Abstract

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches present strong opportunities to promote health equity by improving health within low-income communities and communities of color. CBPR principles and evaluation frameworks highlight an emphasis on equitable group dynamics (e.g., shared leadership and power, participatory decision-making, two-way open communication) that promote both equitable processes within partnerships and health equity in the communities with whom they engage. The development of an evaluation framework that describes the manner in which equitable group dynamics promote intermediate and long-term equity outcomes can aid partners in assessing their ability to work together effectively and improve health equity in the broader community. CBPR principles align with health equity evaluation guidelines recently developed for Health Impact Assessments (HIAs), which emphasize meaningful engagement of communities in decision-making processes that influence their health. In this paper, we propose a synergistic framework integrating contributions from CBPR and HIA evaluation frameworks in order to guide efforts to evaluate partnership effectiveness in addressing health inequities. We suggest specific indicators that might be used to assess partnership effectiveness in addressing health equity and discuss implications for evaluation of partnership approaches to address health equity.

1. Introduction

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a collaborative approach to research that involves members of communities, academic researchers, practitioners, organizational representatives, and others in all aspects of the research process (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2013; Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998). CBPR builds upon several approaches to collaborative research from multiple disciplines, including participatory research (deKoning & Martin, 1996), action research (Brown & Tandon, 1983), and participatory action research (Falsborda & Rahman, 1991). While a number of similar approaches have been developed, the term CBPR has been increasingly used over the last 20 years to describe participatory approaches to research and action in public health, nursing, social work, and related fields (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998; Wallerstein, Duran, Oetzel & Minkler, 2018). CBPR is situated within the broader field of community-engaged research, emphasizing collaborative partnerships between researchers and community partners to address health risk factors and social inequities by engaging community strengths (Wallerstein, Yen & Syme, 2011).

CBPR approaches in public health are rooted in principles of collaborative and equitable partnership in all phases of research, with all partners working together to identify mutual issues and to take action to address them. This includes a focus on: empowerment and power-sharing processes that attend to social inequalities; building on community strengths and resources; co-learning and capacity building among all partners; attending to the local relevance of public health problems; and ecological perspectives that address multiple determinants of health (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2013). CBPR’s emphases on social equity and the multiple determinants of health render it particularly appropriate for addressing poor health outcomes in low income communities and communities of color that result from the inequitable distribution of economic, political, environmental, and social resources.

Braveman and colleagues (2017) suggest that health equity is achieved when all have a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible. This requires removing obstacles to health (e.g., poverty, discrimination) and their consequences, including powerlessness and lack of access to fair-paying jobs, quality education, health care, and other factors. Braveman and colleagues note that, “For the purposes of measurement, health equity means reducing and ultimately eliminating disparities in health and its determinants that adversely affect excluded or marginalized groups” (Braveman, Arkin, Orleans, Proctor, & Plough, 2017, p. 2). Within a CBPR approach, the focus on equitable relationships and shared power among community, academic, and practice members of CBPR partnerships is central to the promotion of health equity. Health inequities that are grounded in imbalances of economic and social resources operate in part by excluding members of marginalized communities from the opportunity to influence decisions that affect their health and well-being. Those same processes can operate within partnerships, reproducing the very inequities that they are intending to address, and interfering with partners’ ability to work effectively together (Johnson & Johnson, 2017; Schulz, Krieger, & Galea, 2002). Thus, it is important for partnerships invested in equity to critically evaluate the extent to which they provide opportunities for meaningful participation and engagement of community members in decision-making processes (Schulz, Krieger, & Galea, 2002).

Effective evaluation of partnership efforts requires a clear conceptual framework that links group dynamic characteristics of equitable partnerships (e.g., shared leadership, meaningful participation, power sharing) with the effectiveness of partnership efforts to intervene to reduce health inequities more broadly. Complementing the literature on evaluating group dynamics within CBPR partnerships (Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013; Lantz, Viruell-Fuentes, Israel, Softley, & Guzman, 2001; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003; 2017) is an emergent literature from health impact assessment (HIA) practitioners, proposing dimensions that can be used to assess equity within the context of HIA processes. HIA is a systematic process that uses various data sources, analytic methods, and stakeholder input to assess the potential impacts of a proposed policy, plan, program, or project on the health of a population and the distribution of those impacts within the population (National Research Council Committee on Health Impact Assessment, 2011). HIA practice standards share principles of democracy and equity promotion in common with CBPR, pointing to synergies between these approaches that inform the development of an evaluation framework for equity promotion for CBPR partnerships and other forms of community-partnered and community-engaged research. In this paper, we: 1) examine contributions from both CBPR and HIA literatures; 2) propose a synergistic framework that integrates their contributions to evaluate partnership effectiveness in addressing health inequities; and 3) identify specific indicators that may be used to assess the effectiveness of partnerships in addressing health equity issues.

1.1 Frameworks for Equity Evaluation

1.2 Community-based participatory research partnership evaluation

CBPR partnership evaluation frameworks have encompassed a strong focus on evaluating group dynamics characteristics of the partnerships themselves, guided by literature linking partnership effectiveness in working together with the ability of the partnership to address identified health outcomes (Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003, 2017; Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013). Dimensions of interest within these evaluation frameworks include: 1) social and contextual conditions within which the partnership operates; 2) group dynamics characteristics which foster equity, such as open communication and shared power, decision-making, and leadership; 3) partnership programs and interventions; and 4) intermediate outcomes; and 5) long-term outcomes (e.g., changes in policy, systems, community capacity, and health that emerge from the partnership’s efforts) (Cacari-Stone, Wallerstein, Garcia, & Minkler, 2014; Kastelic et al., 2018; Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003; 2017). These frameworks, based on empirical evidence, emphasize the critical role of equitable group dynamics, in which goals are collaboratively identified, power is equalized and shared, and partners build mutual support and trust (Johnson & Johnson, 2017; Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003; 2017). These processes promote equitable engagement of all partners, improving partnership effectiveness in working together to reach mutually defined goals.

