Abstract

Alternative approaches in Medicaid are proliferating under the Trump administration. Using a novel telephone survey, we assessed views on health savings accounts, work requirements, and Medicaid expansion. Our sample consisted of 2,739 low-income nonelderly adults in three Midwestern states: Ohio, which expanded eligibility for traditional Medicaid; Indiana, which expanded Medicaid using health savings accounts called POWER accounts; and Kansas, which has not expanded Medicaid. We found that coverage rates in 2017 were significantly higher in the two expansion states than in Kansas. However, cost-related barriers were more common in Indiana than in Ohio. Among Medicaid beneficiaries eligible for Indiana’s waiver program, 39 percent had not heard of POWER accounts, and only 36 percent were making required payments, which means that nearly two-thirds were potentially subject to loss of benefits or coverage. In Kansas, 77 percent of respondents supported expanding Medicaid. With regard to work requirements, 49 percent of potential Medicaid enrollees in Kansas were already employed, 34 percent were disabled, and only 11 percent were not working but would be more likely to look for a job if required by Medicaid. These findings suggest that current Medicaid innovations may lead to unintended consequences for coverage and access.

The expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has been associated with significant improvements in coverage, access to health care, and quality of care.1–6 But much of the debate at the state level since the 2016 election has shifted away from whether to expand Medicaid to what alternative approaches to take within the program. This article explores several new approaches (implemented or proposed) in Medicaid, using a novel survey of three Midwestern states.

The administration of President Donald Trump has prioritized increased flexibility for state Medicaid programs. This builds on section 1115 waivers approved during the administration of President Barack Obama, including Arkansas’s use of private coverage expansion (the “private option”) and Indiana’s consumer-oriented expansion featuring health savings accounts.7 Most recently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) approved proposals from Kentucky, Arkansas, and Indiana for the first-ever work requirements in Medicaid, and other states such as Ohio have expressed interest in following suit.8

While the private option has been well studied,2,9,10 less is known about the effects of Indiana’s expansion. The Healthy Indiana Plan (HIP) was implemented under the leadership of Vice President Mike Pence and CMS administrator Seema Verma (then both Indiana state officials). Featuring premiums, health savings accounts (called Personal Wellness and Responsibility [POWER] accounts), and a lockout period for failure to make required payments, the plan’s focus on consumer-oriented provisions has been cited by Trump administration officials as a potential exemplar for other states.11,12

Preliminary evaluations of the Healthy Indiana Plan have been mixed, with one contracted evaluation concluding that the waiver did not result in significant disenrollment in Indiana or act as a barrier to care,13 though independent assessments have criticized that evaluation as misleading.14 In contrast, another analysis of the same data found that more than half of enrollees lost some benefits because they failed to contribute to their POWER accounts,14 and qualitative interviews suggested that some enrollees did not understand the accounts.7 Recently, CMS announced it was scaling back its own evaluation plans,15 which makes the need for ongoing independent assessments even more compelling.

Meanwhile, the potential implications of work requirements in Medicaid are of significant interest to policy makers.16 Previous analyses indicate that most Medicaid beneficiaries are disabled or already working.16,17 However, to our knowledge, no studies have explored how many potential enrollees would change their employment behavior (or which demographic groups might be most likely to do so) in response to a work requirement.

This study presents survey data collected in late 2017 from low-income adults in three Midwestern states with different Medicaid policies: Indiana, which expanded coverage in 2015 via a section 1115 waiver; Ohio, which expanded Medicaid without a waiver in 2014; and Kansas, which has not expanded Medicaid (the governor vetoed an expansion bill in early 2017).18 In Kansas, debate over expanding Medicaid continues, and the state is considering imposing work requirements for both the expansion and traditional Medicaid populations.

The objectives of our study were to assess differences in coverage, access, and heath care satisfaction among low-income adults in these states; examine low-income adults’ experiences with some of the unique features of the Healthy Indiana Plan; and explore attitudes about expansion and the potential effects of Medicaid work requirements in Kansas.

Study Data And Methods

KEY STATE POLICIES

Medicaid policies in our three study states are shown in exhibit 1. Ohio had a traditional Medicaid expansion without premiums and with minimal cost sharing. Kansas has not expanded Medicaid under the ACA. This means that nondisabled childless adults in Kansas cannot qualify for Medicaid, and among other adults, only very poor parents (those with incomes at or below 38 percent of the federal poverty level) and disabled adults with incomes at or below 75 percent of poverty are eligible for Medicaid.

EXHIBIT 1.

