Abstract

Background

We sought to characterize the perspectives of participants in Canada's phase I/II chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI) clinical trial prior to and after the disclosure of trial results.

Methods

This was a researcher-administered survey of individuals who participated in Canada's CCSVI trial (Clincialtrials.gov, NCT01864941) about their (1) motivations for participating, (2) understanding of the trial process, and (3) perspectives on the social value of the trial.

Results

A total of 63 participants completed the survey. Participants were motivated to participate by altruism (mean score = 4.56 out of 5) and a desire to access the intervention in Canada (mean score = 3.63 out of 5). Many participants expected medical benefits, such as partial disease reversal (mean score = 3.32 out of 5). Participants felt strongly that the crossover trial design promoted fairness (mean score = 4.65 out of 5). Participants' familiarity with the CCSVI controversy increased significantly after the results were revealed (p = 0.0001). Despite negative trial results, participants still felt that the trial was an appropriate use of tax dollars (mean score = 4.68 out of 5). Many (38%) upheld the belief that further CCSVI research is necessary (responses of 4 out of 5 or higher).

Conclusions

There is a strong movement in science today to ensure that research agendas reflect the perspectives of multiple stakeholders, including research participants. While previous work suggests that negative findings adversely affect trust in science, the perspectives of participants in this study demonstrate that good trial design and resilience can prevail over expected tensions.

Investments in experimental interventions for neurologic disease over recent years have led to many advances in scientific knowledge and therapeutic approaches.1–3 When new advances suggest the prospect of a cure, they naturally bring hope to patient communities that face debilitating disease. Negative findings in trials investigating potential interventions for neurodegenerative disease such as hyperbaric oxygen for multiple sclerosis (MS) in 1987 and lithium for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in 2013 are examples of ideas promoted with therapeutic promise that fell short of public hope.4,5 One of the more recent examples of such a trajectory is that of chronic cerebrospinal insufficiency (CCSVI).

The CCSVI intervention became a focus for MS when a small study suggested that an angioplasty-like procedure could reverse the symptoms of the disease.6 Despite studies that refuted the validity of this hypothesis, support for the intervention persisted in patient communities across North America.7–9 Due to immense public pressure, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research convened an expert panel to deliberate on the available evidence for CCSVI and recommended that a phase I/II interventional trial be funded.9,10 A total of 104 participants with narrowed jugular or azygos veins received the CCSVI intervention and were monitored using various cognitive and functional tests.11 This trial ultimately showed no significant difference in safety or efficacy outcomes at week 48.12

Given the simultaneous scientific controversy and public pressure to access the CCSVI intervention, this was an unprecedented time in the history of Canadian health research. We captured it as a unique opportunity to study the views and motivations of participants in the trial.

Methods

Study protocol and participants

We conducted an interviewer-administered survey over the phone with participants of Canada's CCSVI clinical trial (Clinicialtrials.gov, NCT01864941). Three of the 4 clinical sites (Vancouver, Winnipeg, and Montreal) participated and received ethics approval. Participants who had agreed to be recontacted about future research were approached in person at a trial follow-up visit or over the phone about participation in the survey. The researchers made clear that participation was independent of the main clinical trial and voluntary. Interested participants were given consent forms and were scheduled to complete two 20-minute surveys over the phone. The first survey was administered between December 7, 2016, and March 6, 2017. The second study was administered between March 7, 2017, and May 5, 2017, after the preliminary results of the CCSVI trial were sent to study participants via email from the research group (appendices e-3 and e-4, links.lww.com/CPJ/A30), reported at an international scientific conference, and featured on mainstream news and social media.

Survey design

We created survey questions based on previous literature investigating the perspectives of research participants in clinical trials.13–15 A patient representative and experts in neurology, ethics, and clinical trial design curated the survey tool (appendix e-1, links.lww.com/CPJ/A30). A total of 10 questions and 29 subquestions were used, and all responses were recorded on a 1–5 Likert scale (e.g., 1: strongly disagree, 2: disagree, 3: neither agree nor disagree, 4: agree, 5: strongly agree). The survey probed participants about their (1) motivations for participating, (2) understanding of the clinical trial process, and (3) perspectives on the social value of the CCSVI trial. We also elicited demographic data about sources of information about CCSVI, education, and annual household income. Additional demographic information was obtained from data linked with the original clinical trial.

