Abstract

Objective

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a chronic condition affecting over 100 000 individuals in the United States, predominantly from vulnerable populations. Clinical practice guidelines, written for providers, have low adherence. This study explored knowledge about guidelines; desire for guidelines; and how technology could support guideline awareness and adherence, examining current technology uses, and user preferences to inform design of a patient-centered guidelines application in a chronic disease.

Methods

This cross-sectional mixed-methods study involved semi-structured interviews, surveys, and focus groups of adolescents and adults with SCD. We evaluated interest, preferences, and anticipated benefits or barriers of a patient-centered adaptation of SCD practice guidelines; prospective technology uses for health; and barriers to technology utilization.

Results

Forty-seven individuals completed surveys and interviews, and 39 participated in three separate focus groups. Most participants (91%) were unaware of SCD guidelines, but almost all (96%) expressed interest in a guidelines application, identifying benefits (knowledge, activation, individualization, and rewards), and barriers (poor information, low motivation, and resource limitations). Current technology health uses included information access, care coordination, and reminders about health-related actions. Prospective technology uses included informational messaging and timely alerts. Barriers to technology use included lack of interest, lack of utility, and preference for direct communication.

Conclusions

This study’s findings can inform the design of clinical practice guideline applications, suggesting a promising role for technology to engage patients, facilitate care decisions and actions, and improve outcomes.

Keywords: sickle cell disease, guidelines, mobile health, technology

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a hereditary hemoglobin disorder that affects over 100 000 Americans, primarily from vulnerable populations of lower socioeconomic status and from racial or ethnic minorities.1,2 The acute and chronic complications of SCD substantially impact both affected individuals’ health and utilization of healthcare services. Adults with SCD account for 197 000 emergency room visits per year and, on average, each accrue $900 000 in lifetime costs of care by age 45.3–5

As with most chronic conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, and asthma, clinicians’ care of SCD (including health maintenance, treatment, and prevention of complications) is informed by clinical practice guidelines.6 However, poor guideline utilization or adherence is a common barrier to the long-term health of individuals with chronic conditions,7–9 including SCD.10–15 Examples of poor SCD guideline adherence include the utilization of hydroxyurea therapy in only 20%–30% of eligible individuals, and the 45% completion rate of annual stroke screening among eligible children.15–17

Traditionally, guidelines are written for clinicians, guiding their disease management instructions to patients. However, patients, through their behaviors, are most directly responsible for acting in accordance with the guidelines. While technologies are increasingly used to support knowledge and self-management in individuals with chronic conditions like SCD, no studies have considered technology as a means to deliver patient-centered guidelines for chronic disease management.18–26 A “guidelines technology” is a potential opportunity in consumer health informatics to leverage commonly used modalities to educate, engage, and activate patients, improving their involvement in evidence-based decision-making and care. Optimizing care using technology could be particularly beneficial, but possibly challenging, in a predominantly vulnerable population with multiple comorbidities, such as SCD. To address these consumer health informatics gaps, this study sought to assess the SCD community’s interest in clinical practice guidelines, and how individuals with SCD could use technology to be informed about guidelines, engage in shared decision-making surrounding their care, and thereby support adherence to guideline recommendations.

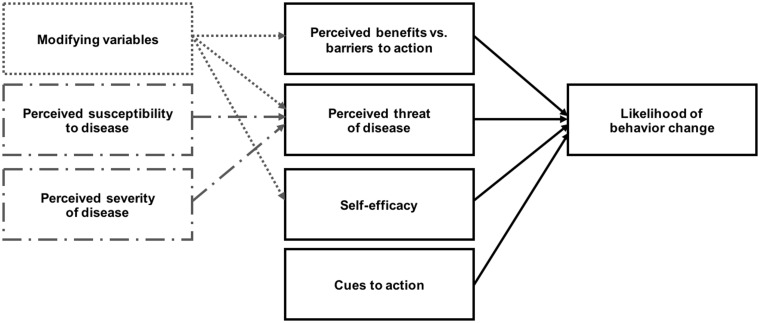

To understand benefits and barriers to technologies for improving patient adherence to clinical practice guideline recommendations, we used the Health Belief Model (HBM) as our theory for health behavior decision-making (Figure 1).27–29 According to the HBM, engagement in a health behavior depends upon an individual’s perceptions of 4 parameters: (1) susceptibility, the risk of experiencing disease or its effect(s); (2) severity, the seriousness of the condition or its consequences; (3) benefits, the anticipated positive outcomes of a behavior on disease risk or burden; and (4) barriers, the costs or adverse effects of a health behavior, and the possible difficulties or deterrents preventing its completion. These parameters are also influenced by patient-specific demographic, psychological, and socioeconomic determinants of behavior, as well as other modifying factors such as cues to action and self-efficacy.

Figure 1.

The Health Belief Model.

Considering the challenges with under-utilization of, or nonadherence to, clinical practice guidelines, and the high rates of technology penetration among demographic groups over-represented in the SCD population (e.g., younger age, low socioeconomic status, and racial or ethnic minority background), we believe a patient-centered application adapting recommendations of the 2014 Evidence-Based Management of Sickle Cell Disease Expert Panel Report could support awareness of and adherence to guidelines for individuals with SCD, as well as engage these individuals to have conversations with their providers.6,30 To inform application design, we conducted a cross-sectional mixed-methods study using semi-structured interviews, surveys, and focus groups, evaluating if individuals with SCD know about guidelines; whether they would want these guidelines; and the perceived benefits and barriers to, as well as preferences for, a proposed application for access and adherence to SCD guidelines. In addition, we assessed individuals’ use of technology to obtain health information and support disease management practices. These inquiries were guided by the HBM, which we applied to assess the factors influencing individuals’ willingness to use health information technologies to support consequent engagement in health-related actions.

OBJECTIVES

The research questions in this study were as follows:

(1) Do individuals with SCD know what guidelines are, would they want to have guidelines, and do they perceive an application adapting clinical practice guidelines for their access and use in self-care as desirable and/or useful?