Schulz, Israel, and colleagues (Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003, 2017) developed a framework that suggests structural characteristics of partnerships, environmental characteristics, group dynamics characteristics, and partnership interventions and programs influence intermediate measures (e.g., perceived effectiveness of the group) and output measures of partnership effectiveness (e.g., achievement of program and policy objectives, institutionalization of programs). Drawing upon this and other work, Wallerstein and colleagues (2008) developed a conceptual model illustrating processes linking contextual, structural, individual, and relational dimensions of partnership group dynamics and interventions with changes in power relations and social and economic conditions, which are central to attaining reductions in health disparities. Cacari-Stone and colleagues (2014) demonstrate pathways through which contextual factors, CBPR processes (including partnership dynamics), and policymaking influence outcomes such as political action, procedural and distributive justice, and health outcomes. They argue that research evidence combined with civic engagement of groups facing the greatest burden of health impacts facilitates a shift in leadership and power to spur political action and policy to alleviate health inequities (Cacari-Stone, Wallerstein, Garcia, & Minkler, 2014).

Context

Existing frameworks within the CBPR literature link social and contextual factors to partnership dynamics and ultimately to the effectiveness of the partnership in promoting health equity (Cacari-Stone, Wallerstein, Garcia, & Minkler, 2014; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003; 2017; Kastelic et al., 2018; Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013). They are explicit in linking structural factors (e.g., social conditions, inequitable access to economic resources) to inequities that may exist within the context of partnership processes, programs and interventions, and outcomes. They explicitly draw attention to the importance of attending to the ways in which those inequities can be expressed within partnership group dynamics (Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003; 2017; Kastelic et al., 2018;). For example, under-resourced community groups may have less capacity to participate in partnership meetings, contributing to reduced influence in decisions.

Group Dynamics

In existing frameworks, equitable group dynamics are central to a partnership’s success in building relationships and establishing a culture of inclusion; thus, it is critical for partners to work effectively together to achieve their mutually identified goals. Equitable group dynamics are seen as the starting point for fostering equitable community engagement and working relationships, contributing to higher quality research and interventions, and ultimately, providing the foundation for achieving intermediate and long-term outcomes to promote health equity (e.g., community empowerment, program and policy changes) (Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003; 2017; Wallerstein, Oetzel, Duran, Tafoya, Belone, et al., 2008).

Partnership Programs and Interventions

CBPR frameworks emphasize the development of programs and interventions that reflect community priorities and integrate community knowledge and input (Kastelic et al., 2018; Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003; 2017). Meaningful involvement of community partners in these activities is facilitated by group dynamics that allow for community partners to provide input, knowledge, and resources to influence partnership programs and interventions. Involvement of community partners in research activities may also facilitate research designs and processes that are appropriate for local and cultural contexts and reflect community concerns (Kastelic et al., 2018; Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003; 2017). These activities may ultimately facilitate the development of programs that promote equitable intermediate and long-term outcomes.

Intermediate Outcomes

Effective group dynamics within partnerships, in addition to programs and interventions that empower communities and promote health, contribute to intermediate outcomes such as the extent of member involvement in partnership activities and a sense of shared ownership and commitment to collaborative work of the partnership (Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003; 2017; Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013). Intermediate processes also include changes in power relations within partnerships and improvements in individual and community capacity (e.g., knowledge, influence in decision-making processes), which contribute to the achievement of long-term partnership goals and objectives (Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013; Kastelic et al., 2018; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003; 2017).

Long-Term Outcomes

By improving power dynamics and building capacity for change, the intermediate processes described above can facilitate long-term outcomes such as changes in policy or practice, institutionalization of programs and interventions, and changes in health outcomes and health inequities (Kastelic et al., 2018; Schulz et al., 2003; 2017; Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013). In addition to health inequities, long-term outcomes also encompass community-level changes such as transformed social and economic conditions and increased social justice (Kastelic et al., 2018).

1.3 Health Impact Assessment equity evaluation

An emphasis on evaluation of equity has also emerged in recent health impact assessment (HIA) literature. The goal of an HIA is to proactively estimate potential effects prior to implementation of a policy, plan, program or project, and to offer recommendations that will mitigate or avoid adverse effects on health, maximize potential health benefits, and support health equity. The HIA process typically entails five stages of work in order to achieve this goal: Screening, Scoping, Assessment, Recommendations, Reporting, and Monitoring and Evaluation. In an effort to clearly distinguish HIA as a practice and to promote quality within the field, a working group was convened during a 2-day conference of the North American HIA Practice Standards Working Group in 2008 to develop minimum standards of practice. The standards, which were first published in 2009 and revised in 2014, were to be used as quality benchmarks and to facilitate discussion about the HIA process among practitioners (Bhatia, Farhang, Heller, Lee, Orenstein et al., 2014; North American HIA Practice Standards Working Group, 2009).

While CBPR has not traditionally developed formalized Practice Standards, such as those that have emerged within the HIA field, the guiding principles and practice standards described above share much in common with longstanding principles guiding CBPR (see Israel et al 2018). Principles of HIA include equity and democracy, with attention to engaging all stakeholders, including communities who may be affected by the decision in question, at each stage of the HIA process. In keeping with these core values, HIA practice standards emphasize the importance of: shared leadership, resources, power, and decision-making in conducting HIAs; addressing the distribution of health impacts within populations; and promoting stakeholder participation in transparent processes for policymaking (European Centre for Health Policy, 1999; Heller, Givens, Yuen, Gould, Jandu et al., 2014; North American HIA Practice Standards Working Group, 2009; Partidario & Sheate, 2013). Consistent with a CBPR approach, this includes an emphasis on the active role of marginalized groups in technical and decision-making processes from which they have been historically excluded (Corburn, 2003), meaningful engagement of communities in the HIA process, and recognizing and addressing institutional barriers to community participation in that process (Iroz-Elardo, 2014; Kearney, 2004). Additionally, HIA’s emphases on shared leadership, power, and decision-making among partners align with group dynamics characteristics described in the CBPR group process literature (described above) that facilitate equity within partnership processes.

Building on these principles, the Society of Practitioners of Health Impact Assessment (SOPHIA) developed Equity Metrics for Health Impact Assessment Practice in order to facilitate more intentional and systematic incorporation of equity promotion in HIA practice. Created to provide more detail to the HIA practice standards with respect to equity, the metrics are designed to help practitioners assess the extent to which an HIA has incorporated health equity considerations in planning and implementation (SOPHIA Equity Working Group, n.d.). The metrics span four dimensions of equity that can be evaluated to assess the extent to which equity is addressed within the context of an HIA. These include evaluating the extent to which the HIA: 1) focuses on equity in its process and products; 2) builds the capacity of communities facing health inequities to engage in future HIAs and decision-making; 3) results in a shift in power that benefits communities facing inequities; and 4) contributes to changes that reduce health inequities and inequities in the social and environmental determinants of health. (SOPHIA Equity Working Group, n.d; Heller, Givens, Yuen, Gould, Jandu et al., 2014). We briefly describe each of these dimensions of equity from the HIA literature below.

