Abstract

Purpose

Treatment of advanced non–small-cell lung cancer with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) is characterized by durable responses and improved survival in a subset of patients. Clinically available tools to optimize use of ICIs and understand the molecular determinants of response are needed. Targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) is increasingly routine, but its role in identifying predictors of response to ICIs is not known.

Methods

Detailed clinical annotation and response data were collected for patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer treated with anti–programmed death-1 or anti–programmed death-ligand 1 [anti-programmed cell death (PD)-1] therapy and profiled by targeted NGS (MSK-IMPACT; n = 240). Efficacy was assessed by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1, and durable clinical benefit (DCB) was defined as partial response/stable disease that lasted > 6 months. Tumor mutation burden (TMB), fraction of copy number–altered genome, and gene alterations were compared among patients with DCB and no durable benefit (NDB). Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed for 49 patients to compare quantification of TMB by targeted NGS versus WES.

Results

Estimates of TMB by targeted NGS correlated well with WES (ρ = 0.86; P < .001). TMB was greater in patients with DCB than with NDB (P = .006). DCB was more common, and progression-free survival was longer in patients at increasing thresholds above versus below the 50th percentile of TMB (38.6% v 25.1%; P < .001; hazard ratio, 1.38; P = .024). The fraction of copy number–altered genome was highest in those with NDB. Variants in EGFR and STK11 associated with a lack of benefit. TMB and PD-L1 expression were independent variables, and a composite of TMB plus PD-L1 further enriched for benefit to ICIs.

Conclusion

Targeted NGS accurately estimates TMB and elevated TMB further improved likelihood of benefit to ICIs. TMB did not correlate with PD-L1 expression; both variables had similar predictive capacity. The incorporation of both TMB and PD-L1 expression into multivariable predictive models should result in greater predictive power.

INTRODUCTION

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have dramatically changed the therapeutic landscape for patients with a multitude of advanced cancers, including non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC).1-6 Because only a subset of patients with lung cancer respond to ICIs, an urgent need exists to develop clinically practical tools to identify the subset of patients most likely to derive clinical benefit.

To date, the only Food and Drug Administration–approved predictive biomarkers are mismatch repair deficiency,7 and specifically in NSCLC, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression.6 Most trials in NSCLC have demonstrated increased response rates in tumors with greater PD-L1 expression, but enrichment of responses is incomplete.1,6 Our group and others have demonstrated that a greater somatic mutation burden is associated with a greater likelihood of response to immunotherapy in several tumor types, including melanoma,8,9 bladder cancer,10 NSCLC,11,12 and mismatch repair–deficient tumors.7,13 These studies established the importance of tumor mutation burden (TMB) as a biomarker that may be relevant across tumor types. However, most studies have used whole-exome sequencing (WES) to quantify TMB, a methodology that is not currently feasible or expedient at the scale of a clinical setting. By contrast, genomic profiling of tumors by using targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) is increasingly routine. At Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), a custom hybridization capture-based NGS assay (Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets [MSK-IMPACT])14 has been used to analyze > 10,000 tumors.15

We hypothesized that TMB determined by targeted NGS may associate with response to immunotherapy in patients with NSCLC. To address this hypothesis, we examined 240 patients with NSCLC profiled by targeted NGS and who were treated with anti–PD-1 or anti–PD-L1 [anti–PD-(L)1]–based therapy. A subset of tumors from these patients also were analyzed by WES to examine the correlation of TMB derived by both methods. Secondary analyses included an examination of associations of other molecular features obtained from targeted NGS, such as copy number alterations and specific genes, with response or resistance to ICIs as well as the relationship between TMB and PD-L1 expression.

METHODS

Patients

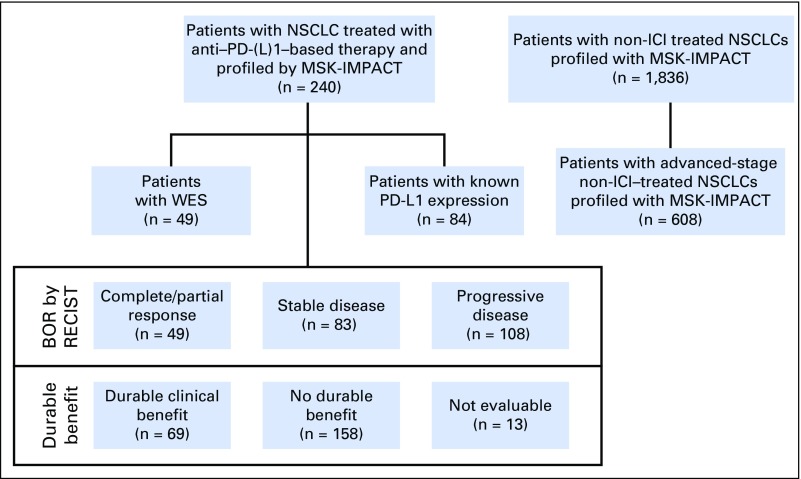

After MSKCC institutional review board approval, patients with advanced NSCLC treated with anti–PD-(L)1 monotherapy or in combination with anti–cytotoxic T-cell lymphocyte-4 (anti–CTLA-4) between April 2011 (the first date on which a patient with NSCLC was treated with ICI at our center) and January 2017 (the last date to have begun therapy to permit enough time for at least one response assessment before database lock in May 2017) were identified. Patients with tumors molecularly profiled by MSK-IMPACT were included. A prespecified sample size was not determined. Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 was used to assess efficacy; scans were reviewed by a thoracic radiologist (D.H., A.P., or N.L.) prospectively in patients treated as part of clinical trials or retrospectively in patients treated outside a clinical trial (Appendix Fig A1, online only). Patients who were not evaluable radiologically were excluded. Progression-free survival (PFS) was assessed from the date the patient began immunotherapy to the date of progression. Patients who had not progressed were censored at the date of their last scan; cases retrospectively adjudicated to not be progressive disease (PD) per RECIST but determined in real-time by the treating clinician as PD were considered as events. In addition to response defined by RECIST, efficacy also was defined as durable clinical benefit (DCB; complete response [CR]/partial response [PR] or stable disease [SD] that lasted > 6 months) or no durable benefit (NDB, PD or SD that lasted ≤ 6 months12; Appendix Fig A2, online only). Patients who had not progressed and were censored before 6 months of follow-up were considered not evaluable. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from treatment start date. Patients who did not die were censored at the date of last contact.

To provide a comparison cohort, patients with NSCLC who had undergone MSK-IMPACT testing between January 2014 and March 2017 and were not treated with any immunotherapy (non-ICI NSCLC; n = 1,836) were identified. For comparisons specifically related to OS, which was calculated from the date of recurrent or metastatic disease, a subset of these patients with non-ICI NSCLC with advanced-stage lung adenocarcinoma (non-ICI advanced stage; n = 60816) were used (Appendix Fig A1).

MSK-IMPACT Sequencing

The MSK-IMPACT assay was performed as previously described.14 Briefly, DNA was extracted from tumors and patient-matched blood samples. Bar-coded libraries were generated and sequenced and targeted all exons and select introns of a custom gene panel of 341 (56 patients; version 1), 410 (164 patients; version 2), or 468 (20 patients, version 3) genes (Appendix Table A1, online only). Mean sequencing coverage across all tumor samples was 744×, with minimum depth of coverage of 91×. Samples were run through a custom pipeline14 to identify somatic alterations, including mutations and copy number alterations. Data are available through the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics.17 To normalize somatic nonsynonymous TMB across panels of various sizes, the total number of mutations was divided by the coding region captured in each panel, which covered 0.98, 1.06, and 1.22 megabases (Mb) in the 341-, 410-, and 468-gene panels, respectively (Appendix Fig A3, online only). The fraction of copy number–altered genome (FGA) was defined as the fraction of genome with log2 copy number gain > 0.2 or loss < −0.2 relative to the size of the genome with copy number profiled. Tumor samples used for MSK-IMPACT were collected before immunotherapy treatment in 204 patients (85%; Appendix Table A2, online only).

Gene and Pathway Analysis

Individual genes were queried for enrichment among groups of DCB, NDB, and non-ICI NSCLC. Analysis included both previously described oncogenic or likely oncogenic variants as reported by OncoKB18 and variants of unknown significance. Reported percentages include all variants unless otherwise noted. Slides for one patient were stained for immunohistochemistry (IHC) with β2 microglobulin (B2M; polyclonal, 1 μg/mL; DAKO, Copenhagen, Denmark) on a BOND RX (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) after 30 minutes of antigen retrieval in Leica ER2 buffer by Bond Polymer Refine Detection.

