Abstract

Single mothers’ relatively high levels of poverty are well documented, but the role that intergenerational coresidence may play in mitigating this disadvantage is not well understood. In this paper, we use multiple rounds of a large national survey between 1986 and 2007 (n = 67,252) to evaluate the extent to which income sharing via intergenerational coresidence limits poverty among single mothers in Japan. Results indicate that conventional poverty rates based on single-mother households overstate the prevalence of poverty among single mothers by 12–20 percent as a result of excluding those who are coresiding with parents. We find no evidence that the prevalence of intergenerational coresidence has changed in a way that would offset the poverty-increasing effect of growth in single parenthood. Finally, we show not only that shared income is the most important factor in limiting poverty among single mothers living with parents, but also that many single mothers are coresiding with parents who are themselves economically disadvantaged. We discuss the implications of our findings for understanding relationships between rapid family change and poverty in countries like Japan, where public income support for single mothers is limited and where family support via intergenerational coresidence is both common and normative.

Introduction

Cross-national comparative research on the economic well-being of single mothers has focused primarily on earnings and public policy, paying little attention to the role of living arrangements and intra-familial provision of support. From this work, we know that single mothers are more likely to be in poverty in countries like the United States, where public income support is less generous, and less likely to be in poverty in countries like Sweden and the Netherlands, where public support is more generous (OECD 2011). We also know that the poverty rates of single mothers are higher in settings where women’s wages are relatively low compared to men’s (Christopher et al. 2012) and where policies are less supportive of work-family balance (Misra et al. 2012). In the absence of corresponding insights on the role of intergenerational coresidence, our ability to effectively document and understand cross-national differences in the economic well-being of single-mother families is limited in several important ways.

First, it is difficult to make meaningful cross-national comparisons of the economic circumstances of single mothers. Because official statistics on poverty and other common measures of economic well-being are calculated at the household level (OECD 2011), standard poverty measures likely overstate the economic disadvantage of single mothers in countries where coresidence (and associated income sharing) with other family members is relatively common. Second, it limits our ability to assess the generality of well-documented relationships between the growing prevalence of single-mother families and aggregate-level trends in poverty observed in the United States. Are the implications of growth in single-mother families for aggregate levels of poverty less pronounced in societies where intergenerational coresidence and associated income sharing are more common? Third, it limits our understanding of the extent to which the relative importance of earnings, public income support, and intergenerational coresidence in shaping the economic well-being of single mothers (and their children) may differ across social, political, and economic contexts.

To address these limitations, we focus on Japan—a country that resembles the United States and many other Western countries in several key respects (e.g., rising income inequality, growing prevalence of single-mother families, high rates of poverty among single mothers, and limited public income support for families) but differs markedly in both the prevalence and normativity of intergenerational coresidence. The sharing of resources and the provision of support via intergenerational coresidence is one strategy that families have used to mitigate the impact of a diverse array of major social and economic changes, including women’s increased labor-force attachment (e.g., Morgan and Hirosima 1983), growing employment uncertainty for young adults (Mitchell 2006), the HIV/AIDS epidemic (Abebe and Aase 2007), and rapid population aging (Bengtson 2001). This is particularly true in “familistic” societies like Japan, and recent research suggests that the sharing of resources via coresidence may be a particularly important strategic family response to the rise in single motherhood (Shirahase 2013). However, research focusing explicitly on the role of intergenerational coresidence in mitigating economic disadvantage among single mothers is very limited (see Raymo and Zhou [2012] for one example).

Using data from multiple rounds of a large national survey, we begin by calculating a revised version of the poverty rate among single mothers in order to assess the extent to which official figures based on single-mother households overstate the actual level of economic deprivation among single mothers. We then use comparable data for the period 1986–2007 to ascertain the extent to which trends in intergenerational coresidence may have limited the impact of the growing prevalence of single-mother families on trends in poverty. Third, we use detailed data on income source to evaluate the relative importance of market earnings, public income support, and income sharing via intergenerational coresidence in shaping the economic well-being of single mothers. Results of these analyses provide an improved understanding of family change and poverty in Japan, an empirical basis for evaluating the generality of relationships between intergenerational coresidence and single mothers’ economic well-being in the United States and other countries, and insights to inform the development and extension of theories regarding family adaptation to rapid social change. Of particular importance are insights regarding the role of family support (via coresidence) for single mothers in “familistic” societies where public policy has long assumed a strong family safety net (Dalla Zuanna and Micheli 2004) and in societies where policy shifts have reduced public income support for vulnerable subpopulations.

Background

Single Mothers, Living Arrangements, and Poverty in the United States

Because research on the living arrangements of single mothers in Japan is scarce, we develop a theoretical and empirical foundation for this study by drawing on the large body of related research in the United States. Much of the early research in this area focused on African American families (e.g., Furstenberg, Brooks-Gunn, and Morgan 1987; Stack 1974), given the relatively high prevalence of single motherhood, poverty, and intergenerational coresidence in this subpopulation. More recent studies have shown that intergenerational coresidence is positively associated with single mothers’ economic well-being (e.g., Brown and Lichter 2004; Mutchler and Baker 2009), reflecting shared economic resources and economies of scale as well as access to childcare and social and emotional support (Baydar and Brooks-Gunn 1998; Casper and Bianchi 2002; Sigle-Rushton and McLanahan 2002). It also appears that the positive association between coresidence and economic well-being is offset to some extent by patterns of selection, with coresidence more common among young never-married mothers, those with limited earnings potential and lower levels of welfare receipt, and women whose parents also have limited economic resources (Edin and Lein 1997; Gordon 1999; Kaestner, Korenman, and O’Neill 2003).

Intergenerational coresidence, or “doubling up,” and the associated sharing of resources, has emerged as an important focus in research on the economic well-being of single mothers in the United States. This reflects growth in the number of single mothers, reductions in public income support and increased maternal labor-force participation following welfare reform, and the limited earnings potential of many single mothers (e.g., Blank 2006; Ellwood and Jencks 2004). It is also motivated by evidence that the poverty rates of single mothers are several times higher than for the population as a whole (Cancian and Reed 2009) and that the rise in single parenthood has contributed to increasing inequality and poverty (Blank 2011; Karoly and Burtless 1995; Martin 2006; but see Iceland [2003] and Western, Bloome, and Percheski [2008] for evidence that the role of family structure has been relatively limited in the 1990s and beyond).

It is clear that welfare reform has led to increased employment among single mothers and associated growth in earnings and overall economic well-being (Blank 2006; Lichter and Crowley 2004), but it is also true that market income is often not sufficient to reduce poverty or material hardship among single mothers (Bauman 2000; Nichols-Casebolt and Krysik 1997), and a substantial proportion of single mothers continue to face significant economic hardship (Blank 2006; Teitler, Reichman, and Nepomnyaschy 2004). For these women, intergenerational coresidence appears to provide an important buffer against further disadvantage. Using different sources of data, Haider and McGarry (2006) and Magnuson and Smeeding (2005) both conclude that intergenerational coresidence and associated sharing of income and housing are the most important source of economic resources for many of the most disadvantaged single mothers.

Expanding our understanding of the role of intergenerational coresidence is vital, given the centrality of relationships between single parenthood and poverty to both policy development and social scientific theory. In many countries, including the United States and Japan, recent policy efforts have focused on developing and implementing cost-effective means of supporting children and childcare, improving women’s (and men’s) ability to balance work and family, and promoting marriage (Lichter, Graefe, and Brown 2003). Scholarly interest in poverty among single mothers includes implications for theoretical understanding of economic inequality, gender inequality, children’s well-being, and the reproduction of disadvantage. For example, recent theorization about a second demographic transition highlights the implications of socioeconomic bifurcation in family behavior (including single parenthood) for the “diverging destinies” of children (McLanahan 2004). Similarly, gender-stratification research emphasizes the role of increasing single-parent families (the majority of which are headed by women) for trends in gender inequality (Casper, McLanahan, and Garfinkel 1994; Christopher 2002). In neither case, however, does this research address the potential role of intergenerational coresidence and associated support in shaping relationships between family change and economic well-being within or across generations.