The first dimension, a focus on equity in HIA processes and products, includes: analysis of issues that are identified by and important to communities facing inequities; focus on equity in the goals, research questions, and methods used in conducting the HIA; responsiveness to community concerns; and incorporation of community knowledge, skills, and capacities in the HIA’s research and change efforts (Heller, Givens, Yuen, Gould, Jandu et al., 2014). The second dimension introduced by Heller and colleagues (2014) focuses on the extent to which the HIA builds the capacity and ability of communities facing health inequities to engage in future HIAs and decision-making, including knowledge and awareness of decision-making processes and the ability to plan, organize and fundraise within the decision-making context. The third dimension encompasses assessment of the extent to which the HIA results in a shift in power benefiting communities facing health inequities. Heller and colleagues (2014) describe this as a change in a community’s ability to influence decisions, policies, partnerships, institutions, or systems both within and beyond the scope of the HIA. The fourth and final dimension for evaluating equity within the context of HIAs focuses on health equity as an outcome. As described by Heller and colleagues (2014), this dimension encompasses assessment of the extent to which the HIA contributes to decreased differentials in social or physical determinants of health and/or reduced differentials in health outcomes between communities facing inequities and other communities (Heller, Givens, Yuen, Gould, Jandu et al., 2014).

2. Creating a Synergistic Framework for Evaluating Equitable Processes and Outcomes in CBPR Partnerships Integrating Health Equity Evaluation from HIA Literature

There are multiple synergies between the four dimensions of equity evaluation emerging from the HIA literature and conceptual frameworks in the CBPR literature linking characteristics of effective and equitable groups to CBPR partnership effectiveness described in the previous section. We examine these synergies with the goal of offering an integrated conceptual framework that links equity within the context of partnership group dynamics with intermediate impacts and long term equity outcomes. By more clearly specifying these processes and pathways, we aim to contribute to development of evaluation metrics that enable CBPR, HIA, and other partnership approaches to research to systematically examine their own process and implications for the impacts and outcomes of their work together, with the ultimate goal of strengthening partnerships’ efforts to promote health equity.

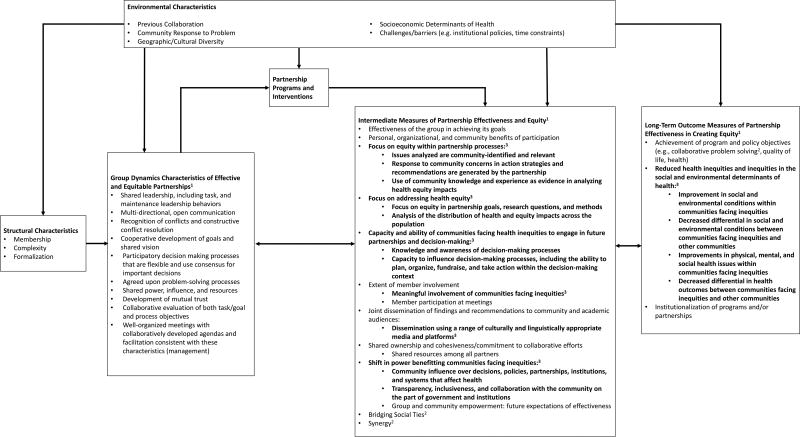

Figure 1 displays the integration of the four dimensions of health equity evaluation from the HIA literature described above with an existing conceptual framework for evaluating CBPR partnership dynamics (Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013; Schulz Israel, & Lantz, 2003, 2017). This synergistic framework adapts and extends previous work suggesting that a partnership’s ability to reach its long-term outcome objectives for effectiveness and equity is shaped by intermediate measures of partnership effectiveness and equity (Heller, Givens, Yuen, Gould, Jandu et al., 2014; Lasker & Weiss, 2003; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003, 2017; Sofaer, 2003). Working from left to right, we describe the major components of the model, and discuss the intermediate and long-term outcome measures that have been integrated into the model based on the equity dimensions described by Heller and colleagues (2014), providing the rationale and relevant literature supporting each dimension. Specifically, we focus our discussion on five equity dimensions in Figure 1: 1) a focus on equity in partnership processes; 2) a focus on addressing health equity; 3) capacity and ability of communities facing health inequities to engage in future partnerships and decision-making; 3) shift in power benefitting communities facing inequities; and 4) reductions in health inequities and inequities in the social and environmental determinants of health.

Figure 1.

- Based on Schulz, Israel, and Lantz (2003).

- Adapted from Schulz, Israel, and Lantz (2013, 2017).

- Bolded items are derived from Heller, Givens, Yuen, Gould, Jandu et al., (2014)

2.1 Group Dynamics Characteristics of Equitable Partnerships

As noted above, Figure 1 builds on earlier conceptual models that place group dynamics at the center of effective efforts to promote health equity (Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003; 2017). This model highlights group dynamics characteristics including shared leadership, two-way communication, and constructive conflict resolution that have been previously demonstrated to influence group effectiveness (Johnson & Johnson, 2017). Such processes focus on explicit strategies that promote equitable engagement and have been demonstrated to strengthen relationships, improve the quality of decision-making, promote group cohesion, and increase effective change (Johnson & Johnson, 2017). Formal structures that clearly delineate roles for partners and processes for working together can improve group dynamics within partnerships with a history of mistrust among those involved (e.g., tribal communities whose treaties with the U.S. government have been broken; communities that experience systematic disinvestment and exclusion from educational opportunities) (Wallerstein & Minkler 2008; Becker, Israel, Gustat, Reyes, & Allen, 2013; Yonas, Aronson, Coas, Eng, Petteway et al., 2013).

