Abstract

In high prevalence environments relationship characteristics are likely to be associated with HIV risk, yet evidence indicates general risk underestimation. Furthermore uncertainty about partner's risk may challenge PrEP demand among young African women. We conducted quantitative and qualitative interviews with women before and after HIV discussions with partners, to explore how partner's behavior affected risk perceptions and interest in PrEP. Twenty-three women were interviewed once; twelve had a follow-up interview after speaking to their partners. Fourteen women were willing to have their partner contacted; two men participated. Several themes related to relationships and risk were identified. These highlighted that young women’s romantic feelings and expectations influenced perceptions of risk within relationships, consistent with the concept of motivated reasoning. Findings emphasize challenges in using risk to promote HIV prevention among young women. Framing PrEP in a positive empowering way that avoids linking it to relationship risk may ultimately encourage greater uptake.

Keywords: HIV risk, HIV prevention, female-initiated methods, Pre-exposure prophylaxis

Introduction

The roll-out of oral HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in South Africa has begun, with an initial focus on female sex workers. In 2015, South Africa's national regulatory committee, the Medicines Control Council, approved the use of daily Truvada© for PrEP (1). Recommendations from global bodies such as the World Health Organization and the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) suggest offering PrEP for people at ‘substantial’ HIV risk, operationalized as 3% annual HIV incidence (2, 3). Given resource-related constraints, decisions will need to be made regarding who and how to rollout this new prevention method to at-risk populations.

PEPFAR has included PrEP as one part of a comprehensive HIV prevention program for young women (ages 15-24) for 10 priority countries in the DREAMS initiative (2). HIV incidence is 5-6% among young women in southern and East Africa in recent HIV prevention trials (4-6), supporting this population is as being at high HIV risk and thus in need of expanded prevention options (7, 8). In South Africa, approximately a quarter of all recent HIV infections among people 15-24 were among women and nearly four times as many young women are living with HIV than young men (9).

Numerous relationship level factors contribute to young women's increased susceptibility to HIV, among them inequitable gender norms that legitimize male sexual infidelity, encourage intergenerational relationships, and limit women's ability to negotiate safer sex, including male condom use (9-11). These factors may also limit women's use of oral PrEP. Qualitative research during the PrEP placebo-controlled effectiveness trials – and thus before women knew about PrEP efficacy – indicated that women's underestimation of risk, uncertainty of male partner's HIV status, and concerns around stigma and partner's reactions to product use contributed to low PrEP adherence (12-14). Understanding young women's risk tolerance and perceptions of risk of HIV are especially important given evidence that they do not have fully developed neurodevelopmental capacities until well into early adulthood, thereby affecting both their risk perception and decision-making (15-17). Furthermore, whereas HIV communication has traditionally assumed that individuals process and make inferences about the risks of potential partners in a rational, considered manner (15), substantial evidence from psychology suggests that beliefs are colored by motivations, desires and past experiences (18). Understanding the extent to which individuals engage in this kind of “motivated reasoning” may provide guidance about how effective communication strategies that assume rational perceptions of risk will be.

Now that high effectiveness of oral PrEP has been demonstrated in the context of high adherence, real world understanding (i.e. outside of the clinical trial setting) of facilitators of oral PrEP demand and use among young women is critical. Given that women's perceptions of risk may not match the reality of their risk within relationships, we sought to understand both how young women's relationships put them at risk and how this relates to the formation of their risk perception. Using a novel combination of qualitative and quantitative interdisciplinary methods, including behavioral survey questions, narrative vignettes, and in-depth interviews (IDIs) before and after they were encouraged to discuss HIV with male partners, we examined women's relationship context and risk perception.

Methods

Research Setting and Study Participants

This formative qualitative research study was conducted at the Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation (DTHF) research clinic just outside of Masiphumelele, Cape Town, South Africa. Masiphumelele is a predominantly Xhosa speaking township of 22,000 people located approximately 40km south of Cape Town city center. In 2008, at the time of the last household cross-sectional survey that included HIV testing, this community had an overall adult HIV prevalence of 25% (19).

The two participant groups included in this study were young PrEP inexperienced, HIV-negative women, ages 16-25, who were currently in sexual relationship(s) with a man of unknown or HIV-negative status, as well as their male partners. Young women participated in up to two IDIs and male partners participated in a single IDI. A purposive sample of female participants were recruited by community liaison officers, who approached females outside of schools, health clinics, and other community gathering spots, such as local shops, and preliminarily screened them for eligibility criteria (e.g. age, sexual relationship status, prior PrEP experience). Male partners were recruited upon approval for permission to contact from female participants in the study.

Data Collection

Data collection took place over a period of four months, from September 2015 to January 2016. During this time period, the community experienced civil unrest, which resulted in several protests that led to the closure of the community to all visitors (20).

All participants completed a quantitative questionnaire and an IDI and all female participants underwent an HIV test as part of study screening procedures. Three attempts were made to bring potential participants in for interviews, including for follow-up interviews with women. After three unsuccessful attempts, individuals were no longer considered for participation.

