Key Points

Question

What was the pattern for site of death, place of care, and health care transitions and burdensome care that occurred between 2000 and 2015 for Medicare beneficiaries?

Findings

In a retrospective cohort study of a 20% sample of the Medicare fee-for-service population that included 1 361 870 decedents, the site of care changed between 2000 and 2015 from acute care hospitals to the community. The proportion of deaths that occurred in acute care hospitals decreased to 19.8%, intensive care unit use during the last 30 days of life increased and then stabilized at approximately 29%, and health care transitions during the last 3 days of life decreased after 2009.

Meaning

Among Medicare beneficiaries who died between 2000 and 2015, there was a decrease in the rates of death that occurred in the hospital, with an increase and then stabilization of the rates of intensive care unit use, and an increase and then decline in health care transitions during the last 3 days of life.

Abstract

Importance

End-of-life care costs are high and decedents often experience poor quality of care. Numerous factors influence changes in site of death, health care transitions, and burdensome patterns of care.

Objective

To describe changes in site of death and patterns of care among Medicare decedents.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective cohort study among a 20% random sample of 1 361 870 decedents who had Medicare fee-for-service (2000, 2005, 2009, 2011, and 2015) and a 100% sample of 871 845 decedents who had Medicare Advantage (2011 and 2015) and received care at an acute care hospital, at home or in the community, at a hospice inpatient care unit, or at a nursing home.

Exposures

Secular changes between 2000 and 2015.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Medicare administrative data were used to determine site of death, place of care, health care transitions, which are changes in location of care, and burdensome patterns of care. Burdensome patterns of care were based on health care transitions during the last 3 days of life and multiple hospitalizations for infections or dehydration during the last 120 days of life.

Results

The site of death and patterns of care were studied among 1 361 870 decedents who had Medicare fee-for-service (mean [SD] age, 82.8 [8.4] years; 58.7% female) and 871 845 decedents who had Medicare Advantage (mean [SD] age, 82.1 [8.5] years; 54.0% female). Among Medicare fee-for-service decedents, the proportion of deaths that occurred in an acute care hospital decreased from 32.6% (95% CI, 32.4%-32.8%) in 2000 to 19.8% (95% CI, 19.6%-20.0%) in 2015, and deaths in a home or community setting that included assisted living facilities increased from 30.7% (95% CI, 30.6%-30.9%) in 2000 to 40.1% (95% CI, 39.9%-30.3% ) in 2015. Use of the intensive care unit during the last 30 days of life among Medicare fee-for-service decedents increased from 24.3% (95% CI, 24.1%-24.4%) in 2000 and then stabilized between 2009 and 2015 at 29.0% (95% CI, 28.8%-29.2%). Among Medicare fee-for-service decedents, health care transitions during the last 3 days of life increased from 10.3% (95% CI, 10.1%-10.4%) in 2000 to a high of 14.2% (95% CI, 14.0%-14.3%) in 2009 and then decreased to 10.8% (95% CI, 10.6%-10.9%) in 2015. The number of decedents enrolled in Medicare Advantage during the last 90 days of life increased from 358 600 in 2011 to 513 245 in 2015. Among decedents with Medicare Advantage, similar patterns in the rates for site of death, place of care, and health care transitions were observed.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who died in 2015 compared with 2000, there was a lower likelihood of dying in an acute care hospital, an increase and then stabilization of intensive care unit use during the last month of life, and an increase and then decline in health care transitions during the last 3 days of life.

This population epidemiology study characterizes trends in care in the intensive care unit during the last 30 days of life and in posthospital transitions and site of death among Medicare beneficiaries who died between 2000 and 2015.

Introduction

Important quality concerns have been noted with the medical care of seriously ill patients, especially during the last weeks of life.1,2,3 Research has found poor palliation of symptoms,4 burdensome health care transitions during the last days of life,1 reports of unmet patient needs,4 concerns with the quality of care,5 and declines in the ratings for patient care quality.

An important concern in US health care policy involves the high cost of health care and the adequacy of care quality provided to seriously ill “high-need, high-cost” patients; in the United States, 5% of persons account for 60% of health care expenditures.6,7 Death is usually preceded by prolonged illness, and about 80% of individuals are considered high-need, high-cost patients prior to death.

