Abstract

Background

Angiomyofibroblastoma (AMFB) is a benign mesenchymal tumor most commonly found in the female genital tract of premenopausal women. Although rare, AMFB is an important consideration in the differential diagnosis of vulvar and vaginal masses, as it must be distinguished from aggressive angiomyxoma (AA), a locally recurrent, invasive, and damaging tumor with similar clinical and pathologic findings.

Case

We describe a patient with a 4 cm vaginal AMFB and the relevant preoperative radiographic imaging findings.

Conclusion

Preoperative diagnosis of AMFB remains difficult. Common findings on magnetic resonance imaging and transvaginal sonography are described. We conclude that both transvaginal ultrasound and MRI are potentially useful imaging modalities in the preoperative assessment of vulvar and vaginal AMFB, with more data needed to determine superiority of one modality over the other.

1. Introduction

Angiomyofibroblastoma (AMFB) is a rare, indolent mesenchymal tumor that most commonly occurs in the female genital tract in premenopausal women, most frequently in the vulva and vagina. AMFB typically measures less than 5 cm; however, case reports describe tumors of up to 23 cm in size [1]. Few cases have been reported affecting the fallopian tube, ischiorectal fossa, cervix, and bladder, as well as similar tumors in the male spermatic cord, scrotum, and perineum [2–6].

AMFB was first described in the literature by Fletcher et al. in 1992 as an important distinction from aggressive angiomyxoma (AA), which is an infiltrative myxedematous mesenchymal tumor with the potential for local recurrence [7].

Preoperative diagnosis of AMFB and distinction from other soft tissue tumors is often difficult, as there is limited information on characteristic imaging findings. The differential diagnosis for a vaginal or vulvar mass includes Bartholin's gland cyst, epidermal inclusion cyst, Gartner's duct cyst, fibroma, lipoma, hemangioma, leiomyoma, and alternative rare mesenchymal tumors. Here, we describe a case report of a vaginal AMFB and relevant radiologic features to aid in diagnosis and distinction from aggressive angiomyxoma.

2. Case

A 30-year-old gravida 1 para 1 female presented to our Emergency Department complaining of a vaginal mass present since the birth of her child 4 years earlier. At that time, she underwent an uncomplicated vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery and was unaware of significant lacerations or repairs. She felt that the mass had not changed significantly in size since the postpartum period, but she had never been evaluated by a physician. She complained of acutely worsening discharge over the previous month, described as watery yellow to pink and occasionally blood tinged. She denied changes in bowel movements, dysuria, hematuria, fevers, chills, night sweats, changes in appetite, or weight loss. She complained of both entry and deep dyspareunia.

Physical exam was notable for copious serosanguinous fluid within the vaginal vault. A well-circumscribed, smooth cystic structure approximately 4 cm in diameter was noted along the posterior vaginal wall. There was also a 0.5x1.0 cm exophytic lesion overlying the mass with serosanguinous drainage (Figure 1). On rectal exam, the mass was noted to be separate from the cervix and within the rectovaginal septum. Rectal involvement was not appreciated.

Figure 1.

Lesion on exam under anesthesia and gross specimen during dissection.

Tissue biopsies were taken; however, they were of limited diagnostic value, showing fibrous tissue with acute and chronic inflammation and squamous debris, consistent with cyst wall and contents.

