Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is an important public health problem worldwide.1 As of June 1999, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 169.7 million persons (3% of the world’s population) were chronically infected with HCV globally and that 3 to 4 million persons are newly infected each year.2 The prevalence rate was estimated to be 5.3% in Africa (31.9 million cases), 4.6% in the Eastern Mediterranean region (21.3 million cases), 3.9% in the West Pacific region (62.2 million cases), 2.15% in Southeast Asia (32.3 million cases), 1.7% in the Americas (13.1 million cases), and 1.03% in Europe (8.9 million cases).1 Data on the prevalence of HCV infection in Saudi Arabia is limited. The objective of this study was to describe the number of HCV infections reported in Saudi Arabia during 11 years of surveillance from January 1995 through December 2005.

METHODS

Saudi Arabia occupies most of the Arabian Peninsula with an area of about 2 240 000 sq km. It comprises 13 administrative provinces, namely, Makkah province (which includes the holy city of Makkah, Jeddah and Tayef ), Madinah province (which includes the holy city of Madinah), Riyadh province (which includes the capital city, Riyadh), the Eastern province (which includes Dammam, Ahsa, and Hafr Albaten), Asir province (which includes Abha and Bisha), Jouf province (which includes Jouf and Qerayyat), Hudud Shamaliyah (North Borders) province (which includes Arar), and Baha, Jizan, Najran, Hail, Qassim, and Tabook provinces. The latest census conducted in Saudi Arabia in 2004 indicated that the total population was 22 673 538, of whom, 16 529 302 (72.9%) subjects were Saudis. Approximately, 40.8% of the population is below 15 years. 56.1% are 15 to 64 years, and 3.1% are above 64 years of age. The population annual growth rate is 3.3%. The infant mortality rate is 19.1 per 1000 live births and the maternal mortality rate is 1.8 per 10,000 live births. The total life expectancy at birth is 71.4 years.

HCV infection and other causes of acute or chronic viral hepatitis have been notifiable in Saudi Arabia since 1990. Ministry of Health officials rely on healthcare providers, laboratories, and other public health personnel to report the occurrence of these infections to the Department of Preventive Medicine in the Central Ministry of Health office in Riyadh, where all surveillance data are compiled. HCV infection during the study period was identified by detection of antibodies to HCV (anti-HCV) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and the confirmatory recombinant immunoblot analyses (RIBA). Indications for testing for anti-HCV included clinical suspicion and routine screening of blood and organ donors, contacts of HCV-infected patients, prisoners, intravenous drug users, patients with other sexually transmitted infections, and expatriates pre-employment.

