Abstract

Facial asymmetry, following early childhood condylar trauma, is a common complaint among patients who seek surgical treatment. G.D.M., a 27-year-old male patient, sought professional help to correct his cosmetic flaw, caused by a condylar fracture when he was 8-years-old. After the proper orthodontic treatment, he underwent a double jaw orthognathic surgery and, 9 months later, a second one to correct the remaining asymmetry. Two years after this second procedure, the patient is still under surveillance and has no complaints.

Keywords: facial asymmetry, laterognathia, orthognathic surgery, condylar fracture

Bailey et al 1 reported that as many as 35% of patients who sought orthognathic evaluation exhibited asymmetry of the lower third of the face. 1 2 Severe facial asymmetry can be caused by several factors, including genetic imperfections and environmental influences. 3 4 Among the latter, the mandibular condyle is one of the most common sites of injury of the facial skeleton, but it is also the most overlooked and least diagnosed trauma site in the head and neck region. 5 6 The proposed reason for the development of asymmetries is an interference with growth, resulting either from injury to the condylar cartilage or from altered function. 7 Destruction of the condyle in adults is said to result in more subtle asymmetries, as growth has ceased and the mandible has reached its normal size and form. 7 Confronted with this type of malocclusion, the treatment options have been functional therapy, occlusal equilibration, extraction of interfering teeth, prosthodontics, orthodontics, orthognathic surgery, or a combination of these. 8 9 Normally, the great majority of condylar process fractures are treated with closed reduction. 10 Facial asymmetry due to jaw growth disturbances almost always requires corrective orthognathic surgery. 10 11 12 13 14 15

The purpose of this article is to report an uncommon two-phase surgical treatment of a 27-year-old patient with laterognathia who had a noticeable facial deformity caused by a condylar fracture in his early childhood, which led to a condylar neoformation. When researching the risk of undetected early-age condylar fractures, the PubMed database was used.

Case Report

G.D.M., a 27-year-old male patient who had a misdiagnosed condylar fracture at the age of 8 years, sought professional help complaining about his visible facial asymmetry ( Figs. 1 and 2 ). Clinical examination revealed a limitation of mouth opening (around 28 mm), occlusal plane rotation, and a Class I occlusion on both sides, associated with laterognathia ( Figs. 3 4 5 ). The patient reported no complaints concerning his mouth opening ability, although he had some difficulty lateralizing the mandible toward the right (where the condyle was normal). Laterality to the left side was preserved. Cone beam computed tomographic (CBCT) scans demonstrated facial asymmetry ( Fig. 6 ), a deformed left temporomandibular joint (TMJ; Fig. 7 ), hyperplasia of the left coronoid process, and a shortening of the left mandibular ramus ( Fig. 8 ). The preoperative test results were within the normal limits and the patient was classified as ASA I (American Society of Anesthesiologists). As mouth opening and laterality were preserved, the deformed TMJ could not be labeled as a pseudoarthrosis.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative frontal view.

Fig. 2.

Preoperative facial profile view.

Fig. 3.

Preoperative intraoral right view.

Fig. 4.

Preoperative intraoral frontal view.

Fig. 5.

Preoperative intraoral left view.

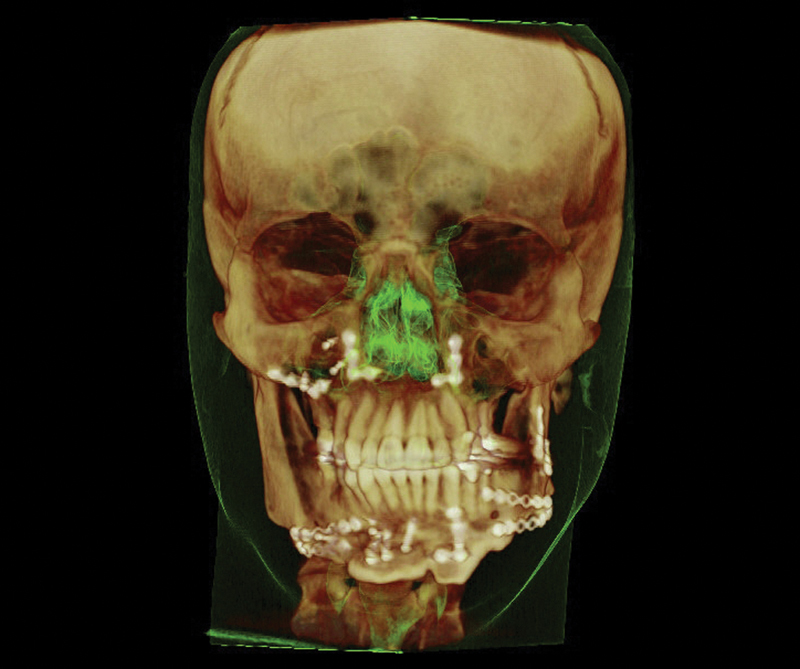

Fig. 6.