(2) What are preferences for features and functions, or possible pitfalls to avoid, in a guideline-based application?

(3) What are the perceived benefits of this application and potential barriers to its adoption?

(4) How do individuals with SCD currently use technology for health-related purposes, how would they like to use technology for their health, and what barriers limit technology use for health?

Methods

Study Instruments

This mixed-methods study involved 2 phases: (1) semi-structured interviews and surveys and (2) focus groups. These instruments were created by members of the research team and SCD clinicians, then tested by a few individuals with SCD prior to conducting the study.

The semi-structured interview was comprised of fixed-choice and open-ended questions regarding individuals’ preferences for an adaptation of clinical practice guidelines for individuals with SCD use. Specific questions included: (1) prior awareness of the guidelines; (2) interest in guideline access and use; (3) preferred formats for receiving guidelines, such as electronic vs paper form, self-guided viewing vs explanation by a clinician, and favored technological means of access; (4) anticipated benefits in SCD care from guideline use; (5) perceptions of how technology could facilitate guideline adherence; and (6) anticipated barriers to guideline use.

The survey consisted of free-text and multiple-choice items about participant demographics and consumer technology use, including patient portals, text messaging, mobile applications, social media, websites, and online discussion groups or forums. Surveys asked about purposes of current or previous technology use in health and non-health contexts, interest in use for health, and anticipated purposes or goals of such use.

The focus group centered on preferences for technology to acquire health information; current and prospective uses of technology for disease management; and barriers to use of technology for disease management.

We applied the HBM to guide questions regarding preferences for application design to promote guideline adherence. The interview and focus group elicited perceived benefits and barriers to guideline application use. The interview and survey explored how respondents use technology to access information for SCD management, which frames their understanding of disease severity and susceptibility and therefore modifies health behaviors. Cues to action and self-efficacy were evaluated through interview questions on whether, and how, technology could facilitate guideline adherence and improve self-care.

Population, Setting, and Procedure

For the survey and interview phase, we enrolled a separate cohort of adolescents and adults aged 12–70 years who had a diagnosis of SCD and were prescribed daily medications such as hydroxyurea. Participants were selected among individuals seen in adult and pediatric outpatient clinics affiliated with the Vanderbilt-Meharry Center for Excellence in SCD (Nashville, TN) from September 2016 to July 2017, using a convenience sampling method. Individuals with SCD were consented for participation during routine clinic appointments, then scheduled to complete the in-person survey and interview at a later date. Participants unable to complete surveys or interviews (e.g., due to severe cognitive dysfunction limiting responses to questions) were excluded. We administered the survey to each participant using a Research Electronic Data Capture survey on a laptop computer.31 Study subjects were asked to complete missing items or clarify free-text items where appropriate. Afterwards, each participant completed a semi-structured interview, conducted according to an interview guide. Interviews were recorded, then transcribed and de-identified for analysis.

We also conducted 3 focus groups involving adults with a diagnosis of SCD or SCD trait. Participants were recruited through the Sickle Cell Foundation of Tennessee, a community-based organization. Recruitment strategies included flyers and emails to identify potential participants. Focus groups were conducted by a facilitator using a written moderator’s guide. The groups were audio recorded, then transcribed and de-identified for analysis.

The research protocol and all study materials were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board before participant enrollment and data collection were initiated.

Analysis

An inductive-deductive, qualitative content analysis approach was used to identify emerging themes.32 Two members of the research team (AU, RMC) reviewed 10 interview transcripts to identify themes and develop a list of terms (i.e., a codebook). We initially used an open-coding methodology, recording all codes that emerged from the data.33,34 Once we had an initial set of concepts, we condensed them into summative themes, then modified the codebook to associate themes to the component(s) of the HBM with which they most closely corresponded (e.g., recognizing the “knowledge” theme as reinforcing perceptions of severity or susceptibility). As additional transcripts were coded and new themes emerged, the codebook was iteratively refined and earlier transcripts recoded according to codebook revisions. All themes corresponded to an HBM component. The codebook was applied for thematic analysis using Dedoose (Dedoose: Version 7.0.23, SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC; Los Angeles, LA; www.dedoose.com) to code free-text survey and interview responses, and Microsoft Excel for focus groups. Two authors (AU, RMC) independently applied codes, then resolved discrepancies through discussion. Coding occurred concurrently with data collection until thematic saturation was reached.

For fixed-choice items, we calculated descriptive statistics using Stata (Stata Statistical Software: Release 14; StataCorp, 2015; College Station, TX, USA) and SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows: Version 24.0; IBM Corp, 2016; Armonk, NY, USA) which were reported as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and medians and ranges for continuous variables.

Results

Participants Were Primarily Adults Representing a Broad Range of Socioeconomic Characteristics

For the surveys and interviews, we approached 81 adolescents and adults with SCD meeting the study inclusion-exclusion criteria. Of those approached, 75 of 81 participants (93%) were enrolled in the study, from which 47 of 75 individuals (63%) completed the interview and survey, including one partial response. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. The study population had a median age of 28.0 years (range: 14–61), was predominantly Black (92%) and a majority had Hemoglobin SS genotype (57%). They had a relatively even distribution of genders (47% male, 53% female) and education levels, and were primarily lower-income (64% with individual annual income <$45 000).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Respondents

| Variable | Focus group (N = 39) | Survey/interview (N = 47) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median, range) | 44.8 (25–66) | 28.0 (14–61) | |