RESULTS

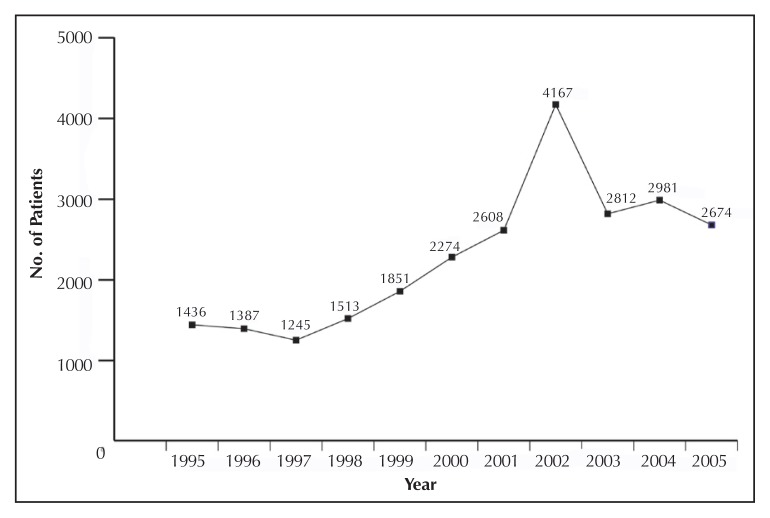

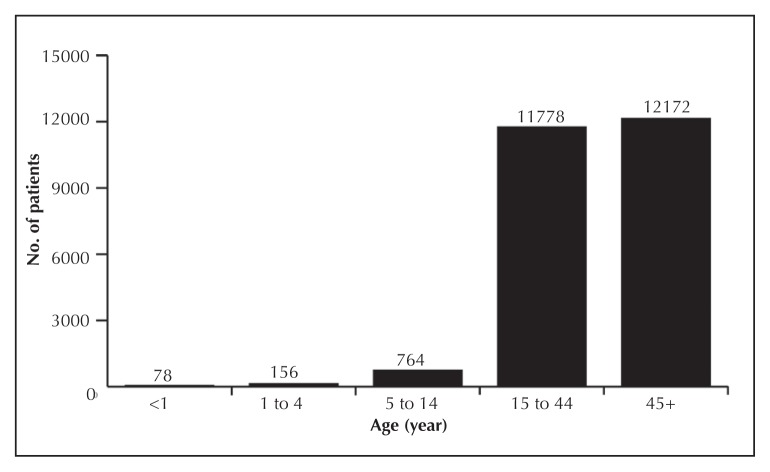

From January 1995 through December 2005, 24 948 cases with HCV infection were reported to the Ministry of Health, of whom 19 185 (76.9%) cases were Saudis. The number of cases by regions is shown in Table 1. The number of HCV infections by region ranged from 33 to 9186 cases with a mean of 1247 cases per region. Figure 1 shows the number of HCV cases by year. Figure 2 shows the number of cases by age groups. The mean size of the pediatric (children <15 years of age) and adult (subjects ≥15 years of age) population during the study period was 8 186 369 and 11 878 260 individuals, respectively. The total number of HCV cases reported among children was 998 cases and that among adults was 23 950 cases.

Table 1.

Number of subjects with antibodies to hepatitis C virus per 100 000 population by regions in Saudi Arabia (1995–2005).

| Region | No. of reported cases | Mean population during the surveillance period |

|---|---|---|

| Baha | 1268 | 393 327 |

| Jeddah | 9186 | 2 866 113 |

| Najran | 734 | 356 250 |

| East | 3522 | 1 824 952 |

| Qunfoda | 102 | 55 725 |

| Makkah | 2022 | 1 483 258 |

| Riyadh | 4159 | 4 538 346 |

| Qassim | 812 | 890 625 |

| Bisha | 218 | 288 321 |

| Tabook | 389 | 575 000 |

| Madina | 808 | 1 283 251 |

| Jouf | 112 | 205 882 |

| Asir | 568 | 1 297 311 |

| Ahsa | 351 | 940 217 |

| Qerayyat | 33 | 113 393 |

| Hail | 143 | 487 778 |

| North Borders | 78 | 270 808 |

| Tayef | 221 | 883 186 |

| Hafr Albaten | 62 | 280 727 |

| Jizan | 160 | 1 030 159 |

| Total | 24 948 | 20 064 629 |

Figure 1.

Number of cases of hepatitis C virus infection by year.

Figure 2.

Number of cases of hepatitis C virus infection by age group.

DISCUSSION

In 1989, HCV was first identified and found to be responsible for most transfusion-associated non-A non-B viral hepatitis.3,4 Before HCV identification, the major causes of HCV infection worldwide were the use of unscreened blood transfusions, and re-use of needles and syringes that were not adequately sterilized. Screening of blood and organ donors for HCV since 1990 has virtually eliminated the spread of HCV by these routes. Consequently, sharing contaminated needles has become the most common mode of transmission of this infection.1 Sexual and perinatal transmission may also occur, although less frequently.5–7 Infection via other modes of transmission such as ear and body piercing, circumcision, tattooing, and cupping (Hijama) can occur if inadequately sterilized equipment is used.2

The prevalence of anti-HCV in some neighboring and other Islamic countries was reported as follows: Algeria, 0.2%, Egypt, 18.1%, Indonesia, 2.1%, Iraq, 0.5%, Jordan, 2.1%, Kuwait, 3.3%, Libya, 7.9%, Malaysia, 3.0%, Mauritania, 1.1%, Morocco, 1.1%, Oman, 0.9%, Pakistan, 2.4%, Qatar, 2.8%, Somalia, 0.9%, Sudan, 3.2%, Tunisia, 0.7%, Turkey, 1.5%, United Arab Emirates, 0.8%, Palestine, 2.2%, and Yemen, 2.6%.1 The prevalence of HCV in Saudi Arabia and the aforementioned countries is similar to the prevalence reported in industrialized countries.1 One notable exception is Egypt, in which the prevalence is known to be exceptionally high (up to 40% in some parts of Egypt), probably because of the use of non-disposable, non-sterilized syringes to administer tartar emetic in mass treatment campaigns to control schistosomiasis in the 1960s through 1980s.8–12

