Abstract

Objective

Contamination of weaning food leads to diarrhoea in children under 5 years. Public health interventions to improve practices in low-income and middle-income countries are rare and often not evaluated using a randomised method. We describe an intervention implementation and provide baseline data for such a trial.

Design

Clustered randomised controlled trial.

Setting

Rural Gambia.

Participants

15 villages/clusters each with 20 randomly selected mothers with children aged 6–24 months per arm.

Intervention

To develop the public health intervention, we used: (A) formative research findings to determine theoretically based critical control point corrective measures and motivational drives for behaviour change of mothers; (B) lessons from a community-based weaning food hygiene programme in Nepal and a handwashing intervention programme in India; and (C) culturally based performing arts, competitions and environmental clues. Four intensive intervention days per village involved the existing health systems and village/cultural structures that enabled per-protocol implementation and engagement of whole villager communities.

Results

Baseline village and mother’s characteristics were balanced between the arms after randomisation. Most villages were farming villages accessing health centres within 10 miles, with no schools but numerous village committees and representing all Gambia’s three main ethnic groups. Mothers were mainly illiterate (60%) and farmers (92%); 24% and 10% of children under 5 years were reported to have diarrhoea and respiratory symptoms, respectively, in the last 7 days (dry season). Intervention process engaged whole village members and provided lessons for future implementation; culturally adapted performing arts were an important element.

Conclusion

This research has potential as a new low-cost and broadly available public health programme to reduce infection through weaning food. The theory-based intervention was widely consulted in the Gambia and with experts and was well accepted by the communities. Baseline analysis provides socioeconomic data and confirmation of Unicefs Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) data on the prevalence of diarrhoea and respiratory symptoms in the dry season in the poorest region of Gambia.

Trial registration number

PACTR201410000859336; Pre-results.

Keywords: cluster randomised controlled trial; diarrhoea; behaviour change; weaning-food, hygiene; community intervention; motivational drives

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Strongly theory-based community intervention.

Pragmatic public health intervention involving existing public health workforce, village and country leaders in rural Gambia (low cost and easy to replicate).

Use of traditional Gambian performers/performing arts in the intervention (attractive to villagers and target mothers).

For the trial, it is impossible to fully blind communities.

Villages selected from primary care villages in the poorest region of the Gambia may pose a generalisability constraint.

Background

It is estimated that 2 billion episodes of diarrhoea annually occur among children under 5 years resulting in over 1.2 million deaths globally.1 The highest prevalences are in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) clustered around those aged 6–24 months2: the weaning age. Contaminated weaning food3 is an obvious source of infection, but to date, the emphasis for research and interventions havs focused on water hygiene.

In general, handwashing with soap by mothers can reduce infant diarrhoea by 47%.4 A central element of safe food preparation is handwashing, but this is not the only component requiring improvement for weaning food hygiene.5 6 Two small individually randomised proof-of-concept efficacy trials with individual training and follow-up of mothers for a weaning-food hygiene intervention (in Mali6 and Bangladesh5) and a community intervention evaluated in a small before-and-after cluster study in Nepal7 explored potential alternatives. The former were too intensive to be scalable, while the latter needs to be evaluated in a larger trial and could be simplified further to become a model for a population-level intervention package.

Fundamentally, community-level interventions should be short, simple, culturally acceptable, low-cost and involve existing structures. In this article, we describe the intervention implementation and provide baseline data to evaluate such an intervention in the Gambia, West Africa. The Gambia has a high rate of childhood diarrhoea, but to our knowledge, there have been no recent studies or interventions on weaning food in the Gambia. Moreover, our formative research8 indicates that the practices and rates of contamination have not changed significantly since 1978.9 Significantly, we found that weaning food samples collected immediately after preparation before feeding to the child were significantly contaminated with faecal coliforms and that this contamination increased after more than 5 hours’ storage.8

The evaluation for our intervention was designed as a cluster randomised control trial (cRCT) as the intervention would be delivered at the village level. We describe here the intervention implementation phase of the complex public health community intervention and the baseline survey data for our cRCT. We draw lessons from our intervention implementation for future expansion. The primary objective of the main cRCT trial is to investigate the effects of a complex public health community intervention that sought to improve mothers’ weaning food hygiene practices. We further sought to investigate the effect of the intervention on the level of microbiological contamination in food and water prepared for the child’s consumption and to establish the prevalence of diarrhoea and respiratory symptoms, and diarrhoea admission, as reported by mothers.

Methods/design

Design

Villages were the unit of randomisation for this parallel cRCT. The 4-day community intervention was followed by a reminder visit after 5 months. Two cross-sectional samples were taken to measure baseline characteristics and outcomes: one before randomisation and the other 6 months postintervention roll-out. There were no changes to the protocol after commencement.

