Abstract

Purpose

Nivolumab, a programmed death-1 inhibitor, prolonged overall survival compared with docetaxel in two independent phase III studies in previously treated patients with advanced squamous (CheckMate 017; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01642004) or nonsquamous (CheckMate 057; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01673867) non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). We report updated results, including a pooled analysis of the two studies.

Methods

Patients with stage IIIB/IV squamous (N = 272) or nonsquamous (N = 582) NSCLC and disease progression during or after prior platinum-based chemotherapy were randomly assigned 1:1 to nivolumab (3 mg/kg every 2 weeks) or docetaxel (75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks). Minimum follow-up for survival was 24.2 months.

Results

Two-year overall survival rates with nivolumab versus docetaxel were 23% (95% CI, 16% to 30%) versus 8% (95% CI, 4% to 13%) in squamous NSCLC and 29% (95% CI, 24% to 34%) versus 16% (95% CI, 12% to 20%) in nonsquamous NSCLC; relative reductions in the risk of death with nivolumab versus docetaxel remained similar to those reported in the primary analyses. Durable responses were observed with nivolumab; 10 (37%) of 27 confirmed responders with squamous NSCLC and 19 (34%) of 56 with nonsquamous NSCLC had ongoing responses after 2 years’ minimum follow-up. No patient in either docetaxel group had an ongoing response. In the pooled analysis, the relative reduction in the risk of death with nivolumab versus docetaxel was 28% (hazard ratio, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.62 to 0.84), and rates of treatment-related adverse events were lower with nivolumab than with docetaxel (any grade, 68% v 88%; grade 3 to 4, 10% v 55%).

Conclusion

Nivolumab provides long-term clinical benefit and a favorable tolerability profile compared with docetaxel in previously treated patients with advanced NSCLC.

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally.1 Non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 85% to 90% of lung cancers.2 Historically, effective treatment options were lacking for patients with NSCLC without actionable driver mutations who experienced disease progression after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. Recognition of the key role of immune system evasion by tumors in cancer pathogenesis, however, has spurred development of immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of various malignancies, including NSCLC.3,4

Nivolumab is an anti–programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitor antibody with robust efficacy and a manageable safety profile across multiple tumor types.5-11 In two randomized, open-label, phase III studies in patients with advanced squamous (CheckMate 017; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01642004)5 or nonsquamous (CheckMate 057; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01673867)6 NSCLC and disease progression during or after platinum-based chemotherapy, nivolumab significantly prolonged overall survival (OS) and had a favorable safety profile compared with docetaxel. On the basis of the results from CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057, nivolumab was approved in the United States,12 the European Union,13 and other countries for use in previously treated advanced NSCLC.

Long-term efficacy and safety data for immune checkpoint inhibitors are limited in patients with NSCLC, especially in randomized studies, compared with chemotherapy. Five-year follow-up from a phase I single-arm nivolumab study in 129 heavily pretreated patients with advanced NSCLC showed durable survival, with a 5-year OS rate of 16%.14 We report updated efficacy and safety data for nivolumab in patients with advanced NSCLC from the CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057 trials with a minimum follow-up of 2 years in all patients.

METHODS

Patients

Eligibility criteria for CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057 have been previously described.5,6 Briefly, patients had stage IIIB/IV NSCLC with squamous (CheckMate 017) or nonsquamous (CheckMate 057) histology. In both studies, patients were required to be ≥18 years of age; to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1, measurable disease per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1)15; disease recurrence or progression during or after one prior platinum-based chemotherapy regimen; and to submit a recent or archival tumor sample for biomarker analyses. In CheckMate 057, an additional line of prior targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy was permitted in patients with known EGFR mutations or ALK translocations. Key exclusion criteria for both studies were autoimmune disease, active interstitial lung disease, systemic immunosuppression (eg, 10 mg daily prednisone) within 14 days, and prior treatment with T-cell costimulation or immune checkpoint–targeted agents or docetaxel.

Study Design

CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057 were international, randomized, open-label, phase III studies.5,6 In each trial, patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive nivolumab (3 mg/kg every 2 weeks) or docetaxel (75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks). Random assignment was stratified by prior paclitaxel use (yes v no) and geographic region (United States or Canada v Europe v rest of the world [Argentina, Australia, Chile, Mexico, and Peru]) in CheckMate 017 and by prior maintenance treatment (yes v no) and line of therapy (second v third) in CheckMate 057.

Patients continued study treatment until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or other protocol-specified reasons. Patients in the nivolumab groups were permitted to continue study treatment after initial disease progression if the investigator determined a clinical benefit and the study drug was tolerated. In the crossover/extension phases of these studies, opened after completion of the primary analyses, patients in the docetaxel groups who were no longer deriving benefit per the treating investigator were eligible to receive nivolumab after a 3-week washout period of prior systemic anticancer therapy.

The studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. The study protocols were approved by an institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each site. All patients provided written informed consent.

Assessments

Tumors were assessed by investigators per RECIST v1.1 at baseline, at 9 weeks, and every 6 weeks thereafter. Patients were followed continuously for survival while receiving study treatment and every 3 months after treatment discontinuation.

Safety was based on reports of adverse events (AEs) and laboratory assessments and monitored throughout the treatment period and at two follow-up visits within 100 days since the last dose of study treatment or before the start of crossover treatment. The severity of AEs was graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0). Select AEs (ie, those with a potential immunologic cause that may require management through immune-modulating medications such as corticosteroids) were grouped according to prespecified categories (endocrine, GI, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, skin, and hypersensitivity/infusion reaction).

Expression of PD-1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) protein was assessed in archival or recent pretreatment tumor biopsy specimens at a central laboratory by using a validated automated immunohistochemical assay (PD-L1 IHC 28-8 pharmDx; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) as previously described.5,6 PD-L1 expression was classified according to prespecified levels (≥ 1%, ≥ 5%, and ≥ 10%) and a post hoc level of ≥ 50%.

Statistical Analysis

Efficacy was assessed in all randomly assigned patients, and safety was assessed in all patients who received one or more doses of study drug. The primary end point of each study, OS, and secondary end points, including objective response rate, progression-free survival (PFS), and efficacy according to PD-L1 protein expression, have been reported.5,6 This update (February 18, 2016, database locks) represents a 24-month follow-up analysis corresponding to an additional 13.6 and 11.0 months of minimum follow-up (defined as the time since random assignment of the last patient to the database lock) in CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057, respectively, since the primary analyses.

Time-to-event end points were compared between treatment groups by using a two-sided log-rank test adjusted for stratification factors for each study; hazard ratios (HRs) and CIs were estimated by using a stratified Cox proportional hazards regression model. Survival curves and rates were estimated by using the Kaplan-Meier method. Post hoc analyses of the treatment effect of PD-L1 expression on OS in the pooled squamous/nonsquamous NSCLC population and of best overall response on OS in each trial were performed, including unstratified HRs and 95% CIs. Safety was analyzed in the pooled squamous/nonsquamous NSCLC population.

RESULTS

Patients and Treatment

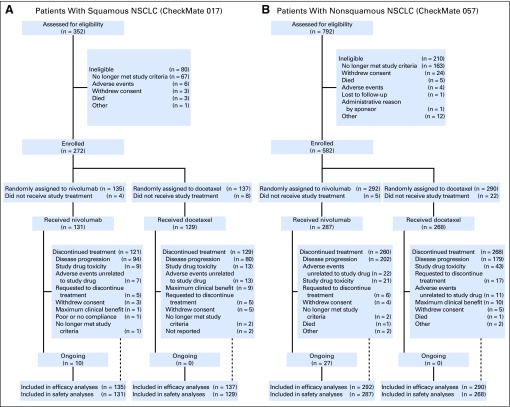

As previously reported,5,6 baseline characteristics were generally well balanced between patients randomly assigned to receive nivolumab (CheckMate 017, n = 135; CheckMate 057, n = 292) and those randomly assigned to receive docetaxel (CheckMate 017, n = 137; CheckMate 057, n = 290; Data Supplement). Patient disposition in each study (as of the February 18, 2016, database locks; minimum follow-up, 24.2 months among patients alive and in the study) is shown in Figure 1. At 2 years, 15 (11%) of 131 patients with squamous NSCLC treated with nivolumab and 34 (12%) of 287 patients with nonsquamous NSCLC treated with nivolumab remained on treatment; no docetaxel-treated patients remained on treatment.

Fig 1.

CONSORT diagram of disposition of patients with (A) squamous non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) or (B) nonsquamous NSCLC.

In the nivolumab and docetaxel groups, respectively, 55 patients (41%) and 44 patients (32%) with squamous NSCLC and 133 patients (46%) and 150 patients (52%) with nonsquamous NSCLC received other systemic therapy subsequent to study treatment, most commonly chemotherapy (Data Supplement). In the docetaxel groups, 11 patients (8%) with squamous NSCLC and 28 (10%) with nonsquamous NSCLC received anti–PD-(L)1 or anti–cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 immunotherapy either during crossover or as subsequent therapy poststudy.

