Abstract

Tryptophan lyase (NosL) catalyzes the formation of 3-methylindole-2-carboxylic acid and 3-methylindole from L-tryptophan. In this paper, we provide evidence supporting a formate radical intermediate and demonstrate that cyanide is a byproduct of the NosL-catalyzed reaction with L-tryptophan. These experiments require a major revision of the NosL mechanism and uncover an unanticipated connection between NosL and HydG, the radical SAM enzyme that forms cyanide and carbon monoxide from tyrosine during the biosynthesis of the metallo-cluster of the [Fe–Fe] hydrogenase.

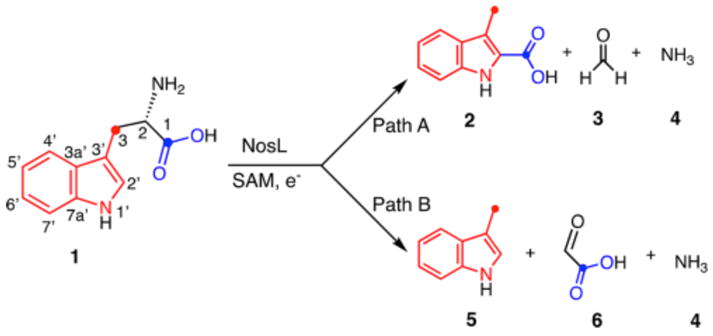

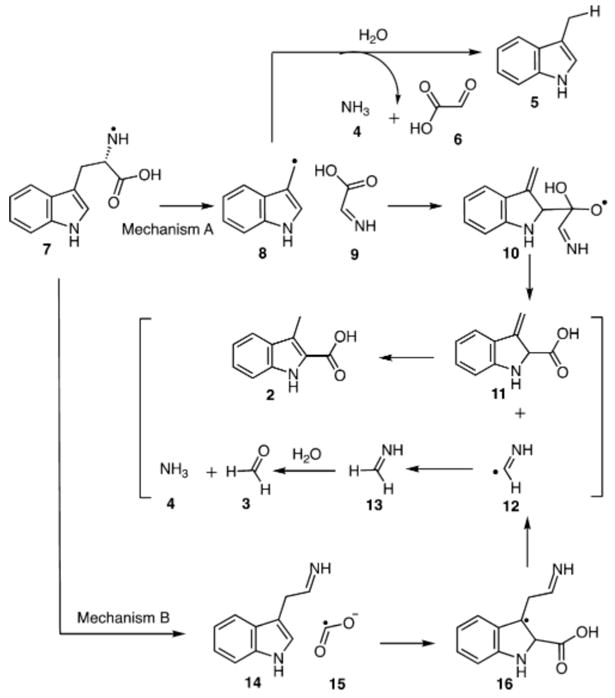

Tryptophan lyase (NosL) catalyzes the complex rearrangement of L-tryptophan (1) to 3-methylindole-2-carboxylic acid (2), a component of the nosiheptide antibiotic (Figure 1).1 This enzyme is a radical SAM enzyme in the same family of aromatic amino acid lyases as ThiH (thiamin biosynthesis), HydG (Fe–Fe hydrogenase maturation) and CofH (F420 biosynthesis).2 Recent structural3 and biochemical studies4,5 have demonstrated that the 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical (Ado•) of NosL abstracts a hydrogen atom from the amino group of L-tryptophan (1) and that the enzyme shows remarkable substrate tolerance.6–8 The current mechanistic proposals for this reaction are shown in Figure 2. In mechanism A,4,6,9 cleavage of the C2–C3 bond generates 8. Radical addition to the carboxylate carbonyl of 9 gives 10. A second β-scission reaction then gives 11, which tautomerizes to the final product 2. Reduction of the methanimine radical (12) by the [4Fe–4S]+1 cluster followed by hydrolysis completes the reaction. As a side product, 3-methylindole (5) is also produced in this reaction at levels that are sensitive to the reaction conditions and the substrate structure.1,4 In particular, 5 is the major product formed by the dithionite reduced enzyme (ratio of 5:2 is ~95:05). A mechanistic explanation for the control of the 5:2 ratio is not yet known. In Mechanism B, β-scission of 7 generates the formate radical (15), which then adds to C2′ of 14 to give 16. A second β-scission gives 11 and 12, which are converted to products as shown for mechanism A. Mechanism A is supported by substrate analog studies while Mechanism B is supported by substrate analog studies and the recent detection of 16 by EPR.10,11 In this Communication, we will describe three new experiments that support a variation of Mechanism B.