Features of Medicaid programs in Indiana, Ohio, and Kansas, December 2017

| Indiana |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIP 2.0 Basic | HIP 2.0 Plus | Ohio | Kansas | |

| PROGRAM FEATURES | ||||

|

| ||||

| Adult eligibility criteria | Family income ≤138% of FPL | Family income ≤138% of FPL | Parents with family incomes ≤38% FPL; disabled adults with family incomes ≤75% of FPL | |

| Premium/required contribution | 2% of income, or $1 per month for those with incomes 0–5% of FPL | None | None | |

| Copayments | Graduated payments for nonemergency use of ED: $8 for first visit, $25 for any subsequent visit in same year; payments for other services based on state’s traditional Medicaid plan | None | Based on state plana | None |

| Annual deductible | $2,500 | None | None | |

| Health savings accounts | $2,500 allowance in account used to meet deductible before other plan benefits become effective; enrollees who make payments on time can roll over any unused portion and use it to reduce monthly payments in the following year | None | None | |

| Penalty for failure to make payments | Those with incomes 101–138% of FPL are disenrolled and locked out of the program for 6 months; those with incomes ≤100% of FPL are moved from HIP Plus to HIP Basic, with higher cost sharing and fewer benefits | Not applicable | Not applicable | |

|

| ||||

| BENEFITS | ||||

|

| ||||

| State’s traditional Medicaid plan | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Vision or dental | No | Yes | Yes | Yesb |

| Other | Less generous prescription drug benefit | More generous prescription drug benefit | ||

SOURCES Authors’ analysis of data from the following sources: (1) Musumeci M, et al., An early look at Medicaid expansion waiver implementation in Michigan and Indiana (see note 7 in text). (2) Zylla E, et al. Section 1115 Medicaid expansion waivers (see note 37 in text). (3) Brooks T, Wagnerman K, Artiga S, Cornachione E, Ubri P. Medicaid and CHIP eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost-sharing policies as of January 2017: findings from a 50-state survey [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2017 Jan 12 [cited 2018 May 21]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-enrollment-renewal-and-cost-sharing-policies-as-of-january-2017-findings-from-a-50-state-survey/. (4) Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid financial eligibility: primary pathways for the elderly and people with disabilities [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): KFF; 2010 Feb 25 [cited 2018 May 21]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-financial-eligibility-primary-pathways-for-the-elderly-and-people-with-disabilities/. NOTES Indiana and Ohio expanded eligibility for Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act; Kansas did not. Healthy Indiana Program (HIP) 2.0 Basic and Plus are explained in greater detail in the text. Information on pregnancy-related coverage is not included. FPL is federal poverty level.

Section 1931 parents: $3 for nonemergency emergency department (ED) visits, $2 for preferred brand-name drug prescriptions, and $3 for nonpreferred brand-name drug prescriptions. Expansion adults: $3 for nonpreferred brand-name drug prescriptions.

Some managed care plans cover vision and dental services.

Indiana’s waiver program, HIP 2.0, built upon an earlier smaller waiver program (known retrospectively as HIP 1.0) and features two variations of Medicaid coverage, HIP Basic and HIP Plus. Eligibility is the same in the two variations, although only HIP Basic entails cost sharing in the form of graduated copayments for certain services. HIP Plus provides more generous prescription drug coverage than HIP Basic does, as well as other benefits not covered by HIP Basic—including vision and dental services. Those who enroll in HIP 2.0 and make their first payment (which is essentially a premium, though some state materials refer to this as a “POWER account contribution”) initially receive benefits provided through HIP Plus. It has a $2,500 deductible, coupled with a state- and consumer-funded $2,500 POWER account (similar to a health savings account) whose funds must be used to pay for health care services before the insurance benefit kicks in. Applicants with incomes of 101–138 percent of poverty who do not make their original POWER account contributions within sixty days are never enrolled in the program; those with incomes up to 100 percent of poverty who never make a contribution are enrolled in HIP Basic.13

To maintain enrollment in HIP Plus, members are required to continue making monthly POWER account contributions equal to 2 percent of their income. Members with incomes up to 100 percent of poverty who fail to make payments for three consecutive months are moved from HIP Plus to HIP Basic. Members with incomes of 101–138 percent of poverty who fail to make payments for three consecutive months are removed from HIP 2.0 and “locked out” of Medicaid for six months (individuals deemed “medically frail” cannot be locked out of coverage). Any unspent POWER funds are rolled over at year’s end, reducing the contribution required in the following year.

STUDY SAMPLE

Our sample consisted of non-elderly adults with family incomes at or below 138 percent of poverty, the cutoff for the ACA’s Medicaid expansion. We oversampled in Indiana and Kansas, given our intention to ask additional state-specific questions in those states.

SURVEY DESIGN

We contracted with a survey research firm to conduct a random-digit-dialed telephone survey of low-income residents in Indiana, Kansas, and Ohio. The survey instrument was pretested in a population similar to our sampled respondents and then fielded between November 9, 2017, and January 2, 2018. All but eleven surveys (0.4 percent) were completed in 2017, and excluding those eleven surveys had minimal effect on our findings. Inclusion criteria were being a US citizen ages 19–64 and having a family income at or below 138 percent of poverty. The survey was conducted in English or Spanish and via cell and landline phones. The response rate was 15 percent overall (12 percent in Indiana, 17 percent in Kansas, and 14 percent in Ohio), according to response rate 3 (RR3) definition of the American Association for Public Opinion Research.

