Abstract

An estimated 20% of patients with cancer will develop brain metastases. Approximately 200,000 individuals in the United States alone receive whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT) each year to treat brain metastases. Historically, the prognosis of patients with brain metastases has been poor; however, with new therapies, this is changing. Because patients are living longer following the diagnosis and treatment of brain metastases, there has been rising concern about treatment-related toxicities associated with WBRT, including neurocognitive toxicity. In addition, recent clinical trials have raised questions about the use of WBRT. To better understand this rapidly changing landscape, this review outlines the treatment roles and toxicities of WBRT and alternative therapies for the management of brain metastases.

INTRODUCTION

Since the 1950s, whole-brain radiation therapy (WBRT) has been the most widely used treatment for patients with multiple brain metastases, given its effectiveness in palliation, widespread availability, and ease of delivery.1 Historically, there was limited focus on the toxicities of WBRT, such as cognitive deterioration, because the vast majority of patients with brain metastases had a poor prognosis. More recently, with improvements in both focal and systemic therapies, prognosis has improved for patients with brain metastases, and clinical trials have better defined the toxicity profile of WBRT.2,3 In addition, a recent trial in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with poor prognosis found no benefit from WBRT compared with best supportive care, which was a significant finding because palliation has been the cornerstone of WBRT.4 These advancements and the knowledge gained from these clinical trials have raised questions about the use of WBRT. To better understand this rapidly changing landscape, this review outlines the treatment roles and toxicities of WBRT and alternative therapies for the management of brain metastases.

TREATMENT ROLES OF WBRT

Adjuvant WBRT After Radiosurgery

Several retrospective studies have explored the role of adjuvant WBRT after radiosurgery, suggesting an increase in tumor control at the radiosurgical sites and a prevention of new brain metastases.5,6 To further investigate these findings, the Japanese Radiation Oncology Study Group (JROSG) 99-1 trial randomly assigned 132 patients with one to four metastases to radiosurgery alone or to radiosurgery plus WBRT.7 At 12 months, adjuvant WBRT resulted in an increased control rate at the radiosurgical sites of 89% versus 73% for radiosurgery alone (P = .002) and a decreased risk for new brain metastases of 42% versus 64% for radiosurgery alone (P = .003). No significant reduction in neurologic deaths was observed, and there was no difference in overall survival between the study arms. The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 22952-26001 trial was performed to specifically address whether adjuvant WBRT increases duration of functional independence.8 Adjuvant WBRT reduced the 2-year relapse rate at initial sites (19% v 31%; P = .040) and at new sites (33% v 48%; P = .023); however, there were no differences in functional independence or overall survival between the study arms. Adjuvant WBRT was associated with worse quality of life (QOL), predominantly during the early follow-up period.9 A phase III trial conducted at MD Anderson Cancer Center (ID00-377) randomly assigned patients with one to three brain metastases to stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) and WBRT or SRS alone and again found significantly improved intracranial control with the addition of WBRT (1-year freedom from CNS recurrence 73% v 27%; P = .0003).10 However, despite improved intracranial control with WBRT, the trial was closed early because the patients assigned to SRS and WBRT were more likely to have deterioration in learning and memory function (52% v 24%, respectively). An individual patient data meta-analysis of JROSG 99-1, EORTC 22952-26001, and MD Anderson Cancer Center trials found no survival benefit with adjuvant WBRT despite improved intracranial control.11 Potential reasons for the lack of survival benefit from WBRT include the longer interruption of systemic therapy with WBRT compared with SRS and the success of salvage therapy at the time of intracranial progression (necessitating close follow-up with serial imaging with an SRS-alone approach).10 In addition, prospective trials of SRS alone have shown that extracranial disease progression is the most common cause of death, with < 10% of patients dying as the result of intracranial progression alone.12

Alliance trial N0574 assessed the effect of adjuvant WBRT on both QOL and cognitive function.3 This trial randomly assigned 213 patients with one to three brain metastases to SRS alone or SRS and WBRT. The primary end point, cognitive deterioration at 3 months, was more frequent after SRS plus WBRT than after SRS alone (92% v 64%; P < .001). QOL was also worse at 3 months with the addition of WBRT. There was no difference in median overall survival despite improved intracranial control. An analysis of long-term survivors found worse cognitive function at 12 months for those patients treated with adjuvant WBRT. Taking these trials in context, noting the absence of a difference in survival and better cognitive and QOL outcomes, SRS alone is the preferred strategy for the treatment of patients with limited brain metastases.

