Abstract

Increasing evidence-based practice (EBP) use in community mental health is a national priority, especially given that one in five youth will suffer from mental health concerns before adulthood. Implementation science offers a unique lens for understanding EBP use that identifies barriers and facilitators of successful adoption. Consumer engagement is often overlooked as an EBP implementation strategy. In this article, we describe the State of Hawai‘i Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division's innovative effort to target consumer EBP demand via the Help Your Keiki Website. Feedback from community stakeholders and website analytics converge to suggest that the most helpful content is related to finding help, normalizing concerns, and questions to ask therapists. Future outreach efforts as well as ongoing improvement and enhancement of the website are discussed.

Background

Caregivers of youth with emotional and behavioral concerns often face many challenges. Are my child's difficulties different than other youth with similar concerns? Where do I find the right services for my child? How will I know if these services are working? What happens if I do not agree with the service recommendations from the numerous professionals on my child's treatment team? What if my child does not get better? A common theme that emerges from these concerns is caregiver's uncertainty and lack of control over the decisions in their child's life.

Research has demonstrated that while many psychosocial treatments have been developed and tested, youth often do not receive treatments that are informed by evidence.1 Evidence-based practice (EBP) is defined as the integration of the best research evidence, clinical experience and expertise, and patient values and preferences.2 Systematic efforts to increase the use of EBPs have helped to develop implementation science specifically in this area, which focuses on how an EBP is adopted and used within a service setting.3 There is emerging evidence that EBP implementation occurs across many contexts that includes organizations, therapists, and consumers.4

Borrowing from the field of marketing science, one area of youth EBP implementation science that has received increased attention is creating consumer (ie, youth, family, and caregiver) demand for EBP.5–7 For example, Friedberg and colleagues7 provided recommendations for increasing caregiver mental health treatment awareness for youth and their families through expanding the field's social media presence, elaborate marketing, branding, and direct-to-consumer marketing. Furthermore, studies have begun to accumulate consumer perspectives on the term EBP, and findings have suggested that youth and caregivers are unfamiliar with and have negative perceptions of the term EBP.8,9 Taken together, these studies elucidate a need for careful language and innovative marketing strategies to increase consumer EBP demand.

Development of the Help Your Keiki Website (www.helpyourkeiki.com)

The State of Hawai‘i Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division (CAMHD) created the Help Your Keiki (HYK) website (see Figure 1) to provide EBP information to youth and families. Development began in 2009 with the formation of the Help Your Keiki subcommittee within the CAMHD Evidence-Based Services (EBS) Committee, an interdisciplinary task force committed to the dissemination and implementation of EBPs within the system. The larger committee and subcommittee were comprised of various stakeholders including parent partners from Child and Family Service (CFS), Hawai‘i Families as Allies (HFAA), and the Special Parent Information Network (SPIN), CAMHD's Clinical Services Office and the Research, Evaluation, and Training team, the Department of Education (DOE), and the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa's Department of Psychology. Over the course of two years, meetings were held at least once per month to develop site content, while placing a strong emphasis on the caregiver perspective on psychosocial treatments in language accessible to youth and families.

Figure 1.

Help Your Keiki Website

Defining EBP

The HYK website content was consistent with CAMHD's innovative efforts to conceptualize EBP at both the package level (ie, treatments with similar theoretical foundations that share a majority of treatment components) and at the element level (ie, discrete clinical techniques or strategies used as a part of a larger treatment).10 Specifically, the website heavily publicized two technical reports: Chorpita and Daleiden's11 “CAMHD Biennial Report: Effective Psychosocial Interventions for Youth with Behavioral and Emotional Needs” (http://helpyourkeiki.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/2009-Biennial-Report.pdf) and the American Academy of Pediatrics12 “Evidence-Based Child and Adolescent Psychosocial Interventions” (https://www.practicewise.com/portals/0/forms/PracticeWise_Blue_Menu_of_Evidence-Based_Interventions.pdf).

Based on the findings from these larger reports at both the package and element level, parent partners facilitated subcommittee efforts to distill the most relevant information for youth and families. Rather than reporting on all the packaged treatments and elements within each report, the subcommittee chose to highlight the top five elements and top three packaged treatments per problem area (eg, anxiety, depression, attention/hyperactivity, disruptive behavior). Parent partners advocated for only reporting on approximately eight overall treatment approaches to reduce the potential for caregiver confusion in the face of an overabundance of information (eg, for the problem area of anxiety, treatment recommendations were reduced from 54 to eight).

Consumer Adaptation

Parent partners further advocated for youth- and caregiver-friendly language that were reflective of Hawai‘i culture. Specifically, they noted that the terms “packaged treatments” and “elements” were not particularly parent-friendly. They suggested using the headings (a) Keiki skills (coping skills for children), (b) Parent Tools (skills parents, caregivers, or therapists can use to support a youth), and (c) Treatments that Work (packaged treatments). The subcommittee also worked closely with parent partners collaboratively to translate any text that parent partners felt were too much like jargon and not easily understood. The title of the website itself, with its explicit use of the word “keiki” (the Hawaiian word for child or children, used as part of everyday speech in Hawai‘i) is an outgrowth of parent partner input.