Setting and population

The cRCT was conducted in the Central River Region (CRR), one of the Gambia’s administrative regions. CRR is 48 000 km2 in area, organised into 11 districts with 659 villages, and has a population of 201 506 of which 41 334 (20%) are children under 5 years of age.10 CRR was selected for the intervention as it has the highest incidence diarrhoea in the Gambia, particularly in children aged 6–24 months (26.5% of children under 5 years had diarrhoea in the 2 weeks preceding the Unicef Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) in 2010 vs 17% nationally.11 The rates for acute respiratory infection (ARI) of children under 5 years were 14.2% in CRR compared with 6% nationally). CRR is rural, with low literacy, and is economically the poorest region in the Gambia. Villages in the region differ in their access to water supply and healthcare. A typical village has a head and a religious leader, but the size of settlements registered on the national population census (in 2013) ranges from as few as 27 to 1800 population per village, giving mean village size for CRR of 357 (SD±59).10 As with the other regions in the Gambia, Unicef and the Gambian Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MOH) have selected a number of villages (158 in CRR) to become primary healthcare (PHC) villages where they have trained (for 4 weeks) a village health worker (VHW) and a traditional birth attendant (TBA) to provide health promotion and basic health support to the villagers.12

Inclusion criteria for study villages for the intervention were PHC villages in CRR with a population of 200–450. It was felt that such villages, with lay health workers, would be best able to support the programme given the available resources. The 200–450 population criteria per village was decided on three grounds: the requirement for a minimum of 20 families with children aged 6–24 months, a population close to the mean village size in CRR (357) and the need to avoid villages that were too large given the size of the team implementing the intervention. Exclusions for the villages were those that were within 5 km of already selected villages.

Inclusion criteria for households within the villages for the baseline were mothers with children aged 6–24 months; exclusions were those expecting not to be resident in the village for the following 6 months. There were no other exclusions. Sample size calculation (online supplementary file 1) was based on data from formative research investigating behaviours and testing food and water samples for faecal coliforms.

bmjopen-2017-017573supp001.pdf (81.1KB, pdf)

Recruitment

The villages were randomly selected by an epidemiologist in the UK, aware of the biases potentially associated with a non-random village sampling, from a list of all villages in CRR after applying the selection criteria. We provided written and oral information and sought informed consent from the village heads for the villagers’ participation in the programme.

For the baseline, a list of all mothers with children aged between 6 months and 24 months living in the village at the time was obtained from the maternal child health register, and households were chosen randomly, based on the study criteria. Mothers gave written informed consent. In case of illiteracy, the information was read out (and a written copy left behind), and a thumb print was obtained in the presence of a family witness and the fieldworker.

Baseline measurement

During the initial recruitment visit (December 2014; dry season), after consent, we characterised all 30 villages and 201 randomly chosen mothers within them before randomisation and collected data about socioeconomic background of the families and diarrhoea and respiratory illnesses of the index child over the last 7 days.

Randomisation

Randomisation took place after all village heads provided consent and the baseline data collection had been completed. Randomisation was conducted by a statistician in the UK using a computerised random number generator. The villages were grouped and randomised within strata (north or south of the river and by quartiles of the village population) into 15 control and 15 intervention villages. Allocation concealment was not possible because the intervention team had to know which village would receive the intervention before it was implemented.

Blinding

While it was not possible to blind the implementers of the intervention programme or the families who received the intervention, the families exposed to the intervention were unaware of the comparative nature of the intervention with a control village.

Data analysis

This article presents the data for the baseline, which are analysed using descriptive summaries.

Control villages

After consent by the head of village and randomisation, the control villages received a 1-day visit by a public health officer (PHO) who, using a flip chart during a village gathering, talked about using water in household gardening. No further visits were made to the control villages.

Intervention

The intervention components and delivery package were theoretically based and informed by the local context from our formative research and by the lessons/tools from community interventions in handwashing studies in India13 and weaning food hygiene in Nepal.7 The latter employed the same theoretical models in similar study questions. The intervention comprised a community participation campaign delivered to all the villages and focused on mothers of weaning babies and those with children under 5 years in whole village. The intervention team visited each village on days 1, 2, 17 and 25 and was delivered between 16 February and 28 April 2015 (the dry season). A set of activities was conducted that involved mothers and other village members in village-wide events, neighbourhood meetings and home visits, with the wider involvement of the village authorities and volunteers.13 We included a fifth visit after 6 months as it was envisaged that were such a programme to be implemented at scale, then for the behaviour change to be sustained, villages would require a reminder visit before or early in the diarrhoea high-risk rainy season.14 Mothers and their families are busy at this time and hence more likely to forget weaning food hygiene behaviour. The programme’s daily schedule and tools and including their links with the motivational theory are summarised in tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Details of intervention activities and during visits to the intervention villages