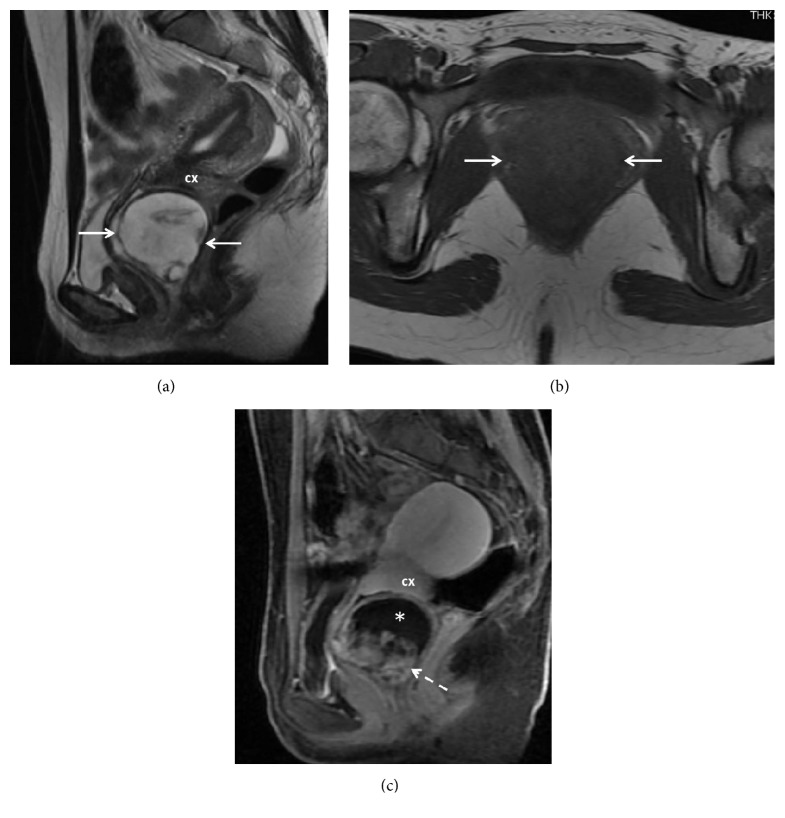

A pelvic ultrasound (US) was performed and showed a complex vaginal mass, inseparable from the cervix, measuring 5.1 x 3.8 x 5.4 cm (Figure 2(a)). Color Doppler demonstrated minimal peripheral vascularity (Figure 2(b)). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was subsequently performed for further characterization (Figure 3). The mass measured 4.7 x4.8 x 4.9 cm and appeared to arise from the posterior wall of the vagina, separate from the cervix. The mass was heterogeneously hyperintense on T2-weighted (T2W) images and hypointense on T1-weighted (T1W) images. Postcontrast sequences demonstrated enhancement of the wall, absent internal enhancement superiorly, and bulky, nodular, hyperenhancement inferiorly, consistent with a complex cystic mass.

Figure 2.

Transvaginal ultrasound. (a) Gray scale image shows a mixed echogenicity mass (arrows) with small hypoechoic cystic areas (3.0 MHz) 10 cm. (b) Color Doppler image shows minimal vascularity. Magnitude: 3 MHz.

Figure 3.

(a) Sagittal T2 weighted image shows a predominantly hyperintense mass (arrows) with small central areas of hypointensity. (b) On T1 weighted axial image the mass is homogeneously hypointense (arrows). (c) Sagittal contrast enhanced image demonstrates heterogeneous hyperenhancement inferiorly (dashed arrow) and absent enhancement superiorly (∗). Cervix: cx.

The patient was taken to the operating room for an uncomplicated surgical excision. Histology was notable for hypocellular edematous myxoid stromal tissue alternating with hypercellular areas of stromal cells clustered around thin walled small to medium-sized vessels, consistent with angiomyofibroblastoma. Stromal cells were noted to be spindled with eosinophilic cytoplasm. Nuclei were round or ovular with fine chromatin (Figure 4). Rare mitotic figures were noted. Immunohistochemical stains were negative for desmin, alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and progesterone receptor but demonstrated focal estrogen receptor positivity.

Figure 4.

(a) Mesenchymal lesion with alternating hypercellular and hypocellular areas (4x magnification; hematoxylin and eosin stain). (b) Higher magnification demonstrating ovoid and spindle-shaped cells aggregated around small blood vessel (40x magnification).

3. Comment

Although AMFB is a rare diagnosis, it is an important consideration in the premenopausal and perimenopausal patient presenting with a vulvovaginal mass given its predilection for this region of the female genital tract. In a review of the literature in 2015 by Wolf et al., 125 cases of female AMFB had been previously reported, of which 92% were either vulvar (N = 98) or vaginal in origin (N = 17). Median age was 45, and the majority of cases were observed in women less than 60 years of age [8]. Since 2015, there have been 10 additional cases including ours describing AMFB in females, six of which were located in the vulva, one cervical, one in the broad ligament, and one on the patient's foot [2, 9–17]. All women were under the age of 50.

Differential diagnosis for AMFB includes Gartner's duct cyst, epidermal inclusion cyst, leiomyoma, and fibroepithelial polyps among the more common etiologies. It is most important to distinguish AMFB from aggressive angiomyxoma (AA), which can commonly be misdiagnosed based on anatomic and pathologic similarities (Table 1). Although there have been no reports of distant metastasis, AA is known to recur in 33-72% of cases and is locally invasive, often entrapping nerves and mucosal glands [18, 19]. Surgical approach to AA requires wide local excision given the infiltrative nature of the lesion versus simple excision of AMFB; thus, it is important to attempt differentiation between the two prior to surgery.

