Abstract

Sexual assault is a major public health concern and college women are four times more likely to experience sexual assault than any other group. We investigated whether sexting is a mechanism by which alcohol use increases risk for college women to be targeted for sexual assault. We hypothesized that sexting would mediate the relationship between problem drinking and sexual assault, such that drinking (T1=beginning fall semester) would contribute to increased sexting (T2=end fall semester), and in turn increase the risk of being targeted for sexual assault (T3=end spring semester). Results: Among 332 undergraduate women (M(SD)age=19.15(1.69), 76.9% Caucasian), sexting (T2) predicted sexual assault (T3; b=3.98, p=.05), controlling for baseline sexual assault (b=0.82, p<.01). Further, sexting (T2) mediated the relationship between problem drinking (T1) and sexual assault (T3) (b=0.04, CI[.004,.12]). Conclusion: Findings suggest that sexting is one mechanism through which drinking increases the risk of college women being targeted for sexual assault.

Sexual assault is a major public health concern and college women are four times more likely to experience sexual assault than any other group.1 Current estimates suggest one in five college women are victims of sexual assault.2 Sexual assault victims are at increased risk for re-victimization,3 as well as significant long-term psychological consequences4,5 and multiple health risk behaviors, including heavy drinking, eating disorders, and drug abuse.6–8 The goal of the current study was to examine whether sexting behavior is a mechanism by which alcohol use increases risk for college women being targeted for sexual assault.

The responsibility for sexual assault rests solely on the perpetrators. Within that context, it is valuable to understand risk processes for assault as comprehensively as possible. Two of the strongest predictors of sexual assault are having been previously assaulted 3,9 and substance use.10 There are many reasons that having been previously assaulted might increase one’s risk for experiencing further assault. For some women, certain post assault psychological symptoms, such as emotional distress and intrusive thoughts may inhibit one’s ability to perceive or response to potential risk dues or danger in situations that are similar to the previous assault (Messman-Moore et al., 2007).11 Additionally, for some victims, the experience of having been sexually assaulted predicts an increase in externalizing dysfunction, including substance use, which may increase risk and enhance one’s vulnerability for experiencing further assault.12 Furthermore, at least 50% of reported sexual assault cases among college students involve alcohol consumption by the victim, perpetrator, or both.13–14 Alcohol is thought to increase risk for sexual assault through multiple mechanisms: (1) alcohol is assumed to enhance sexual experiences and lower perpetrators’ inhibition;15–16 (2) women who are drinking are often misperceived by men and women as more sexually promiscuous and willing to engage in sex compared to non-drinking women;17–18 (3) some men report that it is acceptable to force sex on an intoxicated date;19–20 and (4) alcohol makes women less able to recognize, evade, and defend against sexual assault by reducing one’s cognitive capacity to acknowledge threats.21–23

Sexting, defined as the exchange of sexually charged content (picture or text) via mobile phone or social media,24 could be an important risk factor for sexual assault. Between 46.6%–80.3% of college students report that they have exchanged sexts,24–25 and sexting is viewed as a normative behavior, often used as a mechanism to “flirt” and initiate sexual activity.25–27 However, sexting is also associated with a range of risky sexual behaviors24 including unprotected sex, sex with multiple partners, alcohol-related sexual encounters, and sex with a new partner after sexting.25,28–31 College students who report frequent sexting also report more frequent and problematic alcohol use.28–31 It is possible that drinking could increase the likelihood of sending or exchanging a sext due to alcohol’s disinhibiting effects on judgment and decision making.13–14 For example, experimental studies have shown that those who are drinking or perceive they are drinking report stronger motives to make a sexual advance.32 We theorize that this phenomenon may be similar for sexting, such that those who are drinking may be more likely or inclined to sext due to similar mechanisms. In addition, drinking directly increases the chances of a sexual encounter (consensual or nonconsensual),15,33–34 and cross-sectional data document that sexting likely mediates the link between drinking and sexual hookups.30 We postulate that sexting might serve as a mechanism by which alcohol use increases risk for one being targeted for sexual assault.30 For example, a recipient of a sext message from a woman who is drinking may misinterpret the woman’s sext as a signal of sexual intent or consent given gender differences in how men and women interpret sexts.35 Because women who are drinking are often misperceived by others as more sexually promiscuous and willing to engage in sex and are more often targeted for sexual assault compared to non-drinking women,17 it is also possible that perpetrators may target a woman who is drinking – and therefore more vulnerable to assault – and exchanging sexts not only because she is drinking but also because she is perceived as interested in sex or even as having given consent via a sext message. Longitudinal work is needed to examine whether sexting mediates the predictive influence of alcohol use on subsequent sexual assault.