| Gender (n, %) | |||

| Male | 9 (23) | 22 (47) | |

| Female | 30 (77) | 25 (53) | |

| Race (n, %) | |||

| Black | 39 (100) | 43 (92) | |

| Other | – | 4 (9) | |

| SCD genotype (n, %) | |||

| Hb SS | 13 (33) | 27 (57) | |

| Hb SC | 8 (21) | 7 (15) | |

| Hb Sβ0 | 1 (3) | 9 (19) | |

| Hb Sβ+ | 4 (10) | 3 (6) | |

| Hb AS | 7 (18) | – | |

| Other/unknown | 4 (10) | 1 (2) | |

| Do not know/declined | 2 (5) | – | |

| Education (n, %) | |||

| 8th grade or less | 3 (8) | 2 (4) | |

| High school | 4 (10) | 11 (23) | |

| Some college | 17 (44) | 11 (23) | |

| 2-year college degree | – | 8 (17) | |

| 4-year college degree | 9 (23) | 12 (26) | |

| Graduate degree | 4 (10) | 3 (6) | |

| Do not know/declined | 2 (5) | – | |

| Income (n, %) | Household | Individual | Household |

| $10 000 or less | 8 (22) | – | – |

| $10 001–25,000 | 12 (32) | – | – |

| $25 001–35,000 | 5 (14) | – | – |

| $35 001–45 000 | 4 (11) | – | – |

| $45 000 or above | 8 (22) | – | – |

| Under $15 000 | – | 20 (43) | 9 (19) |

| $15 000–44 999 | – | 10 (21) | 8 (17) |

| $45 000–79 999 | – | 4 (9) | 9 (19) |

| $80 000 or above | – | 1 (2) | 5 (11) |

| Do not know/declined | 2 (5) | 12 (26) | 16 (34) |

Continuous variables are displayed as mean (standard deviation [SD]), and categorical variables are displayed as (n, %).

Focus group participants included 39 adults (ages 18 and over) with SCD or SCD trait. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1, including 2 partial responses. The focus group population had a median age of 44.8 years (range: 25–66) years, was predominantly female (79%) and had Hemoglobin SS, SC, or AS genotype (27%, 24%, and 21%, respectively). They represented a broad range of educational and income levels.

Respondents Generally do not Know About Guidelines, but after Learning about Them, They Want to Access Them in Multiple Ways

Forty-seven respondents—including one partial response—completed the interview regarding interest in and preferences for a patient-facing adaptation of the clinical practice guidelines outlined in the 2014 Evidence-Based Management of Sickle Cell Disease Expert Panel Report.6 Only 4 respondents (9%) reported prior awareness of the guidelines or their contents. However, 44 (96%) expressed interest in learning about the content of the guidelines, either through explanation from a healthcare provider (n = 39, 85%), a paper copy of the guidelines (n = 33, 72%), or an electronic version of the guidelines (n = 38, 83%). Among the 38 participants requesting an electronic version of the guidelines, the most preferred modalities were email (n = 33, 87%), a mobile application (n = 25, 66%), a patient portal (n = 22, 58%), a website (n = 16, 42%), and social media (n = 9, 24%).

Respondents Have Insights into Potential Benefits, Barriers, and Attributes of Technology for Guidelines Awareness and Adherence

The qualitative analysis of focus group and interview transcripts identified respondents’ perspectives on the potential benefits of a guideline application to support SCD care, barriers to application use or guideline adoption, and preferred attributes to promote anticipated benefits or mitigate possible barriers in a guideline application (Table 2). The primary themes are summarized below.

Table 2.

User-proposed Benefits, Barriers, and Features or Functions of a Patient-centered Application for Guideline Access and Use

| Category/constituent code | Definition | Example [respondent or focus group #] |

|---|---|---|

| Benefit 1: Increased knowledge of disease and management strategies | ||

| Understandable and actionable format | Content is presented in a language and format that is accessible and actionable for a lay audience (e.g., bullet points or checklists, vs dense paragraphs) |

|

| Information | Information about SCD, its care, or updates in SCD research or practice collated in a “centralized,” credible resource |

|

| Sharing information to educate others | Guidelines or educational content can be shared to educate others involved in a user’s care, like clinicians or caregivers |

|

| Benefit 2: Activation and instruction for self-care | ||

| Instructional or motivational cues | Instructions, motivational cues, benchmarks, or other alerts/notifications for specific time-points or contexts in order to influence guideline adherence actions |

|

| Integration with other applications or devices | Integration of guidelines application with other technologies (e.g., mobile apps, patient portal, electronic health record) to track and reinforce behaviors |

|

| Interaction with caregiver | Interaction with a caregiver, support figure, or other individual (role not specified by respondent) within application |

|

| Interaction with clinician | Interaction with clinician within application, either direct (e.g., 2-way messaging) or indirect (e.g., clinician monitoring user health status) | “It should be interactive between people who are helping with the patient’s health: doctors, parents, friends. They should have access to see what you need to be doing, so that if you’re not doing it, they can give you that little push to do it.” [R33] |

| Interaction with other individuals with SCD | Interaction with individuals with SCD within application, either direct (e.g., 2-way messaging) or indirect (e.g., “news feed” with other users’ posts or testimonials) | “Something like, ‘Out of a patient population study of ten thousand people, this is what worked for them, this is what their opinions are, here’s some patient testimonies if you click this link.’” [R11] |

| User response | Prompts or questions from the application requiring a user reply, 2-way communications, or other forms of user input (e.g., logging activity, journaling) | “If there was an app, and it asked, ‘Did you eat at least three of these fifteen things today?’ You could say, ‘Yes, I did, I ate four of them.’ ‘Well, good job, you’re doing good! Bloodwork should be looking better.” [R11] |

| Benefit 3: Individualized guidance in SCD management | ||

| Annotation | Ability to annotate (highlight, take notes, “mark up”) guidelines within the application | “I could read through it and highlight important information so I could keep it in my memory.” [R20] |

| Choices | Application helps a user exercise choices from a set of options in planning his/her care, or supports user agency or control over his/her health care | “The guideline shows you who should and shouldn’t do something. You could relate that to yourself and say, ‘I really need to take this.’ Or you could just be like, ‘I don’t have any of these problems, so why am I taking hydroxyurea?’” [R30] |

| Context | Application helps a user understand his/her own care plan in the context of what is supported in academic literature, done by other SCD clinicians, or effective for other individuals with SCD | “They should show us the research of how effective hydroxyurea is. As a doctor, they can tell us the medicine works, but […] we don’t have any studies to show that it helped other people or reviews from people that took it and told us how well the hydroxyurea worked.” [R24] |