Single Mothers in Japan

If we are interested in addressing these limitations, there is much to be learned from Japan, a country where single-mother families have increased in number, have high levels of poverty, and receive relatively little public income support. Of particular importance is the relatively high proportion of single mothers that coresides with parents. Japan differs from most Western countries in that intergenerational coresidence is a historically normative arrangement, and in that public-policy discussion often makes explicit reference to the role of family-provided support (Goodman and Peng 1996; Harada 1988; Osawa 2006). While perceptions of intergenerational coresidence as a “natural” or “obligatory” arrangement have declined over time (Ogawa and Retherford 1997), it is clear that coresidence and associated transfers of money and time remain an important strategy for providing economic support to family members in need.

In this context, we expect that income sharing via coresidence may be a particularly important resource for single mothers, and that poverty rates based on single-mother households may significantly overstate the degree of economic deprivation among single mothers (and their children). Japan thus provides an excellent setting in which to evaluate the generality of recent research on living arrangements and poverty among single mothers in the United States and to generate evidence that can inform the development of theory regarding the role of intergenerational coresidence as a form of family adaptation to the rise in single parenthood, especially in countries where public income support for this economically vulnerable population is limited.

Trends

The number of single-mother families (unmarried women with a coresident child under the age of 20) increased by 55 percent between 1993 (789,900) and 2011 (1,238,000) (Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare 2012). Among all households with children, the proportion headed by a single mother increased from 3.9 percent in 1980 to 9.5 percent in 2010 (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research 2012).

Because non-marital childbearing remains uncommon in Japan, the increase in single-parent families is due almost entirely to increases in divorce. The number of divorces nearly doubled, from 141,689 in 1980 to 251,378 in 2010 (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research 2012), and about one-third of marriages are now projected to end in divorce (Raymo, Iwasawa, and Bumpass 2004). As a result, the proportion of single-mother families formed via divorce increased from 49 percent in 1983 to 81 percent in 2011 (Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare 2012). The rise in single-mother families also reflects the fact that about 60 percent of all recent divorces involve children, and in 83 percent of these cases the mother receives full custody of all children (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research 2012). In 2011, 2 percent of births were registered to unmarried mothers and only 8 percent of single-mother families were formed via non-marital childbearing (Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare 2012).

Poverty

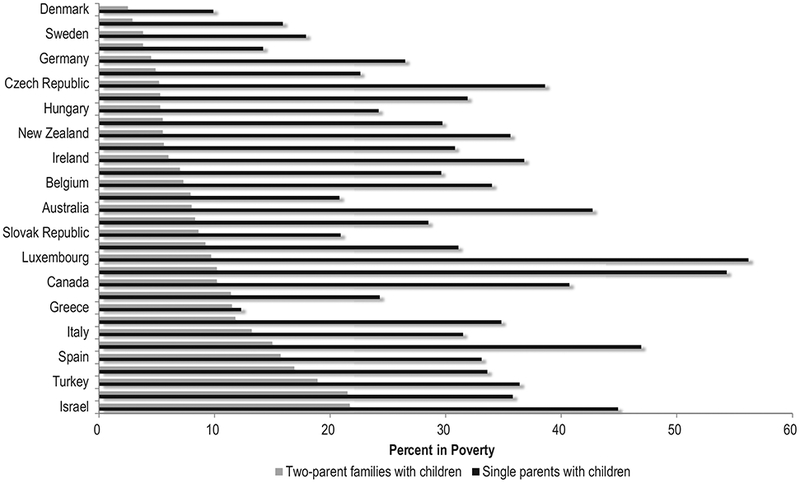

Figure 1 shows that single-mother households are economically disadvantaged in all OECD countries, and that the poverty rate is particularly high among single-mother households in Japan. Japan is one of only two countries in which over half of single-parent households fall below the poverty line (Luxembourg is the other), and per capita income in single-mother households is about half the amount for all households with children (Zhou 2008). This is despite high levels of labor-force participation. In 2006, 85 percent of single mothers in Japan were in the labor force, the second-highest figure among OECD countries (Zhou 2008).

Figure 1.

Poverty in OECD countries, by household type

Source:http://www.oecd.org/social/soc/oecdfamilydatabase.htm#INDICATORS.

The high rate of labor-force participation among single mothers in Japan reflects public policies characterized by relatively limited income transfers and a strong emphasis on independence through employment (Yuzawa and Fujiwara 2010; Ono 2010; Shirahase 2013). Limited public income support for single-mothers has been further reduced in recent years, resulting in lower benefits for almost half of all single mothers (Akaishi 2011). A five-year limit on eligibility for full benefits was also approved (Abe and Oishi 2005; Ezawa and Fujiwara 2005), but has yet to be implemented, due to strong public resistance. Priority for in-kind benefits, including job training and access to public housing and childcare, often favors single mothers (Ezawa and Fujiwara 2005), but the overall level of public support is low (Abe 2003; Osawa 2006; Tsumura 2002).

The high level of poverty among single mothers also reflects the types of jobs that are typically available to single mothers (Yuzawa and Fujiwara 2009). Of particular importance are women’s relatively low wages and limited job security (Brinton 2001), and the fact that a large majority of Japanese women leave the labor force prior to childbirth, and thus have discontinuous work histories. Among mothers with children under the age of six, single mothers were more likely than their married counterparts to have both exited and reentered the labor force (Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training 2012). As a result, many single mothers are employed in relatively unstable low-paying jobs, often on a part-time basis (Abe and Oishi 2005; Fujiwara 2007; Shirahase 2013; Tamiya and Shikata 2007). For example, data from the 2011 National Survey of Single-Mother Households show that only 40 percent of employed single mothers were working in regular, full-time jobs. Single mothers’ ability to engage in full-time, standard employment is also constrained by the fact that expectations of long work hours are common, commute times are often long, the operating hours of publicly provided childcare are limited, and the participation of non-custodial fathers in parenting is minimal (Abe 2008; Zhou 2008). In this context, it is perhaps not surprising that the poverty rate for single-mother households is largely unrelated to the mother’s employment status (Shirahase 2013).

Living Arrangements

Official statistics on single mothers refer to households headed by single mothers, and research on unmarried mothers in Japan often refers to them as “lone mothers” (e.g., Ezawa and Fujiwara 2005; Tokoro 2003), but it is clear that a substantial proportion of these women live with other adults, typically their parents. For example, in the 2011 National Survey of Single-Mother Households, 39 percent of single mothers were coresiding with another adult, and three-fourths of these women were living with their parents (Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare 2012). Data from the 2010 Census also indicate that 30 percent of single mothers were living with other adults, typically their parents (Nishi 2012). This figure is substantially higher than in other countries. For example, data from the Luxembourg Income Study (www.lisdatacenter.org) show that the proportion of single mothers coresiding with parents (or other relatives) in the middle of the first decade of the 2000s was .22 in the United States, .19 in Taiwan, .10 in Korea, .07 in the U.K, .04 in Italy, and .03 in Germany (authors’ tabulations).

