CM, Goldman SM, Aston DA, Ottman R, Ellenberg J, Mayeux R, et al. Smoking and parkinson’s disease in twins. Neurology 2002;58: 581–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Ritz B, Ascherio A, Checkoway H, Marder KS, Nelson LM, Rocca WA, et al. Pooled analysis of tobacco use and risk of parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 2007;64:990–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Quik M, Wonnacott S. α6β2* and α4β2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as drug targets for Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacol Rev 2011;63: 938–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Maggio R, Riva M, Vaglini F, Fornai F, Molteni R, Armogida M, et al. Nicotine prevents experimental Parkinsonism in rodents and induces striatal increase of neurotrophic factors. J Neurochem 1998;71:2439–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Costa G, Abin-Carriquiry JA, Dajas F. Nicotine prevents striatal dopamine loss produced by 6-hydroxydopamine lesion in the substantia nigra. Brain Res 2001;888:336–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Ryan RE, Ross SA, Drago J, Loiacono RE. Dose-related neuroprotective effects of chronic nicotine in 6-hydroxydopamine treated rats, and loss of neuroprotection in a4 nicotinic receptor subunit knockout mice. BrJ Pharmacol 2001;132:1650–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Fagerstrom KO, Pomerleau O, Giordani B, Stelson F. Nicotine may relieve symptoms of parkinson’s disease. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;116:117–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Kelton MC, Kahn HJ, Conrath CL, Newhouse PA. The effects of nicotine on Parkinson’s disease. Brain Cogn 2000;43:274–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Mitsuoka T, Kaseda Y, Yamashita H, Kohriyama T, Kawakami H, Nakamura S, et al. Effects of nicotine chewing gum on updrs score and p300 in early-onset Parkinsonism. Hiroshima J Med Sci 2002;51:33–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Villafane G, Cesaro P, Rialland A, Baloul S, Azimi S, Bourdet C, et al. Chronic high dose transdermal nicotine in parkinson’s disease: an open trial. Eur J Neurol 2007;14:1313–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Belluardo N, Mudo G, Blum M, Cheng Q, Caniglia G, Dell’Albani P, et al. The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist (+/−)-epibatidine increases fgf-2 mRNA and protein levels in the rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 1999;74:98–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Dajas-Bailador FA, Lima PA, The Wonnacott S. α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtype mediates nicotine protection against nmda excitotoxicity in primary hippocampal cultures through a Ca(2+) dependent mechanism. Neuropharmacology 2000;39:2799–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Mudo G, Belluardo N, Fuxe K. Nicotinic receptor agonists as neuroprotective/neurotrophic drugs: progress in molecular mechanisms. J Neural Transm 2007;114:135–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Toulorge D, Guerreiro S, Hild A, Maskos U, Hirsch EC, Michel PP. Neuroprotection of midbrain dopamine neurons by nicotine is gated by cytoplasmic Ca2+. FASEB J 2011;25:2563–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Lester HA, Miwa JM, Srinivasan R. Psychiatric drugs bind to classical targets within early exocytotic pathways: therapeutic effects. Biol Psychiatry 2012;72:907–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007;8:519–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science 2011;334:1081–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Gardner BM, Pincus D, Gotthardt K, Gallagher CM, Walter P. Endoplasmic reticulum stress sensing in the unfolded protein response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2013;5:a013169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Lindholm D, Wootz H, Korhonen L. ER stress and neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Death Differ 2006;13:385–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Hoozemans JJ, van Haastert ES, Eikelenboom P, de Vos RA, Rozemuller JM, Scheper W. Activation of the unfolded protein response in Parkinson’s disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007;354:707–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Jiang P, Gan M, Ebrahim AS, Lin WL, Melrose HL, Yen SH. Er stress response plays an important role in aggregation of α-synuclein. Mol Neurodegener 2010;5:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Doyle KM, Kennedy D, Gorman AM, Gupta S, Healy SJ, Samali A. Unfolded proteins and endoplasmic reticulum stress in neurodegenerative disorders. J Cell Mol Med 2011;15:2025–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Stefani IC, Wright D, Polizzi KM, Kontoravdi C. The role of ER stress-induced apoptosis in neurodegeneration. Curr Alzheimer Res 2012;9: 373–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Singleton AB, Farrer M, Johnson J, Singleton A, Hague S, Kachergus J, et al. α-synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson’s disease. Science 2003;302:841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Orenstein SJ, Kuo SH, Tasset I, Arias E, Koga H, Fernandez-Carasa I, et al. Interplay of LRRK2 with chaperone-mediated autophagy. Nat Neurosci 2013;16:394–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, Ide SE, Dehejia A, Dutra A,et al. Mutation in the α-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson’s disease. Science 1997;276:2045–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Kruger R, Kuhn W, Muller T, Woitalla D, Graeber M, Kosel S, et al. Ala30pro mutation in the gene encoding α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease [letter]. Nat Genet 1998;18:106–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Zarranz JJ, Alegre J, Gomez-Esteban JC, Lezcano E, Ros R, Ampuero I, et al. The new mutation, e46k, of α-synuclein causes Parkinson and Lewy body dementia. Ann Neurol 2004;55:164–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Boassa D, Berlanga ML, Yang MA, Terada M, Hu J, Bushong EA, et al. Mapping the subcellular distribution of α-synuclein in neurons using genetically encoded probes for correlated light and electron microscopy: implications for Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. J Neurosci 2013;33: 2605–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Eisbach SE, Outeiro TF. α-synuclein and intracellular trafficking: impact on the spreading of Parkinson’s disease pathology. J Mol Med 2013;91:693–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Dawson TM, Dawson VL. The role of Parkin in familial and sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2010;25(Suppl. 1):S32–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Geisler S, Holmstrom KM, Skujat D, Fiesel FC, Rothfuss OC, Kahle PJ, et al. Pink1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on vdac1 and p62/sqstm1. Nat Cell Biol 2010;12:119–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Geisler S, Holmstrom KM, Treis A, Skujat D, Weber SS, Fiesel FC, et al. The pink1/parkin-mediated mitophagy is compromised by PD-associated mutations. Autophagy 2010;6:871–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Haynes CM, Ron D. The mitochondrial UPR – protecting organelle protein homeostasis. J Cell Sci 2010;123:3849–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]