Table 1.

Clinical and pathologic features of AMFB and AA.

| AMFB | AA | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical features | ||

| Age (years) | 16 – 86 (Median 45) | 16 – 70 (Median 37) |

| Size (cm) | < 5 (0.5 – 23) | >5 (1-60) |

| Location | Female pelvis and perineum: predominantly vulvar/vaginal | Female pelvis and perineum |

| Onset | 1 month to 8 years | 1 month – 5 years |

| Predominantly 1-2 years | Predominantly < 1 year | |

| Recurrence | None reported | 33-72% |

| Pathology | ||

| Low-power features | Well-defined | Infiltrative |

| No entrapment of mucosal glands or nerve bundles | Entrapped mucosal glands and nerve bundles | |

| Alternating hypocellular and hypercellular areas | Stromal cells distributed throughout | |

| Vasculature | Abundant thin-walled vessels, mostly capillary-like | Small to medium-sized vessels, mostly thick-walled or hyalinized |

| Stromal cells | Abundant | Low cellularity |

| Spindle, plump spindle, or oval | Thin delicate spindle or stellate | |

| Perivascular aggregation | Mitotic figures typically absent | |

| Mitotic figures typically absent | ||

| Stroma | Mucin-poor, containing delicate, wavy collagen fiber | Myxoid, hyaluronic-acid rich |

| Immunostaining | ||

| Desmin | Positive (50-60%) | Positive (Up to 73%) |

| α –SMA | Negative (positive in up to 15%) | Positive |

| S-100 | Negative | Negative |

| Vimentin | Positive | Positive |

| Estrogen receptor | Positive | Positive |

| Progesterone receptor | Positive | Positive |

Diagnostic utility of preoperative imaging for AMFB remains controversial. However, as the number of reported cases increases in the literature, more data exists on common radiographic features (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristic imaging features of AMFB on MRI and US.

| Study | Sex | Age | Size (cm) | Location | MRI | TVUS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wolf et al. | F | 38 | 9x6x1.5 | Vagina | T1 weighted: Homogenous hypointense | Well-demarcated, homogenous mass, medium echogenicity, few septations |

| T2-weighted: Homogenous hypointense mass | Doppler: several small intralesional vessels | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Souza et al. | M | 19 | 2.8 | Scrotum | T1-weighted: Central hypointensity Intermediate hyperintensity, capsule | Well-defined, heterogeneous echo texture, small hypoechoic cysts |

| T2-weighted: Intermediate homogenous hyperintensity, Hypointense capsule Central heterogeneous mixed hypo and hyperintensity |

Doppler: minimal flow | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Shoji et al. | F | 50 | 8x7x5 | Vulva | T1-weighted: Hypointense mass | N/A |

| GA-T1: Homogenous enhancement, poorly enhanced area at center | ||||||

| T2-weighted: Mildly hyperintense | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Geng et al. | F | 46 | 8.5x6x16 | Paravaginal | T1-weighted: signal intensity similar to skeletal muscle | N/A |

| GA-T1: Homogenous hyperintensity | ||||||

| T2-weighted: Hyperintensity, mild hyperintensity mild hypointensity | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Kim et al. | F | 40 | 9x5.5x2.5 | Vulva | N/A | Mixed echoic soft tissue massHyperechoic areas mixed with irregular hypoechoic areas with tiny hypoechoic components |

| Doppler: negative | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Qiu et al. | F | 32 | 13.2x5.8 x7.8 | Posterior cul-de-sac | N/A | Moderately echoic mass, small hypoechoic area |

| Doppler: N/A | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Kitamura et al. | F | 24 | 3 x 2.8 x 2.8 | Urethra | T1-weighted: N/A | N/A |

| T2 Weighted: homogenous, well-defined, low to moderate hyperintensity | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Lim et al. | F | 48 | 3.8x3.5x2.8 | Posterior perivesical space | T1-weighted: Signal intensity similar to skeletal muscle | N/A |

| GA-T1: Strong homogenous enhancement | ||||||

| T2-weighted: well-defined mass heterogeneous intermediate signal intensity, focal nodular and central curvilinear dark signal intensities | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Maruyama et al. | M | 72 | 7.2x5.5x2.2 | Scrotum | T1-weighted: Similar to or lower signal intensity than skeletal muscle | Mixed echogenicity, with several small hypoechoic cystic areas∗ |

