Abstract

Women with Asherman syndrome (AS) have intrauterine adhesions obliterating the uterine cavity. Hysteroscopic March classification describes the adhesions which graded in terms of severity. This study has been designed to assess the prevalence and association between of clinical presentations, potential causes, and hysteroscopic March classification of AS among infertile women with endometrial thickness.

A retrospective descriptive study was carried out that included 41 women diagnosed with AS. All of the patients underwent evaluation and detailed history. All cases classified according to March classification of AS were recorded. Patients were divided into 2 groups based on measurement of endometrial thickness. Group A consisted of 26 patients with endometrial thickness ≤5 mm, and group B included 15 patients with endometrial thickness >5 mm.

The prevalence of AS was 4.6%. Hypomenorrhea was identified in about 46.3%, and secondary infertility 70.7%. History of induced abortion, curettage, and postpartum hemorrhage were reported among 56.1%, 51.2%, and 31.7%, respectively. AS cases were classified as minimal in 34.1%, moderate 41.5%, and severe among 24.4% as per March classification. Amenorrhea was reported by 23.1% of women in group A, compared to 0% in group B (P = .002). Ten of 26 patients (38.5%) from group A had a severe form of March classification, compared with 0 of 15 patients (0%) in group B. This was statistically significant (P < .001).

The thin endometrium associated with amenorrhea and severe form of March classification among patients with AS.

Keywords: Asherman syndrome, clinical features, infertile, March classification

1. Introduction

Asherman syndrome (AS) was first described by Joseph G. Asherman but the first case of intrauterine adhesion was published in 1894 by Heinrich Fritsch.[1] It is defined as intrauterine adhesions obliterating the uterine cavity partially or completely after trauma to the basalis layer of the endometrium.[2]

Patients with AS may present with menstrual period disturbance like amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, and oligomenorrhea due to a marked reduction in myometrial vascular flow.[3] Such changes may have an effect on implantation and may lead to infertility since the hypotrophic endometrium becomes unreceptive to an embryo. Obstetrical complications and recurrent miscarriages have been reported with AS.[4]

The etiology of AS is not clear; however, an event that causes damage to the endometrium can lead to the development of adhesions. AS most frequently occur after repeated curettage, postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), and elective abortion. Additionally, AS may occur after a simple operation on the uterus like a cesarean section (CS) and myomectomy.[5–7] Presently, AS is known to be associated with nontraumatic factors, for example, puerperal sepsis,[8] infections such as tuberculous endometritis, and even after a normal delivery.[9]

Direct visualization of the uterus via hysteroscopy is the most reliable method for diagnosis. Hysteroscopic adhesiolysis is the treatment of choice for the management of intrauterine adhesions.[10]

The ideal classification system should include a comprehensive description of the adhesions which should be graded in terms of severity. Various classification systems were developed to describe this syndrome. March et al introduced for the first time a hysteroscopic classification of AS.[10] This classification is still used for its simplicity; however, it remains inadequate for an indication for the prognosis of the disease.

This retrospective study has been designed to assess the prevalence of clinical presentations, potential causes, and hysteroscopic March classification of AS among infertile women and association with a thin endometrium.

2. Methods

An analytical retrospective descriptive study was carried out; it included all infertile women who attended the Reproductive Endocrine and Infertility Medicine Department at Women's Specialized Hospital, King Fahad Medical City, in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, from December 2008 to December 2016. All patients with a history of infertility and diagnosed with intrauterine adhesions by hysteroscopy was included in the review. Institutional review board approval was granted for the study.

All of the patients underwent evaluations, including a detailed history, age, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), types and duration of infertility, past menstrual cycle pattern, and past obstetrical history. Patient data extracted included midluteal-phase assay of reproductive hormones like follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, prolactin, progesterone, estradiol, and testosterone, in addition to the results of the hysterosalpingography which was performed.

Furthermore, the potential causes of AS, history of curettage, miscarriage, PPH, hysteroscopy, endometritis, and any uterine surgery like myomectomy and CS were also extracted and recorded.