Women's relationships and sexual behaviors were examined using two approaches: 1) quantitative questions categorizing their past and current sexual relationships (i.e. number of partners, length of current relationship, age of partner, fidelity, Sexual Relationship and Power Scale (SRPS)) and 2) IDIs covering past and present relationships, sexual power, sexual behaviors, communication and decision-making, and HIV testing. Women's HIV risk tolerance and risk perceptions were explored using three strategies: 1) a previously validated survey question (21) about tolerance of risk in general (not specifically related to sexual behaviors or health), 2) a vignette to elicit perceptions of risk for vignette characters on a 0-10 scale (similar to previous studies on perceptions of risk) (22-24) and the elicitation of personal risk on a 0-10 scale, and 3) IDIs on personal perceptions of HIV risk both before and after discussions on HIV testing with male partners.

Survey questions on risk tolerance included the following three questions: “Is your partner generally a person who is fully prepared to take risks or does [he/she] try to avoid taking risks?”, “Are you generally a person who is fully prepared to take risks or do you try to avoid taking risks?”, and “Please rate yourself from 1 to 10, where 1 means you are unwilling to take any risks and 10 means you are always willing take risks.” Risk ‘ladders’ – images of a ladder with increasing numeric associations assigned to each rung – were used to aid participants in eliciting their perception of personal risk of contracting HIV, as well as to guide discussions of risk associated with the vignette characters (described in more detail below).

Female participants were also asked about their willingness to talk to their male partners about their study participation, getting tested for HIV, offer them a list of referral services for HIV testing, and have their current male partner(s) come in for an IDI. Those women who agreed to do so were followed-up approximately one month later to confirm that they had spoken with their partners and to reconfirm their willingness to have staff contact their male partner for an interview. Male partners were then contacted and scheduled to come in for an IDI. Interviews with men covered similar topics as those with women.

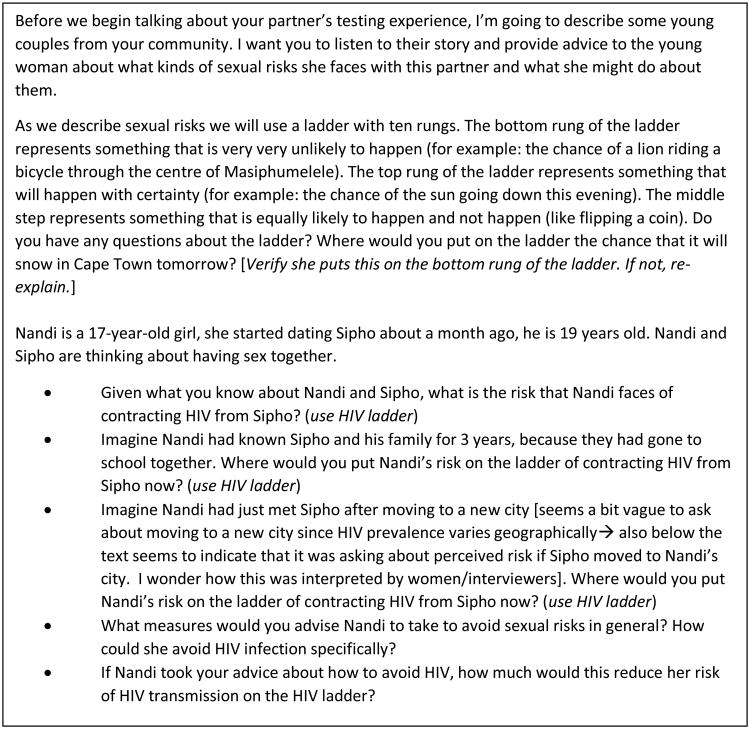

All female participants who agreed to speak to their male partners were invited to return for a second IDI to discuss their experiences talking to their male partners and the effect of this conversation on their HIV risk perception and interest in oral PrEP. It was during this follow-on IDI that women were asked to respond to a risk vignette. The risk vignette presented a case of a young woman in a relationship. Participants were asked to reflect on the level of HIV risk of the vignette's characters, ranked on a ladder with values of 0-10. The vignette featured a new relationship with a two-year age difference between partners. After introducing the vignette, elements of the narrative were varied including asking participants to consider how long the characters have known each other, prevention methods, and contextual elements such as moving to a new city. The vignette is included in Figure 1. Following the case, participants were asked to reflect on their own level of risk. All interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes to one hour.

Figure 1. HIV risk vignette.

Trained research staff of the same gender as the participants conducted all interviews at the research clinic site in private rooms to allow for confidentiality. Interviewers were selected based on prior qualitative research experience and local language skills. A one-day protocol training was conducted along with additional observed mock interviews prior to study start. The study protocol and all data collection tools were reviewed and approved by the ethics review committees of all participating organizations. All participants provided written informed consent prior to their participation.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data were tabulated using STATA (version 12.1). All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and translated into English. Every transcript was reviewed twice for quality control, first by researchers at the DTHF in South Africa then by the US-based data center (RTI/WGHI). All transcribed interviews were coded in Dedoose, a web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data (version 6.1.18, Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC www.dedoose.com) by the four-person analysis team. An initial codebook was iteratively developed based on the key research questions and refined upon review and subsequent coding of transcripts. An acceptable level of inter-coder reliability was set at ≥ 80% coding agreement. Throughout the analysis process, approximately 10% of the transcripts were used to create coding tests, which helped team members monitor and maintain a high-level of inter-coder reliability. Following each test, discrepancies were discussed, reconciled, and coded transcripts were updated to reflect agreements. The codebook was modified, as needed, based on these discussions. Code reports representing a combination of the codes risk, sexual relationships, HIV testing, trust, power, communication, and fidelity were reviewed and analyzed for additional themes which were then summarized into memos. Memos served as the basis for summarizing, interpreting and reporting qualitative results within the manuscript. The analysis of the male partner data followed the same process as those of the females, except content was ultimately extracted for each individual as a case study. A couple-based analysis was also conducted to explore congruencies and discrepancies in reports according to key topics – relationship and sexual power, sexual behaviors, communication and decision-making, HIV testing experiences and discussion with partners, and interest in PrEP – between male and female members of matched couples.