| Personalization | Personalization of a platform (tailored, or able to be tailored, to user traits) either built into its design and/or function, or available as options for a user to customize for him/herself | “Depending on where you fall at on the guidelines, give me information that conforms to me. Stuff like, having an infant who’s nine months old and whether to give them hydroxyurea, that doesn’t apply to me. Show me information that relates to me.” [R05] |

| Benefit 4: Rewards for guideline adherence | ||

| Gamification | Gaming elements, such as competition among users or point systems, to reinforce application use, or guideline adherence | “Make it more easier, more fun, to want to use the laptop or the computer or the phone. Maybe like a game or something.” [R32] |

| Health outcomes | Application recommends and supports actions that improve user health outcomes as a result of adherence (e.g., reduce symptom burden, prevent, or treat complications) | “It could benefit your body, it could benefit your longevity to take care of your body more, you know? Not to die, not be in pain.” [R29] |

| Incentives | Material incentives or rewards for using the application or adhering to the guidelines | “Everybody could use rewards: money rewards, gas card, or food. Those are the three things that people struggle with. It’ll make somebody want to follow what the guidelines say.” [R24] |

| Punishment | Punishments or negative consequences if guideline recommendations are not met | “[If guidelines are not met] it cost more in insurance.” [R27] |

| Barrier 1: Poor quality information on guidelines application | ||

| Advanced-level content | Guidelines are provided at an advanced reading level or with professional jargon that is not understandable for a user | “Making sure they don’t use such big words. If they’ve got 15 letters in it, more than likely I’m not going to try and figure it out. I might Google it but … Yeah. They’re going to have to find some dumbed-down terms to use for some of this stuff.” [R07] |

| Information overload | Too much information or too many alerts, causing a user to feel overwhelmed or overburdened | “If you send me a 10 to 15-page PDF, I’d probably read the first three, and if I don’t see what I need, I won’t read it. It needs to be short, simple, and to the point.” [R33] |

| Incomplete information | Guideline information is incomplete or insufficient (e.g., stating guidelines, but not explaining their basis or benefits) | “Just telling me to take it and not explaining to me the benefits or how it would help me.” [R24] |

| Poor organization | Information is presented in a format that does not provide the right information in the right time, context, or format to fit the user’s needs or preferences | “If the guidelines are not organized, then they’re hard to follow. If I’m in pain, If I have to sit here for 20 minutes looking for a guideline, I’m probably not going to look for it. I’ll just do what I know to do, which may not always be the best thing to do.” [R34] |

| Barrier 2: Inadequate stimulus to act upon guidelines | ||

| Inadequate cues to action | Application does not generate sufficient user interest or motivation to complete guideline recommendations, or provides recommendations that users are unwilling to do |

|

| Inapplicable to user | Non-use of application or its guideline recommendations due to perceptions that population-level guidelines are not applicable, effective, or relevant to an individual user |

|

| Incentive gaming | Opposition to rewards for guideline adherence because incentives are prone to lying or misrepresentation | “My thing with the rewards, how do you know if it’s really being followed? People will say, ‘I took my meds,’ and then come to find out, no you’re not doing this.” [R20] |

| Barrier 3: External limitations to fulfillment of guidelines | ||

| Busy/other obligations | User’s other obligations besides SCD care (e.g., work, family life) limit time or attention for application use or guideline completion |

|

| Inaccessible application | Application is difficult to access or use due to technical barriers (e.g., difficulties in accessing or using requisite technologies) |

|

| Inadequate means to meet guidelines | Inability to adhere to guidelines because means to complete tasks are not available or accessible to a user | “If they couldn’t afford the medicine. If they’re not someone who is able to take the medicine, […] you’re not able to get good data back, because they may not be able to afford it.” [R10] |

| Interaction with others (negative) | Reluctance to involve other individuals in SCD care or to discuss SCD with others | “I don’t really like talking about sickle cell, so having somebody else knowing and stuff is annoying.” [R48] |

| Patient-clinician conflict | User belief that guideline information may raise tension between the user and his/her SCD clinicians, or strain the patient-clinician relationship | “I might be an annoying patient to my doctor because I’m well-informed now. I will take up more time asking questions that might not be relevant to my care.” [R06] |

Benefit 1: Increased knowledge of disease and management strategies. Respondents anticipated that a guidelines application would augment their knowledge of SCD, including relevant aspects of its pathophysiology, signs/symptoms, treatment, health maintenance, and potential complications. Users requested information in understandable language [R17] and a format they could easily access and use [R22, R28], reasoning that improved knowledge of SCD and the biomedical basis of symptoms or self-care actions would strengthen motivation or self-efficacy for guideline fulfillment. In addition to using information for their own education, participants also wanted to share information to educate caregivers or clinicians who may be unfamiliar with the guidelines [R20, FG].

Benefit 2: Activation and instruction for self-care. Respondents expressed support for an application to inform and reinforce their SCD care through behavioral cues for instruction [R07, FG], encouragement [R01], and self-tracking or activity monitoring [R11]. They also wanted an application to incorporate interaction with supportive individuals, like clinicians [R33], caregivers [R13, FG], or other individuals with SCD [R11]. Users felt access to guidelines, paired with technology-enabled features like notifications or social interactions, would offer guidance, motivation, and support for adherence.

Benefit 3: Individualized guidance in SCD management. Individuals with SCD anticipated that a guidelines application would support their autonomy and agency in SCD care planning, allowing them to understand their options for treatment and health maintenance interventions and make decisions with their clinician [R30]. They could then validate their clinician’s advice in the context of academic literature or consensus standards of care [R24], and personalize application settings, like preferred information formats or reinforcing strategies, to execute those decisions [R20, R05]. These advantages were projected to reinforce adherence to care and empower users to be active participants, rather than passive recipients, in their care.

