Abstract

Aim:

The aim of the present study is to compare the amount of remaining calculus, loss of tooth substance, and roughness of root surface after scaling and root planing with or without magnification loupes using scanning electron microscope.

Materials and Methods:

In the study, 30 teeth indicated for extractions due to severe chronic generalized periodontitis were included in the study. In test Group I, scaling and root planing was performed without magnification loupes, and in test Group II, scaling and root planing was performed with magnification loupes before extraction. In control Group III, no procedure was performed. After scaling and root planing, teeth were extracted followed by preparation of specimens. Specimens were then sent for scanning electron microscope study.

Results:

Statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05) differences were found among different test groups. Results showed that test Group II with magnification loupes had less remaining calculus and smoother surface with lesser amount of loss of cementum layer.

Conclusion:

From this, it was concluded that test Group II was more efficient in root debridement than test Group 1, so scaling and root planing done with magnification loupes will cause less damage to the tooth surface.

Key words: Magnification, magnification loupes, root planing, scaling, scanning electron microscope

INTRODUCTION

The main players of periodontal diseases are an array of various periodontal pathogens that initiate an ensemble host immune inflammatory response which ultimately leads to the bone loss and attachment loss. The goal of periodontal therapy intends to alter or remove the microbial environment and contribute risk factors for periodontitis, so as to apprehend the progression of the disease and maintain the dentition in health and function with appropriate esthetics.[1] Scaling and root debridement as a treatment plan for periodontitis is one of the most commonly employed conservative procedures and is still considered as “gold standard” therapy.[2]

The traditional protocol of nonsurgical periodontal therapy includes visor procedure as closed scaling and root planing is done in a quadrant- or sextant-wise approach that is normally completed within 4–6 weeks.[3] The ultimate motive of therapeutic intervention is to get rid of the existing bacteria in the biofilm and dental calculus, from the root surface.[4] Conventionally, vigrous approach by scaling and root planing with curettes was advocated to eliminate tenacious deposits and endotoxins from root surface. Conversely, the present investigations noticeably demonstrated that endotoxins attach poorly to root surfaces and thus gently debriding the root surface could possibly lead to root detoxification without substantial cementum removal. However, the present evidence in relation to probable consequential adverse effects, inclusive of loss of root substance and roughness after root planing with manual as well as ultrasonic instruments, still remain undetermined.[5] Published in vivo studies have demonstrated a favorable relationship between root surface roughness and the aggregation of supra- and sub-gingival plaque. Consistent with this, numerous animal studies have exhibited a higher extent of periodontitis and more bacterial colonization on rougher subgingival root surfaces. Thus, thorough understanding of the outcomes of various treatment modalities on the topography of the root surface may hence be deemed necessary.[6,7]

Till date, numerous instruments for scaling and root planing have evolved that includes both manual and power-driven devices. However, numerous studies have shown that absolute removal of embedded bacterial deposits on the root surface and occurring inside the periodontal pockets with detailed nonsurgical instrumentation by visual inspection is not inevitably accomplished. Furthermore, it is difficult to reach areas such as furcations, mesial or distal concavities/grooves, and distal sites of molars.[8] However, to accomplish this, there is a need for advanced clinical skills that can be achieved by root planing with the help of magnification loupes.

Development in the therapies and techniques such as micro ultrasonics and endoscopes, lasers, magnification loupes, and dental operating microscopes offers advantages to the clinician such as illumination, magnification, visual acuity, and increased precision in the delivery of operating skills. Intended primarily to improve the visual acuity of practitioners, magnification is promulgated to maintain the balanced clinical posture. Published reports have demonstrated that the use of magnification lenses improved the precision in instrumentation and facilitate optimal visualization of the oral cavity.[9]

Despite the above positive outlook, there are insufficient and inconsistent data available in the literature regarding the use of magnification loupes and to assess the effectiveness using scanning electron microscope for performing scaling and root planing. Hence, the present study was done to evaluate the efficacy of supra- and sub-gingival scaling and root planing with and without the use of magnification loupes by scanning electron microscope.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study included 30 extracted teeth from the patients within the age group of 25–70 years. Ethical clearance was taken from Institutional Ethics and Review Board. Patients were explained about the procedure to be performed and an informed consent was taken. Detailed medical and dental history of all the patients was taken. The inclusion criteria comprised patients with good general health suffering from periodontitis, caries-free teeth, and single-rooted teeth scheduled for extraction having ≥5 mm of clinical attachment loss having only Miller's Grade I and Grade II mobility. The patients who were medically compromised or with endodontically involved teeth, pregnant/lactating women, and who had undergone any periodontal therapy in the past 6 months were excluded from the study. All the procedures in the present study were done by the main investigator to eliminate interoperator variability and to minimize variations in factors as length of stroke, amount of pressure, and force applied during instrumentation.

