Highlights

-

•

Morbidly obese patients do get cancer and require laparotomy for resection of the malignancy.

-

•

Sleeve gastrectomy can follow a successful oncologic intervention with minimal increase in morbidity and mortality.

-

•

Doing the oncologic procedure, HIPEC, and then sleeve gastrectomy helps prevent tumor seeding at the gastric staple line.

-

•

Patient satisfaction is high with a favorable prognosis expected from a simultaneous oncologic and bariatric intervention.

Keywords: Sleeve gastrectomy, Bariatric surgery, Oncologic surgery, Cytoreductive surgery, Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Morbidly obese patients may require a laparotomy to resect a malignancy. In some patients the cancer resection can be combined with the bariatric procedure to concomitantly treat both diseases.

Presentation of case

A morbidly obese patient with peritoneal metastases from an appendiceal mucinous neoplasm was evaluated and definitively treated with Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), at the same time the patient was treated for morbid obesity with sleeve gastrectomy and removal of a previous laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB).

Discussion

The clinical features and treatments of a cancer patient who underwent a combined surgical oncologic and bariatric procedure is presented. A second-look cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) preceded a sleeve gastrectomy. At the time of surgical exploration the prognosis from an oncologic perspective was acceptable. The near total gastric resection was performed without complications.

Conclusions

With short term follow-up, this patient’s outcome was favorable suggesting that surgical oncologic and bariatric procedures can be combined. Further, clinical investigations are indicated in this common clinical setting.

1. Introduction

Morbid obesity is an established risk factor for many types of malignancies [1]. Irrespective of the type of cancer, these patients may require surgical resection; with appropriate intervention the prognosis of these obese patients from an oncologic perspective may be favorable. However, allowing the morbid obesity to persist jeopardizes the long term well-being of the patient with regard to comorbid conditions, early mortality and quality of life. It may be possible, in carefully selected patients, to honor the best principles in oncologic surgery and in bariatric surgery at the same intervention [2,3]. One way to do this is to combine a potentially curative cancer resection with a sleeve gastrectomy. In this manuscript we present a patient managed at an academic institution who had a second-look surgery for perforated appendiceal cancer with a sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity. The selection factors for combined oncologic and bariatric procedures are discussed. To these authors’ knowledge, this is the first report of a sleeve gastrectomy performed concomitantly with a definitive oncologic procedure. This manuscript was constructed in compliance with consensus-based surgical case report guidelines (SCARE) [4]. This case report is registered as first-in-man study on the www.researchregistry.com website with UIN 4155.

2. Patient presentation

The patient is a 46 year old female who presented initially to an emergency room with an increasing right-sided abdominal pain, CT scan showed probable appendicitis and she underwent laparoscopic converted to open appendectomy and then right colectomy. Pathology revealed two lesions outside the appendix with epithelial cells within mucus. Appendix showed grade 1 adenocarcinoma pT4N0M1a. Appendix was 7 × 4 × 2 cm in size.

The patient was evaluated at our institution and thought to be a candidate for a second-look surgery plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC).

The patient has a past medical history significant for morbid obesity Body Mass Index (BMI) 52.2 kg/m2 with hypertension and non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Her family history was negative. Her past surgical history was significant for laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) 5 years before presentation and tubal ligation 18 years prior to presentation. She had initially lost 57 kg (approximately 60% excess weight loss) after LAGB, but her bariatric provider moved from the rural town and she didn’t have long term follow-up. Her band had been overly inflated to the point where she had developed maladaptive eating behaviors, would vomit when she tried to eat appropriate, protein dense foods and ultimately regained most of what she lost. On presentation to the office her weight was 151 kg. Current medications included lisinopril and glyburide. At the request of the surgical oncology team, the patient was evaluated by bariatric surgery team.

Upon evaluation her height was 172.7 cm, weight was 151 kg, with a BMI of 52.2 kg/m2. She met NIH criteria for surgical weight loss. There was additional concern that the presence of foreign body might pose a physical barrier to HIPEC and should be removed.

Because the patient had initially done well with a purely restrictive procedure, she requested conversion to a sleeve gastrectomy, rather than a malabsorptive procedure. Because of the theoretical increased risk of creating multiple staple lines and anastomoses in a patient with known malignancy undergoing a concomitant major surgical procedure, with the use of HIPEC, and given that she had already her ileocecal valve and right colon removed, we agreed that the sleeve gastrectomy was a reasonable approach. She received appropriate, albeit expedited, pre-operative nutritional and psychological evaluation and counseling prior to surgery.