The current study was designed to test the hypothesis that, in college women, sexting mediates the relationship between problem drinking and sexual assault, over and above the role of prior victimization. We formed this hypothesis for the following reasons. First, the intent behind sexting often differs between men and women. For example, women are more likely to sext as a way to flirt and men are more likely to interpret a sext message from a woman as implied consent for a sexual experience,25,35–37 which could result in sexual miscommunication, and, in turn, a male perpetrator targeting a woman following a sexting exchange. Second, problem drinking by both the sender and recipient may increase the likelihood of someone sending more disinhibited sexts, and of the recipient interpreting such a sext message as an invitation to engage in sexual activity. Women who are both drinking and sexting may be targeted by perpetrators for sexual assault due to their heightened vulnerability from alcohol effects as well as their perceived sexual interest. Thus, in this way, more frequent problem drinking over time could increase risk for sexual assault through its influence on sexting behaviors.

The current study is the first longitudinal investigation of these relationships measured across three time points across one college school year, and thus the first to test the possibility that sexting behavior could mediate the predictive influences of problem drinking on subsequent sexual assault among college women. We hypothesized that, over one year of college, sexting would mediate the relationship between problem drinking and sexual assault, such that drinking at the beginning of the fall semester would lead to increased sexting behaviors by the end of the fall semester, which would in turn increase the risk of being targeted for sexual assault by the end of the spring semester. Although both men and women are at risk of sexual assault, we focus on college women as victims since rates of reporting sexual assault among college women are higher.38 We also focused on female victimization by male perpetrators as these reports are most prevalent on college campuses.38–39

Method

Participants

Participants were college women recruited from two Midwestern universities (n = 199 and n = 133, total N = 332, Mage = 19.15, SD = 1.69, age range 18–28, 76.9% Caucasian; Table 1), with the overall sample representative of the population demographics at the two institutions (approximately 70% Caucasian, over 50% aged 18–24 at both universities). Participants were recruited online through the psychology subject pool (n = 294) and through the greater campus community (n = 38); Original recruitment was N = 432 participants; n = 332 participants with complete data at all three time points were used for structural equation modeling analyses. There were no significant differences across demographics and study variables for individuals with complete data and those who did not complete the study as well as across the two universities (all at p >.10).

Table 1.

Correlations Among Study Variables

| Sex Assault T1 | Problem Drinking T1 | Sext Frequency T2 | Sex Assault T3 | Age | Relationship status | Race/ethnicity | Sexual Identity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex Assault T1 | 1 | |||||||

| Problem Drinking T1 | .09 | 1 | ||||||

| Sext Frequency T2 | .16** | .14* | 1 | |||||

| Sex Assault T3 | .71** | .07 | .18** | 1 | ||||

| Age | .07 | .26** | .14* | .10 | 1 | |||

| Relationship Status | .10 | .05 | .34** | .05 | .23** | 1 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | −.01 | −.001 | −.08 | .02 | .17** | −.06 | 1 | |

| Sexual Identity | .08 | .05 | .08 | .04 | .05 | .11* | −.04 | 1 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.68 (5.33) | 11.31 (2.07) | 0.11 (0.17) | 2.99 (6.15) | 19.15 (1.69) | |||

| Range | 0–32 | 9–18 | 0–1 | 0–32 | 18–28 |

Note. T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Procedures

Recruitment and data collection procedures were in accordance with IRB approval at both universities. All data collection across three time points was completed online using Survey Monkey and participants were able to complete measures at the location of their choosing. Participants completed Time 1 measures at the beginning of the college year (August/September 2014), Time 2 at the end of the fall semester (December 2014), and Time 3 at the end of the spring semester (May/June 2015). Participants were sent emails with a link to the survey at each time point and were given roughly two weeks to complete the respective time point survey. Participants were compensated upon completion at each time point. Psychology students received course credit and $10 across three data collection time points and non-psychology students received $15 across three data collection time points. All participants were also entered in a raffle to win $50 gift cards as an incentive for their participation at each time of data collection.

