Introduction

Scientific progress in cancer has brought unprecedented growth in knowledge, which has challenged health care providers and researchers to ensure that clinical practice matches the best available evidence. But adoption of evidence into clinical cancer practice remains slow and uneven across geographic regions and care settings, which has led to unwarranted variations and deficiencies in quality of care.1 In 2013, the Institute of Medicine declared cancer care as a system in crisis and called for explicit efforts to improve its quality.2 Similar concerns have been raised by others who argue that globally, especially in low- and middle-income countries, what is needed to improve outcomes and save lives is not more technology but better care, including standards, systems, and social development.3

As the cancer community grapples with the challenge of how to improve cancer care, the change process in health care has been driven by two approaches that operate mostly in isolation from each other: (quality) improvement science and implementation science. Broadly, improvement science refers to systems-level work to improve the quality, safety, and value of health care, whereas implementation science refers to work to promote the systematic uptake of evidence-based interventions into practice and policy. The two fields arose from different philosophical underpinnings: Improvement science from industry, mostly automotive, takes a pragmatic approach to the reduction of poor performance in health,4 whereas implementation science from behavioral science focuses on a need to adopt new evidence into practice.5 These two disciplines fit well into two aspects of the high-quality care delivery system, as depicted in the Institute of Medicine report2 (Fig 1): implementation science through focusing on timely and appropriate uptake of evidence and improvement science through measuring performance to achieve improvement. Although the goals of the two fields seem complementary, they interact only sporadically and superficially, often at odds, and remain isolated from each other not only through their distinct methodology but also through their effect on and engagement with the health care system. As such, neither field has fully realized its potential to improve cancer care.

Fig 1.

Conceptual representation of the quality cancer care system. Adapted with permission from the Institute of Medicine.2

The objective of this editorial is to consider how the integration of these two approaches can contribute to improvement in cancer care. We argue that it is time for the two approaches to become more closely aligned so that health care providers and researchers can harness the full power of a synergistic approach that is greater than its parts.

Similar Goals, Different Terminology

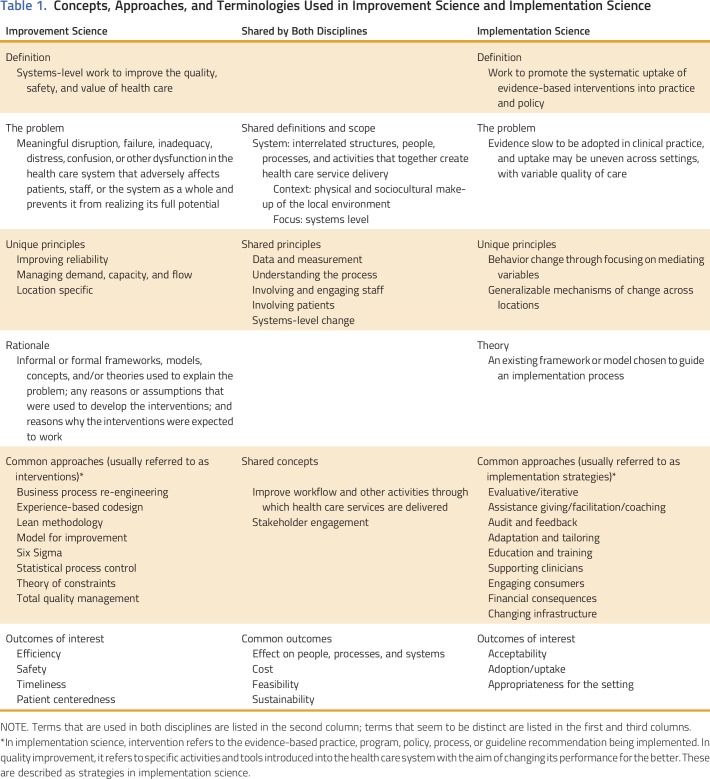

Table 1 lists some of the concepts, approaches, and terminologies used in improvement science and implementation science. Both disciplines share a common focus on a systems-level approach to improving care. Both consider similar concepts when making decisions on modifications to care delivery, including the context of the setting, the organization or system itself, the stakeholders (providers, staff, patients, and administrators), the process being examined, and health outcome enhancements for patients. However, the two fields use different terms for similar ideas (or sometimes the same term to indicate different ideas). For example, approaches to improvement are called interventions by improvement scientists and strategies by implementation scientists, who use the term intervention to describe the practice, program, or process to be implemented rather than the approach taken to implement it. Each field has separate guiding frameworks, theories, and methodologies and have expended little effort to date to harmonize them. These challenges in language and approaches have emerged in part because the two disciplines operate separately from each other, with distinct professional societies, journals, funding, and training streams. Even their geographic location within clinical and academic institutions are detached; improvement science is typically hospital based, and implementation science tends to reside within research units.

Table 1.