The patient was taken to surgery for cytoreductive second-look surgery with HIPEC by an experienced peritoneal surface malignancy team (Fig. 1). The procedure included exploratory laparotomy, greater omentectomy, pelvic peritonectomy, hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and HIPEC [5]. A 1/3 dose reduction in intraperitoneal mitomycin C and doxorubicin was used.

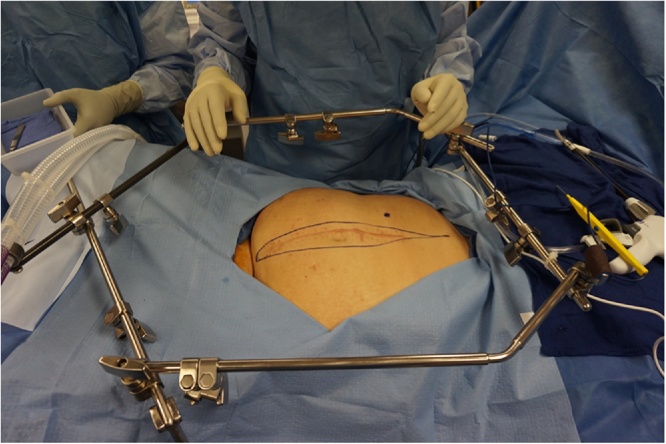

Fig. 1.

A self-retaining retractor is positioned prior to making the midline abdominal incision.

Before cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC, the bariatric surgery team performed the removal of the gastric band and port. After HIPEC was administered, sleeve gastrectomy was performed by an experienced bariatric surgery team without incident using SEAMGUARD (W. L. Gore & Associates, Inc., Medical Products Division Flagstaff, AZ) buttressed stapler (Ethicon Echelon Flex™ GST System) for the sleeve gastrectomy over 36 Fr. Maloney Tapered Esophageal Bougie (Teleflex Incorporated TFX, The Pilling® Brand). The combined procedure required 8 h (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

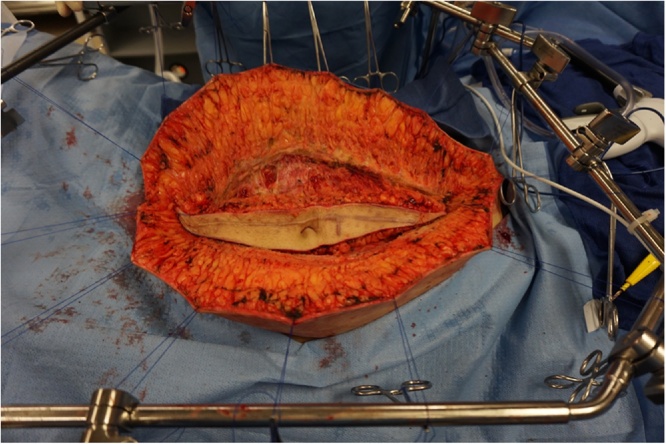

Fig. 2.

Through a long midline abdominal incision with resection of the old scar and umbilicus, the abdomen was opened. Initial exposure was maintained using skin traction sutures fixed to a self-retaining retractor.

Fig. 3.

The sleeve gastrectomy was performed over a 36 bougie in the absence of any contamination of the operative field.

The patient did well postoperatively and was discharged home 5 days after surgery. There were no postoperative adverse events and her weight loss is progressing, 3 months after surgery she had lost 27 kg. Weight is 124 kg from 151 kg preoperatively and BMI is 41.5 kg/m2.

from BMI 52.2 kg/m2 (Approximately 32% excess weight loss three months postoperatively). Follow-up CT to assess the status of the appendiceal malignancy will be performed every 6 months for 3 years and then yearly for a total of 5 years.