Figure 1 suggests that group dynamics are shaped by the structural characteristics of groups (e.g., membership, complexity) as well as historical and geographic contexts within which they exist. As one example, Wallerstein and colleagues (2008) suggest that more culturally diverse partnerships may face particular challenges with group dynamics associated with differences in interactional styles and historical patterns of intergroup relationships (e.g., colonization, class or racial hierarchies). As explained by Chavez and colleagues (2008) and Minkler (2004), historical trauma, institutionally and personally mediated racism, internalized oppression, and differences in priorities and reward structures for research can produce tensions between community partners and outside researchers. These tensions may lead to: fear of speaking up about oppression due to mistrust of researchers; deference to dominant group norms; and perpetuation of institutional and interpersonal racism (Chavez et al., 2008; Minkler, 2004). In addition, historically marginalized groups may hold competing agendas or compete for scarce resources, which can create tension or conflict amongst those groups within the context of partnerships. Partnership processes that promote cultural humility and strengthen a sense of collective identity may be particularly critical within such partnerships as they recognize potential tensions, engage in reflection and analysis of communication styles, and promote behaviors that alter the climate of the working environment (Kastelic et al., 2018; Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2013; Oetzel et al., 2017). Partnership-building activities that establish mutual trust, promote multi-directional communication, disperse power, resources, and decision-making among all partners, and promote cooperative development of goals and a shared vision (Becker, Israel, Gustat, Reyes, & Allen, 2013; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2017; 2003) can strengthen the ability of communities facing inequities to participate equitably in groups, influence decisions about priorities, interventions and research (Corburn, 2003; Heller, Givens, Yuen, Gould, Jandu et al., 2014).

2.3 Intermediate Measures of Partnership Effectiveness and Equity

As presented in Figure 1, the Group Dynamics Characteristics of Effective and Equitable Partnerships described above influence the nature of Partnership Programs and Interventions, which in turn impact Intermediate Measures of Partnership Effectiveness and Equity. Intermediate measures capture the extent to which equity is promoted within partnership processes as a result of these factors. Changes in these intermediate measures both reflect and affect partnership programs and interventions implemented throughout the life of the partnership. In accordance with Heller and colleagues’ HIA equity evaluation framework (Heller et al, 2014), we consider five major categories of intermediate indicators of partnership effectiveness and equity, conceptualized as the extent to which the partnership has the ability to influence identified equity outcomes. These are indicators of: 1) a focus on equity in partnership processes (e.g., equitable engagement); 2) a focus on addressing health equity; 3) capacity of communities facing inequities to participate in decision making; and 4) shifts in power to benefit communities facing inequities. We describe each of these below, and their implications for Long-term Outcome Measures discussed in the following section.

Focus on equity within partnership processes

Partnership-building activities that improve group dynamics and disperse power and leadership can promote more equitable partnership processes (Duran et al., 2013). As shown in Figure 1, equity promotion within partnerships includes outcomes such as the extent to which issues analyzed by the partnership are community-identified and relevant, and responsiveness of the partnership to community concerns in action strategies and recommendations. In addition, a focus on the use of community knowledge and experience as evidence in analyzing health and equity impacts can be indicative of a focus on addressing processes that reinforce inequities by delegitimizing community knowledge and experience (Heller, Givens, Yuen, Gould, Jandu et al., 2014). These factors promote equity within partnership processes and strengthen recommendations, programs and policy interventions by directly incorporating community insights, knowledge, and understanding. They also help to counteract potential impacts of power hierarchies that have historically privileged researchers and professionals in research decision-making processes, knowledge creation, and voice representation in data and publications (Muhammad, Wallerstein, Sussman, Avila, Belone & Duran, 2015). The three indicators named here have been incorporated in Figure 1 as intermediate outcomes, which are determined by both Group Dynamics Characteristics of Effective and Equitable Partnerships and Partnership Programs and Interventions. Partnership strategies and processes in working together, including effective and equitable group facilitation, shared power, and participatory decision-making can influence the extent to which partnership programs and interventions meaningfully engage communities facing inequities and incorporate their concerns, knowledge, and input in all activities (Corburn, 2006; Corburn, 2003; Iroz-Elardo, 2014; Israel, Schulz, Parker, Becker, Allen et al., 2008; Israel, Lichtenstein, Lantz, McGranaghan, Allen et al., 2001). By improving the partnership’s emphasis on equitable processes, Intermediate Measures of Partnership Effectiveness and Equity also have the potential to impact Group Dynamics Characteristics of Effective and Equitable Partnerships, such as participatory decision-making and development of mutual trust, indicated by the feedback arrow in Figure 1.

A focus on addressing health equity

Effective processes for working together can promote a focus on addressing health inequities through partnership programs and research. Heller and colleagues (2014) suggest that one primary goal of an HIA that advances health equity is to focus on equity impacts by clearly addressing equity in project goals, research questions, and methods. These aspects should promote a focus on addressing the social and environmental determinants of health inequities within communities. Furthermore, HIAs should assess the distribution of health and equity impacts across populations in order to measure disproportionate or cumulative impacts on communities facing inequities (Heller, Givens, Yuen, Gould, Jandu et al., 2014). Assessing these factors is aligned with CBPR’s long-term commitment to effectively reduce health inequities (Israel et al. 2018) and to develop research and interventions that influence the social determinants of health (Schulz, Kreiger, & Galea, 2002). As shown in Figure 1, equitable group dynamics and processes for working together can shape partnership CBPR programs and interventions, which influence the extent to which partners are addressing disparate health and social impacts between communities facing inequities and other communities through partnership activities. Group dynamics characteristics such as shared leadership and participatory decision-making may also promote analysis of disproportionate health impacts by incorporating underrepresented community voices into research and analysis processes (Corburn, 2003). Figure 1 incorporates two metrics to evaluate a partnership’s focus on addressing health equity: a focus on equity in partnership goals, research questions, and methods; and analysis of the distribution of health and equity impacts across the population.

Capacity and ability of communities facing health inequities to engage in future partnerships and decision-making

Heller and colleagues (2014) suggest that building the capacity of communities facing inequities involves meaningfully engaging representatives from those communities in examinations of power, policy, and historical context of decisions that affect their health. This idea is synergistic with CBPR conceptual frameworks that emphasize the role of equitable group dynamics that promote a shared understanding of power dynamics and historical processes (Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003, 2017; Wallerstein, Oetzel, Duran, Tafoya, Belone, et al., 2008). It is important for CBPR partnerships to assess how these efforts promote such a shared understanding in order to strengthen the capacity of marginalized communities to engage in future decision making and change efforts.

