Abstract

Objective

To assess quality of life (QOL) in women who experienced a severe maternal morbidity (SMM) event and associated factors, in comparison to those who did not.

Study Design

Retrospective cohort study performed at the maternity of the University of Campinas in Brazil, including 801 women with or without SMM, within 6 months to 5 years after delivery. Women were interviewed by phone and data were electronically stored, using the Brazilian version of the SF36 to assess women's self-perception of quality of life. To analyze a possible relationship between SMM and perceived impairment in quality of life, χ2 and Fisher's Exact tests were used. Multiple analysis using Generalized Linear Models was applied to identify factors independently associated with the general health score. The main outcome measures were general and domain-specific SF36 scores on quality of life.

Results

Maternal morbidity conditions were associated with lower scores of patient perceptions of quality of life in the following domains: physical functioning, role-limiting physical, pain, and general health status. A lower level of school education, not having a partner, caesarean section, and history of previous clinical conditions were associated with a worse perception of general health and quality of life.

Conclusion

Health professionals should know the association between life conditions, previous chronic health conditions, and SMM for women during prenatal care to beyond 42 weeks postpartum. Longitudinal and interdisciplinary actions should be put into practice to provide healthcare for these women, with special emphasis on the effective reduction in health inequities.

1. Introduction

Recently, there has been a considerable reduction in maternal mortality in Brazil. However, this decrease was not sufficient to reach the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) in 2015. The reduction in maternal deaths is partly explained by more well qualified obstetric care for women in maternity hospitals and emergency facilities [1]. Surviving a potentially life-threatening condition during or after pregnancy and/or childbirth, along with maternal mortality, should also be considered an indicator of quality of obstetric care. Nevertheless, several health and life aspects of these surviving women are still unknown. A follow-up of these women may be required. This is a challenging task, since little is known about the long-term repercussions of complications on the lives of postpartum women [2, 3]. Such knowledge may improve healthcare and prevent further damage to women experiencing such a condition [4]. Ignoring possible long-term repercussions after exposure to a life-threatening condition may hinder the desirable convergence between a reduction in maternal deaths and a decrease in severe pregnancy-related complications [5].

The combination of pregnancy and severe life-threatening complications may trigger intense physical and psychological distress, which can culminate in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), among other adverse consequences for these women [6, 7]. Survivors of obstetric complications are more physically and socially vulnerable. These women are more prone to develop postpartum mental issues, such as postpartum depression, anxiety, and sexual disorders [8–11]. Six months after delivery, women who experienced severe bleeding, severe preeclampsia (including HELLP syndrome), sepsis, or uterine rupture had a worse evaluation of their own overall health status [9].

Adverse consequences are not limited to the postpartum period. Women who particularly suffered from severe maternal morbidity may have long-term negative consequences after experiencing such episodes. Consequences may affect specially women who underwent operative delivery [12, 13]. Some authors reported that survivors of life-threatening conditions have described their fear of death, loss of hope, concerns about possible upcoming surgical procedures, memory lapses, mourning for the loss of their babies or their reproductive capacity after hysterectomy, feelings of loss of female identity, among others [5, 14]. Therefore, it is necessary to comprehensively understand how severe maternal morbidity influences women's global perception of their quality of life (QOL) after such events. The main purpose of this study was to assess the occurrence and factors associated with the perception of impaired quality of life among women who experienced a severe maternal morbidity event, in comparison to those who did not.

2. Methods

This study is part of the cohort study “Multidimensional assessment of the impact of severe maternal morbidity on women's health and life”, carried out at the maternity hospital of the University of Campinas in Brazil [2, 15]. Severe Maternal Morbidity episodes were considered as exposure for women discharged from the ICU. Women who had been exposed to those events were included in the “SMM group”, following the WHO concept and criteria [16]. The nonexposed group comprised women who had a low-risk term delivery at the same facility. These women had given birth to live, healthy children after 37 weeks of gestation or more. Each control was randomly selected according to time of delivery that was close to the year of delivery of each SMM case, in order to keep a balance of time of delivery between groups. The recruitment period ranged from January 1st, 2008, to December 31st, 2012.

Data were collected from June 2012 to July 2013, including women who had delivered at least 6 months before the first interview. The period between the first interview and childbirth ranged from 6 months to 5 years; however it was determined to be similar in both groups and was considered in the analysis. Sample size for evaluation of quality of life was defined from previous studies [17, 18]. Accordingly, 50% of women had serious physical and emotional problems during the first year after delivery. Assuming an absolute difference of 11% between both groups, with a type I error of 5% and a type II error of 10%, each group would require 337 women, in a total of 674.

From ICU and hospital records, 1,157 women matched selection criteria for both groups. Of the total number, 840 women were successfully traced by phone. Women were then invited to participate in the study. Those who agreed were immediately interviewed by telephone after recording their consent, or another phone call was made to carry out the interview. Aspects evaluated at that time were perception of health-related quality of life through the SF36 questionnaire, and posttraumatic stress disorder and further information on both reproductive and general health were obtained from medical charts.