Some recent work on Japan suggests that single mothers living with other adults may fare better than their counterparts living alone. For example, Raymo and Zhou (2012) found that single mothers living with other adults (typically parents) were less likely to report economic difficulties and more likely to report good health relative to their counterparts living alone. These relationships were robust to controls for observable characteristics associated with coresidence (e.g., younger, better-educated mothers are more likely to coreside), as well as efforts to control for the potential endogeneity of coresidence and well-being. Tabulations of data from the 2011 National Survey of Single-Mother Households showed that single mothers’ annual earnings were very similar for those living alone (1.82 million yen) and those coresiding (1.80 million yen), but other work has shown that the poverty rate is substantially lower for single mothers coresiding with parents (Shirahase 2013). We revisit this suggestive evidence in addressing the following three research questions:

Research Questions and Contributions

1: To what extent does the official poverty rate for single mothers overstate economic disadvantage by excluding those who coreside with their parents?

Because official poverty rates are based on household data, they likely overstate single mothers’ poverty in countries like Japan, where a substantial minority lives with other adults and are thus not included in the calculation of poverty rates for single-mother households. This is particularly true if economic deprivation is a primary motivation for coresidence, and if older (grand)parents are financially better off than single mothers. If we are interested in understanding how the economic circumstances of single mothers and their children vary across countries (and policy regimes), and in understanding how families adapt to rapid social change (especially in countries where public support for families is relatively limited), it is important to consider poverty measures that account for financial support via intergenerational coresidence. Efforts to this end will clearly depend on assumptions regarding the nature of sharing within the household. We follow previous studies in assuming full sharing of pooled income within the household (Short and Smeeding 2005), but recognize that this is an extreme assumption and consider the sensitivity of our results to alternative assumptions regarding the degree of income sharing.

2: To what extent have changes in living arrangements mitigated or exacerbated the effects of other factors contributing to trends in poverty among mothers in Japan?

Recent increases in poverty and inequality have received a tremendous amount of scholarly and media attention in Japan (e.g., Abe 2008; Iwata 2007; Ohtake 2005; Sato 2000; Shirahase 2013; Tachibanaki 1998), but little or no effort has been made to evaluate the role played by changes in family behavior. To address this limitation, we ask what the trends in poverty among mothers would have been in the absence of any change in living arrangements or marital status over a 20-year period. Results of this counterfactual exercise allow for an assessment of whether changes in family structure (i.e., the growth in single-mother families) contribute to an increase in poverty in a country where public income support for families is relatively weak and an evaluation of the extent to which trends in intergenerational coresidence may have limited the impact of growth in single-mother families on overall levels of poverty in a country where such arrangements are far more normative than in most other countries with large and growing populations of single mothers.

3: What is the relative importance of earnings, public income support, and intergenerational coresidence in limiting poverty among single mothers?

Again, this is a question that has received more attention in research on the United States than in other countries. This research has shown that the relative importance of public income support has declined, while that of mothers’ own earnings has increased (Haider and McGarry 2006). It is also clear that shared resources via coresidence are a major component of the economic resources of single mothers in the United States who do live with relatives. By examining this question in Japan, we seek to shed light on the role of familial support in settings where single motherhood is increasing, employment opportunities for single mothers are limited, and public policies are not designed to support new family structures like single-mother families. If we believe that family changes associated with the second demographic transition—including the rise in single-parent families—will spread widely to low-fertility countries in Asia or Latin America, where public support for families is often relatively weak, there is a clear value in understanding the role of coresidence in family adaptation to the rise in single parenthood in Japan.

Data

To address these three research questions, we use data from the Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions in Japan (CSLCJ). The CSLCJ is a nationally representative survey of households conducted annually by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare since the mid-1980s. A large-scale version of the survey, including information on the income and savings of all household members, has been conducted every three years since 1986. The poverty rates reported by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare and included in the OECD database are constructed using the CSLCJ data. We combine data across the eight surveys conducted between 1986 and 2007 and limit our analytic sample to households that include mothers living with their minor children, resulting in a sample of 67,252 households (or mothers). Applying sampling weights results in a weighted sample of 60,070,091 households/mothers across the eight survey years. The CSLCJ is well suited to our purposes, in that it includes information on marital status, relationship to household head, and income (by source) for all household members.

We begin by classifying mothers into four categories based on their marital status and the presence of coresident parents or other adult family members. Single mothers are defined as women who are divorced, widowed, or never married and are coresiding with at least one child under the age of 18. Because the survey instrument asks the household head to enumerate all household members who live together on a regular basis, we identify single mothers by their marital status rather than the presence/absence of a husband. A small number of women (n = 519, or 0.8 percent of all married mothers in our sample) report that they are married but their husband is not present due to work or other reasons and is thus not enumerated on the household roster. These women are not included in our analyses. Our dichotomous indicator of coresidential living arrangements distinguishes mothers who are living with adult family members (other than their spouse or their adult children) from those who are not. Household poverty is calculated using the OECD definition of relative poverty—household income that falls below one-half of the median post-transfer disposable equivalent income (with equivalent income calculated by dividing household income by the square root of household size). Household income includes inter-household transfers of money (although we cannot identify the source of those transfers) but does not include the value of in-kind transfers (this information was not collected in the CSLCJ). As described below, we address our research questions by comparing observed and counterfactual poverty rates across four groups of mothers: single mothers living alone, single mothers coresiding with parents, married mothers living with spouse only, and married mothers coresiding with parents(-in-law). Although not all mothers in the second and fourth categories are coresiding with parents(-in-law), we use this language for the sake of convenience. Because the vast majority of mothers living with other adults are core-siding with parents(-in-law) (90 percent of married mothers and 95 percent of single mothers), we think that the gain in clarity of expression outweighs the loss in accuracy. In most of the cases in which parents(-in-law) are not present, the “other adults” in the household are siblings (authors’ tabulations). This group also includes a small number of mothers who appear to be in cohabiting unions (i.e., coresiding with an unrelated male). In the 2007 round of the CSLCJ, there are only 2 such cases (weighted n = 1,458), representing 0.4 percent of all single mothers and 1.2 percent of single mothers coresiding with others. Cohabitation experience is increasing in Japan (Raymo, Iwasawa, and Bumpass 2009), but these unions tend to be short lived and often lead to marriage.

Table 1 presents descriptive information on marital status, coresidence with others, and poverty, by survey year. From these figures, we can see that the prevalence of unmarried mothers has increased substantially, from 3.7 percent of mothers in 1986 to 10.7 percent in 2007. The proportion of married mothers coresiding with parents(-in-law) declined steadily, from 18.8 percent (i.e., (18.1 ÷ 96.4) × 100 = 18.8) in the late 1980s to 13.1 percent in 2007, but the living arrangements of single mothers have remained relatively stable, with the proportion coresiding fluctuating between 27 and 36 percent across the 20-year period. In terms of poverty, it is clear that poverty rates are much lower among married mothers and that living arrangements matter for unmarried mothers but not for married mothers. For married mothers, the poverty rate is around 10 percent across years, regardless of living arrangements. For unmarried mothers, however, the poverty rate fluctuates more across time and is roughly twice as high among “lone mothers” as it is among those coresiding with parents. At the same time, the relatively high rates of poverty for the latter group (27–36%) suggest that, in many cases, the parents with whom single mothers coreside are themselves not economically well off.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics, by Marital Status, Living Arrangements, and Year

| Married | Unmarried | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not coresiding | Coresiding | Not coresiding | Coresiding | |