Measures

Sexual Experiences Survey (SES).40

The SES was used to measure a range of sexual assault experiences. Eight items assessed various experiences and were phrased in terms of the woman as victim and man as perpetrator, with yes or no response options regarding lifetime incident history. Positive responses across items were summed, so that higher scores reflect a more extensive and severe sexual assault history (Time 1 α = 0.82; Time 3 α = 0.86). We chose a weighted summed score to account for both frequency and severity of experiences.41 Three items were given a score of 1 that related to unwanted sexual experiences obtained from pressure, threat, or lying; three items reflecting attempted sexual intercourse or sexual contact obtained through physical force or threat of physical force a score of 2; three items reflecting sexual intercourse obtained through threat or physical force and one item clearly labeled as rape a score of 3 (see Table 2 for items in each category).40

Table 2.

Prevalence Rates of Sexual Assault.

| Sexual Assault Category | Sexual Experiences Survey items | Time 1 N (%) |

Time 3 N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unwanted sexual intercourse by pressure or threat | Had sex with a man even though you didn’t really want to because you felt pressured? | 83 (25) | 83 (25) |

| Had sex with a man you didn’t really want to because you felt threatened? | 23 (6.9) | 21 (6.3%) | |

| Found out that a man had obtained sex with you by saying things he didn’t really mean? | 79 (23.8) | 88 (26.5) | |

| Attempted or completed sexual contact by threat or force | Been in a situation where a man used physical force to try to make you engage in kissing/petting when you didn’t want to? | 34 (10.2) | 38 (11.4) |

| Been in a situation where a man tried to have sex with you when you didn’t want to by threatening to use physical force if you didn’t cooperate, but sex did not occur? | 15 (4.5) | 23 (6.9) | |

| Been in a situation where a man used physical force to try to get you to have sex with him when you didn’t want to, but sex did not occur? | 23 (6.9) | 27 (8.1) | |

| Completed rape (sex by threat or force) | Had sex with a man when you didn’t want to because he threatened to use physical force if you didn’t cooperate? | 10 (3) | 12 (3.6%) |

| Had sex with a man when you didn’t want to because he used physical force? | 14 (4.2) | 14 (4.2%) | |

| Been in a situation where a man obtained sexual acts with you when you didn’t want to by using threats or physical force? | 16 (4.8) | 24 (7.2%) | |

| Have you ever been raped? | 26 (7.8) | 29 (8.7%) |

Note. Items related to unwanted sexual intercourse by pressure or threat were given a score of 1, items reflecting attempted or completed sexual contact by threat or force were given a score of 2, and items reflecting completed rape (sex by threat or force) were given a score of 3.

Timeline Followback (TLFB).42

A modified online version of the TLFB was created to measure reports of sexting behaviors over the past 30 days (see Pedersen, Grow, Duncan, Neighbors, and Larimer, 2012 for online TLFB syntax and development).43 Individuals were asked for each of the past 30 days whether or not they sent a sext message (yes or no). We defined sexting to participants as sending a sexually suggestive text message or sexual picture based on previous definitions of sexting.24–27 Additionally, we asked participants to report whether the sext was exchanged via mobile phone, via mobile dating app (i.e., Tinder, Bumble), or posted publicly on a personal social media profile. Only participants who reported on at least 14 out of 30 days were included in analyses (n = 332). Sexting frequency was calculated as the percentage of days reported sending a sext out of the total number of days completed across a potential 30-day period in order to account for the heterogeneity in range of days that participants reported (e.g., n = 2 sexting days based on 30 reported days vs. 14 reported days). The current study analyses use sexting frequency from Time 2.

Drinking Styles Questionnaire (DSQ).44

The drinking problem subscale of the DSQ includes 9 dichotomous (yes or no) items assessing experience of various drinking problems and negative outcomes associated with drinking (e.g., experiencing blackouts; hangovers), with higher summed scores signifying more problem drinking (Time 1 α = .79).