| GA-T1: strong heterogeneous enhancement | ||||||

| T2-weighted: heterogeneous intermediate to high signal intensity | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Wang et al. | F | N/A | N/A | Anterior vaginal | N/A | Poorly defined, irregularly shaped, hypoechoic, band-like echoes of various width |

| Doppler: positive blood flow | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Wang et al. | F | N/A | N/A | Urethral | N/A | Well-defined, hypoechoic cystic solid mass |

| Doppler: positive blood flow | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Mortele et al. | F | 46 | Perineal | 2.5x3.5 | T1-weighted: hypointense, inhomogeneous mass with small focus of hyperintensity representing fat | N/A |

| GA-T1: Strong homogenous uptake | ||||||

| T2-weighted: Hyperintense homogenous signal similar to surrounding fat | ||||||

3.1. Ultrasonography

US is typically the first imaging modality used to evaluate vaginal masses due to its intrinsic high resolution, availability, and cost effectiveness. US can be utilized to distinguish vulvar and vaginal AMFB from AA and other mesenchymal tumors [20, 21]. AMFB shows hyperechoic areas with irregular and small hypoechoic cystic areas interspersed within homogenous echogenic stroma [8, 20–23]. Minimal vascularity in AMFB is occasionally noted [8, 22]. Absence of prominent vascularity on color Doppler is consistent histologically with the predominant capillary-like vascular component of AMFB. Echogenic areas have been shown to represent hypocellular stroma on histology, while hypoechogenicity represents hypercellular areas [8, 21]. In our case, US characteristics were similar to those previously described.

In contrast, US appearance of AA is typically a hypoechoic mass with homogenous echogenicity and occasional echogenic septa correlating to fibrous bands on pathology [24, 25]. These fibrous bands can create a layered or swirling appearance similar to that seen on MRI and CT imaging of AA [26]. Vascularity can also be much more prominent on color Doppler of AA than AMFB [26, 27].

To complete the differential diagnosis, vaginal wall cysts are anechoic masses without internal vascularity; vaginal epidermoid cysts are homogeneous hyperechoic masses without internal vascularity; and heterogeneous solid masses are often malignancies or leiomyoma [22].

3.2. Magnetic Resonance Imaging

On MRI, AMFB is typically well circumscribed [9]. It is rare to see central necrosis or degeneration but it does not rule out AMFB [9]. AMFB is most often described as hypointense on T1 weighted (T1W) images, similar to that of skeletal muscle, hyperintense on T2 weighted (T2W) images, and with homogenous hyperenhancement on gadolinium chelate (Gd-C) enhanced images [1, 9, 23, 28]. Differences in T1W and T2W signal intensity may be attributable to variations in lipid and collagenous content in AMFB [8, 23, 28–31].

Contrast enhanced imaging was only reported in 5 studies. Four showed homogenous hyperenhancement and one demonstrated heterogeneous enhancement [23]. Hyperenhancement is thought to be related to prominent vascularity associated with myofibroblast tumors and AMFB in particular [1, 9, 23, 28, 30–32].

Our case demonstrated heterogeneously high T2 and low T1 signaling intensity on MRI which is consistent with the literature. Postcontrast sequences demonstrated enhancement of the wall, absent internal enhancement superiorly, and bulky nodular enhancement inferiorly, consistent with a complex cystic mass.

When correlated histologically, hyperintensity on T2W and absent enhancement correspond to hypocellular areas with abundant collagenous stroma. Areas of hyperenhancement correspond to areas of hypercellularity and vascularity, with little collagenous stroma and water content. Intermediate intensity on T2W and less avid enhancement are thought to represent areas of intermediate cellularity and collagenous stroma [28].

Data on MRI characteristics of AA is limited. AA has similar findings to AMFB on T1W and T2W images but is thought to be differentiated best by its enhancement characteristics. AA is described as having an intense, swirled or layered pattern. Similar swirling and layered enhancement is also described on contrast enhanced CT [26–28, 33–36]. AMFB does not typically show infiltrative pattern but it can grow around structures. If infiltration and swirled or layered pattern are observed, AA is much more likely than AMFB [28, 34–36].

