Abstract

Objectives

The aim of the study was to compare the differences in learning outcomes for supervision training of healthcare professionals across four modes namely face-to-face, videoconference, online and blended modes. Furthermore, changes sustained at 3 months were examined.

Design/methods

A multimethods quasi-experimental longitudinal design was used. Data were collected at three points—before training, immediately after training and at 3 months post-training. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected through anonymous surveys and reflective summaries, respectively.

Results

Participants reported an increase in supervision knowledge and confidence immediately after training that was sustained at 3 months with all four modalities of training. Using analysis of variance, we found these changes were sustained at 3 months postcompletion (confidence p<0.01 and knowledge p<0.01). However, there was no statistically significant difference in outcomes between the four modes of training delivery (confidence, p=0.22 or knowledge, p=0.39). Reflective summary data highlighted the differences in terminology used by participant to describe their experiences across the different modes, the key role of the facilitator in training delivery and the merits and risks associated with online training.

Conclusions

When designed and delivered carefully, training can achieve comparable outcomes across all four modes of delivery. Regardless of the mode of delivery, the facilitator in training delivery is critical in ensuring positive outcomes.

Keywords: medical education and training, training delivery, health professional training

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first-known study to investigate four different training modes in postregistration healthcare professionals.

This study was conducted in an interprofessional setting across a number of professional groups.

Quantitative and qualitative data were collected at three different time points (before training, immediately after and at 3 months following training) to assess the impact of training modes on learning outcomes.

As the findings from this study were generated through self-report data, further research using more robust data is required.

Given the nature of the research design, the role of confounding factors (such as motivation to learn, drive to achieve learning outcomes) could not be eliminated.

Background

The returns of training, whether traditional or online, include improved performance and attitudes from employees necessary to achieve organisational growth.1 Technology-assisted learning is on the increase and is viewed as an excellent resource that offers flexibility to educators and students.2 Benefits of technology-assisted training have been clearly documented in the literature. These include increased flexibility, reduced travel costs and the ability to address the limited availability of training in rural, remote and underserved areas.1 3–6 Furthermore, technology-assisted learning removes any geographical or time constraints often associated with traditional face-to-face learning,2 thereby enhancing training access in rural and remote areas. However, the introduction of technology-assisted and online learning has given rise to some issues including quantity versus quality of educational practice.7 Therefore, the challenge for educationalists is to deliver an optimal learning experience that is effective and appropriate for participants’ learning needs.2

There is little research to accurately determine the benefits and pitfalls of online learning, particularly in comparison with the more traditional face-to-face learning. Researchers and educators are unsure how participants’ online experiences differ from their experiences in face-to-face learning environments. Gaining knowledge about processes and outcomes of online learning compared with face-to-face learning will enable stakeholders to make more informed decisions about future online course development and implementation.8 Studies comparing traditional face-to-face learning with technology-assisted and online learning are necessary to establish the value of non-traditional training modes in healthcare settings.2 Furthermore, there is a lack of studies that compare more than two modes of training.9 Additionally, there is a need for studies of practising healthcare professionals as opposed to preregistration student studies.10–13

Kirkpatrick’s four-level evaluation model is the most widely recognised model in evaluating training programmes.14 15 It is well accepted that there are gaps in training evaluation that target levels 3 and 4 of the Kirkpatrick’s model of evaluation, namely behaviour and results. This is because the evaluation is said to become more expensive and difficult to process with each successive level of this model.14–16 Therefore, it is common for studies to report participant reactions (level 1) or increase in knowledge post-training (level 2)17–19 Level 3 behaviour can be measured only when participants have had a period of time to implement what they have learnt in training. This makes it necessary to measure the impact of training after a period of time.20 Therefore to address the gaps outlined, this study investigated the differences in training outcomes (knowledge, confidence and behaviour) of healthcare professionals for four modes of delivery, namely face-to-face, videoconference, online and blended. Self-reported confidence and knowledge gained immediately after training and retained at 3 months were examined.

Methods

Study design

A multimethods quasi-experimental longitudinal design was used in this study. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected at three points, namely baseline (before training), postbaseline (after training) and at 3 months post-training completion.

Patient/public Involvement

Patients and/or public were not involved in the study.