| 1986 | ||||

| Pct. of sample | 78.3 | 18.0 | 2.5 | 1.2 |

| Pct. in poverty | 8.3 | 10.7 | 59.5 | 28.7 |

| Weighted N | 9,384,889 | 2,160,285 | 296,906 | 138,587 |

| 1989 | ||||

| Pct. of sample | 77.0 | 18.2 | 3.4 | 1.4 |

| Pct. in poverty | 9.7 | 9.8 | 51.7 | 31.9 |

| Weighted N | 7,262,492 | 1,715,818 | 324,274 | 130,227 |

| 1992 | ||||

| Pct. of sample | 78.6 | 18.1 | 2.1 | 1.1 |

| Pct. in poverty | 10.2 | 10.3 | 55.0 | 31.4 |

| Weighted N | 7,055,008 | 1,622,881 | 189,934 | 102,515 |

| 1995 | ||||

| Pct. of sample | 78.0 | 16.4 | 4.0 | 1.5 |

| Pct. in poverty | 9.0 | 10.2 | 54.2 | 33.5 |

| Weighted N | 5,941,858 | 1,252,153 | 307,443 | 115,644 |

| 1998 | ||||

| Pct. of sample | 77.5 | 16.1 | 4.4 | 2.0 |

| Pct. in poverty | 10.4 | 7.2 | 64.8 | 28.5 |

| Weighted N | 5,195,445 | 1,080,184 | 293,409 | 135,008 |

| 2001 | ||||

| Pct. of sample | 78.0 | 15.1 | 4.9 | 2.0 |

| Pct. in poverty | 10.5 | 9.6 | 62.2 | 35.5 |

| Weighted N | 5,037,896 | 975,940 | 318,243 | 130,659 |

| 2004 | ||||

| Pct. of sample | 78.8 | 12.8 | 5.8 | 2.5 |

| Pct. in poverty | 9.7 | 8.7 | 61.4 | 27.5 |

| Weighted N | 3,632,025 | 591,947 | 265,723 | 117,099 |

| 2007 | ||||

| Pct. of sample | 77.7 | 11.7 | 7.4 | 3.2 |

| Pct. in poverty | 8.9 | 10.4 | 55.2 | 27.2 |

| Weighted N | 3,337,270 | 503,081 | 316,635 | 138,617 |

Method

We address our research questions through a series of counterfactual analyses. To evaluate the extent to which official poverty rates based on single-mother households overstate the level of poverty among single mothers in Japan (research question 1), we recalculate the poverty rate using information on all single mothers, including those coresiding with parents. From the figures in table 1, it is clear that this counterfactual rate will be lower than the “official” poverty rate because single mothers coresiding with parents (and thus not included in the official measure) are less likely to be in poverty.

To assess the role that changes in living arrangements have played in limiting the impact of growth in single-mother families on increasing levels of poverty between 1986 and 2007 (research question 2), we begin by expressing the poverty rate among mothers in a given year as

Pt: the number of mothers in poverty in year t, where t = 1986–2007

Nt: the total number of mothers in year t

Cijt: living arrangements in year t, i = not coresiding with parents, coresiding with parents, j = unmarried, married

Mjt: marital status j in year t

Pijt: the number of mothers in poverty in living arrangement i and marital status j in year t.

Using this equation, we can evaluate the impact of changes in living arrangements by counterfactually holding Cijt/Mjt constant at its 1986 values and recalculating the poverty rate for each year. Similarly, we can evaluate the impact of the other two components of change in the poverty rate—the increase in single-mother families and changes in the poverty rates of different groups of mothers—by counterfactually holding Mjt/Nt and Pijt/Cijt constant at their 1986 values and recalculating the poverty rate for each year. These counterfactual poverty rates allow for straightforward assessment of the extent to which observed changes in the poverty rate of mothers reflect compositional changes in living arrangements, the growing prevalence of single-mother families, and changes in group-specific poverty rates.

To evaluate the relative importance of market earnings, public income support, and economic resources provided by intergenerational coresidence in shaping the economic well-being of single mothers (research question 3), we begin by defining household income as the sum of mothers’ own income (excluding public transfer income), the income of other household members—that is, husband, parents, others (excluding public transfer income), and public transfer income. To evaluate the importance of mothers’ own income, we construct a new measure of household income after counterfactually setting mothers’ income to zero and then recalculate poverty rates for each of the four groups of mothers. Similarly, we evaluate the importance of public transfer income by setting this component of income to zero and comparing the poverty rates based on this counterfactual measure of household income with the observed poverty rates. Finally, and most importantly, we recalculate household income and poverty rates after counterfactually removing the income of other coresident family members. When calculating this third counterfactual measure of equivalent household income, we also remove other coresident adults from the denominator—household size (i.e., in this case, total household size is equal to the number of the mother’s children plus one). Stated differently, we counterfactually force single mothers coresiding with parents to become lone mothers. The magnitude of the difference between the observed poverty rates and these counterfactual poverty rates provides an intuitive metric for evaluating the importance of each income component in limiting poverty. Because detailed information on income by source is available only from 1995, we conduct this third set of analyses using data pooled across surveys for the period 1995–2007. This reduces our analytical sample to 31,390 mothers (weighted n = 29,686,276). Year-specific analyses (available upon request) show that little information is lost by pooling data across surveys in this manner.

Results

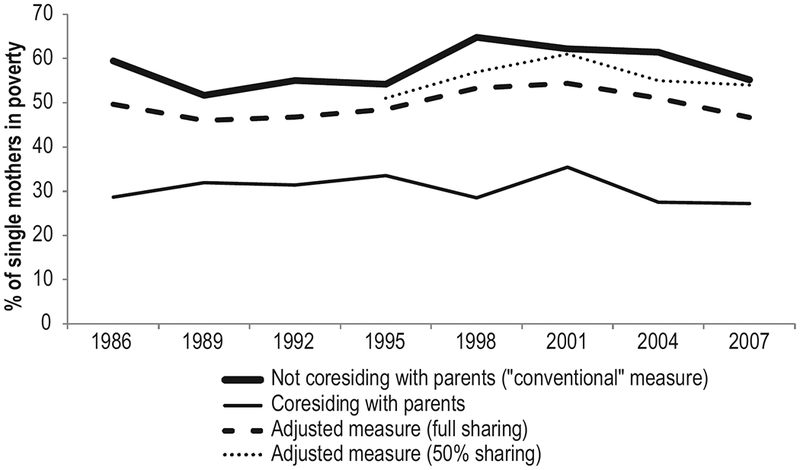

Figure 2 presents four poverty rates for single mothers over the period 1986–2007. The thick solid line corresponds to the conventional poverty rate, calculated based on single-mother households. Ranging between 52 percent in 1989 and 65 percent in 1998, these figures are very similar to those released by OECD and by the Japanese government. The thin solid line shows that the poverty rate of single mothers coresiding with parents is about half that for lone mothers. The thick dashed line shows the poverty rate for all single mothers. Comparing this modified poverty rate with the poverty rate based on single-mother households indicates that the latter “overstates” poverty among single mothers by 12–20 percent, depending on the year.

Figure 2.

Conventional and adjusted poverty rates for single-mother families, by year

Because this alternative poverty rate is based on the assumption of full income sharing among coresident household members, we also present figures calculated based on the assumption that single mothers have access to only half of the coresident parents’ income. The thin dashed line shows the proportion of all single mothers who fall below the poverty line when equivalent household income is calculated as mother’s income plus one-half of other coresident adults’ income divided by the square root of total household size and the poverty thresholds are those already calculated under the conventional assumption of full income sharing. This figure can be calculated only for the years in which detailed income information was collected for all household members (1995–2007). From this alternative measure, it is clear that conclusions regarding the importance of intergenerational coresidence in limiting poverty among single mothers are sensitive to assumptions about income sharing. The conventional poverty rate for single mothers is 12–20 percent higher than the alternative measure based on the assumption of full income sharing, but is only 2–14 percent higher than the measure that assumes partial (50 percent) sharing.

Although the poverty rates based on all single mothers are lower than the conventional rate, these more inclusive measures are still quite high, ranging from 46 to 54 percent under the assumption of full income sharing, and from 51 to 61 percent under the alternative assumption of partial sharing. This is consistent with previous studies that emphasize the heterogeneous economic circumstances of single mothers coresiding with parents, with some benefiting from the economic resources of relatively well-off parents while others are in the position of supporting parents who are themselves poor (Shirahase 2013). We provide additional evidence on the economic well-being of coresident (grand)parents below.