Data Analysis

All analyses were done using SPSS, 24.0.45 We used the PROCESS macro46 order to examine the indirect effect of problem drinking (Time 1) on sexual assault (Time 3) through sexting behaviors (Time 2). The PROCESS macro uses the product of coefficients approach to test the indirect effects and reports bootstrap and Monte Carlo confidence intervals to determine significance of indirect effects.46 For the current analyses, problem drinking at Time 1 was entered as the independent variable, sexting frequency at Time 2 was entered as the mediator variable, and sexual assault at Time 3 served as the dependent variable. Sexual assault at Time 1 served as a control variable.

Results

Sexual Assault Incidence

Across both Time 1 and Time 3, the most common sexual assault experience was being forced into sex with a man through pressure or lying (n = 88, 26.5%), followed by being forced into non-intercourse acts after a man used physical force (n = 38, 11.4%; Table 2). These rates are similar to rates of reported non-intercourse victimization (10.5% among college women) occurring by physical force or threat of physical force found in a recent large-scale campus study.38 No differences were seen in rates of sexual assault across age, race, or relationship status (see Table 1).

Longitudinal Mediation Results

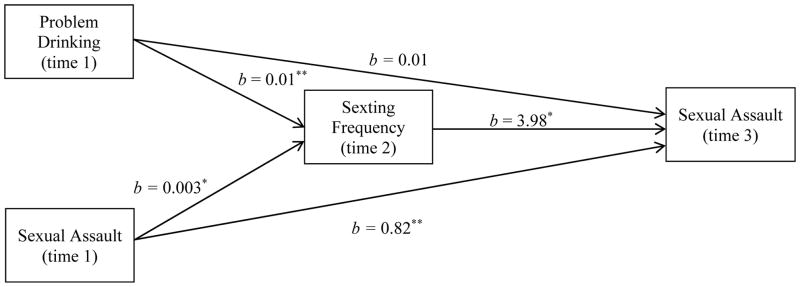

Sexting frequency (Time 2) significantly mediated the relationship between Time 1 problem drinking and Time 3 sexual assault (indirect effect: b = 0.04, CI [.004, .12]), such that problem drinking at Time 1 led to increased sexting frequency at Time 2, which subsequently led to higher risk of sexual assault at Time 3. Additionally, baseline sexual assault and Time 2 sexting frequency significantly predicted later sexual assault (b = 0.82, p < .01 and b = 3.98, p = .05, respectively), while Time 1 problem drinking use was not a significant predictor of later sexual assault (b = −0.01, p = .95). See Figure 1 for mediation model.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal mediation model predicting sexual assault. N = 332. *p < .05. **p < .01. Pathways represent direct effects and values are unstandardized regression coefficients. The indirect effect of problem drinking (time 1 – August/September beginning fall semester) on sexual assault at follow-up (time 3 – May/June end spring semester) through sexting frequency (time 2 – December end fall semester ) was significant (b = 0.04, CI[.004, .12]).

Discussion

The present study investigated whether sexting is a mechanism by which problem alcohol use increases risk for college women to be targeted for sexual assault. Sexting significantly predicted subsequent sexual assault and also mediated the relationship between problem drinking at the beginning of the fall semester and sexual assault at the end of the spring semester, even after controlling for prior sexual assault. In other words, sexting is one mechanism through which problem drinking increases the risk of women being targeted for sexual assault..

We offer two potential reasons for how and why sexting might explain the relationship between problematic drinking and sexual assault. First, men and women engage in sexting for different reasons, 25,35–37 potentially leading to sexual assault through miscommunication of sexual intent and consent, which may be more likely when alcohol is involved. The second possibility involves an additional variable beyond those we studied: The risk for sexual assault could be related to whether or not exchanging sexts was mutual or more coercive. In fact, women – unlike men – often report sexting out of pressure from a partner,36–37,47 and women with a history of experiencing sexual victimization are more likely to experience and engage in coercive and unwanted sexting.48–49 Therefore, future research should examine the types of sexting behaviors – whether the exchange was mutual or coercive – as well as motives and meaning of the messages in order to determine the mechanism through which sexting might contribute to sexual assault risk.