OUTCOMES

We measured several outcomes in all three states: source of health insurance; having a personal doctor; delays in care due to cost in the past twelve months; and needing to borrow money, skip paying medical bills, or skip paying other bills due to medical bills in the past twelve months (see the online appendix methods for survey questions and additional details).19 The survey asked whether respondents felt that they had been hurt or helped by the ACA or had experienced no effect and asked them to rate the quality of their health care over the past six months on a scale of 0 to 10, a question obtained from a recent Medicaid survey conducted by CMS.20

For respondents in Indiana, we asked state-specific questions of two coverage groups. Those with Medicaid whose responses indicated that they were eligible for HIP 2.0 (that is, people who were neither pregnant nor eligible for Medicaid due to a disability) were asked about their knowledge, use, and perception of POWER accounts. We asked currently uninsured people in Indiana for their primary reason for not enrolling in HIP 2.0. For respondents in Kansas, our state-specific outcomes of interest were whether they supported or opposed Medicaid expansion, how they perceived the quality of care with Medicaid compared to private insurance or being uninsured, their employment and disability status, and whether they would be more likely to look for work as a condition of Medicaid eligibility. Because of survey length constraints, we asked about work requirements in Kansas only.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All responses were weighted to match state-specific population benchmarks in the 2016 American Community Survey for education, race/ethnicity, marital status, geographic region, population density, and cell phone status.

Survey-weighted descriptive statistics were computed for all outcomes. Then, for binary outcomes, we used multivariate logistic regression, and for the only continuous measure (quality of care), we used multivariate linear regression to identify significant predictors of each outcome. These models included the following covariates: state of residence, age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, rural versus urban residence, sex, political party affiliation, marital status, and family income. Analyses of outcomes assessed within a single state (for example, work requirements in Kansas and HIP 2.0 experiences in Indiana) were similar except that they did not include the state as a covariate.

All analyses were conducted using Stata, version 15. We used the “margins” command to generate predicted probabilities from our regression models for ease of interpretation.

LIMITATIONS

Our study had several limitations. First, the response rate was 15 percent. However, our use of population benchmarks for weighting has been shown to reduce the potential nonresponse bias in random-digit-dialed surveys.21 Additionally, results in previous research using a similar instrument have been validated against two federal government surveys, which demonstrated similar overall patterns of coverage and access to care.9 More broadly, our response rate compares favorably to those of other surveys that are frequently used to evaluate the ACA.22,23

Second, our three-state comparisons relied on cross-sectional state differences, which can be biased by numerous unmeasured factors that differ between states despite multivariate adjustment. However, our results are quite similar to those of numerous more rigorous quasi-experimental comparisons between expansion and nonexpansion states for similar outcomes.1–5

Third, many of our state-specific questions, such as those related to Indiana’s POWER accounts, were asked of relatively few people. However, our sample size in Indiana was similar to or larger than those of two prior studies of HIP 2.0.7,13

Fourth, we asked respondents in Indiana whether they had heard of or were aware of POWER accounts. It is possible that some respondents did not know the program’s name or features but were still making payments (or receiving third-party assistance with plan payments), which would lead us to underestimate participation rates in that part of the program.

Fifth, our analysis of employment focused only on Kansas, based on survey length considerations in each state and the total study budget. However, work requirements are clearly also relevant in Indiana (which has received approval to implement them) and Ohio (which has proposed doing so). Moreover, our survey did not assess the reasons why people might not be working, though these issues have been evaluated in other research.16

Finally, type of insurance coverage was self-reported. Respondents might have incorrectly reported their type of coverage, particularly in Indiana—since confusion among HIP 2.0 beneficiaries is a major challenge.7 We tried to mitigate the effects of this by including multiple state-specific names in the survey (for example, Medicaid, HIP 2.0, and Healthy Indiana). But we cannot exclude the possibility that measurement error affected our estimates.

Study Results

Our sample consisted of 2,739 people—1,007 in Indiana, 1,000 in Kansas, and 732 in Ohio. (Appendix exhibit 1 presents descriptive statistics.)19 The sample in Ohio had a higher share (33 percent) of racial/ethnic minorities than those in the other states (26 percent in Indiana and 27 percent in Kansas), while the Kansas sample was disproportionately rural (48 percent) compared to Indiana (27 percent) and Ohio (17 percent).