Quality of life was assessed through the Brazilian version of the Medical Outcomes Study 36–Item Short-Form Health Survey, the SF36 [19, 20]. The questionnaire was applied at one point in time during a telephone interview by trained interviewers and the mean time for telephone interview was 15 minutes. Two interviewers were trained for interviews using tele-research and five were trained for face-to-face interview. The training was carried out by researchers with expertise in tele-research. There were two days of training with practical activities of telephone interview and face-to-face interview. Questions and answers fed an online questionnaire, which was also digitally recorded. This procedure is described as Computer-Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI), a feasible tool to obtain health information [21], including research on quality of life using the SF36 [22]. A research supervisor listened to a random sample of around 5% of recorded interviews to check for consistency of information stored in the digital database, in an attempt to promote healthcare quality.

The SF36 is a generic instrument for multidimensional evaluation of quality of life developed from the Medical Outcomes Study [23]. It was validated for the Portuguese language and the instrument has already been applied at some Brazilian studies [19, 24, 25]. The questionnaire has also been used for general evaluation of health-related quality of life in women within 6 to 12 months after severe maternal morbidity events [9, 26–30]. No other instrument was used for evaluating the quality of life, only the SF-36 as originally planned [2]. In fact, there is no other specific instrument for pregnancy already available. WHO is now doing an effort to reach such an instrument that could be used for this purpose during and after pregnancy, but it is not yet available. We supported our choice in other studies that used the SF-36 with women during pregnancy, who experienced obstetric and postpartum complications [9, 26–30].

The questionnaire is easily applied and contains 36 items divided into eight domains. Two summarized components (physical health and mental health) are derived from these 8 domains. Domains of functional capacity (domain 1), physical aspects (domain 2), and pain (domain 3) are correlated with the physical component. Domains of general health status (domain 4), vitality (domain 5), and social aspects (domain 6) are correlated with physical and mental components. Finally, emotional aspects (domain 7) and mental health (domain 8) are correlated with the mental component [20]. The domain responses are summed to form a score. Higher scores represent a better health status. There is no normal pattern result or cut-off point for the total score. A comparative analysis between two or more groups should thus always be made. The final score ranges from 0 to 100. The latter score corresponds to the best perception of quality of life.

Data were collected using an online platform (Lime Survey®) and analyzed with SPSS® version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). After completion of data collection, an intense and detailed process of data management for consistency checking was performed, following a routine planned to explore the relationships between several variables recorded. Inconsistencies were corrected whenever identified, using the original forms, clinical records, or recorded interviews or even by phoning women again to ask them about any missing data. For statistical analysis, initially sociodemographic characteristics and information from pregnancy and childbirth were compared between groups of women with or without SMM using Pearson's Chi-square and Fisher's Exact tests. The median and mean values (±SD) of each SF36 domain scores for participants in both groups were assessed using Student's t-test. In domain 4 related to general health status, the mean scores were estimated for categories of each maternal or delivery characteristic, using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. Finally, multiple regression analysis was performed using a Generalized Linear Model to identify variables independently associated with general health scores, controlled by predictor variables significantly associated with the outcome. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (letter of approval CEP 233/2009). All participants recorded an audio consent form and/or signed a written version of the consent.