Participants

This study was conducted across two Hospital and Health Services (HHS) in Queensland, namely the Darling Downs Hospital and Health Service (DDHHS) and Central Queensland Hospital and Health Service (CQHHS). Allied health, nursing, medical and dental professionals from these HHSs were invited to participate in the study. These two HHSs were chosen to achieve homogenous sampling21 as they were similar in terms of geography, with both HHSs having one bigger regional site and many rural/satellite sites.

Eligible and willing participants from DDHHS were recruited to the face-to-face and online modes of training, those consenting to participate from CQHHS were recruited to the videoconference and blended modes of training. This decision was made to accommodate the training organisation and delivery practicalities, as well as to maximise cost-efficiencies related to the facilitator travel (the geographical location of the Cunningham Centre, the training organisation, is within the DDHHS). Also, this sampling and recruitment strategy was chosen to achieve an adequate sample size (n=30 for each mode). Training opportunities involving the respective modes were advertised in DDHHS and CQHHS through targeted emails and marketing. Participants were provided with a participant information sheet that outlined information about the study.

Training

All the participants across the four modes of training were presented with the same information. All the training sessions were presented/co-ordinated by the first author to ensure consistency between the modes. This training is delivered to practising postregistration healthcare professionals to up-skill them in providing clinical supervision to other staff and students. Information on the contents of the Cunningham Centre22 supervisor training can be found in onlinesupplementary appendix A. The face-to-face training was a full-day workshop while the videoconference training was conducted over two half-a-day workshops. Online training was self-paced over 8 weeks and took up to 5 hours to complete. The blended mode of training involved the online component plus a 2-hour videoconference post-training completion. The videoconference session was used to facilitate discussion about the training content and answer participant questions. This difference in contact time between the modes reflects the nature of content delivery (ie, the face-to-face and videoconference modes included multiple group discussions of scenarios and group activities that took more time).

bmjopen-2017-021264supp001.pdf (80.1KB, pdf)

Measures

Survey

Quantitative data were collected using surveys at three points (baseline, postbaseline and at 3 months) administered through Typeform.23 The surveys captured information on participant demographics (baseline survey only), confidence and knowledge in supervision, satisfaction with training and changes to practice. Some questions in the survey instrument were adapted for use from the ‘Supervisor Self-Assessment tool’ originally developed by Hawkins and Shohet.24 The surveys had questions on the participant’s confidence and knowledge in providing supervision, satisfaction with training and access issues related to training. Questions related to confidence, knowledge and satisfaction were rated on a 10-point scale. The remaining questions had multiple choice responses with the option to enter additional comments. These questions were developed based on a literature review and on the Cunningham Centre’s standard workshop evaluation questionnaires. The survey was piloted with six people who had experience in workshop evaluations prior to its use in the study.

Reflective summary

Qualitative data were gathered using reflective summaries at two points (postbaseline and at 3 months). The reflective summary primarily captured participant views on the impact of training, mode of delivery used, enablers and barriers associated with that mode. The questions asked in the reflective summary are attached in online supplementary appendix B.

Data analysis

Quantitative data

Although the data were repeated measures in format, we found that participants had difficulty in consistently entering their unique identification code from survey to survey. This issue compounded the common issues of attrition routinely observed in longitudinal studies. Restricting our analyses to only data that could be matched across all survey points with the individual participants would have resulted in an unacceptable reduction in the analysed sample size (n=21). Given our analyses primarily aimed to compare groups between conditions (ie, delivery modes), we opted to admit all survey data, and forego identifying subjects over time, within conditions.

This approach yielded a 3×4 independent groups analysis of variance (ANOVA) design, rather than a mixed design, which might potentially yield an underpowered analysis. Given this analysis was not planned before the intervention, we undertook a post-hoc power analysis to determine the likelihood of detecting an effect size of 1 scale point (on a 10-point scale) which we nominated as the minimum meaningful effect size of interest. We employed the freely available G*Power application25 to calculate the probability of detecting this difference at post and follow-up, using average attained group sample sizes (N) and SD at these time points. As SDs were almost identical for the two dependent variables (DVs), knowledge and confidence, similar results were obtained for both variables. Our analysis had a typical power of 0.905 at post (SD=0.89, n=18) and a typical power of 0.71 at 3-month follow-up (SD=1.00, n=14).

Table 1 provides information about participants at baseline across delivery modes, for key demographic and work-status characteristics. There were no differences across modes for gender or work status. Significant differences were observed for age and location. Accordingly, we checked for a relationship between these covariates and the key outcome measures of confidence and knowledge at baseline. No significant relationships were found (absolute max r=0.02, p=0.79).