Preoperative 3D reconstruction cone beam computed tomographic scan, frontal view.

Fig. 7.

Preoperative coronal cone beam computed tomographic scan showing the left deformed condyle.

Fig. 8.

Preoperative panoramic X-ray.

After a proper 2-year orthodontic treatment, surgical planning was made using the CBCT scans uploaded into the Dolphin 3D software (Dolphin Imaging and Management Systems, Chatsworth, CA), with the aid of the Arnett facial analysis. 16 Regarding surgical planning, the patient did not accept the option of being submitted to a bone distraction, and was informed of the possibility of having more than one orthognathic procedure done. As the condyles were functioning well (except for the lateral shift to the shortened side) and the patient was symptom free, no TMJ prostheses were recommended.

Initially, a surgical advancement of the maxilla, mandible, and symphysis along with maxillary rotation and impaction (to correct the midline of the laterally deviated lower third) were planned. However, due to the large discrepancy in the mandibular angle, it was observed that a total correction would not be possible, as it would lead to the formation of a wide gap, which could cause a pseudoarthrosis in the sagittal split osteotomy (SSO). Thus, the priority was to correct the maxillomandibular deviation, the anteroposterior and vertical discrepancies, while the corrections of the ramus and the mandibular angle were left for a later surgical intervention, after the proper bone healing at the primary osteotomies.

The first surgery started with the osteotomy of the maxilla, performing the downfracture and compensating the cant deviation, impacting and leveling it with the facial midline as much as possible. Then, a bilateral SSO was made and the mandible advanced as far as possible, to maintain bone contact on the left side, achieving initial asymmetry correction. Additionally, a genioplasty was done, advancing the chin according to the facial planning. The procedure changed the occlusal plane by approximately 12 mm superiorly on the right side ( Figs. 9 10 11 12 ).

Fig. 9.

Postoperative 3D cone beam computed tomographic scan, after the first procedure.

Fig. 10.

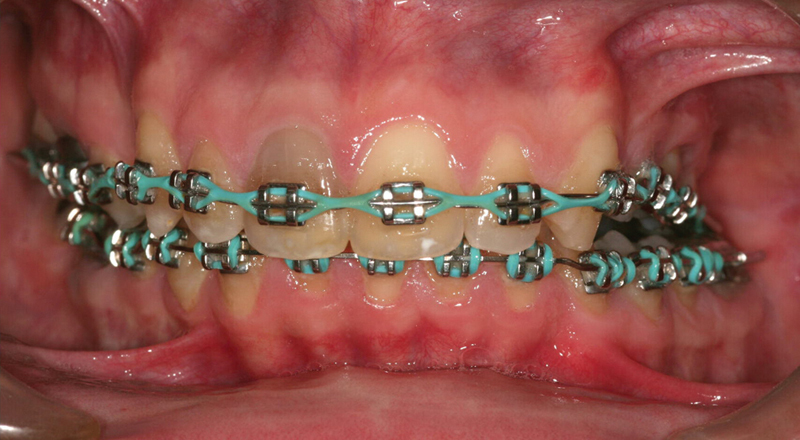

Intermediary intraoral right view.

Fig. 11.

Intermediary intraoral frontal view.

Fig. 12.

Intermediary intraoral left view.

Nine months later, a second procedure started with the osteotomies of the mandible, compensating the cant, the yaw, and the facial midline. Furthermore, a minor correction was done in the maxilla to achieve a final Class I occlusion. Another genioplasty was necessary, in a segmented way, to correct the residual transversal discrepancy of the symphysis. A Medpor (Porex Surgical, Inc., College Park, GA) polymer prosthesis was placed on the right zygomatic bone, where the soft tissue was discrepant.

Owing to the telescopic effect and its resultant stability following maxillary repositioning, no plate or positional screws were placed in the left zygomatic buttress, in any of the two procedures. Only intermediary splints were used in both surgeries.

The patient recovered well in both postoperative periods, and his orthodontic finalization took 1 more year. His last follow-up visit was 2 years after the second surgery ( Figs. 13 and 14 ). The postoperative CT scan performed 2 years later ( Fig. 15 ) and panoramic X-ray ( Fig. 16 ) confirmed an adequate segment consolidation and alignment. The patient has no functional or aesthetic complaints, although his mouth opening is still limited (around 31 mm; Figs. 17 18 19 ). The neurosensory deficit of the inferior alveolar nerves declined over time, but there is still some numbness.