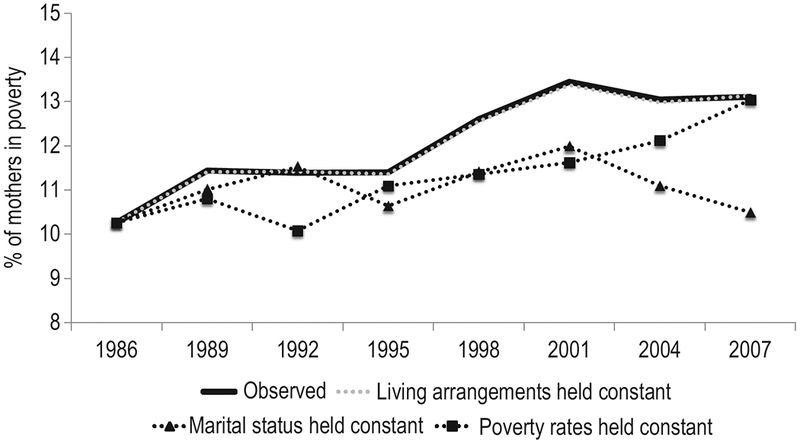

Figure 3 presents trends in the observed poverty rate for mothers of minor children and three counterfactual measures calculated by holding living arrangements, marital status, and group-specific poverty rates constant at their 1986 values. The thick black line shows that the overall poverty rate of mothers increased from 10 percent in 1986 to 13 percent in 2007. The gray dotted line showing the counterfactual poverty rates calculated by holding living arrangements at their 1986 values is nearly identical to the trend in observed poverty rates. This reflects the fact that coresidence with parents is unrelated to poverty among married mothers (who substantially outnumber unmarried mothers) and the fact that the prevalence of coresidence among single mothers remained stable at about 30 percent throughout the 20-year period covered by our data (as shown in table 1). Another interpretation of these results (in conjunction with the information presented in figure 2) is that the family (i.e., coresident (grand) parents) does play a role in limiting poverty among single mothers in Japan, but there is no evidence that the increase in single parenthood has been accompanied by a corresponding increase in family support (in the form of intergenerational coresidence and associated income sharing). These findings thus suggest that there are limits to families’ ability and/or willingness to support their most economically vulnerable members.

Figure 3.

Observed and counterfactual poverty rates for mothers, 1986–2007

The dotted line with triangle markers describes the poverty rate calculated by holding the marital-status distribution of mothers constant at its 1986 values. This set of counterfactual poverty rates shows that compositional change with respect to marital status was of limited importance through the early 1990s but accounts for a substantial proportion of the rise in mothers’ poverty since then. Indeed, nearly all of the observed difference in the 2007 and 1986 poverty rates can be “explained” by the higher prevalence of single mothers and their higher poverty rates.

The third set of counterfactual results (dotted line with square markers) shows what the poverty rate of mothers would have been if group-specific poverty rates had remained at their 1986 values. Changes in poverty among different groups of mothers explain the bulk of the relatively small increase in the overall poverty rate through 1995, about half of the rise in poverty between 1995 and 2001, and none of the difference between the poverty rates in 1986 and 2007. The contribution of group-specific poverty rates to trends in the overall poverty rate between 1995 and 2001 reflects the small rise in the poverty rates of single mothers, regardless of their living arrangements (as shown in figure 2). This pattern is likely attributable to particularly difficult employment circumstances of single mothers during Japan’s prolonged recession of the 1990s.

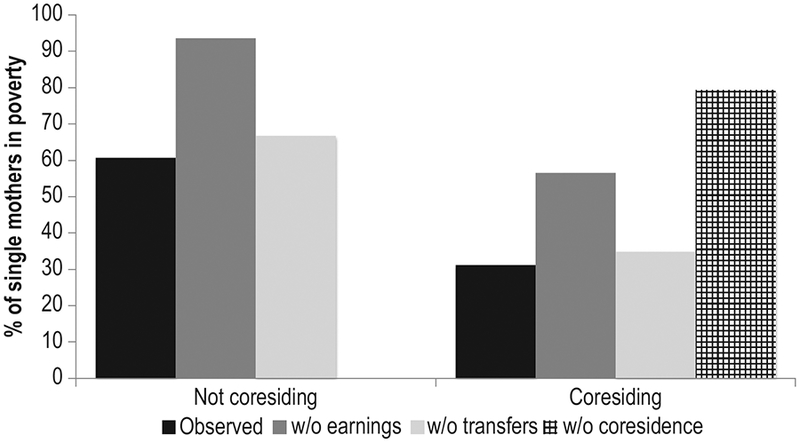

Figure 4 presents poverty rates for single mothers calculated by counterfactually removing different components of their (shared) income. These figures allow us to address our third research question regarding the relative importance of earnings, public income transfers, and income sharing via coresidence in determining the poverty rates of single mothers. We present figures separately for single mothers living alone (left) and those coresiding with parents (right). For both groups, the black bar represents the observed poverty rate for the period 1995–2007. Because we have pooled the data across surveys, these figures are weighted averages of the yearly values for each group presented in table 1 and figure 2.

Figure 4.

Observed and counterfactual poverty rates for single mothers, by living arrangements

The dark gray bars are the poverty rates calculated after removing single mother’s own income from total household income. Not surprisingly, earnings are a critical component of the economic well-being of lone mothers, whose poverty rate jumps from 61 to 94 percent when their own earned income is eliminated. For single mothers coresiding with parents, it is somewhat surprising that counterfactual elimination of their earnings nearly doubles the poverty rate, from 31 to 56 percent. This is further evidence that the parents with whom single mothers are coresiding often have low levels of economic well-being themselves. Auxiliary tabulations indicate that, in 20 percent of the households in which single mothers are coresiding with their parents, the parents themselves are below the poverty line. In 8 percent of cases, the addition of the single mother actually pulls the household out of poverty. In another 19 percent of cases, the addition of the poor single mother (and her children) pushes the household into poverty (results available upon request).

The light gray bars are the counterfactual poverty rates calculated after eliminating public income transfers. For both lone mothers and single mothers coresiding with parents, these counterfactual rates are slightly (10–12 percent) higher than the observed rates. Public income support thus plays a relatively limited role in mitigating the economic disadvantage associated with single motherhood in Japan. It is worth noting that these results are not inconsistent with other evidence showing that the post-transfer poverty rate of single-mother households is actually higher than the pre-transfer poverty rate (Abe 2008). Our calculations are based on disposable (post-tax) income and thus say nothing about the magnitude of net transfers. Auxiliary analyses (not shown) indicate that net transfers to lone mothers in these data are positive, but small. The average value of annual net public income transfers to lone mothers is roughly 100,000 yen ($1,000).

The hatched bar demonstrates that income sharing via coresidence is the most important source of income for limiting poverty among single mothers in these households. If we counterfactually remove single mothers from their coresidential household and recalculate poverty rates based on only their own income (including public transfer income) and a total household size equal to the number of mothers’ coresident children plus one, the poverty rate is 79 percent. As discussed above, the magnitude of the reduction in poverty due to coresidence (i.e., the difference between the black bar and the hatched bar) is exaggerated by our assumption of full income sharing within coresident households. Alternative assumptions about income sharing would result in a higher observed poverty rate (black bar) and thus a smaller inferred economic benefit of coresidence.