Efficacy

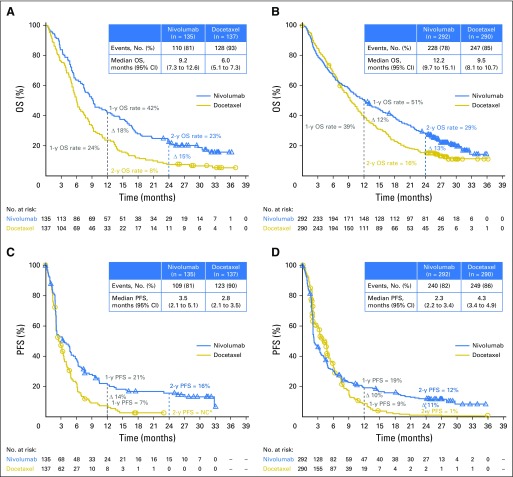

As reported in the primary analyses,5,6 OS remained longer with nivolumab than with docetaxel regardless of histology, with median OS in each study largely unchanged with longer follow-up (Figs 2A and 2B). Differences in OS rates between the nivolumab and docetaxel groups were consistent at 1 and 2 years. Kaplan-Meier–estimated 2-year OS rates were 23% (95% CI, 16% to 30%) with nivolumab versus 8% (95% CI, 4% to 13%) with docetaxel in patients with squamous NSCLC and 29% (95% CI, 24% to 34%) with nivolumab versus 16% (95% CI, 12% to 20%) with docetaxel in patients with nonsquamous NSCLC. Differences in PFS rates, which favored nivolumab over docetaxel, were also consistent at 1 and 2 years (Figs 2C and 2D). Kaplan-Meier–estimated 2-year PFS rates with nivolumab were 16% (95% CI, 10% to 23%) in patients with squamous NSCLC and 12% (95% CI, 8% to 16%) in patients with nonsquamous NSCLC. Given the level of censoring in this analysis after the 2-year time point, OS and PFS estimates after 2 years should be interpreted with caution. In CheckMate 057, patients who did not have an EGFR mutation derived increased OS and PFS benefits with nivolumab versus docetaxel (Data Supplement), whereas patients with EGFR-positive disease had comparable outcomes with nivolumab and docetaxel. Results are consistent with those previously reported in the primary analysis; small numbers of patients with EGFR-positive disease may affect interpretation of these results.6

Fig 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves of (A and B) overall survival (OS) and (C and D) progression-free survival (PFS; investigator assessed) in patients with (A and C) squamous non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) or (B and D) nonsquamous NSCLC. (*) Not calculable (NC) because no patients continued with follow-up for progression at this time point; the PFS rate at the time of the last event was 3%, and the last observation at 2 years was not an event.

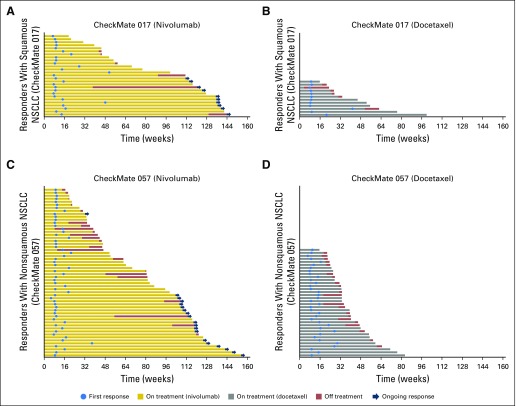

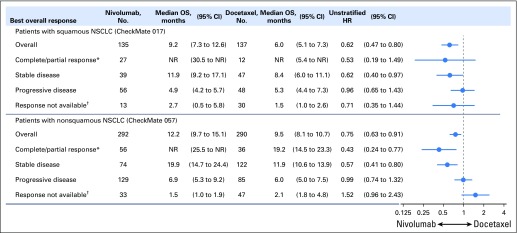

The objective response rates did not change from those reported in the primary analyses5,6 and were higher with nivolumab than with docetaxel (Data Supplement). Of confirmed responders in the nivolumab groups, 10 (37%) of 27 patients with squamous NSCLC and 19 (34%) of 56 patients with nonsquamous NSCLC had ongoing responses after 2 years’ minimum follow-up; no patients in the docetaxel groups had ongoing responses (Fig 3). Eight (80%) of 10 patients with squamous NSCLC and 16 (84%) of 19 patients with nonsquamous NSCLC who had ongoing responses remained on nivolumab treatment; the remaining five responders discontinued treatment as a result of AEs and as of the data cutoff, had maintained ongoing responses without treatment, which ranged from 3.8 to 20.7 months since last dose. Median duration of response was longer with nivolumab than with docetaxel (squamous NSCLC, 25.2 months [95% CI, 9.8 to 30.4 months] v 8.4 months [95% CI, 3.6 months to not estimable]; nonsquamous NSCLC, 17.2 months [95% CI, 8.4 months to not estimable] v 5.6 months [95% CI, 4.4 to 6.9 months]). Patients with disease control (ie, objective response or stable disease as best overall response) demonstrated improved survival with nivolumab versus docetaxel (Fig 4).