Table 1.

Group sample sizes at the three time points

| Online | Video | Face-to-face | Blended | |

| Baseline | 40 | 19 | 26 | 16 |

| Post | 17 | 19 | 23 | 12 |

| Three-month | 10 | 16 | 17 | 13 |

Qualitative data

Qualitative data from the reflective summaries were collated by an independent project support officer. The data were subsequently subject to inductive content analysis,26 independently by the first and the last authors. Content analysis is a research method for the subjective interpretation of the content of the text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns.26 Content analysis allows the researcher to measure the frequency of different categories and themes27 and hence has been chosen as the preferred method of analysis. The resulting themes were then compared by the two authors and consensus reached on the final themes for reporting. Various strategies were employed by the authors to improve the rigour in the qualitative data collection and analysis processes, namely completion of data analysis independently by the first and last authors, cross checking of themes and peer debriefing with the second author while completing the analysis and interpretation.28

Results

Quantitative

Of the 101 participants who provided data for the baseline survey, 91% (n=92) were female. Sixty-nine per cent (n=70) of participants were younger than 35 years, and 91% (n=92) were 45 years of age or less. Only 9% (n=9) were 56 years or older. Forty persons participated in online training, 19 in video training, 26 in face-to-face and 16 in blended mode of delivery. Table 2 shows the sample size in each group by time point. Further demographic information about the participants can be found in table 1. Seventy-one participants provided feedback at the initial post-training follow-up, and 56 participants provided further responses at a 3-month follow-up.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants at baseline

| N | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 9 | 8.9 |

| Female | 92 | 91.1 | |

| Age | <25 | 34 | 33.7 |

| 26–35 | 36 | 35.6 | |

| 46–55 | 22 | 21.8 | |

| 56–65 | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 65+ | 8 | 7.9 | |

| Training mode | Online | 40 | 39.6 |

| Video | 19 | 18.8 | |

| Face-to-face | 26 | 25.7 | |

| Blended | 16 | 15.8 | |

| Work location | Regional | 66 | 65.3 |

| Rural | 35 | 34.7 | |

| Work base | Hospital | 73 | 72.3 |

| Community | 13 | 12.9 | |

| Both | 15 | 14.9 | |

| Discipline | Allied health | 56 | 51.5 |

| Nursing | 36 | 35.6 | |

| Medicine | 5 | 4.9 | |

| Dentistry | 4 | 3.9 | |

| Other | 4 | 3.9 | |

| Postgraduate experience (years) |

<1 | 6 | 5.9 |

| 2–5 | 21 | 20.8 | |

| 6–10 | 31 | 30.7 | |

| 11–20 | 22 | 21.8 | |

| 21+ | 21 | 20.8 | |

| Work status | Full-time | 66 | 65.3 |

| Part-time | 35 | 34.7 |

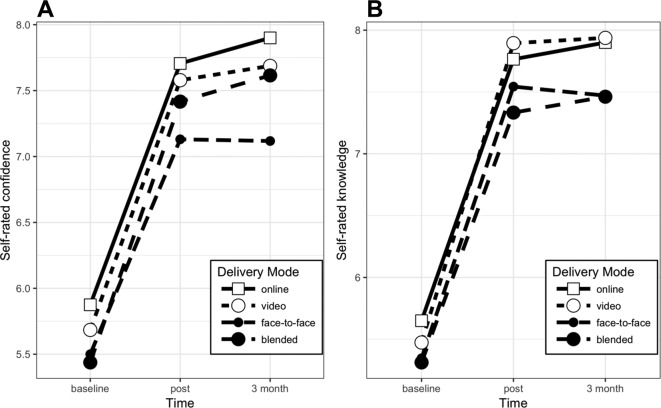

Participants were asked to rate their confidence and level of knowledge at each of the three time points. Figure 1 illustrates mean changes in confidence and knowledge by time and delivery mode. A 3 (time) x 4 (mode) ANOVA, implemented as general linear models, was conducted test for differences. Residuals were approximately normally distributed. There was a significant main effect for time in predicting both confidence, F(2)=39.4, p<0.01, and knowledge, F(2)=59.5, p<0.01. No significant main effect for mode was observed, in predicting either confidence, F(3) = 1.5, p=0.22, or knowledge, F(3)=0.99, p=0.39. Additionally, the inclusion of an interaction effect of time x mode did not significantly improve model fit for either confidence, F(6)=0.11, p=0.99, or knowledge, F(6) = 0.08, p=0.99. Table 3 provides model summaries of the general linear models: main-effects only, and with interactions, for each DV. As shown in figure 1, and the model summaries in table 3, self-rated confidence and knowledge increased significantly from baseline to postdelivery, and this increase was sustained at 3-month follow-up. In sum, all training methods resulted in sustained self-reported improvements, but there were no differences observed between training modes.