We found that sexting mediated the relationship between problem drinking and sexual assault over the course of nine months, such that problem drinking increased risk for later sexual assault, in part through increases in sexting engagement. The positive findings of this study speak to the importance of further investigation of the relationships among alcohol use, sexting behavior, and sexual assault risk. Specifically, they indicate the value of momentary research, using designs such as ecological momentary assessment, to determine the nature of the immediate, proximal relationships among these variables. There are a number of important research questions. For example, on a given occasion, does problem drinking or heavy alcohol use increase the likelihood of sexting? Is alcohol use associated with more explicit sext messages (i.e., picture vs. text), and are these messages more likely to be misconstrued? Does alcohol use on the part of the recipient of a sext message increase the likelihood of misconstruing the intent of a sext message? Do sext messages in the context of drinking directly result in more frequent sexual encounters? What is the nature of the risk associated with those encounters? Does a given sext message, sent while drinking, increase the likelihood of sexual assault perpetrated by the recipient? Answers to these questions can help guide effective preventive interventions; interventions targeted for perpetrators should focus on consent and sext-interpretation training, while interventions for women and victims should highlight risk and safety information as it relates to sexting behaviors.

A second set of possibilities concerns men who are disposed to coerce sex from women. It is possible that perpetrators or men who engage in sexual coercion perceive a woman as vulnerable and a target for sexual assault if they can coerce explicit sext messages from the woman.48 Thus, it is possible that part or all of the observed longitudinal relationships represent risk associated with the subset of men who are sexual assault perpetrators. If this is the case, it is likely that most sexting behavior is relatively free of risk. A third and related set of possibilities is that problem drinking and sexting behavior may be markers of other risk factors that operate to increase the risk of being targeted for sexual assault.

More importantly, these results offer potential points of intervention and prevention to reduce sexual assault risk. Recent efforts have been made to improve sexual assault risk reduction programs on college campuses, and efforts have also been made to better target related risk factors, such as heavy drinking, as well as tailor programs to individuals at risk for both victimization and perpetration, such as those with a previous history of sexual victimization and those who engage in problem and heavy drinking.50 These recent developments and improvements in sexual assault prevention and intervention also highlight the potential for incorporating sexting and other forms of social media communication in multiple areas of programming that have been shown to be effective, including bystander intervention, sexual assault risk perception, and resistance strategies.51 For example, an intervention point for women might involve increasing awareness about coercive sexual behaviors over social media and enhancing women’s skills and abilities to recognize and end communication with someone who tries to coerce sexting or sexual behavior. Additionally, a prevention point for men might involve education about the meaning of sexting behaviors and how men and women differentially interpret such messages (i.e., women often not intending sexting as consent for sex). Even further, social media may also be a primary prevention point for coercive men or perpetrators.

The current study findings should be interpreted within study limitations. First, sample attrition, likely worsened by the online nature of the study (which is less personable and potentially reduces participants’ accountability to the study) and the length of time between assessment periods, could have affected study findings. For example, women who experienced sexual assault could have dropped out of the study at a higher rate than those not experiencing such encounters. However, there were no significant group differences in those that did and did not finish the study on baseline reports of sexual assault. Still, unknown differences could have emerged over time and could have contributed to limited rates of sexual assault reported at Time 3, thus limiting power to detect relationships. Additionally, the study utilized self-reporting of sensitive and socially undesirable behaviors, which could have led to under-reporting of occurrences of some of these behaviors. The current sample focused on a high-risk group of college women, but the sample was predominantly young and Caucasian, so it is unclear how results would generalize to other, more heterogeneous samples. Still, this sample was representative of the institutions, and thus, these results may be important for campus sexual assault programs at these institutions. The study also focused on women as victims of sexual assault by male perpetrators; however, further research examining sexual assault risk across gender identity and sexual preference, as well as across different relationship dynamics is warranted.

Further, the type and nature of the sext were not examined. As mentioned previously, it is possible that there are different degrees of sexting that influence risk, such as whether a provocative picture is more suggestive compared to a provocative text. Also, the nature of the sext, such as whether one is coerced into sexting could play a role in the risk process. Additionally, other conditions, such as whether or not the sext was exchanged while the sender and/or receiver was using alcohol was not examined. Although we did not measure the drinking behavior of the perpetrators in this study, it is certainly possible that (1) drinking by the woman is associated with drinking by the man and (2) drinking by the man could increase the likelihood of misinterpreting a sext as an invitation for sexual activity. These and other possibilities merit further exploration in the effort to understand the role of sexting in the well-documented relationship between drinking and unwanted sexual experiences5 and sexual assault studies.52–54

In conclusion, this was the first study to longitudinally establish sexting as a mediator in how problem drinking predicts subsequent risk for sexual assault. The current findings suggest the value of research into the mechanisms by which this might occur, in order to develop more effective prevention and intervention programs for both victims and perpetrators. Relatedly, with the increase in social media and apps that are meant for dating and finding partners, research is warranted to determine how these apps may be a vehicle for sexual encounters and assault risk.