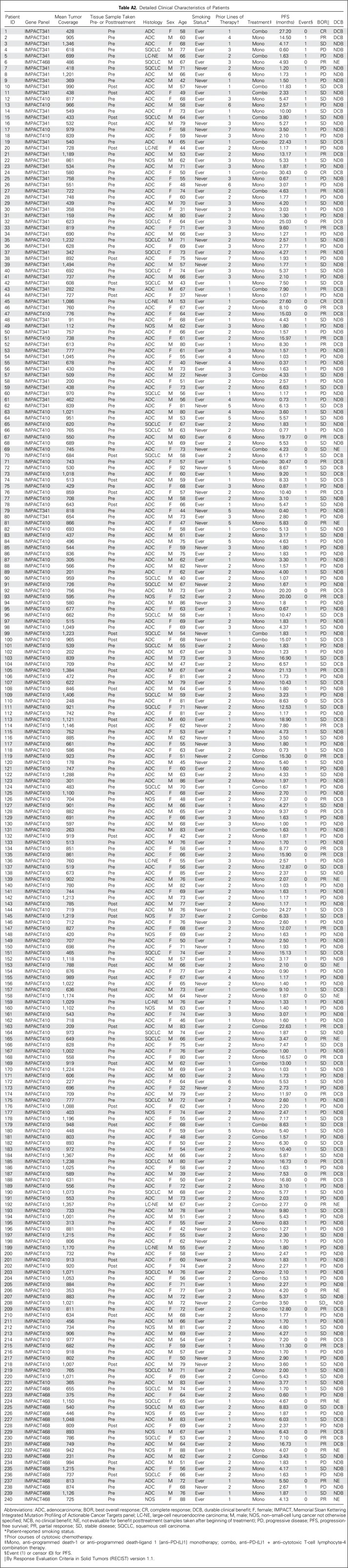

WES

A subset of patients (n = 49) had tumor/normal tissue profiled by both MSK-IMPACT and WES. The same tissue sample was used for both analyses in 40 patients; 36 were from the same DNA aliquot. Enriched exome libraries were sequenced on a HiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA) to generate paired-end reads (2 × 76 base pairs) to a target of 150× mean coverage (44 sequenced at Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA; five sequenced at MSKCC). The mean target coverage was 232× in tumor and 125× in normal sequences; mean target coverage < 60× in tumor or < 30× in normal sequences were excluded. For each patient, a binary alignment map file was produced by aligning tumor and normal sequences to the b37 human genome build with decoy contigs added. Additional indel realignment, base-quality score recalibration, and duplicate-read removal were performed by using the Genome Analysis Toolkit.19 MuTect was used to generate single-nucleotide variant (SNV) calls by using slightly modified default parameters20 (Appendix Table A3, online only). The complete listing of the source code for the variant detection pipeline is available online.21 The Genome Analysis Toolkit HaplotypeCaller was used to detect indels.22

PD-L1 Testing

Eighty-four tumors had tissue evaluated for PD-L1 expression, which was reported as the percentage of tumor cells with membranous staining. Several antibodies, which have largely been shown to be similar,23 were used, including 22C3 (n = 24; DAKO), 28-8 (n = 10; DAKO), and E1L3N (n = 50; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA).

Statistical Analysis

Differences in TMB and FGA were examined by using the Mann-Whitney U test for two-group comparisons or the Kruskal-Wallis exact test for three-group comparisons. The Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportions. For survival analyses, Kaplan-Meier curves were compared by using the log-rank test, and hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated by using the Mantel-Haenszel test. Correlations were examined by the Spearman rank correlation coefficients. Receiver operating characteristic curves that plotted sensitivity and 1-specificity of continuous variables and rate of DCB were assessed by generating the area under the curve (AUC). An unbiased analysis of enrichment in frequency of altered genes within individual groups were examined by plotting the log2(odds ratio) versus log2(Fisher’s exact test P value). The top 50 genes ordered by increasing P values were reported, with significant associations after correcting for the false discovery rate (FDR) highlighted. All reported P values are two-sided. All statistical analyses were performed with R version 3.3.3 software (www.r-project.org).

RESULTS

Mutation Burden and Somatic Molecular Features Associated With Immunotherapy Benefit

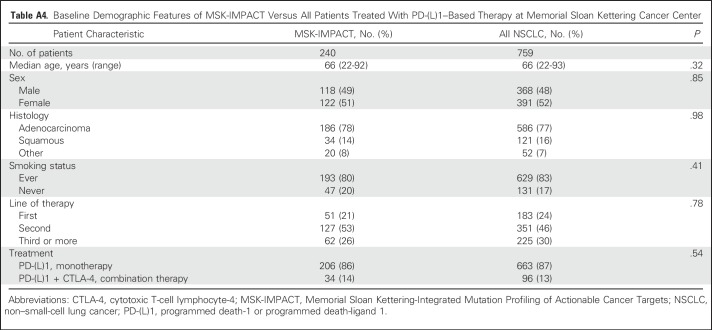

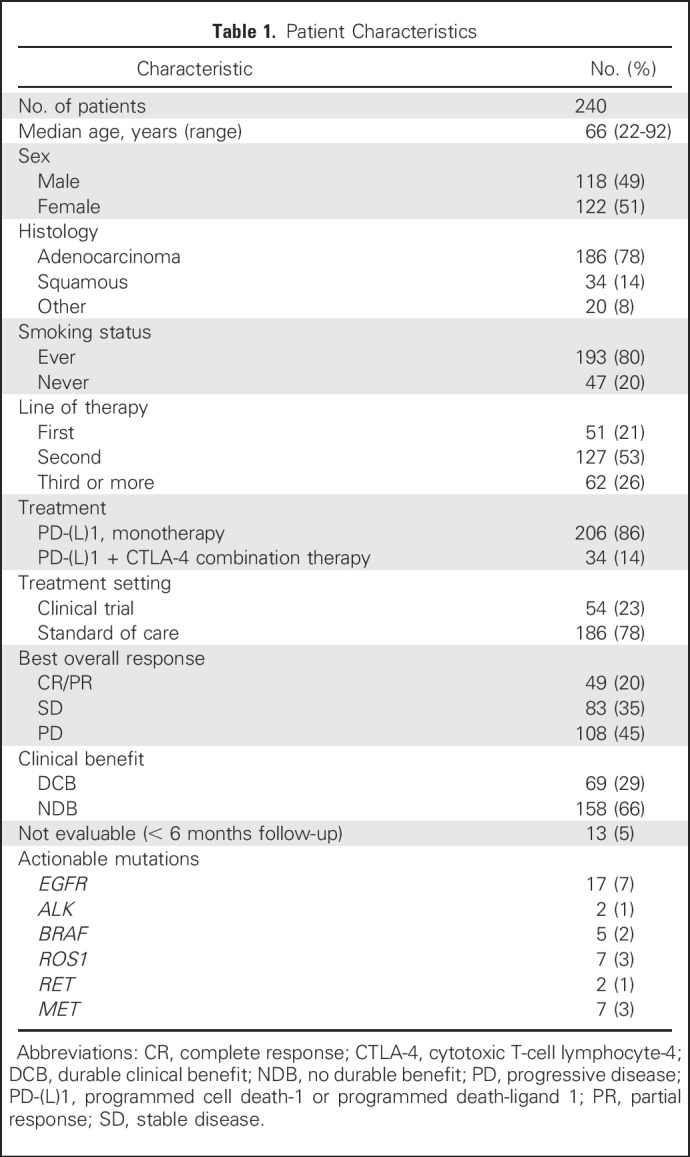

Since 2011, 759 patients with NSCLC have been treated with anti–PD-(L)1 therapy alone or in combination with anti–CTLA-4 therapy at MSKCC, of whom 398 (52%) have been profiled by MSK-IMPACT. Of these, 240 (60% of those molecularly profiled, 32% of all patients treated) were radiologically evaluable for response and are included in this analysis. Demographic features of the current patient cohort (Table 1) are similar to the overall group of patients treated with anti–PD-(L)1 therapy (Appendix Table A4, online only). Forty-nine patients (20%) had CR/PR; 69 (29%) had DCB. The median TMB was 7.4 SNVs/Mb (range, 0.8 to 91.8 SNVs/Mb).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