Previous research involving decedents between 2000 and 2009 with Medicare fee-for-service found that even though the proportion of individuals who died in an acute care hospital decreased from 32.6% to 24.6%, intensive care unit (ICU) use during the last month of life increased from 24.3% to 29.2% and health care transitions during the last 3 days of life increased from 10.3% to 14.2%.1 These changes in care use occurred despite secular changes in the US health care system such as the expansion of hospice services,8 inpatient palliative care teams,9 and increases in staffing of hospitals with hospitalists.10

Since 2009, policies and programs ranging from ensuring informed patient decision making to enhanced care coordination have had the goal of improving care at the end of life. Specific interventions have included promoting conversations about the goals of care, continued growth of hospice services and palliative care, and the debate and passage of the Affordable Care Act. It is unknown whether these continued efforts and new policy changes implemented under the Affordable Care Act have affected medical care at the end of life.

Methods

Data and Study Population

This study used Medicare enrollment and claims data and nursing home assessment data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Minimum Data Set that are covered under the terms of CMS data use agreement RSCH-2015-28232. The institutional review boards at Brown University and Oregon Health & Science University reviewed the study and waived informed consent.

A 20% random sample of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who died in 2000, 2005, 2009, 2011, and 2015 was created based on the Medicare Beneficiary Eligibility and Enrollment file to match the inclusion and exclusion criteria of a previous study.1 The Medicare fee-for-service cohorts included persons aged 66 years or older with fee-for-service Part A and Part B coverage during the last year of life. Because of the increasing growth of Medicare Advantage, a sensitivity analysis was done comparing Medicare Advantage with Medicare fee-for-service in 2011 and 2015.

All of the Medicare Advantage decedents had insurance coverage during the last 90 days of life. Medicare Advantage decedents were included because hospitals began submitting encounter records for all Medicare beneficiaries starting in 2008, including those with Medicare Advantage, which allowed the CMS to calculate disproportionate share payments and indirect and direct medical education adjustment.11 These claims were present with the exception of beneficiaries discharged from hospitals that were not required to submit this information. These included critical access hospitals and those hospitals that care only for patients with Medicare Advantage. A recent study found that these hospitals accounted for 92% of Medicare discharges between 2011 and 2013.12

This study focused on changes in patterns among Medicare fee-for-service decedents. In addition, the differences between Medicare Advantage and Medicare fee-for-service decedents were presented as a sensitivity analysis. However, there are no published estimates of the accuracy of these informational claims.

Outcomes

The Residential History File algorithm was used to define the outcomes.13 The Residential History File tracks beneficiaries by place and time using the dates of service on Medicare claims and Minimum Data Set assessments, and the date of death from the Medicare enrollment file. Based on the Residential History File, a health care transition was defined as a change in the place of care.

Site of death was defined for the following categories: home or community, assisted living facility coupled with home hospice, acute care hospital, nursing home, and hospice inpatient care unit. With the exception of persons who died while receiving hospice services, the use of the term home or community refers to noninstitutional settings and includes persons dying in assisted living facilities, personal care homes, and private homes. Only those who died while receiving hospice services can be characterized as dying in an assisted living facility.

In addition, several patterns of care use during the last 90 days of life were examined, including hospice services received by the time of death, hospice services received during the last 3 days of life, days of general inpatient hospice care during the last 30 days of life, continuous hospice care during the last 30 days of life, hospitalizations during the last 30 and 90 days of life, ICU use during the last 30 days of life, and nursing home use during the last 90 days of life. For all of these patterns of care use, the denominator is all deaths.

General inpatient hospice care is meant for short-term management of pain or other symptoms provided in an inpatient setting (ie, in a free-standing hospice inpatient unit, an acute care hospital, or a nursing home). Continuous home care provides similar hospice services but these services are provided in a home or in a nursing home that does not have skilled nursing facility beds. Because hospice services for Medicare Advantage beneficiaries are carved out and billed separately, hospice use is characterized for both Medicare Advantage and Medicare fee-for-service decedents.

To better understand the increase in the proportion of deaths that occurred in the home or community setting, the location of deaths in 2009, 2011, and 2015 was examined for those patients receiving hospice services that the Residential History File algorithm classified as in the home or in the community. The codes for place of service captured whether the patients who received hospice services died in an assisted living facility.