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, in the patient with a vaginal or vulvar mass, it is important to consider AMFB among the differential diagnoses, particularly because of the importance of distinguishing AMFB from AA for treatment purposes. Postoperative histologic examination is needed for definitive diagnosis; however, we propose that ultrasound and MRI are increasingly useful diagnostic tools, particularly as the number of reported cases increases. Given the cost effectiveness of ultrasound, initiating imaging workup of a solid vaginal or vulvar mass with ultrasonography is suggested.

Data Availability

The magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound data used to support the findings of this study can be found within the cited articles in this study. Please refer to Table 2 for a complete list of imaging studies included in this review. Patient images used to support findings of this case report study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional Points

Precis. Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging are useful modalities in the diagnosis of angiomyofibroblastoma, a rare mesenchymal tumor. Teaching Points. (1) AMFB occurs in the vulva and vagina in over 90% of reported cases: AMFB should be considered on the differential diagnosis of benign appearing vulvar and vaginal masses. (2)Transvaginal ultrasound is the recommended first line imaging for AMFB. MRI is recommended as second-line imaging and is preferable to CT. (3) It is important to attempt preoperative distinction from aggressive angiomyxoma in order to optimize surgical approach.

Conflicts of Interest

All the authors have no conflicts of interest for this study.

References

- 1.Nagai K., Aadachi K., Saito H. Huge pedunculated angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva. International Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;15(2):201–205. doi: 10.1007/s10147-010-0026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roncati L., Pusiol T., Piscioli F., Barbolini G., Maiorana A. Undetermined cervical smear due to angiomyofibroblastoma of the cervix uteri. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2017;37(6):829–830. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2017.1303467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kobayashi T., Suzuki K., Arai T., Sugimura H. Angiomyofibroblastoma arising from the fallopian tube. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1999;94(Supplement):833–834. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199911001-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding G., Yu Y., Jin M., Xu J., Zhang Z. Angiomyofibroblastoma-like tumor of the scrotum: A case report and literature review. Oncology Letters. 2014;7(2):435–438. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deka P. M., Bagawade J. A., Deka P., Baruah R., Shah N. A Rare Case of Intravesical Angiomyofibroblastoma. Urology. 2017;106:e15–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tzanakis N. E., Giannopoulos G. A., Efstathiou S. P., Rallis G. E., Nikiteas N. I. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the spermatic cord: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2010;4(1) doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fletcher C. D. M., Tsang W. Y. W., Fisher C., Lee K. C., Chan J. K. C. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva: A benign neoplasm distinct from aggressive angiomyxoma. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 1992;16(4):373–382. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199204000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolf B., Horn L.-C., Handzel R., Einenkel J. Ultrasound plays a key role in imaging and management of genital angiomyofibroblastoma: A case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2015;9(1, article no. 248) doi: 10.1186/s13256-015-0715-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shoji T., Takeshita R., Mukaida R., Sato T., Taguchi M., Sasou S. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva diagnosed preoperatively: A case report. Molecular and Clinical Oncology. 2017;7(3):407–411. doi: 10.3892/mco.2017.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang H. C., Chen Y. R., Tsai H. D., Cheng Y. M., Hsiao Y. H. Angiomyofibroblastoma the Broad Ligament: A Case Report. International Journal of Gynecological Pathology. 2017;36(5):471–475. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong Y. P., Tan G. C., Ng P. F. Cervical angiomyofibroblastoma: a case report and review of literature. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2017;37(5):681–682. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2017.1281236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salunke A. A., Chen Y., Lee V. K., Puhaindran M. E. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the Foot: a Rare Soft Tissue Tumor at Unusual Site. Indian Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2017;8(2):210–213. doi: 10.1007/s13193-016-0565-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oh S., Sung D. J., Sim K. C., et al. A rare case of vulvar angiomyofibroblastoma: MRI findings and literature review. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2017;37(6):831–833. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2017.1306035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Islam M., Afzal S., Majeed M., Monjur F., Parowary D. Angiomyofibroblastoma Vulva in a Very Young Adult Female: A Rare Case Report. Mymensingh Medical Journal. 2017;26(1):208–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsukuma S., Koga A., Suematsu R., Takeo H., Sato K. Lipomatous angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva: A case report and review of the literature. Molecular and Clinical Oncology. 2017;6(1):83–87. doi: 10.3892/mco.2016.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nili F., Nicknejad N., Salarvand S., Akhavan S. Lipomatous Angiomyofibroblastoma of the Vulva. International Journal of Gynecological Pathology. 