Adjuvant WBRT After Surgery

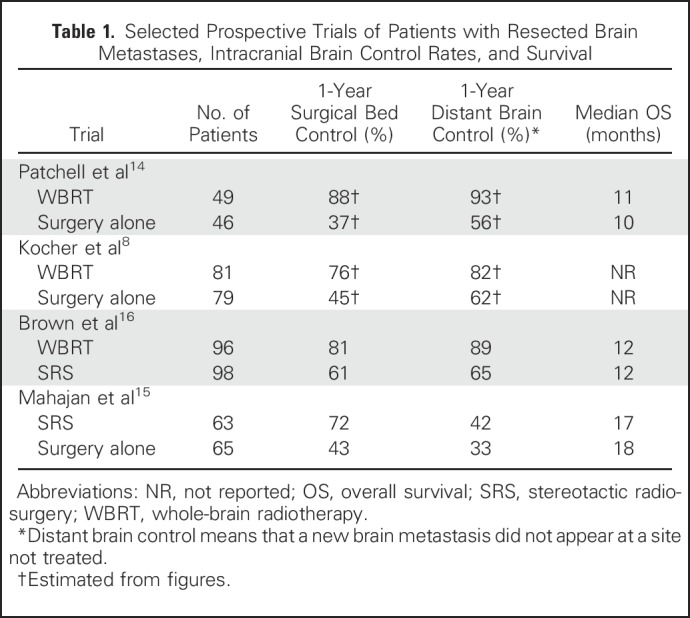

Surgical resection of brain metastases, typically performed on larger lesions with mass effect, has been shown to have a survival benefit.13 However, even after magnetic resonance imaging–confirmed gross total resection, there is approximately a 50% risk of local recurrence in the surgical bed (Table 1).14-16 Postoperative (adjuvant) WBRT reduces the risk of recurrence in the surgical bed and development of new (ie, distant) brain metastases by more than half, as well as death from neurologic causes; however, these benefits have not been shown to translate into an overall survival prolongation, recognizing that these clinical trials were not powered to assess surival.8,14

Table 1.

Selected Prospective Trials of Patients with Resected Brain Metastases, Intracranial Brain Control Rates, and Survival

There is a growing interest in the use of radiosurgery in the postoperative setting, because radiosurgery has the advantage of sparing patients the acute and late toxicities of WBRT. To assess the effect of radiosurgery on surgical bed control, MD Anderson Cancer Center 2009-0381, a single-institution phase III trial randomly assigned 132 patients to radiosurgery to the surgical cavity or observation after complete resection of brain metastases; the study found that surgical bed control rates were significantly improved after radiosurgery compared with resection alone (surgical bed control at 12 months 72% v 43%, respectively; P = .015).15 A multicenter trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier:NCT01535209) randomly assigned 59 patients with a resected brain metastasis to radiosurgery or WBRT with no difference in surgical bed control (74% v 75%; P = 1).17 The primary end point was neurologic (ie, clinician rated)/cognitive (ie, Mini-Mental State Examination) failure or neurologic death, and the trial did not demonstrate noninferiority of radiosurgery compared with WBRT. An Alliance/Canadian Cancer Trials Group cooperative group, multi-institutional phase III trial, N107C/CEC.3, randomly assigned 194 adult patients with a resected brain metastasis to either radiosurgery or WBRT; for the coprimary end points, the study found better preservation of cognitive function on a battery of tests (Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised [HVLT-R], Trail Making Test [TMT], and Controlled Oral Word Association [COWA]) with radiosurgery and no difference in survival between the study arms.16 Cognitive deterioration was significantly more frequent in the WBRT arm (52.1% v 14.8% at 6 months, respectively; P < .001), and QOL was significantly worse despite better intracranial control with WBRT including surgical bed control (80.6% v 60.5%; P < .001). On the basis of the findings of these phase III trials, radiosurgery in the postoperative setting is a standard of care to improve surgical bed control relative to observation and is a less toxic alternative than WBRT. However, future research is needed to refine the radiosurgery technique (eg, fractionated, preoperative radiosurgery) to further improve on outcomes such as surgical bed control.

Multiple Brain Metastases

Although prior studies of radiosurgery alone have primarily been limited to patients with oligo-brain metastases (ie, one to four brain metastases), significant advances and more widespread adoption of radiosurgical technology have permitted radiosurgical management of multiple brain metastases.3,7,8,10 However, because no prospective randomized trial has examined the consequences of its omission, upfront WBRT remains a standard approach for patients with multiple brain metastases. In combination with WBRT, for multiple brain metastases, radiosurgery is commonly reserved for salvage therapy or as consolidative boost therapy for larger lesions or radioresistant histologic types such as melanoma or renal cell carcinoma.18

Palliative

Historically, palliative treatment has been the primary role of WBRT. Prospective trials have shown complete or partial responses in > 60% of brain metastases treated with WBRT and palliation of presenting symptoms in more than half of patients; however, cognitive function was not evaluated in these studies.1,19 The role of WBRT for patients with poor-prognosis brain metastases was recently assessed by the Quality of Life after Treatment for Brain Metastases (QUARTZ) trial, which randomly assigned 538 patients with NSCLC with brain metastases to either WBRT plus supportive care or supportive care alone.4 Patients were only enrolled if they were deemed unsuitable for radiosurgery or surgery and if there was uncertainty about the potential benefit of WBRT.20 A significant proportion of patients enrolled had poor performance status (38% had a Karnofsky performance status < 70), and the vast majority of patients received dexamethasone (median, 8 mg daily) irrespective of presence or absence of neurologic symptoms. There was no difference in median survival (9.2 weeks WBRT v 8.5 weeks; P = .808), QOL, or corticosteroids use between study arms. However, on further analysis, better-prognosis subgroups, such as patients younger than 60 years, had improved survival with WBRT. The QUARTZ trial suggests that WBRT provides no benefit compared with best supportive care for patients with poor-prognosis NSCLC with asymptomatic brain metastases; however, WBRT remains the primary palliative treatment for the majority of patients with brain metastases.