A randomized control clinical study was done. The study design comprised three groups, namely, test Group I, test Group II, and control Group III. All the teeth were equally and randomly assigned into these three groups, so each group was comprised 10 teeth.

Test Group I: Unaided group (naked eye procedure)

Test Group II: Aided group (procedure performed with the help of magnification loupes)

Control Group III (no procedure performed).

In test Group I, manual scaling and root planing was performed without any visual aid (unaided) on the randomly selected interproximal tooth surface in a single session with a set of Gracey curettes (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL, USA). The scaling was done until the test surface appeared smooth and clear by visual and tactile judgment. In test Group II, manual scaling and root planing was accomplished with Gracey curettes (Hu-Friedy) by means of magnification loupes of magnification (×2.5). In control Group III, no scaling and root planing was done. Only one interproximal surface (mesial or distal) per tooth was studied (30 tooth surfaces). No time limit was placed for the scaling and root planning.

Description of the procedure

A circumferential groove was marked on the selected tooth surface at the level of free gingival margin with a no. 2 round bur in using a high-speed handpiece with copious water irrigation. The groove provided a landmark for future microscopic reference for evaluation of the subgingival root surface for all the groups. Scaling and root planing was then performed in the groups as described above followed by extraction of particular tooth under local anesthesia with forceps placed above the circumferential groove. During the extraction process, care was taken that root surface remains unaltered. The teeth were rinsed thoroughly under cold tap water and were brushed lightly with a soft toothbrush for about 1 min to remove any blood or food debris. Then, tooth was stored in 0.9% normal saline till the further procedure is carried out.

Preparation of tooth specimen for scanning electron microscope study

All the 30 teeth were sagittally sectioned using micromotor handpiece and disk bur. From circumferential groove, a marking point of 4 mm × 5 mm surface area was marked with a bur. Both test group and control group tooth specimens were then placed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 24 h. The specimens were then washed and dehydrated through ascending grades of ethyl alcohol (30%, 50%, 70%, and 100%) followed by air drying for 48 h. After dehydrating, the teeth specimens were fixed and sent for scanning electron microscope (SEM) examination.

The entire test surface of each specimen was scanned at first to get a general overview of the surface topography of each specimen. Then, scaled area was studied under SEM and different indexes were calculated. For each surface, randomly four photographs were taken at ×50 and ×100.

The specimens were examined for the amount of remaining calculus, surface roughness, and loss of tooth substance using the following indices:

Remaining calculus index (RCI) given by Meyer and Lie in 1977[10]

Loss of tooth substance index (LTSI) given by Meyer and Lie in 1977[10]

Roughness loss of tooth substance index (RLTSI) given by Lie and Leknes in 1985[11]

Presence or absence of smear layer.

The control group (untreated teeth) was not evaluated for roughness loss of tooth substance index. The data thus collected were analyzed and subjected to statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Scanning electron microscope interpretation

All of the samples after treating were prepared for SEM evaluation. A scanning electron microscope (JSM-6100 SEM, Jeol Company) was used for this part of the study. Standardized photomicrographs of the selected sites were obtained at magnification of ×50 and ×100 for each tooth specimen [Figures 1–3]. Results are depicted as number, percentage, and mean ± standard deviation along with the intergroup comparisons have been depicted in Tables 1–3. RCI, LTSI, and RLTSI mean score was calculated using descriptive analysis and one-way ANOVA test. Multiple intergroup comparisons were done using Tukey's honestly significant difference study. P = 0.05 or less was set for statistical significance.