All cases were diagnosed by hysteroscopy and classified according to March classification of AS (mild if filmy adhesion occupying less than one-quarter of uterine cavity and ostial areas and upper fundus minimally involved or clear; moderate if one-fourth to three-fourth of cavity involved and ostial areas and upper fundus partially involved and no agglutination of uterine walls; or severe if more than three-fourth of cavity involved and occlusion of both ostial area and upper fundus and agglutination of uterine walls).[10]

Transvaginal USG was done to measure the endometrial thickness in the midsagittal plane at the midcycle of the menstrual period, and if the patient has amenorrhea, we did the time when she presents in our clinic. Measurements were made from the outer edge of the endometrial-myometrial interface to the outer edge in the widest part of the endometrium. Patients were divided into 2 groups based on measurement of endometrial thickness in the midsagittal plane at the midcycle of the menstrual period. Group A consisted of 26 patients with an endometrial thickness ≤5 mm, and group B included 15 patients with an endometrial thickness >5 mm.

We excluded data for women who had a polycystic ovarian disease; tubal factor causes infertility, chromosomal anomaly, lactating or pregnant women, smoking, drinking alcohol, or abusing drugs, thyroids diseases, and hyperprolactinemia.

All categorical variables age group, Marsh classifications, curettage, PPH and previous CS were presented as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables height, weight, and BMI were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). All data were entered and analyzed through statistical package SPSS version 22.

3. Results

During the 8 years of the study from December 2008 to December 2016, around 902 couples visited the Assisted Reproductive Technology clinics. About 41 women were confirmed to have uterine adhesions by hysteroscopy, with a prevalence of 4.6%.