TOXICITY OF WBRT

Typical acute adverse effects of WBRT include temporary alopecia, mild dermatitis, mild fatigue, and less commonly otitis media or externa. Infrequently, worsening of pretreatment cognitive and neurologic deficits may develop during treatment as the consequence of a transient peritumoral edema, which usually responds to a short-term increase or the initiation of corticosteroids.

Several randomized clinical trials have demonstrated cognitive decline after treatment that includes WBRT.3,10,16 These trials have detected cognitive decline with validated, multidimensional, and cognitive tests of episodic memory (HVLT-R), executive function (TMT Part B, COWA), processing speed (TMT Part A), and fine motor control (grooved pegboard). In these studies, 35% to 52% of patients had a 3–standard deviation (SD) drop on cognitive testing 3 to 6 months after WBRT, which was increased relative to 6% to 24% of patients with a 3-SD drop after SRS.3,16 Interestingly, these trials have demonstrated a particularly pronounced toxicity of WBRT on episodic memory that is greater than the other domains of cognition assessed.

Although important, demonstration of these cognitive effects has important limitations. It is possible that patients may initially have a decline in cognitive function and later a recovery, because most studies use a time-to-event analysis instead of reporting cognitive function serially over time. However, most patients with brain metastases in these trials did not live beyond 4 to 6 months, diminishing the relevance of such a long-term follow-up question for the vast majority. A small subset of patients enrolled in N0574 survived ≥ 12 months and completed cognitive testing that confirmed greater cognitive decline in patients treated with upfront SRS plus WBRT compared with SRS alone.3 As defined populations of patients with brain metastases are identified who have longer survivorship and are treated with radiation, it will be important to carefully evaluate cognitive risks and benefits of different radiation treatment approaches in the months and years following treatment. Lastly, although trials have demonstrated cognitive and QOL effects from WBRT, one study found both episodic memory decline and self-reported cognitive complaints but limited correlation between decline in tested cognitive function and patient-reported cognitive function.21 Discordance between objective cognitive test results and subjective complaints is frequently observed in many neurologic populations, including those with well-known cognitive disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, underscoring the importance of objectively measuring cognition with performance-based neuropsychological tests rather than patient-reported outcomes.22

Clinically overt, debilitating dementia associated with WBRT manifests in a small minority of patients (< 5%), and is the more severe end of the spectrum of cognitive decline reported in clinical trials.23 Radiation-induced dementia in its most severe form can be accompanied by other symptoms such as gait instability and urinary incontinence, and more commonly occurs with larger radiation dose per treatment (> 3.5 Gy per treatment) and/or higher total radiation dose.23

Treatments to Prevent or Ameliorate WBRT Toxicity

Unlike most events that cause cognitive decline, WBRT is planned. Therefore, there is great interest in pharmacologic agents to prophylactically mitigate cognitive toxicity from WBRT. Memantine is a noncompetitive, low-affinity, open-channel antagonist of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor that blocks pathologic excessive stimulation of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors. In preclinical models, memantine has been shown to be neuroprotective,24,25 and in two placebo-controlled phase III trials memantine proved to be a well-tolerated, effective treatment for vascular dementia.26,27 The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trial (RTOG) 0614 randomly assigned 554 patients with brain metastases receiving WBRT to either memantine or placebo.28 The memantine was well tolerated, and rates of toxicity were similar between placebo and memantine. There was less decline in episodic memory (HVLT-R delayed recall) in the memantine arm compared with placebo (0.0 compared with −0.9 SDs) at 24 weeks (P = .059). However, the difference was not statistically significant, possibly caused by a lack of statistical power because there were only 149 analyzable patients at 24 weeks as the result of patient death and disease progression. The memantine arm had significantly longer time to cognitive decline (hazard ratio, 0.78; P = .01), and the probability of cognitive function failure at 24 weeks was 54% in the memantine arm and 65% in the placebo arm. Superior results were also observed in the memantine arm for executive function, processing speed, and other measures of episodic memory.