Benefit 4: Rewards for guideline adherence. Respondents supported instituting rewards for fulfilling guideline-derived objectives. Proposed incentives included material benefits [R24]; gamification elements, like points systems or competitions [R23]; expected health improvements from application use and guideline adherence [R29]; or negative consequences for nonadherence [R27]. Notably, a subset of respondents expressed firm opposition to material rewards, stating that health status, rather than incentives, ought to be a sufficient standalone motivator of application use and guideline adherence. These strong, yet polarized responses, underscore that applications must be tailored to individuals’ preferences.

Barrier 1: Poor quality information on guidelines application. Participants, particularly after seeing the full-text SCD guidelines, recognized that their jargon, text-heavy format, and length would be a barrier to layperson use [R07, R33]. Other barriers cited to understanding and using the application’s information included alert fatigue from contextually inappropriate behavioral cues or informational prompts, poor organization of guidelines content [R34], and inadequate details on the guidelines [R24].

Barrier 2: Inadequate stimulus to act upon guidelines. Another barrier to application use was an insufficient stimulus to motivate health behaviors. Examples included providing inadequate cues to action to generate user attention or interest [R21, R29]; recommending actions that users might perceive as inapplicable or ineffective for themselves [R07, R35, R41]; or incentive schemes that users could manipulate to obtain rewards without following guidelines [R20]. Therefore, even if the user was provided adequate information, the application might not elicit sufficient motivation to convert information into actions.

Barrier 3: External limitations to fulfillment of guidelines. The final user-proposed barrier was the possibility of external deterrents or constraints preventing adherence to guidelines. If a user had limited ability to undertake the recommended actions (e.g., caregiving obligations, transportation difficulties, low income) [R43, FG, R10]; lacked the technology access or fluency required to use an application [R29]; or was reluctant to discuss the guidelines with others [R48, R06], then restrictions beyond the application might still prevent guideline use or adherence.

Many Individuals with SCD use Technologies for General Purposes only, but Want to use These Technologies for Their Health

Self-identified current health-related uses of technology differed by technological modality (Table 3). Health uses of mobile apps and patient portals were primarily related to accessing information, like SCD educational materials or disease-relevant health news, and viewing or coordinating one’s own care, such as medications, appointments, test results, and personal health records. Text messaging was used for freeform communication with clinicians or caregivers and alerts or reminders about health-related actions (e.g., appointments or medication use, pickup, or refills). Social media and discussion forums were used to exchange information, experiences with illness and its care, and supportive messages with other individuals with SCD.

Table 3.

Current and Prospective Future Health Uses, and Barriers to Health Use, of Consumer Technologies Among Individuals with Sickle Cell Disease (N = 47)

| Current health uses | Prospective health uses | Concerns/barriers to health use |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile apps | ||

|

|

|

| Patient portal | ||

|

– |

|

| Text messaging | ||

|

|

|

| Social media | ||

|

|

|

| Discussion forums/groups | ||

|

|

|

For these uses that appear in both current and prospective use columns, some participants used them already, while others proposed them as a possible prospective use.

There were many prospective applications of technology to fulfill health-specific tasks or objectives (Table 3). Participants wanted to use mobile apps to look up disease-related information, receive reminders, communicate and track their health with their clinician, and engage in their care including filling out health related forms and scheduling medical appointments. Participant-suggested prospective uses for text messaging included an expanded range of informational messaging and timed alerts, and included motivational prompts to support self-care actions, patient education articles, or health tips. Prospective applications of social media and discussion forums included communication with clinicians or receipt of health news, educational materials, or self-care instructions. Interest in communication with one’s SCD clinician or caregivers was a consistent preference in current or prospective use across almost all modalities. Some uses (identified by an asterisk) were identified as both current and prospective uses, potentially reflecting differing awareness or adoption of currently available uses among respondents.

Concerns or deterrents to health-related technology use were similar across modalities (Table 3). These included lack of interest in the technology, inability to identify use cases, and preference for face-to-face or synchronous communication. Additional modality-specific concerns or barriers included technical difficulties with patient portal access or use; perception of text messaging and social media as “unprofessional” methods of communication with a clinician; and, for social media and discussion forums, concerns about information credibility, relevance, and privacy.

Discussion

This study is one of the first to describe a lack of awareness of clinical practice guidelines among individuals with chronic disease; desire to access such guidelines; and preferences for an application to adapt clinician-oriented clinical practice guidelines into a patient-centered format conducive to adherence. Most patients in this study were not aware that relevant guidelines existed, but once informed, expressed strong interest in receiving and using them. We examined patients’ preferred features in a guidelines application, the benefits they would want to receive from a guideline-based application, and the barriers that might limit application use or guideline adherence. These findings can guide development of an SCD guidelines application and potentially inform comparable technologies for other chronic conditions. This study further explored use, willingness to use, and barriers to adoption of different technology platforms for health-related purposes in this vulnerable population, which can further inform the design of technologies to deliver guidelines to patients.

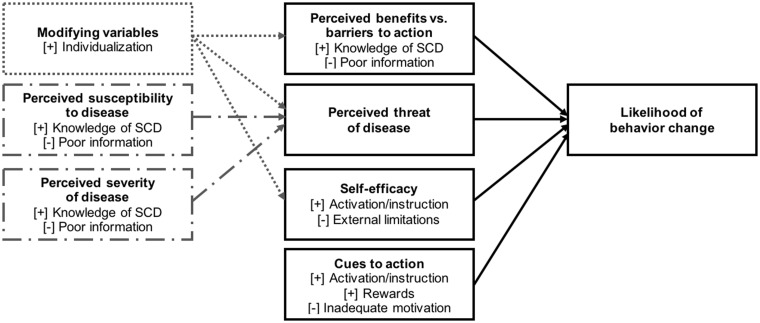

The framework of the HBM helped identify benefits, barriers, and attributes about a guideline-based application (Figure 2). Individuals with SCD expressed interest in an intervention that would provide information about the SCD guidelines, including the actions that individuals with SCD should take; the benefits of guideline adherence and subsequent health implications for the user (benefits of and barriers to action); and the likelihood (susceptibility) and burden (severity) of SCD complications. Respondents expressed a preference for instructional or motivational alerts, interactions with clinicians or caregivers, or interactive prompts for a user response (cues to action) that, collectively, translate awareness of guidelines into adherence to their recommendations (self-efficacy). In the HBM, health behaviors are influenced by modifying variables specific to each individual. Consistent with this tenet, respondents voiced a need for the guidelines application to provide personalized guidance and support choice of individuals with SCD in their care. These insights into individuals’ preferences reflect their habits and objectives for technology aids in SCD care, and are significant considerations to inform the design of a guideline-based application and other information technology applications for SCD management. Our recommendations for application design, derived from respondents’ preferences, are outlined in Table 4.