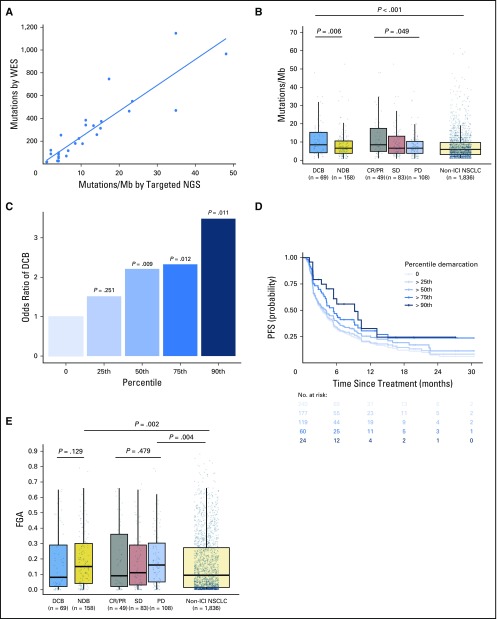

To determine whether targeted NGS could accurately quantitate TMB in NSCLC, we compared TMB quantified by MSK-IMPACT and WES in a subset of patients. In patients profiled with both targeted NGS and WES (n = 49), TMB assessed by targeted NGS was highly correlated with TMB assessed by WES (Spearman ρ = 0.86; P < .001; Fig 1A). By using data from targeted NGS, TMB was greater in patients with DCB than with NDB (median, 8.5 v 6.6 SNVs/Mb; P = .0062) and in patients with CR/PR versus SD versus PD (median, 8.5 v 6.6 v 6.6 SNVs/Mb; P = .0151; Fig 1B).

Fig 1.

Somatic molecular features associated with response to immunotherapy. (A) Tumor mutation burden (TMB) assessed by targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) correlates with TMB assessed by whole-exome sequencing (WES; n = 49, Spearman ρ = 0.86; P, .001). Individual tumors are shown as dots. The line depicts the best fit. (B) Somatic nonsynonymous TMB is greater in durable clinical benefit (DCB) versus no durable benefit (NDB; median, 8.5 v 6.6 single-nucleotide variants/megabase [Mb]; P = .006) and is significantly different in those with complete response (CR)/partial response (PR) versus stable disease (SD) versus progressive disease (PD; median, 8.5 v 6.6 v 6.6 single-nucleotide variants/Mb; P = .049). The distribution of TMB in patients with non–immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)–treated non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) are shown for reference. TMB in patients with DCB was similar to those with CR/PR (P = .85) and greater in those with non-ICI NSCLC (P, .001). Box plots represent medians, interquartile ranges, and vertical lines extend to the 95th percentiles. TMB of individual patients are represented with light dots. (C) Odds ratio (OR) of DCB with increasing cut points of TMB.25th (OR, 1.75), 50th (OR, 2.02), 75th (OR, 2.06), and 90th (OR, 3.24) percentiles. The 0 percentile (white bar) is shown for reference of all patients (default OR, 1). The odds of DCB increase significantly above the 50th percentile of TMB. (D) Individual Kaplan-Meier curves of progressionfree survival (PFS) above each percentile at increasing thresholds of TMB. PFS in patients with NSCLC treated with anti–programmed cell death-1– or anti–programmed deathligand 1–based therapy increaseswith increases inTMB. (E) Fraction of copy number–altered genome (FGA) inDCBversusNDB(median, 0.08 v 0.15;P = .129) and PR/CR versus SD versus PD (median, 0.09 v 0.11 v 0.16; P = .479). FGA is enriched among those with PD or NDB compared with non-ICI NSCLC (P = .004 and .002, respectively).

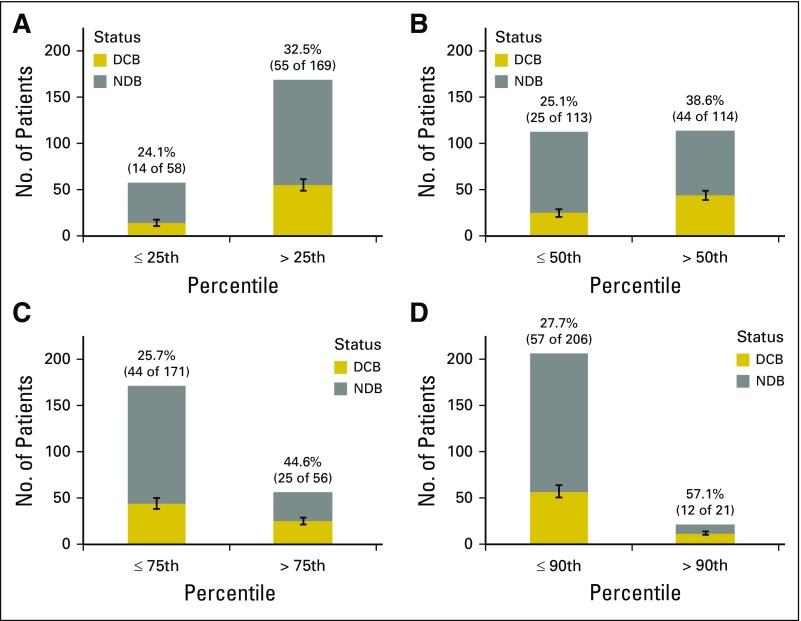

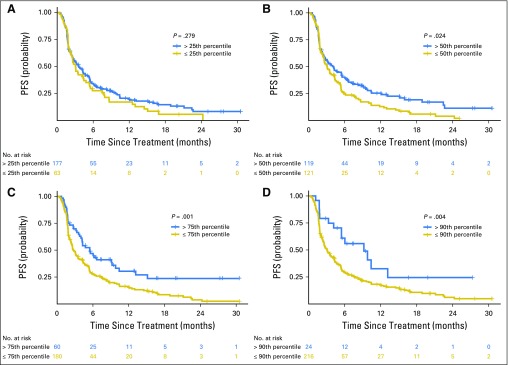

We examined how increasing cut points of TMB affected rates of DCB and PFS to ICI treatment. When TMB was stratified into increasing quartiles, rates of DCB and PFS improved with increasing TMB (Figs 1C and 1D); improved DCB rate and PFS were seen in those with TMB above versus below the 50th percentile (DCB rate, 38.6% v 25.1%; P = .009 [Appendix Fig A4, online only]; PFS HR, 1.38; P = .024 [Appendix Fig A5, online only]). The rate of DCB and PFS were also improved among those in the top decile of TMB in the cohort (Figs 1C and 1D). By contrast, survival outcomes among patients with advanced NSCLC not treated with immunotherapy16 did not correlate with increasing TMB; in fact, an inverse relationship between TMB and survival was identified (Appendix Fig A6, online only).

In addition, FGA was lowest in patients with DCB and significantly higher in those with NDB than in those with non-ICI NSCLC (median, 0.16 v 0.11; P = .007; Fig 1E). Of note, despite a negative association with response to ICIs, FGA had a modest but significantly positive association with TMB (Appendix Fig A7, online only).

Gene Alterations Associated With Response and Resistance to Immunotherapy

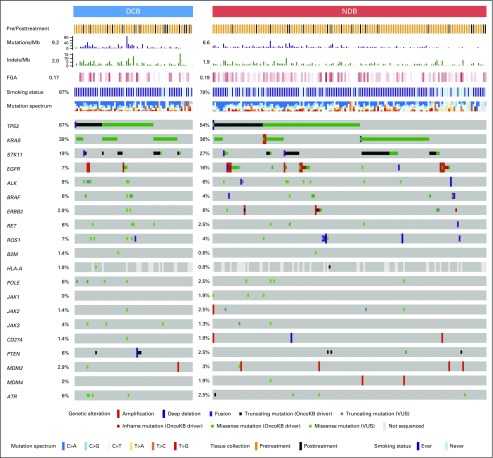

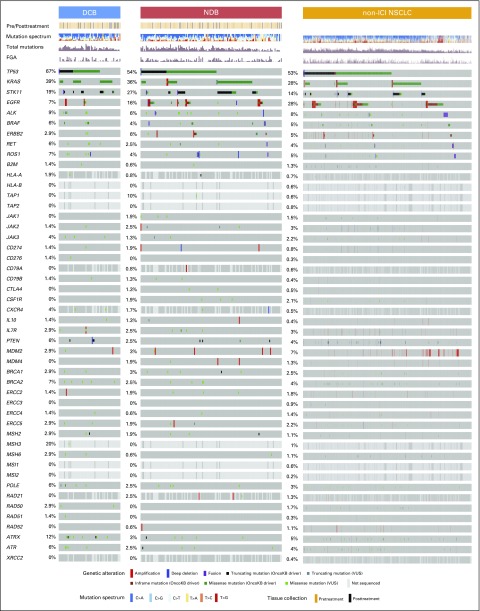

We next assessed whether mutations in individual genes were associated with response or resistance to ICI treatment. First, we examined the frequency of common oncogenic driver mutations found in NSCLC and their association with clinical benefit from ICI treatment.24 Mutations in KRAS were common (n = 83), and the rate of DCB was similar in this group compared with the overall study cohort (36%; Fig 2). Those with EGFR mutations rarely experienced DCB (7%) and were significantly underrepresented in the DCB group compared with the non-ICI NSCLC group (FDR-adjusted P = .013 Appendix Fig A8, online only). STK11 was significantly enriched in the NDB group compared with the non-ICI NSCLC group (FDR-adjusted P = .007).