If cognitive symptoms arise after radiotherapy, it is important to evaluate potential contributing factors such as tumor progression, fatigue, or depression. For postradiation cognitive symptoms, many pharmacologic agents have been tested and shown little benefit. Donepezil, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor that is used to treat Alzheimer’s dementia, has shown some promise for postradiation cognitive symptoms. In a phase III trial, 198 patients with brain tumors were randomly assigned to donepezil or placebo 6 months after WBRT or partial brain radiation.29 There was no statistically significant difference in the composite neurocognitive scores between study arms at 6 months; however, on subgroup analysis, patients with greater pretreatment cognitive impairment were found to have benefit with donepezil.

ALTERNATIVE TREATMENTS

Radiosurgery Alone

There is strong evidence supporting radiosurgery alone for patients with limited brain metastases amenable to radiosurgery. For patients with multiple brain metastases, arbitrarily typically defined as five to 10 (or five to 15) lesions, the role of radiosurgery alone is more controversial.30 Japanese Leksell Gamma Knife (JLGK) trial 0901, a multi-institutional prospective observational study, treated 1,194 patients with one to 10 newly diagnosed brain metastases with radiosurgery alone.12 The patients enrolled in this trial had relatively small-volume brain disease (total cumulative volume ≤ 15 mL). Overall survival did not differ between those with two to four metastases and those with five to 10 metastases (P = .78; median overall survival, 10.8 v 10.8 months, respectively). In JLGK0901, although only 9% of patients received salvage WBRT, few suffered a neurologic death and the vast majority died as the result of systemic disease progression, suggesting that a radiosurgery-alone approach may be a reasonable treatment for patients with multiple brain metastases. However, it should be recognized that patients enrolled in JLGK0901 may be different than patient populations in North America or Europe, because mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) are more prevalent among the Japanese population. To our knowledge, there are no published randomized trials evaluating the role of radiosurgery alone with omission of upfront WBRT in patients with four or more brain metastases. However, there are ongoing trials (such as a phase III trial at MD Anderson Cancer Center [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01592968]) that randomly assigns patients with four to 15 brain metastases to WBRT or SRS with primary end points of local tumor control and cognitive function. A similar trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02353000) in the Netherlands is currently enrolling patients with four to 10 brain metastases with QOL as the primary end point. Off study, if radiosurgery alone is used to treat multiple metastases it is important to emphasize that close follow-up (eg, every 2 months for the first year) with serial magnetic resonance imaging is warranted, because approximately half of patients will develop new metastases.

Systemic Therapy

Traditional chemotherapy has had a limited role in the management of patients with brain metastases, and its use was usually limited to patients who had experienced disease relapse after use of either WBRT or SRS. However, recent advances in novel agents (eg, tyrosine kinase inhibitors [TKIs] with better blood-brain barrier [BBB] penetration and immunotherapy that results in high responses in brain metastases) has increased the role of systemic therapies in the management of this patient population.31

