Abstract

A paralog (here termed COG0212) of the ATP-dependent folate salvage enzyme 5-formyltetrahydrofolate cycloligase (5-FCL) occurs in all domains of life and, although typically annotated as 5-FCL in pro- and eukaryotic genomes, is of unknown function. COG0212 is similar in overall structure to 5-FCL, particularly in the substrate binding region, and has distant similarity to other kinases. The Arabidopsis thaliana COG0212 protein was shown to be targeted to chloroplasts and to be required for embryo viability. Comparative genomic analysis revealed that a high proportion (19%) of archaeal and bacterial COG0212 genes are clustered on the chromosome with various genes implicated in thiamin metabolism or transport but showed no such association between COG0212 and folate metabolism. Consistent with the bioinformatic evidence for a role in thiamin metabolism, ablating COG0212 in the archaeon Haloferax volcanii caused accumulation of thiamin monophosphate. Biochemical and functional complementation tests of several known and hypothetical thiamin-related activities (involving thiamin, its breakdown products, and their phosphates) were, however, negative. Also consistent with the bioinformatic evidence, the COG0212 proteins from A. thaliana and prokaryote sources lacked 5-FCL activity in vitro and did not complement the growth defect or the characteristic 5-formyltetrahydrofolate accumulation of a 5-FCL-deficient (ΔygfA) Escherichia coli strain. We therefore propose (a) that COG0212 has an unrecognized yet sometimes crucial role in thiamin metabolism, most probably in salvage or detoxification, and (b) that is not a 5-FCL and should no longer be so annotated.

Keywords: At1g76730, Chloroplast, COG0212, Thiamin, Folate

Introduction

With over 1,200 prokaryote and 100 eukaryote genomes now sequenced (Liolios et al. 2010), it has become starkly clear that genes of unknown or uncertain function outnumber those of known function in many genomes (Hanson et al. 2009; Janga et al. 2011). This “unknown gene function” problem is exacerbated by misannotations, in which functions are wrongly projected onto genes, based on sequence homology (Schnoes et al. 2009; Galperin and Koonin 2010). Most common are “overannotations” in which overly specific functions are assigned to relatively distant homologs—in fact paralogs—of genes of known function (Schnoes et al. 2009). Thus, while long-range homology is useful for assigning proteins to a general class (e.g., “dehydrogenase”), it is a poor guide to their precise functions (Frishman 2007; Janga et al. 2011). Overannotations have knock-on effects. First, they propagate as new genomes are added to databases, leading to a downward spiral of annotation accuracy (Schnoes et al. 2009). Second, they corrupt metabolic reconstructions, which seek to infer the metabolic capabilities of organisms from genome sequences (Durot et al. 2009).

During a comparative genomic analysis of folate synthesis and metabolism (de Crécy-Lagard et al. 2007), we noticed a striking case of a protein that is almost always annotated as having a precise function although there is no experimental evidence for this function and obvious reason to question it. This protein is classified in the Clusters of Orthologous groups database (Tatusov et al. 2003) as COG0212 (the name used from here on). COG0212 is typically annotated as the folate salvage enzyme 5-formyltetrahydrofolate cycloligase (5-FCL; EC 6.3.3.2, also called 5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolate synthetase), although it shares only ~30% identity with the 80-residue C-terminal region of canonical 5-FCL proteins.

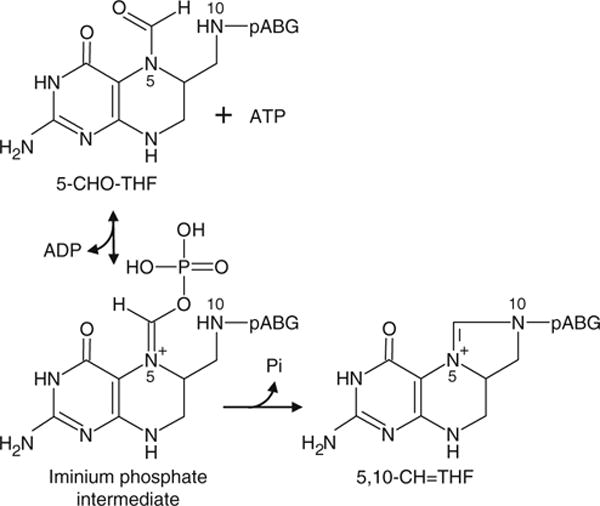

5-FCL metabolizes 5-formyltetrahydrofolate (5-CHO-THF), which is generated from 5,10-methenyltetrahydrofo-late (5,10-CH=THF) in a side reaction of serine hydroxymethyltransferase. Unlike other one-carbon (C1) folates, 5-CHO-THF is not a C1 donor but a potent inhibitor of many folate-dependent enzymes (Stover and Schirch 1993) and must consequently be removed. 5-FCL is the main enzyme known to do this, and ablating it leads to 5-CHO-THF accumulation (Holmes and Appling 2002; Goyer et al. 2005; Jeanguenin et al. 2010). 5-FCL is mechanistically a kinase, the initial reaction product being an iminium phosphate intermediate, which then undergoes cyclization and phosphate elimination to give back 5,10-CH=THF (Fig. 1; Field et al. 2007).

Fig. 1.

The mechanism of the reaction mediated by 5-FCL. Note that the first step is an ATP-dependent phosphorylation. 5-CHO-THF 5-formyltetrahydrofolate, 5,10-CH=THF 5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolate, pABG p-aminobenzoylglutamate

An initial survey of the distribution of COG0212 and 5-FCL genes revealed that plants, certain bacteria, and animals had both. This finding underscored the possibility that these proteins differ in function and established plants as representative models in which to study COG0212. Accordingly, we comprehensively surveyed the distribution of COG0212 and 5-FCL genes, investigated the essentiality and subcellular location of the plant COG0212 protein, used comparative genomics to predict possible metabolic functions for COG0212, and tested the predictions. A thiamin-related function was both predicted and supported experimentally, but a folate-related function was neither predicted nor found.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics

Genomes were analyzed using STRING (Jensen et al. 2009; http://string-db.org/) and the SEED database and its tools (Overbeek et al. 2005; http://theseed.uchicago.edu). COG0212 protein sequences were obtained from the NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and Joint Genome Institute (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/) databases. Sequences were aligned with ClustalW, and phylogenetic analyses were made with MEGA 4 (Tamura et al. 2007). Organellar targeting was predicted with TargetP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP/) and Predotar (http://urgi.versailles. inra.fr/predotar/predotar.html).

Chemicals

(6R,6S) 5-CHO-THF was obtained from Schircks Laboratories (Jona, Switzerland). Near-saturated stock solutions of 5-CHO-THF were freshly prepared in 25 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, excluding light, and titered spectrophotometrically (ε287 nm =31,500 M−1 cm−1; Temple and Montgomery 1984). [14C]Formate (52.5 mCi/mmol) was from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, CA, USA). Thiamin and its phosphates, oxythiamin, and 5-(2-hydroxyethyl)-4-methylthiazole (thiazole) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Oxothiamin (Thomas et al. 2008), 4-amino-5-hydroxymethyl-2-methylpyrimidine (HMP; Reddick et al. 2001), and N-formylpyrimidine (Jenkins et al. 2007) were synthesized as described.