Fig 2.

Genes associated with response and resistance to immunotherapy. OncoPrint that depicts alterations in preselected genes of interest in durable clinical benefit (DCB) and no durable benefit (NDB) groups. Reported frequencies include a composite of all alterations for each gene across all groups (single-nucleotide variants, indels, fusions, amplifications, deletions). Predicted functional impact of genetic alterations are described as known in OncoKB or variants of unknown significance (VUSs). Summary rows of each case at top include annotation for whether samples were obtained before or after initiation of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy, mutations/megabase (Mb; histogram), indels/Mb (histogram), frequencies of fraction of copy number–altered genome (FGA; lowest to highest FGA, white to dark red), smoking, and mutation spectrum. Events where information is unknown (eg, gene not covered in panel tested) are depicted in light gray on the OncoPrint.

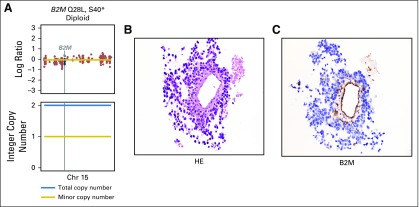

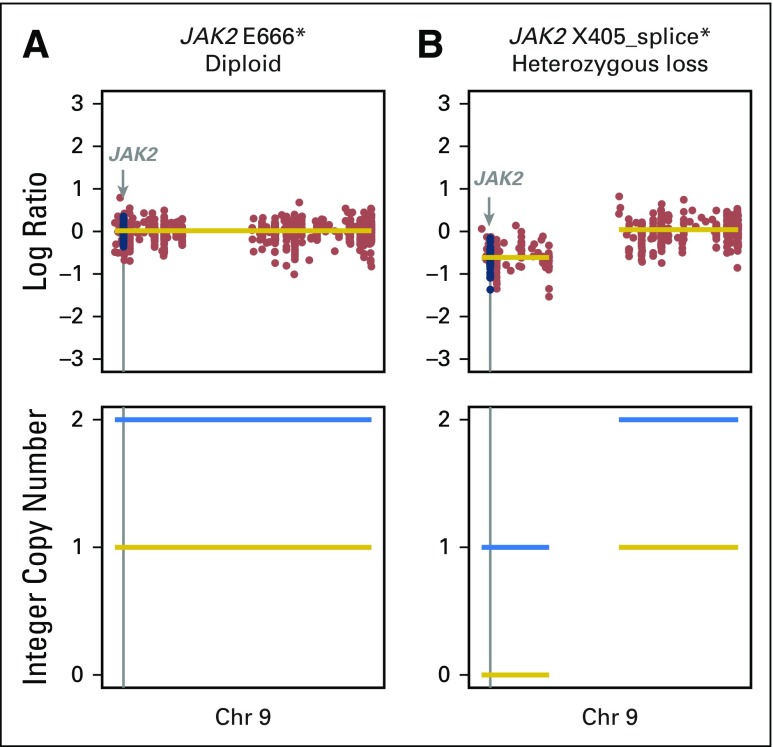

We also examined the prevalence and impact of alterations in genes associated with antigen presentation on response to immunotherapy (Fig 2; Appendix Fig A9, online only). Truncating mutations in the gene encoding B2M and deleterious mutations in JAK1 and JAK2 have recently been identified as mechanisms that lead to primary and acquired resistance to anti–PD-1 treatment in melanoma.7,25,26 In the current cohort, likely deleterious B2M mutations were rare, occurring in only one patient who had an S40* mutation in trans with a Q28L mutation of uncertain significance and loss of B2M expression in tumor cells by IHC (Appendix Fig A10, online only). As of August 2017, this patient has achieved an early response to PD-1 therapy that has been ongoing for 8.9 months. Mutations in JAK2 also were uncommon (n = 2), with only one tumor having a homozygous deleterious mutation (a loss-of-function splice mutation on one allele paired with loss of heterozygosity; Appendix Fig A11, online only); this patient had PD.

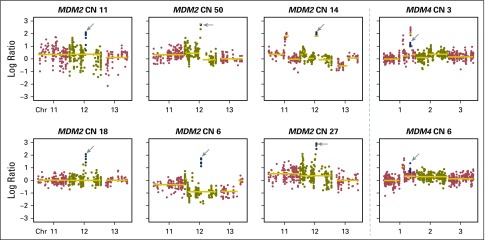

Recently, hyperprogression with anti–PD-1 therapy27 has been reported in patients treated with ICI and was associated with MDM2/MDM4 amplifications.28 In the current series, MDM2/MDM4 amplifications were identified in eight patients (Appendix Fig A12, online only), and PFS was not substantially different in this group compared with the overall patient cohort (HR, 1.4; P = .44).