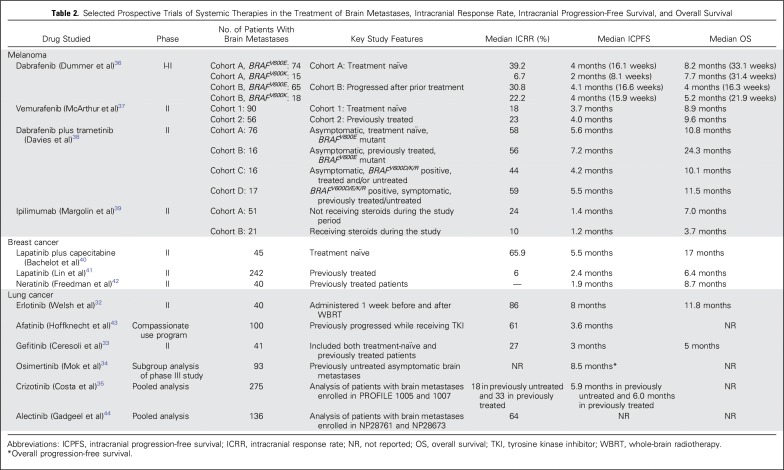

Lung cancer, breast cancer, and melanoma account for the majority of cases of brain metastases, and most of the prospective clinical trials have focused on these malignancies (Table 2).32-44 However, most of these trials are single-arm phase II studies rather than randomized clinical trials. First-generation TKIs such as erlotinib, gefitinib, or crizotinib had more limited BBB penetration; however, next-generation TKIs such as osimertinib, ceritinib, and alectinib have better ability to cross the BBB. The response rates with use of erlotinib, gefitinib, and osimertinib in EGFR mutation–positive lung cancer brain metastases have been reported in prospective trials to range from 50% to 80%, resulting in progression-free survival of 6 to 12 months and overall survival of 15 to 22 months.32-34 The response rates for patients enrolled in prospective trials of crizotinib are approximately 20%, which increase to 50% to 70% with the use of next-generation inhibitors such as alectinib, brigatinib, and ceritinib in ALK-rearranged lung cancer brain metastases.35, 45-47 A phase II trial of the combination of lapatinib and capecitabine resulted in a response rate of 66% in WBRT-naïve human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive breast cancer brain metastases; however, the response rate was 20% in those for whom prior radiation had failed.40 A phase II trial evaluating neratinib and capecitabine was associated with 50% response rates in brain metastases in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive breast cancer.48 A phase II trial of vemurafenib resulted in response rates of approximately 20% to 25% in BRAF mutation–positive melanoma brain metastases.37 Response rates of 30% to 38% were reported with dabrafenib in a phase II trial.49 The combination of dabrafenib and trametinib in a phase II trial resulted in a responses rate of 55% in asymptomatic BRAFV600E brain metastases.38 The higher responses were observed in WBRT or radiation-naïve patients compared with those for whom prior radiation had failed.50 Although high response rates are observed with the use of TKIs, a limitation of these agents is that the durability of response is < 1 year for most agents. Immune checkpoint inhibitors that target cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 and programmed cell death (PD) 1 axis have shown initial promise in patients with lung cancer and melanoma brain metastases.51 In a phase II trial, ipilimumab monotherapy produced disease control rates of 25% in patients who were not receiving steroids and 10% in those who were receiving steroids for melanoma brain metastases.39 A phase II trial of pembrolizumab monotherapy showed a brain metastasis response rate of 22% in patients with melanoma and 33% in patients with NSCLC.52 A combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab assessed in a phase II trial was associated with response rates of 45% to 55% in melanoma brain metastases.53 The advantage of immunotherapy is that, unlike TKIs, the responses are more durable (ie, > 1 year).

Table 2.

Selected Prospective Trials of Systemic Therapies in the Treatment of Brain Metastases, Intracranial Response Rate, Intracranial Progression-Free Survival, and Overall Survival

Although there have been many advances in the management of brain metastases with systemic therapy, there needs to be some caution in withholding cranial radiotherapy (SRS or WBRT). For example, a multi-institution retrospective study of 202 patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC with brain metastases found that treatment with EGFR-TKIs alone and the deferral of radiotherapy was associated with inferior survival compared with those patients who were treated up front with cranial radiotherapy followed by EGFR-TKIs.54 Although some data are available, more studies are needed to assess the timing and sequencing of systemic therapy/immunotherapy and cranial radiation, in addition to investigating the efficacy and toxicity of combining the two treatment modalities.55 Finally, most of the targeted therapy or immunotherapy trials have included patients with asymptomatic brain metastases and have not assessed cognitive function, which is critical in trials of neurologic disease and therapies directed at the brain. Hence, the next generation of trials will need to evaluate the combination of these systemic agents with either SRS or WBRT to examine not only the efficacy but also the toxicity associated with such approaches.

Alternating Electric Field Therapy

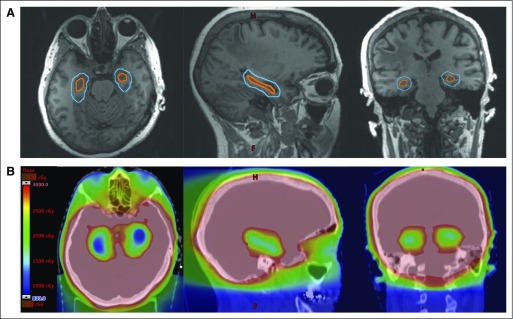

Extensively tested in the setting of newly diagnosed and recurrent glioblastoma, tumor-treating fields (TTFields) represent a noninvasive and potentially novel approach to treating intracranial micrometastatic disease, potentially without the cognitive effects of WBRT (Fig 1). Through the placement of transducer arrays on the shaved scalp, TTFields deliver alternating electric fields with low intensity and intermediate frequency to the brain parenchyma. These alternating electric fields have antimitotic activity against tumor cells through the disruption of mitotic spindle formation during metaphase and through the dielectrophoretic dislocation of intracellular constituents, resulting in apoptosis. In the setting of newly diagnosed glioblastoma, studies demonstrating antimitotic activity of TTFields in vitro and in vivo have translated into a phase III trial demonstrating an overall survival benefit with the addition of TTFields to conventional chemoradiotherapy.56 Similarly significant activity of TTFields has been observed in preclinical models of NSCLC.57 Building upon these promising preclinical results, METIS (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02831959) is an ongoing phase III trial of radiosurgery alone versus radiosurgery plus TTFields for patients with one to 10 brain metastases. The primary objective of this currently enrolling study is to determine whether TTFields prolongs the time to first intracranial progression. Importantly, cognitive function is also being evaluated in this trial of a new therapeutic approach.

Fig 1.

Tumor treating fields are administered by four transducer arrays placed on the shaved scalp and connected to a portable device.