THREE-STATE COMPARISONS OF COVERAGE, ACCESS, AND SATISFACTION

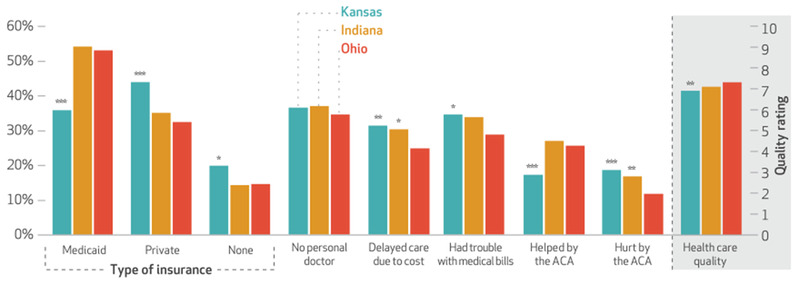

Exhibit 2 shows differences in coverage, access to care, attitudes toward the ACA, and ratings of overall health care quality across the three states, after adjustment for sociodemographic features. We found significantly higher rates of Medicaid coverage (53.1 percent versus 35.9 percent; p < 0.001) and lower uninsurance rates (14.7 percent versus 19.9 percent; p = 0.06) in Ohio compared to Kansas, but no significant differences between the two expansion states (Ohio and Indiana). Rates of having a personal doctor were similar in all three states. Rates of delaying care due to cost were higher in Kansas (p = 0.04) and Indiana (p = 0.06) than in Ohio. Respondents in Kansas were less likely to say that the ACA had helped them, compared to respondents in Ohio and Indiana, while those in Kansas and Indiana were more likely to say that the ACA had hurt them, compared to those in Ohio. Average health care ratings (on a 0–10 scale) were highest in Ohio and lowest in Kansas (7.3 versus 6.9; p = 0.03), with Indiana in between (7.1; p = 0.22 compared to Ohio). (Appendix exhibit 2 shows full regression results for selected outcomes.)19

EXHIBIT 2.

Coverage, access, and health care experiences of low-income adults in Indiana, Kansas, and Ohio, 2017

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of survey responses from 2,739 US citizens ages 19–64 with incomes below 138 percent of the federal poverty level. NOTES All responses are survey weighted to produce representative estimates. Results are regression adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, political identification, marital status, educational attainment, sex, family income, and rurality. Significance refers to differences with respondents from Ohio (the reference group). ACA is Affordable Care Act. *p < 0.10 **p < 0.05 ***p < 0.01

CONSUMER EXPERIENCE IN THE HEALTHY INDIANA PLAN

Among respondents in Indiana who reported having Medicaid coverage and who were likely enrolled in HIP 2.0 (that is, they were not receiving disability-related income or pregnant), 39 percent said that they had not heard of the POWER accounts, 26 percent had heard of them but were not consistently making required payments, and 36 percent were making regular payments (exhibit 3). The most common reason for nonpayment was affordability (31 percent), while 22 percent of respondents said that they didn’t think the additional benefits were worth the money, and 19 percent were confused about the accounts.

EXHIBIT 3.

Knowledge of and experiences with the Healthy Indiana Plan (HIP) 2.0 among low-income adults in Indiana, 2017

| Variable | Percent |

|---|---|

| Eligibility for HIP 2.0 among adults with Medicaid (n = 578) | |

| Receiving disability-related incomea | 36.2 |

| Pregnant | 1.6 |

| Likely eligible for HIP 2.0 | 62.2 |

|

| |

| Among those with Medicaid eligible for HIP 2.0 (n = 296): heard of POWER account | |

| No | 39.0 |

| Yes, and making regular payments to account | 35.6 |

| Yes, but not making regular payments to accountb | 25.5 |

|

| |

| Reasons for nonpayment (n = 56) | |

| Could not afford payments | 30.6 |

| Other | 26.2 |

| Did not think benefits were worth payment | 21.6 |

| Confused by POWER accounts | 19.1 |

| Forgot | 2.5 |

|

| |

| Among those who have heard of POWER accounts (n = 196): “The POWER account helps me think about the health services I really need” | |

| Strongly agree | 25.1 |

| Agree | 32.0 |

| Neutral/don’t know | 17.1 |

| Disagree | 14.5 |

| Strongly disagree | 11.3 |

|

| |

| Among those who have heard of POWER accounts (n = 196): “The POWER account is hard to understand or has made it more difficult for me to get the health care I need” | |

| Strongly agree | 18.9 |

| Agree | 20.9 |

| Neutral/don’t know | 12.7 |

| Disagree | 18.5 |

| Strongly disagree | 29.1 |

|

| |

| Among uninsured adults (n = 122): reasons not enrolled in HIP 2.0 | |

| Unaffordable | 29.6 |

| Do not think I qualify | 20.3 |

| Too complicated | 17.3 |

| “Locked out” because of POWER account nonpayment | 8.6 |

| Don’t know | 24.3 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of survey responses from US citizens ages 19–64 with incomes below 138 percent of the federal poverty level. NOTES All responses were survey weighted to produce representative estimates. POWER is Personal Wellness and Responsibility account.

Social Security Disability Insurance or Supplemental Security Income.

Respondents were asked, “Do you pay a premium or put money into your POWER account on a regular basis?”

Among those familiar with the POWER accounts, 57 percent agreed or strongly agreed that their account “helps me think about the health services I really need,” while 40 percent agreed or strongly agreed that the accounts were hard to understand or made it difficult to obtain necessary care. Nine percent of uninsured respondents in Indiana reported that they had been locked out of coverage as a result of premium nonpayment.