Results

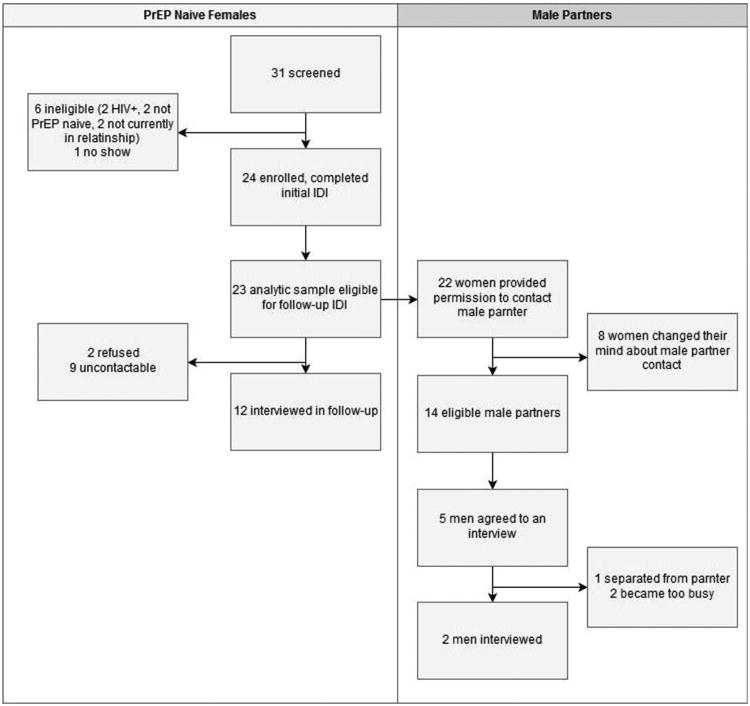

A total of 26 participants joined the study (Figure 2). These included 24 young women, 12 of whom participated in the second IDI. Twenty-two women initially agreed to speak to their male partners at the first interview, however upon telephonic follow-up only 14 women still agreed. Two male partners participated in an interview out of 14 eligible men whose female partners consented for their contact. Most male partners were not interested when contacted or never showed up for their IDIs despite multiple scheduling attempts. Among the 24 female participants, one was determined to be ineligible during the interview when she revealed that she knew her male partner was HIV- positive. This decreased the female analytic sample to 23.

Figure 2. Participant Screening and Enrollment.

Participant Characteristics

Table 1 presents female participant characteristics. Women's average age was 20 years old, the majority of whom lived with their parents or other family members. Social grants, grants administered by the South African Social Security Agency which are targeted at categories of people who are vulnerable to poverty and in need of state support, were their primary source of income, followed by family members and partners. Given the small number of men enrolled, male partner data is presented as a case study (see Table 2).

Table 1. Demographic and risk characteristics of PrEP naïve female participants.

| Demographic Characteristics | PrEP Naïve Women (N=23) |

|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |

| Mean age (range) | 20 (16.8-24.1) |

| Average age of partner | 20 |

| Avg. number of children (range) | 0.5 (0-2) |

| Who do you live with1 | |

| Parents | 13 |

| Other family members/non-parents | 15 |

| Primary sex partner | 1 |

| Other (alone and sibling) | 3 |

| Sources of incomea1 | |

| Formal employment | 4 |

| Self-employment | 1 |

| Family members | 8 |

| Partners | 6 |

| Social grant | 11 |

| Mean monthly income in Rand USD (range) | R765 $57 (14-3200240) |

| Mean weekly spending in Rand USD (range) | R105 $8 (20-30022) |

| Mean highest school grade reached (range) | 10 (7-12) |

| Reported Behaviors, Beliefs and Preferences | |

| Has a main sex partner | 96% |

| Average length of relationship in months (range; N) | 26(1-108; 22) |

| Partner provides financial/material support (N) | 82% (22) |

| Partner has other partners (N) | |

| Yes | 22% (22) |

| Don't know | 48% (22) |

| Average lifetime partners (range) | 4 (1-19) |

| Had penile-vaginal sex in the past 3 months | 82% |

| Condoms used during penile-vaginal sex | |

| Never | 5% |

| Sometimes/Occasionally | 63% |

| Always | 32% |

| Had penile-anal sex in the past 3 months | 4% |

| ≥2 sex partners in the past 3 months | 22% |

| Mean SPRS score (range)2 | 2.74 (2.3-3.4) |

| Risk tolerance on scale 1-10 (range) | 4.5 (1-9) |

| Self-reported likelihood of contracting HIV in the next year on scale 0-10 (range; N) | 1.6 (0-5; 12) |

Could mark all that apply

Low power 1-2.43; medium power 2.43-2.82; high power 2.82-4

Table 2. Male Partner Case Studies.