Fig 3.

Swimmer plots that show time to first response and duration of response (per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [RECIST] version 1.1) for responders with (A) squamous non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with nivolumab, (B) squamous NSCLC treated with docetaxel, (C) nonsquamous NSCLC treated with nivolumab, and (D) nonsquamous NSCLC treated with docetaxel.

Fig 4.

Treatment effect on overall survival (OS) by best overall response. (*) Confirmed complete and partial response per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 as assessed by the investigator. (†) Includes death before disease assessment, never treated, early discontinuation because of toxicity, and other. HR, hazard ratio; NR, not reached; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer.

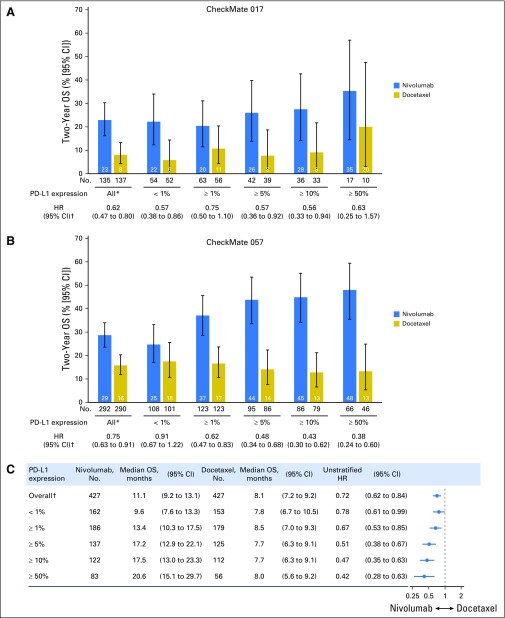

Efficacy by PD-L1 expression in CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057 studies.

Consistent with the primary analyses (Data Supplement),5,6 a 2-year OS benefit with nivolumab versus docetaxel was observed in patients with squamous NSCLC regardless of PD-L1 expression level (Fig 5A). In patients with nonsquamous NSCLC, higher levels of PD-L1 were associated with a greater magnitude of OS benefit with nivolumab (Fig 5B), but treatment benefit also was seen in patients with < 1% PD-L1 expression. In patients with ≥ 50% PD-L1 expression, the HR for OS on the basis of 2 years’ minimum follow-up was 0.63 (95% CI, 0.25 to 1.57) for patients with squamous NSCLC (nivolumab, n = 17; docetaxel, n = 10) and 0.38 (95% CI, 0.24 to 0.60) for patients with nonsquamous NSCLC (nivolumab, n = 66; docetaxel, n = 46). Durable responses were observed with nivolumab across histologies and PD-L1 expression levels (Data Supplement). Of five complete responders (one with squamous NSCLC, four with nonsquamous NSCLC), three had ≥ 1% PD-L1 expression, one had < 1% PD-L1 expression, and one had nonquantifiable PD-L1 expression.

Fig 5.

Efficacy according to programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) expression. Two-year overall survival (OS) rates by PD-L1 expression level in patients with (A) squamous non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and (B) nonsquamous NSCLC and (C) treatment effect on OS by PD-L1 expression (pooled analysis of patients with squamous and nonsquamous NSCLC). (*) All patients include those with no quantifiable PD-L1 expression (CheckMate 017, nivolumab [n = 18; docetaxel, n = 29]; CheckMate 057, nivolumab [n = 61; docetaxel, n = 66]). (†) Hazard ratios (HRs) shown are for overall OS on the basis of 2 years' minimum follow-up.

Pooled analysis of CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057 studies.

In the pooled analysis of OS in the intention-to-treat population (N = 854) with squamous (n = 272 [31.9%]) and nonsquamous (n = 582 [68.1%]) NSCLC, median OS was 11.1 months (95% CI, 9.2 to 13.1 months) with nivolumab versus 8.1 months (95% CI, 7.2 to 9.2 months) with docetaxel (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.62 to 0.84; Fig 5C). Higher PD-L1 expression levels were associated with greater OS benefit with nivolumab (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.28 to 0.63) in patients with ≥ 50% PD-L1 expression, but a benefit was still observed in patients with < 1% PD-L1 expression (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.61 to 0.99).