We found that various demographic characteristics served as predictors of several of these outcomes (appendix exhibit 3).19 Among Indiana Medicaid beneficiaries, Latinos, men, and those with less education were significantly less likely to have heard about the POWER accounts than whites, women, and those with more education, respectively. Younger adults were more critical of the accounts than adults ages forty-five and older.

ATTITUDES ABOUT MEDICAID EXPANSION AND WORK REQUIREMENTS IN KANSAS

Three-fourths of respondents in Kansas supported Medicaid expansion in the state, and just 11 percent were opposed (exhibit 4). More than two-thirds said that they would receive higher-quality care if they had Medicaid than if they had no insurance, and only 9 percent said that the quality of care under Medicaid was worse than that with no coverage. In a comparison of Medicaid and private insurance, 32 percent said that quality was better with Medicaid, 31 percent said that it was better with private coverage, and 37 percent felt that it was similar with either type of insurance.

EXHIBIT 4.

Views of coverage expansion and work requirements among low-income adults in Kansas

| Percent | |

|---|---|

| In favor of Medicaid expansion in Kansas | |

| Yes | 77.0 |

| No | 11.3 |

| Don’t know | 11.4 |

|

| |

| Quality of care | |

| Medicaid versus no insurance | |

| Better with Medicaid | 67.9 |

| No difference | 23.1 |

| Better with no insurance | 9.0 |

| Medicaid versus private insurance | |

| Better with Medicaid | 31.8 |

| No difference | 37.0 |

| Better with private insurance | 31.3 |

|

| |

| Work status | |

| All respondents | |

| Employed | 60.2 |

| Disabled | 25.9 |

| Not working, would look for work if required | 8.8 |

| Not working, would not look for work if required | 5.2 |

| Respondents with Medicaid or no insurance (n = 586) | |

| Employed | 48.7 |

| Disabled | 34.1 |

| Not working, would look for work if required | 11.1 |

| Not working, would not look for work if required | 6.0 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of survey responses from US citizens ages 19–64 with incomes below 138 percent of the federal poverty level. NOTES For all questions, n = 1,000 minus item nonresponse, except where indicated. All responses are survey weighted to produce representative estimates.

Work requirements would affect a fairly small share of the state’s potential Medicaid population. Of those with Medicaid currently or without any coverage (who would presumably be eligible if the state expanded Medicaid), 49 percent reported that they were working, and 34 percent had a disability that kept them from working. Eleven percent were not working but said that they would be more likely to look for a job if that was required as a condition of obtaining Medicaid; 6 percent were not working and said that they would not be more likely to look for work even if required. A multivariate analysis (appendix exhibit 4)19 indicated that among those not working, a Medicaid work requirement would significantly increase rates of job seeking among single adults, Latinos, and people living in rural areas.

Discussion

With more than a dozen states proposing or implementing new Medicaid waivers over the past three years, evaluating low-income adults’ experiences in and attitudes toward waiver program features is critical. Using data from a novel survey of more than 2,700 low-income adults in three states, we found a mixed picture of the current and potential future effects of several waiver provisions.

WAIVER-BASED MEDICAID EXPANSION

Three years into the implementation of the consumer-based Healthy Indiana Plan, HIP 2.0, we found that nearly 40 percent of beneficiaries likely eligible for the program were unaware of the existence of the required POWER accounts that are one of the state’s key innovations. Given that another 26 percent of respondents were not making regular payments to their accounts, we estimate that as many as two-thirds of recipients could be at risk for losing benefits such as vision and dental care or being temporarily locked out of the program.

In touting HIP’s success, officials have said that “70 percent of HIP members make POWER account contributions.”24 This appears to refer to a state evaluation conducted by the Lewin Group,13 which reported a 29 percent rate of disenrollment from the program among those subject to that penalty (that is, people with incomes of 101–138 percent of poverty and not medically frail). However, this is not the same as the overall share of people who signed up for HIP who paid their premiums. This estimate excluded HIP Basic members, most of whom never made any payments and thus weren’t enrolled in HIP Plus in the first place. Elsewhere in the Lewin report, as highlighted by the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation in a critique of that evaluation,25 two broader measures of payment rates were reported: 57 percent of those with incomes at or below 100 percent of poverty were moved to HIP Basic for nonpayment, and 51 percent of those with incomes above 100 percent of poverty who applied for and were deemed eligible for HIP 2.0 did not make premium payments—figures that are much closer to our estimates. In addition, the Lewin survey had a lower response rate (4.8 percent) than our survey did, and it did not use demographic weighting to reduce non-response bias.13

Troublingly, we found that lack of awareness of the program was highest among Latinos and less-educated adults, which could exacerbate disparities compared to traditional Medicaid. Meanwhile, 9 percent of uninsured respondents in Indiana reported being locked out of benefits because they did not make POWER account payments as required.