References

- 1.Danielson CK, Holmes MM. Adolescent sexual assault: an update of the literature. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;16(5):383–388. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200410000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher BS, Daigle LE, Cullen FT. What distinguishes single from recurrent sexual victims? The role of lifestyle-routine activities and first-incident characteristics. Justice Quarterly. 2010;27(1):102–29. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Classen CC, Palesh OG, Aggarwal R. Sexual revictimization a review of the empirical literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2005;6(2):103–29. doi: 10.1177/1524838005275087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danielson CK, Amstadter AB, Dangelmaier RE, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. Trauma-related risk factors for substance abuse among male versus female young adults. Addict Behav. 2009;24:395–399. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ullman SE. Sexual revictimization, PTSD, and problem drinking in sexual assault survivors. Addict Behav. 2016;53:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flack WF, Daubman KA, Caron ML, Asadorian JA, D’Aureli NR, Gigliotti SN, Hall AT, Kiser S, Stine ER. Risk factors and consequences of unwanted sex among university students hooking up, alcohol, and stress response. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22(2):139–57. doi: 10.1177/0886260506295354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jina R, Thomas LS. Health consequences of sexual Violence Against Women. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2013;27:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Najdowski CJ, Ullman SE. Prospective effects of sexual victimization on PTSD and problem drinking. Addict Behav. 2009;34(11):965–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turchik JA, Hassija CM. Female sexual victimization among college students: Assault severity, health risk behaviors, and sexual functioning. J Interpers Violence. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0886260513520230. 0886260513520230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ullman SE, Najdowski CJ, Filipas HH. Child sexual abuse, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use: Predictors of revictimization in adult sexual assault survivors. J Child Sex Abuse. 2009;18(4):367–85. doi: 10.1080/10538710903035263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Messman-Moore TL, Ward RM, Brown AL. Substance use and PTSD symptoms impact the likelihood of rape and revictimization in college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24(3):499–521. doi: 10.1177/0886260508317199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Combs JL, Jordan CE, Smith GT. Individual differences in personality predict externalizing versus internalizing outcomes following sexual assault. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2014;6(4):375. doi: 10.1037/a0032978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbey A. Alcohol’s role in sexual violence perpetration: Theoretical explanations, existing evidence and future directions. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2011;30:481–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Testa M, Parks KA, Hoffman JH, Crane CA, Leonard KE, Shyhalla K. Do drinking episodes contribute to sexual aggression perpetration in college men? J Stud Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;76(4):507–15. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown SA, Christiansen BA, Goldman MS. The Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire: an instrument for the assessment of adolescent and adult alcohol expectancies. J Stud Alcohol. 1987;48(5):483–91. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1987.48.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dermen KH, Cooper ML. Sex-related alcohol expectancies among adolescents: II. Prediction of drinking in social and sexual situations. Psychology of Addict Behav. 1994;8:161–168. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.8.3.161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.George WH, Gournic SJ, McAfee MP. Perceptions of postdrinking female sexuality: effects of gender, beverage choice, and drink payment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1988;18(15):1295–316. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maurer TW, Robinson DW. Effects of attire, alcohol, and gender on perceptions of date rape. Sex Roles. 2008;58(5–6):423–34. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farris C, Treat TA, Viken RJ, McFall RM. Sexual coercion and the misperception of sexual intent. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28:48–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prause N, Staley C, Finn P. The effects of acute ethanol consumption on sexual response and sexual risk-taking intent. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40(2):373–84. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9718-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis KC, George WH, Norris J. Women’s responses to unwanted sexual advances: The role of alcohol and inhibition conflict. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:333–343. [Google Scholar]