| Male, age 23, referring female partner age 21 |

Risk profile. Reports 2 lifetime sexual partners, reports that he always uses condoms in the past 3 months, he doesn't know if his partner is faithful, and ranked his overall risk taking as 5 out of 10. Relationship context. He considers the woman who referred him to the study to be his current main partner, but he's had sex outside the relationship twice. They've been dating for two months and they' don't see each other on a regular basis. He's happy with relationship, has no apparent trust issues, as evidenced by the fact that she doesn't question his drinking or other behaviors. They discuss sex just prior to it happening, mainly about level of interest and condoms and do not discuss HIV. He's never had a partner express interest in his HIV status or encourage him to test. His partner does insist on using condoms, but for contraceptive purposes. He reported letting her make decisions to avoid ‘spoiling the mood’ around sex. Comparison to female partner. Relationship was relatively new. At her first interview in Oct, there wasn't yet trust. They hadn't had sex yet so hadn't discussed sex, HIV, or contraception. She insists HIV testing and knowing your partner's status is important, but she hasn't brought it up with him. At her follow-up interview 3 months later, she says they broke up shortly after her first interview so she never brought up the study or HIV testing. She found him with another women when she came to talk to him about it. |

| Male, age 27, referring female partner age 23 |

Risk profile. Reports 30 lifetime sexual partners, reports always uses condoms in the past 3 months, and ranked his overall risk taking as 10 out of 10. Relationship context. According to him, the woman who told him about the study is a partner he regularly would have sex with, but would not categorize her as his main partner because he has other partners he has sex with. They met over a year ago and it seems that she does not know he has other partners. His partner insists on using condoms, but for contraceptive purposes. He finds that talking about sex is not an issue, they both have a chance to start these conversations and they respect the other person's opinion. He reports they also talk about HIV testing without issues and speak openly and make the decision to go get tested but never mentioned if they share their HIV statuses with each other. Comparison to female partner. She views him as her main partner. Reports using condoms ‘most of the time.’ They talk about sex, but he's hesitant. She won't sleep with a partner unless she knows his HIV status. Her knowledge of his last test is from a year ago. She was nervous to bring up testing after her initial IDI and says he responded angrily and didn't test. She's still not concerned since they use condoms. |

The average relationship length was 26 months. Over a fifth of participants believed that their partner had other partners and nearly half did not know if their partner had other partners. On average participants had four lifetime partners and most (82%) had sex in the past three months. Twenty two percent reported more than two partners in the last three months with less than a third reporting that they always use condoms. Despite these risks, among the subset participating in follow-on IDIs (N=12) where risk perceptions were elicited, risk perception was low with participants scoring their perceived risk as 1.7/10 on average. Participants' willingness to take risks averaged 4.5 with a range across nearly the entire distribution of risk tolerance. There were no significant differences between the women who completed a follow-up IDI compared to those who did not (analysis not shown).

Relationship Dynamics

Of relevance to HIV risk, three themes related to relationship formation, maintenance, and security were identified. These included: a) infidelity as the rule, not the exception b) a desire for and preservation of trust, and c) a lack of actualization of women's perceived power and effective communication within their own sexual relationships.

Infidelity

As highlighted above, female participants reported multiple sexual partners and uncertainty about their current male partner's fidelity. Discussions of how relationships were formed and broken, confirmed that the experience of infidelity was a common occurrence for these young women. In fact, infidelity often marked the end of a relationship, the news of which spread among social networks or directly from one's partner as “Jabu” (all names are pseudonyms) recounts.

“I met him on the train this guy, and I would go to him in [location referenced], and then one day when I was calling him he was not answering his phone and a girl answered his phone. He wrote me a message saying that he no longer wanted me – saying that he has another girl that he has found.” (Jabu, age 17)

Women reported that they also had multiple partnerships, and several women acknowledged cheating in their previous relationships. One woman described how her primary partner became suspicious after checking Facebook on her phone and the ensuing game of hide and seek to cover up.

“So during the night [while the current partner was sleeping] I got up and deleted the conversations on Facebook [with second partner]. Then in the morning he wanted the phone again, and I gave to him. So even though he was suspicious about something he never saw anything.” (Fezeka, age 23)

Desire for and Preservation of Trust

In the face of common occurrences of infidelity, acts to preserve trust or at least the appearance of trust became important: both behavioral patterns and psychological tools were utilized in this effort. This included keeping tabs on a partner's location, checking one another's phones, and choosing not to use condoms. One participant said she didn't use condoms with her partner because this would signify her distrust: “I do use protection [condoms] but not that much because to him it seems as if I don't trust him so he has an issue with using it because we were not used to using it at first so why come with it now?” (Lulama, age 18)

Women also reframed trust on different dimensions such as duration of the relationship or prospects for a committed relationship rather than on fidelity or HIV risk. “But [for] me not trusting him it's not about him having other people, but it's about him lasting with me.” (Lulama, age 18)

When trust was linked to fidelity and/or HIV risk, participants said they could trust their partners until proven otherwise. For example “Jabu” didn't feel she should worry until she would have clear evidence that her partner was cheating, or “as long as I don't see any funny things [giggles].” (Jabu, age 17)

Communication and Power in Relationships

Women expressed relatively high levels of relationship power, both via the SRPS and in the descriptions of their relationships. On average, women scored 2.74 on the SRPS (range = 2.3-3.4), a score that is interpreted as ‘medium’ levels of power in a relationship.