Safety

After 2 years’ minimum follow-up, the mean treatment duration in CheckMate 017 was 7.5 months (standard deviation [SD], 9.4 months) with nivolumab and 2.5 months (SD, 3.0 months) with docetaxel; median treatment duration was 3.2 months (range, 0 to 33.8 months) and 1.4 months (range, 0 to 20.0 months), respectively. In CheckMate 057, the mean treatment duration was 7.0 months (SD, 9.3 months) with nivolumab and 3.3 months (SD, 3.0 months) with docetaxel; median treatment duration was 2.6 months (range, 0 to 35.7+ months) and 2.3 months (range, 0 to 15.9 months), respectively. Rates of the most frequently reported treatment-related AEs in each study remained similar to those reported in the primary analyses (1 year of minimum follow-up; Data Supplement).5,6

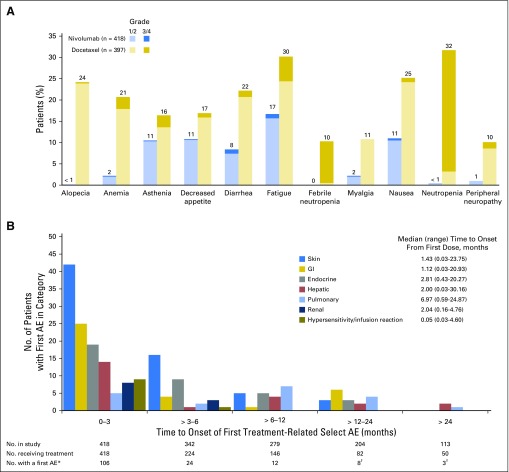

In the pooled safety analysis, treatment-related AEs were reported in fewer patients treated with nivolumab than in patients treated with docetaxel after 2 years’ minimum follow-up (any grade, 68% v 88%; grade 3 to 4, 10% v 55%, respectively) and less frequently led to treatment discontinuation (any grade, 6% v 13%; grade 3 to 4, 4% v 7%, respectively). The most common treatment-related AEs (any grade and grade 3 to 4) were reported in lower proportions of patients treated with nivolumab than in patients treated with docetaxel (Fig 6A). No new treatment-related deaths were reported since the primary analyses.5,6

Fig 6.

(A) Treatment-related adverse events (AEs) reported in ≥ 10% of patients and (B) time to onset of first treatment-related select AE in patients treated with nivolumab (pooled patients with squamous and nonsquamous non–small-cell lung cancer [NSCLC]). (*) Patients with one or more select AEs from first dose until 30 days post-treatment in a given category were counted only once in the time interval corresponding to the first event; patients with multiple events from different categories within the same time interval were counted once in each category. (†) Of the 11 patients with a first AE > 12 months after initiating treatment, one was skin related (grade 2), three were GI related (grade 1 [n = 1] and grade 2 [n = 2]), one was endocrine related (grade 1), three were hepatic related (grade 1 [n = 2] and grade 2 [n = 1]), and three were pulmonary related (grade 1 [n = 1] and grade 2 [n = 2]).

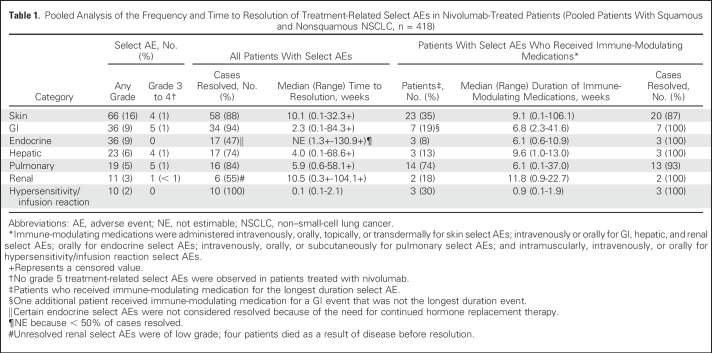

Treatment-related select AEs of any grade were observed in 153 patients (37%) treated with nivolumab; 19 (5%) had grade 3 to 4 treatment-related select AEs. The most common treatment-related select AEs were of the skin (Table 1). The majority of treatment-related select AEs occurred within the first 3 months of nivolumab treatment (Fig 6B). Eleven nivolumab-treated patients had first onset of treatment-related select AEs (in skin, GI, endocrine, hepatic, and pulmonary categories) > 1 year after initiating treatment; all were grade 1 or 2. Median times to onset of treatment-related select AEs by category were < 3 months after initiating nivolumab treatment (Fig 6B), except for pulmonary events (6.97 months).

Table 1.

Pooled Analysis of the Frequency and Time to Resolution of Treatment-Related Select AEs in Nivolumab-Treated Patients (Pooled Patients With Squamous and Nonsquamous NSCLC, n = 418)

Treatment-related select AEs in most of the prespecified categories resolved regardless of immune-modulating medication use (Table 1). Of 36 treatment-related endocrine select AEs, 19 (53%) were considered unresolved because of the need to continue hormone replacement therapy. In patients in whom immune-modulating medications were administered to manage treatment-related select AEs, nearly all AEs resolved. Few patients discontinued nivolumab because of treatment-related select AEs (any grade, 17 [4%]; grade 3 to 4, 9 [2%]; Data Supplement).