Statistical analyses

Mean participant response on the 1–5 scale was calculated for all questions at both survey time points. Statistical differences between surveys before and after results reveal were determined by calculating the mean and SD of responses and using paired t tests. We evaluated the correlation between responses to questions in the survey by determining the Pearson R coefficient. All p values were 2-sided and were considered significant if p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were completed using GraphPad Prism 7. Results are presented in the text as mean ± SD.

Standard protocol approval, registrations, and participant consent

This study was approved by the University of British Columbia Clinical Research Ethics Board (H12-01153), University of Manitoba Behavioural Research Ethics Board (HS18301), and the Université de Montréal Research Ethics Board (2013–3212). All participants provided written informed consent. The trial identification number is NCT01864941 (Clinicialtrials.gov).

Data availability

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.

Results

Out of the 104 participants in Canada's CCSVI clinical trial, 10 participants were excluded as one trial site did not administer the survey. For the remaining 3 centers, 63 participants completed the survey before and after results reveal giving an overall response rate of 67% (figure 1). Due to time constraints, 14 participants could not complete survey 1 before preliminary results were announced on March 7, 2017. Demographic data for the cohort are summarized in the table.

Figure 1. Recruitment flow chart.

*Cutoff date for survey 1 was March 7, 2017, as this was when preliminary results of the study were announced.

Table.

Participant demographics

Overall, we found few significant differences in survey responses between survey 1 and 2. Therefore, unless otherwise noted, we report mean response values exclusively for survey 1. The full dataset for all questions at both time points can be found in appendix e-2 (links.lww.com/CPJ/A30).

Expectations and motivations

Participants were primarily motivated to participate in the trial to advance understanding or treatment of MS (4.56 ± 0.69). Desire to access the procedure in Canada was also a prominent motivation (3.63 ± 0.32). Participants expected some degree of medical benefit. Indeed, 63.3% agreed (selected either a 4 or 5 on the 1–5 scale) that they expected that the intervention would slow down their disease and 53.3% expected partial disease reversal. These results were obtained even though the trial consent form stated the goals were to investigate the safety and tolerability of the CCSVI procedure and included the following language regarding potential benefits: “There have been undocumented reports that some (we do not know how many) patients benefited from the vascular procedure. It could be the treatment benefit, if it exists, only helps symptoms rather than curing MS. The mechanism is unknown.”

Few participants expected that the intervention would provide a cure (4.8%) or have no effect on their disease course (15%) (figure 2A). There was variability in whether or not participants' expectations of medical benefit from the trial were met (3.32 ± 1.4) (figure 2B). The data demonstrate a positive correlation between reported motivations to participate in the trial for the advancement of knowledge about MS (R = 0.289, p = 0.02) and expectations of medical benefit.

Figure 2. Expectations of medical benefits among participant's in Canada's chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI) trial.

(A) Degree of medical benefit expected by participants. (B) Degree to which expectations of medical benefit were met. (C) Familiarity with the controversy surrounding CCSVI before and after results reveal (left bars, n = 63) and whether participation in the study was discouraged among participants who were aware of the controversies before (orange bar on right, n = 44) and after (blue bar on left, n = 54) the results were revealed.

Understanding the clinical trial process

Participants reported that the trial was explained to them thoroughly (4.70 ± 0.50) and that they understood the trial process (4.60 ± 0.55). Participants also agreed that the use of 2 procedures in the crossover trial were necessary to generate credible results (4.57 ± 0.67), an appropriate trade-off for credible science (4.59 ± 0.73), and promoted fairness in the trial (4.65 ± 0.63). There was an increase (p = 0.0001) in participants' familiarity with the controversies surrounding the CCSVI procedure before (2.65 ± 1.47) and after the results reveal (3.62 ± 1.41) (figure 2C). Of those familiar with the controversies, the decision to partake or continue to participate in the trial was minimally discouraged by the surrounding controversies (1.41 ± 0.87, n = 44) (figure 2C).