| Event | Activity | Where | Time | Purpose | |

| Day 1 | Meeting the Alkalo (village head) |

|

Alkalo’s residence | 20 min |

|

| Announce to the villagers |

|

Within whole village | 2 hours |

|

|

| House-to-house visit with MaaSupervisors |

|

Residence of every household especially with young children | 3 hours |

|

|

| Record a short video |

|

Alkalo’s residence | 15 min |

|

|

| Afternoon village meeting |

|

Village ‘Bantaba’ (a central place where villagers meets – usually under a large tree) | 4 hours |

|

|

| Community volunteers training |

|

Village Bantaba | 2 hours |

|

|

| Day 2 | Meeting the Alkalo |

|

Alkalo’s residence | 10 min | As day 1 |

| Announce to the villagers | As day 1 | As day 1 | 2 hours | As day 1 | |

| House-to-house visit with MaaSupervisors |

|

Residence of each pledged mother | 3 hours |

|

|

| Ad hoc women or men meetings held separately in neighbourhoods |

|

Neighbourhoods | 30 min |

|

|

| Day 3 | Meeting Alkalo | As day 2 | As day 2 | 20 min | As day 2 |

| Announce to the villagers | As day 1 | As day 1 | 2 hours | As day 1 | |

| House-to-house visit with MaaSupervisors | As day 2. Additionally:

|

As day 2 | 3 hours | As day 2—additionally videoing to provide contingent reward. | |

| Afternoon village meeting | As day 1 and including the following:

|

As day 1 | 4 hours | As day 1 | |

| Day 4 | Meeting Alkalo | As day 2 | As day 2 | 20 min | As day 2 |

| Announce to village | As day 1 | As day 1 | 2 hours | As day 1 | |

| House-to-house visit with MaaSupervisors | As day 3 | As day 3 | 3 hours | As day 3 | |

| Afternoon village meeting | As Day 1 including the following:

|

As day 1 | 4 hours | As day 1 including below:

|

|

| Day 5 | Meeting Alkalo | As day 2 | As day 2 | 20 min | As day 2 |

| Announce to the villagers | As day 1 | As day 1 | 2 hours | As day 1 | |

| House-to-house visit with MaaSupervisors | As day 3 | As day 3 | 3 hours | As day 3 | |

| Afternoon village meeting | As day 4 but not including erection of the village board or certification | As day 4 | 4 hours | As day 4 |

The idea of a 4-day programme was adapted from the India SuperAmma study.13 However, the details of the activities during each day of the Team’s visit to the villages were adapted from Gautam et al’s Nepal study.13 Itself drawing on aspects from the SuperAmma India study (see footnote to table 3 for source of adapted tools).

PHO, public health officer; TBA, traditional birth attendant; TC, traditional communicator; VHW, village health worker.

Table 2.

Intervention tools and their application during the intervention

| Tool | Target population | Details | Purpose |

| Competitions for mothers and MaaSupervisors | |||

| Mother’s competitions* | Mother and children <5 years but specifically 6–24 months of age. | Three stages: (1) mothers who learnt the six behaviours and pledged to practice the behaviours (MaaFamboo); (2) mothers who demonstrated during a MaaSupervisor and a PHO visit a sustained practice of six behaviours (MaaSawaar); (3) mothers who did all the above and supported two other mothers to become a MaaFamboo (MaaChampion). |

To set graded tasks, provide general encouragement (contingent reward) for improved behaviour, prompt identification with a role model and by engaging community action to encourage a change of social norms. |

| MaaSupervisors competitions* | MaaSupervisors | Older respected woman who must encourage mothers (focus on a minimum of 10) of which 50% must achieve the MaaChampion status. | |

| Performing arts for all village members | |||

| Songs (at times combined with communal dancing)* | Mother of young children and all villagers attending meetings. |

Campaign song: information about the six behaviours and benefits of practices and specially explain the benefits of care and love in terms of a grateful child with a successful future. Pledged song: focused on nurture, disgust and purity to encourage mothers to pledge to carry out the practices. Welcome song: a cultural greeting song to welcome and honour the head of the village and those present, with elements of messages added. |

To engage communities particularly mothers and to make it easy for mothers to learn the behaviours form the songs. |

| Stories (portrayed in drama, animation and flip charts)* |

Story 1: story of MaaChampion heard from her grown up child who is now a successful doctor, proudly telling the story to her family. Story 2: story of Funtu about how villagers rejected her and how her child suffered, while meeting the MaaChampion and following her advice made her popular and a good mother. |