These findings are consistent with findings from studies of Medicaid waivers in Iowa and Michigan, which indicate that many enrollees do not participate in consumer-directed provisions in their states’ Medicaid expansions, often because of confusion or lack of awareness.7,26 In Michigan, fewer than 20 percent of Medicaid enrollees participated in a mandatory health risk assessment,27 and as of July 2016, more than 100,000 Healthy Michigan enrollees had past due out-of-pocket payments.7 In Iowa, just 17 percent of enrollees completed the program’s health-promoting activities (such as a wellness exam and health risk assessment), and one of the primary drivers of nonparticipation was lack of information.26 Researchers also found that disenrollment (typically for premium nonpayment) in Iowa led to financial hardship and barriers to care.28

While only a minority of Indiana residents with Medicaid knew about and were making regular payments to POWER accounts, many in this subgroup had favorable opinions of the accounts. Fifty-seven percent of respondents familiar with the accounts reported that the program helped them think about which health care services they needed. Increasing cost-based awareness and consumerism in health care was one of the chief arguments the program’s creators put forward in favor of Indiana’s waiver approach,24 and that goal was met for the minority of beneficiaries who understood and paid into the program. However, taking into account the substantial confusion about Indiana’s program and its cost-sharing requirements, it is perhaps not surprising that difficulties affording care were higher in Indiana than in Ohio, which implemented a traditional Medicaid expansion with minimal cost sharing. While we found similar overall coverage rates in Indiana and Ohio, a recent study using a larger national data set found that Indiana’s coverage gains lagged behind those of its Midwestern neighbors, perhaps in part because of HIP 2.0’s cost-sharing requirements.29

Interestingly, Indianans were also more likely than Ohioans to report that the ACA had hurt them, though our results do not enable us to determine what led to this disparity in perceptions of the law. While Indiana modified aspects of HIP in its waiver renewal approved by CMS in February 2018 (including the addition of work requirements for 2019), the core features we evaluated here—the POWER accounts and lockout periods—remain in effect.

EXPANSION VERSUS NONEXPANSION

In Kansas, which has yet to expand Medicaid, we found very strong support for expansion among low-income adults in that state. This is consistent with public opinion in prior national and single-state studies.30,31 While most respondents agreed that having Medicaid was better than being uninsured, there was no clear preference for Medicaid versus private coverage in terms of quality of care.

Our cross-state comparisons demonstrate that the uninsurance rate, cost-related barriers to care, health care ratings, and problems paying medical bills were all significantly worse among low-income adults in Kansas, compared to those in Ohio—which had a traditional expansion of Medicaid. While these findings are only cross-sectional (albeit adjusted for sociodemographic factors), the basic pattern is consistent with quasi-experimental studies of expansion versus non-expansion states that have shown significant gains in coverage and access to and affordability of care after Medicaid expansion.2–5

WORK REQUIREMENTS

Our results in Kansas also shed light on the push for Medicaid work requirements in several states. Consistent with prior analyses,16,17,32 our study showed that most potential Medicaid beneficiaries are either already working or disabled. We add a new finding to this literature: Only 11 percent of potential Medicaid beneficiaries reported that a work requirement would have any effect on their looking for a job, though this did represent more than half of the 17 percent who were not working and were not disabled. Notably, this potential effect was disproportionately reported by rural adults—which raises questions as to the availability of employment for people who would look for work if required, given the paucity of new jobs in rural areas over the past decade.33

Advocates of work requirements have pointed to the positive association between employment and health to argue that the policy could improve Medicaid health outcomes by inducing more beneficiaries to work34 (though the causality of this relationship is unclear). Our findings suggest that work requirements would likely produce modest impacts on job-searching behavior in this population, inducing some people to look for jobs but not changing the likelihood of employment for the vast majority (nearly 90 percent) of people who might enroll in Medicaid. This builds on prior evidence that the ACA’s Medicaid expansion has had no detectable impact to date on employment decisions among low-income adults.35,36

ADMINISTRATIVE COSTS

While our findings do not shed light directly on the costs of administering health savings accounts or work requirements, such costs are another consideration for Indiana’s POWER accounts and potential work requirements in Kansas or any other state. Implementing these alternative approaches requires additional resources. Even though the POWER accounts in Indiana built upon HIP 1.0, the predecessor of HIP 2.0, the expansion substantially increased per beneficiary administrative requirements. One study indicated that Indiana’s Medicaid managed care organizations had to increase administrative staffing ratios and devote more time to meet the state’s requirements for oversight of the POWER accounts.37 While Indiana officials have not released estimates of the program’s administrative costs, officials in Arkansas estimated that administrative costs for that state’s health savings accounts in Medicaid were over $1,100 per participating beneficiary per year.37

The costs to states of these accounts may outweigh the relatively modest benefits noted among some Indiana respondents in our survey. Similarly, a work requirement that changes behavior for only a tenth of the population but requires verification of employment or exemptions for medical frailty and other hardships for the vast majority of beneficiaries also raises concerns about administrative efficiency.16

Our findings suggest that work requirements would likely produce modest impacts on job-searching behavior in this population.