Figure 1.

Self-rated confidence (A) and knowledge (B) by delivery mode at baseline, postintervention and 3-month follow-up.

Table 3.

Regression beta coefficients and model summaries for general linear models predicting confidence and knowledge

| Dependent variable | ||||

| Confidence | Knowledge | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Time: post (vs baseline) | 1.815**(0.239) | 1.831**(0.447) | 2.196**(0.235) | 2.115**(0.439) |

| Time: 3 months (vs baseline) | 1.927**(0.259) | 2.025**(0.546) | 2.238**(0.255) | 2.250**(0.537) |

| Mode: video | −0.159(0.284) | −0.191(0.431) | −0.011(0.279) | −0.176(0.423) |

| Mode: face-to-face | −0.538*(0.268) | −0.375(0.389) | −0.314(0.263) | −0.304(0.382) |

| Mode: blended | −0.329(0.307) | −0.438(0.457) | −0.398(0.301) | −0.338(0.449) |

| Post x video | 0.064(0.672) | 0.306(0.660) | ||

| Three-month x video | −0.022(0.757) | 0.214(0.744) | ||

| Post x face-to-face | −0.200(0.629) | 0.083(0.618) | ||

| Three-month x face-to-face | −0.407(0.729) | −0.126(0.715) | ||

| Post x blended | 0.148(0.741) | −0.094(0.727) | ||

| Three-month x blended | 0.153(0.795) | −0.101(0.780) | ||

| Constant | 5.894**(0.205) | 5.875**(0.244) | 5.631**(0.201) | 5.650**(0.240) |

| Observations | 228 | 228 | 228 | 228 |

| r2 | 0.273 | 0.275 | 0.355 | 0.356 |

| Adjusted r2 | 0.256 | 0.238 | 0.340 | 0.323 |

| Residual SE | 1.527 (df=222) | 1.545 (df=216) | 1.499 (df=222) | 1.518 (df=216) |

| F statistic | 16.661** (df=5; 222) | 7.456** (df=11; 216) | 24.416** (df=5; 222) | 10.865** (df=11; 216) |

*P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Qualitative

Five themes were developed from the reflective summary data including language used by participants, most valuable part of training, facilitator being a key learning resource, merits and risks of online training and impact on practice.

Language used by participants

Participants in each of the four modes chose different terminology/words to describe their experiences. Face-to-face and videoconference participants commented extensively on the knowledge, skills, understanding and confidence gained. Online and blended participants used the words knowledge and understanding. Furthermore, while face-to-face participants commented extensively on finding the training enjoyable, this terminology was not used as much with the other modes.

When asked about the impact of training, one face-to-face participant said:

…Increased my confidence in providing supervision, particularly with regards to increasing my knowledge of formalised structure of supervision…Also increased my understanding in general and I think it will contribute to my ability to provide effective supervision in the workplace.

Most valuable part of training

Face-to-face and videoconference participants reported valuing the interaction with the facilitator and peers, group discussions, role plays and receiving immediate feedback from others in the room. Online participants reported videos of supervision scenarios as the most valuable part of training.

…the VC did assist my learning by still providing a person to ask questions and getting feedback straightaway…group activities were fabulous as I learn best by role playing, brainstorming in groups.….

A face-to-face participant said:

….face-to-face training assisted my learning greatly…being able to learn from peers in other disciplines was extremely valuable and a worthwhile learning opportunity in itself.

Facilitator is a key learning resource

Face-to-face and videoconference participants described the value of the facilitator in promoting learning. Online participants found the other learning resources like videos valuable. One videoconference participant said:

Facilitator presence (via VC) ensured attention to subject and allowed for meaningful activities, direction and clarification which improved learning…

A face-to-face participant commented thus:

…the trainer has taught us skills and improved our knowledge in a friendly and expert free environment.

An online participant said:

…video examples were useful. I enjoyed undertaking the quizzes also.