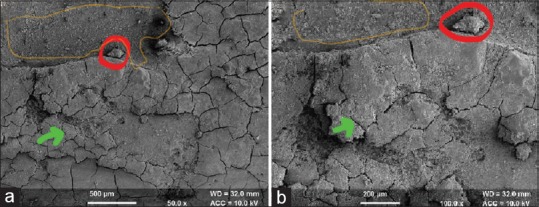

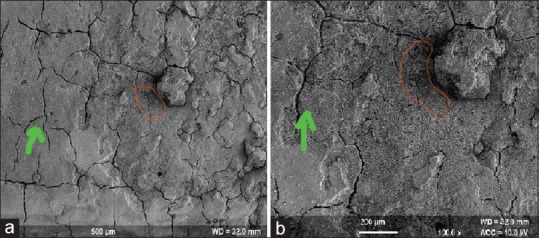

Figure 1.

Test Group I (unaided): Scanning electron microscope analysis (×50 and ×100). It shows the presence of smear layer, residual calculus in some parts, loss of tooth cementum in some areas, and roughness loss of tooth surface with visible cracks on the cementum surface. Residual calculus is marked with red color, loss of tooth substance with orange marking, and roughness loss with visible cracks as green marking. (a) test Group I at 50x magnification; (b) Test Group at 100x magnification; (Red colour) residual calculus on the root surface; (orange colour) loss of tooth substance; (green colour) roughness loss with visible cracks

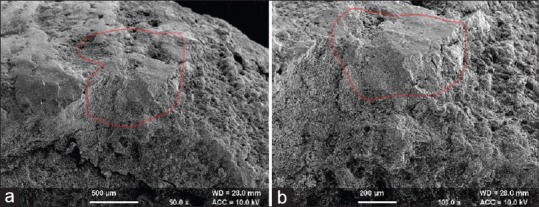

Figure 3.

Control Group III: Scanning electron microscope analysis of this group (×50 and ×100). It shows visible smear layer with cementum intact having slight cracks on the cementum surface. Residual embedded calculus is seen with no loss of tooth substance. It is marked with red color. (a) Control Group III at 50x magnification; (b) Control Group III at 100x magnification; (red colour) residual embedded calculus

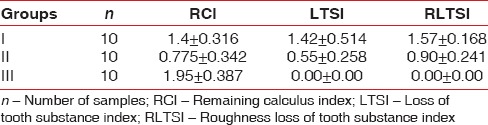

Table 1.

The mean score of parameters remaining calculus index, loss of tooth substance index, and roughness loss of tooth substance index

Table 3.

The intergroup comparison of all parameters

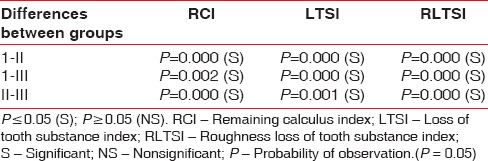

Figure 2.

Test Group II (aided): Scanning electron microscope analysis of this group (×50 and ×100). It shows no visible smear layer, no residual embedded calculus, and slight loss of tooth substance with some roughness loss of the tooth surface. Loss of tooth substance is marked orange color with cracks seen with green marking. (a) Test Group II at 50x magnification; (b) Test Group II at 100x magnification; (orange colour) loss of tooth substance; (green colour) cracks on the root surface

Remaining calculus index

Scanning electron microscopic analysis of the unaided (Group I) group showed remaining calculus on the treated root surface as patches of varying sizes scattered randomly whereas it was less visible in aided group (Group II). This difference (mean value test Group I – 1.4 ± 0.316 and test Group II – 0.77 ± 0.34) was found to be statistically significant. In control Group III (1.95 ± 0.387), a considerable amount of calculus was seen. The intergroup comparison is shown in Table 3.

Loss of tooth substance index

This index was measured in only test groups (Groups I and II). Scanning electron microscopic analysis of the unaided group (test Group I) showed distinct loss of tooth substance on most of the treated surface but without profound instrumentation marks in the dentine and it was also observed that cementum was absent in some areas. It was evident that area where cementum had been removed from the root surface, there was exposure of dentinal tubules. In aided group (test Group II), slight loss of tooth substance was confined to the localized areas and most of the cementum was unharmed. This difference (mean value Group I – 1.42 ± 0.514 and Group II – 0.55 ± 0.258) was found to be statistically significant. The intergroup comparison is shown in Table 3.