Of course, these administrative costs may ultimately be outweighed in the Medicaid budget if total enrollment falls substantially as a result of these requirements, which may be another reason that states are considering these changes. While some people would lose coverage because they chose not to comply with the new requirements (for example, to look for work, contribute to a health savings account, or make premium payments), others may be dissuaded from applying or be removed from the Medicaid rolls because of the added administrative difficulty of applying or reenrolling, even though they may meet the program’s requirements.8

Conclusion

Among low-income adults in three Midwestern states, we found that coverage rates and access to care were significantly higher in the expansion states (Indiana and Ohio) than the nonexpansion state (Kansas), but there was also some evidence that Indiana’s waiver program led to less affordable care than Ohio’s traditional expansion of Medicaid did. Consumers’ confusion about the Healthy Indiana Plan and difficulty paying premiums may have offset benefits among the subset of enrollees who perceived the health savings accounts to be helpful. Low-income Kansans strongly supported Medicaid expansion in their state, while a work requirement would have effects on job-seeking behavior for approximately 10 percent of the potential Medicaid population. These findings suggest that current Medicaid innovations may lead to unintended consequences for coverage and access and that ongoing independent monitoring of their effects is essential.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Results from this study will be presented at the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting in Seattle, Washington, on June 25, 2018. This project was supported by research grants from the Commonwealth Fund and the REACH Healthcare Foundation. Carrie Fry completed this project while on a training grant from the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health (Grant No. T32MH019733). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the views of the Commonwealth Fund, the REACH Healthcare Foundation, or the National Institutes of Health. [Published online June 20, 2018.]

NOTES

- 1.Kominski GF, Nonzee NJ, Sorensen A. The Affordable Care Act’s impacts on access to insurance and health care for low-income populations. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:489–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sommers BD, Maylone B, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Three-year impacts of the Affordable Care Act: improved medical care and health among low-income adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(6):1119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller S, Wherry LR. Health and access to care during the first 2 years of the ACA Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med 2017;376(10):947–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon K, Soni A, Cawley J. The impact of health insurance on preventive care and health behaviors: evidence from the first two years of the ACA Medicaid expansions. J Policy Anal Manage. 2017;36(2):390–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Courtemanche Ch, Marton J, Ukert B, Yelowitz A, Zapata D. Early impacts of the Affordable Care Act on health insurance coverage in Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states. J Policy Anal Manage. 2017;36(1):178–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loehrer AP, Chang DC, Scott JW, Hutter MM, Patel VI, Lee JE, et al. Association of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion with access to and quality of care for surgical conditions. JAMA Surg 2018;153(3):e175568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Musumeci M, Rudowitz R, Ubri P, Hinton E. An early look at Medicaid expansion waiver implementation in Michigan and Indiana [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2017. January 31 [cited 2018 May 21]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/an-early-look-at-medicaid-expansion-waiver-implementation-in-michigan-and-indiana [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carroll AE. The problem with work requirements for Medicaid. JAMA. 2018;319(7):646–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sommers BD, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Changes in utilization and health among low-income adults after Medicaid expansion or expanded private insurance. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176(10):1501–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson JW, Goudie A, Self J, White V, Leath K, Ramirez L, et al. Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (“private option”) section 1115 demonstration waiver interim report [Internet]. Little Rock (AR): Arkansas Center for Health Improvement; 2016. March 30 [cited 2018 May 21]. Available from: http://www.achi.net/Content/Documents/ResourceRenderer.ashx?ID=347 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groppe M. Seema Verma, Trump’s pick to head Medicare and Medicaid, avoids giving policy views. USA Today [serial on the Internet]. 2017. February 16 [cited 2018 May 21]. Available from: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2017/02/16/pick-head-medicare-medicaid-avoids-giving-policy-views/98008830

- 12.Galewitz P. Pence expanded Medicaid as governor, now he may be part of cutting it. WFDD National Public Radio [serial on the Internet]. 2016. November 23 [cited 2018 May 21]. Available from: https://wfdd-test.kilpho.st/story/pence-expanded-medicaid-governor-now-he-may-be-part-cutting-it

- 13.Lewin Group. Healthy Indiana Plan 2.0: POWER account contribution assessment [Internet]. Indianapolis (IN): Indiana Family and Social Services Administration; 2017. March 31 [cited 2018 May 21]. Available from: https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/in/Healthy-Indiana-Plan-2/in-healthy-indiana-plan-support-20-POWER-acct-cont-assesmnt-03312017.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harper J. Indiana’s claims about its Medicaid experiment don’t all check out. National Public Radio [serial on the Internet]. 2017. February 24 [cited 2018 May 21]. Available from: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/02/24/516704082/indiana-s-claims-about-its-medicaid-program-dont-all-check-out

- 15.Dickson V. CMS scales back evaluation plans for Indiana Medicaid waiver. Modern Healthcare [serial on the Internet]. 2018. April 9 [cited 2018 May 21]. Available from: http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20180409/NEWS/180409915