Figure 1.

NosL-catalyzed reaction as currently understood. Ammonia, formaldehyde and glyoxalate are the assumed byproducts.

Figure 2.

Two proposed mechanisms for the NosL-catalyzed reactions.

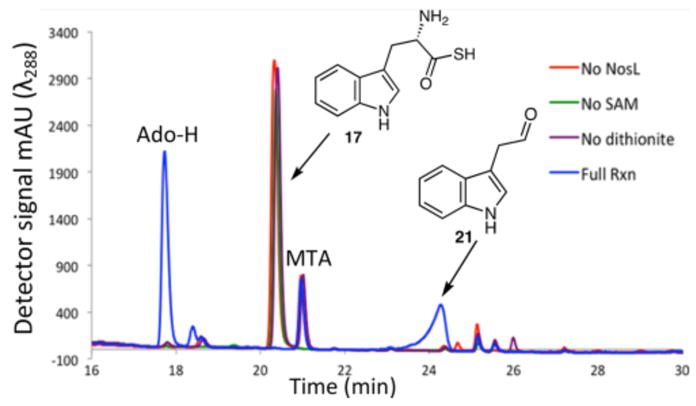

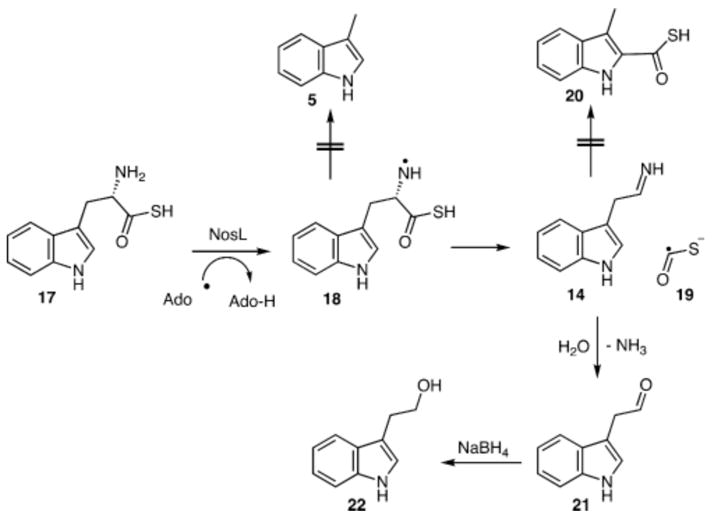

Replacing the tryptophan carboxylate with a thiocarboxylate is expected to favor formation of 20 over 5 if the reaction proceeds via Mechanism A because sulfur will stabilize 10 (OH bond is 18 kcal/mol stronger than the SH bond). In contrast, for Mechanism B, this substrate modification will retard the indole carboxylation because of thioformate radical (19) stabilization by the sulfur. This will facilitate the trapping of 14. When the NosL-catalyzed reaction was performed with tryptophan thiocarboxylate (17), HPLC analysis of the reaction mixture showed complete substrate consumption (Figure 3) and formation of a new product, which was identified as aldehyde 21 based on LC-MS analysis (Figure S4). This product was also reduced with NaBH4 to form alcohol 22, which was chromatographically identical with an authentic standard. Remarkably, 3-methylindole (5), the major product formed from L-tryptophan (1), was not detected.

Figure 3.

HPLC analysis of the NosL-catalyzed reaction with L-tryptophan thiocarboxylate (17). Ado-H, 5′-deoxyadenosine; MTA, 5′-methylthioadenosine (SAM degradation product).