Figure 2.

Impact of guidelines application on user health behavior change, as conceptualized in the health belief model framework.

Table 4.

Recommendations for a Guideline Application for Chronic Disease Management Based on Participants’ Benefits-barriers Feedback

| Recommendation from participants | Examples |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

A user’s clinician has advised that she start iron chelation therapy. She references the guidelines for iron chelation, which include a link to connect to a social media application or community organization website. There, she can ask other patients about their experiences with this medication |

|

A user has an acute complication of SCD, like acute priapism. He selects this from a list of emergencies to notify his caregiver and clinician. The application advises him to go to an ER if it is prolonged, and shows him guidelines that he can share with an ER physician who might be unfamiliar with SCD care for priapism |

|

|

|

|

Other studies have described adaptations of evidence-based information to support education and disease management, such as “lay language” guideline versions or self-management information technologies, but have not explored how technology might improve access and utility of guidelines.35–37 We expand upon this work by exploring a technology adaptation of chronic disease clinical practice guidelines to support guideline awareness, adherence, and shared decision-making in a primarily vulnerable patient population. The qualitative findings in our study concur with patient-reported benefits of guideline access in previous studies, including accessing lay-friendly instructions; understanding and exercising options in disease management; informing patients to facilitate decision-making in partnership with clinicians; and offering a “second opinion” to validate their clinician’s guidance.35,38–44 Similarly, our identified barriers mirror potential challenges of patient-centered guidelines studied in other diseases and formats, like reluctance to question one’s clinician, disagreement with guidelines, or insufficient time or resources to implement guidelines.35,45 Our findings can be used to mitigate these barriers, which may be more pronounced in SCD due to socioeconomic barriers, mistrust of healthcare providers, and concerns regarding safety and efficacy of mainstay therapies.46–49 Additionally, respondents’ preferences for application design reflect common principles for design of chronic disease self-management applications (e.g., easily readable and accessible information, instructions and alerts for self-care actions, self-tracking or goal monitoring, motivational prompts or feedback, incentives or rewards, and interaction with support figures or clinicians).24,50–58 These findings suggest that a guidelines application, relative to conventional patient-centered guidelines, may be advantageous for leveraging technology features to make guidelines more engaging and interactive, and therefore potentially more impactful for use and adherence.

Another unique finding in our study is patients’ emphasis on shared decision-making and desire to use this guideline technology to educate others who may not know guidelines content, including clinicians with limited experience or training related to their condition (Tables 3 and 4). There are examples of clinicians not knowing or being comfortable with chronic disease guidelines.9,26 Informing patients about the most recent evidence may allow them to collaborate with clinicians and promote evidence-based care, but may also introduce challenging interactions if the clinician is unfamiliar with, or disagrees with, the guidelines. This new shared decision-making dynamic is an area that will require future research.

Our assessment of respondents’ current and prospective technology uses is consistent with prior studies in confirming that individuals with SCD report a strong desire to adopt new technologies or programs to support their health-related objectives and goals.24,59–62 Participants used technology for a variety of health purposes and had many ideas for potential uses, but also voiced concerns about technologies. They used some technologies for educational purposes, communication, exchanging experiences, self-management, and viewing or coordinating one’s own care, such as medications, appointments, test results, and personal health records. Participants had concerns about multiple technology platforms, including access, technical difficulties, and a lack of benefit. Social media applications for health produced more concerns than other technologies, primarily attributable to respondents’ privacy concerns and the perception of social media as a social or recreational tool, not a health or education resource (Table 3). These results showed current use and desire to use technology for their health in a variety of ages of individuals with SCD, including those who may not be as technology-savvy as the adolescents and young adults studied previously.24,62 This finding is particularly important in the context of recent improvements in life expectancy of individuals with SCD, as these technologies will, in the near future, support care for individuals with SCD of increasingly diverse ages and varied levels of technical literacy.

There were several limitations to this study. Our results were based upon a convenience sample from Tennessee and was complicated by a moderate rate of loss to follow-up; therefore, the technology usage and preferences of our sample may not be generalizable. These cautions were somewhat mitigated by the observation that our sample’s preferences for information technology in SCD care were consistent with those found in previous studies.24,62 In addition, individuals who do not follow up for research activities are likely those not adhering to guidelines, and all of these studies may underrepresent their perspectives. Furthermore, we were not able to evaluate the quantitative relationships between specific participant characteristics and technology usage or preferences due to a small study sample. However, this study’s main objectives were primarily descriptive and exploratory, intended to generate hypotheses, and it appropriately lays the groundwork for subsequent studies to confirm these hypotheses with tests of significance. Finally, our study relied on self-report measures of technology use and respondents’ perceptions of their technology needs; therefore, actual use characteristics or preferences may differ from those articulated in this study.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence that individuals with SCD, a chronic condition predominantly affecting a vulnerable population, have limited knowledge of clinical practice guidelines written for clinician use, but once informed, have strong interest in accessing and using such guidelines to manage their disease. Patients with SCD also exhibit interest in use of a patient-centered guideline application, with consistently desired features of easily accessible, actionable information to support decision-making; behavioral cues and alerts; interactions with caregivers and patient support networks; and personalization for individual traits or preferences. Preferences for some functions, such as rewards or social interactions, were more mixed, underscoring the necessity for a customizable application design. Patients also describe a desire to use these guidelines to educate clinicians who may not know as much about their disease. This new shift in the shared-decision making dynamic, in which patients sometimes know more than their clinicians, will need careful consideration and research to prevent strained patient-clinician relationships and deliver the best care for patients. As technologies continue to rapidly evolve, patients’ willingness to use innovative tools for disease management should be considered in application design. Our findings augment consumer health informatics literature by providing direction for future efforts to design a guideline application, or other information technologies that can engage and activate patients for disease management or shared decision-making.