To stimulate the motivational drivers help mothers understand and remember the behaviours easily. To communicate the the behaviours in a graphically memorable and entertaining way. To prompt identification with the role model (MaaChampion) and consequences of not following the six behaviours. |

|

| Drama* | One drama: describing a day in the life of MaaChampion and Funtu. | ||

| Animations† |

Animation 1: choose soap.19 Shows a hand touching faeces and then eating with and without washing with soap first. Animation 2: SuperAmma.19 Shows a similar story to MaaChampion, but in an Indian village, with reference to handwashing with soap in general rather than references to food hygiene. |

||

| Environmental cues for mothers | |||

| Posters, danglers and medals* | Mother of young children in the competition. | All had six key intervention practices graphically written on them. The mother’s posters, dangler and medals were all displayed around the house and kitchen. | To provide non-monetary incentives (contingent reward) for mothers. To provide visual reminders of the six key messages in the kitchen and household. |

| Plastic sheet | A 1.5×1.5 locally available sheet of plastic. | To provide a visual reminders of the message about drying pots and utensils on a clean surface. To facilitate this practice at the start of the programme when villagers do not have easy access to plastic sheets. |

|

| Other tools for team members or villagers | |||

| Posters* | All village members. | Had six key intervention behaviours practices graphically written on them. | To remind and facilitate the mothers to perform the six key behaviours. |

| Flip charts* | Mother of young children and all villagers attending meetings. | The two stories and key behaviours were described in three different flip charts. | Visual aids for telling the stories in men and women’s discussion groups and to stimulate the motivational drivers. Mainly for MaaSupervisors to use during their home visits or community meetings to explain the behaviours. |

| T-shirts for the intervention team. | All village members. | Bearing project logo and title of MaaChampion. | To identify and formalise the intervention members. |

| Project banners | All village members. | A piece of polythene presenting six key messages and a photo of the MaaChampion on it, displayed temporarily in each village before the afternoon events. | To make villagers aware about intervention events and the six key behaviours. |

| Glo Germ* | Mother of young children and all villagers attending meetings. | Two adult volunteers: both rub the Glo Germ cream on their hands: one washes hands with soap and water, while the other with only water; then they put hands under UV lamp to show ‘glowing germs’ on the hands that did not use soap. | To use during the men and women’s group discussions to engender the motivational drive for disgust and consequences of not using soap. |

We used two theoretical frameworks in designing the intervention. First, Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP),15 16 which are conventionally used in the food processing industry to reduce microbiological contamination. The WHO/FAO Expert Committee on Food Safety has recommended the use of HACCP[s] in homes in LMICs to provide insight into food preparation hazards and remedial preventive measures.16 17 There is also evidence from efficacy and a small population trial that weaning food hygiene activities following the HACCP approach can help identify measures to improve weaning food safety.16 Table 3 summarises the corrective measures that were prioritised following our formative research.8

Table 3.

Critical control points and corrective measures (practices) and handwashing motivational drivers that were targeted by our weaning food hygiene intervention

| Critical control points | Corrective measures: behaviours the intervention aimed to improve |

| Before food preparation | 1. Handwashing with water and soap before food preparation. |

| 2. Washing of pots and utensils before food preparation and drying on a clean (and cleanable) surface. | |

| During cooking when hand becomes contaminated | 3. Handwashing with clean water and soap when contaminated during cooking. |

| Stored food storage before feeding to the child | 4. Reheating of premade food after storage before feeding. |

| Before feeding the child | 5. Handwashing with clean water and soap before feeding child (mother) or eating (child). |

| Water ready for drinking by the child | 6. Boiling and cooling of water ready for drinking by child. |

| Evo-Eco model motivational drivers for handwashing behaviour change | Definitions of motivational drivers |

| Nurture |

|

| Disgust |

|

| Affiliation |

|

| Status |

|

| Purity |

|

Second, we used an applied motivational behaviour change model18 that facilitated the application of identified corrective measures in a way that would add to mother’s knowledge and attitude and would motivate a change in mother’s behaviour. The model draws on psychology research that proposes ways of classifying various drivers of human behaviour. Our formative research found that nurture, disgust, affiliation, status and purity were the strongest motivational drives for our village mothers.8

As with the India and Nepal programmes,7 19 we focused on the use of performing arts (using culturally ingrained styles of drama and songs),20 competitions and environmental cues21 to deliver the HACCP corrective measures and motivational drives. Details of our community weaning food hygiene programme, which was designed by the research team at the University of Birmingham (which included a Gambian PHO from MOH), were widely consulted with expert health promotion agencies who were represented on a Local Scientific Advisory Committee in the Gambia (MOH, Unicef, WHO, University of the Gambia, National Nutrition Agency (NANA) and the MRC Gambia).

Subsequently, the material was translated into the three local languages (Mandinka, Wolof and Fula), field-tested and piloted iteratively by the intervention team in the CRR. This team, which also delivered the programme, comprised one literate male and one illiterate female traditional communicators (TCs) with health promotion experience, three PHOs from the local Regional Public Health Department (two with Higher National Diploma from the Gambian College School of Public Health with an additional Masters in Public Health) and an illiterate driver (for 24 days of the 60 days of the village visit, there were two PHOs in the team, while for the remainder days, there were three PHOs). TCs are performing artists who use traditional African drumming, singing and acting to communicate behaviours. The team were deliberately selected from the within existing structures in rural Gambia to demonstrate replicability and scaling. The team conducting the intervention during the 4-day village visits was assisted by a female volunteer (usually a TBA) from each village who received 2 weeks training assisted the work programme during, and in-between, the team visits. The TBAs were encouraged to find one or more assistant volunteers by day 1 of the team’s visit (3 visits in smaller villages ended with no assistants, 11 had one assistant and 1 had three assistants). The assistants were called ‘MaaSupervisors’ and visited the families between team visits to recruit more mothers of young children, reinforce the target practices and hence help ingrain the practices with the cultural norms of the wider community.