Discussions relevant to relationship power were focused primarily on communication and decision-making around sex and condom use, with family planning and PrEP coming up infrequently. Good communication was viewed as important and trust building. About a third of participants described having comfortable conversations with their male partners around sex, although several of these women admitted these conversations don't happen often. Sex, contraception, STIs, and HIV were all topics of discussion. While most women had spoken to their partners about HIV testing at some point, several women specified that HIV, as opposed to other topics, is not discussed often. One woman explained why they don't talk about HIV by saying, “I think we trust each other on that. Obviously if he had HIV, I'd gotten it too by now.” (Lulama, age 18)

Across all areas of decision-making, women stated that while in general men have more power in society, they personally held some power in their own relationships and with sexual health related decisions. Condom use, in particular, was reported as a domain where more women exerted control over the decision on whether or not to use. One woman described using condoms as a source of power over sex: “if he wants us to have sex we are going to use a condom, if ever he doesn't want we won't have sex.” However, she later described the decision as a more subtle reminder: “Most of the times I would be the one reminding him.” (Zintle, age 20)

Despite their asserted power, participants recognized that male partners often have the last say when it comes to most decisions. A couple of women explicitly said that it is culturally prescribed for men to have more power, to be the “head of household” and to have the final say regarding sex:

…“it is the men who have the power. […] He is the head of the house. He is the one I listen to, and so even to conclude, he has to do the concluding.” (Jabu, age 17)

There was no apparent connection between women's ranking on SRPS (low, medium, or high) and their described decision-making power. For example the two women who discussed men's culturally prescribed power were respectively scored as medium and high power.

Assessment of Risk

Explorations of risk at follow up visits concurred that duration of relationship and emotional factors linked to trust in the relationship influenced perception of young women's personal HIV risk.

Relationship Length Influences Risk

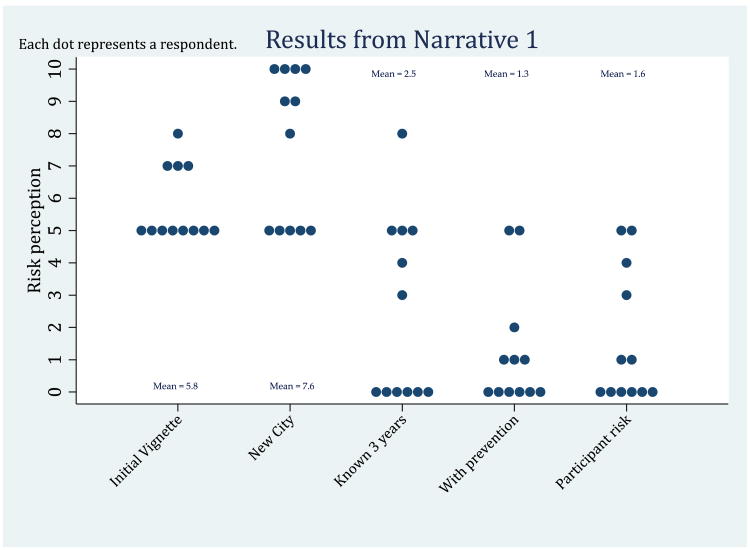

While the risk vignette examined different permutations of factors that may influence risk, one factor that emerged as important to participants' estimation of risk was how long the characters were said to know each other. In the vignette, participants were asked to estimate risk of two characters who began dating one month ago. Participants were then asked to re-consider the perception of risk considering that their male partner had just moved to a new city, then considering that they had known each other for at least three years, and finally considering that the female partner takes measures to avoid sexual risks recommended by the study participant.

As seen in Figure 3, estimation of risk increased if the male partner had just moved to the city and decreased when the characters had known each other for much longer and when they were using recommended prevention methods. The last column represents participants own risk perception scores. Participants own risk perceptions closely mirror the estimate risk for vignette characters who have known each other for three years or are using recommended prevention strategies. This is despite the fact that among this population, the average relationship duration was shorter (26 months) and only 26% of participants report using condoms all the time with their partners.

Figure 3. Risk Estimation for components of Vignette 1.

Participants also stated that partners with whom they have had longer relationships bring less risk. “Her chances [of contracting HIV] are small…. Because they have known each other for a long time. You see this story is similar to my previous relationship. They have known each other for a long time, being both open to one another and doing things together.” (Lulama, age 18)

Furthermore, among women who were in their current relationship for <1 year, there was a trend for perceived HIV risk to be ranked higher (average score of 3.5 out of 10) compared to those in a relationship for 1+ year (average score of 1.3 out of 10; t-statistic = -1.86, p=value = 0.096). Notably, length of relationship was not associated with suspicion that a male partner may have other sex partners.

Emotional Context Influences Risk

Personal and male partner's commitment were also key to estimating risk in a relationship. When discussing what information might need to be known to better understand risk for the characters in the vignette, several women cited the level of commitment of the male partner: “I'd like to know how serious is Thando about Funeka in terms of having a future together. Does he see himself with Funeka forever or not?” (Zintle, age 20)

Similarly, a sense of trust was also extended to interpretations of one's risk when assessing the influence of knowing a male partner's HIV status. All 23 female participants committed to discuss HIV testing and serostatus with their male partner during the first IDI, but 8 had changed their mind when contacted later for confirmation of male partner contact details. Almost half (11) of women specifically said they would share details of their own study participation and HIV negative results received during screening as a way to encourage such discussion with their male partner in a context where introducing the topic of HIV may otherwise raise issues of mistrust.