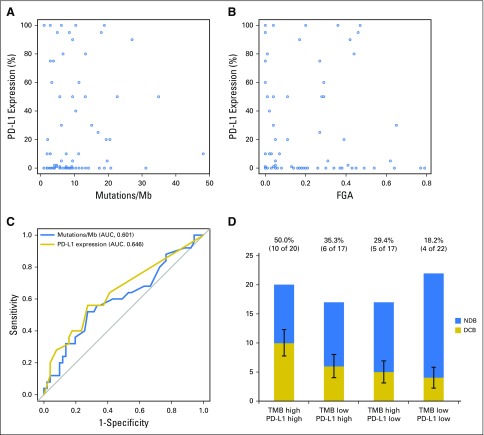

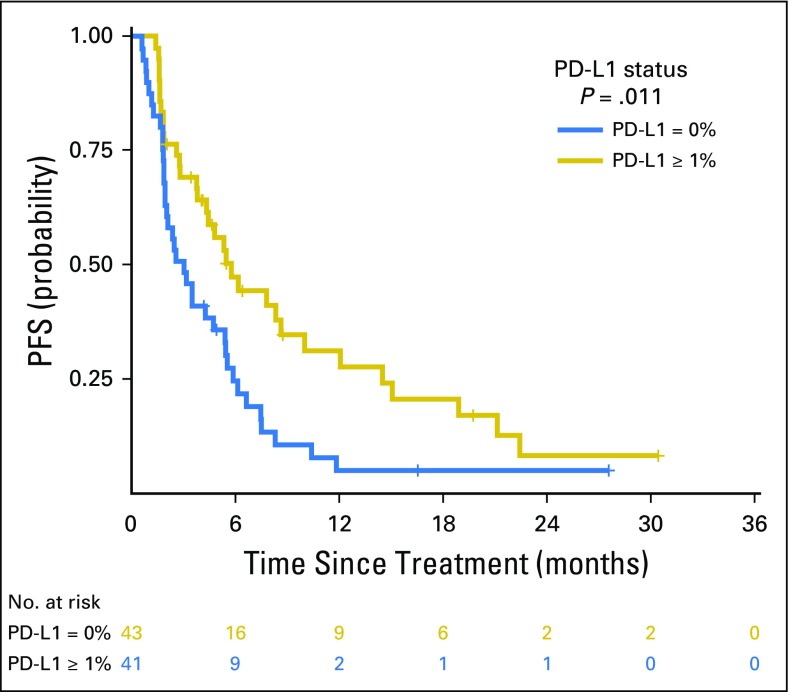

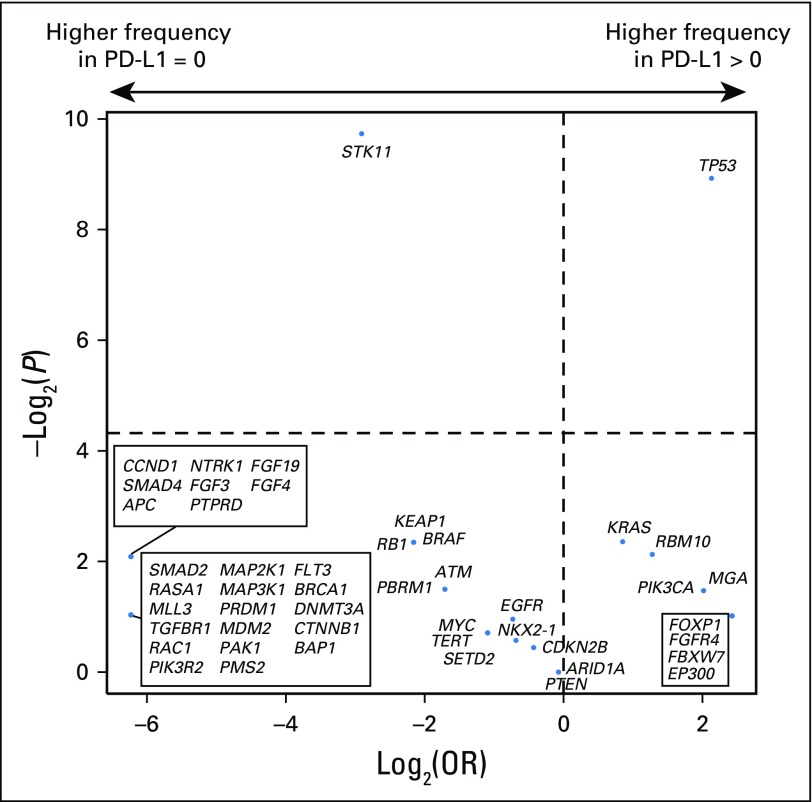

PD-L1 Expression and TMB

PD-L1 expression was available for 84 patients, of whom 43 (51%) had ≥ 1% expression. Consistent with prior reports, PD-L1 expression was associated with improved PFS (PD-L1, 0% v ≥ 1%; HR, 0.526; P = .011; Appendix Fig A13, online only). No correlation was found between PD-L1 and TMB (Spearman ρ = 0.1915; P = .08; Fig 3A) or PD-L1 and FGA (Spearman ρ = −0.1273; P = .25; Fig 3B). Considered as continuous variables, PD-L1 and TMB had a similar predictive impact on the likelihood of DCB (TMB AUC, 0.601; PD-L1 AUC, 0.646; Fig 3C). When considered as a composite variable, patients with high TMB (greater than the group median) and PD-L1 positivity (≥ 1% expression) had a 50% rate of DCB, whereas the presence of only one or neither variable was associated with a lower rate of DCB (Fig 3D). We also evaluated whether mutations in individual altered genes were associated with PD-L1 expression (stratified as ≥ 1% v < 1%; Appendix Fig A14, online only). SKT11 was the most enriched gene in the PD-L1–negative cohort, but this association was not statistically significant (FDR-adjusted P = .27).

Fig 3.

Comparison of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression with tumor mutation burden (TMB) and fraction of copy number–alteration genome (FGA). (A) Scatter plot of TMB and PD-L1 expression. TMB does not correlate with percent PD-L1 expression (n = 84; Spearman ρ = 0.192; P = .081). Dots represent individual tumors, and the line represents the best fit. (B) Scatter plot of FGA versus percent PD-L1 expression. No correlation exists between FGA and PD-L1 expression (n = 84; Spearman ρ = 0.127; P = .25). Dots represent individual tumors. (C) Receiver operating characteristic curve of sensitivity versus 1-specificity of durable clinical benefit (DCB) at varying levels of TMB (area under the curve [AUC], 0.601; P = .078) and PD-L1 expression (AUC, 0.646; P = .014). Results depict only those patients with available data for both TMB and PD-L1 (n = 84). (D) A histogram depicts the proportion of DCB among patients in groups defined by a composite variable of TMB (stratified above and below the median as low v high) and PD-L1 expression (stratified into 0% or ≥ 1% groups as low v high). Rate of DCB is lowest in patients low for both variables (18%), intermediate in patients high for one variable (29% to 35%), and highest in patients high for both variables (50%). Error bars show the SE of the percentage. Mb, megabase.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, we describe the largest series to date to explore the molecular determinants of response to ICIs and the first series to evaluate the role of molecular features derived from targeted NGS in determining response or resistance to anti–PD-(L)1–based therapy in patients with advanced NSCLC. TMB assessed by targeted NGS was significantly associated with improved benefit among patients with NSCLC treated with ICIs, with the odds of DCB improving with increasing thresholds. Because there was no positive correlation between increasing TMB and survival in a cohort of patients not treated with ICIs, we demonstrate that the effect of TMB is predictive rather than prognostic. In fact, survival among patients with high TMB is worse in the absence of ICI, which also highlights the clinical value of ICI to improve survival and overcome naturally poor prognostic features.

Although TMB has been a major focus of biomarker studies, other molecular features also have been hypothesized to influence the likelihood of clinical benefit from ICIs. Aneuploidy was shown recently to reduce response to immunotherapy in patients with melanoma.29,30 These reports largely focused on patients treated with CTLA-4 therapy and hypothesized that aneuploidy negatively correlates with the presence of cytotoxic immune infiltrates that may subsequently lead to poor survival outcomes in these patients. Similarly, we found that the FGA was highest among patients who derived the least benefit from ICIs. Despite this inverse association, FGA and TMB were modestly but positively associated with each other, consistent with a previous report.29 Given the growing concordance of data that support aneuploidy and lack of response to ICIs, additional work is needed to explore the underlying mechanism and impact of its interaction with TMB.

Beyond summary metrics, such as TMB and FGA, we also examined the impact of specific gene alterations on benefit from ICI. In an unbiased analysis, few additional genes were significantly associated with DCB and NDB. Mutations in EGFR were underrepresented among patients with DCB, which is likely related to the association of EGFR mutations with never smokers31 and resulting low TMB. Other actionable mutations in lung cancer also were found in low frequency in the current data set (Table 1). Future analysis is needed to clarify the activity of immunotherapy and whether TMB is similarly relevant in these patients. Alterations in STK11 also were associated with lack of benefit, which is consistent with recent reports that described low tumor inflammation in murine models and human tumors with STK11 alterations.32,33

We also explored specific alterations that have been previously purported to affect response to ICI. For example, amplifications in MDM2 and MDM4 have been associated with hyperprogression,27 although this was not seen in the current cohort. Separately, alterations in B2M and JAK2 have been described as mediating acquired resistance in patients with melanoma treated with PD-1 blockade.26 Although our study was not designed to examine acquired resistance (where selective pressure from ICI may increase the frequency of these variants), we identified one patient with a deleterious homozygous JAK2 mutation in a setting of primary resistance, consistent with cases of acquired resistance mediated through defective interferon gamma signaling.25,34 Of note, the one patient with two trans mutations in B2M and loss-of-protein expression confirmed by IHC has an ongoing PR to therapy and a mutation rate of 48 SNVs/Mb.

Overall, although MSK-IMPACT examines several hundred cancer-associated genes, we did not observe novel associations between mutation in individual genes and response or resistance to ICI, which may reflect that current targeted NGS panels were constructed for the purpose of identifying targetable oncogenes and, thus, may not include the key genetic determinants of immunotherapy response. However, because these panels can be readily amended to include additional probes to expand the genetic landscape surveyed (eg, the MSK-IMPACT panel has increased from 341 genes at inception to currently 468 genes), a future effort to include genes specifically related to immunogenomics is likely to be fruitful. In addition, continued emphasis on approaches such as WES and whole-genome sequencing for ongoing discovery is important.