Merits and risks of online training

Some participants described the benefits of online training including reduced travel time and improved access. Participants who completed the blended mode also reported on advantages of that mode that were similar to the online mode. While commenting on this, one online participant said:

This mode was the only way I would be able to complete the training. I work rurally and getting time off to access training courses is difficult.

Another online participant said thus:

I liked having my own time to digest the information. I felt that had I been at face to face training this level of information may have been hard to retain.

A further online participant remarked:

I preferred the online as I could do it when I was free and as I liked to read and process it allowed me to do it at my own pace.

Echoing these perspectives, a participant who undertook training via the blended mode said:

I enjoyed this mode—it allowed me to process the info in my own time and take the time I needed to answer questions. I could re-read anything I didn’t understand. I like the voice over and written words—it helped me to process the information. The case studies were also helpful in making the information real and relevant.

However, some participants outlined the risks associated with online training such as tendency to skip over information, distractibility and competing priorities. One participant said thus:

Online was useful in not needing to travel. I was more prone to skipping through (supervision) models due to needing to get back to other work demands.

Another participant said:

…tried to sit down and complete the training during a normal working day, but found it difficult. So I completed it on a weekend shift when it was less chaotic.

Impact on practice

Many participants across all four training modes remarked about the impact the training has had on practice at the 3-month follow-up point. When asked about the changes that have been implemented following training, many participants commented on changes to the structure and content of supervision sessions, seeking more supervisee feedback and use of reflective practice models in supervision. One participant who completed the face-to-face training remarked thus:

I am undertaking different modes of learning within supervision such as chart reviews, joint treatment sessions.

Yet another face-to-face participant said:

I try to listen more to the point of view of others and understand why they may learn better with different approaches.

Responding to the same question, a videoconference participant said:

It has inspired me to conduct formal supervision and increased my knowledge and understanding of supervision and engaging in guided reflection to enhance practice…I really liked the Gibb’s and Rolfe’s models for reflection and have already begun using these for staff reflection.

Yet another videoconference participant said:

I have since the training started to provide supervision to other supervisees. So (I) firstly met with them to see if the relationship was a good fit and have progressed using some of the strategies to assist with their learning and have implemented the evaluation of supervision.

When asked about the changes implemented to practice, some online participants commented thus:

I have blocked off consistent supervision time to ensure adequate time and completion (of tasks) with the supervisee.

Use of reflective tools and models to help drive self-reflective learning with a student. I’ve been more confident in my role as a supervisor in the formative and supportive components.

More structured approach. Using SMART goals. Obtaining supervisee feedback.

Participants who completed the blended mode of training had similar responses when asked about the changes they have been able to implement to practice following supervision training. Some participant comments are provided below:

I asked for more feedback from supervisees about my supervision, to ensure we were achieving the goals initially set. I made sure to incorporate more time for reflection and feedback into sessions, and used the models discussed in training to do this.

Introduced different methods into supervision practice, used more tools around reflective practice, revisited goal setting.

Discussion

This is the first known study that investigated the differences in learning outcomes for four modes of training delivery for postregistration healthcare professionals. While the online and blended modes are becoming increasingly common, the evidence behind these remains limited, especially in the postregistration healthcare professional context. Previous research has highlighted the importance participants attribute to face-to-face training, with the other modes being perceived as the poor cousins.13 However, the findings of this study indicate that training delivery across face-to-face, videoconference, online and blended modes can be set up to achieve comparable outcomes. This is an important finding for many healthcare professionals in countries such as Australia that have a dispersed population. Given the increasing resource constraints,6 non-traditional forms of training delivery can improve access to training and achieve comparable outcomes to face-to-face training.

The study findings strengthen the findings of another study by Larson and Sung9 that found no significant differences in outcomes in the three modes of delivery, namely face-to-face, blended and online modes among students completing a management information systems course. However, similar to other studies in this area, this was again a study with students. The main strength of the study presented in this paper is the representation of postregistration practising healthcare professionals from a broad range of disciplines including allied health, nursing and medicine. Therefore, study findings are applicable to a broad range of professions. An additional strength of this study is the comparison of four training modes while most existing studies in the field have compared only two or three modes.9

This study has demonstrated that training for healthcare professionals can be set up to achieve comparable outcomes across different delivery modes. It is likely that participants across all modes reaped comparable benefits due to the initial investment made by the organisation while designing the different modes. It is also noteworthy that the authors took immense care to ensure that information was delivered consistently and learning facilitated in a similar manner to participants across all the modes. Therefore, resource investment into training development in the early phase appears to be integral to the achievement of learning outcomes in the later phases. This is supported by many models related to training and evaluation. For example, the input, process, output model proposed by Bushnell29 recognises the crucial role of the training input stage which relates to the trainer’s competence, training materials, facilities and equipment used.