As shown in Figure 1, Group Dynamics Characteristics of Effective and Equitable Partnerships can influence the capacity of communities facing inequities through Partnership Programs and Interventions. Group characteristics such as shared leadership roles, participatory and consensus-based decision-making processes, and collaboratively developed and facilitated meeting structures are precursors to the development of programs and interventions that build the individual and collective capacity of the group (Becker, Israel, Gustat, Reyes, and Allen, 2013; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003, 2017; Yonas, Aronson, Coas, Eng, Petteway et al., 2013). Because these characteristics facilitate mutual goals and co-learning processes that equitably engage all partners, those who typically assume decision-making and leadership roles (e.g., academic partners, social institutions) must also learn to share power with other partners (Johnson & Johnson, 2017). Shared power and decision-making can promote meaningful involvement of community partners in all processes, prepare partners to take positions of leadership, and contribute to informed decision-making that will impact the community in the future. Specifically, communities facing inequities may contribute invaluable knowledge and awareness of decision-making processes while simultaneously increasing capacity to influence them, including the ability to plan, organize, and take action within the decision-making context (Heller, Givens, Yuen, Gould, Jandu et al., 2014). Simultaneously, those who more often assume leadership roles and decision making power may become more effective in sharing power and learning from the knowledge and insights of other partners (Johnson & Johnson, 2017). As indicated by the feedback arrows in Figure 1, improvements in these Intermediate Measures of Partnership Effectiveness and Equity may lead to further improvements in Group Dynamics Characteristics of Effective and Equitable Partnerships by strengthening leadership and resource capacities among members of communities facing inequities. In a cyclical process, these improved group characteristics may further improve Partnership Programs and Interventions.

Shift in power to benefit communities facing inequities

Partnership dynamics and capacities contribute to the ability of historically marginalized communities to organize, take action, and engage in decision-making on issues that affect their health. CBPR literature explicitly emphasizes the importance of group dynamics processes in which those from more privileged social and economic backgrounds learn to share decision making power, and to recognize the contributions and leadership capacities of those who often have been marginalized (Duran, Wallerstein, Avila, Minkler, Belone et al., 2013; Chavez, Duran, Baker, Avila, & Wallerstein, 2008), a point which Heller and colleagues reiterate in their emphasis on shifting power in ways that benefit marginalized communities that experience excess health risk (Heller et al., 2014). Through shared power and co-production of knowledge, equitable group dynamics can shift power by incorporating and legitimizing community knowledge and expertise, and facilitating community member participation in decision-making processes (Corburn 2003; Corburn, 2006; Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013; O’Fairchealliagh, 2010; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003, 2017). Thus, shared power and other equitable group dynamics work to shift power to benefit communities facing inequities both directly and by shaping Partnership Programs and Interventions, as shown in Figure 1. Programs and interventions may be implemented in ways that prioritize the voice of communities facing inequities, contributing to a shift in power benefiting those communities. For example, such efforts might help to better integrate community members or community-based organizations into formal policy and decision-making processes from which they are typically excluded (Heller, Givens, Yuen, Gould, Jandu et al., 2014). Heller and colleagues (2014) describe shifts in power as changes in a community’s ability to influence decisions, policies, partnerships, institutions, or systems, including but not limited to the specific decision of interest at the time, which can result from both equitable Group Dynamics Characteristics and Partnership Programs and Interventions. In addition, government and institutions may be more transparent, responsive, and collaborative with communities in the future (Heller, Givens, Yuen, Gould, Jandu et al., 2014; Duran et al., 2013; Chavez, Avila, Baker, Duran, & Wallerstein, 2008; Minkler, 2010). We have incorporated these metrics as Intermediate Measures of Partnership Effectiveness and Equity in Figure 1, along with other indicators of group and community empowerment measures (see Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013; Schulz, Israel, and Lantz, 2003, 2017).

2.4 Long-term Outcome Measures of Partnership Effectiveness and Health Equity

Reductions in health inequities and inequities in the social and environmental determinants of health

Figure 1 suggests that by creating dynamics that shift power in favor of marginalized communities, effective groups can also reduce inequities in the social and environmental determinants of health, achieving long-term health equity outcomes (Cacari-Stone, Wallerstein, Garcia, & Minkler, 2014; Wallerstein & Duran, 2010; Kastelic et al., 2018; Oetzel et al., 2018; Corburn, 2003; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003, 2017). As groups more equitably engage with and strengthen the power of marginalized communities in spaces and processes from which they are typically excluded (Corburn, 2003), they have the potential to more effectively influence policy and systems changes that affect health. Kastelic and colleagues (2018) and others propose that within CBPR partnerships, both system and capacity changes and improved health outcomes can be linked with better group dynamics and the integration of local beliefs into research (Oetzel et al., 2018). These long-term outcomes resonate with outcome indicators suggested by Heller and colleagues (2014), focusing on assessing the extent to which the partnership impacts inequities in health outcomes and the social and environmental determinants that contribute to health inequities (Heller, Givens, Yuen, Gould, Jandu et al., 2014). These outcome indicators allow partnerships to assess the extent to which they are successful in reducing health inequities, while simultaneously conceptualizing those outcomes as products of both partnership dynamics and the programs and interventions that emerge from the partnership’s efforts.

3. Discussion

In this paper, we examine contributions from CBPR evaluation and HIA equity promotion frameworks in order to understand the role of partnership dynamics in creating equitable partnerships and developing interventions that shift power and foster more equitable health outcomes. We propose a synergistic framework that integrates contributions from CBPR and HIA frameworks to guide the evaluation of partnership effectiveness in addressing health inequities, and describe specific potential indicators for evaluation. As shown in Figure 1, we have integrated three sets of Intermediate and one set of Long-term Outcome Measures of Partnership Effectiveness and Equity based on the four dimensions of health equity described by Heller and colleagues (2014) and insights from existing CBPR conceptual frameworks described above. In this section, we discuss the use of a formative evaluation approach and potential metrics, data collection methods, and existing instruments to assess each integrated dimension.

3.1 Implications for Evaluation Approach

CBPR’s emphasis on cyclical and iterative processes of partnership development highlight the importance of formative evaluation approaches that allow partners to use data about partnership functioning to make improvements (Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013; Schulz, Israel & Lantz, 2003, 2017). Feeding back information obtained from evaluation of intermediate outcome measures helps partners to reflect on and integrate findings into efforts to improve health equity promotion and other dimensions of partnership effectiveness. Evaluators can use a variety of data collection methods—quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods such as surveys, interviews, focus groups, project documentation, and qualitative field notes, at multiple time points during the partnership to determine how well partners are working together and the extent to which they are achieving health equity goals (Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013; Wallerstein, Oetzel, Duran, Tafoya, Belone, et al., 2008; Creswell, 2013). Table 1 indicates potential data collection methods for each equity evaluation metric discussed here, along with specific indicators that may be used to assess each metric. In keeping with the focus on equity, we suggest that metrics to evaluate equity in partnership processes and outcomes be generated and agreed upon within the partnership and driven by community priorities (see Schulz, Israel, Lantz 2017 for example).