Concepts, Approaches, and Terminologies Used in Improvement Science and Implementation Science

Both disciplines continue to evolve, of course. Historically, in improvement science, the outcomes of interest were changes in indicators of clinical care processes or quality with more limited explorations of why or how an intervention worked. Implementation science has experienced a similar evolution and initially used changes in treatment outcomes to measure implementation success, but more recently, it has recognized that treatment outcomes are distinct from implementation outcomes.6 Both fields are now calling for, in their own settings, a clearer definition and emphasis of ideas, such as acceptability to and effect on stakeholders, adoption/uptake, appropriateness for the setting, feasibility, and sustainability.7-9 This parallel convergence of ideas is promising, but it is not enough.

Closer alignment between improvement science and implementation science may not only reduce duplication but also, more importantly, introduce synergies. Implementation science offers insights into the mechanisms of practice change and how to assess contextual factors, which supports the assessment of how these mechanisms differ according to context,10 whereas improvement science informs the development of interventions through grassroots engagement and organizational leadership and the use of rapid-cycle learning processes informed by measuring actions and behaviors.11 The combination of the two approaches ensures richness as well as expediency and maintains focus on not only reactivity, solving the problem of low quality, but also proactivity, gleaning generalizable lessons from the work to prevent future problems. The strategic alignment of the two fields would support emergent learning and refinement of theories of change on the basis of real-time discoveries. These areas of complementary expertise are just the two that we have identified so far. There are likely to be others, but at present they are hidden by the differences in language and the lack of interaction between the two fields. Bringing the fields closer together to take advantage of the complementary expertise without compromising their unique strength requires the fulfillment of key requirements outlined below.

Communication

Effective communication between the two disciplines and their external stakeholders requires common milieus (ie, journals, meetings that welcome both methodologies), shared language, and consistency and rigor of communication. Additional mapping of the terminology to clarify areas of difference and promote harmonization of common terms is needed, as is promotion of agreed publication standards.9 The publication of research results in both disciplines is critical to wider recognition of their relative contributions. Fundamentally, both fields strive to provide data that support improvement in access, quality, and outcomes of cancer care. Recent efforts of mainstream journals to encourage contributions in this area (eg, Journal of Oncology Practice section Focus on Quality) exemplify this approach.

Collaboration

Initiatives that promote collaboration in research design, conduct, and funding support and that encourage joint leadership of projects can facilitate the bringing of the fields together. Cross-fertilization across the fields could be achieved by creating structures that reward academics for partnering with cancer clinics to implement improvement projects and by allowing clinics to use and engage implementation science researchers. A learning health system, as envisioned by the Institute of Medicine, is a model where such cross-fertilization would be realized. An example of a potential benefit of such collaboration is in medical homes and accountable care organizations, which although offer opportunities to improve quality through the learning health system approach, pose significant implementation challenges.

Champions

Senior and junior faculty/professionals who are familiar with both fields, appreciate the potential of the two disciplines, and span the boundaries between these disciplines is needed. Additional research that explores how to train, support, and incentivize professionals to work across both fields is needed.

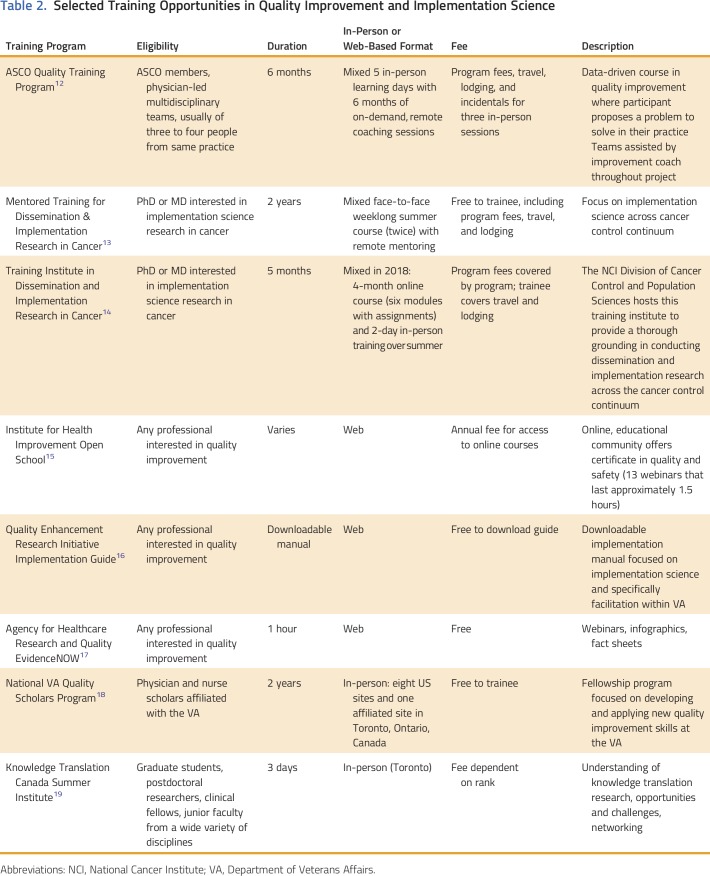

Curriculum

Both fields have a growing number of training programs (Table 2). These programs may be strengthened by greater inclusion of common content and by illustrations of unique strengths and differences between the fields.