Future studies might extend upon these results by incorporating the identified qualitative themes into subsequent interventions and evaluating user feedback or pilot trial outcomes. These findings could also be applied to guidelines applications in other chronic diseases—particularly, although not exclusively, conditions primarily affecting young and/or vulnerable populations. Likewise, subsequent research should build upon the descriptive foundations presented in this study to more precisely characterize the participant characteristics that predict certain types of technology use, or certain preferences for technology design, helping clinicians connect individuals with chronic disease with the technologies and features that best suit their personal needs, interests, and goals.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant number UL1TR000445.

Competing interests

None.

Contributors

TLM, LN, AAK, KB, DS, VMM, GPJ, MD, and RMC each made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work. AU, TLM, WA, and RMC each made substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data. AU, TLM, and RMC drafted the manuscript, and all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approve the final manuscript and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Human Subjects Protections

This study was performed in compliance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki on Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects, and was reviewed and approved by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center institutional review board.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Karina Wilkerson, Natalie Jordan, Jeannie Byrd, and Emmanuel Volanakis for their support of this study and assistance with enrollment.

References

- 1. Prevention CfDCa. Data & Statistics. Secondary Data & Statistics 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/data.html. Accessed December 10, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2010;38(4 Suppl):S512–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Steiner CA, Miller JL. Sickle Cell Disease Patients in U.S. Hospitals, 2004: Statistical Brief #21. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yusuf HR, Atrash HK, Grosse SD, Parker CS, Grant AM. Emergency department visits made by patients with sickle cell disease: a descriptive study, 1999–2007. Am J Prevent Med 2010;384:S536–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kauf TL, Coates TD, Huazhi L, Mody-Patel N, Hartzema AG. The cost of health care for children and adults with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol 2009;846:323–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yawn BP, Buchanan GR, Afenyi-Annan AN et al. Management of sickle cell disease: summary of the 2014 evidence-based report by expert panel members. JAMA 2014;31210:1033–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999;28215:1458–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cochrane LJ, Olson CA, Murray S, Dupuis M, Tooman T, Hayes S. Gaps between knowing and doing: understanding and assessing the barriers to optimal health care. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2007;272:94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mickan S, Burls A, Glasziou P. Patterns of ‘leakage’ in the utilisation of clinical guidelines: a systematic review. Postgrad Med J 2011;871032:670–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brandow AM, Panepinto JA. Hydroxyurea use in sickle cell disease: the battle with low prescription rates, poor patient compliance and fears of toxicities. Expert Rev Hematol 2010;33:255–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ware RE, Aygun B. Advances in the use of hydroxyurea. ASH Education Program Book 2009;2009(1):62–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hassell KL. Provider barriers to hydroxyurea use in adults with sickle cell disease: a survey of the Sickle Cell Disease Adult Provider Network. J Natl Med Assoc 2008;1008:968–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Candrilli SD, O'brien SH, Ware RE, Nahata MC, Seiber EE, Balkrishnan R. Hydroxyurea adherence and associated outcomes among Medicaid enrollees with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol 2011;863:273–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beverung LM, Brousseau D, Hoffmann RG, Yan K, Panepinto JA. Ambulatory quality indicators to prevent infection in sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol 2014;893:256–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Raphael JL, Shetty PB, Liu H, Mahoney DH, Mueller BU. A critical assessment of transcranial doppler screening rates in a large pediatric sickle cell center: opportunities to improve healthcare quality. Pediatric Blood Cancer 2008;515:647–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lanzkron S, Haywood C Jr, Segal JB, Dover GJ. Hospitalization rates and costs of care of patients with sickle-cell anemia in the state of Maryland in the era of hydroxyurea. Am J Hematol 2006;8112:927–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stettler N, McKiernan CM, Melin CQ, Adejoro OO, Walczak NB. Proportion of adults with sickle cell anemia and pain crises receiving hydroxyurea. JAMA 2015;31316:1671–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Asnani MR, Quimby KR, Bennett NR, Francis DK. Interventions for patients and caregivers to improve knowledge of sickle cell disease and recognition of its related complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;10:CD011175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fisher E, Law E, Palermo TM, Eccleston C. Psychological therapies (remotely delivered) for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;3:CD011118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eccleston C, Palermo TM, Williams AC et al. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;5:CD003968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dampier C, Ely E, Brodecki D, O'Neal P. Home management of pain in sickle cell disease: a daily diary study in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2002;248:643–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Frost JR, Cherry RK, Oyeku SO et al. Improving Sickle Cell Transitions of Care Through Health Information Technology. Am J Prev Med 2016;51(1 Suppl 1):S17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yoon SL, Godwin A. Enhancing self-management in children with sickle cell disease through playing a CD-ROM educational game: a pilot study. Pediatr Nurs 2007;331:60–3, 72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crosby LE, Ware RE, Goldstein A et al. Development and evaluation of iManage: a self-management app co-designed by adolescents with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;641:139–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lunyera J, Jonassaint C, Jonassaint J, Shah N. Attitudes of primary care physicians toward sickle cell disease care, guidelines, and comanaging hydroxyurea with a specialist. J Prim Care Community Health 2016;81:37–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shook LM, Farrell CB, Kalinyak KA et al. Translating sickle cell guidelines into practice for primary care providers with Project ECHO. Med Educ Online 2016;211:33616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rosenstock IM. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ Monographs 1974;24:354–86. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ogden J. Health Psychology. McGraw-Hill Education: Maidenhead, Berkshire, UK; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Katikiro E, Njau B. Motivating factors and psychosocial barriers to condom use among out-of-School Youths in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: a Cross Sectional Survey using the health belief model. ISRN AIDS 2012;2012:170739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hung M, Conrad J, Hon SD, Cheng C, Franklin JD, Tang P. Uncovering patterns of technology use in consumer health informatics. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Stat 2013;56:432–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;422:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;159:1277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Corbin JM, Strauss A. Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual Sociol 1990;131:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 34. MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Kay K, Milstein B. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. CAM J 1998;102:31–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Loudon K, Santesso N, Callaghan M et al. Patient and public attitudes to and awareness of clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review with thematic and narrative syntheses. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McDougald Scott AM, Jackson GP, Ho YX, Yan Z, Davison C, Rosenbloom ST. Adapting comparative effectiveness research summaries for delivery to patients and providers through a patient portal. AMIA… Annual Symposium Proceedings. AMIA Symposium 2013;2013:959–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Santesso N, Rader T, Nilsen ES et al. A summary to communicate evidence from systematic reviews to the public improved understanding and accessibility of information: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Epidemiol 2015;682:182–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. van der Weijden T, Pieterse AH, Koelewijn-van Loon MS et al. How can clinical practice guidelines be adapted to facilitate shared decision making? A qualitative key-informant study. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;2210:855–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fearns N, Kelly J, Callaghan M et al. What do patients and the public know about clinical practice guidelines and what do they want from them? A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Quintana Y, Feightner JW, Wathen CN, Sangster LM, Marshall JN. Preventive health information on the Internet. Qualitative study of consumers' perspectives. Can Fam Physician 2001;47:1759–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fearns N, Graham K, Johnston G, Service D. Improving the user experience of patient versions of clinical guidelines: user testing of a Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN) patient version. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dykes PC, Currie L, Bakken S. Patient Education and Recovery Learning System (PEARLS) pathway: a tool to drive patient centered evidence-based practice. J Healthc Inf Manag 2004;184:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Patel VL, Branch T, Mottur-Pilson C, Pinard G. Public awareness about depression: the effectiveness of a patient guideline. Int J Psychiatry Med 2004;341:1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Buhse S, Muhlhauser I, Heller T et al. Informed shared decision-making programme on the prevention of myocardial infarction in type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2015;511:e009116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lingner H, Burger B, Kardos P, Criee CP, Worth H, Hummers-Pradier E. What patients really think about asthma guidelines: barriers to guideline implementation from the patients' perspective. BMC Pulm Med 2017;171:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians' perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med 2000;506:813–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lattimer L, Haywood C Jr, Lanzkron S, Ratanawongsa N, Bediako SM, Beach MC. Problematic hospital experiences among adult patients with sickle cell disease. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2010;214:1114–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Elander J, Beach MC, Haywood C Jr. Respect, trust, and the management of sickle cell disease pain in hospital: comparative analysis of concern-raising behaviors, preliminary model, and agenda for international collaborative research to inform practice. Ethn Health 2011;16(4–5):405–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Badawy SM, Thompson AA, Liem RI. Beliefs about hydroxyurea in youth with sickle cell disease. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.hemonc.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Slater H, Campbell JM, Stinson JN, Burley MM, Briggs AM. End user and implementer experiences of mHealth technologies for noncommunicable chronic disease management in young adults: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2017;1912:e406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Davis SR, Peters D, Calvo RA, Sawyer SM, Foster JM, Smith L. “Kiss myAsthma”: Using a participatory design approach to develop a self-management app with young people with asthma. J Asthma 2017:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Peters D, Davis S, Calvo RA, Sawyer SM, Smith L, Foster JM. Young people's preferences for an asthma self-management app highlight psychological needs: a participatory study. J Med Internet Res 2017;194:e113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Geryk LL, Roberts CA, Sage AJ, Coyne-Beasley T, Sleath BL, Carpenter DM. Parent and clinician preferences for an asthma app to promote adolescent self-management: a formative study. JMIR Res Protoc 2016;54:e229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cafazzo JA, Casselman M, Hamming N, Katzman DK, Palmert MR. Design of an mHealth app for the self-management of adolescent type 1 diabetes: a pilot study. J Med Internet Res 2012;143:e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Holtz BE, Murray KM, Hershey DD et al. Developing a patient-centered mHealth App: a tool for adolescents with type 1 diabetes and their parents. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;54:e53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hilliard ME, Hahn A, Ridge AK, Eakin MN, Riekert KA. User preferences and design recommendations for an mHealth app to promote cystic fibrosis self-management. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2014;24:e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Waite-Jones JM, Majeed-Ariss R, Smith J, Stones SR, Van Rooyen V, Swallow V. Young people's, parents', and professionals' views on required components of mobile apps to support self-management of juvenile arthritis: qualitative study. JMIR mhealth Uhealth 2018;61:e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stinson JN, Lalloo C, Harris L et al. iCanCope with pain: user-centred design of a web- and mobile-based self-management program for youth with chronic pain based on identified health care needs. Pain Res Manag 2014;195:257–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Shah N, Jonassaint J, De Castro L. Patients welcome the Sickle Cell Disease Mobile Application to Record Symptoms via Technology (SMART). Hemoglobin 2014;382:99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jonassaint CR, Shah N, Jonassaint J, De Castro L. Usability and feasibility of an mhealth intervention for monitoring and managing pain symptoms in sickle cell disease: The Sickle Cell Disease Mobile Application to Record Symptoms via Technology (SMART). Hemoglobin 2015;393:162–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Estepp JH, Winter B, Johnson M, Smeltzer MP, Howard SC, Hankins JS. Improved hydroxyurea effect with the use of text messaging in children with sickle cell anemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;6111:2031–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Badawy SM, Thompson AA, Liem RI. Technology access and smartphone app preferences for medication adherence in adolescents and young adults with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016;635:848–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]