Previous studies in Saudi Arabia indicated that the anti-HCV prevalence was 0.4% to 1.7% for adults and 0.1% for children.13–16 For instance, a study in Jeddah among 528 blood donors showed an anti-HCV prevalence of 1.7%.13 In a large study among 557 813 Saudi subjects of all ages in Riyadh province, the anti-HCV prevalence was 1.1% for adults and 0.1% for children.14 A study among 24 173 blood donors in Riyadh province over a three-year period from January 2000 to December 2002 showed an anti-HCV prevalence of 0.4%.15 A recent study among 13 443 blood donors in the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia showed a decline in the prevalence of anti-HCV from 1.04% in 1998 to 0.59% in 2001.16 In the current study, the number of HCV infections reported in different regions of Saudi Arabia ranged from 33 to 9186 infections with a mean of 1247 infections per region. When expressed per population, these figures translate to a range of 0.016% to 0.322% and a mean of 0.124%. The number of infections reported among adults was 23 950 infections (0.202%) and that among children was 998 infections (0.012%). These figures do not necessarily reflect the actual prevalence of HCV because of the nature of the study design. The relatively low number of reported cases in this study was most likely due to underreporting. The number of cases slightly and steadily rose from 1998 to 2002 perhaps owing to improved reporting and/or population growth estimated to be 3.3% annually. From 2003 to 2005, the number of annually reported cases seemed to have plateaued (Figure 1).

In this study, the number of HCV infections reported among children (0.012%) was much lower than that among adults (0.202%). This suggests that perinatal and childhood transmission is not a major mode of infection. On the other hand, the predominance of this infection in adults suggests that the other modes of transmission such as unscreened blood transfusion before 1990 and intravenous drug use are the main modes of infection in Saudi Arabia. Substance abuse is an increasing problem in Saudi Arabia as it is in the rest of the world.17–21 Substances abused include injectable drugs such as heroin and cocaine and noninjectable drugs such as cannabis and amphetamine-type stimulants. The estimated annual prevalence of substance abuse in Saudi Arabia in 2000 as percentage of the population aged 15 and above was 0.01% for heroin and 0.002% for amphetamine.17 The number of drug abusers annually admitted to detoxification centers in Riyadh, Jeddah, Dammam, and Qassim from 1996 through 2001 ranged from 4740 to 6650 patients with an average annual increment of 5.1% (unpublished data). The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among 799 drug abusers from a voluntary detoxification unit in Jeddah was reported to be 69%.18 Thus, substance abuse seems to be a potential major risk factor for the spread of HCV among adults in Saudi Arabia.

The prevalence of HCV infection is lower than the prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) in Saudi Arabia. A recent study showed that the prevalence of HBV infection in Saudi Arabia was on average 0.15% with wide variations between various regions ranging from 0.03% to 0.72%.22 In that study, the prevalence of HBV among children was 0.05% and that among adults was 0.22%.

Since there is as yet no vaccine to prevent HCV infection, the strategy to prevent this infection in Saudi Arabia focuses mainly on health education, routine screening of blood and organ donors and high-risk subjects such as household and sexual contacts of HCV patients, hemodialysis patients, patients requiring recurrent blood transfusion, intravenous drug users, and patients with other sexually transmitted infections. Additionally, implementation and maintenance of proper infection control practice in health care settings, including standard precautions and proper sterilization of surgical and dental equipment, and good hygienic practice in barbershops and traditional therapy settings such as wet cupping (Hijama) are emphasized in Saudi Arabia.

This study has several limitations. The fact that the study was not a cross-sectional survey but rather a passive reporting of anti-HCV positive cases to the Ministry of Health obviously carried a risk of under- or perhaps over-estimation of the actual magnitude of HCV infection in Saudi Arabia. On the one hand, routine testing of low-risk groups (such as blood or organ donors and expatriates pre-employment) may underestimate the prevalence. On the other hand, testing high-risk groups (such as drug abusers, prisoners, contacts of HCV-infected patients, patients with other sexually transmitted infections) may overestimate the actual prevalence. Another limitation is that information (liver function, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma) was not reported to the Ministry of Health as this was not part of the notification information mandated by the Ministry of Health. Further, different screening and confirmatory assays were used by different health sectors (the Ministry of Health, the Universities, the National Guard, the Armed Forces, King Faisal Specialist, and the private hospitals).