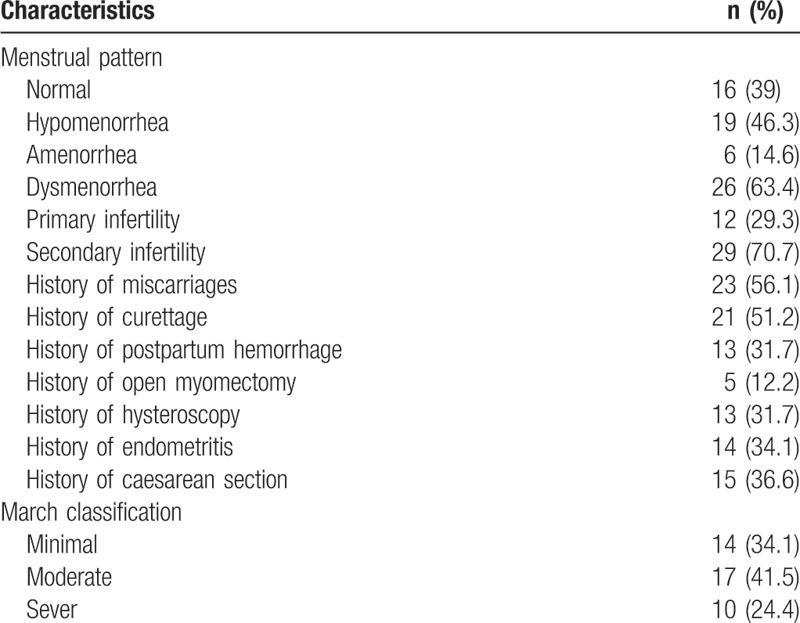

The data for 41 women (Table 1) who attended the Assisted Reproductive Technology clinics during the 8 years of the study from December 2008 to December 2016 were extracted. Their age ranged between 21 and 39 years with a mean ± SD of 32.24 ± 4.61 years. Their BMI ranged between 23.4 and 38.1 kg/m2 with a mean ± SD of 29.07 ± 3.60 kg/m2. Their duration of infertility ranged between 2 and 23.4 years with a median ± SD of 6.12 ± 3.87. Patients’ demographics were demonstrated in Table 1. Regarding the menstrual pattern, the majority of cases had hypomenorrhea (46.3%), amenorrhea in 14.6%, and the normal menstrual pattern was reported among 39%. Dysmenorrhea was reported among 63.4%. Most patients had secondary infertility (70.7%), whereas primary infertility was seen among the remaining women (29.3%). The commonest etiological factor was a history of induced abortion, curettage, and PPH (56.1%, 51.2%, and 31.7%, respectively). Open myomectomy, hysteroscopy, and endometritis were reported among 12.2%, 31.7%, and 34.1% of the participants, respectively. About 36.6% of all cases had a previous CS. According to hysteroscopic March classification, AS cases were classified as minimal in 34.1%, moderate 41.5%, and severe among 24.4%.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients (n = 41).

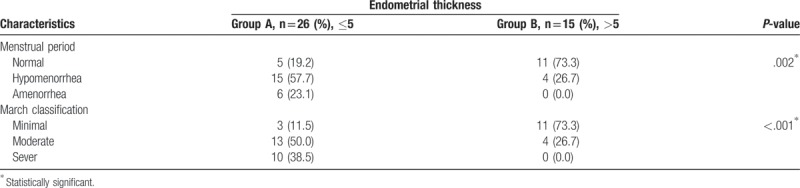

From Table 2, it is evident that among the studied factors that could be associated with endometrial thickness, menstrual period pattern, and March classification were significantly associated with endometrial thickness. Amenorrhea was reported by 23.1% of women in group A, compared to 0% in group B (P = .002). Ten of 26 patients (38.5%) from group A had a severe form of March classification, compared with 0 of 15 patients (0%) in group B. This was statistically significant (P < .001).

Table 2.

Association between menstrual period characteristics, March classification, and endometrial thickness.

4. Discussion

The AS has always been a disease difficult to diagnose and the true incidence of intrauterine adhesions remains unknown since the majority of the patients are asymptomatic. The prevalence of AS in this study was found to be 4.6% among the infertile population. This is comparable to previous reports of 2% to 5%,[11–13] and reports of 6.3% of AS among the infertile population in Nigeria.[6] The prevalence varies between 0.3% as an incidental finding among asymptomatic women to 21.5% in women with a history of postpartum curettage.[14] The availability of modern advanced imaging and hysteroscopy and the recognition of the condition caused an increase in the diagnosis of AS.

The most common symptom in patients with AS is menstrual abnormalities. Schenker and Margalioth reviewed 2981 patients with AS; 1102 (37%) had amenorrhea, and 924 (31%) had hypomenorrhea.[14] In our study, the most common menstrual abnormalities were hypomenorrhea in about 46.3% and amenorrhea in 14.6%. The normal menstrual pattern in our study was 39%, in which is much higher than previous reports of 5%.[11] Patients undergoing repeat curettage for incomplete abortion have an increased incidence of AS, as high as 39%.[15–18] A review of 1856 women with AS demonstrated that 67% had undergone curettage because of induced or spontaneous abortion and 22% had curettage for PPH.[14] In the present study, induced abortion and PPH were reported among 56.1% and 31.7% of them, respectively.

The risk of AS is lower when there is trauma to a nonpregnant uterus, rates of 1.3% after abdominal myomectomy has been reported.[14] The rate of AS among our subfertile women was much more (12.2%). About 36.6% of all cases had a previous CS.[19] The contribution of infection to the development of AS remains controversial and was found among 34.1%.

According to March classification,[10] cases of AS in the present study were classified as minimal (34.1%), moderate (41.5%), and severe (24.4%). Outcome and prognosis depend mainly on the degree of intrauterine adhesions.

Endometrial thickness is considered as a reflection of the degree of endometrial proliferation in the absence of intrauterine pathology. In this study, amenorrhea and severe form of March classification were observed with endometrial thickness <5 mm group.

Among the limitations of our study is the relatively small sample size as it was limited to Women's Specialized Hospital. Therefore, we recommended that provision of information, education, and counseling about this disease among infertile women. This information might aid physicians in guiding their patients and taking optimal clinical decisions together.