A mechanistic proposal for this reaction is shown in Figure 4. In this proposal, β-scission of the C1–C2 bond of 18 generates 14 and the thioformate radical (19). Imine hydrolysis gives 21. Remarkably, this reaction does not yield any 3-methylindole (5), suggesting that addition of the formate radical to the indole precedes and is required for cleavage of the C2–C3 bond. Failure of the thioformate radical (19) to add to the indole is likely to be a consequence of the extra stabilization of the radical by delocalization into an empty d-orbital of sulfur (approximately 10 kcal/mol).12 In addition, the weaker hydrogen bonding of Arg323 to sulfur is likely to lower the efficiency of delivering thioformate (19) to the indole.

Figure 4.

Mechanistic proposal for the NosL catalyzed reaction with L-tryptophan thiocarboxylate (17). The thioformate radical (19) is converted to carbon dioxide (SI, Page 19).

We have previously observed the formation of aldehyde 21 in the reaction of D-tryptophan with NosL but viewed this fragmentation as an off-pathway reaction because of the altered tryptophan stereochemistry.4,13 Aldehyde 21, however, was not previously detected from L-tryptophan. Motivated by the results of the tryptophan thiocarboxylate experiment, we repeated the NosL/L-tryptophan reaction, using fluorescence rather than absorbance for product detection, to give greater sensitivity for the detection of aldehyde 21. HPLC analysis of the resulting reaction mixture showed a new signal at 24.3 min (Ex = 270 nm, Em = 352 nm) that comigrated with an authentic sample of 22 after NaBH4 reduction. LC-MS analysis confirmed the identification of this product as the aldehyde 21 (see Figure S5).

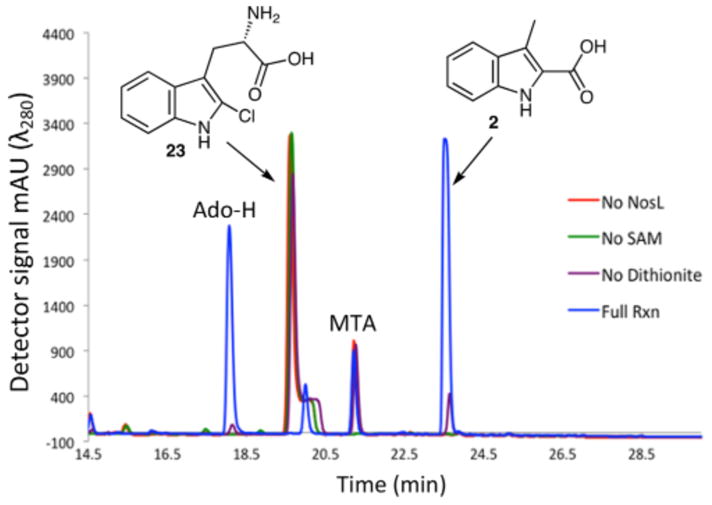

2′-Halo-L-tryptophan (Br, Cl) was designed to trap a radical on C3′ by exploiting the very rapid cleavage of a C-halogen bond beta to a radical center.14,15 When the NosL reaction was carried out with 2′-chloro-L-tryptophan (23), HPLC analysis showed complete substrate consumption and exclusive formation of a new product (Figure 5). This product was identified as 3-methylindole-2-carboxylic acid (2) by LC-MS and chromatographic identity to an authentic standard (see Figure S7). Similar results were obtained with 2′-bromo-L-tryptophan (24, see Figure S8). This is the first time we have observed the exclusive formation of 2 in a NosL-catalyzed reaction and demonstrates that tryptophan halogenation at C2 is one possible strategy for controlling the 5:2 ratio.

Figure 5.