In the initial IDI, women all agreed that HIV testing with one's partner was important with several women linking this testing to an ability to increase the seriousness or quality of the relationship. HIV testing was linked to trust in the relationship in that agreeing to test could avoid mistrust, sharing one's results could build trust, and HIV-negative results could be a sign of fidelity – all of which would decrease one's sense of HIV risk. A few women, however, acknowledged that trust could be compartmentalized to either take into account HIV-testing or ignore it. For example, one woman explained how she trusts her partner in other areas, except for his HIV status, “I actually trust my partner sometimes in other things, but now in this…in the HIV status thing, I don't trust him because it's like he's hiding some important thing…It makes me feel at risk because I don't know his status.” (Sisipho, age 19). This connection between a commitment to disclose everything and trust was expanded upon by another participant who intended to discuss HIV testing with her partner:

“There is nothing that is going to make it [i.e. discussing HIV status with her partner] hard. What could make it hard would be hiding it from him first, and then now you do not know how to handle it because you were not honest with him from that beginning. You just need to say it at the beginning.”] (Nomble, age 17)

Of the fourteen women who came for a follow-up IDI, all, but one reported speaking to their partners about HIV testing, including the woman quoted above. These conversations were often preceded by a sense of nervousness, linked to various reasons, including the current relationship quality. Only one of the fourteen women reported that her partner actually tested for HIV following their discussion. Nevertheless, women's risk perception level did not substantially shift by the time of the follow-up IDI. The one woman whose partner tested reported an increase in relationship trust, while the others rationalized no change in their risk by stating they themselves have a history of staying negative within the context of this relationship or they hadn't seen any suspicious or ‘unusual’ behaviors from their partner, which supported their trust and overruled this recent lack of action.

Interest in HIV Prevention and Oral PrEP

Regardless of their relationship context or their stated perception of risk, most women expressed a general interest in preventing HIV as well as in oral PrEP. Motivating this interest was a desire to stay HIV negative in order to protect their future: “I'm more motivated to protect myself from getting infected because I'm still young and have a bright future ahead of me that I would like to focus on.” (Akhona, age 19)

The majority of these women were aware of and used condoms, albeit inconsistently, but oral PrEP was a new and intriguing possibility for prevention. In fact, personal autonomy as well as inconsistent condom use were cited as a reasons for interest in oral PrEP: “Because I do not necessarily have to use a condom, I can take it [oral PrEP] myself.” (Nceba, age 18)

Another participant invoked her motivation to use PrEP as “… the challenges of this world, and also that I do not like using a condom, and that I am having unprotected sex all the time, and that what is motivating me.” (Buhle, age 22) Other potential motivators for oral PrEP included fear of rape, given its high incidence in the community, while potential challenges included cost and remembering to take the pill daily. All factors mentioned involved the individual or community level, as opposed to relationship contexts.

Discussion

In our mixed method study of young women's relationship context and risk perception in a Cape Town township, we found that young women's decision-making around HIV risk is driven by emotion. For one, while young women connect risk with knowledge of risky and protective behaviors (e.g. regular HIV testing, condom use, fidelity), it is also connected with feelings of trust. This finding is consistent with evidence that individuals may tend to form judgments (including judgments of the risk posed by a partner) by using an “affect heuristic” or by consulting their feelings as their primary guide (25). Secondly, when feelings of risk conflict with a desire to maintain trust in a relationship, trust was often redefined to overcome concerns around risk. This finding is also consistent with evidence that individuals tend to engage in “motivated reasoning” by subtly changing the way they process new information to favor their underlying desires (18, 26). Motivated reasoning would have the potential to influence, for example, the processing of information provided about new risk prevention strategies such as PrEP if it came into conflict with a desire to maintain trust in a valued partner.

Early relationships are not surprisingly fraught with challenges around communication, decision-making, and more generally inequitable power dynamics. In this study, young women's narratives of themselves and their relationships often were optimistic and backed by relatively high scores on the Sexual Relationship and Power Scale (SRPS). Yet when tested by our request to discuss HIV with their partners, principles of open communication and shared decision-making faltered. This is not out of line with several studies in South Africa, which indicate a shift away from traditional gender norms (27-31), yet a remaining gap between these new ideals and the reality of women's lived experiences (32). This may present a challenge with the use of previously developed relationship power scales with urban South African youth. While the SRPS in particular has been validated with young women in South Africa, the population was more rural than in our study (33). In its validation, it was also noted that the decision-making subscale was less internally consistent than the control sub-scale (34), which may explain the difference in the qualitative discussions of power versus decision-making.

The limited engagement of men, both as reported by the women in follow-up interviews and demonstrated by male partners' lack of participation in the study, suggest that more needs to be done to support male and female partners in their quest for safe and fulfilling relationships. Young women expressed a desire for committed, trusting, and long-lasting relationships, but the context of frequent infidelity represents a barrier for many. The implementation of more programs focusing on healthy relationships, and the promotion of PrEP in this context, may serve to both ensure that PrEP does not suffer the fate of condoms (i.e. being linked to mistrust)(35-38). This may have the dual benefit of improving young women and men's ability to reach their goals of respectful, consenting, and supportive relationships.