Perspectives on the social value of the CCSVI trial

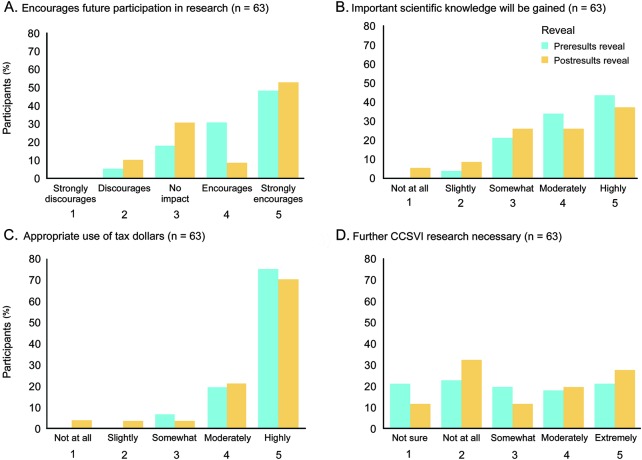

Participants largely felt encouraged (4.21 ± 0.90) to participate in future research studies given their experience in the CCSVI clinical trial (figure 3). The degree to which participants felt that important scientific knowledge would be gained as a result of the trial decreased (p = 0.025) when comparing perspectives before (4.16 ± 0.87) and after (3.81 ± 1.16) the results reveal. Participants felt strongly that the CCSVI trial was an appropriate use of taxpayer money (4.68 ± 0.59). Indeed, 75% responded that it was “absolutely appropriate” (5 out of 5 on scale). The cohort was roughly evenly divided about the need for further CCSVI research as 57% responded that further research was needed to some extent (2.95 ± 1.44) (figure 3).

Figure 3. Perspectives of participants about the social value of Canada's cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI) clinical trial.

Participant perspective about whether (A) their experience in the CCSVI clinical trial encourages them to participate in future research; (B) important scientific knowledge will be gained from the study; (C) the study was an appropriate use of taxpayer dollars; (D) further CCSVI research is necessary.

Discussion

We sought to characterize the perspectives of participants about their involvement in Canada's CCSVI clinical trial. Prior studies have reported on the perspectives of individuals with MS who obtained the intervention abroad through unregulated routes such as medical tourism.16 This study examines perspectives of those who participated in a regulated clinical trial, both prior to and after the disclosure of negative results. The most prominent differences between the prereveal and postreveal of the results were an unsurprising increase in familiarity with the controversy given the media coverage and a decrease in how strongly participants felt scientific knowledge would be gained from the CCSVI trial. Despite negative results, participants believed that initial investment in the CCSVI trial was justified.

Have we learned lessons from this episode in neurologic science? We suggest that there are indeed a number of important take-home messages about motivation to participate, the impetus for access, disclosure, and resilience.

Motivation to participate

Like other studies that have shown that altruism is a dominant motivator for clinical trial enrollment, participants in this study were similarly motivated by aspirational benefits, such as advancing the understanding or treatment of MS.17–22 Many also expressed that they were motivated by access to the procedure in Canada, and expected some degree of direct medical benefit. Therapeutic misconception, or the conflation of goals of research (to produce knowledge) with those of medical care (to provide treatment), is hardly unusual in clinical research.23–29 It is important to note that therapeutic misconception may undermine informed consent if participants' expectations do not align with the goals of clinical research. Expectations for direct medical benefit in this early-phase trial may have been heightened by highly visible claims in the public sphere about the efficacy of the CCSVI intervention and its availability out of country even while more skeptical discussions were ongoing in the professional community.9,16,30,31

The impetus for access

The impetus for access to the CCSVI procedure was particularly pronounced in the CCSVI context, and driven more by pressure from patient communities than by scientific evidence.32 Public demand to access developing biotechnologies is evident through a surge in medical tourism and new initiatives to promote compassionate access platforms though Right to Try legislation.33 As seen in the present study, many participants were motivated to enroll in the CCSVI trial because they believed it was the only opportunity to receive the intervention locally. Contemporary reforms in clinical trial design reflect public priorities to promote access to experimental interventions, and include crossover studies, adaptive clinical trials, and combined phase designs, among others.34,35 These alternative routes of regulated access may reduce the number of adverse events experienced by patients who choose to go abroad for interventions—such as fatalities in the case of CCSVI procedure abroad—while promoting the utilitarian goal of knowledge generation by way of clinical research.36,37

The crossover trial design utilized in the CCSVI clinical trial, first described by Chassan38 and Grizzle,39 enabled all participants to receive the experimental intervention rather than an inert intervention as in placebo-controlled trials. The downside of such a design, however, is that it exposes participants to increased risk, requires lengthier and potentially more burdensome research participation, and increases research costs. Many studies have investigated participant understanding and perspectives about traditional randomized clinical trials.40,41 Here, in the study of participant perspectives about the use of a crossover trial design, we find widespread acceptance among participants of the associated trade-offs. In light of this finding, we suggest that crossover trials may be a powerful approach to trial design, especially where there is an immense desire for access to a procedure.