The intervention focused on a central role model character, the ‘MaaChampion’, a mother who practised the key behaviours used in the messages (table 3) and encouraged other mothers to do the same. Village mothers could achieve ‘MaaChampion’ status if they successfully demonstrate the practices and knowledge and encouraged two other mothers to do so. ‘Funtu’ (a derogatory noun for a discarded useless thing) was another character: a mother who failed to practise any of the target behaviours and reaped the consequences with her family and other villagers. These two characters were described using story drama and songs in the context of an average village. Together they demonstrated all the key behaviours and motivational drives and engendered a wish for behaviour change in village mothers as they identified with the characters’ lifestyles and behaviours.

Other components such as competitions (for mothers of children younger than 5 years), environmental cues (for mothers engaged in the competitions) and demonstrations had an important role in embedding behaviour change. The programme’s daily schedule and tools, including their link with the motivational theory, are summarised in tables 1 and 2.

Overall, the aim was to apply theory and apply successful elements of two previous studies7 19 while ensuring the intervention was as simple and cost-effective as possible. It also needed to be understandable and replicable by existing local health system/staff in the Gambia.

Implementation was staggered over 2 months. During implementation of the intervention, there were no diversions from the protocol. The intervention team logged significant events, comments and the overall participation of villagers/mothers in the programme to enable full evaluation of the intervention implementation. At the end of the intervention implementation, the intervention team were interviewed in a focus group discussion to explore the experience of the team during village visits and implementation and identify successful elements and learning points. These will be reported in a qualitative publication.

Patient and public involvement

Patients

The details of the intervention were developed in consultation with mothers and villagers during an extensive piloting phase. There were no particular patient advisors. The results will be communicated after the follow-up is complete through the PHOs who visit the villages. There was no other involvement of patients.

Results

Recruitment and baseline characteristics

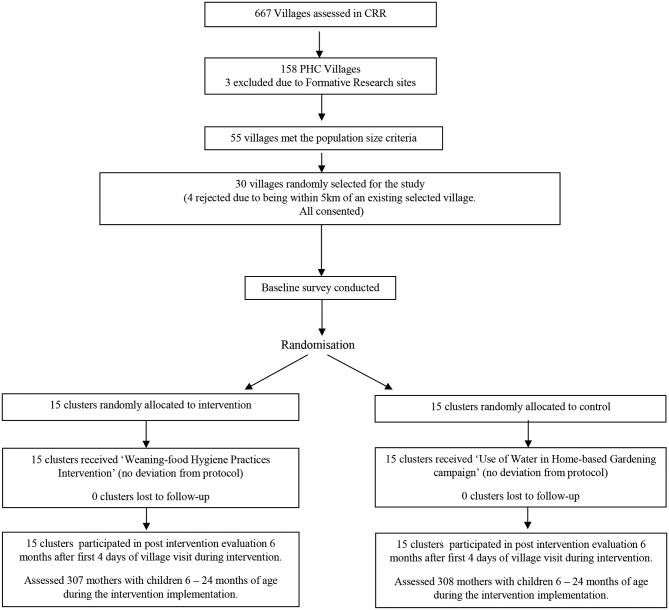

The trial flow chart (figure 1) outlines how 15 clusters were recruited per arm with a total of 300 mothers in the intervention and 300 in control villages at baseline. No village or family refused to participate. The median village size was 351 (IQR 297–400) in intervention and 354 (IQR 282–406) in control villages. The background characteristics of villages and baseline families were well balanced between the arms (tables 4 and 5). The majority of villages had no school and no health facility within 5 km; the main source of income for all villages was farming with only the three major Gambian ethnic groups represented. All villages had development groups and most had women’s groups or water subgroups indicating some village level organisation.

Figure 1.

The trial flow chart. CRR, Central River Region; PHC, primary healthcare.

Table 4.