HPLC analysis of the NosL reaction with 2′-chloro-L-tryptophan (23). The peak at 20 min in the full reaction mixture corresponds to 5′-deoxy-5′-thioadenosine whose formation has been previously described.7

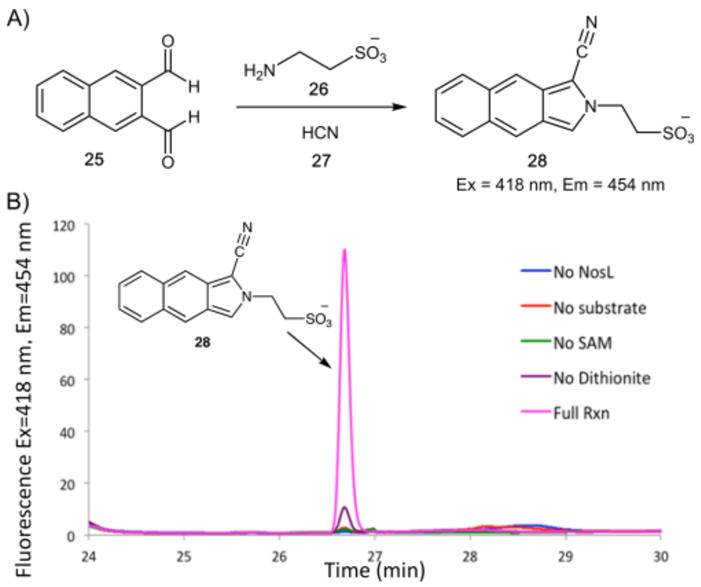

This reaction mixture was next analyzed for the products derived from C2 and the C2 amino group of 2′-chloro-L-tryptophan (23). Formaldehyde, carbon monoxide and cyanide were each considered as possible products. The enzymatic reaction, treated with purpald or dansylhydrazine failed to yield the corresponding formaldehyde adducts, thus excluding formaldehyde as a byproduct. Reduced hemoglobin also failed to detect carbon monoxide.16 To test for cyanide formation, the enzymatic reaction was treated with orthonapthalene dicarboxaldehyde (25) and taurine (26) to convert cyanide to the fluorescent derivative 28 (Figure 6).17 HPLC analysis using fluorescence (Ex = 418 nm, Em = 454 nm)18 showed a new product confirmed as 28 by LC-MS and chromatographic identity with an authentic standard (Figure S10). The ratio of cyanide to 3-methylindole-2-carboxylic acid was ~0.9:1.

Figure 6.

Detection of cyanide as a byproduct of the NosL-catalyzed reaction. (A) Reaction used to convert cyanide to a fluorescent product. (B) HPLC analysis of the NosL/2′-chloro-L-tryptophan (23) reaction mixture after derivatization as shown in panel A.