The fact that this counterfactual poverty rate calculated by removing single mothers from their parents’ home (79 percent) is higher than the observed poverty rate for lone mothers (61 percent) suggests either that single mothers who coreside with parents may be particularly disadvantaged or that the decision to coreside with parents results in (or is motivated by) a reduction in work hours and earnings. To evaluate the latter possibility, we recalculated the poverty rate after constructing a counterfactual measure of earnings for coresiding single mothers using the average employment hours of lone mothers and the observed wage rates for coresiding single mothers. This admittedly crude sensitivity test suggests that endogeneity of living arrangements and earnings (via work hours) is of limited importance. Indeed, the average work hours of lone mothers are very similar to those of their counterparts coresiding with parents, suggesting that single mothers with lower earnings capacity are more likely to coreside with parents.

Discussion

Single mothers are economically disadvantaged in all countries, but especially so in countries where public income support for families is more limited. Because a weak public safety net is often accompanied by strong traditions of family-provided support, a fuller understanding of the economic well-being of single mothers should account for the sharing of resources via intergenerational coresidence. Recent research on single mothers in the United States emphasizes the importance of income sharing, economies of scale, and shared housing (Haider and McGarry 2006; Magnuson and Smeeding 2005; Mutchler and Baker 2009), but has not explicitly considered the extent to which official poverty figures based on lone-mother households may overstate the degree of economic disadvantage among single mothers. In this paper, we have demonstrated that the high poverty rate for single mothers in Japan overstates poverty among single mothers by as much as 12–20 percent as a result of not including the roughly 30 percent of single mothers who coreside with parents.

This is an important contribution for two reasons. First, it provides an empirical assessment of the extent to which family support limits economic deprivation among single mothers in a country where the prevalence of single-mother families has risen sharply, public policies provide little income support to families in general and single mothers in particular, and where public and private expectations of family support (especially via coresidence) have a long history. Family support for single mothers is thus one more, current example of intergenerational coresidence as a strategic family response to the impact of rapid social and economic change (increasing marital instability, in this case). Routine calculation and presentation of alternative poverty measures reflecting this intrafamilial support would facilitate comparisons of economic deprivation of single mothers across countries in which the prevalence of intergenerational coresidence differs significantly.

Second, it demonstrates the limits of family-based support for economically vulnerable groups. We expected that single mothers coresiding with parents would be less likely to be in poverty than those living alone, but the difference between these two groups was surprisingly small. The fact that one-third of single mothers living with parents fall below the poverty line is evidence that, in many cases, the parents of single mothers are not financially capable of providing significant support. As noted above, our auxiliary analyses demonstrated that 20 percent of the parents in these intergenerational households would be in poverty even if not coresiding with their daughter and grandchildren, that another 19 percent were close enough to poverty that the addition of the daughter’s family pushed them into poverty, and that 8 percent were actually pulled out of poverty by the addition of their coresident daughter’s income.

We also posited that the rise in single-parent families might be offset by a corresponding increase in intergenerational coresidence, but found no evidence of such a change. The proportion of single mothers coresiding with parents remained at roughly .30 throughout the 20-year period we examined. There are several possible reasons for this relatively stable proportion of single mothers coresiding with parents. For example, distributions of geographic distance between generations or the quality of intergenerational relationships may effectively cap the prevalence of coresidential living arrangements. It is also possible that the characteristics of both single mothers and their parents have changed in ways that make coresidence less desirable. Such changes might include some improvement in the economic opportunities available to single mothers or declining economic well-being of the (grand)parental generation due to the prolonged recession. Unfortunately, these speculative interpretations cannot be evaluated without information on the characteristics of parents who do not coreside with their single-mother daughters. Taken as a whole, these figures suggest that the intergenerational transmission of poverty, the intergenerational transmission of divorce, and the concentration of divorce and single parenthood among women from the most disadvantaged backgrounds are all important issues for additional research on poverty in Japan.

Another important contribution of this study is our demonstration of the link between growth in single-mother families and increase in the overall poverty rate. Growing inequality and poverty is a major social and political issue in Japan (Tachibanaki 2006), and a good deal of attention has been paid to the particularly high rates of poverty among single mothers and their children. Nevertheless, efforts to explicitly link the growth in single-parent families to rising inequality and increasing poverty rates have been limited. Instead, attention has been directed primarily at the role of population aging (which has increased the prevalence of poor elderly households) and labor-market changes (including relatively high unemployment and stagnating wages, especially at younger ages). Our results show that the overall poverty rate (among mothers) in 2007 was 27 percent higher than in 1986, and that all of this difference can be explained by the higher prevalence of single mothers in 2007. This highlights the importance of rapid family change for understanding trends in inequality and poverty in countries where public policies provide limited income support for disadvantaged families.

It also points to the importance of future trends in divorce and non-marital childbearing. If non-marital childbearing increases in Japan, as it has in other low-fertility, low-marriage societies, further growth in the prevalence of single-mother families could have potentially important implications for overall rates of poverty and economic inequality. The likelihood of such change is unclear, however. On one hand, the continued strength of social sanctions against non-marital childbearing and barriers to women’s economic independence suggest little reason to expect a weakening of the close link between marriage and child-bearing (Jones 2007). On the other hand, projected increases in the proportion who never marry, the prevalence of non-marital cohabitation and premarital conception, increased social exposure to divorced single mothers, and a wide array of policy efforts to support work-family balance are all conditions conducive to growth in non-marital childbearing (Raymo and Iwasawa 2008; Raymo, Iwasawa, and Bumpass 2009; Rindfuss et al. 2004).

Data limitations precluded us from focusing on educational differences in single motherhood, living arrangements, and poverty, but it is clear that divorce and single parenthood are concentrated among women with lower levels of educational attainment in Japan (Raymo, Fukuda, and Iwasawa 2013). Our results are thus consistent with theoretical emphases on the role of growing differentials in family behavior and “diverging destinies” of women and children at different ends of the socioeconomic spectrum. Some sources of data suggest that coresidence with parents is positively associated with the educational attainment of single mothers in Japan (authors’ tabulation of data from the Luxembourg Income Study), while other sources suggest that educational differences are minimal (Raymo and Zhou 2012). As new data become available, subsequent research should examine educational differences in poverty among single mothers and assess the extent to which income sharing via coresidence ameliorates or exacerbates these differences.

The third contribution of this study is our use of counterfactual calculations to quantify the relative importance of earnings, public transfers, and income sharing via coresidence in shaping the economic well-being of single mothers. As in the United States, recent policy shifts in Japan have reduced the already limited levels of public income support for single mothers while supporting economic independence through employment. The vast majority of single mothers (close to 90 percent) are in the labor force, and the fact that 94 percent of those who are living alone would be in poverty if their earnings were counterfactually eliminated clearly demonstrates that earnings are the most important source of income for lone mothers and their children. The fact that 61 percent of these women are living in poverty despite their high rates of labor-force participation presumably reflects the limited earnings capacity of the women who become single mothers, the relatively low-paying, non-standard jobs available to them, and the difficulty of balancing full-time work and parenting.

For women living with parents, it is clear that shared income via coresidence is the most important factor in limiting poverty. The fact that the poverty rate calculated by counterfactually removing these women from the parental home is higher than the observed poverty rate for lone mothers highlights the importance of selection into coresidence. Using the limited information available in the CSLCJ, we confirmed that that this finding does not reflect shorter work hours among coresiding single mothers, and efforts to understand the factors associated with the decision to coreside with parents is another important task for subsequent research. Age may be a particularly important factor—auxiliary analyses show that single mothers coresiding with parents are somewhat younger than their counterparts living alone (mean ages of 37.0 and 39.7, respectively), and that the economic benefits of coresidence are more pronounced for younger mothers (tables available upon request).

We have also shown that conclusions regarding the importance of shared income via intergenerational coresidence are sensitive to assumptions regarding the nature of income pooling and sharing within the household. In the absence of any empirical evidence on the nature of sharing, we have followed the standard practice of assuming income pooling and full sharing, but we have also shown that the poverty-mitigating effects of coresidence are much less pronounced if one assumes that only half of coresident parents’ income is shared with single mothers. Efforts to collect the data required to ascertain the degree of intra-household income sharing, both in the Japanese context and cross-nationally, would be of substantial value. Without such information, consensus regarding the use of an alternative poverty measure for single mothers that accounts for coresidence is unlikely.