Hippocampal-Avoidance WBRT

The generation of new neurons from mitotically active neural stem cells located within the subgranular zone of the hippocampal dentate gyrus has been observed to be central to new memory formation.58 Preclinical studies have demonstrated that injury to these neural stem cells from relatively modest doses of radiation may contribute to radiotherapy-induced cognitive toxicity and have been supported by additional clinical studies observing a dose-response relationship between dose received by the hippocampus and risk of postradiotherapy decline in episodic memory.59 Modern intensity-modulated radiotherapy techniques have been developed to conformally avoid this hippocampal neural stem cell compartment while delivering therapeutic radiation dose to the remaining whole-brain parenchyma (Fig 2). These techniques, often referred to as hippocampal-avoidance WBRT, were tested in a single-arm phase II trial in patients with brain metastases.21 The primary end point of this trial, the mean relative decline in HVLT-R delayed recall score from baseline to 4 months, was 7%, which was significant compared with the 30% mean relative decline in HVLT-R delayed recall with the historical control (P < .001). The trial found that hippocampal-avoidance WBRT was associated with highly promising preservation of memory and QOL compared with historical controls. To validate these phase III findings, NRG Oncology-CC001 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02360215) is an ongoing phase III trial of WBRT with memantine with or without hippocampal avoidance for patients with brain metastases, with the primary outcome of time to neurocognitive failure. In addition, NRG Oncology-CC003 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02635009) is an ongoing randomized phase II/III trial of prophylactic cranial irradiation with or without hippocampal avoidance for small-cell lung cancer, with the primary outcomes of intracranial relapse rate and time to deterioration in episodic memory.

Fig 2.

(A) The hippocampal avoidance region (blue) is generated by expanding the hippocampal contour (orange) by 5 mm. (B) Color wash dose distributions for hippocampal-avoidance whole-brain radiotherapy are shown on representative axial, sagittal, and coronal images.

SUMMARY

The management of patients with brain metastases is rapidly evolving; WBRT is no longer the default treatment for patients with brain metastases. Because of the recent better understanding of the effect of WBRT on cognitive function and QOL, the use of WBRT should be judicious and considered in the context of other treatment options such as radiosurgery. In addition, if clinically appropriate alternative treatment options are available, many clinicians will follow a treatment paradigm of delaying WBRT to later in a patient’s disease course. Treatment options will continue to increase, especially with the exploitation of the molecular characteristics of tumors. With the complexities of treatment decisions for this patient population, a multidisciplinary approach is needed to optimize management of patient care. Finally, with the detrimental effect of brain metastases, further research is needed to improve the therapeutic ratio of interventions21,28 and to prevent the development of brain metastases in patients with cancer.60

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Whole-Brain Radiotherapy for Brain Metastases: Evolution or Revolution?

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Paul D. Brown

Honoraria: UpToDate

Manmeet S. Ahluwalia

Honoraria: Prime Oncology, Elsevier, Itamar Medical (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Monteris Medical, Incyte, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AbbVie, CBT Pharmaceuticals, Kadmon

Research Funding: Novartis (Inst), TRACON Pharma, Novocure (Inst), Spectrum Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Eli Lilly/ImClone (Inst), Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst)

Osaama H. Khan

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: NICO BrainPath

Anthony L. Asher

Stock or Other Ownership: Cryoport

Consulting or Advisory Role: Globus

Jeffrey S. Wefel

Consulting or Advisory Role: Angiochem (Inst), Bayer, Juno Therapeutics, Novocure, Genentech, Vanquish Oncology