3. Results

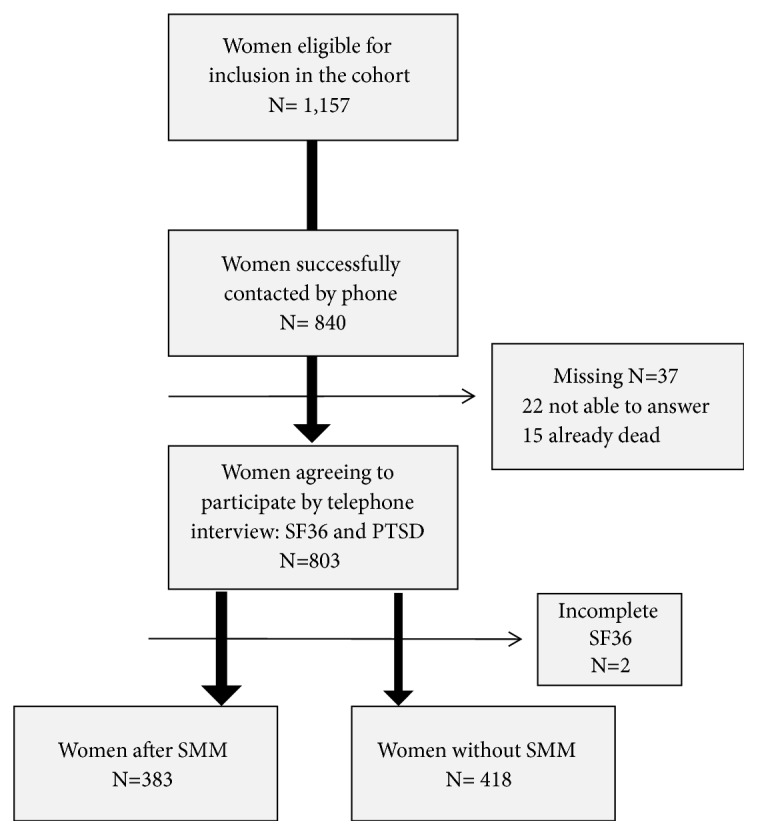

A total of 1,157 women were eligible for the study. Of the total sum, 840 women were traced by phone. However, 37 of these women failed to be interviewed and then 803 answered the SF36 questionnaire. Two of these women did not complete the questionnaire due to personal reasons (a 72.60% trace rate and a 69.23% response rate). Of the total of women who completed the questionnaire, 383 women experienced an SMM episode and were considered exposed patients, while 418 had uncomplicated pregnancies. Among the 37 missing cases, 22 women had been unable to answer the questionnaire for whatever reason and 15 had died (9 from late maternal causes) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of women in the study.

There were significant differences between groups regarding age, mode of delivery, and mainly previous exposure to pathological conditions and smoking (Table 1). Women who had SMM conditions were mostly over 30 years of age, had undergone caesarean section, and had clinical complications, such as hypertensive disorders, obesity, and cardiac disease (65%). Besides higher maternal age, no other life style factors were identified as associated with severe maternal morbidity.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of women with and without previous condition of Severe Maternal Morbidity (PLTC+MNM).

| Characteristics | SMM Group | Group Without Morbidity | p-value ∗ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Age (years) a | 0.003 | ||||

| <20 | 16 | 4.2 | 24 | 5.8 | |

| 20 -24 | 58 | 15.2 | 81 | 19.4 | |

| 25-29 | 86 | 22.5 | 110 | 26.4 | |

| 30-34 | 87 | 22.8 | 111 | 26.6 | |

| 35-39 | 82 | 21.5 | 56 | 13.4 | |

| ≥40 | 53 | 13.9 | 35 | 8.4 | |

| Parity b | 0.307 | ||||

| ≤1 | 98 | 31.7 | 110 | 33.7 | |

| 2 | 93 | 30.1 | 103 | 31.6 | |

| 3 | 55 | 17.8 | 65 | 19.9 | |

| ≥4 | 63 | 20.4 | 48 | 14.7 | |

| Skin color/Ethnicity c | 0.183 | ||||

| Caucasian | 199 | 52.1 | 197 | 47.1 | |

| Non Caucasian | 183 | 47.9 | 221 | 52.9 | |

| Schooling d | 0.257 | ||||

| Up to 4 years | 24 | 6.7 | 16 | 4.1 | |

| 5 to 8 years | 105 | 29.3 | 104 | 26.5 | |

| 9 to 11 years (high) | 194 | 54.2 | 235 | 59.9 | |

| ≥12 years (University) | 35 | 9.8 | 37 | 9.4 | |

| Marital status e | 0.955 | ||||

| With partner | 260 | 82.5 | 269 | 83.3 | |

| Without partner | 55 | 17.5 | 54 | 16.7 | |

| Time elapsed between delivery and interview | 0.429 | ||||

| 1-2 years | 154 | 40.3 | 180 | 43.1 | |

| 3-5 years | 229 | 59.7 | 238 | 56.9 | |

| Mode of delivery e | <0.001 | ||||

| Vaginal delivery | 67 | 17.9 | 217 | 51.9 | |

| Caesarean section | 307 | 82.1 | 201 | 48.1 | |

| Gender of the child ∗∗f | 0.274 | ||||

| Male | 204 | 55.7 | 214 | 51.6 | |

| Female | 162 | 44.3 | 201 | 48.4 | |

| Neonatal outcome ∗∗g | 0.083 | ||||

| Alive | 300 | 95.8 | 399 | 98.3 | |

| Neonatal death | 13 | 4.2 | 7 | 1.7 | |

| Previous maternal condition e | 245 | 65.2 | 137 | 33.1 | <0.001 |

| Hypertensive disorders c | 93 | 24.3 | 26 | 6.2 | <0.001 |

| Obesity c | 77 | 20.2 | 52 | 12.4 | 0.004 |

| Diabetes c | 24 | 6.3 | 9 | 2.2 | 0.006 |

| Smoking c | 29 | 7.6 | 12 | 2.9 | 0.004 |

| Cardiac Disease c | 19 | 5.0 | 4 | 1.0 | 0.001 |

| Respiratory Disease c | 19 | 5.0 | 5 | 1.2 | 0.003 |

| Renal Disease c | 15 | 3.9 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.002 |

| Sickle cell/thalassemia c | 9 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | 0.001 |

| HIV c | 1 | 0.3 | 5 | 1.2 | 0.220 |

| Thyroid disease c | 26 | 6.8 | 8 | 1.9 | 0.001 |

| Neurological disease c | 16 | 4.2 | 4 | 1.0 | 0.007 |

| Collagenoses c | 7 | 1.8 | 5 | 1.2 | 0.654 |

| Neoplasia c | 5 | 1.3 | 4 | 1.0 | 0.744 |

| Others | |||||

| Total | 383 | 418 | |||

MNM: maternal near miss; PLTC: potentially life-threatening condition.