Table 1.

Health Equity Metrics and Data Collection Methods

| Health Equity Metric | Indicators | Data Collection Methods |

|---|---|---|

| A focus on equity within partnership processes | ||

|

| ||

| Issues analyzed are community-identified and relevant | Partnership Activities:

|

Document Review, e.g., Meeting Minutes |

| Partnership Evaluation Questionnaire1 | ||

|

| ||

| Response to community concerns in action strategies and recommendations are generated by the partnership |

|

Document Review |

| Field Notes | ||

| In-depth interviews | ||

|

| ||

| Use of community knowledge and experience as evidence in analyzing health equity impacts |

|

Document Review |

| Field Notes | ||

| In-depth interviews | ||

|

| ||

| A focus on addressing health equity | ||

|

| ||

| Focus on equity in partnership goals, research questions, and methods |

|

Document Review |

|

| ||

| Analysis of the distribution of health and equity impacts across the population |

|

Document Review |

| Literature Review | ||

|

| ||

| Capacity and ability of communities facing health inequities to engage in future partnerships and decision-making | ||

|

| ||

| Knowledge and awareness of decision-making processes |

|

Document Review |

| Partnership Evaluation Questionnaire | ||

|

| ||

| Capacity to influence decision-making processes, including the ability to plan, organize, fundraise, and take action within the decision-making context |

|

Document Review |

| Partnership Evaluation Questionnaire | ||

|

| ||

| A shift in power benefitting communities facing inequities | ||

|

| ||

| Community influence over decisions, policies, partnerships, institutions, and systems that affect health |

|

Document Review |

| Partnership Evaluation Questionnaire | ||

| In-depth interviews | ||

|

| ||

| Transparency, inclusiveness, and collaboration with the community on the part of governments and institutions |

|

Document Review, e.g., Legislative Briefings |

| Partnership Evaluation Questionnaire | ||

|

| ||

| Reduced health inequities and inequities in the social and environmental determinants of health | ||

|

| ||

| Improvement in social and environmental conditions within communities facing inequities |

|

Document Review |

| Partnership Evaluation Questionnaire | ||

|

| ||

| Decreased differential in social and environmental conditions between communities facing inequities and other communities |

|

Document Review, e.g., public reports |

| Partnership Evaluation Questionnaire | ||

|

| ||

| Improvements in physical, mental, and social health issues within communities facing inequities |

|

Document Review e.g., morbidity and mortality reports, health status measures |

|

| ||

| Decreased differential in health outcomes between communities facing health inequities and other communities |

|

Document Review e.g., morbidity and mortality reports, health status measures |

For examples of survey instruments, please see the following resources: http://cpr.unm.edu/research-projects/cbpr-project/cbpr-model.html https://www.detroiturc.org/resources/urc-cbpr-tools.html

Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, P. (2017). Assessing and strengthening characteristics of effective groups in community-based participatory research partnerships. In Garvin, C.D., Gutierrez, L.M., & Galinsky, M.J. (Eds). Handbook of Social Work with Groups, 2nd ed. Guilford Publications.

Wallerstein, N. (2018). Appendix 10: Instruments and measures for evaluating community engagement partnerships. In Wallerstein, N., Duran, B., Oetzel, J., Minkler, M. (Eds.) Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing Social and Health Equity, 3rd ed. (pp. 393–397). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass

Partnership evaluation should also consider carefully the time periods for collection of data on the Intermediate and Long-term Outcome Measures of Partnership Effectiveness and Equity. Intermediate measures can likely be assessed at multiple times over the course of the partnership, to be fed back and incorporated into efforts to improve the partnership. While partnerships may be able to assess some long-term outcome measures during the life of the partnership, contingent upon the time that the partnership works together, changes in health inequities and in the social and environmental conditions in communities may be visible, or may occur at a later point in time. Thus, consideration of intermediate indicators becomes particularly important.

3.2 Data collection methods and instruments

A focus on equity in partnership processes

As depicted in Table 1, in order to assess metrics related to equity promotion within partnership processes, partnerships might analyze project documentation, qualitative field notes, and questionnaire data. Metrics to evaluate equity within partnership processes may include responsiveness of community concerns in action strategies and recommendations generated by the partnership and the use of community knowledge and experience as evidence in analyzing health and equity impacts. Such items might be assessed using qualitative field notes and survey items capturing the extent to which communities facing inequities help to inform partnership activities. Instruments developed to assess decision-making procedures (Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003; 2017), and partnership alignment with community principles and interests (Brown & Vega, 2002) may be helpful for assessing these measures. To determine the extent to which issues analyzed by the partnership are community-identified and relevant, partners might review grant proposals to consider whether the proposal is informed by communities facing inequity, has support from the community, and is informed by the power, political, and historical context of the health problem. All of these measures discussed above, as well as other indicators may be generated through conversations within the partnership, again with an emphasis on reflecting community priorities.

A focus on addressing health equity

Measures assessing a focus on health equity in the community include addressing equity in partnership goals, research questions, and methods, and analysis of the distribution of health and equity impacts across the population (see Table 1). To assess the extent to which there is a focus on equity in partnership goals, research questions, and methods, partners can jointly identify potential indicators, review documents such as research proposals and meeting minutes to consider whether equity promotion is weighed in the formulation of these three elements, and whether the processes and criteria used to develop them reflect a focus on equity. Questionnaires completed by partnership members can also be used to assess partnership dynamics and members’ assessment of equity indicators (e.g., the extent to which partners agree that the goals of the partnership and its research activities reflect a focus on health equity, or that partnership activities consider impacts to communities facing inequity). Instruments assessing community inclusion and involvement in defining research objectives (Brown & Vega, 2002; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2017) may be used to evaluate these measures. Qualitative field notes taken during meetings can help to capture both group dynamics characteristics and the extent to which equity is an explicit consideration as partners collaborate to develop partnership programs and interventions. To determine the extent to which partners analyze the distribution of health and equity impacts across populations, partnerships may review project proposals, needs assessments, and published research produced by the partnership that investigate disproportionate or cumulative health impacts on communities facing inequities.