- 16.Garfield R, Rudowitz R, Damico A. Understanding the intersection of Medicaid and work [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; [updated 2018 Jan 5; cited 2018 May 21]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/understanding-the-intersection-of-medicaid-and-work/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tipirneni R, Goold SD, Ayanian JZ. Employment status and health characteristics of adults with expanded Medicaid coverage in Michigan. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178(4):564–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodnough A, Smith M. Kansas governor vetoes Medicaid expansion, setting stage for showdown. New York Times. 2017. March 31; Sect. A:10. [Google Scholar]

- 19.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 20.Barnett ML, Sommers BD. A national survey of Medicaid beneficiaries’ experiences and satisfaction with health care. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177(9):1378–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pew Research Center. Assessing the representativeness of public opinion surveys [Internet]. Washington (DC): Pew Research Center; 2012. May 15 [cited 2018 May 22]. Available from: http://www.people-press.org/2012/05/15/assessing-the-representativeness-of-public-opinion-surveys/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skopec L, Musco T, Sommers BD. A potential new data source for assessing the impacts of health reform: evaluating the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index. Healthc (Amst). 2014;2(2):113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long SK, Kenney GM, Zuckerman S, Goin DE, Wissoker D, Blavin F, et al. The Health Reform Monitoring Survey: addressing data gaps to provide timely insights into the Affordable Care Act. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(1):161–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verma S, Neale B. Healthy Indiana 2.0 is challenging Medicaid norms. Health Affairs Blog [blog on the Internet]. 2016. August 29 [cited 2018 May 22]. Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20160829.056228/full/

- 25.Rudowitz R, Musumeci M, Hinton E. Digging into the data: what can we learn from the state evaluation of Healthy Indiana (HIP 2.0) premiums [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018. March 8 [cited 2018 May 22]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/digging-into-the-data-what-can-we-learn-from-the-state-evaluation-of-healthy-indiana-hip-2-0-premium [Google Scholar]

- 26.Askelson NM, Wright B, Bentler S, Momany ET, Damiano P. Iowa’s Medicaid expansion promoted healthy behaviors but was challenging to implement and attracted few participants. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(5):799–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Udow-Phillips M, Lausch KB, Shigekawa E, Hirth R, Ayanian J. The Medicaid expansion experience in Michigan. Health Affairs Blog [blog on the Internet]. 2015. August 28 [cited 2018 May 22]. Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20150828.050226/full/

- 28.Askelson N, Wright B, Smith R, Brady P, Bentler S, Damiano P, et al. Healthy Behaviors dis-enrollment interviews report: in-depth interviews with Iowa Health and Wellness Plan members who were recently disenrolled due to failure to pay required premiums [Internet]. Iowa City (IA): University of Iowa Public Policy Center; 2017. January [cited 2018 May 22]. Available from: http://ppc.uiowa.edu/sites/default/files/ihawp_disenrollee_report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freedman S, Richardson L, Simon KI. Learning from waiver states: coverage effects under Indiana’s HIP Medicaid expansion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(6):936–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Epstein AM, Sommers BD, Kuznetsov Y, Blendon RJ. Low-income residents in three states view Medicaid as equal to or better than private coverage, support expansion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(11):2041–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collins SR, Rasmussen PW, Doty MM, Garber T. What Americans think of the new insurance Market-places and Medicaid expansion [Internet]. New York (NY): Commonwealth Fund; 2013. September [cited 2018 May 22]. Available from: http://www.commonwealthfund.org//media/files/publications/issue-brief/2013/sep/1708_collins_hlt_ins_marketplace_survey_2013_rb_final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ku L, Brantley E. Myths about the Medicaid expansion and the “able bodied.” Health Affairs Blog [blog on the Internet]. 2017. March 6 [cited 2018 May 22]. Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20170306.059021/full/

- 33.Thiede B, Greiman L, Weiler S, Beda SC, Conroy T. Six charts that illustrate the divide between rural and urban America. The Conversation [serial on the Internet]. [Cited 2018 May 22]. Available from: https://theconversation.com/six-charts-that-illustrate-the-divide-between-rural-and-urban-america-72934

- 34.Huberfeld N. Can work be required in the Medicaid program? N Engl J Med 2018;378(9):788–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gooptu A, Moriya AS, Simon KI, Sommers BD. Medicaid expansion did not result in significant employment changes or job reductions in 2014. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(1):111–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moriya AS, Selden TM, Simon KI. Little change seen in part-time employment as a result of the Affordable Care Act. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(1):119–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zylla E, Planalp C, Lukanen E, Blewett L. Section 1115 Medicaid expansion waivers: implementation experiences [Internet]. Washington (DC): Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission; 2018. February 8 [cited 2018 May 21]. Available from: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/SECTION-1115-MEDICAID-EXPANSION-WAIVERS_-IMPLEMENTATION-EXPERIENCES.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.