Thirty village/cluster baseline characteristics by study arms (n=30)

| Variables | Control n=15 | Intervention n=15 |

| Village population, n | 5088 | 5219 |

| Village population, median (IQR) | 255 [297-400] | 306 [244 – 352] |

| Households per village, median (IQR) | 40 (30–60) | 33 (26–49) |

| Children aged <5 years, median (IQR) | 86 (71–111) | 86 (77–99) |

| Children aged 6–24 months, median (IQR) | 39 (34–57) | 43 (33–55) |

| Major ethnic group in village, n (%) | ||

| Mandingo | 3 (20) | 5 (33.3) |

| Wolof | 5 (33) | 5 (33.3) |

| Fula | 7 (47) | 5 (33.3) |

| Main income of villages, n (%) | ||

| Farming | 12 (80) | 13 (87) |

| Farming and business | 3 (20) | 2 (13) |

| Distance to nearest health facility* | ||

| <5 km | 6 (40) | 7 (56) |

| ≥5 to ≤ 10 km | 5 (33) | 4 (27) |

| >10 km | 4 (27) | 4 (27) |

| Availability of school in the village, n (%) | ||

| No school | 8 (53) | 10 (67) |

| Primary | 5 (33) | 5 (33) |

| Primary and middle | 2 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Availability of village/community groups, n (%) | ||

| Village development committee | 15 (100) | 15 (100) |

| Water subcommittee | 11 (73) | 7 (47) |

| Women’s group | 13 (87) | 15 (100) |

| Location of village | ||

| North of river | 7 | 7 |

| South of river | 8 | 8 |

| Quartile of population size of villages | ||

| 1 | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | 4 | 4 |

| 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 |

*This is the actual travel distance by mothers on food or transport and not the scaled map distance.

Table 5.

Characteristics of mothers in the evaluation survey by intervention allocation

| Variables | Control n=300 | Intervention n=300 |

| Number of children alive for index mother (IQR) | 3 (2–6) | 4 (3–6) |

| Age group of mother | ||

| <20 years | 31 (10) | 27 (9) |

| 20–30 years | 171 (57) | 186 (62) |

| >30 years | 97 (32) | 88 (29) |

| Education level of mother | ||

| None/illiterate | 186 (62) | 177 (59) |

| Other (Islamic, home and others) | 56 (19) | 51 (17) |

| Primary | 30 (10) | 39 (13) |

| Secondary or higher* | 28 (9) | 33 (11) |

| Ethnicity of mother | ||

| Mandingo | 46 (15) | 78 (26) |

| Wolof | 120 (41) | 96 (32) |

| Fula | 127 (43) | 118 (39) |

| Other | 3 (2) | 8 (3) |

| Occupation of mother† | ||

| Farmer | 280 (93) | 275 (92) |

| Other‡ | 20 (7) | 25 (8) |

| Ethnicity of husband | ||

| Mandingo | 47 (16) | 82 (28) |

| Wolof | 119 (40) | 96 (33) |

| Fula | 126 (43) | 115 (39) |

| Other | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Structure of house | ||

| Cement wall, corrugated roof |

32 (11) | 43 (15) |

| Mud wall, corrugated roof |

124 (43) | 121 (41) |

| Mud wall, thatched roof | 134 (46) | 129 (44) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Belongings | ||

| Land | 282 (95) | 280 (94) |

| Cattle | 173 (58) | 178 (59) |

| Goat | 216 (73) | 216 (72) |

| Mobile | 253 (85) | 269 (90) |

| Radio | 191 (64) | 203 (68) |

| Tap | 4 (1) | 9 (3) |

| Fridge | 3 (1) | 8 (3) |

| Source of water | ||

| Covered well or tap | 119 (40) | 141 (48) |

| Open well or other open water sources | 181 (60) | 152 (52) |

| Sex of index child male | 156 (52) | 151 (50) |

| Mean age (months) of child (SD) | 18 (7.9) | 19 (7.6) |

| Reported diarrhoea by mother in past 7 days§ | 60 (20) | 82 (28) |

| Reported ARI by mother in past 7 days¶ | 30 (10) | 30 (10) |

Values for the individual variables are numbers (%) unless otherwise stated.

*Arabic/Islamic, senior secondary or college.

†All mothers were housewives but had additional regular other work.

‡Trading, animal husbandry or civil servant.

§Defined as ≥3 watery stools in previous 24 hours.

¶Defined as cough with difficulty breathing.

ARI, acute respiratory infection.

The majority of the mothers were farmers (555, 92%) and illiterate (363, 60%). The structure of the houses and belongings provided a good indication of economic status and indicated that nearly half could be categorised as poor by rural Gambian standards with no cattle and houses with thatched roof and mud walls.

Intervention development and implementation

Stories, songs, posters and animations from previous relevant programmes in India and Nepal were transferable from Asia to our African setting, and the tools were easy to adapt within 6 weeks (including staff training, refining of the material, field testing and piloting). Material production (banners, posters, flip charts and so on) took a further 4 weeks. Animations from South Asia (available on public domain) were used unchanged and seemed to fully engage our target audience (live translation of spoken words was provided during the showing).

For replicating the programme in other settings, particular lessons were learnt for low-cost adaptation and replication of the material that are important for scaling such programmes. First, it was initially intended that the story booklets/flip charts would have graphics drawn by a professional artist (as per Nepal study), but the team found that printed photographs of consented local women/actors performing the stories in a local home was more effective for the story flip charts and other printed material. They could be done by the team members themselves rather than professionally produced, thus lowering the cost.