This study is not without limitations. The use of Kirkpatrick’s model in training evaluation has been highly debated. However, it is argued that it is still a widely known and used model in training evaluations.15 The unique identification code for the survey could not be matched across all the three points, restricting the analyses that could have been performed at the individual level. However, this did not preclude the analyses required for addressing the study’s key comparisons. Although power was determined post-hoc to be reasonably sufficient post-training, our study had only a 70% chance of detecting a difference of 1 point at the 3-month follow-up. A larger subsequent study might detect more subtle differences in outcomes at follow-up. The other limitation was the resource-intensive nature of the study design. Co-ordinating and facilitating training for a broad range of healthcare professionals in two cohorts across two dispersed hospital and healthcare services, as well as collecting data at three points required extensive administrative support and trainer’s time. Any replication efforts for this study would need to factor sufficient resources to ensure successful implementation. Furthermore, this study collected self-reported data. Further studies are required that also evaluate outcomes from the workplace (eg, manager reports). It is possible that this study recruited participants that are much more motivated to learn and engage in continuing professional development which may have resulted in the positive outcomes (potential for self-selection bias). However, most practising healthcare professionals understand the importance of undertaking professional development to maintain their recency of practice, and hence, it is likely that the study recruited participants with different levels of motivation to learn. Future research could address these issues by recruiting a larger sample size which may provide a better representation of the population of interest. Lastly, this study used a multimethods, quasi-experimental longitudinal design in accordance with what was feasible within the context where this research was undertaken as well as time, resources and finances that were available to undertake this project. Future research using robust study designs, such as randomised controlled trials, are recommended as means of demonstrating causality, eliminating error and bias (such as selection and allocation bias) and controlling for confounders.

This study has provided valuable information for training providers, organisations and healthcare professionals regarding the use of different training delivery modes. For training providers, it highlights the value of ensuring consistency of information provided and the value in ensuring interactivity for non-traditional training modes. For organisations, it provides assurance that comparable training outcomes can be achieved for non-traditional modes of training as the face-to-face mode. For healthcare professionals, it provides information on the benefits and risks associated with different training modes that will better inform their choice of training mode.

Conclusion

This study compared four modes of training delivery, namely face-to-face, videoconference, online and blended. It recruited practising healthcare professionals from allied health, nursing, medicine and dentistry from two regional hospital and healthcare services in Queensland. All participants completed the Cunningham Centre Supervisor training in one of the four modes. The same information was presented by one trainer to all participants to ensure consistency between modes. Self-rated confidence and knowledge in the provision of supervision was measured before training, immediately after training and at 3 months post-training completion. Study findings have implications for practice, policy and research. Findings indicate that all four modes of training achieved a significant increase in confidence and knowledge that was also retained at 3 months post-training completion. The qualitative data collected highlight the important role of the training facilitator and the differences in participant experiences across the four training modes. This study provides key findings that can be used by healthcare professionals, training providers and healthcare organisations to inform policy and practice in this field. This study has also highlighted areas for future research including further studies that compare multiple training delivery modes for postregistration healthcare professionals to build the evidence, as well as studies of discipline-specific topics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms Carly Maurer and Ms Inga Alexander from the Central Queensland Hospital and Health Service who were the CQHHS site contacts for the study. The authors would like to thank Ms Loretta Cullinan and the administration staff from the Cunningham Centre Allied Health Education and Training team for assisting with the training and data collection processes.

Footnotes

Contributors: PM developed the study proposal, delivered/coordinated all the training sessions, led the data collection, analyses and publication development processes. LA conceived the idea for the study and contributed to the proposal development, data collection, analyses and publication development. SK and MB contributed to the proposal development, data collection, analyses and publication development. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a Toowoomba Hospital Foundation/Pure Land Learning College Grant (THF 2016 R2 01).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Darling Downs Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee for multi-sites (ref: HREC/16/QTDD/49).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data may be shared with interested parties by contacting the first author.