Potentially burdensome transitions were defined as transitions during the last 3 days of life; 3 or more hospitalizations during the last 90 days of life; or 2 or more hospitalizations for pneumonia, urinary tract infection, dehydration, or sepsis during the last 120 days of life. Prolonged mechanical ventilation (≥4 days) during a terminal hospitalization was defined as a type of potentially burdensome care.

Race/ethnicity was based on self-report to the Social Security Administration and was included for the purpose of interpreting the change in site of death and patterns of care. Several studies reported that black patients prefer more aggressive patterns of care than white patients.14,15,16 Other studies have suggested that Hispanic persons are more likely than white persons to die at home or in a relative’s home.17,18

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics with 95% CIs characterized the site of death, places of care, health care transitions between hospital and nursing home, and burdensome patterns of transitions during the last months of life. For each outcome, 95% CIs were calculated. The comparisons between years were interpreted as different if their 95% CIs did not overlap. A descriptive analysis characterized Medicare Advantage and Medicare fee-for-service decedents. All analyses were performed using Stata version 15 (StataCorp).

Results

The sociodemographic characteristics of 1 361 870 decedents with Medicare fee-for-service (mean [SD] age, 82.8 [8.4] years; 58.7% female) and 871 845 decedents with Medicare Advantage (mean [SD] age, 82.1 [8.5] years; 54.0% female) appear in Table 1. Race/ethnicity data were missing for only 0.21% of cases.

Table 1. Characteristics of Medicare Decedents in the Study Sample From 2000 Through 2015.

| Medicare Fee-for-Servicea | Medicare Advantageb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 (n = 270 202) | 2005 (n = 291 819) | 2009 (n = 286 282) | 2011 (n = 262 338) | 2015 (n = 251 229) | 2011 (n = 358 600) | 2015 (n = 513 245) | |

| Age, mean (SD) [IQR], y | 81.9 (8.2) [76.0-88.0] | 82.1 (9.3) [76.0-88.0] | 83.0 (8.4) [77.0-89.0] | 83.4 (8.4) [77.0-90.0] | 83.5 (8.8) [77.0-90.0] | 82.0 (8.3) [76.0-88.0] | 82.1 (8.6) [75.0-89.0] |

| Female sex, % (95% CI) | 57.0 (56.8-57.2) | 56.2 (56.0-56.4) | 60.6 (60.4-60.8) | 60.7 (60.5-60.9) | 59.3 (59.1-59.5) | 54.1 (54.0-54.3) | 53.9 (53.8-54.1) |

| Race/ethnicity, % (95% CI) | |||||||

| White | 88.7 (88.6-88.8) | 87.5 (87.4-87.7) | 88.0 (87.9-88.1) | 88.3 (88.3-88.5) | 88.2 (88.0-88.3) | 84.8 (84.7-84.9) | 83.1 (83.0-83.2) |

| Black | 8.3 (8.3-8.4) | 8.7 (8.6-8.8) | 8.0 (7.9-8.1) | 7.9 (7.8-8.0) | 7.7 (7.6-7.8) | 9.9 (9.8-10.0) | 10.6 (10.5-10.7) |

| Hispanic | 1.1 (1.0-1.1) | 1.5 (1.4-1.5) | 1.5 (1.4-1.5) | 1.4 (1.4-1.5) | 1.3 (1.3-1.3) | 2.2 (2.2-2.3) | 2.5 (2.5-2.5) |

| Asian | 0.6 (0.6-0.6) | 1.0 (1.0-1.1) | 1.2 (1.2-1.3) | 1.1 (1.0-1.1) | 1.1 (1.1-1.2) | 1.5 (1.4-1.5) | 1.9 (1.9-1.9) |

| Other | 0.84 (0.81-0.88) | 0.73 (0.70-0.76) | 0.77 (0.74-0.80) | 0.70 (0.67-0.73) | 0.89 (0.85-0.92) | 1.27 (1.24-1.31) | 1.46 (1.42-1.48) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0.12 (0.11-0.13) | 0.39 (0.37-0.41) | 0.45 (0.42-0.47) | 0.43 (0.40-0.45) | 0.50 (0.47-0.53) | 0.21 (0.20-0.23) | 0.22 (0.21-0.23) |

| Unknown | 0.36 (0.34-0.38) | 0.19 (0.17-0.20) | 0.13 (0.12-0.14) | 0.13 (0.12-0.15) | 0.27 (0.25-0.29) | 0.11 (0.10-0.12) | 0.25 (0.24-0.27) |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Based on a 20% random sample of the Medicare fee-for-service population.