Second, unlike the Nepal programme where each village visit detailed one theme/behaviour, all behaviours/practices were discussed in all visits. This simplified the intervention and meant that the same tools, stories and songs could be used more than once during village visits. Moreover, as there were only four core visits and one reminder visit, we found that villagers continued to be interested in the material: repetition brought familiarity that helped participants to understand the behaviours in more depth and to relate the stories and songs to their lives. From the 571 mothers of children aged 6–24 months in the 15 intervention villages, during the four visits, there were 392 (69%) MaaFamboos (pledged) to 291 (51%) MaaChampions. All villages reached the status of ‘Weaning-food Hygiene Village’ with a third of mothers of children under 5 years as MaaChampions. All levels of the community, including men, women of all ages and children were involved in the programme as they attended meetings, encouraged each other to participate and sang the songs.

Discussion

We summarise an intervention [implementation] and provide baseline data of the first African randomised trial of a community-level weaning food hygiene programme. The baseline characteristics revealed satisfactory randomisation with villages and families that were representative of the Gambia’s CRR.11 Reported diarrhoea and ARI rates in our dry season (best conditions for villagers) agreed with a 2010 MICS survey for CRR (26.5% and 14.2%, respectively).11

The intervention strengths include a strong theoretical base and application of appropriate, replicable and transferable tools from two Asian programmes (in Nepal and India). The communities welcomed the use of culturally embedded performing arts, while the involvement of regional PHOs, rather than research staff, provided a pragmatic and potentially scalable intervention.

A possible limitation affecting the generalisability of our intervention implementation is that non-PHC villages were not sampled. However, as the MaaSupervisors were from any background and we trained them for 2 weeks, the intervention did not rely on the training of TBAs and VHWs. Thus, we anticipate that this intervention could have been implemented in non-PHC villages. A further limitation is that a formal qualitative evaluation process was not conducted, although documented observations from the programme implementation and a focus group with the project team shortly after the implementation will provide evidence of success elements. The involvement of policy makers, public health managers and funders from the start, as well as local implementing agencies (as part of the Local Scientific Advisory Committee) helped avoid potential bureaucratic or other threats to the programme. As the delivery method is low-cost, replicable and uses existing systems (PHOs, village organisations and TCs), the programme could be scaled up even with relatively limited resources. If combined with related programmes on child nutrition or Community-led Total Sanitation ran by Unicef, NANA or MOH, our intervention, if proven effective, could further strengthen existing health systems with the training and use of non-specialised staff in rural settings.

Performing arts, although used in health promotion campaigns, are rarely evaluated as instruments in themselves for community behaviour change. Although formal evaluation of their work was beyond our resources, it was found that the wider community engagement (men and women; young and old) was primarily due to the initial attraction provided by the TCs. During team visits, they engendered a joyous atmosphere, and their songs and stories became ingrained in daily village life with their repetition by children and villagers learnt and repeated them. Qualitative data from team members (Manjang et al, in preparation), who were experienced PHOs delivering government or Unicef health promotion programmes, revealed that drama, animation, songs, stories and handwashing demonstrations using Glo Germ22 were much more effective than the traditional communication of the behaviours with talks and flip charts/posters that the team members had used in previous projects. The villagers seemed to adopt the stories and songs, calling/singing them out loud as the team walked around the village and between visits. On the whole, the villagers welcomed the team and all components of the programme, including the competitions that increased peer support and that encouraged mothers of young children to achieve MaaChampion status.

A controversial issue relating to the use of performing arts is the need to adapt the tools to different cultural settings. Significantly, for expansion of this, or similar hygiene programmes, we found the tools from Asia (India and Nepal) were easy to adapt to the style of communication used by African TCs and performing artists. There is a dearth of literature describing formal evaluations of the use of such TCs in song and drama during campaigns, and we hope to contribute to this after reporting the trial data.