One of the critiques of WES as a prospective tool for examining predictors of response to ICI to aid in clinical decision making is that it is not optimized for use in routine clinical practice. By contrast, the use of targeted NGS to guide treatment has become increasingly routine, particularly in patients with lung cancer.15,16,35 Furthermore, consistent with recent reports that analyzed the same patient tumors for targeted NGS and WES,15,35 we found that TMB quantified by targeted NGS closely correlated with TMB as quantified by WES. However, not all NGS panels may be well suited to estimate TMB; in particular, caution may be needed when using smaller panels. A recent report described that in panels with genomic coverage < 0.5 Mb, the accuracy of TMB determined by targeted NGS diminishes.35

Despite the consistent relevance of TMB and PD-L1 as predictive biomarkers of response to ICI across series, neither is fully sensitive or specific. We found that TMB and PD-L1 expression were independent variables that both associated with benefit as previously seen.11 It seems that TMB is similarly meaningful as PD-L1 expression, but a composite of both variables may be most helpful in identifying with precision patients most likely to benefit.

The current study had a moderate sample size, which may limit the power of conclusions, especially when considering multiple variables and subgroup analyses. Nonetheless, this analyzed cohort is representative of the overall patient population treated with ICI at our institution (Appendix Table A4). Although clinical outcomes were derived retrospectively in some patients, inclusion of both the clinical trial and the real-world clinical experience of patients who receive ICI makes results generalizable across various treatment settings. Finally, because this study used a single targeted NGS panel at our institution, the analysis does not attempt to specify a universally applicable cut point of TMB for derived benefit and instead highlights a trend that demonstrates an increase in benefit with increasing TMB. As a result of variations in panels as well as of differences in informatics methods, a relevant numerical cut point would need to be assay specific and distinct to specific clinical situations.

In conclusion, given the remarkable antitumor activity of ICIs coupled with advances in targeted sequencing approaches to routinely molecularly profile tumors, we determined the utility of targeted NGS in identifying patients who most benefit from ICI. We found that TMB determined by targeted NGS strongly correlates with TMB as determined by WES, is associated with clinical benefit, and is independent of PD-L1 expression with similar predictive capacity. Other molecular features derived from targeted NGS may also refine the predictive capacity of these tools. Moving forward, multiple orthogonal biomarkers, integrating DNA sequencing, transcriptomics,36 multiplexed protein expression,37 T-cell receptor clonality,38 and others will need to be considered together to realize more fully the potential for precision immunotherapy.

Appendix

Fig A1.

Flow of patients with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). These patients were treated with anti–programmed cell death-1 or anti–programmed death-ligand 1 [PD-(L)1] therapy from April 2011 through January 2017 and profiled with Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT) panels are shown on the left. Patients with NSCLC profiled with MSK-IMPACT who have not been treated with immunotherapy (non–immune checkpoint inhibitors [ICIs]) are shown on the right. BOR, best overall response; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; WES, whole-exome sequencing.

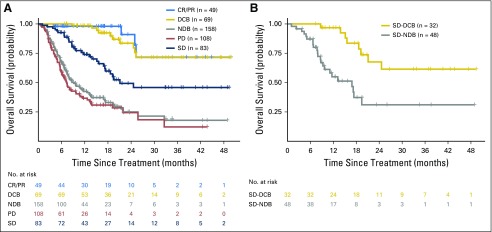

Fig A2.

Durable clinical benefit (DCB)/no durable benefit (NDB) compared with Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST)–defined benefit. DCB and NDB are clinically useful, simple, binary outcomes to categorize those who benefit or not from immunotherapy. These groups have survival outcomes similar to RECIST-defined complete response (CR)/partial response (PR) or progressive disease (PD) while also incorporating meaningful distinction of those with stable disease (SD) who are benefiters or not. (A) Overall survival of patients with DCB/NDB or CR/PR, SD, or PD. Survival of DCB closely mirrors that of CR/PR, and NDB mirrors patients with PD. (B) A focus just on patients with SD shows a significant difference in overall survival stratified by DCB and NDB (P < .001). RECIST-defined SD, therefore, is an intermediate group that is comprised by a “true” benefit (progression-free survival [PFS] > 6 months) and not a “true” benefit (PFS < 6 months). Therefore, dichotomizing outcomes by duration of benefit more explicitly captures the major contribution of benefit from immunotherapy (durability), removes patients with uncommon short-lived responses, and improves adjudication of those with RECIST-defined SD, a heterogeneous group that comprises true benefit or not of immunotherapy.

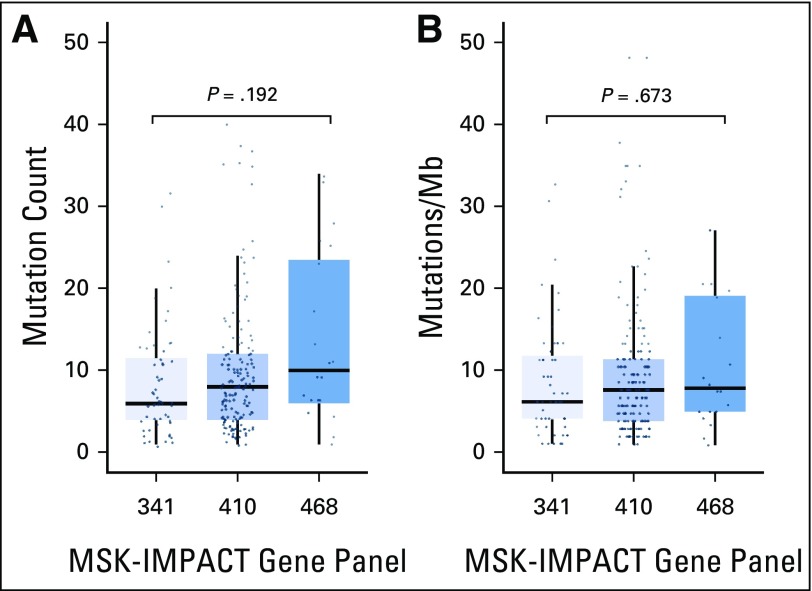

Fig A3.

Range of mutation burden across varying sizes of targeted next-generation sequencing panels. (A) Absolute nonsynonymous missense mutation count reported for tumors assessed by using the Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT) 341-, 410-, and 486-gene panels. Increasing absolute mutation burden is seen with increasing numbers of genes tested (median of six, eight, and nine and a half mutations in the 341-, 410-, and 486-gene panels, respectively; P = .192). (B) The mutation rate normalized by the size of the coding region covered. This correction results in similar mutation rates across each panel (median, 6.1, 7.5, and 7.8 per megabase [Mb] in the 341-, 410-, and 486-gene panels, respectively; P = .673).

Fig A4.

Proportion of durable clinical benefit (DCB) above or below the (A) 25th, (B) 50th, (C) 75th, and (D) 90th percentiles of tumor mutation burden. Percentages of DCB in each group are reported above each bar. Error bars show the SE of the percentage. NDB, no durable response.

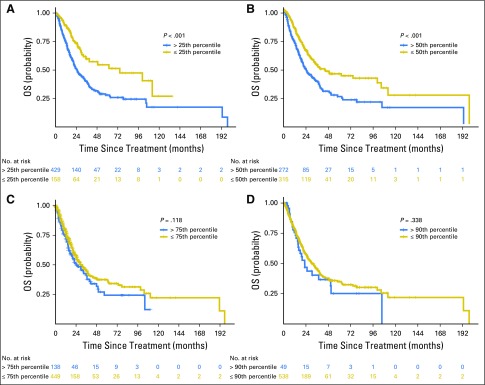

Fig A5.

Progression-free survival (PFS) of patients with tumor mutation burden above or below the (A) 25th, (B) 50th, (C) 75th, and (D) 90th percentiles. The hazard ratios for PFS at each cut point were as follows: 25th percentile, 1.19 (P = .279); 50th percentile, 1.38 (P = .024); 75th percentile, 1.74 (P = .001); 90th percentile, 2.05 (P = .004).

Fig A6.

Overall survival (OS) of patients with advanced-stage lung adenocarcinoma not treated with immunotherapy. Survival is shown on the basis of tumor mutation burden above or below the (A) 25th, (B) 50th, (C) 75th, and (D) 90th percentiles within the non–immune checkpoint inhibitor non–small-cell lung cancer advanced-stage cohort (n = 609). The hazard ratios for OS at each cut point were as follows: 25th percentile, 0.49 (P < .001); 50th percentile, 0.58 (P < .001); 75th percentile, 0.81 (P = .118); and 90th percentile, 0.82 (P = .338).