Includes 100% of decedents with Medicare Advantage during the last 90 days of life.

The proportion of Medicare Advantage decedents increased from 22.6% (95% CI, 22.5%-22.7%; n = 358 600 of 1 586 081) in 2011 to 29.9% (95% CI, 29.9%-30.0%; n = 513 245 of 1 714 058) in 2015. Between 2000 and 2015, mean age and sex were similar in individuals enrolled in Medicare fee-for-service and Medicare Advantage. Black individuals were less likely to be enrolled in Medicare fee-for-service between 2011 and 2015, whereas enrollment in Medicare Advantage increased slightly among black individuals from 9.9% (95% CI, 9.8%-10.0%) to 10.6% (95% CI, 10.5%-10.7%).

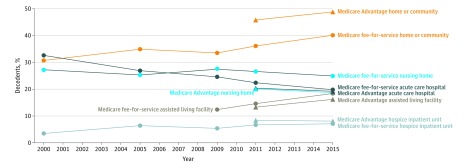

Change in Site of Death and Places of Care

From 2000 to 2015, the proportion of deaths that occurred in acute care hospitals and nursing homes continued to decrease (Figure and Table 2). Among Medicare fee-for-service decedents, there was a steady decrease in deaths in acute care hospitals from 32.6% (95% CI, 32.4%-32.8%) in 2000 to 19.8% (95% CI, 19.6%-20.0%) in 2015. Nursing homes as a site of death decreased by 2.3 percentage points from 27.2% (95% CI, 27.0%-27.3%) in 2000 to 24.9% (95% CI, 24.8%-25.1%) in 2015; however, nursing homes remained the site of death for 24.9% of Medicare fee-for-service decedents in 2015.

Figure. Patterns in Site of Death for Medicare Fee-for-Service and Medicare Advantage Decedents Between 2000 and 2015.

Site of death reported as an assisted living facility can only be reported when the service code captured that site of care. The denominators are reported in Table 2 with exception of the analyses of assisted living facilities. Data on assisted living facilities were only available for 2009, 2011, and 2015. The denominators for Medicare fee-for-service assisted living facilities includes persons who died while receiving hospice services and were as follows: n = 120 750 for 2009; n = 121 706 for 2011; and n = 126 510 for 2015. The denominators for Medicare Advantage assisted living facilities includes persons who died while receiving hospice services and were as follows: n = 186 810 for 2011 and n = 273 705 for 2015. Categories are not mutually exclusive because patients in the assisted living facility category may also be represented in the home or community category.

Table 2. Change in Site of Death, Place of Care, Health Care Transitions, and Potentially Burdensome Care Between 2000, 2005, 2009, 2011, and 2015.

| Decedents, % (95% CI)a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicare Fee-for-Serviceb | Medicare Advantagec | ||||||

| 2000 (n = 270 202) | 2005 (n = 291 819) | 2009 (n = 286 282) | 2011 (n = 262 338) | 2015 (n = 251 229) | 2011 (n = 358 600) | 2015 (n = 513 245) | |

| Place and Type of Care | |||||||

| Hospice services at the time of death | 21.6 (21.5-21.8) | 32.3 (32.1-32.4) | 42.2 (42.0-42.4) | 46.4 (46.2-46.6) | 50.4 (50.2-50.6) | 51.5 (51.1-51.7) | 52.6 (52.5-52.7) |

| Hospice services ≤3 d prior to death | 4.6 (4.5-4.7) | 7.6 (7.5-7.7) | 9.8 (9.7-10.0) | 7.5 (7.4-7.6) | 7.7 (7.6-7.8) | 7.9 (7.8-8.1) | 7.9 (7.8-7.9) |

| General inpatient hospice care during last 30 d of lifed | 3.9 (3.8-4.0) | 8.0 (7.9-8.1) | 11.3 (11.1-11.4) | 12.5 (12.3-12.6) | 12.4 (12.3-12.5) | 14.9 (14.8-15.0) | 13.8 (13.7-13.9) |