Fig. 13.

Postoperative frontal view after 2 years.

Fig. 14.

Postoperative facial profile view after 2 years.

Fig. 15.

Postoperative 3D cone beam computed tomographic scan, frontal view after 2 years.

Fig. 16.

Postoperative panoramic X-ray after 2 years.

Fig. 17.

Final intraoral right view.

Fig. 18.

Final intraoral frontal view.

Fig. 19.

Final intraoral left view.

Discussion

A laterally deviated mandible is a condition with many possible causes. In some cases, the cause is very clear, for example, an overt trauma or the existence of other pathognomonic features in a syndrome. Often, however, a simple explanation for such asymmetry is not found and its cause needs to be sought among various conditions, such as those described in Table 1 . If the mandibular ramus is short and the condyle is distorted, but the ears and adjacent soft tissues are normal, it is probable that the asymmetry is due to early childhood fractures left untreated, causing condylar malformation, even if the previous diagnosis of these fractures or the specific trauma episodes were not reported. 17 This is what probably happened in this case.

Table 1. Possible causes of laterognathism.

| Categories | ||

|---|---|---|

| Glenoid fossa malposition due to modification in the cranial base | Condylar abnormalities | |

| Muscular torticollis (especially in the mild form) 2 | X | |

| Previous subcondylar or condylar fractures 2 14 17 | X | |

| Delayed fracture treatment or unfavorable outcome from surgery 8 | X | |

| Forceps birth trauma 30 | X | |

| Condylar hyperplasia 2 | X | |

| Condylar hypoplasia 2 | X | |

| Juvenile condylar arthritis 2 | X | |

| Hemifacial microssomia 2 17 | X | |

| Deformational posterior plagiocephaly 2 | X | |

| Unilateral coronal craniosynostosis 2 | X | |

Usually, the protected environment that surrounds infants and preschool children partly accounts for their relative immunity to injuries. Falls 2 15 and vehicular accidents 2 are a commonplace. Since it is more difficult to clinically examine a toddler, a radiological study is harder to perform in an uncooperative child and the examiner may be distracted from a condylar fracture by more life-threatening head and neck injuries that commonly accompany mandibular trauma in children. 15 18 19 Often, parents do not consult a physician for what appears to be a laceration or small amount of soft-tissue swelling. 2 5 The young child does not have the verbal ability to complain of mandibular pain; instead, the child may have nonspecific irritability and anorexia, which are attributed to some other cause. 15 18 19 Therefore, in cases involving blunt trauma to the chin or mandible, it is important to suspect a possible injury to the condyle since the result of a missed fracture may be serious. 15 18 19

Condylar and subcondylar fractures (excluding the nasal bone) are the most common facial fractures in the pediatric population. 2 14 The occurrence of posttraumatic malocclusion is reported to range from 1.4% to 13%. 8 10 11 20 21

Conservative nonsurgical treatments of condylar fractures in children consist of any or a combination of the following: dietary restriction, maxillomandibular fixation (MMF), guiding elastics, removable functional orthopedic appliance, and acrylic resin split. 2 5 22 The splint is an acrylic orthopedic functional device worn full time, and which covers the occlusal surfaces of the teeth in the mandible. Its posterior height is gradually increased in the arthritic side on a weekly basis. 23 24 According to Stoustrup et al, 23 this distraction splint has become a vital orthopedic modality in the treatment of patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis in one or both TMJ. In a conservative treatment, the functional rehabilitation relies on the remodeling capacity of the joint.

Laterally deviated mandibles can pose problems to patients, such as those mentioned in Table 2 .

Table 2. Problems related to laterally deviated mandibles.

| Cosmetic appearance from obvious facial asymmetry 2 5 |

| Anterior open bite 12 |

| Distinct difference between centric occlusion and centric relation 12 |

| Dorsal dislocation of the mandible 12 |

| Shortening of the posterior and lengthening of the anterior facial height 11 12 |

| Altered occlusion 2 5 11 |

| Alterations in the jaw range of motion 2 5 |

| Masticatory muscles hipertonia 11 |

| Inability to generate sufficient bite force 11 |

| Constellation of TMJ disorder symptoms (such as pain and clicking) 2 5 11 |

The correct diagnosis helps decide if orthognathic correction is needed, including timing, technique, and detailed preparation and planning. In addition, it may prevent or minimize lateral mandibular relapse after surgical correction. 2 For example, if there is no occlusal cant and the mandibular movement to be corrected is 2 mm or less, this asymmetry is considered too small to be concerned about. However, surgeons typically want to correct the bimaxillary central incisor midline, as this is often critiqued postoperatively. 2 25

Controversy exists regarding when unilateral or bilateral SSO should be performed. Thus, in cases with asymmetric posttraumatic malocclusion caused by a condylar process fracture, the only surgical option is an osteotomy of the affected side of the mandible. 8 11 12 26 Other authors postulated that this should be made on both sides. 8 12 27 We believe that a sole unilateral SSO should only be executed in short-term sequelae (few months), while an older deformity should be treated with bimaxillary surgery.