3. Discussion

3.1. Sequencing of a combined oncologic and bariatric intervention

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a surgical oncologic (second-look surgery with HIPEC) and bariatric (sleeve gastrectomy) procedures combined at a single intervention. Cancer cells seeding from the cancer resection to the operative site for the bariatric procedure is a major concern. Proper sequencing of the several steps of the intervention was necessary to achieve an optimal short-term and long-term favorable outcome. After the surgical exploration the failed gastric band and its port were removed. No cancer in the resection site of the circumferential inflatable device was seen. Following this the cytoreductive surgery was performed and all biopsies taken. After the oncologic procedures, HIPEC was used in an attempt to rid the abdomen and pelvis of any mucinous cancer cells. The HIPEC should be administered prior to the stapling of the stomach to minimize the possibility of tumor cell entrapment within the gastric staple line [6]. This prophylactic use of HIPEC to minimize tumor entrapment within a reconstruction should be a standardized part of a combined procedure in which peritoneal metastases could develop at a later time.

3.2. Prognosis of the oncologic surgical procedure

Adenocarcinoma of the appendix is rare. It accounts for 0.5% of all gastrointestinal cancers. It has three subtypes: Mucinous (55%), colonic (34%) and adenocarcinoid (11%) [7,8]. The mean age of diagnosis is in the fifth decade of life [8]. Our patient’s stage was pT4N0M1a which is stage IVA according to the 2010 edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)/Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging system. The prognosis of stage IV appendiceal adenocarcinoma is very poor with a 5-year survival rate of 22% [9]. These data were accumulated in the absence of cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC as a treatment alternative for patients with appendiceal neoplasms with peritoneal metastases.

Aggressive cytoreduction and HIPEC has been used for secondary peritoneal metastases in many centers throughout the world, although only one prospective and randomized trial has been completed [10]. Although most of these studies for aggressive cytoreduction and HIPEC are single center experiences, reported long-term outcomes are far superior to any reported for similar group of patients with peritoneal spread from appendiceal or colorectal adenocarcinoma treated in the absence of cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC. Recent updates of this institution’s experience with mucinous appendiceal neoplasm with peritoneal metastases included 967 patients treated with surgical cytoreduction and HIPEC over a 30-year period. Overall 10-year survival rate was 45% for patients with peritoneal mucinous carcinoma with complete cytoreduction [11]. This favorable prognosis from an oncologic perspective is suggested as a requirement for concomitant surgical oncologic and bariatric procedures.

3.3. Selection of the sleeve gastrectomy procedure

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) is unique procedure for weight loss in that there is no major anatomic alteration required for the placement of the device. In the past, it was performed frequently in bariatric surgery for weight loss. The number of LAGB procedures performed is declining concomitantly with a rise in the number of sleeve gastrectomy (SG) procedures [12]. The average weight loss after LAGB is well documented to be less than that of other bariatric procedures including sleeve gastrectomy (SG), Roux en-Y-Gastric Bypass (RYGB) and Duodenal Switch (DS) [13].

Conversion of LAGB to another weight loss procedure is indicated for patient who experienced satisfactory weight loss and improvement or resolution of their co-morbidities after LAGB and then experienced weight gain and/or recurrence of their co-morbidities [13]. It may also be indicated in those patients who initially have insufficient weight loss after band placement. Other indications include adverse outcomes such as slippage, dilation, migration, erosion, port/tube problems or band intolerance. Conversion procedures from LAGB to either SG or RYGB had been performed and published with variable outcomes. The excess weight loss is acceptable (31–60%) in conversion from LAGB to SG in short-term follow-up (6–36 months), the excess weight loss is also acceptable (23%–74%) in conversion from LAGB to RYGB [[14], [15], [16]]. However, the complication rate is higher in conversion procedures than primary corresponding ones. Coblijn et al [15] reported the leak rate was 5.6% in conversion from LAGB to SG with overall complication rate of 12.2%. Overall conversion from LAGB to SG is a rational plan.

3.4. Postoperative care

The combination of surgical oncologic and bariatric procedures in the same operative setting would cause an increased complexity of the postoperative care. In the patient presented no adverse events occurred and the patient was discharged home after five days. However, an experienced team of surgical oncologists and bariatric surgeons should carefully manage these patients postoperatively. Bariatric complications such as a leak from the sleeve gastrectomy could occur. Intraabdominal abscess from fluid loculations postoperatively as a result of the HIPEC could occur. Both the surgical oncologic and bariatric procedures carry a risk for venous thromboembolism and pneumonia. Dual management of the patient postoperatively by surgical oncologic and bariatric teams occurred in our patient and is mandatory.