Capacity and ability of communities facing health inequities to engage in future partnerships and decision-making

As presented in Table 1, metrics to assess this measure are knowledge and awareness of the decision-making process, and the capacity to influence decision-making processes (e.g., planning, organizing, fundraising, taking action) (Heller, Givens, Yuen, Gould, Jandu et al., 2014). Partnerships might assess these measures using project documentation and/or partnership questionnaires. Specifically, partners may record and track instances in which community members: lead or serve on committees; provide input, expertise, and resources; improve awareness of health issues; and gain skills in research, advocacy, or community organizing. Documentation from trainings intended to build partners’ skills in health literacy, policy advocacy, systems change, and other topics can be used to assess changes in knowledge and awareness of decision-making processes, as can pre- and post-assessments of specific indicators of capacity completed by participants (Cheezum, Coombe, Israel, McGranaghan, Burris et al., 2013). Survey questionnaires may also assess changes in capacity to influence decision-making processes (Becker, Israel, Gustat, Reyes, & Allen, 2013), including community member knowledge, self-efficacy and behavioral intentions to engage in policy advocacy and other activities (Israel, Coombe, Cheezum, Schulz, McGranaghan et al., 2010). These skills and capacities may be developed in the context of partnership efforts to promote health equity, and may also extend to promote more equitable decision making in other arenas.

A shift in power benefitting communities facing inequities

Shifts in power can be measured by group and community empowerment, characterized by the influence of individuals, groups, and communities over decisions, policies, partnerships, institutions, and systems that affect the community and their health (see Table 1). Additional metrics can be identified by partnerships themselves, reflecting local contexts and values (Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2017). Partnerships can assess these measures through various forms of project documentation and questionnaires completed by partners and/or community residents. To measure community influence over decision-making, partners can record, for example, the number of times community member input is solicited by key decision-makers and the media, the number of times community members are asked to speak or testify at public hearings, or grants and other funds received by the group to further its work (Schriner & Fawcett, 1988). More specifically, shifts in power may be indicated by changes such as an increase in grants received in which community-based organizations or other community entities are the fiduciaries and play key leadership roles. As suggested in Table 1, partnership questionnaire items may also assess partner perceptions of the extent to which they are able to participate in decision-making that impacts their health. There are several examples of questionnaires in the CBPR literature which attempt to measure group and community empowerment or decision-making power in a variety of venues (Becker, Israel, Gustat, Reyes, & Allen, 2013; Israel, Checkoway, Schulz, & Zimmerman, 1994; Oetzel, Duran, Sussman, Pearson, Magarati et al., 2018; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2017, 2003).

Reduced health inequities and inequities in the social and environmental determinants of health

Changes in health inequities and the social and environmental determinants of health, presented as Long-term Outcome Measures of Partnership Effectiveness and Equity in Figure 1, can be measured by assessing changes in the social and environmental conditions within communities with disproportionate health risks between communities facing inequities and other communities (see Table 1). Project documentation, questionnaires, and review of morbidity and mortality reports and other measures of health status can be used to assess these measures. For example, partners can track and evaluate government and corporate response to community concerns over time, as well as the number and types of contact, meetings, and follow-up that community members have with policymakers (Schriner & Fawcett 1988). Partners can review morbidity and mortality reports from local governments (e.g., county health departments) to document and assess changes in relevant health issues and health outcomes. Pre- and post- survey questionnaire items might also be used to assess partners’ perceptions of these changes, as well as their perceptions of the extent to which the partnership has been effective in achieving specific goals, such as raising awareness or engaging community members and policymakers around strategies to reduce adverse health impacts (Becker, Israel, Gustat, Reyes, and Allen, 2013; Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003; 2017).

4. Conclusion and Lessons Learned

Bridging equity evaluation literature from CBPR and HIA has strong implications for evaluation of the intermediate and long-term impacts of CBPR partnerships and other partnerships focused on achieving health equity. CBPR evaluation frameworks demonstrate that effective and equitable group dynamics characteristics are critical to a partnership’s success in working together (Schulz, Israel, & Lantz, 2003; 2017; Wallerstein & Duran, 2010; Israel, Lantz, McGranaghan, Guzman, Lichtenstein et al. 2013; Kastelic et al., 2018). This paper extends that work through a synergistic framework that explicates equity within group dynamics as it contributes to a group’s effectiveness in addressing health equity, and suggests specific domains and methods for assessment of equity across levels of the conceptual framework. Integrating dimensions of health equity from HIA links group dynamics characteristics to specific equity outcomes to guide evaluation efforts within partnership efforts to achieve equity. These dimensions help to illuminate the link between equitable group dynamics and equitable outcomes within the partnership and in communities more broadly. Such frameworks may also benefit equity evaluation in other fields by incorporating consideration of the group dynamics characteristics that facilitate meaningful participation and influence of communities facing health inequities.

References

- Becker AB, Israel BA, Gustat J, Reyes AG, Allen AJ. Strategies and techniques for effective group process in CBPR partnerships. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Book. San-Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia R, Farhang L, Heller J, Lee M, Orenstein M, Richardson M, Wernham A. Minimum Elements and Practice Standards for Health Impact Assessment, Version 3 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Bond MH, Ng IW-C. The depth of a group’s personality resources: Impacts on group process and group performance. Asian Journal of Social Psychology. 2004;7:285–300. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P, Arkin E, Orleans T, Proctor D, Plough A. What is health equity? And what differences does a definition make? Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brown LD, Tandon R. Ideology and political economy in inquiry: Action research and participatory research. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 1983;19(3):277–294. [Google Scholar]

- Brown L, Vega W. A protocol for community-based research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1996;12(4 Suppl):4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfoss FD. Process evaluation for community participation. Annual Review of Public Health. 2006;27:323–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacari-Stone L, Wallerstein N, Garcia AP, Minkler M. The promise of community-based participatory research for health equity: a conceptual model for bridging evidence with policy. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(9):1615–1623. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez V, Duran B, Baker QE, Avila MM, Wallerstein N. The dance of race and privilege in CBPR. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research: from process to outcomes. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Cheezum RR, Coombe CM, Israel BA, McGranaghan RJ, Burris AN, Grant-White S, Weigl A, Anderson M. Building community capacity to advocate for policy change: An outcome evaluation of the Neighborhoods Working in Partnership project in Detroit. Journal of Community Practice. 2013;21(3):228–247. [Google Scholar]

- Corburn J. Bringing local knowledge into environmental decision-making: improving urban planning for communities at risk. Journal of Planning Education and Research. 2003;22:422–433. [Google Scholar]