COG0212 genes, proteins, and enzyme activity assays

Genomic DNA of Bacillus halodurans, Ochrobactrum anthropi, and Halobacterium sp. NRC-1 was from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Genomic DNA of Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 and Syntrophobacter fumaroxidans was from G. Shen (Pennsylvania State University) and C.M. Plugge (Wageningen University, The Netherlands), respectively. Arabidopsis thaliana COG0212 cDNA clone U82511 was from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC; Colum-bus, OH, USA). COG0212 sequences were amplified with PfuTurbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene) using genomic DNA or cDNAs as template and primers (Table S1) designed with restriction sites to insert the amplicons into pBluescript II SK (Stratagene) or pBAD24 (Guzman et al. 1995) for complementation assays or into pET28b (Novagen) for overexpression of proteins with a C-terminal His-tag. The A. thaliana sequence was truncated by using PCR to replace the first 150 bp by a start codon. Constructs were verified by sequencing. The production and isolation of recombinant COG0212 proteins and assays for thiamin- and folate-related enzyme activities are described in Online Resource 1.

Subcellular localization of A. thaliana COG0212

The full-length A. thaliana COG0212 cDNA or its first 327 bp (which includes the predicted targeting peptide) were cloned between SalI and NcoI sites in-frame upstream of the green fluorescent protein sequence in pTH2 (Niwa 2003). Preparation of A. thaliana mesophyll protoplasts, transfection, and subcellular localization of the fusion proteins were as described (Pribat et al. 2010). For dual import assays, the full-length A. thaliana COG0212 cDNA was cloned as an EcoRI-PstI fragment into pGEM-4Z (Promega) using a forward primer that included a Kozak sequence. Coupled in vitro transcription–translation, organelle separation, and dual import assays were as described (Rudhe et al. 2002; Pribat et al. 2010).

Isolation of A. thaliana COG0212 mutants

Two T-DNA insertional mutant lines (ecotype Columbia) for the gene (At1g76730) encoding COG0212 were identified in the Salk collection (SALK_037940 and SALK_037945). Seeds were obtained from the ABRC, sterilized for 1 min in 20% (v/v) bleach containing 0.1% SDS, and plated on MS medium (4.3 g/l MS salts, 1% sucrose, 0.35% Phytagel, pH 5.7). Germinated seedlings were transferred to potting medium and cultured in a growth chamber with an 8-h light period (250 μmol m−2 s−1) at 23°C and a 16-h dark period at 19°C. Wild-type and heterozygous mutant segregants from each line were identified by PCR screening using At1g76730 gene-specific primers located 5′ and 3′ of the insertion site and a primer located in the T-DNA (Table S1). Genomic DNA was isolated as described (Edwards et al. 1991) and amplified with Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). After 3 min at 95°C, the reaction was carried out with 30 cycles of 95°C for 45 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1.5 min (wild-type allele) or 45 s (mutant allele) and a final step at 72°C for 10 min. Insertion sites were confirmed by sequencing amplicons obtained from heterozygotes. Heterozygous mutant and wild-type segregants were selfed, and the progeny further analyzed. Siliques were split lengthwise with a razor blade and examined with a dissecting microscope. For germination assays, seeds were plated in lots of 50 on MS medium (plus or minus 1% sucrose) and scored after 10 days; results plus or minus sucrose were the same. Plantlets were transferred to potting medium and genotyped by PCR screening as above. Reciprocal crosses were made between wild-type and heterozygous plants. The resulting seeds were harvested, grown, and genotyped as above.

Deletion of Haloferax volcanii COG0212

H. volcanii strain H26 (a uracil auxotroph lacking the pyrE2 gene) was used to make the deletion. Cells were grown at 44°C (unless otherwise specified) in Hv-YPC, Hv-CA, or Hv-Min media (Dyal-Smith 2008). The deletion construct was designed to delete >80% of the COG0212 ORF (HVO_1928) by homologous recombination (El Yacoubi et al. 2009). A region from 1 kb before the start codon to the first 114 nucleotides of the ORF was amplified by PCR with primers Hv2Rev and Hv1Fwd, which includes a KpnI site (Table S1). A second region of 1 kb starting just after the stop codon was amplified with primers Hv3Fwd and Hv4Rev, which bears a BamHI site (Table S1). Both fragments were amplified from genomic DNA using Herculase (Stratagene) and 6% dimethyl sulfoxide, A-tailed with Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen), subcloned into pGEM-T (Promega), and sequence-verified. The two regions were assembled into pBluescript II SK (Stratagene) using their own above-mentioned restriction site and an internal pGem-T EcoRI site. The whole construct was excised with KpnI and BamHI, then cloned into pTA131 (Allers et al. 2004). Once obtained, the confirmed deletion plasmid was passed through a dam−strain of Escherichia coli (Inv110; Invitrogen) and transformed into H. volcanii H26 (or derivatives) using a polyethylene glycol-mediated protocol (Dyal-Smith 2008). Deletion of the targeted locus was selected for in a two-step process as described previously (Allers et al. 2004) (Fig. S1). Briefly, recombination of the deletion plasmid into the chromosome by a single cross-over event was selected for by growth on Hv-CA (i.e., in the absence of uracil). Subsequent excision of the integrated plasmid and target gene by a second recombination event was selected for by plating onto Hv-CA supplemented with uracil (10 μg ml−1) and 5-fluoroorotic acid (50 μg ml−1). PCR was used to confirm the deletion as follows: One pair of primers (Table S1) was designed to anneal in the regions flanking HVO_1928, and the amplicon size was compared to prediction for wild type and deletant. To confirm gene loss, a second pair of primers (Table S1) was designed to anneal within HVO_1928.

Functional complementation assays

Functional complementation of an E. coli ΔthiD strain was used to test for hydroxymethyl pyrimidine phosphate (HMP-P) kinase activity (Ajjawi et al. 2007). The E. coli HMP-P kinase deletant NI500 (ΔthiD) was obtained from the E. coli Genetic Stock Center (New Haven, CT, USA). E. coli ΔthiD cells harboring pACYC-RP were transformed with pBS II SK alone (negative control) or containing E. coli thiD (positive control) or a COG0212 gene (S. fumaroxidans, O. anthropi Oant_2976 or O. anthropi Oant_2980), plated on LB containing 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thio-galactoside (IPTG) and appropriate antibiotics, and incubated at 37°C. The next day, independent clones were streaked on M9 medium as above containing 0.2% (w/v) glucose, micronutrients, and FeSO4 and supplemented with 1 mM IPTG and 100 μg/ml of histidine, leucine, arginine, tryptophan, and methionine, plus or minus 10 μM thiamin. Plates were incubated for 4 days at 37°C. A functional complementation assay based on an E. coli ΔygfA strain (Jeanguenin et al. 2010) was used to test COG0212 proteins for 5-FCL activity. Details on this assay are given in Online Resource 1.