Disclosure of scientific controversy

While the consent documents for the CCSVI trial articulated the existence of studies that contradicted the CCSVI hypothesis, the results suggest that many participants were unfamiliar with the controversy. Clearly, one of the challenges of communicating science, especially in the context of clinical trials, is that emotive forces may bias participants to expect certain outcomes.12 Responsible communication is not merely about filling deficits in knowledge, but also assuring that dialogue about interventions is balanced.42 The media remains a prominent source of health information for the public and has a profound effect on the discourse surrounding emerging biotechnologies.42 In other fields of nonpharmaceutical interventions for MS such as stem research, recent evidence suggests the presence of more socially responsible reporting by the media.43 Pentz et al.13 conducted a study on the understanding of participants before and after the informed consent form for a phase I cancer clinical trial with substantial media attention, similar to CCSVI, and report that only 33% correctly understood the study goals. In addition, they report that the consent process in a high-profile clinical trial only increased patient comprehension of purpose by 13%. Howe44 and Cohen et al.45 stipulate that even when participants are aware of a low probability of benefit in phase I trials, the possibility of improvement still allows for the preservation of hope. Given these challenges, future research may focus on how the disclosure of controversy during the consent process may influence participants' involvement in clinical research.

Resilience

We interpret participants' continued interest in participating in future research after receiving both interventions and negative trial results as resilience and an enduring support for the scientific process. Participants' involvement in the trial was not discouraged by any knowledge of the controversies surrounding CCSVI (figure 2C). Even after the results of the trial were revealed, participants felt strongly that the financial investment in the trial was an appropriate use of tax dollars and that important knowledge had been gained from the trial. These perspectives diverge from those of individuals who did not pursue CCSVI interventions, and who instead felt that funds could have been invested in other areas of MS research with more scientific rigor, such as stem cell research.46 Participants did not have a general consensus on whether further CCSVI research is needed, and in fact some felt strongly that further work is necessary. This divergence among patients speaks to both the frustration and continuing hope in the community.16,46

A number of limitations of the present study may have had an effect on the results. First, initial survey responses were collected only after participants had already received both surgeries. Surveying individuals prior to receiving any intervention might have provided a more accurate indication of motivation to enroll in the CCSVI trial. Second, the trial results were announced earlier than originally anticipated, limiting the number of participants who could be surveyed. Finally, while researcher administration of the survey allowed for opportunities to answer participants' questions and provide clarity, it may have also introduced a social desirability bias.

Increasingly, efforts have been made to encourage the engagement of multiple stakeholders, including research participants, in the creation and governance of science.8 CCSVI was not a triumph for this model. It is however a moment in the history of neurology that highlights how civic engagement can polarize expert and public opinions. The results of this study may be generalizable to future examples of early-phase research in neurologic science that receive considerable interest from the public. Past work would suggest that diverging perspectives can produce an adverse effect on trust in science and governing bodies.16 In the present context, good trial design and the resilience of the MS community prevailed over associated tensions.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the research participants for their time completing the survey; the clinical trial offices at the University of British Columbia, University of Manitoba, Université Laval, and McGill for their support and assistance with the logistical aspects of data collection, reviewing the content of the questionnaire, and providing feedback; Laura Harvey and Peggy Law for assistance with data collection; a patient with MS for feedback on study design; and Caroline Taylor for contributions to statistical analyses. J.I. is Canada Research Chair in Neuroethics.

Footnotes

Podcast: NPub.org/NCP/podcast8-3b

Author contributions

Shelly Benjaminy: study design, implementation, data analysis and synthesis, and writing of manuscript. Cody Lo: implementation, data analysis and synthesis, and writing of manuscript. Judy Illes: study design, implementation, data analysis and synthesis, and writing of manuscript. Anthony Traboulsee: study design, implementation, data analysis and synthesis, and writing of manuscript.

Study funding

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research, and the Multiple Sclerosis Societies of Canada, British Columbia, Manitoba, and Quebec.