5. Conclusion

The thin endometrium associated with amenorrhea and severe form of March classification among patients with AS.

Author contributions

SB and AB: concept/design, data analysis/interpretation, drafting article, critical revision of article and approval of article; DA: critical revision of article and approval of article.

Conceptualization: Saeed Baradwan, Afnan Baradwan, Dania Al-Jaroudi.

Data curation: Saeed Baradwan, Afnan Baradwan.

Formal analysis: Saeed Baradwan, Afnan Baradwan.

Funding acquisition: Saeed Baradwan.

Investigation: Saeed Baradwan, Afnan Baradwan.

Methodology: Saeed Baradwan, Afnan Baradwan.

Project administration: Saeed Baradwan.

Resources: Saeed Baradwan.

Software: Saeed Baradwan.

Supervision: Saeed Baradwan, Dania Al-Jaroudi.

Validation: Saeed Baradwan, Dania Al-Jaroudi.

Visualization: Saeed Baradwan, Dania Al-Jaroudi.

Writing - original draft: Saeed Baradwan, Afnan Baradwan, Dania Al-Jaroudi.

Writing - review & editing: Saeed Baradwan, Afnan Baradwan, Dania Al-Jaroudi.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AS = Asherman syndrome, BMI = body mass index, CS = caesarean section, PPH = postpartum hemorrhage, SD = standard deviation.

The data used during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The data used for the study did not include any personal identifiers. The study was ethically approved by King Fahad Medical City Research Committee in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Asherman JG. Traumatic intra-uterine adhesions. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp 1950;57:892–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].March CM. Intrauterine adhesions. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 1995;22:491–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Polishuk W, Kohane S. Intrauterine adhesions: diagnosis and therapy. Obstet Gynecol Digest 1966;8:41. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Forssman L. Posttraumatic intrauterine synaechae and pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1965;26:710–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Valle RF, Sciarra JJ. Intrauterine adhesions: hysteroscopic diagnosis, classification, treatment, and reproductive outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1988;158:1459–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Orhue AA, Aziken ME, Igbefoh JO. A comparison of two adjunctive treatments for intrauterine adhesions following lysis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2003;82:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Schenker JG. Etiology of and therapeutic approach to synechia uteri. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1996;65:109–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Polishuk WZ, Anteby SO, Weinstein D. Puerperal endometritis and intrauterine adhesions. Int Surg 1975;60:418–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zondek R, Rozin S. Filling defect in the hysterogram simulating intrauterine synechae which disappear after denervation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1964;88:123–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].March C, Israel R. Intrauterine adhesions secondary to elective abortion. Hysteroscopic diagnosis and management. Obstet Gynecol 1976;48:422–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Otubu JAM, Olarewoju RS. Hysteroscopy in infertile Nigerian women. Afr J Med Sci 1989;18:117–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dicker D, Ashekenazi T, Deker A, et al. The value of hysteroscopic evaluation in patients with pre-clinical in vitro fertilisation abortion. Hum Reprod 1996;11:730–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Katz Z, Bon Arie A, Lurie S, et al. Reproductive outcome following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis in Asherman's syndrome. Int J Fertil Menopausal Stud 1996;41:462–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Schenker JG, Margalioth EJ. Intrauterine adhesions: an updated appraisal. Fertil Steril 1982;37:593–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dmowski WP, Greenblatt R. Asherman's syndrome and risk of placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol 1969;34:288–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kodaman PH, Arici A. Intra-uterine adhesions and fertility outcome: how to optimize success? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2007;19:207–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rabau E, David A. Intrauterine adhesions: etiology, prevention, and treatment. Obstet Gynecol 1963;22:626–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Toaff R, Ballas S. Traumatic hypomenorrhea-amenorrhea (Asherman's syndrome). Fertil Steril 1978;30:379–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ozumba BC, Ezegorui H. Intrauterine adhesions in an African population. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2002;77:37–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]