Despite these insights, this study has several limitations. For one, the qualitative exploratory nature of the study limits our ability to make inferences for a larger body of youth in Cape Town or beyond. Low follow-up rates among women and minimal participation of men, in particular, also limit our perspectives of partner communication and challenge our understanding of male perspectives on these issues. The civil unrest in the community, which led to community shut-downs (20), delayed our study implementation timeline and caused our follow-up period to fall during school exam periods and the December school holidays, a time when people tend to return to their natal homes in the Eastern Cape. These disruptions may have contributed to our low follow-up rates among women. In addition, for male partners, it's important to note that given one objective of this research was to learn how well engaging male partners via women would work, we did not go out of our way to incentivize men to participate like other studies might.

The challenge we faced in engaging men and their resulting lack of participation is nonetheless a useful finding in itself and one that has been validated by numerous sexual and reproductive health studies (39, 40). Reasons cited for this challenge include norms around masculinity that inhibit men's use of healthcare, but which also promote inequity within relationships. Anecdotally we heard there was some concern regarding the requirement or confidentiality of HIV testing at the study site which may have discouraged them to come in. This was despite the fact that we did not plan to test male partners for HIV and were explicit about this when recruiting them to the study. These again point towards several needs, including a need for programming that is not entirely health focused and which addresses gender norms in sexual relationships, HIV prevention methods that women can use with limited partner engagement, and innovative ways to engage men in HIV testing. Directly addressing harmful gender norms and promoting gender-equitable relationships has consistently been shown to improve the effectiveness of health programs (41, 42), and evidence from the microbicide field indicates that involving men can improve relationship communication (43, 44). However, in the interim, PrEP remains a critical tool for women's HIV prevention given its potential to be used discretely in the case of uncooperative partners. While our findings did not demonstrate that male partner testing – or lack thereof – influenced women's risk perception, engaging men in HIV testing and care remains vital to reaching global HIV prevention targets. As such, innovative strategies for male partner testing that don't require men to come to clinics, such as the provision of self-tests through female partners should continue to be tested. Yet, putting the onus of engaging young men into HIV prevention on their female sex partners may not only be challenging for young women to navigate, but may also continue to place an inequitable burden for HIV prevention on women.

Now that oral PrEP is being rolled out in South Africa, understanding young women's relationships, feelings of HIV risk, and motivation to prevent HIV with this new tool is all the more pressing. While research in the context of PrEP clinical trials indicate that a sense of HIV risk was associated with greater PrEP adherence (45), our own findings suggest that caution should be taken before emphasizing risk as a strategy for creating demand around HIV prevention, including PrEP among young women. Perhaps a focus on positive healthy relationships may create a more welcoming context for promoting PrEP use. By strongly emphasizing risk as a rationale for PrEP use, we may inadvertently connect the concept of mistrust with PrEP use, forcing individuals to choose between the logic of PrEP and their strong feelings of trust.