Vitamin analyses

For analysis of thiamin vitamers, the pellets obtained from 250 ml H. volcanii wild-type and COG0212 deletant cultures (OD600=0.7) grown in Hv-min medium without thiamin were resuspended in one volume of 7.2% perchloric acid and sonicated. The sonicate was held on ice for 15 min with periodic vortex mixing, then cleared by centrifugation at 4°C (2,000×g, 15 min). Thiamin and its phosphates were analyzed by oxidation to thiochrome derivatives followed by HPLC with fluorometric detection (Ishii et al. 1979). The oxidation reagent was a freshly prepared solution of 12.14 mM potassium ferricyanide in 3.35 M NaOH. Samples or standards (1 ml) were mixed with 100 μl methanol; 200 μl of oxidation agent was added, mixed for 30 s, and 100 μl of 1.43 M phosphoric acid was then added; the final pH was 6.9±0.2. The standards (thiamin and its mono- and diphosphates) were made up in 7.2% perchloric acid/0.25 M NaOH (1:1, v/v). Samples (50 μl) were separated on an analytical C18 column (100×4.6 mm, 3 μm particle size) eluted (1 ml min−1) with a gradient of 10–20% methanol/water (70:30, v/v) in 0.2 M KH2PO4 containing 0.3 mM tetrabutylammonium hydroxide, pH 7.0/methanol (88.5:11.5, v/v). Fluorometric detection wavelengths were 365 nm (excitation) and 435 nm (emission). Analysis of folate vitamers is described in Online Resource 1.

Results

COG0212 is an ancient, widely distributed paralog of 5-FCL

A survey of genomes in GenBank and the Joint Genome Institute (as of August 2010) showed that COG0212 proteins occur in plants (algae, mosses, lycopods, gymnosperms, angiosperms), animals (chordates, arthropods, annelids, mollusks, echinoderms), certain ascomycetes, many archaea, and a small number of taxonomically diparate bacteria. COG0212 appears not to occur in most fungi, protists, or some lower animals (nematodes, flatworms, cnidarians). Distribution data for 913 prokaryotes and representative eukaryotes are available at the SEED database http://theseed.uchicago.edu in the subsystem titled 5-FCL-like protein.

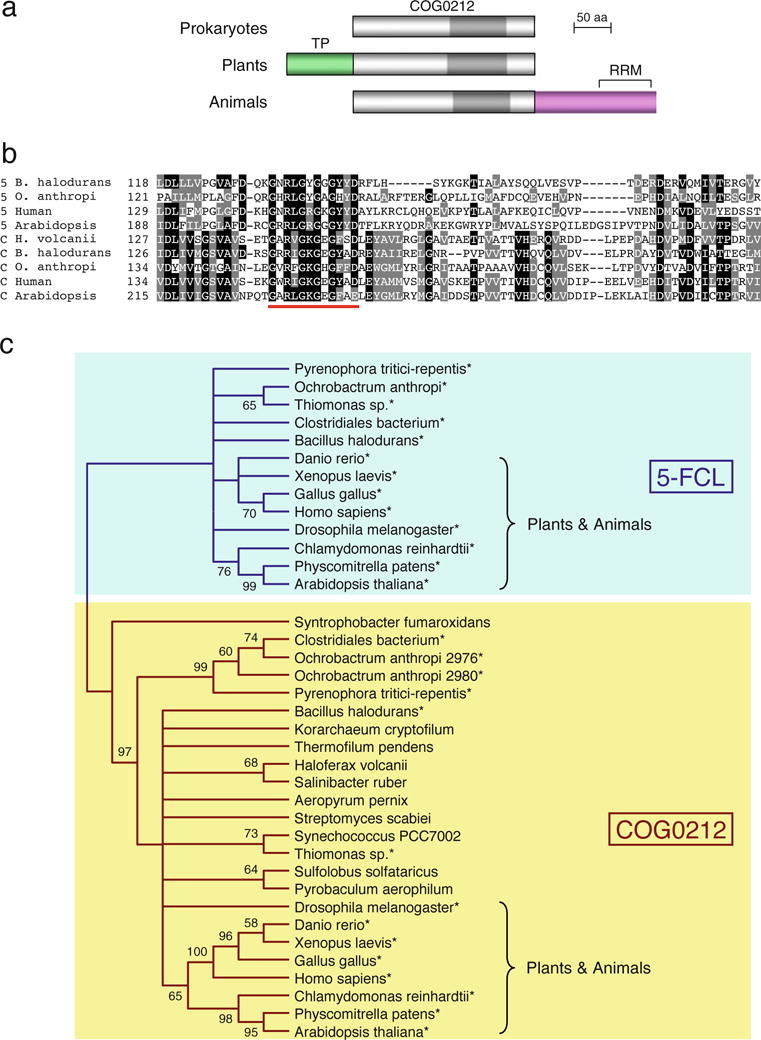

All COG0212 proteins share a domain of approximately 250 residues (Fig. 2a). In addition, plant proteins have a predicted N-terminal chloroplast targeting peptide, and most animal proteins have a C-terminal extension that, in chordates, contains an RNA recognition motif (RRM; Fig. 2a). RRMs are common, versatile domains that interact with nucleic acids or proteins (Maris et al. 2005). As noted above, COG0212 proteins have limited sequence similarity to 5-FCL proteins in a roughly 80-residue region toward the C terminus (Fig. 2b). The most conserved set of residues (underlined in red in Fig. 2b) correspond in 5-FCLs to the core of the active site that binds both 5-CHO-THF and ATP (Chen et al. 2004; Chen et al. 2005). In 5-FCLs, the penultimate residue of this conserved set is tyrosine, and changing it to alanine causes almost total (97–99%) loss of 5-FCL activity (Field et al. 2007; Wu et al. 2009). In contrast, the penultimate residue in COG0212 proteins is typically alanine or serine and never tyrosine (Fig. 2b). This single-residue difference, like the overall sequence divergence, suggests that COG0212 lacks 5-FCL activity and has some other function. Besides sharing homology with the active site region of 5-FCL, which is a kinase (Fig. 1), COG0212 proteins have long-range homology to other kinases, as detected by PSI-Blast (Altschul et al. 1997). Thus, whatever the specific function of COG0212 may be, it seems likely to involve an ATP-dependent phosphorylation.

Fig. 2.

Primary structure and phylogeny of COG0212 and 5-FCL proteins. a Comparison of the domain structures of prokaryotic, plant, and animal COG0212 proteins. Note the common core domain, the predicted targeting peptide (TP) in plants, and the C-terminal extension that in chordates contains an RNA recognition motif (RRM). Insect proteins have a longer C-terminal extension without an RRM motif. The positions of the conserved regions in the alignment below are marked in darker gray. b Amino acid sequence alignment of the conserved regions of representative 5-FCL (5) and COG0212 (C) proteins. Identical residues are shaded in black, similar residues in gray. Dashes are gaps introduced to maximize alignment. The most conserved set of residues is underlined in red. Full names of prokaryotes: Bacillus halodurans, Ochrobactrum anthropi, Haloferax volcanii. The COG0212 sequence from O. anthropi is Oant_2976. c Unrooted neighbor-joining tree for COG0212 and 5-FCL proteins. Only nodes with bootstrap values (1,000 replicates) of >50% are indicated; values are shown next to nodes. Only the tree topology is shown, so that branch lengths are not proportional to estimated numbers of amino acid substitutions. Species with both COG0212 and 5-FCL sequences in the tree are marked with asterisks

Phylogenetic analysis of pro- and eukaryotic COG0212 and 5-FCL proteins, including many that co-occur in the same genomes, shows that they belong to separate clades (Fig. 2c). The COG0212 and 5-FCL families are thus anciently diverged paralogs, which again suggests different functions. Within the COG0212 clade, most eukaryote proteins robustly branch together, whereas for prokaryotes the deeper branches of the tree are largely unresolved. As a group, COG0212 proteins are highly conserved. Thus, pairwise sequence comparisons between COG0212 proteins typically show higher percent identities than those between 5-FCL proteins from the same genomes (Fig. S2). As very diverse 5-FCL proteins are known to be isofunctional (Holmes and Appling 2002; Chen et al. 2005; Jeanguenin et al. 2010), the greater sequence conservation of COG0212 proteins implies that they may likewise be isofunctional.