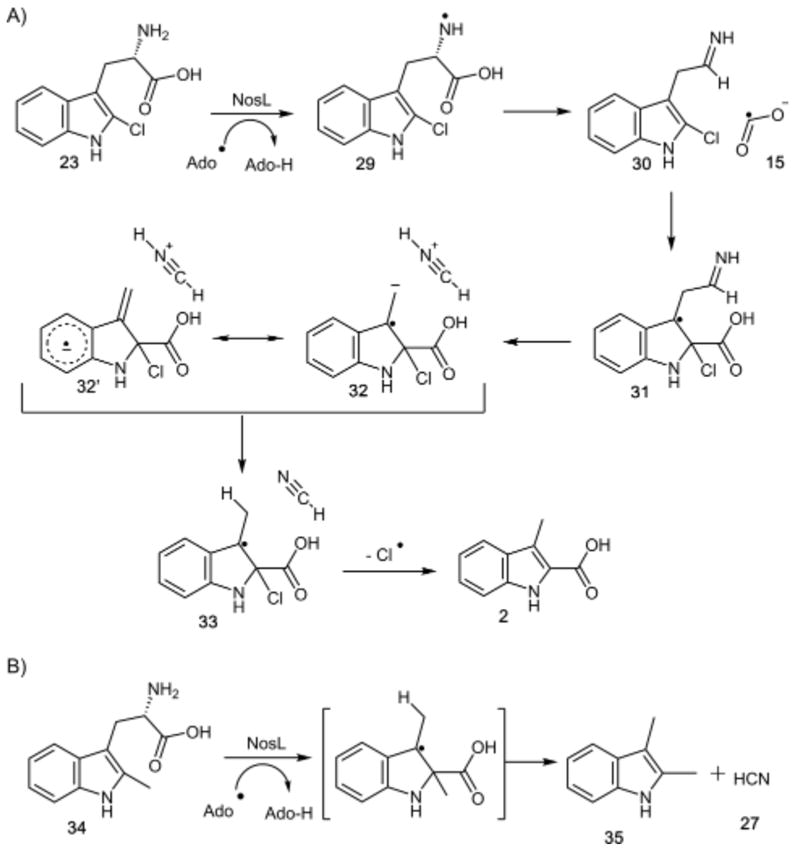

A mechanistic proposal for this reaction is shown in Figure 7A. Hydrogen atom abstraction from the amino group of 2′-chloro-L-tryptophan gives 29. A β-scission reaction releases the formate radical (15), which then adds to C2′ of the indole to give 31. Loss of H2CN+ from 31 gives the stabilized radical anion 32, which can also be viewed as an aryl radical anion 32′. Protonation at C3, potentially using the strongly acidic H2CN+, followed by loss of a chlorine atom completes the reaction. This proposal suggests that replacing the chloride with a methyl group would result in the formation of 2,3-dimethylindole (35) due to rapid decarboxylation of the methyl analog of intermediate 33. In fact, this is the observed product of 2′-methyl-L-tryptophan (34) with NosL (see Figures 7B and S11–S12).

Figure 7.

(A) Mechanistic proposal for the NosL-catalyzed reaction of 2′-chloro-L-tryptophan (23). (B) 2,3-Dimethylindole (35) and cyanide are the products generated during the NosL-catalyzed reaction with 2′-methyl-L-tryptophan (34).

Next, we turned our attention to the identification of the products of dithionite-reduced NosL with L-tryptophan (1). We previously established that 3-methylindole (5) is the major heterocyclic product of this reaction4 and glyoxalate (6) formaldehyde and ammonia (4) were assumed to be the C1/C2, the C2 and C2 amino-derived products respectively, based on the detection, at trace levels by LC-MS, of glyoxalate (6) and formaldehyde in the reaction mixture (Figure 1).1 The detection of cyanide as a NosL reaction product in the 2′-chloro-L-tryptophan (23) reaction cast doubt on this assumption.

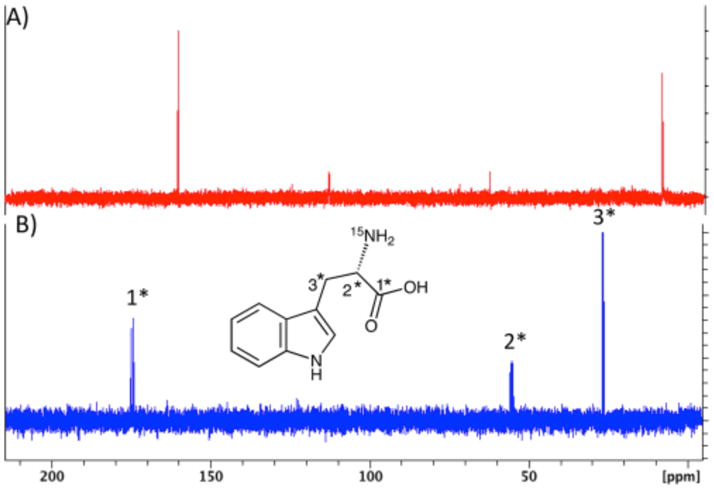

When the NosL reaction was performed with [1,2,3-13C3, 2-amino-15N]-L-tryptophan (prepared from labeled serine and indole using tryptophan synthase19), 13C NMR analysis of the reaction mixture revealed only two new signals (8 and 160 ppm, Figure 8A). The 8 ppm signal was assigned to the methyl group of 3-methylindole (5) and the 160 ppm signal was assigned to cyanide and/or bicarbonate by comparison with the spectra of authentic standards in reaction buffer.