DISCUSSION

Given significant improvements in OS and improved tolerability compared with docetaxel, PD-(L)1 agents have become the standard of care for patients with NSCLC with progression while receiving or after platinum-based chemotherapy.16 On the basis of clinically relevant and statistically significant improvements in OS from CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057,5,6 nivolumab was approved by multiple regulatory authorities12,13 and incorporated into clinical practice guidelines for NSCLC treatment.16,17 Additional follow-up from these clinical trials is important to determine whether the survival benefit with nivolumab is sustained and whether new or unexpected safety signals arise with prolonged treatment.

This update shows that after 2 years’ minimum follow-up, nivolumab continues to demonstrate survival benefit compared with docetaxel in previously treated patients with advanced squamous or nonsquamous NSCLC; long-term efficacy is supported by the 2-year OS and PFS rates, which favor nivolumab over docetaxel. The 2-year OS rates are consistent with those previously reported with nivolumab in a phase I study of pretreated patients with advanced NSCLC.14

Of note, durable responses were seen with nivolumab. Of 83 patients across the two studies who achieved an objective response, approximately one third had ongoing responses at the 2-year database lock. In contrast, no patients treated with docetaxel had an ongoing response. The post hoc analysis of the treatment effect of best overall response on OS showed that nivolumab prolonged OS not only in responders but also in patients with stable disease, indicating that a response is not a prerequisite for OS benefit.

As reported in the CheckMate 057 primary subgroup analysis,6 higher levels of tumor PD-L1 expression continued to be associated with a greater magnitude of OS benefit with nivolumab in patients with nonsquamous NSCLC after longer follow-up (2-year OS rate of 48% [95% CI, 36% to 59%] in patients with ≥ 50% PD-L1 expression). Higher 2-year OS rates were observed with nivolumab versus docetaxel in patients with nonsquamous NSCLC across PD-L1 thresholds, including those with no (< 1%) PD-L1 expression. Deep, durable responses with nivolumab were noted across PD-L1 expression levels.

In the pooled safety analysis from CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057, no new safety signals were identified for nivolumab after 2 years’ minimum follow-up. Nivolumab maintained a favorable safety profile compared with docetaxel, with lower rates of commonly reported treatment-related AEs. Most treatment-related select AEs occurred within the first year of nivolumab treatment, although some patients experienced new events after > 1 year. Treatment-related select AEs were well managed with protocol-defined toxicity management algorithms and resolved in the majority of patients.18

The PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab and the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab also are approved for treating patients with advanced NSCLC after prior platinum-based chemotherapy, although pembrolizumab is only approved for use in patients with ≥ 1% PD-L1 expression.19,20 Approvals of pembrolizumab and atezolizumab were based on results of the randomized phase III trials KEYNOTE-010 (Pembrolizumab Versus Docetaxel for Previously Treated, PD-L1-Positive, Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer)21 and OAK (Atezolizumab Versus Docetaxel in Patients With Previously Treated Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer),22 respectively. Key differences were found among CheckMate 017, CheckMate 057, KEYNOTE-010, and OAK. Instead of two independent histology-based studies, the primary efficacy analysis populations in KEYNOTE-010 and OAK were mixed, including patients with squamous and nonsquamous NSCLC. Moreover, different assays to determine PD-L1 expression as well as different PD-L1 thresholds for enrollment and efficacy assessments were used. Consistent with KEYNOTE-01021 and OAK,22 the pooled OS analysis of CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057 (which better mirrors the patient populations of KEYNOTE-010 and OAK) showed that higher PD-L1 expression levels were associated with greater OS benefit with anti–PD-(L)1 therapy; this finding was anticipated given the high proportions of patients with nonsquamous histology in these studies (68% in pooled CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057, 70% in KEYNOTE-010, and 74% in OAK). However, a treatment benefit with nivolumab compared with docetaxel also was observed in patients with < 1% PD-L1 expression in this analysis (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.61 to 0.99).

These updated analyses from CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057 demonstrate long-term clinical benefit with nivolumab in previously treated patients with advanced squamous and nonsquamous NSCLC, including those with high PD-L1 expression as well as those with no or low PD-L1 expression. Nivolumab showed sustained tolerability, with a favorable safety profile compared with docetaxel. These data support nivolumab as a standard-of-care treatment option in this broad patient population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the patients and their families as well as the clinical study teams for making these studies possible (complete lists of CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057 investigators are shown in the Data Supplement). We also thank Jessica Proszynski for contributions as protocol manager for these studies and Dako for collaborative development of the automated PD-L1 immunohistochemistry assay. Professional medical writing assistance was provided by Kerry Brinkman and Joanna Bloom of Evidence Scientific Solutions.

Footnotes

Supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Presented in part at the 52nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Chicago, IL, June 3-7, 2016, and the European Society for Medical Oncology 2016 Congress, Copenhagen, Denmark, October 7-11, 2016.