Missing information for a:2; b: 166; c:1; d:51; e: 9; f: 20; g: 82; e:170; e:11 cases.

∗p value derived from Pearson Chi-square or Fisher Exact tests.

∗∗Only for pregnancies resulting delivery.

Table 2 shows median and mean SF36 domain scores, according to maternal morbidity. There were significant differences between groups in domain 1 (physical functioning), domain 2 (role-limiting physical), domain 3 (pain), and domain 4 (general health). The mean score in general health domain was 67.2 for women without morbidity, while it was 59.0 for those with severe maternal morbidity. Mean scores in the general health domain were significantly higher in women who had a higher level of school education, had a life partner, and delivered by the vaginal route for the index pregnancy (Table 3). There were no differences between both groups in terms of age, parity, ethnicity, infant gender, or outcome. There was no difference in the SF-36 scores according the time since delivery.

Table 2.

Median and mean values for SF36 domain scores for groups with and without severe maternal morbidity (means with SD).

| SF-36 Domains | SMM Group | Group Without Morbidity | p-value ∗ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Med | Mean | SD | N | Med | Mean | SD | N | ||

| Domain 1: | |||||||||

| Physical functioning | 80 | 75.17 | 22.38 | 381 | 90 | 83.02 | 18.26 | 415 | <0.001 |

| Domain 2: | |||||||||

| Role-limiting physical | 100 | 65.64 | 40.77 | 382 | 100 | 77.22 | 35.48 | 417 | <0.001 |

| Domain 3: | |||||||||

| Pain | 61 | 59.52 | 24.90 | 381 | 62 | 63.36 | 22.97 | 415 | 0.018 |

| Domain 4: | |||||||||

| General health | 57 | 59.05 | 21.07 | 376 | 67 | 67.24 | 19.63 | 409 | <0.001 |

| Domain 5: | |||||||||

| Vitality | 55 | 51.81 | 21.68 | 381 | 55 | 54.52 | 21.25 | 411 | 0.110 |

| Domain 6: | |||||||||

| Social functioning | 75 | 67.04 | 27.28 | 380 | 75 | 70.79 | 25.69 | 410 | 0.063 |

| Domain 7: | |||||||||

| Role-limiting emotional | 75 | 58.90 | 44.47 | 382 | 100 | 63.61 | 43.01 | 417 | 0.127 |

| Domain 8: | |||||||||

| Mental Health | 56 | 56.16 | 21.91 | 382 | 60 | 58.41 | 22.92 | 410 | 0.108 |

MNM: maternal near miss; PLTC: potentially life-threatening condition.

∗Student's t-test.

Table 3.

Mean values of SF36 fourth domain scores (general health) according to some maternal and delivery characteristics.

| Characteristics | Mean | SD | n | p-value ∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (y) a | 0.239 | ||||

| ≤ 19 | 57.50 | 17.01 | 40 | ||

| 20-29 | 63.34 | 20,69 | 333 | ||

| 30-39 | 64.17 | 21.31 | 330 | ||

| ≥ 40 | 62.76 | 19.95 | 83 | ||

| Number of pregnancies b | 0.394 | ||||

| 1 | 63.09 | 20.81 | 204 | ||

| ≥ 2 | 61.53 | 20.94 | 420 | ||

| Schooling (years) c | 0.001 | ||||

| Up to 8 | 59.38 | 20.87 | 242 | ||

| Above 8 | 64.61 | 20.61 | 496 | ||

| Ethnicity a | 0.356 | ||||

| White | 63.99 | 20.98 | 388 | ||

| Nonwhite | 62.69 | 20.47 | 398 | ||

| Marital status d | 0.013 | ||||

| Without a partner | 57.81 | 19.77 | 103 | ||

| With a partner | 62.85 | 20.98 | 519 | ||

| Time since delivery (y) a | 0.398 | ||||

| < 1 | 61.26 | 19.76 | 111 | ||

| 1 - <2 | 63.57 | 20.95 | 274 | ||

| 2 - ≥3 | 63.74 | 20.84 | 401 | ||

| Route of delivery e | <0.001 | ||||

| Vaginal | 67.89 | 20.46 | 278 | ||

| Cesarean section | 60.85 | 20.49 | 499 | ||

| Child outcome f | 0.308 | ||||

| Alive | 63.55 | 20.91 | 685 | ||

| Neonatal death | 59.20 | 19.81 | 20 | ||

| Sex of the child g | 0.440 | ||||

| Male | 64.03 | 20.67 | 408 | ||

| Female | 62.64 | 21.09 | 358 | ||

| Any morbid condition h | 57.68 | 20.76 | 374 | <0.001 | |

| Hypertensive disorders i | 52.39 | 19.56 | 116 | <0.001 | |

| Obesity i | 58.83 | 21.26 | 126 | 0.008 | |

| Diabetes i | 47.84 | 19.21 | 32 | <0.001 | |

| Smoking i | 60.00 | 18.84 | 40 | 0.300 | |

| Cardiac Disease i | 55.09 | 18.87 | 23 | 0.076 | |

| Respiratory Disease i | 48.52 | 20.47 | 23 | 0.001 | |

| Renal Disease i | 57.06 | 22.73 | 16 | 0.235 | |

| Sickle cell/thalassemia i | 57.22 | 26.52 | 9 | 0.538 | |

| HIV/AIDS i | 45.50 | 18.44 | 6 | 0.040 | |

| Thyroid disease i | 55.79 | 21.97 | 33 | 0.052 | |

| Neurological disease i | 61.10 | 21.92 | 20 | 0.628 | |

| Collagenoses i | 55.67 | 22.08 | 12 | 0.200 | |

| Neoplasia i | 61.50 | 30.18 | 8 | 0.867 | |

∗Nonparametric test: Mann-Whitney.