Despite the limitations imposed by available data, our findings offer important new insights into the role of intergenerational coresidence as a strategic family response to the implications of major changes in family behavior and family structure. This evidence from Japan builds upon a growing body of research in the United States that emphasizes the importance of “doubling up” in settings where public income support for single mothers is limited, where public policy increasingly emphasizes economic independence through employment, and where the earnings potential of many single mothers is limited. At a more general level, we have shown that official poverty statistics based on household data overstate the degree of economic disadvantage among single mothers in Japan, and presumably in other countries, where intergenerational coresidence is common. At the same time, the degree of this overstatement appears to be limited by the precarious economic position of the (grand)parents with whom single mothers coreside. This points to the importance of extending the focus of this study to consider both the role of single parenthood in the intergenerational transmission of economic disadvantage and the implications of single parenthood and “doubling up” not only for the single mothers themselves, but also for their parents.

We hope that future research will replicate and extend our analyses by using data from the United States and other countries. Assuming that broad trends in the decoupling of marriage and fertility and high rates of union dissolution contribute to growth in single-parent families beyond the wealthy OECD countries, efforts to understand the well-being of single mothers (and their children) will require attention to the role of private support via coresidence. Attention to intergenerational coresidence will not only enhance our ability to make effective cross-national comparisons of poverty among single mothers, but also provide a potentially important source of theoretical insight. For example, frameworks for understanding the “diverging destinies” of children that result from the concentration of single motherhood at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum, the feminization of poverty resulting from gender differences in childcare obligations and employment opportunities among single parents, and the reproduction of disadvantage resulting from the intergenerational transmission of single parenthood would all benefit from attention to the role of coresidence in reducing poverty. Our work hints at the importance of these issues, and continued efforts to produce answers could significantly enhance our understanding of the ways in which patterns of family change, including the rise in single parenthood, and their relationships with poverty and inequality are shaped by social, economic, and policy context.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) (number 20223004) and Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research (number 25000001) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). Permission to use data from the Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions in Japan was granted under this project (permission number 1009–3). Raymo acknowledges support from the Center for Demography and Ecology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison (R24 HD047873).

About the Authors

Sawako Shirahase is professor of sociology at the University of Tokyo. Her main research interests include social stratification and demographic change with a cross-national perspective and comparative studies of welfare states from the analytical framework of gender and generation. She is the author of Social Inequality in Japan (2013, Routledge) and the editor of Demographic Change and Inequality in Japan (2011, the Trans Pacific Press).

James Raymo is professor of sociology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where he is also the current director of the Center for Demography and Ecology. Raymo’s research focuses on evaluating patterns and potential consequences of demographic changes associated with rapid population aging in Japan. He has published widely on key features of recent family change in Japan, including delayed marriage, extended coresidence with parents, and increases in premarital cohabitation, shotgun marriages, and divorce.

Contributor Information

Sawako Shirahase, University of Tokyo.

James M. Raymo, University of Wisconsin–Madison

References

- Abe Aya K. 2003. “Low-Income People in Social Security Systems in Japan.” Japanese Journal of Social Security Policy 2(2):59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Abe Aya K. 2008. Children’s Poverty: A Study of Inequality in Japan. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten; In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Abe Aya, and Oishi Akiko. 2005. “Social Security and the Economic Circumstances of Single-Mother Households” In Social Security and Households with Children, edited by National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, 143–61. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press; In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Abebe Tatek, and Aase Asbjorn. 2007. “Children, AIDS, and the Politics of Orphan Care in Ethiopia: The Extended Family Revisited.” Social Science & Medicine 64(10):2058–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akaishi Chieko. 2011. “Single Mothers” In Transforming Japan: How Feminism and Diversity Are Making a Difference, edited by Kumiko Fujimura-Fanselow, 121–30. New York: Feminist Press at the City University of New York. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman Kurt J. 2000. “The Effect of Work and Welfare on Living Conditions in Single-Parent Households.” Working Paper No. 46. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Baydar Nazli, and Brooks-Gunn Jeanne. 1998. “Profiles of Grandmothers Who Help Care for Their Grandchildren in the United States.” Family Relations 47(4):385–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson Vern L. 2001. “Beyond the Nuclear Family: The Increasing Importance of Multigenerational Bonds.” Journal of Marriage and Family 63(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Blank Rebecca M. 2006. “What Did the 1990s Welfare Reforms Accomplish?” In Poverty, the Distribution of Income and Public Policy, edited by Auerbach Alan J., Card David, and Quigley John M., 33–79. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Blank Rebecca M. 2011. Changing Inequality. Vol. 8 Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brinton Mary C. 2001. “Married Women’s Labor in East Asian Economies” In Women’s Working Lives in East Asia, edited by Brinton Mary C., 1–37. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. Brian, and Lichter Daniel T.. 2004. “Poverty, Welfare, and the Livelihood Strategies of Nonmetropolitan Single Mothers.” Rural Sociology 69(2):282–301. [Google Scholar]

- Cancian Maria, and Reed Deborah. 2009. “Family Structure, Childbearing, and Parental Employment: Implications for the Level and Trend in Poverty.” Focus 26(2):21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Casper Lynne M., and Bianchi Suzanne M.. 2002. Change and Continuity in the American Family. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Casper Lynne M., McLanahan Sara S., and Garfinkel Irwin. 1994. “The Gender-Poverty Gap: What We Can Learn from Other Countries.” American Sociological Review 59(4):594–605. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher Karen. 2002. “Single Motherhood, Employment, or Social Assistance: Why Are US Women Poorer Than Women in Other Affluent Nations?” Journal of Poverty 6(2):61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher Karen, England Paula, Smeeding Timothy M., and Phillips Katherin R.. 2012. “The Gender Gap in Poverty in Modern Nations: Single Motherhood, the Market, and the State.” Sociological Perspectives 45(3):219–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Zuanna Gianpiero, and Micheli Giuseppe A., eds. 2004. Strong Family and Low Fertility: A Paradox? New Perspectives in Interpreting Contemporary Family and Reproductive Behavior. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Edin Kathryn, and Lein Laura. 1997. “Work, Welfare, and Single Mothers’ Economic Survival Strategies.” American Sociological Review 62(2):253–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ellwood David T., and Jencks Christopher. 2004. “The Uneven Spread of Single-Parent Families: What Do We Know? Where Do We Look for Answers?” In Social Inequality, edited by Neckerman Kathryn, 3–78. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Ezawa Aya, and Fujiwara Chisa. 2005. “Lone Mothers and Welfare-to-Work Policies in Japan and the United States: Towards an Alternative Perspective.” Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare 32(4):41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara Chisa. 2007. “Stratification among Single-Mother Families.” Journal of Research on Household Economics (73):10–20. In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg Frank F., Brooks-Gunn Jeanne, and Morgan S. Philip. 1987. Adolescent Mothers in Later Life. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman Roger, and Peng Ito. 1996. “The East Asian Welfare States: Peripatetic Learning, Adaptive Change, and Nation-Building” In Welfare States in Transition: National Adaptations in Global Economies, edited by Esping-Andersen Gosta, 192–224. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon Rachel A. 1999. “Multigenerational Coresidence and Welfare Policy.” Journal of Community Psychology 27(2):525–49. [Google Scholar]