Clinical trial information: NCT01642004 and NCT01673867.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Leora Horn, David R. Spigel, Everett E. Vokes, Esther Holgado, Neal Ready, Martin Steins, Elena Poddubskaya, Hossein Borghaei, Enriqueta Felip, Luis Paz-Ares, Adam Pluzanski, Karen L. Reckamp, Marco A. Burgio, Martin Kohlhäeufl, David Waterhouse, Fabrice Barlesi, Scott Antonia, Oscar Arrieta, Jérôme Fayette, Lucio Crinò, Naiyer Rizvi, Martin Reck, Matthew D. Hellmann, William J. Geese, Ang Li, Anne Blackwood-Chirchir, Diane Healey, Julie Brahmer, Wilfried E.E. Eberhardt

Provision of study materials or patients: Leora Horn, David R. Spigel, Everett E. Vokes, Esther Holgado, Neal Ready, Martin Steins, Elena Poddubskaya, Hossein Borghaei, Enriqueta Felip, Luis Paz-Ares, Adam Pluzanski, Karen L. Reckamp, Marco A. Burgio, Martin Kohlhäeufl, David Waterhouse, Fabrice Barlesi, Scott Antonia, Oscar Arrieta, Jérôme Fayette, Lucio Crinò, Naiyer Rizvi, Martin Reck, Matthew D. Hellmann, Julie Brahmer, Wilfried E.E. Eberhardt

Collection and assembly of data: Leora Horn, David R. Spigel, Everett E. Vokes, Esther Holgado, Neal Ready, Martin Steins, Elena Poddubskaya, Hossein Borghaei, Enriqueta Felip, Luis Paz-Ares, Adam Pluzanski, Karen L. Reckamp, Marco A. Burgio, Martin Kohlhäeufl, David Waterhouse, Fabrice Barlesi, Scott Antonia, Oscar Arrieta, Jérôme Fayette, Lucio Crinò, Naiyer Rizvi, Martin Reck, Matthew D. Hellmann, William J. Geese, Ang Li, Anne Blackwood-Chirchir, Diane Healey, Julie Brahmer, Wilfried E.E. Eberhardt

Data analysis and interpretation: Leora Horn, David R. Spigel, Everett E. Vokes, Esther Holgado, Neal Ready, Martin Steins, Elena Poddubskaya, Hossein Borghaei, Enriqueta Felip, Luis Paz-Ares, Adam Pluzanski, Karen L. Reckamp, Marco A. Burgio, Martin Kohlhäeufl, David Waterhouse, Fabrice Barlesi, Scott Antonia, Oscar Arrieta, Jérôme Fayette, Lucio Crinò, Naiyer Rizvi, Martin Reck, Matthew D. Hellmann, William J. Geese, Ang Li, Anne Blackwood-Chirchir, Diane Healey, Julie Brahmer, Wilfried E.E. Eberhardt

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Nivolumab Versus Docetaxel in Previously Treated Patients With Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Two-Year Outcomes From Two Randomized, Open-Label, Phase III Trials (CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057)

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Leora Horn

Honoraria: Biodesix

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Bayer AG, Xcovery, Genentech, Eli Lilly, AbbVie, AstraZeneca

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb

David R. Spigel

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech (Inst), Roche (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Biodesix (Inst), Boehringer Ingelheim (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Celgene (Inst), Clovis Oncology (Inst), Eli Lilly (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Pfizer (Inst)

Research Funding: Genentech (Inst), Roche (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Astex Pharmaceuticals (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), BIND Biosciences (Inst), Boehringer Ingelheim (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Celgene (Inst), Clovis Oncology (Inst), CytRx (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo (Inst), EMD Serono (Inst), ImClone Systems (Inst), ImmunoGen (Inst), Eli Lilly (Inst), Novartis (Inst), OncoGenex Pharmaceuticals (Inst), OncoMed (Inst), Peregrine Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Verastem (Inst)

Everett E. Vokes

Stock or Other Ownership: McKesson

Consulting or Advisory Role: AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Leidos Biomedical Research, Merck, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Merck Serono, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, VentiRx Pharmaceuticals

Esther Holgado

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Roche, Novartis

Speakers’ Bureau: Celgene, Roche

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Celgene, Roche

Neal Ready

Honoraria: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Heat Biologics, Merck, ARIAD Pharmaceuticals

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca

Martin Steins

Honoraria: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Elena Poddubskaya

No relationship to disclose

Hossein Borghaei

Honoraria: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Celgene, Genentech, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, EMD Serono, Trovagene, Merck, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Genmab

Research Funding: Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Merck (Inst), Celgene (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Celgene, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Merck

Other Relationship: University of Pennsylvania Data Safety Monitoring Board

Enriqueta Felip

Honoraria: Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche

Consulting or Advisory Role: Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche

Speakers’ Bureau: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Roche, Pfizer

Luis Paz-Ares

Honoraria: Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, MSD, Pfizer, Roche, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Novartis, AbbVie

Adam Pluzanski

Consulting or Advisory Role: Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Roche, Genentech

Speakers’ Bureau: Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, MSD, Roche, Genentech, Pierre Fabre

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Genentech

Karen L. Reckamp

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Astellas Pharma, Nektar, Euclises Pharmaceuticals

Research Funding: GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Novartis (Inst), ARIAD Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Eisai (Inst), Clovis Oncology (Inst), Xcovery (Inst), Gilead Sciences (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Adaptimmune (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Roche (Inst)

Marco A. Burgio

No relationship to disclose

Martin Kohlhäeufl

Honoraria: Bristol-Myers-Squibb

Research Funding: Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Roche

David Waterhouse

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, AbbVie

Speakers’ Bureau: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Roche, Genentech

Fabrice Barlesi

Honoraria: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Scott Antonia

Stock or Other Ownership: Cellular Biomedicine Group

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim

Oscar Arrieta

Speakers’ Bureau: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer

Research Funding: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer

Jérôme Fayette

Leadership: Glycotope

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb

Lucio Crinò

Speakers’ Bureau: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis

Naiyer Rizvi

Leadership: ARMO Biosciences

Stock or Other Ownership: Gritstone Oncology, ARMO Biosciences

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, MedImmune, Genentech, Roche, Novartis, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Eli Lilly

Martin Reck

Consulting or Advisory Role: Proacta, Eli Lilly, MSD Oncology, Merck Serono, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Pfizer, Novartis

Speakers’ Bureau: Roche, Genentech, Eli Lilly, MSD Oncology, Merck Serono, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Pfizer, Novartis

Matthew D. Hellmann

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Genentech, AstraZeneca, MedImmune, Novartis, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Mirati Therapeutics

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb

William J. Geese

Employment: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Stock or Other Ownership: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Ang Li

Employment: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Anne Blackwood-Chirchir

Employment: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Stock or Other Ownership: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Sanofi, Gilead Sciences

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Genentech

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Diane Healey

Employment: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Stock or Other Ownership: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer

Julie Brahmer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Celgene, Syndax, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Merck, AstraZeneca, MedImmune

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Merck (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), Incyte (Inst), Five Prime Therapeutics (Inst), Janssen Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck

Other Relationship: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck

Wilfried E.E. Eberhardt

Honoraria: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, AstraZeneca, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Guardant Health, Hexal, Amgen, Celgene, Daichi Sankyo, Abbott, AbbVie

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, AstraZeneca, Roche, Novartis, Pfizer, Bayer AG, Eli Lilly, Abbott, AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene

Research Funding: Eli Lilly (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Boehringer Ingelheim

REFERENCES

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. : Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 65:87-108, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/non-small-cell-lung-cancer.html American Cancer Society: Non-small cell lung cancer.

- 3.Pardoll DM: The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 12:252-264, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melosky B, Chu Q, Juergens R, et al. : Pointed progress in second-line advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: The rapidly evolving field of checkpoint inhibition. J Clin Oncol 34:1676-1688, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. : Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 373:123-135, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. : Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 373:1627-1639, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. : Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med 372:320-330, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. : Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 373:1803-1813, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferris RL, Blumenschein G, Jr, Fayette J, et al. : Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 375:1856-1867, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, et al. : PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 372:311-319, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Younes A, Santoro A, Shipp M, et al. : Nivolumab for classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma after failure of both autologous stem-cell transplantation and brentuximab vedotin: A multicentre, multicohort, single-arm phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 17:1283-1294, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Opdivo [package insert]. Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ. 2017.

- 13. Opdivo [summary of product characteristics]. Bristol-Myers Squibb, Uxbridge, United Kingdom. 2017.

- 14. Brahmer J, Horn L, Jackman DM, et al: Five-year follow-up from the CA209-003 study of nivolumab in previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Clinical characteristics of long-term survivors. American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, 2017 [abstr CT077] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. : New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45:228-247, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, NCCN Evidence Blocks: non-small cell lung cancer version 4.2017, 2017.

- 17.Novello S, Barlesi F, Califano R, et al. : Metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 27:v1-v27, 2016. (suppl 5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber JS, Postow M, Lao CD, et al. : Management of adverse events following treatment with anti-programmed death-1 agents. Oncologist 21:1230-1240, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Keytruda [package insert]. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp, Whitehouse Station, NJ. 2016.

- 20. Tecentriq [package insert]. Genentech, San Francisco, CA. 2016.

- 21.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, et al. : Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 387:1540-1550, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, et al. : Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): A phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 389:255-265, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]