Missing information for a: 15 cases; b: 177; c: 63; d: 179; e: 24; f: 96; g:35; h: 26; i:16 cases.

Values in bold mean that they are statistically significant (p<0.05).

Multiple regression analysis showed that SMM alone was not independently associated with perceived quality of life (Table 4). On the other hand, increasing maternal ages, delivery by the vaginal route, and higher schooling were independently associated with higher general health scores, while having hypertension or some previous clinical conditions (respiratory diseases, thyroid disorders, or HIV) correlated with lower general health status scores.

Table 4.

Variables independently associated with mean of general health perception score, domain 4, by multiple regression analysis (Generalized Linear Model) [n=571].

| Variable | Coeff. | SE coeff. | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | -0.251 | 0.046 | <0.001 |

| Mode of delivery (Vaginal) | 0.109 | 0.030 | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Respiratory diseases | -0.234 | 0.086 | 0.007 |

| Schooling (>8 years) | 0.082 | 0.031 | 0.009 |

| Thyroid diseases | -0.182 | 0.074 | 0.014 |

| HIV/AIDS | -0.378 | 0.170 | 0.026 |

| Constant | 3.861 | 0.076 | <0.001 |

Coeff.: estimated coefficient; SE coeff.: standard error of estimated coefficient; p: p value.

Independent variables initially considered: group (PLTC, MNM: 1/ Control: 0); age (years); parity (1: 0/ ≥2: 1); skin color/ ethnicity (Caucasian: 0/ Non-Caucasian: 1); schooling (up to 8 years: 0/ >8 years: 1); marital status (without partner: 1/ with partner: 0); time elapsed between delivery and interview (1-2 years: 0/ 3-5: 1); mode of delivery (vaginal: 1/ cesarean: 0); gender of the child (male: 0/ female: 1); Neonatal outcome (alive: 1/ death: 0); previous maternal pathology: hypertension (yes: 1/ no: 0); obesity (yes: 1/ no: 0); diabetes (yes: 1/ no: 0); smoking (yes: 1/ no: 0); cardiac diseases (yes: 1/ no: 0); respiratory diseases (yes: 1/ no: 0); renal diseases (yes: 1/ no: 0); sickle cell/thalassemia (yes: 1/ no: 0); HIV/AIDS (yes: 1/ No: 0); thyroid diseases (yes: 1/ no: 0); neurological diseases (yes: 1/ no: 0); collagenoses (yes: 1/ no: 0); neoplasia (yes: 1/ no: 0).

4. Discussion

Quality of life assessment after childbirth showed that women with SMM episodes were older, underwent more caesarean sections, had more morbid conditions prior to pregnancy, and had significantly lower mean scores in SF36 domains 1 to 4, most specifically related to physical aspects and general health, than women without maternal complications. These scores were lower in women with less school education, no partner, who had caesarean section, and with any previous morbid conditions. Conditions that were independently associated with a low score in SF36 domain 4 were hypertension, caesarean delivery, maternal age, respiratory disease, low schooling, and other previous morbid conditions.

This study has some limitations. It was retrospective with SF36 instrument administered only once during postpartum period. Therefore, general health perception before interview was unknown and the time between index pregnancy and interview may have generated recall biases. The SF36 is a generic assessment without clinical aspects and possible risk factors and thus unable to provide a concrete measure of health outcome [20]. Complementary methods using standardized or specific tools, combined with qualitative analyses, are options worthy of exploring. However, the results allow comparisons of QOL scores in women exposed and nonexposed to SMM.

These results are in agreement with other studies investigating what happens to women surviving severe situations during pregnancy, childbirth, or postpartum period [9, 10, 12, 26, 31]. Concern about QOL assessment in women after a SMM event reflects a trend in valuing parameters that are broader than just symptom control, mortality, or life expectancy. It is understood as an individual's perceived position in life in the context of cultural and value systems, related to personal objectives, expectations, health, standards, and concerns [32]. It is a hybrid, biological and social concept that is not exclusively guided by clinical health to assess morbidity outcome [33].

A SMM episode and other severe health conditions, including a traumatic experience during childbirth, are considered to result in adverse effects in these surviving women and their children, family, and society [34–37]. However, scientific management of QOL is challenging. First, there is no consensual definition that can be applied. Second, the concept is linked to a subjective social and cultural burden based on people's self-perception of health status [38]. Recognition and assessment of repercussions of SMM on women's QOL are major steps to demonstrate its importance. This could draw attention to the need for resources also to more common disturbing events experienced by women, even a long period after childbirth [39].