Figure 8.

(A) 13C NMR of the NosL-catalyzed reaction with [1,2,3-13C3, 2-amino-15N]-L-tryptophan. (B) 13C NMR of [1,2,3-13C3, 2-amino-15N]-L-tryptophan standard.

Because the 160 ppm signal could not be unambiguously identified, we repeated the experiment using [1-13C1]-L-tryptophan. 13C NMR analysis of the resulting reaction mixture showed a single signal at 160 ppm that was identical to that of a spiked bicarbonate standard demonstrating that the carboxy group of tryptophan is converted to CO2 (see Figures S14–S15). This conclusion was further verified by demonstrating CO2 production using phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (see Figures S16–S19). To determine if cyanide is also a reaction product, the reaction mixture was treated with orthonapthalene dicarboxaldehyde (25) and taurine (26) (Figure 6A). HPLC and LC-MS analysis of this reaction mixture demonstrated the formation of the fluorescent product 28 ([M–H]− = 299 Da). When identical reactions were carried out using [15N]-L-tryptophan and [1,2,3-13C3, 2-amino-15N]-L-tryptophan, the masses of the fluorescent products ([M–H]−) were 300 and 301 Da, respectively (see Figures S20–S21). This is consistent with the conversion of C2 and the C2 amino group of L-tryptophan to cyanide (3-methylindole:cyanide ratio ~1:0.9).

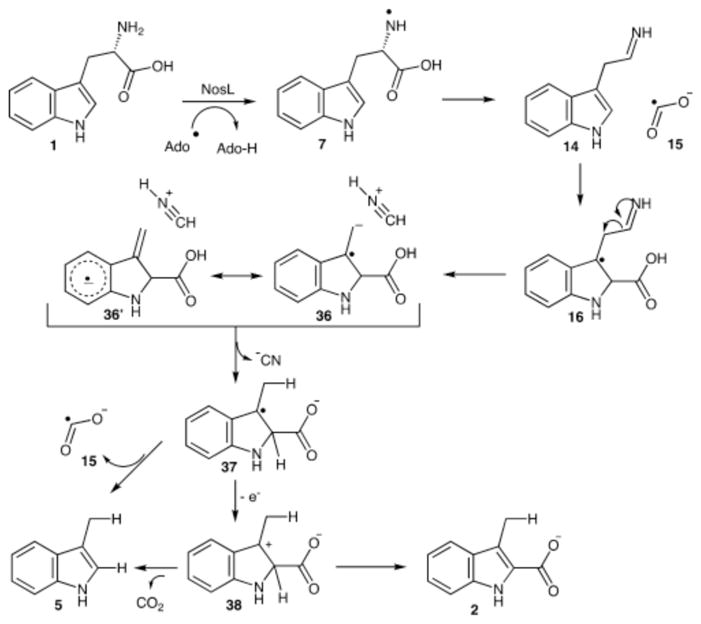

These results can be integrated into the mechanistic proposal for the NosL-catalyzed reaction with L-tryptophan (1) shown in Figure 9. In this mechanism, the initially formed amine radical (7) undergoes a β-scission reaction to form 14 and the formate radical (15), which then adds to the C2′ of the indole to form 16. Loss of H2CN+ by a second β-scission reaction gives 36, which can also be described as an aryl radical anion 36′. Protonation of this radical by the strongly acidic H2CN+ followed by electron transfer back to the [4Fe–4S]+2 cluster gives the cation 38. This can lose CO2 or a proton to give the experimentally observed reaction products 5 and 2 respectively. Alternatively, loss of a formate radical from 37 could also give 5. This mechanism is consistent with the EPR spectroscopy that provides evidence for the formation of 16. It is also consistent with the NosL reaction with L-tryptophan thiocarboxylate (17), which blocks the formation of 16 and demonstrates that the formation of 3-methylindole (5) can only occur after addition of the formate radical to the indole. Finally, it is consistent with the formation of 3-methylindole-2-carboxylic acid (2) as the sole product when 2′-chloro-L-tryptophan (23) is used as the substrate and with the formation of 2,3-dimethylindole (35) when 2′-methyl-L-tryptophan (34) is used as the substrate. The identification of cyanide as the product derived from the C2 and C2 amino group of tryptophan requires a major revision of the NosL mechanism and uncovers an unanticipated connection between NosL and HydG, the radical SAM enzyme that forms cyanide and carbon monoxide from tyrosine during the biosynthesis of the metallo-cluster of the [Fe–Fe] hydrogenase.20