4. Conclusions

Treatment planning in a morbidly obese patient with a new diagnosis of cancer requiring laparotomy presented a new challenge for surgical oncologists and a multidisciplinary team approach which may include a bariatric surgeon. Innovative preoperative evaluation, intraoperative collaboration and postoperative follow-up are essential to ensure appropriate and safe intervention. Clinical features of patients selected for this combined surgical oncologic and bariatric intervention may include: (1) Young age, (2) Excellent performance status, (3) Favorable prognosis, (4) Use of HIPEC, if peritoneal metastases could occur in the future.

Conflicts of interest

Timothy Shope, MD is a consultant for Ethicon. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding source

No sources of funding.

Ethical approval

MedStar Health Institutional Review Board has determined that a case report of less than three (3) patients does not meet the DHHS definition of research (45 CFR 46.102(d)(pre-2018)/45 CFR 46.102(l)(1/19/2017)) or the FDA definition of clinical investigation (21 CFR 46.102(c)) and therefore are not subject to IRB review requirements and do not require IRB approval.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Salaam Sadi, MD: study concept or design, data collection, data analysis or interpretation, writing the paper.

Paul H. Sugarbaker, MD: study concept or design, data collection, data analysis or interpretation, writing the paper.

Timothy Shope, MD: study concept or design, data collection, data analysis or interpretation, writing the paper.

Registration of research studies

Registered as first-in-man study on the www.researchregistry.com website with UIN 4155.

Guarantor

Paul H. Sugarbaker, MD.

Acknowledgement

None.

References

- 1.Arnold M., Pandeya N., Byrnes G. Global burden of cancer attributable to high body-mass index in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(1):36–46. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71123-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugarbaker P.H. Second-look surgery for colorectal cancer: revised selection factors and new treatment options for greater success. Int. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/915078. 8 pages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diamantis T., Apostolou K., Alexandrou A., Griniatsos J., Felekouras E., Tsigris C. Review of long term weight loss results after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2014;10(1):177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., for the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van der Speeten K., Stuart O.A., Sugarbaker P.H. Cancer chemotherapy for peritoneal metastases: pharmacology and treatment. In: Sugarbaker P.H., editor. Cytoreductive Surgery & Perioperative Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Surface Malignancy. Textbook and Video Atlas. 2nd edition. Cine-Med Publishing; Woodbury, CT: 2017. pp. 47–82. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sethna K.S., Sugarbaker P.H. New prospects for the control of peritoneal surface dissemination of gastric cancer using perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Cancer Ther. 2004;2:79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCusker M.E., Coté T.R., Clegg L.X., Sobin L.H. Primary malignant neoplasms of the appendix: a population-based study from the surveillance, epidemiology and end-results program, 1973–1998. Cancer. 2002;94(12):3307–3312. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruoff C., Hanna L., Zhi W., Shahzad G., Gotlieb V., Saif M.W. Cancers of the appendix: review of the literatures. ISRN Oncol. 2011;2011 doi: 10.5402/2011/728579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Data from the SEER 1973–2005 Public Use File diagnosed in years 1991–2000.

- 10.Verwaal V.J., van Ruth S., de Bree E. Randomized trial of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:3737. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugarbaker P.H. Pseudomyxoma peritonei and peritoneal metastases from appendiceal malignancy. In: Sugarbaker P.H., editor. Cytoreductive Surgery & Perioperative Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Surface Malignancy. Textbook and Video Atlas. 2nd edition. Cine-Med Publishing; Woodbury, CT: 2017. pp. 109–132. [Google Scholar]

- 12.https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers.

- 13.Berende C.A.S., De Zoete J.P., Smulders J.F., Nienhuijs S.W. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy feasible for bariatric revision surgery. Obes. Surg. 2012;22:330–334. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0501-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brethauer S.A., Kothari S., Sudan R., Williams B., English W.J., Brengman M. Systematic review on reoperative bariatric surgery American society for metabolic and bariatric surgery revision task force. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2014;10(5):952–972. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coblijn U.K., Verveld C.J., van Wagensveld B.A., Lagarde S.M. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as revisional procedure after adjustable gastric band—a systematic review. Obes. Surg. 2013;23(11):1899–1914. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khoursheed M., Al-Bader I., Mouzannar A., Al-Haddad A., Sayed A., Mohammad A., Fingerhut A. Sleeve gastrectomy or gastric bypass as revisional bariatric procedures: retrospective evaluation of outcomes. Surg. Endosc. Other Int. Tech. 2013;27(11):4277–4283. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]