In conclusion, the incidence of HCV infection in Saudi Arabia is low. In the absence of an HCV vaccine, efforts to prevent the spread of this infection should focus on ensuring safe blood, blood products, and organs for transplantation, ensuring safe use of syringes, needles, sharps, and other equipment used for medical or traditional percutaneous interventions, implementation and maintenance of proper infection control practice in health care settings, and health education particularly targeting high risk groups.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) Hepatitis C - global prevalence (update) Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 1999;74(49):421–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomson BJ, Finch RG. Hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11(2):86–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.01061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science. 1989;244:359–62. doi: 10.1126/science.2523562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Houghton M. Hepatitis C viruses. In: Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM, Chanock RM, Melnick JL, Monath TP, Roizman B, Straus SE, editors. Fields virology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1996. pp. 1035–58. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tahan V, Karaca C, Yildirim B, Bozbas A, Ozaras R, Demir K, Avsar E, Mert A, Besisik F, Kaymakoglu S, Senturk H, Cakaloglu Y, Kalayci C, Okten A, Tozun N. Sexual transmission of HCV between spouses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(4):821–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magder LS, Fix AD, Mikhail NN, Mohamed MK, Abdel-Hamid M, Abdel-Aziz F, Medhat A, Strickland GT. Estimation of the risk of transmission of hepatitis C between spouses in Egypt based on seroprevalence data. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(1):160–5. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohto H, Terazawa S, Sasaki N, Sasaki N, Hino K, Ishiwata C, Kako M, Ujiie N, Endo C, Matsui A, et al. Transmission of hepatitis C virus from mothers to infants. The Vertical Transmission of Hepatitis C Virus Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(11):744–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403173301103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darwish MA, Raouf TA, Rushdy P, Constantine NT, Rao MR, Edelman R. Risk factors associated with a high seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in Egyptian blood donors. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49(4):440–7. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.49.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darwish MA, Faris R, Clemens JD, Rao MR, Edelman R. High seroprevalence of hepatitis A, B, C, and E viruses in residents in an Egyptian village in The Nile Delta: a pilot study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54(6):554–8. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank C, Mohamed MK, Strickland GT, Lavanchy D, Arthur RR, Magder LS, El Khoby T, Abdel-Wahab Y, Aly Ohn ES, Anwar W, Sallam I. The role of parenteral antischistosomal therapy in the spread of hepatitis C virus in Egypt. Lancet. 2000;355(9207):887–91. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)06527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darwish MA, Faris R, Darwish N, Shouman A, Gadallah M, El-Sharkawy MS, Edelman R, Grumbach K, Rao MR, Clemens JD. Hepatitis C and cirrhotic liver disease in the Nile delta of Egypt: a community-based study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64(3–4):147–53. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao MR, Naficy AB, Darwish MA, Darwish NM, Schisterman E, Clemens JD, Edelman R. Further evidence for association of hepatitis C infection with parenteral schistosomiasis treatment in Egypt. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2002;2:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-2-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdelaal M, Rowbottom D, Zawawi T, Scott T, Gilpin C. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus: a study of male blood donors in Saudi Arabia. Transfusion. 1994;34(2):135–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1994.34294143941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shobokshi OA, Serebour FE, Al-Drees AZ, Mitwalli AH, Qahtani A, Skakni LI. Hepatitis C virus seroprevalence rate among Saudis. Saudi Med J. 2003;24(Suppl 2):S81–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Hazmi MM. Prevalence of HBV, HCV, HIV-1, 2 and HTLV-I/II infections among blood donors in a teaching hospital in the Central region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2004;25(1):26–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bashawri LA, Fawaz NA, Ahmad MS, Qadi AA, Almawi WY. Prevalence of seromarkers of HBV and HCV among blood donors in eastern Saudi Arabia, 1998–2001. Clin Lab Haematol. 2004;26(3):225–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2257.2004.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Global illicit drug trends 2003. Office on Drugs and Crime, United Nations; United Nations Publication Sales no. E.03.X1.5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iqbal N. Substance dependence. A hospital based survey. Saudi Med J. 2000;21(1):51–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Njoh J. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus markers among drug-dependent patients in Jeddah Saudi Arabia. East Afr Med J. 1995;72(8):490–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Njoh J, Zimmo S. Prevalence of antibody to hepatitis D virus among HBsAg-positive drug-dependent patients in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. East Afr Med J. 1998;75(6):327–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hafeiz HB. Socio-demographic correlates and pattern of drug abuse in eastern Saudi Arabia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;38(3):255–9. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)90001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madani TA. Trend in incidence of hepatitis B virus infection during a decade of universal childhood hepatitis B vaccination in Saudi Arabia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101(3):278–83. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]