Although there was not a clear association between maternal age and the perception of QOL, adolescent women had a lower mean score in domain 4, probably showing the impact of these new psychological, social, and economic responsibilities with motherhood [40]. Maternal morbid conditions are associated with both increasing and decreasing maternal age. Some studies found a strong association between advanced maternal age and SMM, in addition to higher risks of adverse neonatal outcomes [36, 41]. This is consistent with preexisting medical conditions that are more prevalent in older women.

Results of the physical component analysis (SF36 domains 1 to 4) showed that SMM group had lower scores, indicating that perception of QOL related to physical health may be associated with SMM, as already found elsewhere [10]. Remaining symptoms or “morbidities perceived” by women in the SMM group through their own criteria of severity, discomfort, or interference in daily living routine may have influenced the results [42]. Although this is not the scope of this current analysis, we identified 15 women who had died, nine of them from late maternal causes. We could assume that, if interviewed, they would probably have reported impairment in their QOL.

The SF36 general health component also had lower scores in women with SMM, as already similarly found [9]. Although general health status is correlated with the mental and physical components in SF36 [20], it is worth highlighting that general health status may have been influenced by the physical component, since mental health components showed no differences between groups. We believe that there is a complex interaction between physiological, psychological, and social factors, in addition to a subjective dimension in the disease process. Therefore, even though no significant differences were found in the perception of women's QOL in vitality, social aspects, emotional aspects, and mental health, it is not possible to separate mental and physical health.

Another factor that may have limited the influence of mental health in the global health score was the time elapsed from the event to the interview. Although we did not find differences in QOL when stratifying for time since delivery, longer time span may have favored more adaptive emotional and social responses of women, favoring the development of coping strategies and resulting in a more adapted emotional status.

Women with higher school education and with partners scored higher in the perception of general health status. This corroborates the concept that higher schooling is associated with a healthier lifestyle and access to healthcare and that a partner may offer social and financial support [43, 44]. Chronic conditions correlate with a worse perception of QOL, as our and other studies found for diabetes, hypertension, respiratory disease, HIV, and smoking [29, 45, 46].

The caesarean section was consistently associated with a worse score in domain 4 (QOL related to general health), drawing attention to the extent of postnatal morbidity after caesarean section. Similar results with worse SF36 scores for caesarean section were already reported before [29, 30].

From the results of this study, we can infer that women with severe maternal morbidity episodes, especially if life-threatening and coexistent with some chronic medical condition, who underwent caesarean section and were at the extremes of reproductive age, are at an increased risk of having a worse perception of quality of life, although some recent studies were not able to confirm such findings [47]. Particularly under these conditions, these women need special care. Actions are required to approach the complex interaction between different aspects involved in SMM. Further studies should consider the experience of a severe maternal morbidity as an important impact factor on the quality of life of women. In general, every woman diagnosed as maternal near miss should receive differential care in the postpartum period, either for monitoring clinical repercussions or for identifying difficulties of personal, social, and family reorganization after the experience of such a clinical event. The perception of quality of life does not only depend on the clinical criteria, but also depend on the woman's perception of the impact that an event such as maternal near miss has on her life in a comprehensive way. This screening can be performed in the puerperium by specific instruments such as SF-36 or with specific instruments, as recently proposed by the World Health Organization's maternal morbidity Working Group [48]. Follow-up should include a multiprofessional approach.

5. Conclusion

SF36 scores showed significant differences between groups of women exposed to SMM and controls in the domains of functional capacity (domain 1), physical aspects (domain 2), pain (domain 3), and general health status (domain 4). Lower scores in domain 4 were found when women had a lower level of school education, lived without a partner, and had given birth by caesarean section.

Such results may potentially have important implications for clinical practice. Although it is not possible to indicate a clear benefit in favor of any method of delivery, caesarean section was associated with lower scores in general health quality of life and this may have an alarming effect on women's lives, especially in countries that still have high C-section rates such as Brazil.

Even though some aspects of health perception are not necessarily medical or sanitary issues, obstetricians and interdisciplinary healthcare professionals, including primary care workers, must be aware of the potential impact of SMM on women's lives beyond the immediate postpartum period.

Acknowledgments

This study was fully sponsored by the Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq, Research Grant 471142/2011-5), which however played no role whatsoever in planning, implementing, analyzing, discussing results of, or writing the current manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CATI:

Computer-Assisted Telephone Interview

- ICU:

Intensive care unit

- MDG:

Millennium Development Goal

- PTSD:

Posttraumatic stress disorder

- SF36:

36-Item Short-Form Health Survey

- SMM:

Severe maternal morbidity

- QOL:

Quality of life

- WHO:

World Health Organization.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was assessed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (letter of approval CEP 233/2009).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors do not have conflicts of interest at all.