Vinai Gondi

Honoraria: UpToDate

Consulting or Advisory Role: INSYS Therapeutics, AbbVie

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Novocure

REFERENCES

- 1.Chao JH, Phillips R, Nickson JJ: Roentgen-ray therapy of cerebral metastases. Cancer 7:682-689, 1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sperduto PW, Yang TJ, Beal K, et al. : Estimating survival in patients with lung cancer and brain metastases: An update of the graded prognostic assessment for lung cancer using molecular markers (lung-molGPA). JAMA Oncol 3:827-831, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown PD, Jaeckle K, Ballman KV, et al. : Effect of radiosurgery alone vs radiosurgery with whole brain radiation therapy on cognitive function in patients with 1 to 3 brain metastases: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 316:401-409, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulvenna P, Nankivell M, Barton R, et al. : Dexamethasone and supportive care with or without whole brain radiotherapy in treating patients with non-small cell lung cancer with brain metastases unsuitable for resection or stereotactic radiotherapy (QUARTZ): Results from a phase 3, non-inferiority, randomised trial. Lancet 388:2004-2014, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chidel MA, Suh JH, Reddy CA, et al. : Application of recursive partitioning analysis and evaluation of the use of whole brain radiation among patients treated with stereotactic radiosurgery for newly diagnosed brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 47:993-999, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shehata MK, Young B, Reid B, et al. : Stereotatic radiosurgery of 468 brain metastases < or =2 cm: Implications for SRS dose and whole brain radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 59:87-93, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aoyama H, Shirato H, Tago M, et al. : Stereotactic radiosurgery plus whole-brain radiation therapy vs stereotactic radiosurgery alone for treatment of brain metastases: A randomized controlled trial. [see comment] JAMA 295:2483-2491, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kocher M, Soffietti R, Abacioglu U, et al. : Adjuvant whole-brain radiotherapy versus observation after radiosurgery or surgical resection of one to three cerebral metastases: Results of the EORTC 22952-26001 study. J Clin Oncol 29:134-141, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soffietti R, Kocher M, Abacioglu UM, et al. : A European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer phase III trial of adjuvant whole-brain radiotherapy versus observation in patients with one to three brain metastases from solid tumors after surgical resection or radiosurgery: Quality-of-life results. J Clin Oncol 31:65-72, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang EL, Wefel JS, Hess KR, et al. : Neurocognition in patients with brain metastases treated with radiosurgery or radiosurgery plus whole-brain irradiation: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 10:1037-1044, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sahgal A, Aoyama H, Kocher M, et al. : Individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCT) comparing stereotactic radiosurgery alone to SRS plus whole brain radiation therapy in patients with brain metastasis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 87:1187, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamamoto M, Serizawa T, Shuto T, et al. : Stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with multiple brain metastases (JLGK0901): A multi-institutional prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol 15:387-395, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Walsh JW, et al. : A randomized trial of surgery in the treatment of single metastases to the brain. [see comment] N Engl J Med 322:494-500, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, et al. : Postoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of single metastases to the brain: A randomized trial. [see comment] JAMA 280:1485-1489, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahajan A, Ahmed S, McAleer MF, et al. : Post-operative stereotactic radiosurgery versus observation for completely resected brain metastases: A single-centre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 18:1040-1048, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown PD, Ballman KV, Cerhan JH, et al. : Postoperative stereotactic radiosurgery compared with whole brain radiotherapy for resected metastatic brain disease (NCCTG N107C/CEC·3): A multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 18:1049-1060, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kępka L, Tyc-Szczepaniak D, Bujko K, et al. : Stereotactic radiotherapy of the tumor bed compared to whole brain radiotherapy after surgery of single brain metastasis: Results from a randomized trial. Radiother Oncol 121:217-224, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown PD, Brown CA, Pollock BE, et al. : Stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with “radioresistant” brain metastases. Neurosurgery 51:656-665, discussion 665-667, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khuntia D, Brown P, Li J, et al. : Whole-brain radiotherapy in the management of brain metastasis. J Clin Oncol 24:1295-1304, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown PD: Whole brain radiotherapy for brain metastases. BMJ 355:i6483, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gondi V, Pugh SL, Tome WA, et al. : Preservation of memory with conformal avoidance of the hippocampal neural stem-cell compartment during whole-brain radiotherapy for brain metastases (RTOG 0933): A phase II multi-institutional trial. J Clin Oncol 32:3810-3816, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sul J, Kluetz PG, Papadopoulos EJ, et al. : Clinical outcome assessments in neuro-oncology: A regulatory perspective. Neuro-Oncology Practice 3:4-9, 2016. 10.1093/nop/npv062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeAngelis LM, Delattre JY, Posner JB: Radiation-induced dementia in patients cured of brain metastases. Neurology 39:789-796, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen HS, Pellegrini JW, Aggarwal SK, et al. : Open-channel block of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) responses by memantine: Therapeutic advantage against NMDA receptor-mediated neurotoxicity. J Neurosci 12:4427-4436, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen HS, Lipton SA: Mechanism of memantine block of NMDA-activated channels in rat retinal ganglion cells: Uncompetitive antagonism. J Physiol 499:27-46, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orgogozo JM, Rigaud AS, Stöffler A, et al. : Efficacy and safety of memantine in patients with mild to moderate vascular dementia: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial (MMM 300). Stroke 33:1834-1839, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilcock G, Möbius HJ, Stöffler A: A double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre study of memantine in mild to moderate vascular dementia (MMM500). Int Clin Psychopharmacol 17:297-305, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown PD, Pugh S, Laack NN, et al. : Memantine for the prevention of cognitive dysfunction in patients receiving whole-brain radiotherapy: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neuro-oncol 15:1429-1437, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rapp SR, Case LD, Peiffer A, et al. : Donepezil for irradiated brain tumor survivors: A phase III randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 33:1653-1659, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sahgal A, Ruschin M, Ma L, et al. : Stereotactic radiosurgery alone for multiple brain metastases? A review of clinical and technical issues. Neuro-oncol 19(suppl_2):ii2-ii15, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venur VA, Ahluwalia MS: Targeted therapy in brain metastases: Ready for primetime? Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 35:e123-e130, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welsh JW, Komaki R, Amini A, et al. : Phase II trial of erlotinib plus concurrent whole-brain radiation therapy for patients with brain metastases from non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 31:895-902, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ceresoli GL, Cappuzzo F, Gregorc V, et al. : Gefitinib in patients with brain metastases from non-small-cell lung cancer: A prospective trial. Ann Oncol 15:1042-1047, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mok TS, Wu Y-L, Ahn M-J, et al. : Osimertinib or platinum-pemetrexed in EGFR T790M-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med 376:629-640, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Costa DB, Shaw AT, Ou SH, et al. : Clinical experience with crizotinib in patients with advanced ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer and brain metastases. J Clin Oncol 33:1881-1888, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dummer R, Goldinger SM, Turtschi CP, et al. : Vemurafenib in patients with BRAF(V600) mutation-positive melanoma with symptomatic brain metastases: Final results of an open-label pilot study. Eur J Cancer 50:611-621, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McArthur GA, Maio M, Arance A, et al. : Vemurafenib in metastatic melanoma patients with brain metastases: An open-label, single-arm, phase 2, multicentre study. Ann Oncol 28:634-641, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davies MA, Saiag P, Robert C, et al. : Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with BRAF(V600)-mutant melanoma brain metastases (COMBI-MB): A multicentre, multicohort, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 18:863-873, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Margolin K, Ernstoff MS, Hamid O, et al. : Ipilimumab in patients with melanoma and brain metastases: An open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 13:459-465, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bachelot T, Romieu G, Campone M, et al. : Lapatinib plus capecitabine in patients with previously untreated brain metastases from HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (LANDSCAPE): A single-group phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 14:64-71, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin NU, Diéras V, Paul D, et al. : Multicenter phase II study of lapatinib in patients with brain metastases from HER2-positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 15:1452-1459, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Freedman RA, Gelman RS, Wefel JS, et al. : Translational Breast Cancer Research Consortium (TBCRC) 022: A phase II trial of neratinib for patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer and brain metastases. J Clin Oncol 34:945-952, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoffknecht P, Tufman A, Wehler T, et al. : Efficacy of the irreversible ErbB family blocker afatinib in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI)-pretreated non-small-cell lung cancer patients with brain metastases or leptomeningeal disease. J Thorac Oncol 10:156-163, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gadgeel SM, Shaw AT, Govindan R, et al. : Pooled analysis of CNS response to alectinib in two studies of pretreated patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 34:4079-4085, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gadgeel SM, Gandhi L, Riely GJ, et al. : Safety and activity of alectinib against systemic disease and brain metastases in patients with crizotinib-resistant ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer (AF-002JG): Results from the dose-finding portion of a phase 1/2 study. Lancet Oncol 15:1119-1128, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crinò L, Ahn MJ, De Marinis F, et al. : Multicenter phase II study of whole-body and intracranial activity with ceritinib in patients with ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy and crizotinib: Results from ASCEND-2. J Clin Oncol 34:2866-2873, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim D-W, Tiseo M, Ahn M-J, et al. : Brigatinib (BRG) in patients (pts) with crizotinib (CRZ)-refractory ALK+ non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): First report of efficacy and safety from a pivotal randomized phase (ph) 2 trial (ALTA). J Clin Oncol 34, 2016. suppl; abstr 9007 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Freedman RA, Gelman RS, Melisko ME, et al. : TBCRC 022: Phase II trial of neratinib + capecitabine for patients (Pts) with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2+) breast cancer brain metastases (BCBM). J Clin Oncol 35, 2017. suppl; abstr 1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Long GV, Trefzer U, Davies MA, et al. : Dabrafenib in patients with Val600Glu or Val600Lys BRAF-mutant melanoma metastatic to the brain (BREAK-MB): A multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 13:1087-1095, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shonka N, Venur VA, Ahluwalia MS: Targeted treatment of brain metastases. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 17:37, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berghoff AS, Venur VA, Preusser M, et al. : Immune checkpoint inhibitors in brain metastases: From biology to treatment. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 35:e116-e122, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldberg SB, Gettinger SN, Mahajan A, et al. : Pembrolizumab for patients with melanoma or non-small-cell lung cancer and untreated brain metastases: Early analysis of a non-randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 17:976-983, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tawbi HA-H, Forsyth PAJ, Algazi AP, et al. : Efficacy and safety of nivolumab (NIVO) plus ipilimumab (IPI) in patients with melanoma (MEL) metastatic to the brain: Results of the phase II study CheckMate 204. J Clin Oncol 35, 2017. suppl; abstr 9507 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Magnuson WJ, Yeung JT, Guillod PD, et al. : Impact of deferring radiation therapy in patients with epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant non-small cell lung cancer who develop brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 95:673-679, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kroeze SG, Fritz C, Hoyer M, et al. : Toxicity of concurrent stereotactic radiotherapy and targeted therapy or immunotherapy: A systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev 53:25-37, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner AA, et al. : Maintenance therapy with tumor-treating fields plus temozolomide vs temozolomide alone for glioblastoma: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 314:2535-2543, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kirson ED, Dbalý V, Tovarys F, et al. : Alternating electric fields arrest cell proliferation in animal tumor models and human brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:10152-10157, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, et al. : Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med 4:1313-1317, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Monje ML, Mizumatsu S, Fike JR, et al. : Irradiation induces neural precursor-cell dysfunction. Nat Med 8:955-962, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, et al. : Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 377:829-838, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]