2017;36(3):300–303. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelincik I., Yildirim A., Sayar I., Aktas C. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the right labia major. Indian Journal of Pathology and Microbiology. 2016;59(2):p. 257. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.182033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fetsch J. F., Laskin W. B., Lefkowitz M., Kindblom L., Meis-Kindblom J. M. Aggressive angiomyxoma: A clinicopathologic study of 29 female patients. Cancer. 1996;78(1):79–90. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960701)78:1<79::AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bégin L. R., Clement P. B., Kirk M. E., Jothy S., Elliott McCaughey W. T., Ferenczy A. Aggressive angiomyxoma of pelvic soft parts: a clinicopathologic study of nine cases. Human Pathology. 1985;16(6):621–628. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(85)80112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu P., Wang Z., Li Y., Cui G. Giant pelvic angiomyofibroblastoma: case report and literature review. Diagnostic Pathology. 2014;9(1):p. 106. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-9-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S. W., Lee J., Han J. K., Jeon S. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the Vulva. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2009;28(10):1417–1420. doi: 10.7863/jum.2009.28.10.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X., Yang H., Zhang H., Shi T., Ren W. Transvaginal sonographic features of perineal masses in the female lower urogenital tract: A retrospective study of 71 patients. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2014;43(6):702–710. doi: 10.1002/uog.13251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maruyama M., Yoshizako T., Kitagaki H., Araki A., Igawa M. Magnetic resonance imaging features of angiomyofibroblastoma-like tumor of the scrotum with pathologic correlates. Clinical Imaging. 2012;36(5):632–635. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Catalano O. Case report: Aggressive angiomyxoma of the pelvic soft tissues: US and CT findings. Clinical Radiology. 1998;53(10):782–783. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(98)80327-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De La Ossa M., Castellano-Sanchez A., Alvarez E., Smoak W., Robinson M. J. Sonographic appearance of aggressive angiomyxoma of the scrotum. Journal of Clinical Ultrasound. 2001;29(8):476–478. doi: 10.1002/jcu.10005. doi: 10.1002/jcu.10005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tariq R., Hasnain S., Siddiqui MT., Ahmed R. Aggressive angiomyxoma: swirled configuration on ultrasound. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association. 2014;64(3):345–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen H., Zhao H., Xie Y., Jin M. Clinicopathological features and differential diagnosis of aggressive angiomyxoma of the female pelvis. Medicine. 2017;96(20):p. e6820. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geng J., Hu S., Wang F. Large paravaginal angiomyofibroblastoma: Magnetic resonance imaging findings. Japanese Journal of Radiology. 2011;29(2):152–155. doi: 10.1007/s11604-010-0512-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laskin W. B., Fetsch J. F., Tavassoli F. A. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the female genital tract: Analysis of 17 cases including a lipomatous variant. Human Pathology. 1997;28(9):1046–1055. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(97)90058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitamura H., Miyao N., Sato Y., Matsukawa M., Tsukamoto T., Sato T. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the female urethra. International Journal of Urology. 1999;6(5):268–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.1999.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyoung J. L., Jeung H. M., Dae Y. Y., Ji H. C., In J. L., Seon J. M. Angiomyofibroblastoma arising from the posterior perivesical space: A case report with MR findings. Korean Journal of Radiology. 2008;9(4):382–385. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2008.9.4.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mortele K. J., Lauwers G. J., Mergo P. J., Ros P. R. Perineal angiomyofibroblastoma: CT and MR findings with pathologic correlation. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 1999;23(5):687–689. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199909000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li X., Ye Z. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the pelvis and perineum: a case report and review of the literature. Abdominal Imaging. 2011;36(6):739–741. doi: 10.1007/s00261-010-9677-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeyadevan N. N., Sohaib S. A. A., Thomas J. M., Jeyarajah A., Shepherd J. H., Fisher C. Imaging features of aggressive angiomyxoma. Clinical Radiology. 2003;58(2):157–162. doi: 10.1053/crad.2002.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chien A. J., Freeby J. A., Win T. T., Gadwood K. A. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the female pelvis: Sonographic, CT, and MR findings. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1998;171(2):530–531. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.2.9694499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stewart S. T., McCarthy S. M. Case 77: aggressive angiomyxoma. Radiology. 2004;233(3):697–700. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2333021670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound data used to support the findings of this study can be found within the cited articles in this study. Please refer to Table 2 for a complete list of imaging studies included in this review. Patient images used to support findings of this case report study are available from the corresponding author upon request.