Roughness loss of tooth substance index

This index was measured in only test groups (Group I and Group II). Scanning electron microscopic analysis of the unaided group (Group I) showed definite localized corrugated areas with several areas demonstrating deep instrumentation marks extending into the dentine, while aided group (Group II) showed undulating or even root surface with slightly roughened areas confined to the cementum. This difference (mean value Group I – 1.57 ± 0.168 and Group II – 0.90 ± 0.241) was found to be statistically significant. The intergroup comparison is shown in Table 3.

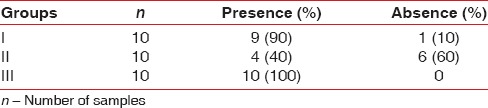

The presence or absence of smear layer in all the groups has been shown in Table 2. The results suggest that aided group (with magnification loupes) showed better results than the unaided group.

Table 2.

The percentage of presence and absence of smear layer

DISCUSSION

Since antiquity, the key objective of periodontal therapy is the elimination of supra- and sub-gingival plaque, calculus, and reduction of gingival inflammation.[12,13] From the accrued data over the years, researchers from the field of periodontology strive for clean root surface as the ultimate goal of the scaling and root planing during both the surgical and nonsurgical periodontal therapy.[4]

The removal of contaminated cementum from the root surface has long been a subject matter of debate. This cementum containing bacterial-derived endotoxins has an impending effect on gingival fibroblast attachment and proliferation. Nonetheless, various research studies till date have convincing evidence that pathological changes prevail only in the superficial layers of the contaminated tooth root surface, thus preserving the deeper layers of cementum.[8,14,15] It has also been observed that any changes in the root surface wall during root debridement could possibly affect the healing process.[8] Even though endotoxin has been described in literature to be attached loosely to the root surface, the possibility of comprehensive removal of all the endotoxins by root debridement is dubious.[16] However, the removal of these endotoxins with root planing from root surfaces remains the desired goal. In addition, it has been observed that after root planing, the topography of root surface does affect the consequent attachment of bacteria and consequently the outcome of treatment.[7]

Substantial instrumentation has been reported to cause increased surface roughness in supra- and sub-gingival areas that may lead to increased plaque retention.[17] Although increased surface roughness encourages more plaque retention, its importance for periodontal healing and regeneration has always been a matter of controversy. Studies have shown that fibroblasts do not attach and develop on diseased root surfaces nor do new attachment form on them, due to the presence of bacterial toxins.[1,16,18] In addition, it has been seen that curetted cementum exhibits newly synthesized fibrillar material and collagen fibrils produced by healthy, functional fibroblasts attached to the instrumented surface and evidently orients toward the surface that has been curetted.[19]

In the present study, microanalysis of root surfaces was performed using SEM to study the root surface characteristics under magnification to see whether scaling and root planing with magnification loupes is more effective or not. In test Group I in which scaling and root planing was done without the help of magnification loupes, it was observed that residual calculus was clearly discernible over the root surface either as blotches of different sizes confined randomly over majority of the treated root surface or present as persistent area covering most of the root surface. The presence of smear layer over the treated root surface suggested that mechanical periodontal therapy did not succeed in removing all bacteria. Areas with loss of tooth substance were evident where cementum had been removed, and there was exposure of dentin. Roughness due to the loss of tooth substance was evident with furrowed local areas in cementum or in the area where cementum may have been completely removed, with instrumentation marks in the dentin. Whereas in test Group II in which scaling and root planing was done with the help of magnification loupes, it was observed that root surface appeared smooth with fewer instrumentation marks and less amount of remaining calculus. As of the results driven from test Group II, it could be interpreted that scaling and root planing with the use of magnification loupes was more proficient in the removal of calculus with less significant loss of cementum and smoother root surface.