| Continuous home hospice care during last 30 d of lifee | 0.9 (0.9-1.0) | 2.3 (2.2-2.3) | 3.1 (3.0-3.1) | 3.4 (3.4-3.5) | 2.7 (2.6-2.7) | 4.6 (4.5-4.6) | 3.5 (3.5-3.6) |

| Hospitalization during last 30 d of life | 53.4 (53.2-53.6) | 57.3 (57.2-57.5) | 56.7 (56.5-56.8) | 54.3 (54.1-54.4) | 53.9 (53.7-54.1) | 44.8 (44.7-45.0) | 44.6 (44.4-44.7) |

| Hospitalization during last 90 d of life | 62.9 (62.7-63.0) | 70.1 (70.0-70.3) | 69.3 (69.2-69.6) | 65.6 (65.4-65.8) | 65.2 (65.1-65.5) | 55.1 (54.9-55.2) | 56.5 (56.4-56.6) |

| ICU use during last 30 d of life | 24.3 (24.1-24.4) | 26.3 (26.1-26.5) | 29.2 (29.0-29.3) | 29.1 (28.9-29.3) | 29.0 (28.8-29.2) | 26.6 (26.5-26.8) | 27.4 (27.3-27.5) |

| Nursing home stay during the last 90 d of life | 42.8 (42.6-43.0) | 42.2 (42.0-42.4) | 45.0 (44.8-45.2) | 46.0 (45.8-46.1) | 43.5 (43.2-43.6) | 37.7 (37.5-37.8) | 33.2 (33.1-33.3) |

| Type of Health Care Transition and Potentially Burdensome Care | |||||||

| Health care transition during last 3 d of life | 10.3 (10.1-10.4) | 12.4 (12.3-12.5) | 14.2 (14.0-14.3) | 11.2 (11.1-11.3) | 10.8 (10.6-10.9) | 10.0 (9.9-10.1) | 9.4 (9.3-9.4) |

| ≥3 Hospitalizations during last 90 d of life | 10.3 (10.2-10.4) | 10.9 (10.8-11.0) | 11.5 (11.4-11.6) | 6.9 (6.8-7.0) | 7.1 (7.0-7.2) | 5.8 (5.7-5.9) | 6.1 (6.1-6.2) |

| Multiple hospitalizations for infections or dehydration during last 120 d of life | 14.6 (14.4-14.7) | 16.0 (15.8-16.1) | 16.7 (16.6-16.9) | 11.7 (11.5-11.8) | 12.2 (12.1-12.3) | 9.6 (9.5-9.7) | 10.5 (10.4-10.6) |

| Mechanical ventilation ≥4 d during terminal hospitalization | 3.1 (3.1-3.2) | 3.3 (3.2-3.4) | 3.2 (3.1-3.3) | 3.2 (3.1-3.3) | 2.5 (2.4-2.5) | 3.3 (3.3-3.4) | 2.7 (2.7-2.8) |

| No. of transitions per decedent between nursing home and hospital during last 90 d of life | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.49 (1.0) | 0.56 (1.2) | 0.58 (1.2) | 0.36 (0.70) | 0.33 (0.67) | 0.23 (0.55) | 0.21 (0.52) |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0-1.0) | 0 (0-1.0) | 0 (0-1.0) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range.

Unless otherwise indicated.

Based on a 20% random sample of the Medicare fee-for-service population.

Includes 100% of decedents with Medicare Advantage during the last 90 days of life.

Short-term management of pain or other symptoms provided in a free-standing hospice inpatient unit, an acute care hospital, or in a nursing home.

Similar hospice services as those listed in footnote “d” but these services were provided in a home or in a nursing home that does not have skilled nursing facility beds.

The previously reported pattern of persons dying while receiving hospice services continued, increasing from 21.6% (95% CI, 21.5%-21.8%) in 2000 to 50.4% (95% CI, 50.2%-50.6%) in 2015 among Medicare fee-for-service decedents. Conversely, the proportion of decedents using hospice services for 3 days or less decreased from 9.8% (95% CI, 9.7%-10.0%) in 2009 to 7.7% (95% CI, 7.6%-7.8%) in 2015. General inpatient hospice care during the last 30 days of life increased slightly between 2000 and 2015. Continuous home hospice care during the last 30 days of life decreased from 3.4% (95% CI, 3.4%-3.5%) in 2011 to 2.7% (95% CI, 2.6%-2.7%) in 2015. Between 2000 and 2015, more deaths occurred in freestanding hospice inpatient units and in the home or community setting. Of these late hospice referrals, 40.3% (95% CI, 39.7%-40.8%) were preceded by hospitalization with an ICU stay. In 2015, among those with a late hospice referral, 42.9% were in an ICU (95% CI, 41.2%-43.6%).