References

- 1. Bartley SJ, Golek JH. Evaluating the cost effectiveness of online and face-to-face instruction. Edu Tech Society 2004;7:167–75. [Google Scholar]

- 2. McColgan K, Rice C. An online training resource for clinical supervision. Nurs Stand 2012;26:35–9. 10.7748/cnp.v1.i9.pg45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Quinn A, Phillips A. Online Synchronous Technologies for Employee- and Client-Related Activities in Rural Communities. J Technol Hum Serv 2010;28:240–51. 10.1080/15228835.2011.565459 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rousmaniere T, Abbass A, Frederickson J. New developments in technology-assisted supervision and training: a practical overview. J Clin Psychol 2014;70:1082–93. 10.1002/jclp.22129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cameron M, Ray R, Sabesan S. Remote supervision of medical training via videoconference in northern Australia: a qualitative study of the perspectives of supervisors and trainees. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006444 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar S. Making the Most of What You Have: Challenges and Opportunities from Funding Restrictions on Health Practitioners Professional Development. J Allied Heal Sci Prac 2013;11. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Swenson PW, Online RPA. hybrid and blended coursework and the practice of technology-integrated teaching and learning within teacher education. Issues Teach Edu 2009;18:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnson SD, Aragon SR, Shaik N, et al. . Comparative analysis of learner satisfaction and learning outcomes in online and face-to-face learning environments. J Interact Learn Res 2000;11:29–49. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Larson DK, Sung C. Comparing student performance: online versus blended versus face-to-face. J Asyn Learn Net 2009;13. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Campbell M, Gibson W, Hall A, et al. . Online vs. face-to-face discussion in a Web-based research methods course for postgraduate nursing students: a quasi-experimental study. Int J Nurs Stud 2008;45:750–9. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carbonaro M, King S, Taylor E, et al. . Integration of e-learning technologies in an interprofessional health science course. Med Teach 2008;30:25–33. 10.1080/01421590701753450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Driscoll A, Jicha K, Hunt AN, et al. . Can online courses deliver in-class results? A comparison of student performance and satisfaction in an online versus a face-to-face introductory sociology course. Teach Socio 2012;40:312–31. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ke J, Nafukho FM, Tolson H. Professionals' perceptions of the effectiveness of online versus face-to-face Continuing Professional Education courses. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brewer EW. Evaluation Models for Evaluating Educational Programs." Assessing and Evaluating Adult Learning in Career and Technical Education. IGI Global 2011:106–26. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reio TG, Rocco TS, Smith DH, et al. . A Critique of Kirkpatrick’s Evaluation Model. New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resource Development 2017;29:35–53. 10.1002/nha3.20178 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hedges C, Wee B. Evaluating a professional development programme. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014;4:A76.1–A76. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000654.216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goodman MS, Si X, Stafford JD, et al. . Quantitative assessment of participant knowledge and evaluation of participant satisfaction in the CARES training program. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2012;6:361–8. 10.1353/cpr.2012.0051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Horsley T, Hyde C, Santesso N, et al. . Teaching critical appraisal skills in healthcare settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;11:CD001270 10.1002/14651858.CD001270.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shuval K, Shachak A, Linn S, et al. . The impact of an evidence-based medicine educational intervention on primary care physicians: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:327–31. 10.1007/s11606-006-0055-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. te Pas E, Wieringa-de Waard M, de Ruijter W, et al. . Learning results of GP trainers in a blended learning course on EBM: a cohort study. BMC Med Educ 2015;15:104 10.1186/s12909-015-0386-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Laerd dissertation. http://dissertation.laerd.com/purposive-sampling.php.

- 22. Cunningham Centre. 2017. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/cunninghamcentre/html/allied_health (Accessed on 19/12/2017).

- 23. Typeform. https://www.typeform.com/tour/?tf_source=google&tf_medium=paid&tf_campaign=AU%20|%20Brand%20-%20Exact&tf_content=Build%20Engaging%20Forms%20&%20Surveys&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIgIPq_byF2AIVhA4rCh0Z2A3_EAAYASAAEgKs3PD_BwE.

- 24. Hawkins P, Shohet R. Supervision in the Helping Professions. New York: MCGraw-Hill Companies, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, et al. . G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–91. 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 2013;15:398–405. 10.1111/nhs.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Patton MQ. Qual res eval methods. 3rd edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bushnell DS. Input, process, output: A model for evaluating training. Train Dev J 1990;44:41–3. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-021264supp001.pdf (80.1KB, pdf)