Regarding the maxillary correction, an open bite can be considered for either an entirely posttraumatic situation or an acquired dentofacial deformity. 8 10 The first case calls for restoration of ramus height; the latter advocates closure of the anterior open bite with (bi)maxillary surgery. 8 10

Besides condylar malformation, patients can present with different TMJ problems such as pain, limited and asymmetric mandibular movement, and noises in the TMJ after conservative treatment of condylar fractures. 12 In a nonfractured TMJ, pain may possibly arise from functional overload (“condylar postfracture syndrome”). 12 Nevertheless, our patient reported no TMJ dysfunction on either side.

Treatment success, however, depends on the severity of the damaged tissue. If condylar translation is restricted, surgical release of the ankylosis or the scar is necessary prior to the orthopedic treatment; otherwise the condyle will not respond to it. 3 28 In this case, the slightly limited mouth opening did not compromise the surgical planning nor did it justify another invasive treatment, especially in the TMJ region. If the facial asymmetry develops progressively during orthopedic treatment, surgical reconstruction of the TMJ with a costochondral graft or the remaining ramus tissue might be considered. 3 29 If the patient has completed growing, skeletal deformities are corrected with a combined surgical–orthodontic treatment or a camouflage orthodontic treatment. 3 29

In agreement with Choi et al 5 and Motta et al, 30 the CT scan was paramount for the patient's surgical planning, as it showed the exact anteroposterior and lateromedial dimensions of the deformed TMJ, which were not evident in the panoramic X-ray.

Choi et al 5 and Hovinga et al 22 concluded that the nonsurgical treatment of dislocated condylar process fractures in children has satisfactory long-term outcome of jaw function, despite the high frequency of radiologically noted aberrations. Serious growth disturbances are rare, but cannot be predicted based on the type of fracture. Conservative treatment is not only more patient friendly but generally also gives very good results, no worse than that of open reduction. 22 Similarly, Becking et al 8 10 reported that the low prevalence of posttraumatic malocclusion and the good results of orthognathic surgery in correcting it, suggesting that prevention of malocclusion cannot be considered a strong argument for open reduction and fixation of condylar process fractures on a routine basis. Moreover, one might hypothesize that it is the ability of teeth to intrude that allows for the recovery of a good occlusal relationship after a fracture. Therefore, tooth intrusion and the resultant asymmetry should be regarded as a favorable biological adaptation. 7 Finally, the number of patients requiring orthodontic intervention following mandibular fracture was similar in all four age groups of the study of Demianczuk et al, 15 ranging from 28% to 35% (average: 30.25%). This is similar to the normal (nonfracture) frequency of orthodontic intervention in North America. 15 31 Thus, fracture of the mandible in children does not lead to an increased incidence of orthodontic intervention. 15

Conclusion

A proper clinical test following a trauma is paramount to avoid late mandibular asymmetry. When properly instituted, the usual nonsurgical treatment in children provides satisfactory results. Nevertheless, the incidence of posttraumatic malocclusion apparently does not increase the amount of orthodontic intervention. Once the laterognathia is installed and the patient is fully grown, proper orthodontic treatment followed by combined orthognathic surgery is the treatment of choice. In some cases, depending on the severity of the case, more than one surgical procedure may be necessary to correct the asymmetry.