Additionally, parent partners and other subcommittee members created a shared vision and mission for the HYK website. For example, parent partners noted that the single focus of promoting EBP was too narrow and did not address the many needs of youth and families. As a result of this discussion, additional resources were developed such as (a) What to expect with a good therapist (eg, “Provides updates throughout the course of therapy”), (b) Questions to ask your child's therapist (eg, “How will you monitor her progress?”), (c) Helpful Websites/More Resources, and (d) Finding help (how to look for treatment services). In more recent years, the EBS Committee has continued its grassroots effort to maintain and update the HYK website in a variety of ways, such as outreach via several social media outlets. One example includes the creation of the HYK Instagram page (https://www.instagram.com/helpyourkeiki) to promote local activities (eg, Children's Mental Health Awareness Day), recent research findings, and current events (eg, see Figure 2, dealing with unresolved trauma). Consistent with efforts to disseminate the latest research findings, quarterly roundtable discussions on local EBP-related efforts (eg, “Usage and Outcomes of Exposure Therapy in the CAMHD System”) are sponsored by the EBS Committee, open to the public for attendance, and are archived on the HYK website.

Figure 2.

Help Your Keiki Instagram Post

Reach, Penetration, and Feedback

Cyclical advertising and outreach efforts thus far have taken place across a variety of mediums. For example, an HYK flyer has been distributed at numerous state conferences (eg, SPIN, Hawai‘i Psychological Association, Institute on Violence, Abuse, and Trauma) and the website continues to be introduced to parents during clinical intake meetings (eg, families receive an HYK flyer upon enrolling for CAMHD services, Center for Cognitive Behavior Therapy clinical staff members share the website with parents at intake). HYK flyers are readily available to parents of all DOE youth through their school's Student Services Coordinator.

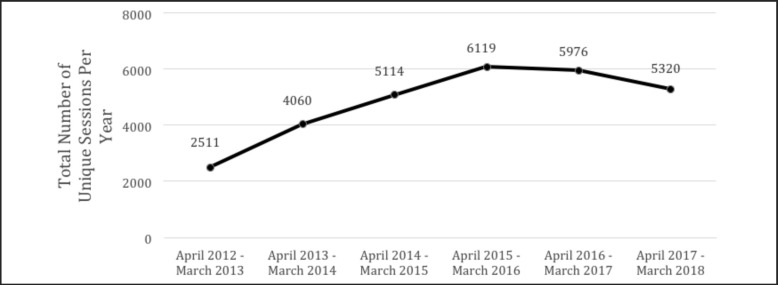

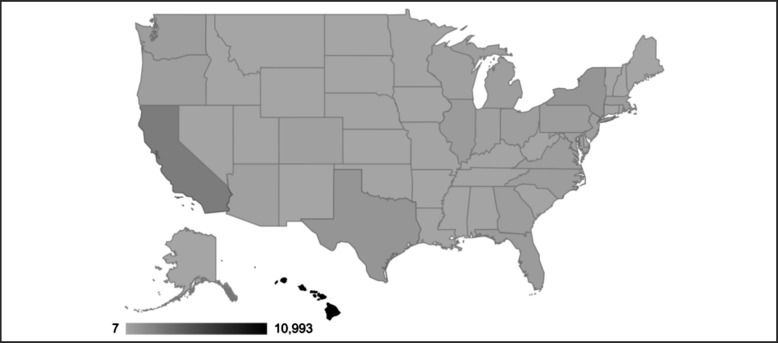

Since the HYK launch in April 2012, reach and penetration have been monitored to help inform targeted promotion strategies within the CAMHD system and larger State of Hawai‘i. Reach is defined as the number of sessions (ie, visits) to the website by a unique user and penetration as the geographical regions where visits originated. As of April 2018, the HYK website has had a total of 29,100 unique user visits across six years (see Figure 3). Globally over the past six years, the HYK website received visits from 150 different countries (see Figure 4) including the United States (n = 23,177 sessions, 79.65%), United Kingdom (n = 818 sessions, 2.81%), Canada (n = 737 sessions, 2.53%), Brazil (n = 513 sessions, 1.76%), and India (n = 392 sessions, 1.35%). Within the United States, the HYK website had visitors from all 50 states (see Figure 5) including Hawai‘i (n = 10,993 sessions, 47.43%), California (n = 2,291 sessions, 9.88%), New York (n = 863 sessions, 3.72%), Texas (n = 746 sessions, 3.22%), and Illinois (n = 563, 2.43%). Within Hawai‘i, the HYK website had visitors from four of the five counties (except Kalawao county) and six of the seven major Hawaiian Islands (except Ni‘ihau) which spanned 66 different cities including Honolulu (n = 6,974 sessions, 63.44%), Hilo (n = 826 sessions, 7.51%), Mililani (n = 507 sessions, 4.61%), Kailua-Kona (n = 244 sessions, 2.22%), and Kaneohe (n = 223 sessions, 2.03%).