Authors' Contributions

The idea for and the first draft of the research proposal were developed by Jose G. Cecatti, Rodolfo C. Pacagnella, and Mary A. Parpinelli. The grant was obtained by Jose G. Cecatti. The study was implemented by Carina R. Angelini, Rodolfo C. Pacagnella, Mary A. Parpinelli, Carla Silveira, Carla B. Andreucci, Elton C. Ferreira, Juliana P. Santos, Dulce M. Zanardi, Renato T. Souza, and Jose G. Cecatti, including data collection and data management. The plan for this analysis was performed by Carina R. Angelini, Rodolfo C. Pacagnella, Jose G. Cecatti, and Maria H. Sousa. Maria H. Sousa performed the statistical analysis whose results were discussed among all authors. Carina R. Angelini wrote the first draft of the manuscript, after being reviewed by Jose G. Cecatti, Rodolfo C. Pacagnella, and Mary A. Parpinelli. All the coauthors gave important suggestions for the final version of the manuscript that was read and approved by all of them.

References

- 1.Victora C. G., Aquino E. M., Do Carmo Leal M., Monteiro C. A., Barros F. C., Szwarcwald C. L. Maternal and child health in Brazil: Progress and challenges. The Lancet. 2011;377(9780):1863–1876. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pacagnella R. C., Cecatti J. G., Camargo R. P., et al. Rationale for a Long-term Evaluation of the Consequences of Potentially Life-threatening Maternal Conditions and Maternal "Near-miss" Incidents Using a Multidimensional Approach. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2010;32(8):730–738. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34612-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koblinsky M., Chowdhury M. E., Moran A., Ronsmans C. Maternal morbidity and disability and their consequences: Neglected agenda in maternal health. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2012;30(2):124–130. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v30i2.11294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Storeng K. T., Drabo S., Ganaba R., Sundby J., Calvert C., Filippi V. Mortality after near-miss obstetric complications in Burkina Faso: Medical, social and health-care factors. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2012;90(6):418–425. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.094011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Souza J. P., Cecatti J. G., Parpinelli M. A., Krupa F., Osis M. J. D. An emerging "maternal near-miss syndrome": Narratives of women who almost died during pregnancy and childbirth. Women and Birth. 2009;36(2):149–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furuta M., Sandall J., Bick D. A systematic review of the relationship between severe maternal morbidity and post-traumatic stress disorder. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2012;12, article no. 125 doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furuta M., Sandall J., Cooper D., Bick D. The relationship between severe maternal morbidity and psychological health symptoms at 6-8 weeks postpartum: A prospective cohort study in one English maternity unit. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2014;14(1, article no. 133) doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glazener C. M. A. Sexual function after childbirth: Women's experiences, persistent morbidity and lack of professional recognition. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1997;104(3):330–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waterstone M., Wolfe C., Hooper R., Bewley S. Postnatal morbidity after childbirth and severe obstetric morbidity. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2003;110(2):128–133. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2003.02151.x. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2003.02151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filippi V., Ganaba R., Baggaley R. F., et al. Health of women after severe obstetric complications in Burkina Faso: a longitudinal study. The Lancet. 2007;370(9595):1329–1337. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61574-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andreucci C. B., Cecatti J. G., Pacagnella R. C., et al. Does severe maternal morbidity affect female sexual activity and function? Evidence from a Brazilian cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143581.e0143581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Storeng K. T., Murray S. F., Akoum M. S., Ouattara F., Filippi V. Beyond body counts: A qualitative study of lives and loss in Burkina Faso after 'near-miss' obstetric complications. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(10):1749–1756. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lydon-Rochelle M. T., Holt V. L., Martin D. P. Delivery method and self-reported postpartum general health status among primiparous women. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2001;15(3):232–240. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tunçalp Ö., Hindin M. J., Adu-Bonsaffoh K., Adanu R. Listening to Women's Voices: The Quality of Care of Women Experiencing Severe Maternal Morbidity, in Accra, Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044536.e44536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cecatti J. G., Souza J. P., Parpinelli M. A., et al. Brazilian network for the surveillance of maternal potentially life threatening morbidity and maternal near-miss and a multidimensional evaluation of their long term consequences. Reproductive Health. 2009;6(1, article 15) doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-6-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Say L., Souza J. P., Pattinson R. C. Maternal near miss—towards a standard tool for monitoring quality of maternal health care. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2009;23(3):287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown S., Lumley J. Physical health problems after childbirth and maternal depression at six to seven months postpartum. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;107(10):1194–1201. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGovern P., Dowd B., Gjerdingen D., et al. Postpartum health of employed mothers 5 weeks after childbirth. Annals of Family Medicine. 2006;4(2):159–167. doi: 10.1370/afm.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciconelli R. M., Ferraz M. B., Santos W., Meinao I., Quaresma M. R. Translation to Portuguese and validation of the generic questionnaire on assessment of quality of life SF-36 (Brazil SF-36) Brasileira de Reumatologia. 1999;39(3):143–50. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ware J. E. SF-36 health survey update. The Spine Journal. 2000;25(24):3130–3139. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cecatti J. G., Camargo R. P. S., Pacagnella R. C., et al. Computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI): Using the telephone for obtaining information on reproductive health. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2011;27(9):1801–1808. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2011000900013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boekhout A. H., Maunsell E., Pond G. R., et al. A survivorship care plan for breast cancer survivors: extended results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2015;9(4):683–691. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0443-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riesenberg D., Glass R. M. The Medical Outcomes Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;262(7):p. 943. doi: 10.1001/jama.1989.03430070091038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simeão S. F. D. A. P., Landro I. C. R., De Conti M. H. S., Gatti M. A. N., Delgallo W. D., De Vitta A. Quality of life of groups of women who suffer from breast cancer. Ciencia & Saúde Coletiva. 2013;18(3):779–788. doi: 10.1590/S1413-81232013000300024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castro P. C., Driusso P., Oishi J. Convergent validity between SF-36 and WHOQOL-BREF in older adults. Revista de Saúde Pública. 2014;48(1):63–67. doi: 10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048004783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoedjes M., Berks D., Vogel I., et al. Poor Health-related Quality of Life After Severe Preeclampsia. Women and Birth. 2011;38(3):246–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2011.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amino N., Izumi Y., Hidaka Y. Community postnatal care and women's health. The Lancet. 2001;360(3):p. 410. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09579-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill P. D., Aldag J. C. Maternal perceived quality of life following childbirth. JOGNN - Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2007;36(4):328–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van der Woude D. A. A., Pijnenborg J. M. A., de Vries J. Health status and quality of life in postpartum women: a systematic review of associated factors. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2015;185:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prick B. W., Bijlenga D., Jansen A. J. G., et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life in the postpartum period after obstetric complications. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2015;185:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gausia K., Ryder D., Ali M., Fisher C., Moran A., Koblinsky M. Obstetric complications and psychological well-being: Experiences of Bangladeshi women during pregnancy and childbirth. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2012;30(2):172–180. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v30i2.11310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. The World health report 2005: make every mother or child count. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minayo M. C., Hartz Z. M., Buss P. M. Qualidade de vida e saúde: um debate necessário. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2000;5(1):7–18. doi: 10.1590/S1413-81232000000100002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Research Council. The Consequences of Maternal Morbidity and Maternal Mortality: Report of a Workshop”, Committee on Population. In: Reed H. E., Koblinsky M. A., Mosley W. H., editors. Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davydow D. S., Gifford J. M., Desai S. V., Bienvenu O. J., Needham D. M. Depression in general intensive care unit survivors: A systematic review. Intensive Care Medicine. 2009;35(5):796–809. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1396-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Camargo R. S., Pacagnella R. C., Cecatti J. G., Parpinelli M. A., Souza J. P., Sousa M. H. Subsequent reproductive outcome in women who have experienced a potentially life-threatening condition or a maternal near-miss during pregnancy. Clinics. 2011;66(8):1367–1372. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000800010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bastos M. H. E., Furuta M., Small R., McKenzie-McHarg K., Bick D. Debriefing interventions for the prevention of psychological trauma in women following childbirth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;4:p. CD007194. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007194.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farquhar M. Definitions of quality of life: a taxonomy. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1995;22(3):502–508. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.22030502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacArthur C., Winter H. R., Bick D. E., et al. Effects of redesigned community postnatal care on womens' health 4 months after birth: A cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2002;359(9304):378–385. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07596-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sabroza A. R., Leal M. D. C., Souza P. R. D., Jr., Gama S. G. N. D. Some emotional repercussions of adolescent pregnancy in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (1999-2001) Cadernos de saúde pública / Ministério da Saúde, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública. 2004;20:S130–137. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2004000700014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laopaiboon M., Lumbiganon P., Intarut N., et al. Advanced maternal age and pregnancy outcomes: a multicountry assessment. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2014;121:49–56. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sadana R. Measuring reproductive health: Review of community-based approaches to assessing morbidity. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000;78(5):640–654. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Graaf J. P., Steegers E. A. P., Bonsel G. J. Inequalities in perinatal and maternal health. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013;25(2):98–108. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32835ec9b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi H., Marks N. F. Marital Quality, Socioeconomic Status, and Physical Health. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2013;75(4):903–919. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alonso J., Ferrer M., Gandek B., et al. Health-related quality of life associated with chronic conditions in eight countries: results from the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. Quality of Life Research. 2004;13(2):283–298. doi: 10.1023/b:qure.0000018472.46236.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trevisol D. J., Moreira L. B., Kerkhoff A., Fuchs S. C., Fuchs F. D. Health-related quality of life and hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Journal of Hypertension. 2011;29(2):179–188. doi: 10.1097/hjh.0b013e328340d76f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Norhayati M. N., Nik Hazlina N. H., Aniza A. A. Immediate and long-term relationship between severe maternal morbidity and health-related quality of life: A prospective double cohort comparison study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1, article no. 818) doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3524-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chou D., Tunçalp Ö., Firoz T., et al. Constructing maternal morbidity - towards a standard tool to measure and monitor maternal health beyond mortality. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2016;16(1, article no. 45) doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0789-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.