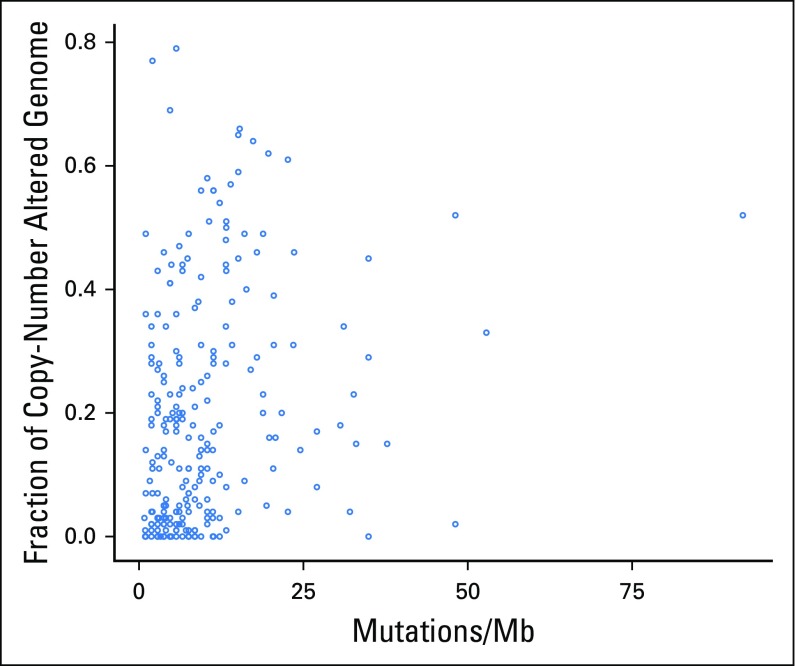

Fig A7.

Scatter plot of tumor mutational burden versus fraction of copy number–altered genome in individual tumors (n = 240; Spearman ρ = 0.31; P < .001). Mb, megabase.

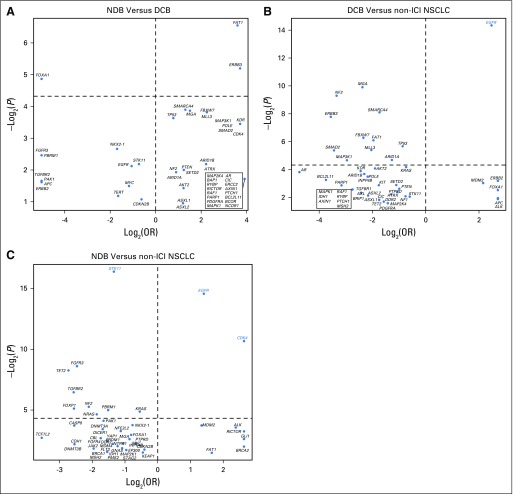

Fig A8.

Log2(odds ratio [OR]) and –log2(P value) for enrichment of individual altered genes deemed oncogenic or likely oncogenic by OncoKB in group comparisons of (A) durable clinical benefit (DCB) versus no durable benefit (NDB), (B) DCB versus non–immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and (C) NDB versus non-ICI NSCLC. The top 50 genes in each comparison are depicted, with adjusted P values used. Genes labeled in red were significantly enriched after correcting for the false discovery rate.

Fig A9.

OncoPrint that depicts durable clinical benefit (DCB), no durable benefit (NDB), and non–immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with an expanded list of preselected genes of interest, including oncogenic drivers in NSCLC, genes involved in antigen presentation, genes involved in modulating immune responses to cancer, genes previously reported to associate with response/resistance to programmed death-1 blockade, and genes involved in DNA repair. Genes shown in light gray were not sequenced as part of the MSK-IMPACT (Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets) panel. VUS, variant of unknown significance.

Fig A10.

β2 microglobulin (B2M) mutation found in one patient that occurred in trans with one mutation on each allele. (A) The top plot shows overall copy number segmentations across the chromosome (Chr), with the vertical line highlighting the B2M gene position. The bottom plot shows the integer copy number, with the black line depicting the total integer copy number and the red line depicting minor copy number. (B) The hematoxylin and eosin (HE) stain (magnification, ×40) shows large tumor cells circumferentially around a central vessel. (C) B2M immunohistochemistry (magnification, ×40) shows selective loss of expression in tumor cells with retention of expression in normal endothelium and within scattered lymphocytes and histiocytes.

Fig A11.

JAK2 mutations were found in two patients. (A) A heterozygous mutation in JAK2 with the wild-type allele retained. (B) A homozygous loss-of-function mutation in JAK2 with loss of the wild-type allele occurring in a patient with primary progression to programmed death-1 blockade. Chr, chromosome.

Fig A12.

Amplifications in MDM2 or MDM4 were found in eight patients. Each plot shows the copy number (CN) log ratio of the overall CN segmentations across chromosomes (Chr). Estimated integer CNs are reported for each patient and calculated by FACETS. One patient had durable clinical benefit and five of eight patients had > 2 months progression-free survival. The patient with the greatest amplification had rapid progression. The progression-free survival curve of patients with MDM2 or MDM4 amplifications are compared with those with MDM2/MDM4 wild type (hazard ratio, 1.4; P = .44).

Fig A13.

Progression-free survival (PFS) curve of patients with a programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression of 0% compared with a PD-L1 expression ≥ 1% (hazard ratio, 0.53; P = .01).

Fig A14.

Log2(odds ratio [OR]) and –log2(P value) for enrichment of individual altered genes deemed oncogenic or likely oncogenic by OncoKb in the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)–positive versus PD-L1–negative subgroup. The top 50 genes in each comparison are depicted, with the false discovery rate–adjusted P values used.

Table A1.

Gene Lists for MSK-IMPACT Versions 1 (341 Genes), 2 (410 Genes), and 3 (468 Genes)

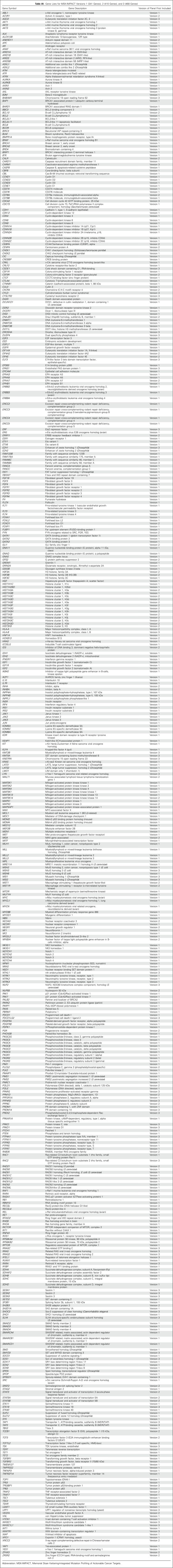

Table A2.

Detailed Clinical Characteristics of Patients

Table A3.

WES Metrics and Comparison With Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing

Table A4.

Baseline Demographic Features of MSK-IMPACT Versus All Patients Treated With PD-(L)1–Based Therapy at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

Footnotes

Supported by a Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support grant/core grant (P30 CA008748); a Conquer Cancer Foundation of ASCO Career Development Award; a Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center grant; a Society for Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center grant; the Center for Metastasis Research of the Sloan Kettering Institute; Swim Across America; Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research; Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy; and Druckenmiller Center for Lung Cancer Research at MSKCC. These investigators (TH, TM, JDW, MDH) are members of the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy. Research supported by a Stand Up to Cancer (SU2C)-American Cancer Society Lung Cancer Dream Team Translational research grant (SU2C-AACR-DT17-15). SU2C is a program of the Entertainment Industry Foundation. Research grants are administered by the American Association for Cancer Research, the scientific partner of SU2C. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of ASCO or the Conquer Cancer Foundation.

Presented in part at the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2017 Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, June 2-6, 2017.