References

- 1.Bailey L J, Haltiwanger L H, Blakey G H, Proffit W R. Who seeks surgical-orthodontic treatment: a current review. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 2001;16(04):280–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawamoto H K, Kim S S, Jarrahy R, Bradley J P. Differential diagnosis of the idiopathic laterally deviated mandible. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(05):1599–1609. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181babc1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamashiro T, Okada T, Takada K. Case report: facial asymmetry and early condylar fracture. Angle Orthod. 1998;68(01):85–90. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1998)068<0085:CRFAAE>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bishara S E, Burkey P S, Kharouf J G. Dental and facial asymmetries: a review. Angle Orthod. 1994;64(02):89–98. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1994)064<0089:DAFAAR>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi J, Oh N, Kim I K. A follow-up study of condyle fracture in children. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34(08):851–858. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dimitroulis G. Condylar injuries in growing patients. Aust Dent J. 1997;42(06):367–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1997.tb06079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis E, III, Throckmorton G.Facial symmetry after closed and open treatment of fractures of the mandibular condylar process J Oral Maxillofac Surg 20005807719–728., discussion 729–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becking A G, Zijderveld S A, Tuinzing D B. The surgical management of post-traumatic malocclusion. Clin Plast Surg. 2007;34(03):e37–e43. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahlström L, Kahnberg K E, Lindahl L. 15 years follow-up on condylar fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;18(01):18–23. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(89)80009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becking A G, Zijderveld S A, Tuinzing D B.Management of posttraumatic malocclusion caused by condylar process fractures J Oral Maxillofac Surg 199856121370–1374., discussion 1374–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubens B C, Stoelinga P J, Weaver T J, Blijdorp P A. Management of malunited mandibular condylar fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;19(01):22–25. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80563-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spitzer W J, Vanderborght G, Dumbach J. Surgical management of mandibular malposition after malunited condylar fractures in adults. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1997;25(02):91–96. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(97)80051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smets L M, Van Damme P A, Stoelinga P J. Non-surgical treatment of condylar fractures in adults: a retrospective analysis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2003;31(03):162–167. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(03)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Souza M, Oeltjen J C, Panthaki Z J, Thaller S R. Posttraumatic mandibular deformities. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18(04):912–916. doi: 10.1097/scs.0b013e3180684377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demianczuk A N, Verchere C, Phillips J H. The effect on facial growth of pediatric mandibular fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 1999;10(04):323–328. doi: 10.1097/00001665-199907000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnett G W, Jelic J S, Kim J et al. Soft tissue cephalometric analysis: diagnosis and treatment planning of dentofacial deformity. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;116(03):239–253. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(99)70234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proffit W R, Turvey T A. Asimetria dentofacial. Tratamento Contemporâneo de Deformidades Dentofaciais. In: Proffit W R, Turvey T A, Sarver D M, editors. Porto Alegre, Brazil: Artmed; 2005. pp. 609–680. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leake D, Doykos J, III, Habal M B, Murray J E. Long-term follow-up of fractures of the mandibular condyle in children. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1971;47(02):127–131. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197102000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaban L B, Mulliken J B, Murray J E. Facial fractures in children: an analysis of 122 fractures in 109 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;59(01):15–20. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197701000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silvennoinen U, Iizuka T, Oikarinen K, Lindqvist C. Analysis of possible factors leading to problems after nonsurgical treatment of condylar fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52(08):793–799. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Amaratunga N A. Mouth opening after release of maxillomandibular fixation in fracture patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;45(05):383–385. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(87)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hovinga J, Boering G, Stegenga B. Long-term results of nonsurgical management of condylar fractures in children. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;28(06):429–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stoustrup P, Küseler A, Kristensen K D, Herlin T, Pedersen T K. Orthopaedic splint treatment can reduce mandibular asymmetry caused by unilateral temporomandibular involvement in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Eur J Orthod. 2013;35(02):191–198. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjr116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pedersen T K, Grønhøj J, Melsen B, Herlin T. Condylar condition and mandibular growth during early functional treatment of children with juvenile chronic arthritis. Eur J Orthod. 1995;17(05):385–394. doi: 10.1093/ejo/17.5.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ueki K, Hashiba Y, Marukawa K et al. Comparison of maxillary stability after Le Fort I osteotomy for occlusal cant correction surgery and maxillary advanced surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104(01):38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zachariades N, Mezitis M, Michelis A. Posttraumatic osteotomies of the jaws. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;22(06):328–331. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80659-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bloomquist D S. Mandibular body sagittal osteotomy in the correction of malunited edentulous mandibular fractures. J Maxillofac Surg. 1982;10(01):18–23. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(82)80006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Proffit W R, Vig K W, Turvey T A. Early fracture of the mandibular condyles: frequently an unsuspected cause of growth disturbances. Am J Orthod. 1980;78(01):1–24. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(80)90037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Proffit W R, White R P., Jr . St Louis, MO: Mosby; 1986. Surgical Orthodontic Treatment; pp. 483–549. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Motta A, Louro R S, Medeiros P J, Capelli J., Jr Orthodontic and surgical treatment of a patient with an ankylosed temporomandibular joint. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131(06):785–796. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wheeler T T, McGorray S P, Yurkiewicz L, Keeling S D, King G J. Orthodontic treatment demand and need in third and fourth grade schoolchildren. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1994;106(01):22–33. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(94)70017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]