- Haider Steven J., and McGarry Kathleen. 2006. “Recent Trends in Income Sharing among the Poor” In Working and Poor: How Economic and Policy Changes Are Affecting Low-Wage Workers, edited by Blank Rebecca, Danziger Sheldon, and Schoeni Robert, 205–32. New York: Russell Sage Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harada Sumitaka. 1988. “Family in the Japanese Welfare State” In Welfare State in Transition. Institute of Social Sciences, edited by the University of Tokyo, 303–92. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press; In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Iceland John. 2003. “Why Poverty Remains High: The Role of Income Growth, Economic Inequality, and Changes in Family Structure, 1949–1999.” Demography 40(3):499–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata Masami. 2007. Poverty in Contemporary Society: The Working Poor, the Homeless, and Public Assistance. Tokyo: Chikuma-shobo; In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training. 2012. Report on the Employment and Life Circumstances of Households with Children. Survey Series No. 95. Tokyo: Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training; In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Gavin W. 2007. “Delayed Marriage and Very Low Fertility in Pacific Asia.” Population and Development Review 33(3):453–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kaestner Robert, Korenman Sanders, and O’Neill June. 2003. “Has Welfare Reform Changed Teenage Behaviors?” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 22(2):225–48. [Google Scholar]

- Karoly Lynn A., and Burtless Gary. 1995. “Demographic Change, Rising Earnings Inequality, and the Distribution of Personal Well-Being, 1959–1989.” Demography 32(3):379–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter Daniel T., and Crowley Martha L.. 2004. “Welfare Reform and Child Poverty: Effects of Maternal Employment, Marriage, and Cohabitation.” Social Science Research 33(3):385–408. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter Daniel T., Graefe Deborah R., and Brown J. Brian. 2003. “Is Marriage a Panacea? Union Formation among Economically Disadvantaged Unwed Mothers.” Social Problems 50(1):60–86. [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson Katherine, and Smeeding Timothy. 2005. “Earnings, Transfers, and Living Arrangements in Low-Income Families: Who Pays the Bills?” Paper presented at the National Poverty Center Conference on Mixed Methods Research on Economic Conditions, Public Policy, and Family and Child Well-Being, Ann Arbor, MI. [Google Scholar]

- Martin Molly A. 2006. “Family Structure and Income Inequality in Families with Children, 1976 to 2000.” Demography 43(3):421–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan Sara. 2004. “Diverging Destinies: How Children Are Faring Under the Second Demographic Transition.” Demography 41(4):607–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2012. Report on the 2011 National Survey of Single-mother Households. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; In Japanese. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kodomo/kodomo_kosodate/boshi-katei/boshi-setai_h23/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Misra Joya, Moller Stephanie, Strader Eiko, and Wemlinger Elizabeth. 2012. “Family Policies, Employment and Poverty among Partnered and Single Mothers.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 30(1):113–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell Barbara A. 2006. The Boomerang Age: Transitions to Adulthood in Families. New Brunswick, NJ: Aldine Transaction. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S. Philip, and Hirosima Kiyosi. 1983. “The Persistence of Extended Family Residence in Japan: Anachronism or Alternative Strategy?” American Sociological Review 48(2):269–81. [Google Scholar]

- Mutchler Jan E., and Baker Lindsey A.. 2009. “The Implications of Grandparent Coresidence for Economic Hardship among Children in Mother-Only Families.” Journal of Family Issues 30(11):1576–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. 2012. Latest Demographic Statistics. Tokyo: National Institute of Population and Social Security Research; In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols-Casebolt Ann, and Krysik Judy. 1997. “The Economic Well-Being of Never- and Ever-Married Single-Mother Families.” Journal of Social Service Research 23(1):19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nishi Fumihiko. 2012. “Characteristics of Single Mothers in 2010.” http://www.stat.go.jp/training/2kenkyu/pdf/zuhyou/single4.pdf. In Japanese.

- OECD (the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2011. Social Indicators. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa Naohiro, and Retherford Robert D.. 1997. “Shifting Costs of Caring for the Elderly Back to Families in Japan: Will It Work?” Population and Development Review 23(1):59–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ohtake Fumio. 2005. Inequality in Japan: The Illusion and the Future of Unequal Society Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Shimbunsha; In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Ono Hiroshi. 2010. “The Socioeconomic Status of Women and Children in Japan: Comparisons with the USA.” International Journal of Law, Policy, and the Family 24(2):151–76. [Google Scholar]

- Osawa Machiko. 2006. Toward a Work-Life Balance Society. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten; In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Raymo James M., Fukuda Setsuya, and Iwasawa Miho. 2013. “Educational Differences in Divorce in Japan.” Demographic Research 28(6):177–206. [Google Scholar]

- Raymo James M., and Iwasawa Miho. 2008. “Bridal Pregnancy and Spouse Pairing Patterns in Japan.” Journal of Marriage and Family 70(4):847–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymo James M., Iwasawa Miho, and Bumpass Larry. 2004. “Marital Dissolution in Japan: Recent Trends and Patterns.” Demographic Research 11(14):395–419. [Google Scholar]

- Raymo James M., Iwasawa Miho, and Bumpass Larry. 2009. “Cohabitation and Family Formation in Japan.” Demography 46(4):785–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymo James M., and Zhou Yanfei. 2012. “Coresidence with Parents and the Well-Being of Single Mothers in Japan.” Population Research and Policy Review 31(5):727–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss Ronald R., Choe Minja K., Bumpass Larry L., and Tsuya Noriko O.. 2004. “Social Networks and Family Change in Japan.” American Sociological Review 69(6):838–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sato Toshiki. 2000. Unequal Japan. Tokyo: Chuo Koron Shinsha; In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Shirahase Sawako. 2013. Social Inequality in Japan. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Short Kathleen, and Smeeding Timothy M.. 2005. “Consumer Units, Households, and Sharing: A View from the Survey of Income and Program Participation SIPP.” Working Paper, US Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Sigle-Rushton Wendy, and McLanahan Sara. 2002. “The Living Arrangements of New Unmarried Mothers.” Demography 39(3):415–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack Carol B. 1974. All Our Kin: Strategies for Survival in Black Communities. New York: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Tachibanaki Toshiaki. 1998. Economic Inequality in Japan. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten; In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Tachibanaki Toshiaki. 2006. “Inequality and Poverty in Japan.” Japanese Economic Review 57(1):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Tamiya Yuko, and Shikata Masato. 2007. “Employment and Housework in Single-Mother Households: Evidence from a Cross-National Comparison of Time Use.” Social Security Research 43(3):219–31. In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Teitler Julien O., Reichman Nancy E., and Nepomnyaschy Lenna. 2004. “Sources of Support, Child Care, and Hardship among Unwed Mothers, 1999–2001.” Social Service Review 78(1):125–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tokoro Michihiko. 2003. “Social Policy and Lone Parenthood in Japan: A Workfare Tradition.” Japanese Journal of Social Security Policy 2(2):45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Tsumura Atsuko. 2002. “International Comparison of Family Policy” In Support for Child-Rearing in Low-Fertility Societies, edited by National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, 19–46. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press; In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Western Bruce, Bloome Deirdre, and Percheski Christine. 2008. “Inequality among American Families with Children, 1975 to 2005.” American Sociological Review 73(6):903–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yuzawa Naomi, and Fujiwara Chisa. 2009. “Household Structure and Individual Characteristics of Households Receiving Public Assistance.” Japanese Journal of Social Services (50):16–28. In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Yuzawa Naomi, and Fujiwara Chisa. 2010. “Initiation and Termination of Public Assistance Receipt among Single-Mother Households.” Journal of Ohara Institute for Social Research 620:49–63. In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Yanfei. 2008. “Single Mothers Today: Increasing Numbers, Employment Rates, and Income” In Research on Employment Support for Single Mothers, JILPT Research Report No. 101, edited by Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, 26–38. Tokyo: Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training; In Japanese. [Google Scholar]