Figure 3.

Help Your Keiki Website Unique Sessions per Year

Figure 4.

Help Your Keiki Website Global Penetration (April 2012 – March 2018)

Figure 5.

Help Your Keiki Website United States Penetration (April 2012 – March 2018)

Additionally, feedback from community stakeholders including CAMHD consumers, contracted providers, and staff have been critical for ongoing improvement efforts. For example, the 2017 CAMHD consumer surveys indicate that a majority of CAMHD caregivers (n = 138, 75.5%) were not aware of the HYK website. To address this concern, the EBS Committee has been actively soliciting feedback from direct service providers and parent partner organizations. Feedback has suggested that the most helpful resources on the HYK website are the common problems pages, which help to normalize youth mental health concerns, and the how to find help page, which goes through a step-by-step process for finding help. Consistent with this feedback, website analytic data indicated that visitors spend the most time on the questions to ask your therapist (average time = 5.05 minutes), finding help for your keiki (average time = 34 seconds), and common problems (average time = 31 seconds) pages. Additionally, areas of improvement have been identified including reducing the amount of text, keeping content up to date, improving navigation, and increasing return visits for youth and families. As a result, areas for future development may include providing examples (eg, videos) of keiki and parent skills and developing a list of natural support groups for caregivers of youth who have similar concerns.

Discussion and Future Directions

The goal of the HYK website is to increase consumer awareness of EBP using direct-to-consumer marketing to increase EBP demand. The HYK website represents a shared commitment toward promoting and empowering caregivers to advocate for the best treatments for youth with emotional and behavioral concerns. Data on reach and penetration suggest that the HYK website has garnered attention both locally, nationally, and globally. Further evidence is the promotion of the HYK website on national websites like the American Psychological Association's Society for Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. HYK website maintenance and expansion efforts continue to proliferate as the CAMHD EBS Committee updates the website with the latest EBP findings, coordinates quarterly roundtable presentations, and creates weekly Instagram posts to promote best practices in youth mental health. It is hoped that the HYK website will help youth and caregivers to demand EBPs in their mental health treatment, thereby creating some pressure for therapists to consider and eventually utilize such practices. Future evaluations of the HYK website may wish to examine actual behavior changes in therapist adoption and consumer demand of EBP. The HYK website also represents a reminder to all professionals to be mindful of the consumer in our shared work within the State of Hawai‘i and beyond.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the State of Hawai‘i Department of Health Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division's Evidence-Based Services Committee and the Help Your Keiki subcommittee. We also extend our sincerest appreciation to the youth and families that we serve.

Contributor Information

Tetine L Sentell, Office of Public Health Studies at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa.

Donald Hayes, Hawai‘i Department of Health.

References

- 1.Kazdin AE, Blasé SL. Rebooting psychotherapy research and practice to reduce the burden of mental illness. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6(1):21–37. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychological Association, author. Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice. Evidence-based practice in psychology. American Psychologist. 2006;61(4):271–285. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Welcome to implementation science. Implementation Science. 2006;1(1):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009;4(1):50–65. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker SJ. Direct-to-consumer marketing: A complementary approach to traditional dissemination and implementation efforts for mental health and substance abuse interventions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2015;22(1):85–100. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedberg RD, Bayar H. If It Works for Pills, Can It Work for Skills? Direct-to-Consumer Social Marketing of Evidence-Based Psychological Treatments. Psychiatric Services. 2017;68(6):621–623. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedberg RD, Nakamura BJ, Winkelspect C, Tebben E, Miller A, Beidas RS. Disruptive Innovations to Facilitate Better Dissemination and Delivery of Evidence-Based Practices: Leaping Over the Tar Pit. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2018;3(2):57–69. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker SJ, Spirito A, Vanmali R. Perceptions of ‘evidence-based practice’ among the consumers of adolescent substance use treatment. Health Education Journal. 2016;75(3):358–369. doi: 10.1177/0017896915581061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okamura KH, Skriner LC, Becker-Haimes EM, Adams DR, Becker S, Kratz HE, Jackson K, Berkowitz S, Zinny A, Cliggitt L, Beidas RS. Perceptions of evidence-based practice among consumers receiving Trauma Focused-Cognitive Behavior Therapy. Child Maltreatment. Under review. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chorpita BF, Becker KD, Daleiden EL. Understanding the common elements of evidence-based practice: Misconceptions and clinical examples. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(5):647–652. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318033ff71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL. Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):566–579. doi: 10.1037/a0014565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Academy of Pediatrics Evidence-Based Child and Adolescent Psychosocial Interventions. [June 1, 2018]. https://www.practicewise.com/portals/0/forms/PracticeWise_Blue_Menu_of_Evidence-Based_Interventions.pdf.