- Corburn J. Street Science: Community Knowledge and Environmental Health Justice. Department of City and Regional Planning University of California, Berkeley. 2006;19:210. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- DeKoning K, Martin M, editors. Participatory research in health: Issues and experiences. London: Zed Books; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Duran B, Wallerstein N, Avila M, Belone L, Minkler M, Foley K. Developing and maintaining partnerships with communities. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. 2. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2013. pp. 41–68. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Health Policy. Health Impact Assessment: Main concepts and suggested approach (Gothenburg Consensus) Brussels: European Centre for Health Policy; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Borda O, Rahman MA, editors. Action and knowledge: Breaking the monopoly with participatory action research. New York: Apex Press; 1991. p. 182. [Google Scholar]

- Garvin CD, Gutiérrez LM, Galinsky MJ, editors. Handbook of social work with groups. Guilford Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Heller J, Givens ML, Yuen TK, Gould S, Jandu MB, Bourcier E, Choi T. Advancing efforts to achieve health equity: equity metrics for health impact assessment practice. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2014;11(11):11054–11064. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111111054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iroz-Elardo N. Health impact assessment as community participation. Community Development Journal. 2015;50(2):280–295. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Checkoway B, Schulz A, Zimmerman M. Health education and community empowerment: conceptualizing and measuring perceptions of individual, organizational, and community control. Health education quarterly. 1994;21(2):149–170. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, Schulz AJ, McGranaghan RJ, Lichtenstein R, Reyes AG, Clement J, Burris A. Community-based participatory research: a capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. American journal of public health. 2010;100(11):2094–2102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. 2. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Israel Lantz PM, McGranaghan RJ, Guzman JR, Lichtenstein R, Rowe Z. Documentation and evaluation of CBPT partnerships: The use of in-depth interviews and closed-ended questionnaires. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. 2. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2013. pp. 369–398. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Lichtenstein R, Lantz P, McGranaghan R, Allen A, Guzman JR, Softley D, Maciak B. The Detroit community-academic urban research center: development, implementation, and evaluation. Journal of public health management and practice: JPHMP. 2001;7(5):1–19. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200107050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen A, Guzman JR, Wallerstein N. Critical issues in developing and following community-based participatory research principles. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity. 3. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2018. pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual review of public health. 1998;19(1):173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DW, Johnson FP. Joining together: Group theory and group skills. 12. Pearson; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney M. Walking the walk? Community participation in HIA: a qualitative interview study. Environmental Impact Assessment Review. 2004;24:217–229. [Google Scholar]

- LaBonte R. Community, community development and the forming of authentic partnerships: some critical reflections. In: Minkler M, editor. Community Organizing and Community Building for Health. 2. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Univ. Press; 2005. p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- Lantz PM, Viruell-Fuentes E, Israel BA, Softley D, Guzman R. Can communities and academia work together on public health research? Evaluation results from a community-based participatory research partnershipin detroit. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78(3):495–507. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasker RD, Weiss ES. Broadening participation in community problem solving: a multidisciplinary model to support collaborative practice and research. Journal of Urban Health. 2003;80(1):14–47. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Linking science and policy through community-based participatory research to study and address health disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S81–S87. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.165720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-based participatory research: from process to outcomes. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad M, Wallerstein N, Sussman AL, Avila M, Belone L, Duran B. Reflections on researcher identity and power: The Impact of positionality on community based participatory research (CBPR) processes and outcomes. Critical Sociology. 2014;1:19. doi: 10.1177/0896920513516025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North American HIA Practice Standards Working Group. Practice standards for health impact assessment (HIA), version 1. Oakland (CA): North American HIA Practice Standards Working Group; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- O’Faircheallaigh C. Public participation and environmental impact assessment: purposes, implications, and lessons for public policy making. Environmental Impact Assessment Review. 2010;30:19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Oetzel J, Duran B, Sussman A, Pearson A, Magarati M, Khodakov D, Wallerstein N. Evaluation of CBPR partnerships and outcomes: Lessons and tools from the research for improved health study. In: Wallersten N, Duran B, Oetzel J, Minkler M, editors. Community-based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity. 3. 2018. pp. 237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Oetzel J, Wallerstein N, Duran B, Villegas M, Sanchez-Youngman S, Nguyen T, et al. Impact of Participatory Health Research: A Test of the Community-based Participatory Research Conceptual Model. International Journal of Public Health. 2017 doi: 10.1155/2018/7281405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partidario MR, Sheate WR. Knowledge brokerage - potential for increased capacities and shared power in impact assessment. Environmental Impact Assessment Review. 2013;39:26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Povall SL, Haigh FA, Abrahams D, Scott-Samuel A. Health equity impact assessment. Health Promotion International. 2014;29(4) doi: 10.1093/heapro/dat012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schriner KF, Fawcett SB. Development and validation of a community concerns report method. Journal of Community Psychology. 1988;16(3):306–316. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Lantz P. Instrument for evaluating dimensions of group dynamics within community-based participatory research partnerships. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2003;26(3):249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2018.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz Israel, Lantz P. Assessing and Strengthening Characteristics of Effective Groups in Community-Based Participatory Research Partnerships. In: Garvin CD, Gutierrez LM, Galinsky MJ, editors. Handbook of Social Work with Groups. 2. Guilford Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Krieger J, Galea S. Addressing social determinants of health: community-based participatory approaches to research and practice. 2002 doi: 10.1177/109019810202900302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOPHIA Equity Working Group. Equity Metrics for Health Impact Assessment Practice, Version 1. (n.d.). Retrieved from: http://www.hiasociety.org/documents/EquityMetrics_FINAL.pdf.

- Sofaer S. Working together, moving ahead. New York: Baruch College School of Public Affairs; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stakeholder Participation Working Group. ‘Guidance and best practices for stakeholder participation in health impact assessments’, 2010. HIA in the Americas Workshop; Oakland, CA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, Tafoya G, Belone L, Rae R. What predicts outcomes in CBPR. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Processes to Outcomes. Vol. 371388. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein NB, Yen IH, Syme SL. Integration of social epidemiology and community-engaged interventions to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(5):822–830. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonas M, Aronson R, Coad N, Eng E, Petteway R, Schaal J, Webb L. Infrastructure for equitable decision-making in research. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. 2. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2013. pp. 97–126. [Google Scholar]