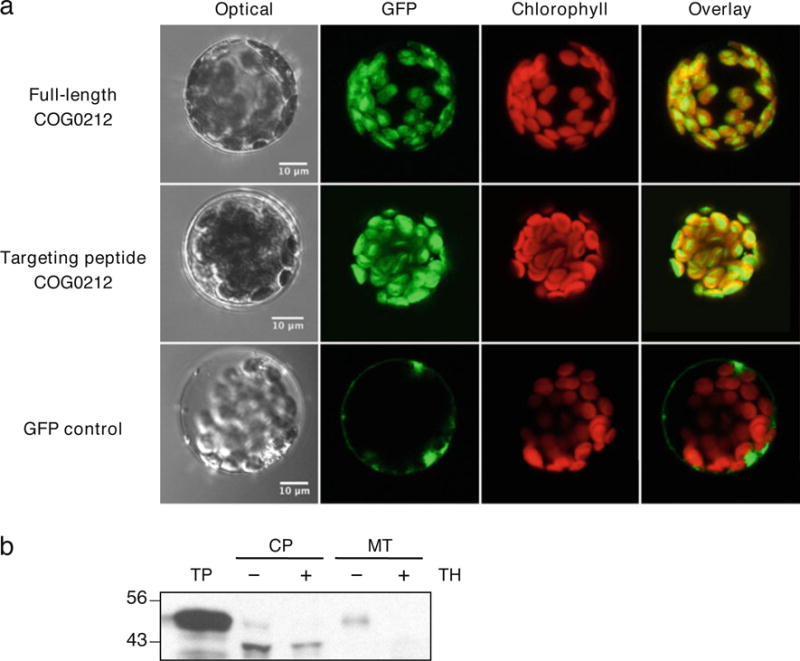

The plant COG0212 protein is chloroplast-localized

That plant COG0212 proteins have an N-terminal extension with the properties of a chloroplast targeting peptide led us to test for organellar targeting using in vivo and in vitro approaches. When the full-length A. thaliana COG0212 protein (At1g76730), or its predicted targeting peptide (residues 1–109), were fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP), they directed GFP exclusively to chloroplasts in transient expression experiments with A. thaliana mesophyll protoplasts (Fig. 3a). Controls using GFP alone showed no organellar targeting (Fig. 3a). This result was substantiated by in vitro data from dual import assays (Rudhe et al. 2002) in which mixtures of isolated pea chloroplasts and mitochondria were incubated with radiolabeled full-length A. thaliana COG0212 (Fig. 3b). After incubation, chloroplasts contained a labeled product that was smaller in size than the full-length precursor and resistant to thermolysin digestion, as expected for a trans-located protein. No translocated protein was detected in mitochondria (Fig. 3b). A proteomics study of A. thaliana also detected the COG0212 protein in chloroplast stroma (Zybailov et al. 2008). The chloroplastic location of COG0212 contrasts with that of 5-FCL, which is mitochondrial in plants (Roje et al. 2002).

Fig. 3.

Evidence that the plant COG0212 protein is chloroplast-targeted. a Transient expression in A. thaliana mesophyll protoplasts of green fluorescent protein (GFP) fused to the C terminus of full-length A. thaliana COG0212 (upper panels) or to the predicted targeting peptide of A. thaliana COG0212 (middle panels) and GFP alone (lower panels). GFP (green pseudo-color) and chlorophyll (red pseudo-color) fluorescence were observed by confocal microscopy. Scale bars=10 μm. b Protein import into isolated pea chloroplasts and mitochondria. The full-length A. thaliana COG0212 sequence was translated in vitro in the presence of [3H]leucine. The translation products were incubated for 15 min in the light with chloroplasts (CP) and mitochondria (MT), which were then re-purified on an 8% (v/v) Percoll gradient, without or with prior thermolysin (TH) treatment to remove adsorbed proteins. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by fluorography. Samples were loaded on the basis of equal chlorophyll or mitochondrial protein content next to an aliquot of the translation product (TP). The positions of molecular mass standards (kilodaltons) are indicated

COG0212 is essential in A. thaliana

To assess the physiological significance of COG0212, we analyzed two A. thaliana T-DNA mutant lines from the Salk collection. PCR of genomic DNA confirmed that both lines had an insertion at the same site in the third exon (Fig. S3a). The seed of both lines obtained from ABRC contained only wild-type and heterozygous individuals, and no homozygous mutants were found in the progeny of heterozygotes of either line. Further analysis of one line showed that selfed heterozygotes gave only wild-type and heterozygous progeny in a ratio that was a good fit to 1:2 (Fig. S3b, c). This result is consistent with zygotic lethality. In agreement with this explanation, reciprocal crosses between heterozygous and wild-type plants gave almost equal numbers of heterozygous and wild-type progeny (Fig. S3d). The lethality was presumably manifested early in development because germination was normal (Fig. S3c) and siliques contained no malformed seeds. The essentiality of A. thaliana COG0212 again distinguishes it from 5-FCL, which is non-essential (Goyer et al. 2005).

Comparative genomics links COG0212 to thiamin, not folates

The evidence that COG0212 has an indispensable function in plants prompted us to apply comparative genomics analysis to predict what that function might be (Overbeek et al. 1999; Date and Marcotte 2003; Hanson et al. 2009). Exploratory work used the STRING database (Jensen et al. 2009); the bulk of the analysis was done with the SEED database and its tools (Overbeek et al. 2005). Both databases integrate evidence for associations between genes based on their physical clustering on the chromosome, their distribution among genomes (“phylogenetic profiles”), as well as postgenomic data. STRING is entirely pre-computed whereas the SEED is user-driven, more flexible, and consequently more powerful.