Among those persons who received hospice services and were classified as dying in the home or in the community setting in 2015, 18.4% (95% CI, 18.1%-18.6%) of Medicare fee-for-service patients were living in an assisted living facility at the time of death. Among Medicare fee-for-service decedents, ICU use during the last 30 days of life increased from 24.3% (95% CI, 24.1%-24.4%) in 2000 to 29.2% (95% CI, 29.0%-29.3%) in 2009. This increase in ICU use among Medicare fee-for-service decedents during the last 30 days of life stabilized between 2009 and 2015 at 29.0% (95% CI, 28.8%-29.2%). Hospitalizations during the last 90 days of life increased until 2009 then decreased by 2.8 percentage points from 69.3% (95% CI, 69.2%-69.6%) in 2009 to 65.2% (95% CI, 65.1%-65.5%) in 2015. Nursing home stays remained relatively unchanged; there were 43.5% (95% CI, 43.2%-43.6%) of Medicare fee-for-service decedents who stayed in a nursing home during the last 90 days of life in 2015.

Health Care Transitions and Potentially Burdensome Care

Health care transitions between a nursing home and hospital increased from 2000 to 2009, then decreased from a mean of 0.58 transitions (interquartile range, 0-1.0) per Medicare fee-for-service decedent in 2009 to 0.33 transitions (interquartile range, 0-0) per decedent in 2015. A similar pattern was seen among Medicare fee-for-service decedents during the last 3 days of life; health care transitions increased from 10.3% (95% CI, 10.1%-10.4%) in 2000 to 14.2% (95% CI, 14.0%-14.3%) in 2009 and then decreased to 10.8% (95% CI, 10.6%-10.9%) in 2015. Multiple hospitalizations (≥3) during the last 90 days of life declined from 11.5% (95% CI, 11.4%-11.6%) in 2009 to 7.1% (95% CI, 7.0%-7.2%) in 2015. Spending 4 or more days receiving mechanical ventilation during terminal hospitalization decreased slightly (Table 2).

Patterns of Care Among Medicare Advantage vs Medicare Fee-for-Service in 2011 and 2015

The Figure and the last 4 columns of Table 2 contrast Medicare fee-for-service and Medicare Advantage decedents in 2011 and 2015. The likelihood of death in an acute care hospital was similar among Medicare fee-for-service and Medicare Advantage decedents in 2015. However, Medicare Advantage decedents were less likely to die in a nursing home and more likely to die at home or in a community setting.

More Medicare Advantage decedents (ie, difference of 2.2%) received hospice services in 2015. Medicare Advantage decedents were less likely to be hospitalized and there were differences in the rates of hospitalizations during the last 30 and 90 days of life. For the last 30 days of life, the difference in the hospitalization rates was 9.3%.

Discussion

Comparing Medicare fee-for-service decedents from 2000 to 2015, there was a lower likelihood of death in an acute care hospital, the rate of ICU use during the last month of life increased from 2000 to 2009 and then stabilized from 2009 to 2015, and rates of health care transitions and burdensome care increased from 2000 to 2009 and then declined from 2009 to 2015. This study also reports on the end-of-life experience of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage, which is important given the continued growth of this program. A similar pattern of decrease in deaths in an acute care hospital was observed, but Medicare Advantage decedents were less likely to be hospitalized, less likely to die in a nursing home, and more likely to die in the community.

These results are consistent with a prior study of the Healthcare Effectiveness and Data Information Set.19 It is difficult to attribute the observed changes to any single intervention or policy designed to improve care at the end of life. Beginning prior to enactment of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, there has been a reduction in potentially burdensome health care transitions and terminal hospitalizations, but little change in ICU use during the last 30 days of life.