Disclosure

S. Benjaminy receives research support from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, University of British Columbia, Stem Cell Network Canada, and Multiple Sclerosis Society of Vernon. C. Lo reports no disclosures. J. Illes serves as Vice Chair of the CIHR Standing Committee on Ethics and of the Internal Advisory Board of INMHA; serves as a Trustee of the UBC Peter Wall Institute of Advanced Studies and an elected member of the Research Leaders Forum of the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research; serves on the editorial boards of Canadian Journal of Bioethics, Journal of Law and Biosciences, Frontiers in Ethics and Genetics, American Journal of Bioethics, and American Journal of Bioethics-Neuroscience; receives publishing royalties for Neuroethics: Defining the Issues in Theory, Practice and Policy (Oxford University Press, 2006), Handbook of Neuroethics (Oxford University Press, 2011), Addiction Neuroethics (Elsevier Press, 2012), The Use and Overuse of Antipsychotics in Children and Youth (Elsevier, 2015), and Neuroethics: Anticipating the Future, (Oxford University Press, 2017), and Series: Developments in Neuroethics and Biomedicine (Elsevier Press, 2017–2020, in preparation); and receives research support from Technical Safety BC, CIHR, Networks of Centres of Excellence NeuroDevNet/Kids Brain Health Network (her husband also receives support from this network), University of Toronto, James Fund, and Dana Foundation. A. Traboulsee serves on scientific advisory boards for Sanofi Genzyme, MS Society of Canada, Canadian Institute for Health Research, and CADTH; has received funding for travel or speaker honoraria from Sanofi Genzyme, Biogen, Teva, Novartis, Roche, and MS Society of Canada; serves as a consultant for Biogen, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Serono, and Teva Innovation; and receives research support from Roche, Chugai, Novartis, Biogen, Sanofi Genzyme, and Canadian Institute for Health Research. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Oh J, Calabresi PA. Emerging injectable therapies for multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:1115–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ziemssen T, Derfuss T, Stefano N, et al. Optimizing treatment success in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2016;263:1053–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luessi F, Siffrin V, Zipp F. Neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis: novel treatment strategies. Expert Rev Neurother 2012;12:1061–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UKMND-LiCALS Study Group. Lithium in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (LiCALS): a phase 3 multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:339–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes MP, Bates D, Cartlidge NE, French JM, Shaw DA. Hyperbaric oxygen and multiple sclerosis: final results of a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1987;50:1402–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zamboni P, Galeotti R, Menegatti E, et al. A prospective open-label study of endovascular treatment of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg 2009;50:1348–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doepp F, Paul F, Valdueza JM, Schmierer K, Schreiber SJ. No cerebrocervical venous congestion in patients with multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2010;68:173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benjaminy S, Traboulsee A. At the crossroads of civic engagement. In: Neuroethics: Anticipating the Future. New York: Oxford University Press; 2017:264. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pullman D, Zarzeczny A, Picard A. Media, politics and science policy: MS and evidence from the CCSVI Trenches'. BMC Med Ethics 2013;14:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Highlights from the June 28, 2011 CIHR scientific expert working group meeting [online]. Available at: cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/43952.html. Accessed October 25, 2017.

- 11.ClinicalTrials.gov. Interventional clinical trial for CCSVI in multiple sclerosis patients [online]. Available at: clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01864941?term=CCSVI+traboulsee&rank=1. Accessed August 29, 2017.

- 12.Machan L, Traboulsee A, Siskin G, et al. Safety and efficacy of jugular and azygos venoplasty in multiple sclerosis: a randomized, double blind, sham-controlled phase II trial: week 48 results. Presented at the Society of Interventional Radiology conference; March 8, 2017; Washington, DC.