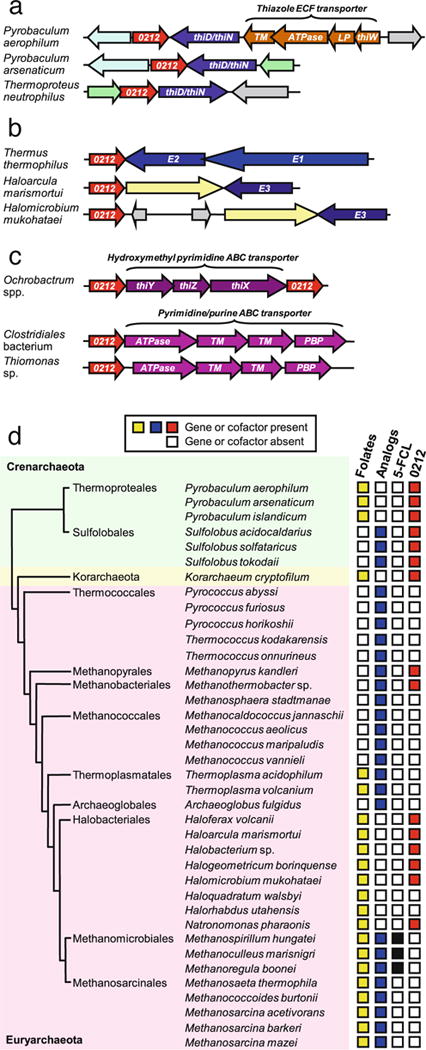

STRING predicted a medium to high confidence relationship with thiamin synthesis or salvage, based on an operonic arrangement in the archaeon Pyrobaculum islandicum of genes encoding COG0212 and the thiamin synthesis and salvage enzyme ThiD, which has both HMP and HMP-P kinase activities. Further analysis with SEED robustly implicated COG0212 in thiamin metabolism. First, the COG0212 gene in other archaea was found next to a fusion gene specifying ThiD and thiamin phosphate synthase (ThiN); in Pyrobaculum aerophilum, the gene cluster also includes an operon encoding an ECF-type transporter whose substrate capture component (ThiW) is predicted to bind the thiamin precursor thiazole (Rodionov et al. 2009; Fig. 4a). Second, the COG0212 gene in yet other archaea and the bacterium Thermus thermophilus is clustered with genes encoding one or more subunits of the thiamin pyrophosphate-dependent pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (Fig. 4b). Relatedly, the ATTED-II database (Obayashi and Kinoshita 2010) shows that A. thaliana COG0212 is coexpressed with pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (At3g06483), which regulates pyruvate dehydrogenase. Third, among bacteria with COG0212, O. anthropi and Ochrobactrum intermedium have operonic structures in which genes for two COG0212 proteins (having 40% identity) flank genes for the subunits ThiX-ThiY-ThiZ of an ABC transporter predicted to import the thiamin degradation products HMP and/or N-formylpyrimidine (Rodionov et al. 2002; Jenkins et al. 2007; Fig. 4c). The substrate binding component of this transporter (ThiY) shares sequence similarity with Thi3 of Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Thi5 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which are enzymes of HMP synthesis (Rodionov et al. 2002). Other bacteria have a single COG0212 gene in an operonic arrangement with genes for ABC transporters predicted to import pyrimidines (potentially including HMP), based on clustering with pyrimidine-related genes in other genomes. Examples include Thiomonas sp. and a Clostridiales bacterium (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Comparative genomic evidence associating COG0212 with thiamin metabolism and dissociating it from folate metabolism. a Clustering of archaeal COG0212 genes with genes for thiamin metabolism and transport. Arrows represent the direction of transcription. Colors denote homologous genes; gray denotes other genes. Note that the COG0212-thiD/thiN duplet is conserved despite changes in gene orientation and flanking genes. Genes of the predicted thiazole ECF family transporter: thiW substrate capture component, TM transmembrane component, ATPase ATPase component, LP lipoprotein component (Rodionov et al. 2009). b Clustering of bacterial and archaeal COG0212 genes with genes encoding one or more subunits (E1, E2, E3) of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, which requires thiamin pyrophosphate as cofactor. Color key as above. c Clustering of bacterial COG0212 genes with genes encoding components of ABC transporters predicted to import HMP and/or N-formylpyrimidine (Rodionov et al. 2002; Jenkins et al. 2007), or pyrimidines or purines. PBP periplasmic binding protein. In O. anthropi, the COG0212 gene on the left of the cluster is locus Oant_2980 and that on the right is Oant_2976. d Distribution among archaea of folates and folate analogs in relation to distribution of genes encoding 5-FCL and COG0212. The figure shows only species from genera in which chemical, biochemical, or genomic evidence supports the presence of folates or folate analogs such as methanopterin and sarcinapterin (Worrell and Nagle 1988; van de Wijngaard et al. 1991; White 1988, 1991, 1993; Gorris and van der Drift 1994; Lin and Sparling 1998; Lin and White 1988; Buchenau and Thauer 2004; Grochowski et al. 2007; Levin et al. 2007; Falb et al. 2008; Boroujerdi and Young 2009). The phylogeny is from Spang et al. (2010)

Because of the structural similarity between COG0212 and 5-FCL, we also searched for associations with genes of folate metabolism, beginning with phylogenetic profiles. Whereas virtually all eubacterial and eukaryote genomes with COG0212 encode a canonical 5-FCL protein, some archaea have COG0212, a few have 5-FCL, and many have neither (Fig. 4d). COG0212 and 5-FCL genes thus fail to show a reciprocal distribution pattern indicative of functional interchangeability (Fig. 4d). Moreover, only certain archaea (particularly class Halobacteria) have folates (Worrell and Nagle 1988; White 1991, 1993; Buchenau and Thauer 2004). The rest have methanopterins or other folate analogs whose chemistry differs from that of folates such that the analog of 5-CHO-THF (5-formylmethanopterin) is not metabolized via a reaction like that of 5-FCL (Maden 2000). Were COG0212 folate-dependent, it would therefore be expected to be confined to archaea with folates, but this is not the case (Fig. 4d). The phylogenetic profile of COG0212 thus adds to the evidence against its being a 5-FCL and further suggests that its function is not connected with folates. Additional negative evidence on this point is that prokaryotic COG0212 genes do not cluster with genes of folate synthesis, metabolism, or transport.

Experimental evidence implicating COG0212 in thiamin metabolism

Support for the prediction that COG0212 is linked to thiamin was sought using mutational, functional complementation, and biochemical approaches.

Analysis of H. volcanii COG0212 deletants

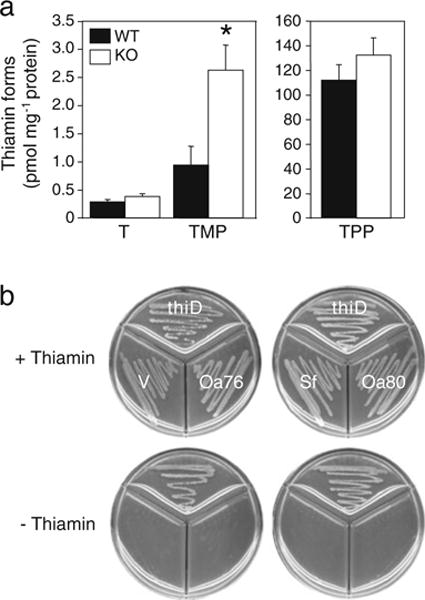

The archaeon H. volcanii has a single COG0212 gene (locus tag HVO_1928). This gene was ablated by targeted deletion (Fig. S4a, b). Deletant strains showed no growth phenotype on thiamin-free medium, showing that COG0212 is not required for de novo thiamin formation. Analysis of thiamin and its phosphates, however, showed a significant three-fold accumulation of thiamin monophosphate in deletant strains (Fig. 5a), which is consistent with a role for COG0212 in thiamin metabolism.