Between 2009 and 2015, a reduction in health care transitions occurred. Based on previous research linking families’ perceptions of the quality of decedents’ care, transitions between health care institutions during the last 3 days of life, and multiple hospitalizations for infections or dehydration during the last 120 days of life were considered potentially burdensome. Health care transitions during the last 3 days of life, even when patients are to receive hospice services,20 are associated with lower ratings of the quality of care among persons with advanced cancer.

An analysis of the National Health and Aging Trends study found that individuals aged 65 years or older who experienced health care transitions during the last 3 days of life were associated with higher levels of concerns about the quality of care, more unmet needs, and lower ratings regarding the quality of care.20,21 Experiencing multiple hospitalizations for infections such as urinary tract infection, pneumonia, septicemia, or dehydration was associated with a median survival of less than 6 months among nursing home residents with advanced dementia.22 Both of these types of transitions declined between 2009 and 2015.

Use of ICU services during the last 30 days of life increased from 2000 to 2009, but remained unchanged at approximately 29.0% from 2009 to in 2015. The National Academy of Medicine’s 2015 report on dying in America2 defined a good death as “One that is free from avoidable distress and suffering for patients, families, and caregivers; in general accord with patients’ and families’ wishes; and reasonably consistent with clinical, cultural, and ethical standards.” Death in the ICU is seldom viewed as a good death.

Important concerns have been expressed about the use of ICU services at the end of life; the types of concerns include inadequate communication,23 poorly treated symptoms,24 psychological outcomes of next of kin,25,26 and bereaved family members’ concerns that the medical care provided was not consistent with the decedent’s preferences.27 Even though individuals may differ in their preferences regarding location of death, the ongoing trend toward stabilization of ICU use is an important marker of improvement.

Multiple efforts between 2000 and 2015 attempted to improve care at the close of life. It is difficult to disentangle efforts such as public education, promotion of advance directives through the Patient Self-Determination Act, increased access to hospice and palliative care services, financial incentives of payment policies, and other secular changes. As reported in Table 2, potentially burdensome health care transitions decreased between 2009 and 2011. In 2009, the CMS started publicly reporting 30-day hospital readmission rates in February and debate of the Affordable Care Act by Congress started in March.

During the early 1990s, the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments3 implemented a multifaceted intervention that failed to improve care of seriously ill patients. A potential reason for this failure is the need for multifaceted interventions that additionally address economic incentives that contribute to care fragmentation and overuse.28 The public reporting of 30-day hospital readmission rates and payment penalties for risk-adjusted readmission rates potentially provide an opportunity to improve more timely access to and effectiveness of palliative care and hospice services.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the finding that the proportion of deaths that occurred in the community increased among Medicare fee-for-service decedents should be interpreted with caution. This research relied on Medicare billing data and Minimum Data Set assessments to determine the site of death based on the place of service recorded on the submitted claims. Medicare billing data do not differentiate community deaths that are in a personal home, in an assisted living facility, or at foster care home except for decedents who died while receiving hospice services.

However, with the finding that 50.4% of Medicare fee-for-service decedents died while receiving hospice services in 2015, it is likely that some of this shift is based on persons dying in assisted living facilities. Compared with dying at home, the research on the quality of dying in an assisted living facility found improvement in dyspnea but with a higher rate of pain.29 Research is needed to examine whether death in an assisted living facility is similar to the experience of death in a nursing home or in a private home while receiving hospice services.

Second, this study was restricted to Medicare beneficiaries so the findings may not generalize to other populations. Third, information on patient preferences was not present in administrative data; therefore, this study was unable to determine whether reported outcomes are consistent with a patient’s informed choice.

Fourth, although this study addressed a limitation of the 2000-2009 study1 by including the inpatient billing data from Medicare Advantage patients that is used by the CMS in the determination of disproportionate share and medical education adjustments for hospitals, these claims data were not available for a small percentage of hospitals (hospitals that only provide care for Medicare Advantage patients and critical access hospitals).

Fifth, there are no published estimates of the accuracy of these informational claims. Sixth, an analysis was not possible for outcomes by income or cause of death because these data were not available in the administrative data.

Conclusions

Among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who died in 2015 compared with 2000, there was a lower likelihood of dying in an acute care hospital, an increase and then stabilization of intensive care unit use during the last month of life, and an increase and then decline in health care transitions during the last 3 days of life.

Section Editor: Derek C. Angus, MD, MPH, Associate Editor, JAMA (angusdc@upmc.edu).