Table 2.

Selected Training Opportunities in Quality Improvement and Implementation Science

Clarity of regulatory obligations

In contrast to implementation science, an improvement science intervention frequently is exempt from institutional review board approval. A need exists for a consistent approach to regulatory oversight that fits the needs of proposed studies, irrespective of the methodologies used. A systematic approach that uses a checklist that considers intent, methodology, benefits, risks, applicability of results, and sharing and dissemination of findings has been proposed by Ogrinc et al20 and warrants broader uptake.

In conclusion, as learning health care system approaches are more commonly adopted in cancer, closer integration between improvement science and implementation science will be necessary to achieve goals of better care. Focus on quality is not only about reducing poor quality but also about implementing evidence to improve quality. Implementation of new evidence cannot occur without consideration about how it effects quality of care. To optimize the quality of cancer care, the two fields perhaps should be seen as not only complementary but also interdependent. As cancer researchers, improvement scientists, health care providers, and potential future users of cancer services, we have an opportunity as well as a responsibility to use our scientific capital wisely. Let us not allow for silos when synergy can flourish.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported by the Mentored Training in Dissemination & Implementation Research in Cancer; National Cancer Institute grant 5R25CA171994 (principal investigator Brownson); the National Breast Cancer Foundation (to B.K.); the Department of Veterans Affairs (to L.D.); a Cancer Prevention, Control, Behavioral Sciences, and Populations Sciences Career Development Award from the National Cancer Institute (K07CA211971 to M.M.D.); a Conquer Cancer Foundation Career Development Award, Department of Veterans Affairs regional (VISN1) Career Development Award, and Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center Department of Surgery Dow-Crichlow Award (to F.R.S.); and a Veterans Administration Health Services Research and Development Career Development Award (CDA 13-025 to L.L.Z.). The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Collection and assembly of data: All authors

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Harnessing the Synergy Between Improvement Science and Implementation Science in Cancer: A Call to Action

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jop/site/ifc/journal-policies.html.

Bogda Koczwara

No relationship to disclose

Angela M. Stover

No relationship to disclose

Louise Davies

No relationship to disclose

Melinda M. Davis

No relationship to disclose

Linda Fleisher

Honoraria: Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators

Research Funding: Merck Sharp & Dohme

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators

Shoba Ramanadhan

No relationship to disclose

Florian R. Schroeck

Other Relationship: Eleven Biotherapeutics

Leah L. Zullig

Honoraria: Novartis

David A. Chambers

No relationship to disclose

Enola Proctor

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Macleod MR, Michie S, Roberts I, et al. Biomedical research: Increasing value, reducing waste. Lancet. 2014;383:101–104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62329-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IOM (Institute of Medicine) Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan R, Pramesh CS, Booth CM. Cancer patients need better care, not just more technology. Nature. 2017;549:325–328. doi: 10.1038/549325a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidoff F, Dixon-Woods M, Leviton L, et al. Demystifying theory and its use in improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24:228–238. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adesoye T, Greenberg CC, Neuman HB. Optimizing cancer care delivery through implementation science. Front Oncol. 2016;6:1. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38:65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, et al. Bridging research and practice: Models for dissemination and implementation research. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, et al. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;25:986–992. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, et al. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) statement. BMJ. 2017;356:i6795. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell SA, Chambers DA. Leveraging implementation science to improve cancer care delivery and patient outcomes. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:523–529. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.024729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plsek PE.Quality improvement methods in clinical medicine Pediatrics 103203–214.1999(suppl [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Society of Clinical Oncology Professional Development. https://www.asco.org/training-education/professional-development/quality-training-program

- 13.Washington University in St Louis What Is the MT-DIRC? http://mtdirc.org

- 14.National Cancer Institute Division of Cancer Control & Population Sciences Training Institute for Dissemination and Implementation Research in Cancer (TIDIRC) https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/IS/training-education/tidirc/index.html

- 15.Institute for Healthcare Improvement Open School. http://www.ihi.org/education/ihiopenschool/Pages/default.aspx

- 16.US Department of Veterans Affairs QUERI–Quality Enhancement Research Initiative. https://www.queri.research.va.gov/tools/implementation.cfm

- 17.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality EvidenceNOW Tools and Materials. doi: 10.1080/15360280802537332. https://www.ahrq.gov/evidencenow/tools-and-materials [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.VA Quality Scholars VA Quality Scholars: Fellowship, Scholarship, Mentorship. https://www.vaqs.org

- 19.Knowledge Translation Canada Summer Institute. https://ktcanada.org/education/summer-institute

- 20.Ogrinc G, Nelson WA, Adams SM, et al. An instrument to differentiate between clinical research and quality improvement. IRB. 2013;35:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]