- 13.Pentz RD, Flamm AL, Sugarman J, et al. Study of the media's potential influence on prospective research participants' understanding of and motivations for participation in a high-profile phase I trial. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:3785–3791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox AC, Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA. Communication and informed consent in phase 1 trials: a review of the literature. Support Care Cancer 2006;14:303–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mills EJ, Seely D, Rachlis B, et al. Barriers to participation in clinical trials of cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review of patient-reported factors. Lancet Oncol 2006;7:141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snyder J, Adams K, Crooks VA, Whitehurst D, Vallee J. “I knew what was going to happen if I did nothing and so I was going to do something”: faith, hope, and trust in the decisions of Canadians with multiple sclerosis to seek unproven interventions abroad. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Penman DT, Holland JC, Bahna GF, et al. Informed consent for investigational chemotherapy: patients' and physicians' perceptions. J Clin Oncol 1984;2:849–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodenhuis S, Van Den Heuvel WJA, Annyas AA, Koops HS, Sleijfer DT, Mulder NH. Patient motivation and informed consent in phase I study of an anticancer agent. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1984;20:457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kodish E, Stocking C, Ratain MJ, Kohrman A, Siegler M. Ethical issues in phase I oncology research: a comparison of investigators and institutional review board chairpersons. J Clin Oncol 1992;10:1810–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daugherty C, Ratain MJ, Grochowski E, et al. Perceptions of cancer patients and their physicians involved in phase I trials. J Clin Oncol 1995;13:1062–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Itoh K, Sasaki Y, Fuji H, et al. Patients in phase I trials of anti-cancer in Japan: motivation, comprehension and expectations. Br J Cancer 1997;76:107–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoder LH, O'Rourke TJ, Ethyre A, Spears DT. Expectations and experiences of patients with cancer participating in phase I clinical trials. Oncol Nurs Forum 1997;24:891–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Appelbaum PS, Roth LH, Lidz C. The therapeutic misconception: informed consent in psychiatric research. Int J L Psychiatry 1982;5:319–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joffe S, Cook EF, Cleary PD, Clark JW, Weeks JC. Quality of informed consent in cancer clinical trials: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet 2001;358:1772–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ballard HO, Shook LA, Iocono J, Bernard P, Hayes D. Parents' understanding and recall of informed consent information for neonatal research. IRB 2010;33:12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benjaminy S, MacDonald I, Bubela T. “Is a cure in my sight?” Multi-stakeholder perspectives on phase I choroideremia gene transfer clinical trials. Genet Med 2014;16:379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chappuy H, Baruchel A, Leverger G, et al. Parental comprehension and satisfaction in informed consent in paediatric clinical trials: a prospective study on childhood leukaemia. Arch Dis Child 2010;95:800–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hazen RA, Drotar D, Kodish E. The role of the consent document in informed consent for pediatric leukemia trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2007;28:401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misra S, Socherman R, Hauser P, Ganzini L. Appreciation of research information in patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2008;10:635–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazanderani F, O'Neill B, Powell J. “People power” or “pester power”? YouTube as a forum for the generation of evidence and patient advocacy. Patient Educ Couns 2013;93:420–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghahari S, Forwell SJ. Social media representation of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency intervention for multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care 2016;18:49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chafe R, Born KB, Slutsky AS, Laupacis A. The rise of people power. Nature 2011;472: 410–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Servick K. “Right to Try” laws bypass FDA for last-ditch treatments. Science 2014;344:1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: adaptive design clinical trials for drugs and biologics. Available at: fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/ucm201790.pdf. Accessed November 16, 2017.

- 35.Stallard N. A confirmatory seamless phase II/III clinical trial design incorporating short-term endpoint information. Stat Med 2002;29:959–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.CBC News. 2nd Canadian dies after MS surgery [online]. Available at: cbc.ca/news/health/2nd-canadian-dies-after-ms-surgery-1.1031686. Accessed October 26, 2017.

- 37.Burton JM, Alikhani K, Goyal M, et al. Complications in MS patients after CCSVI procedures abroad (Calgary, AB). Can J Neurol Sci 2011;38:741–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chassan JB. On the analysis of simple crossovers with unequal numbers of replicates. Biometrics 1964;20:206–208. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grizzle JE. The two-period change-over design and its use in clinical trials. Biometrics 1965;21:467–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Featherstone K, Donovan JL. Random allocation or allocation at random? Patients' perspectives of participation in a randomized controlled trial. Br Med J 1998;317:1177–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edwards SJ, Lilford RJ, Hewison J. The ethics of randomised controlled trials from the perspectives of patients, the public, and healthcare professionals. BMJ 1998;317:1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bubela T, Nisbet MC, Borchelt R, et al. Science communication reconsidered. Nat Biotechnol 2009;27:514–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benjaminy S, Lo C, Illes J. Social responsibility in stem cell research: is the news all bad? Stem Cel Rev 2016;12:269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Howe HG. “Sacred” research practices we may want to change. J Clin Ethics 1999;10:9–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen L, deMoor C, Amato R. The association between treatment: specific optimism and depressive symptomatology in patients enrolled in a phase I cancer clinical trial. Cancer 2001;91:1949–1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benjaminy S, Illes J, Schepmyer A, Traboulsee A. After the hype: stem cell research in the post-CCSVI era. Presented at Till and McCulloch Meeting; October 25, 2016; Whistler, Canada.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.