See accompanying Editorial on page 631

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Hira Rizvi, Francisco Sanchez-Vega, Nikolaus Schultz, Matthew D. Hellmann

Financial support: David B. Solit, Matthew D. Hellmann

Administrative support: David B. Solit, Matthew D. Hellmann

Provision of study materials or patients: David B. Solit, Matthew D. Hellmann

Collection and assembly of data: Hira Rizvi, Francisco Sanchez-Vega, Konnor La, Philip Jonsson, Darragh Halpenny, Andrew Plodkowski, Niamh Long, Natasha Rekhtman, Travis Hollmann, Taha Merghoub, David B. Solit, Matthew D. Hellmann

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Molecular Determinants of Response to Anti–Programmed Cell Death (PD)-1 and Anti–Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) Blockade in Patients With Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Profiled With Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Hira Rizvi

No relationship to disclose

Francisco Sanchez-Vega

No relationship to disclose

Konnor La

No relationship to disclose

Walid Chatila

No relationship to disclose

Philip Jonsson

No relationship to disclose

Darragh Halpenny

No relationship to disclose

Andrew Plodkowski

No relationship to disclose

Niamh Long

No relationship to disclose

Jennifer L. Sauter

Stock or Other Ownership: Allergan, Celgene, Chemed, Express Scripts, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Mylan, Owens & Minor, Pfizer, Stryker, Thermo Fisher Scientific, iShares Nasdaq Biotech

Natasha Rekhtman

No relationship to disclose

Travis Hollmann

Research Funding: General Electric

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Leica Biosystems, Indica Laboratories, PerkinElmer

Kurt A. Schalper

Honoraria: Takeda Pharmaceuticals

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Shattuck Labs

Speakers’ Bureau: Merck

Research Funding: Vasculox, Tesaro, Onkaido Therapeutics, Genoptix, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Surface Oncology

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Fluidigm

Justin F. Gainor

Honoraria: Merck, Incyte, ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Novartis, Roche, Genentech

Consulting or Advisory Role: Clovis Oncology, Genentech, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Theravance, Loxo, Takeda Pharmaceuticals

Research Funding: Merck, Novartis, Genentech, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Adaptimmune, AstraZeneca, ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Jounce Therapeutics, Array BioPharma, Moderna Therapeutics

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Affymetrix

Ronglai Shen

No relationship to disclose

Ai Ni

No relationship to disclose

Kathryn C. Arbour

No relationship to disclose

Taha Merghoub

No relationship to disclose

Jedd Wolchok

Stock or Other Ownership: Potenza Therapeutics, Tizona Therapeutics, Serametrix, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Trieza Therapeutics, BeiGene

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, MedImmune, Polynoma, Polaris Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, F-Star, BeiGene, SELLAS Life Sciences, Eli Lilly, Tizona Therapeutics, Amgen, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Ascentage Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceuticals

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Roche (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Co-inventor on an issued patent for DNA vaccines for treatment of cancer in companion animals, co-inventor on a patent for use of oncolytic Newcastle disease virus

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Roche, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kadmon

Alexandra Snyder

No relationship to disclose

Jamie E. Chaft

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, MedImmune

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech, Roche, AstraZeneca, MedImmune, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb

Research Funding: Genentech (Inst), Roche (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), MedImmune (Inst)

Mark G. Kris

Honoraria: AstraZeneca

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca

Research Funding: Puma Biotechnology (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Roche (Inst)

Charles M. Rudin

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Elucida Oncology, Harpoon Therapeutics

Research Funding: BioMarin Pharmaceutical

Nicholas D. Socci

No relationship to disclose

Michael F. Berger

No relationship to disclose

Barry S. Taylor

No relationship to disclose

Ahmet Zehir

No relationship to disclose

David B. Solit

Honoraria: Loxo, Pfizer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Loxo

Maria E. Arcila

Honoraria: Invivoscribe

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Invivoscribe

Marc Ladanyi

Honoraria: Merck (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: National Comprehensive Cancer Network/Boehringer Ingelheim Afatinib Targeted Therapy Advisory Committee, National Comprehensive Cancer Network/AstraZeneca Tagrisso Request for Proposals Advisory Committee

Research Funding: Loxo (Inst)

Gregory J. Riely

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech

Research Funding: Novartis (Inst), Roche (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Takeda Pharmaceuticals (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), ARIAD Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Patent application submitted covering pulsatile use of erlotinib to treat or prevent brain metastases (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Novartis, Merck Sharp & Dohme

Nikolaus Schultz

No relationship to disclose

Matthew D. Hellmann

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Genentech, AstraZeneca, MedImmune, Novartis, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Mirati Therapeutics, Shattuck Labs

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Patent filed by MSK related to the use of tumor mutation burden to predict response to immunotherapy (PCT/US2015/062208).

REFERENCES

- 1.Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, et al. : Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 372:2018-2028, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. : Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 373:1627-1639, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. : Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 373:123-135, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fehrenbacher L, Spira A, Ballinger M, et al. : Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (POPLAR): A multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 387:1837-1846, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, et al. : Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 387:1540-1550, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. : Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 375:1823-1833, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, et al. : Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 357:409-413, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, et al. : Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med 371:2189-2199, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B, et al. : Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science 350:207-211, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits J, Powles T, et al. : Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: A single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet 387:1909-1920, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carbone DP, Reck M, Paz-Ares L, et al. : First-line nivolumab in stage IV or recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 376:2415-2426, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, et al. : Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science 348:124-128, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. : PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med 372:2509-2520, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, et al. : Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): A hybridization capture-based next-generation sequencing clinical assay for solid tumor molecular oncology. J Mol Diagn 17:251-264, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zehir A, Benayed R, Shah RH, et al. : Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med 23:703-713, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jordan EJ, Kim HR, Arcila ME, et al. : Prospective comprehensive molecular characterization of lung adenocarcinomas for efficient patient matching to approved and emerging therapies. Cancer Discov 7:596-609, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. CBioPortal for Cancer Genomics: Non-small-cell lung cancer (MSK, JCO 2018). http://www.cbioportal.org/study?id=nsclc_pd1_msk_2018.

- 18.Chakravarty D, Gao J, Phillips SM, et al. : OncoKB: A precision oncology knowledge base. Precision Oncol 2017:1-16, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cibulskis K, McKenna A, Fennell T, et al. : ContEst: Estimating cross-contamination of human samples in next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 27:2601-2602, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cibulskis K, Lawrence MS, Carter SL, et al. : Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol 31:213-219, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. GitHub: soccin/BIC-variants_pipeline. https://github.com/soccin/BIC-variants_pipeline.

- 22. Van der Auwera GA, Carneiro MO, Hartl C, et al: From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: The Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 43:11.10.1-11.10.33, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Rimm DL, Han G, Taube JM, et al. : A prospective, multi-institutional, pathologist-based assessment of 4 immunohistochemistry assays for PD-L1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol 3:1051-1058, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kris MG, Johnson BE, Berry LD, et al. : Using multiplexed assays of oncogenic drivers in lung cancers to select targeted drugs. JAMA 311:1998-2006, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shin DS, Zaretsky JM, Escuin-Ordinas H, et al. : Primary resistance to PD-1 blockade mediated by JAK1/2 mutations. Cancer Discov 7:188-201, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaretsky JM, Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS, et al. : Mutations associated with acquired resistance to PD-1 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med 375:819-829, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Champiat S, Dercle L, Ammari S, et al. : Hyperprogressive disease is a new pattern of progression in cancer patients treated by anti-PD-1/PD-L1. Clin Cancer Res 23:1920-1928, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato S, Goodman A, Walavalkar V, et al. : Hyperprogressors after immunotherapy: Analysis of genomic alterations associated with accelerated growth rate. Clin Cancer Res 23:4242-4250, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davoli T, Uno H, Wooten EC, et al. : Tumor aneuploidy correlates with markers of immune evasion and with reduced response to immunotherapy. Science 355:355, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roh W, Chen PL, Reuben A, et al. : Integrated molecular analysis of tumor biopsies on sequential CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade reveals markers of response and resistance. Sci Transl Med 9:9, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Govindan R, Ding L, Griffith M, et al. : Genomic landscape of non-small cell lung cancer in smokers and never-smokers. Cell 150:1121-1134, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koyama S, Akbay EA, Li YY, et al. : STK11/LKB1 deficiency promotes neutrophil recruitment and proinflammatory cytokine production to suppress T-cell activity in the lung tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res 76:999-1008, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skoulidis F, Byers LA, Diao L, et al. : Co-occurring genomic alterations define major subsets of KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma with distinct biology, immune profiles, and therapeutic vulnerabilities. Cancer Discov 5:860-877, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS, Moreno BH, et al. : Interferon receptor signaling pathways regulating PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression. Cell Reports 19:1189-1201, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chalmers ZR, Connelly CF, Fabrizio D, et al. : Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med 9:34, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ayers M, Lunceford J, Nebozhyn M, et al. : IFN-γ-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. J Clin Invest 127:2930-2940, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nghiem PT, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ, et al. : PD-1 Blockade with pembrolizumab in advanced Merkel-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 374:2542-2552, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, et al. : PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 515:568-571, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]