Fig. 5.

Experimental evidence implicating COG0212 proteins in thiamin metabolism. a Levels of thiamin (T), its monophosphate (TMP), and pyrophosphate (TPP) in H. volcanii COG022 knockout cells and wild-type controls. Data are means of three biological replicates; error bar shows the standard error of the mean. The asterisk indicates a significant difference (p<0.05; Student’s t test) between the wild type and knockouts. b Failure of COG0212 genes to functionally complement the E. coli ΔthiD strain. Cells were grown on M9 medium containing 0.2% glucose, plus or minus 10 μM thiamin. Note that the positive control, E. coli thiD, restored thiamin prototrophy. Sources of COG0212 genes: Sf S. fumaroxidans, Oa76 O. anthropi Oant_2976, Oa80 O. anthropi Oant_2980. V vector alone

Complementation and biochemical assays

A complementation assay was used to test for the capacity to phosphorylate HMP-P, which is needed for both salvage and synthesis. None of the three COG0212 genes tested restored thiamin prototrophy to an E. coli thiD (HMP phosphate kinase) deletant, although the positive control (E. coli thiD) did so (Fig. 5b). Thiamin is known to undergo numerous degradative reactions (Fig. S5), some of whose products are toxic, but this area of metabolism is little explored and salvage and detoxification enzymes are still being discovered (Jenkins et al. 2007; Jurgenson et al. 2009; Mukherjee et al. 2010). We therefore tested representative COG0212 proteins for several known and hypothetical activities involving thiamin, its breakdown products, and their phosphates; the reactions tested are summarized in Figures S6 and S7 and described in detail in Online Resource 1. No activity was detected for any of these reactions.

Experimental evidence that COG0212 is unconnected to folates

Experimental support for the bioinformatic predictions that COG0212 is neither a 5-FCL nor otherwise folate-related was sought using three approaches: functional complementation in E. coli, enzyme assays in vitro and in vivo, and folate analysis of recombinant or mutant strains. All gave negative results.

Functional complementation of a ygfA mutant

Ablation of the gene (ygfA) encoding 5-FCL in E. coli results in accumulation of 5-CHO-THF and inability to grow on minimal medium when glycine is the sole nitrogen source (Jeanguenin et al. 2010). This growth phenotype makes possible a complementation assay for genes encoding 5-FCL activity (or other activities that remove 5-CHO-THF). When six diverse COG0212 genes (from A. thaliana and various bacteria) were tested in this assay, none supported growth although the ygfA positive control did so (Fig. S8a). The A. thaliana COG0212 construct specified the predicted mature protein, i.e., without the targeting peptide.

Enzyme assays

Mature A. thaliana COG0212 and B. halodurans COG0212 were expressed in E. coli, and crude extracts were used to assay spectrophotometrically for 5-FCL activity (Fig. S8b). Neither protein showed activity although the positive control (A. thaliana 5-FCL) was active, as expected (Roje et al. 2002). Furthermore, HPLC analysis of COG0212 reaction mixtures detected no products of any kind. An in vivo [14C]formate fixation assay tested the possibility that COG0212 proteins have formate–tetrahydrofolate ligase activity, i.e., that they mediate the ATP-dependent coupling of formate to tetrahydrofolate. Expressing B. halodurans COG0212 in E. coli (which lacks formate–tetrahydrofolate ligase) did not confer [14C]formate fixation, and ablating the COG0212 gene in H. volcanii, which has formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase, did not impair [14C]formate fixation (not shown).

Folate analyses

To confirm that COG0212 proteins do not act on 5-CHO-THF and to screen for other folate-related activities, folate profiles were determined for the E. coli ΔygfA strain expressing A. thaliana or Synechococcus sp. COG0212, or vector alone. Cells were grown on rich (LB) or minimal (M9) medium. Expression of the COG0212 proteins did not significantly affect levels of 5-CHO-THF or other folates (Fig. S8c). Were, for instance, COG0212 to have 5-FCL activity, a reduction in 5-CHO-THF level would be anticipated (Jeanguenin et al. 2010). The folate profiles of H. volcanii COG0212 knockout strains were also analyzed; these displayed no accumulation of 5-CHO-THF or other changes relative to wild type (not shown).

Discussion

The comparative genomic and experimental evidence presented above establishes a positive connection between COG0212 and thiamin. Comparative genomic evidence shows that some 19% of prokaryotic COG0212 genes (from a total of 70 in GenBank as of August 2010) are clustered on the chromosome with one or more of a dozen genes that are known, or strongly inferred, to mediate metabolism and transport of thiamin or its precursors. The link to thiamin can be more specifically made to thiamin metabolism, not de novo synthesis, because (a) COG0212 occurs in animals, which cannot synthesize thiamin, and (b) COG0212 occurs in prokaryote and plant genomes that encode complete thiamin synthesis pathways (Rodionov et al. 2002; Goyer 2010). These arguments assume that animal, prokaryote, and plant COG0212 proteins are isofunctional; this seems warranted inasmuch as COG0212 proteins are more conserved than 5-FCL proteins that are known to be isofunctional (Fig. S2). The chloroplastic location of COG0212 is consistent with a role in thiamin metabolism because chloroplasts are the site of at least one thiamin salvage reaction (HMP phosphorylation) as well as several biosynthetic steps (Goyer 2010).

Experimental support for a role in thiamin metabolism as opposed to synthesis comes from the thiamin prototrophy of H. volcanii COG0212 knockout strains and from the expanded thiamin monophosphate pool in these strains. That the COG0212 knockout is lethal in A. thaliana is not necessarily inconsistent with its non-essentiality in H. volcanii. In plants and other higher organisms, particular cells or tissues often rely on others to synthesize essential metabolites de novo, being themselves capable only of salvage. A salvage defect in a critical cell type or developmental stage can therefore impact viability or growth. Indeed, thiamin itself provides an instance of this: Thiamin synthesis genes are barely expressed in roots, which cannot produce thiamin at a sufficient rate for growth (Goyer 2010).

The evidence for a role in thiamin metabolism—such as salvage or detoxification of a degradation product—prompted tests for certain known and hypothetical activities of this type, particularly those using ATP (based on the kinase-like structure of COG0212). That the results were negative by no means rules out a role for COG0212 in metabolizing thiamin breakdown products because this area is too poorly known to define the full set of reactions that should be tested; our exploratory work therefore covered only a subset of reasonable possibilities. More generally, it should be noted that salvage and detoxification are probably major but under-recognized facets of the metabolism of many labile compounds besides thiamin and that the enzymes involved are mostly still unidentified (Galperin et al. 2006). In sum, our bioinformatic and experimental data make it reasonable to infer that COG0212 mediates a reaction of thiamin metabolism, particularly salvage or detoxification of breakdown products, and that this reaction requires ATP. An accurate, informative annotation for COG0212 at this point would be “5-FCL paralog implicated in thiamin metabolism.”