CONCLUSION

From the present study, it concludes that the use of magnification along with manual scaling appreciably increases the effectiveness of supra- and sub-gingival scaling and root planing as there is less loss of tooth surface and less roughness is on the tooth surface after the procedure. Furthermore, there is a need for the comprehensive understanding of the consequences that may occur on topography of root surface during instrumentation. Closed root planing using magnification loupes could produce the positive results clinically and histologically.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krishna R, De Stefano JA. Ultrasonic vs. hand instrumentation in periodontal therapy: Clinical outcomes. Periodontol 2000. 2016;71:113–27. doi: 10.1111/prd.12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dentino A, Lee S, Mailhot J, Hefti AF. Principles of periodontology. Periodontol 2000. 2013;61:16–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2011.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badersten A, Nilveus R, Egelberg J. Effect of nonsurgical periodontal therapy. II. Severely advanced periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1984;11:63–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1984.tb01309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adriaens PA, Adriaens LM. Effects of nonsurgical periodontal therapy on hard and soft tissues. Periodontol 2000. 2004;36:121–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2004.03676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graetz C, Plaumann A, Wittich R, Springer C, Kahl M, Dörfer CE, et al. Removal of simulated biofilm: An evaluation of the effect on root surfaces roughness after scaling. Clin Oral Investig. 2017;21:1021–8. doi: 10.1007/s00784-016-1861-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leknes KN, Lie T, Wikesjö UM, Böe OE, Selvig KA. Influence of tooth instrumentation roughness on gingival tissue reactions. J Periodontol. 1996;67:197–204. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.3.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosales-Leal JI, Flores AB, Contreras T, Bravo M, Cabrerizo-Vílchez MA, Mesa F, et al. Effect of root planing on surface topography: An in vivo randomized experimental trial. J Periodontal Res. 2015;50:205–10. doi: 10.1111/jre.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mishra MK, Prakash S. A comparative scanning electron microscopy study between hand instrument, ultrasonic scaling and erbium doped: Yttirum aluminum garnet laser on root surface: A morphological and thermal analysis. Contemp Clin Dent. 2013;4:198–205. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.114881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoerler SB, Branson BG, High AM, Mitchell TV. Effects of dental magnification lenses on indirect vision: A pilot study. J Dent Hyg. 2012;86:323–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer K, Lie T. Root surface roughness in response to periodontal instrumentation studied by combined use of microroughness measurements and scanning electron microscopy. J Clin Periodontol. 1977;4:77–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1977.tb01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lie T, Leknes KN. Evaluation of the effect on root surfaces of air turbine scalers and ultrasonic instrumentation. J Periodontol. 1985;56:522–31. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.9.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eick S, Bender P, Flury S, Lussi A, Sculean A. In vitro evaluation of surface roughness, adhesion of periodontal ligament fibroblasts, and Streptococcus gordonii following root instrumentation with Gracey curettes and subsequent polishing with diamond-coated curettes. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17:397–404. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0719-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohan R, Agrawal S, Gundappa M. Atomic force microscopy and scanning electron microscopy evaluation of efficacy of scaling and root planing using magnification: A randomized controlled clinical study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2013;4:286–94. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.118347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakib NM, Bissada NF, Simmelink JW, Goldstine SN. Endotoxin penetration into root cementum of periodontally healthy and diseased human teeth. J Periodontol. 1982;53:368–78. doi: 10.1902/jop.1982.53.6.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukazawa E, Nishimura K. Superficial cemental curettage: Its efficacy in promoting improved cellular attachment on human root surfaces previously damaged by periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1994;65:168–76. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deas DE, Moritz AJ, Sagun RS, Jr, Gruwell SF, Powell CA. Scaling and root planing vs. conservative surgery in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2016;71:128–39. doi: 10.1111/prd.12114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwarz F, Bieling K, Venghaus S, Sculean A, Jepsen S, Becker J, et al. Influence of fluorescence-controlled Er: YAG laser radiation, the vector system and hand instruments on periodontally diseased root surfaces in vivo. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:200–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babay N. Attachment of human gingival fibroblasts to periodontally involved root surface following scaling and/or etching procedures: A scanning electron microscopy study. Braz Dent J. 2001;12:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aspriello SD, Piemontese M, Levrini L, Sauro S. Ultramorphology of the root surface subsequent to hand-ultrasonic simultaneous instrumentation during non-surgical periodontal treatments: An in vitro study. J Appl Oral Sci. 2011;19:74–81. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572011000100015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]