Acknowledgments

We would like to pay tribute to the women and men who participated in this study, their participation made this study possible. The contributions of Jonah Leslie are acknowledged as critical in the analysis of this study. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01MH107251). Writing of this manuscript was supported in part by internal funds from RTI International. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the authors' employers or funders.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grant number 1R01MH107251).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards: Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Medicines Control Council approves fixed -dose combination of tenofovir disoproxyl fumarate and emtricitabine for pre-exposure prophylaxis of HIV [press release] Pretoria: Registrar of Medicines, Medicines Control Council; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Recommendations on the Use of PrEP for All Populations, PEPFAR Scientific Advisory Board (SAB) PrEP Expert Working Group (EWG); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. WHO Expands Recommendation on Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis of HIV Infection (PrEP) Geneva: WHO; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baeten JM, Palanee-Phillips T, Brown ER, Schwartz K, Soto-Torres LE, Govender V, et al. Use of a vaginal ring containing dapivirine for HIV-1 prevention in women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375(22):2121–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, Gomez K, Mgodi N, Nair G, et al. Tenofovir-Based Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Infection among African Women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(6):509–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, Agot K, Lombaard J, Kapiga S, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(5):411–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNAIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.UNAIDS. The Gap Report. Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, Zuma K, Jooste S, Zungu N, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behavior Survey, 2012. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Germain A. Integrating gender into HIV/AIDS programmes in the health sector: tool to improve responsiveness to women's needs. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2009;87(11):883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health education & behavior. 2000;27(5):539–65. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amico KR, Mansoor LE, Corneli A, Torjesen K, van der Straten A. Adherence support approaches in biomedical HIV prevention trials: experiences, insights and future directions from four multisite prevention trials. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(6):2143–55. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0429-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Straten A, Stadler J, Montgomery E, Hartmann M, Magazi B, Mathebula F, et al. Women's experiences with oral and vaginal pre-exposure prophylaxis: the VOICE-C qualitative study in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Haberer JE, Baeten JM, Kintu A, Psaros C, et al. What's love got to do with it? Explaining adherence to oral antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV serodiscordant couples. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2012;59(5) doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824a060b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celum CL, Delany-Moretlwe S, McConnell M, Van Rooyen H, Bekker LG, Kurth A, et al. Rethinking HIV prevention to prepare for oral PrEP implementation for young African women. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(4) doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.4.20227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, Castellanos FX, Liu H, Zijdenbos A, et al. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nature neuroscience. 1999;2(10):861–3. doi: 10.1038/13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson SB, Blum RW, Giedd JN. Adolescent maturity and the brain: the promise and pitfalls of neuroscience research in adolescent health policy. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45(3):216–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Epley N, Gilovich T. The mechanics of motivated reasoning. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2016;30:133–40. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Middelkoop K, Bekker LG, Myer L, Whitelaw A, Grant A, Kaplan G, et al. Antiretroviral program associated with reduction in untreated prevalent tuberculosis in a South African township. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2010;182(8):1080–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0598OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolley C. No end in sight for Masi protests. IOL News. 2015 Oct 25; Sect. Crime & Courts. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dohmen T, Falk A, Huffman D, Sunde U, Schupp J, Wagner GG. Individual risk attitudes: Measurement, determinants, and behavioral consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association. 2011;9(3):522–50. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corneli A, Field S, Namey E, Agot K, Ahmed K, Odhiambo J, et al. Preparing for the rollout of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): a vignette survey to identify intended sexual behaviors among women in Kenya and South Africa if using PrEP. PloS one. 2015;10(6):e0129177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gourlay A, Mshana G, Birdthistle I, Bulugu G, Zaba B, Urassa M. Using vignettes in qualitative research to explore barriers and facilitating factors to the uptake of prevention of mother-to-child transmission services in rural Tanzania: a critical analysis. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2014;14(1):21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai AC, Kakuhikire B, Perkins JM, Vorechovska D, McDonough AQ, Ogburn EL, et al. Measuring personal beliefs and perceived norms about intimate partner violence: Population-based survey experiment in rural Uganda. PLoS medicine. 2017;14(5):e1002303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slovic P, Finucane M, Peters E, MacGregor DG. In: Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment. Gilovich T, Griffin D, Kahneman D, editors. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pronin E, Gilovich T, Ross L. Objectivity in the Eye of the Beholder: Divergent Perceptions of Bias in Self versus Others. Psychological Review. 2004;111(3):781–99. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.3.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hunter M. Masculinities and multiple-sexual partners in KwaZulu Natal: The making and unmaking of Isoka. Transformations. 2005;54:123–53. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrell R. The times of change: Men and masculinity in South Africa. In: Morrell R, editor. Changing men in Southern Africa. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press; 2001. pp. 3–56. [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Sullivan LF, Harrison A, Morrell R, Monroe-Wise A, Kubeka M. Gender dynamics in the primary sexual relationships of young rural South African women and men. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2006;8(2):99–113. doi: 10.1080/13691050600665048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shefer T, Crawford M, Strebel A, Simbayi L, Dwadwa-Henda N, Cloete A, et al. Gender, power and resistance to change among two communities in the Western Cape, South Africa. Feminism & Psychology. 2008;18(2):157–82. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strebel A, Crawford M, Shefer T, Cloete A, Henda N, Kaufman MR, et al. Social constructions of gender roles, gender-based violence and HIV/AIDS in two communities of the Western Cape, South Africa. Sahara Journal. 2006;3(3):516–28. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2006.9724879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Anderson A, Maman S. ‘If I buy the Kellogg's then he should [buy] the milk’: young women's perspectives on relationship dynamics, gender power and HIV risk in Johannesburg, South Africa. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2012;14(5):477–90. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.667575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet. 2010;376:41–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60548-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pulerwitz J, Gortmaker S, DeJong W. Measuring relationship power in HIV/STD Research. Sex roles. 2000;432(7/8):637–660. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fox AM, Jackson SS, Hansen NB, Gasa N, Crewe M, Sikkema KJ. In their own voices a qualitative study of women's risk for intimate partner violence and HIV in South Africa. Violence Against Women. 2007;13(6):583–602. doi: 10.1177/1077801207299209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harrison A, Xaba N, Kunene P. Understanding safe sex: gender narratives of HIV and pregnancy prevention by rural South African school-going youth. Reproductive health matters. 2001;9(17):63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(01)90009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bryan A, Kagee A, Broaddus MR. Condom use among South African adolescents: Developing and testing theoretical models of intentions and behavior. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(4):387. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sayles JN, Pettifor A, Wong MD, MacPhail C, Lee SJ, Hendriksen E, et al. Factors associated with self-efficacy for condom use and sexual negotiation among South African youth. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2006;43(2):226. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000230527.17459.5c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hensen BTS, Lewis JJ, et al. Systematic review of strategies to increase men's HIV-testing in sub-Saharan Africa. Aids. 2014;28(14):2133–45. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Musheke MNH, Gari S, et al. A systematic review of qualitative findings on factors enabling and deterring uptake of HIV testing in Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):220. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barker G, Ricardo C, Nascimento M. Engaging Men and Boys in Changing Gender-Based Inequity in Health: Evidence From Programme Interventions. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ricardo C, Eads M, Barker G. Engaging Boys and Young Men in the Prevention of Sexual Violence: a Systematic and Global Review of Evaluated Interventions. Cape Town/Rio de Janeiro: Sexual Violence Research Initiative/Instituto Promundo. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Montgomery ET, vdS A, Chidanyika A, Chipato T, Jaffar S, Padian N. The importance of male partner involvement for women's acceptability and adherence to female-initiated HIV prevention methods in Zimbabwe. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(5):959–69. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9806-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mngadi KT, M S, Grobler AC, Mansoor LE, Frohlich JA, Madlala B, et al. Disclosure of microbicide gel use to sexual partners: influence on adherence in the CAPRISA 004 trial. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(5):849–54. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0696-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Corneli A, Wang M, Agot K, Ahmed K, Lombaard J, Van Damme L, et al. Perception of HIV risk and adherence to a daily, investigational pill for HIV prevention in FEM-PrEP. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2014;67(5):555–63. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]