Our comparative genomic, genetic, and biochemical evidence all make it unlikely that COG0212 proteins have 5-FCL activity or any other role in folate metabolism. There is consequently no justification for continuing to annotate COG0212 as being 5-FCL, or folate-related in any way.

Finally, it is informative to consider some negative consequences of misannotating COG0212 as “5-FCL” and what can be done to avoid such errors. In archaea, the misannotation confounds the vexed issue of which taxa have folates and folate-dependent enzymes and which do not. In mammals and plants, it falsely implies that there are two redundant 5-FCL enzymes to metabolize 5-CHO-THF. This error is significant in humans because 5-CHO-THF is widely used in cancer chemotherapy (Stover and Schirch 1993). In a wider sense, assigning a precise, superficially plausible but wrong annotation to a gene can deter further inquiry into its function and spark mistaken ideas about its biological role. As this study shows, such problems can be mitigated by using genome context evidence—gene clustering and phylogenetic distribution patterns in relation to those of other genes—to inform the annotation process instead of relying on sequence homology alone (Galperin and Koonin 2000).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by US National Science Foundation award # MCB-0839926 (to A.D.H.), by US Department of Energy award # FG02-07ER64498 (to V. de C.-L.), by NIH award # DK44083 (to T.P.B.), and by an endowment from the C. V. Griffin, Sr. Foundation. We thank S.E. Giuliani, D.M. Corgliano, and F.R. Collart for conducting exploratory ligand binding assays; A. Noiriel for making the H. volcanii deletion construct; K. Cline, C. Aldridge, and J.C. Waller for help with dual import experiments; and M. Ziemak for technical support.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10142-011-0224-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Anne Pribat, Horticultural Sciences Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA.

Ian K. Blaby, Microbiology and Cell Science Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA

Aurora Lara-Núñez, Food Science and Human Nutrition Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA.

Linda Jeanguenin, Horticultural Sciences Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA.

Romain Fouquet, Horticultural Sciences Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA.

Océane Frelin, Horticultural Sciences Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA.

Jesse F. Gregory, III, Food Science and Human Nutrition Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA.

Benjamin Philmus, Department of Chemistry, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77842, USA.

Tadhg P. Begley, Department of Chemistry, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77842, USA

Valérie de Crécy-Lagard, Microbiology and Cell Science Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA.

Andrew D. Hanson, Horticultural Sciences Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA

References

- Ajjawi I, Tsegaye Y, Shintani D. Determination of the genetic, molecular, and biochemical basis of the Arabidopsis thaliana thiamin auxotroph th1. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;459:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allers T, Ngo HP, Mevarech M, Lloyd RG. Development of additional selectable markers for the halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii based on the leuB and trpA genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:943–953. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.2.943-953.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroujerdi AF, Young JK. NMR-derived folate-bound structure of dihydrofolate reductase 1 from the halophile Haloferax volcanii. Biopolymers. 2009;91:140–144. doi: 10.1002/bip.21096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchenau B, Thauer RK. Tetrahydrofolate-specific enzymes in Methanosarcina barkeri and growth dependence of this methanogenic archaeon on folic acid or p-aminobenzoic acid. Arch Microbiol. 2004;182:313–325. doi: 10.1007/s00203-004-0714-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Shin DH, Pufan R, Kim R, Kim SH. Crystal structure of methenyltetrahydrofolate synthetase from Mycoplasma pneumoniae (GI: 13508087) at 2.2 Å resolution. Proteins. 2004;56:839–843. doi: 10.1002/prot.20214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Yakunin AF, Proudfoot M, Kim R, Kim SH. Structural and functional characterization of a 5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolate synthetase from Mycoplasma pneumoniae (GI: 13508087) Proteins. 2005;61:433–443. doi: 10.1002/prot.20591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Date SV, Marcotte EM. Discovery of uncharacterized cellular systems by genome-wide analysis of functional linkages. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1055–1062. doi: 10.1038/nbt861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Crécy-Lagard V, El Yacoubi B, de la Garza RD, Noiriel A, Hanson AD. Comparative genomics of bacterial and plant folate synthesis and salvage: predictions and validations. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:245. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durot M, Bourguignon PY, Schachter V. Genome-scale models of bacterial metabolism: reconstruction and applications. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2009;33:164–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyal-Smith M. The halohandbook: protocols for halobacterial genetics, Version 7. 2008 http://www.haloarchaea.com/resources/halohandbook/Halohandbook_2008_v7.pdf.

- Edwards K, Johnstone C, Thompson C. A simple and rapid method for the preparation of plant genomic DNA for PCR analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1349. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.6.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Yacoubi B, Phillips G, Blaby IK, Haas CE, Cruz Y, Greenberg J, de Crécy-Lagard V. A gateway platform for functional genomics in Haloferax volcanii: deletion of three tRNA modification genes. Archaea. 2009;2:211–219. doi: 10.1155/2009/428489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falb M, Müller K, Königsmaier L, Oberwinkler T, Horn P, von Gronau S, Gonzalez O, Pfeiffer F, Bornberg-Bauer E, Oesterhelt D. Metabolism of halophilic archaea. Extremophiles. 2008;12:177–196. doi: 10.1007/s00792-008-0138-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field MS, Szebenyi DM, Perry CA, Stover PJ. Inhibition of 5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolate synthetase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;458:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frishman D. Protein annotation at genomic scale: the current status. Chem Rev. 2007;107:3448–3466. doi: 10.1021/cr068303k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin MY, Koonin EV. Who’s your neighbor? New computational approaches for functional genomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:609–613. doi: 10.1038/76443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin MY, Koonin EV. From complete genome sequence to ‘complete’ understanding? Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28:398–406. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin MY, Moroz OV, Wilson KS, Murzin AG. House cleaning, a part of good housekeeping. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:5–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorris LG, van der Drift C. Cofactor contents of methanogenic bacteria reviewed. Biofactors. 1994;4:139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyer A. Thiamine in plants: aspects of its metabolism and functions. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:1615–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyer A, Collakova E, Díaz de la Garza R, Quinlivan EP, Williamson J, Gregory JF, 3rd, Shachar-Hill Y, Hanson AD. 5-Formyltetrahydrofolate is an inhibitory but well tolerated metabolite in Arabidopsis leaves. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26137–26142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grochowski LL, Xu H, Leung K, White RH. Characterization of an Fe2+-dependent archaeal-specific GTP cyclohydrolase, MptA, from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6658–6667. doi: 10.1021/bi700052a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose pBAD promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson AD, Pribat A, Waller JC, de Crécy-Lagard V. ‘Unknown’ proteins and ‘orphan’ enzymes: the missing half of the engineering parts list—and how to find it. Biochem J. 2009;425:1–11. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes WB, Appling DR. Cloning and characterization of methenyltetrahydrofolate synthetase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20205–20213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201242200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii K, Sarai K, Sanemori H, Kawasaki T. Analysis of thiamine and its phosphate esters by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1979;97:191–195. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janga SC, Díaz-Mejía JJ, Moreno-Hagelsieb G. Network-based function prediction and interactomics: the case for metabolic enzymes. Metab Eng. 2011;13:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanguenin L, Lara-Núñez A, Pribat A, Hamner Mageroy M, Gregory JF, 3rd, Rice KC, de Crécy-Lagard V, Hanson AD. Moonlighting glutamate formiminotransferases can functionally replace 5-formyltetrahydrofolate cycloligase. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:41557–41566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.190504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins AH, Schyns G, Potot S, Sun G, Begley TP. A new thiamin salvage pathway. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:492–497. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen LJ, Kuhn M, Stark M, Chaffron S, Creevey C, Muller J, Doerks T, Julien P, Roth A, Simonovic M, Bork P, von Mering C. STRING 8—a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D412–D416. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurgenson CT, Begley TP, Ealick SE. The structural and biochemical foundations of thiamin biosynthesis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:569–603. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.072407.102340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin I, Mevarech M, Palfey BA. Characterization of a novel bifunctional dihydropteroate synthase/dihydropteroate reductase enzyme from Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:4062–4069. doi: 10.1128/JB.01878-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Sparling R. Investigation of serine hydroxymethyltransferase in methanogens. Can J Microbiol. 1998;44:652–656. doi: 10.1139/cjm-44-7-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin XL, White RH. Distribution of charged pterins in nonmethanogenic archaebacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1988;150:541–546. [Google Scholar]