Conclusion

We describe a theoretically based community intervention in a low socioeconomic population region of the Gambia with high child morbidity. We found that weaning food hygiene intervention programmes based on HACCP and motivational theory, and using culturally engendered performing arts, may be transferable across LMICs. At the implementation stage, the study was successful in the active involvement of policy makers and public health service providers (PHOs) and traditional performing artists and village authorities. This engagement was successful in developing and implementing tools, leading to a low-cost intervention that was easy to deliver within existing public health structures and was well received by villagers in the lowest resourced region of the Gambia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the support of the members of the intervention team, all other study staff, the agencies participating in the Local Scientific Advisory Committee, the Village Heads and families. We are particularly thankful for the support of the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare and the Regional Directorate for CRR, National Nutrition Agency and Unicef-Gambia. We particularly would like to thank MRC Gambia for their support in Banjul and CRR. We are grateful for information from Dr Om P Gautam and Dr V Curtis about their respective studies in the Nepal and India.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to design of the study/study protocol and helped with drafting the manuscript (JE contributed to draft of protocol and early versions of manuscript before his murder). The following specific contributions apply: BM: trial manager, contributed to design and development of the intervention and evaluation, implementation of the study in the field, data collection and data analysis, Co-PI; KH: senior trial statistician and RCT design and Co-I; JTM: junior trial statistician contributing to analysis plan and analysis; SC and JE: WASH experts contributed to design of the intervention and evaluation in the RCT; CB: water scientist contributed to the design of study in general pertaining to safe waters and testing; JS and AJ: both public health officers, contributed to the development of the intervention and its implementation and study design; SM-H: trial director, contributed to design and development of the intervention, evaluation and the trial as a whole, implementation of the intervention and completion of the data collection and Co-PI.

Funding: This work was supported by Islamic Development Bank PhD scholarship for Buba Manjang, the UK Department for International Development through the SHARE Consortium led by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and Unicef Gambia Country Office.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study had full ethical approval from Gambia Government/MRC Joint Ethics committee (SCC 1385v2) and the University of Birmingham (ERN_14-0574). A written informed consent form was obtained from caregivers of children aged 6–24 months. All the information collected was kept strictly confidential.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: This paper only documents the baseline data for a cluster randomised controlled trial. The remaining analysis is still not completed and will be done by our research team. Once this is complete, the database is available for other researchers from the corresponding author after 5 years to allow for all required use by the primary research team.

References

- 1. Lamberti LM, Fischer Walker CL, Noiman A, et al. . Breastfeeding and the risk for diarrhea morbidity and mortality. BMC Public Health 2011;11:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walker CL, Rudan I, Liu L, et al. . Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet 2013;381:1405–16. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60222-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fischer Walker CL, Perin J, Aryee MJ, et al. . Diarrhea incidence in low- and middle-income countries in 1990 and 2010: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2012;12:220 10.1186/1471-2458-12-220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Curtis V, Cairncross S. Effect of washing hands with soap on diarrhoea risk in the community: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 2003;3:275–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Islam MS, Mahmud ZH, Gope PS, et al. . Hygiene intervention reduces contamination of weaning food in Bangladesh. Tropical Medicine & International Health 2013;18:250–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Touré O, Coulibaly S, Arby A, et al. . Piloting an intervention to improve microbiological food safety in Peri-Urban Mali. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2013;216:138–45. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gautam O. Food hygiene intervention to improve food hygiene behaviours, and reduce food contamination in Nepal: an exploratory trial [Doctoral]: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Manjang B. Investitgating Effectiveness of Behavioural Change Intervention in Improving Mothers Weaning Food Handling Practices: Design of a Cluster Randomized Controlled. Trial in Rural Gambia: University of Birmingham, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rowland MG, Barrell RA, Whitehead RG. Bacterial contamination in traditional Gambian weaning foods. Lancet 1978;1:136–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. GBOS. Po pulation and Ho using Census Preliminary R esults. Gbos: Gbos 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11. GMB-GBOS-MICS4-2011-v01. The Gambia - Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey. Ministry of Finance: Fourth Round. Gambia Bureau of Statistics, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Health MO, amp; WS, Banjul t G, et al. . In: HEALTH MO, &, WELFARE S, BANJUL T, GAMBIA, editors. Banjul, The Gambia. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eldridge SM, Ashby D, Kerry S. Sample size for cluster randomized trials: effect of coefficient of variation of cluster size and analysis method. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:1292–300. 10.1093/ije/dyl129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brewster DR, Greenwood BM. Seasonal variation of paediatric diseases in The Gambia, west Africa. Ann Trop Paediatr 1993;13:133–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bryan F. Hazard analysis critical control point evaluations, a guide to identifying hazards and assessing risks associated with food preparation and storage: World Health Organisation, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hulebak KL, Schlosser W. Hazard analysis and critical control point (HACCP) history and conceptual overview. Risk Anal 2002;22:547–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. WHO. Application of the hazard analysis critical control point (HACCP) system for the improvement of food safety: WHO, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aunger R, Curtis V. The Evo–Eco Approach to Behaviour Change. Applied Evolutionary Anthropology: Springer, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Biran A, Schmidt WP, Varadharajan KS, et al. . Effect of a behaviour-change intervention on handwashing with soap in India (SuperAmma): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health 2014;2:e145–e54. 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70160-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Daykin N, Orme J, Evans D, et al. . The impact of participation in performing arts on adolescent health and behaviour: a systematic review of the literature. J Health Psychol 2008;13:251–64. 10.1177/1359105307086699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol 2008;27:379–88. 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tools HT. Home Training tools. wwwhomesciencetoolscom 2007.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-017573supp001.pdf (81.1KB, pdf)