References

- 1.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, et al. . Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA. 2013;309(5):470-477. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.207624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.SUPPORT Principal Investigators A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients: the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA. 1995;274(20):1591-1598. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530200027032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. . Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291(1):88-93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teno JM, Mor V, Ward N, et al. . Bereaved family member perceptions of quality of end-of-life care in US regions with high and low usage of intensive care unit care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(11):1905-1911. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53563.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumenthal D, Abrams MK. Tailoring complex care management for high-need, high-cost patients. JAMA. 2016;316(16):1657-1658. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aldridge MD, Kelley AS. The myth regarding the high cost of end-of-life care. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):2411-2415. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevenson DG, Dalton JB, Grabowski DC, Huskamp HA. Nearly half of all Medicare hospice enrollees received care from agencies owned by regional or national chains. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(1):30-38. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumanovsky T, Augustin R, Rogers M, Lettang K, Meier DE, Morrison RS. The growth of palliative care in US hospitals: a status report. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(1):8-15. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wachter RM, Goldman L. The hospitalist movement 5 years later. JAMA. 2002;287(4):487-494. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.4.487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Research Data Assistance Center Medicare managed care enrollees and the Medicare utilization files. https://www.resdac.org/resconnect/articles/1142011. Accessed February 18, 2018.

- 12.Huckfeldt PJ, Escarce JJ, Rabideau B, Karaca-Mandic P, Sood N. Less intense postacute care, better outcomes for enrollees in Medicare Advantage than those in fee-for-service. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(1):91-100. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Intrator O, Hiris J, Berg K, Miller SC, Mor V. The Residential History File: studying nursing home residents’ long-term care histories(*). Health Serv Res. 2011;46(1 pt 1):120-137. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01194.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Welch LC, Teno JM, Mor V. End-of-life care in black and white: race matters for medical care of dying patients and their families. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1145-1153. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53357.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnato AE, Alexander SL, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC. Racial variation in the incidence, care, and outcomes of severe sepsis: analysis of population, patient, and hospital characteristics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(3):279-284. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-480OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koroukian SM, Schiltz NK, Warner DF, et al. . Social determinants, multimorbidity, and patterns of end-of-life care in older adults dying from cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017;8(2):117-124. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2016.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enguidanos S, Yip J, Wilber K. Ethnic variation in site of death of older adults dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(8):1411-1416. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53410.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatala M, Sloane RJ, Tanis D, Galanos AN, Tulsky JA. Ethnic differences in the place of death of elderly hospice enrollees. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2209-2215. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00502.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevenson DG, Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Newhouse JP, Landon BE. Service use at the end-of-life in Medicare advantage versus traditional Medicare. Med Care. 2013;51(10):931-937. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a50278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. . Family perspectives on aggressive cancer care near the end of life. JAMA. 2016;315(3):284-292. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makaroun LK, Teno JM, Freedman VA, Kasper JD, Gozalo P, Mor V. Late transitions and bereaved family member perceptions of quality of end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teno JM, Gozalo P, Mitchell SL, Tyler D, Mor V. Survival after multiple hospitalizations for infections and dehydration in nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2013;310(3):319-320. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.8392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Norris K, Asp C, Byock I. A measure of the quality of dying and death: initial validation using after-death interviews with family members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(1):17-31. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00419-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mularski RA, Heine CE, Osborne ML, Ganzini L, Curtis JR. Quality of dying in the ICU: ratings by family members. Chest. 2005;128(1):280-287. doi: 10.1016/S0012-3692(15)37958-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, Matulonis UA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. Place of death: correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers’ mental health. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(29):4457-4464. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodríguez Villar S, Sánchez Casado M, Prigerson HG, et al. . Prolonged grief disorder in the next of kin of adult patients who die during or after admission to intensive care. Chest. 2012;141(6):1635-1636. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-3099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khandelwal N, Curtis JR, Freedman VA, et al. . How often is end-of-life care in the United States inconsistent with patients’ goals of care? J Palliat Med. 2017;20(12):1400-1404. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tolle SW, Teno JM. Lessons from Oregon in embracing complexity in end-of-life care. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(11):1078-1082. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1612511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cartwright JC. Nursing homes and assisted living facilities as places for dying. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2002;20:231-264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]