- Liolios K, Chen IM, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Hugenholtz P, Markowitz VM, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2009: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D346–D354. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maden BE. Tetrahydrofolate and tetrahydromethanopterin compared: functionally distinct carriers in C1 metabolism. Biochem J. 2000;350:609–629. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris C, Dominguez C, Allain FH. The RNA recognition motif, a plastic RNA-binding platform to regulate post-transcriptional gene expression. FEBS J. 2005;272:2118–2131. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee T, McCulloch KM, Ealick SW, Begley TP. Cofactor catabolism. In: Mander L, Liu H-W, editors. Comprehensive natural products II, chemistry and biology. Vol. 7. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2010. pp. 649–674. [Google Scholar]

- Niwa Y. A synthetic green fluorescent protein gene for plant biotechnology. Plant Biotechnol. 2003;20:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Obayashi T, Kinoshita K. Coexpression landscape in ATTED-II: usage of gene list and gene network for various types of pathways. J Plant Res. 2010;123:311–319. doi: 10.1007/s10265-010-0333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek R, Fonstein M, D’Souza M, Pusch GD, Maltsev N. The use of gene clusters to infer functional coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2896–2901v. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek R, Begley T, Butler RM, Choudhuri JV, Chuang HY, Cohoon M, de Crécy-Lagard V, Diaz N, Disz T, Edwards R, Fonstein M, Frank ED, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Goesmann A, Hanson A, Iwata-Reuyl D, Jensen R, Jamshidi N, Krause L, Kubal M, Larsen N, Linke B, McHardy AC, Meyer F, Neuweger H, Olsen G, Olson R, Osterman A, Portnoy V, Pusch GD, Rodionov DA, Rückert C, Steiner J, Stevens R, Thiele I, Vassieva O, Ye Y, Zagnitko O, Vonstein V. The subsystems approach to genome annotation and its use in the project to annotate 1000 genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5691–5702. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pribat A, Noiriel A, Morse AM, Davis JM, Fouquet R, Loizeau K, Ravanel S, Frank W, Haas R, Reski R, Bedair M, Sumner LW, Hanson AD. Nonflowering plants possess a unique folate-dependent phenylalanine hydroxylase that is localized in chloroplasts. Plant Cell. 2010;22:3410–3422. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.078824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddick JJ, Nicewonger R, Begley TP. Mechanistic studies on thiamin phosphate synthase: evidence for a dissociative mechanism. Biochemistry. 2001;40:10095–10102. doi: 10.1021/bi010267q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodionov DA, Vitreschak AG, Mironov AA, Gelfand MS. Comparative genomics of thiamin biosynthesis in procaryotes. New genes and regulatory mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48949–48959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208965200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodionov DA, Hebbeln P, Eudes A, ter Beek J, Rodionova IA, Erkens GB, Slotboom DJ, Gelfand MS, Osterman AL, Hanson AD, Eitinger T. A novel class of modular transporters for vitamins in prokaryotes. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:42–51. doi: 10.1128/JB.01208-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roje S, Janave MT, Ziemak MJ, Hanson AD. Cloning and characterization of mitochondrial 5-formyltetrahydrofolate cycloligase from higher plants. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42748–42754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205632200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudhe C, Chew O, Whelan J, Glaser E. A novel in vitro system for simultaneous import of precursor proteins into mitochondria and chloroplasts. Plant J. 2002;30:213–220. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnoes AM, Brown SD, Dodevski I, Babbitt PC. Annotation error in public databases: misannotation of molecular function in enzyme superfamilies. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spang A, Hatzenpichler R, Brochier-Armanet C, Rattei T, Tischler P, Spieck E, Streit W, Stahl DA, Wagner M, Schleper C. Distinct gene set in two different lineages of ammonia-oxidizing archaea supports the phylum Thaumarchaeota. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover P, Schirch V. The metabolic role of leucovorin. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:102–106. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90162-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov RL, Fedorova ND, Jackson JD, Jacobs AR, Kiryutin B, Koonin EV, Krylov DM, Mazumder R, Mekhedov SL, Nikolskaya AN, Rao BS, Smirnov S, Sverdlov AV, Vasudevan S, Wolf YI, Yin JJ, Natale DA. The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinform. 2003;4:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple CT, Montgomery JA. Chemical and physical properties of folic acid and reduced derivatives. In: Blakley RL, Benkovic SJ, editors. Folates and pterins. 2nd. Vol. 1. Wiley; New York: 1984. pp. 61–120. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AA, De Meese J, Le Huerou Y, Boyd SA, Romoff TT, Gonzales SS, Gunawardana I, Kaplan T, Sullivan F, Condroski K, Lyssikatos JP, Aicher TD, Ballard J, Bernat B, DeWolf W, Han M, Lemieux C, Smith D, Weiler S, Wright SK, Vigers G, Brandhuber B. Non-charged thiamine analogs as inhibitors of enzyme transketolase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:509–512. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.11.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wijngaard WM, Creemers J, Vogels GD, van der Drift C. Methanogenic pathways in Methanosphaera stadtmanae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;64:207–211. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90596-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RH. Analysis and characterization of the folates in the nonmethanogenic archaebacteria. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4608–4612. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4608-4612.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RH. Distribution of folates and modified folates in extremely thermophilic bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1987–1991. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.6.1987-1991.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RH. Structures of the modified folates in the extremely thermophilic archaebacterium Thermococcus litoralis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3661–3663. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3661-3663.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worrell VE, Nagle DP., Jr Folic acid and pteroylpolyglutamate contents of archaebacteria. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4420–4423. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4420-4423.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Li Y, Song G, Cheng C, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, Shaw N, Liu ZJ. Structural basis for the inhibition of human 5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolate synthetase by N10-substituted folate analogues. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7294–7301. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zybailov B, Rutschow H, Friso G, Rudella A, Emanuelsson O, Sun Q, van Wijk KJ. Sorting signals, N-terminal modifications and abundance of the chloroplast proteome. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.