Figure 9.

Mechanistic proposal for the NosL-catalyzed reaction that is consistent with the formation of cyanide from the C2 and C2 amino group of L-tryptophan.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Ron Trolard, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, provided [13C3,15N1]-L-serine as a generous gift. This research was supported by the Robert A. Welch Foundation (A-0034).

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.7b09000.

Detailed procedures for substrate synthesis, chemoenzymatic synthesis, enzymatic reaction conditions, HPLC and LC-MS chromatograms of all enzymatic reaction products, and NMR spectra of synthesized compounds (PDF)

References

- 1.Zhang Q, Li Y, Chen D, Yu Y, Duan L, Shen B, Liu W. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:154–160. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehta AP, Abdelwahed SH, Mahanta N, Fedoseyenko D, Philmus B, Cooper LE, Liu Y, Jhulki I, Ealick SE, Begley TP. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:3980–3986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.623793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolet Y, Zeppieri L, Amara P, Fontecilla-Camps JC. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2014;53:11840–11844. doi: 10.1002/anie.201407320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhandari DM, Xu H, Nicolet Y, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Begley TP. Biochemistry. 2015;54:4767–4769. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ji X, Li Y, Ding W, Zhang Q. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2015;54:9021–9024. doi: 10.1002/anie.201503976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ji X, Li Y, Jia Y, Ding W, Zhang Q. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2016;55:3334–3337. doi: 10.1002/anie.201509900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhandari DM, Fedoseyenko D, Begley TP. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:16184–16187. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b06139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ji X, Li Y, Xie L, Lu H, Ding W, Zhang Q. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2016;55:11845–11848. doi: 10.1002/anie.201605917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qianzhu H, Ji W, Ji X, Chu L, Guo C, Lu W, Ding W, Gao J, Zhang Q. Chem Commun. 2017;53:344–347. doi: 10.1039/c6cc08869d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding W, Ji X, Li Y, Zhang Q. Front chem. 2016:4. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2016.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sicoli G, Mouesca J-M, Zeppieri L, Amara P, Martin L, Barra AL, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Gambarelli S, Nicolet Y. Science. 2016;351:1320–1323. doi: 10.1126/science.aad8995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berkowitz J, Ellison G, Gutman D. J Phys Chem. 1994;98:2744–2765. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ji X, Liu W-Q, Yuan S, Yin Y, Ding W, Zhang Q. Chem Commun. 2016;52:10555–10558. doi: 10.1039/c6cc05661j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner PJ, Lindstrom MJ, Sedon JH, Ward DR. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:3842–3849. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joshi S, Mahanta N, Fedoseyenko D, Williams H, Begley TP. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:10952–10955. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b04209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chatterjee A, Hazra AB, Abdelwahed S, Hilmey DG, Begley TP. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:8653–8656. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tracqui A, Raul J, Geraut A, Berthelon L, Ludes BJ. Anal Toxicol. 2002;26:144–148. doi: 10.1093/jat/26.3.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Driesener RC, Challand MR, McGlynn SE, Shepard EM, Boyd ES, Broderick JB, Peters JW, Roach PL. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:1687–1690. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawasaki H, Bauerle R, Zon G, Ahmed S, Miles E. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:10678–10683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pagnier A, Martin L, Zeppieri L, Nicolet Y, Fontecilla-Camps JC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:104–109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515842113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.