- 22.George WH, Davis KC, Norris J, Heiman JR, Stoner SA, Schacht RL, Hendershot CS, Kajumulo KF. Indirect effects of acute alcohol intoxication on sexual risk-taking: The roles of subjective and physiological sexual arousal. Arch Sex Behav. 2009;38(4):498–513. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9346-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Testa M, Livingston JA, Collins RL. The role of women’s alcohol consumption in evaluation of vulnerability to sexual aggression. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;8(2):185. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klettke B, Hallford DJ, Mellor DJ. Sexting prevalence and correlates: A systematic literature review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(1):44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dir AL, Coskunpinar A, Cyders MA. Understanding differences in sexting behaviors across sex, relationship status, and sexual orientation, and the role of socially learned sexting expectancies in sexting. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2013;16:68–574. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drouin M, Vogel KN, Surbey A, Stills JR. Let’s talk about sexting, baby: Computer-mediated sexual behaviors among young adults. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29(5):A25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lenhart A. Teens and sexting. Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2009. Retrieved from http://pewresearch.org/assets/pdf/teens-and-sexting.pdfLevy. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benotsch EG, Snipes DJ, Martin AM, Bull SS. Sexting, substance use, and sexual risk behavior in young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(3):307–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dake JA, Price JH, Maziarz L, Ward B. Prevalence and correlates of sexting behavior in adolescents. American Journal of Sexuality Education. 2012;7(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dir AL, Coskunpinar A, Cyders MA. From the bar to the bed via mobile phone: A first test of the role of problematic alcohol use, sexting, and impulsivity-related traits in sexual hookups. Computers and Human Behavior. 2013;29:1664–1670. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dir AL, Cyders MA. Risks, risk factors, and outcomes associated with phone and internet sexting among university students in the United States. Arch Sex Behav. 2015:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0370-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.George WH, Stoner SA, Norris J, Lopez PA, Lehman GL. Alcohol expectancies and sexuality: a self-fulfilling prophecy analysis of dyadic perceptions and behavior. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61(1):168–76. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. J Stud Alcohol, supplement. 2002;14:101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper ML. Does drinking promote risky sexual behavior? A complex answer to a simple question. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15(1):19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dir AL, Coskunpinar A, Steiner JL, Cyders MA. Understanding differences in sexting behaviors across gender, relationship status, and sexual identity, and the role of expectancies in sexting. 2013. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2013;16(8):568–574. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lippman JR, Campbell SW. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t… if you’re a girl: Relational and normative contexts of adolescent sexting in the United States. Journal of Children and Media. 2014;8(4):371–86. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walker S, Sanci L, Temple-Smith M. Sexting: Young women’s and men’s views on its nature and origins. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(6):697–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cantor D, Fisher B, Chibnall SH, Townsend R, Lee H, Thomas G, Bruce C Westat, Inc. Report on the AAU campus climate survey on sexual assault and sexual misconduct. Washington, DC: Association of American Universities; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Budd KM, Rocque M, Bierie DM. Deconstructing incidents of campus sexual assault: comparing male and female victimizations. Sexual Abuse. 2017:1. doi: 10.1177/1079063217706708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koss MP, Oros CJ. Sexual Experiences Survey: a research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1982;50(3):455. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abbey A, BeShears R, Clinton-Sherrod AM, McAuslan P. Similarities and differences in women’s sexual assault experiences based on tactics used by the perpetrator. Psychology of Women quarterly. 2004;28:323–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. In measuring alcohol consumption. Humana Press; 1992. Timeline follow-back; pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pedersen ER, Grow J, Duncan S, Neighbors C, Larimer ME. Concurrent validity of an online version of the Timeline Followback assessment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(3):672. doi: 10.1037/a0027945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith GT, McCarthy DM, Goldman MS. Self-reported drinking and alcohol-related problems among early adolescents: dimensionality and validity over 24 months. J Studies Alcohol. 1995;56(4):383–94. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corporation; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayes AF. [accessed Oct. 3, 2016];PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper] 2012 http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

- 47.Walrave M, Heirman W, Hallam L. Under pressure to sext? Applying the theory of planned behaviour to adolescent sexting. Behaviour & Information Technology. 2014;33(1):86–98. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drouin M, Ross J, Tobin E. Sexting: A new, digital vehicle for intimate partner aggression? Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;50:197–204. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Drouin M, Tobin E. Unwanted but consensual sexting among young adults: Relations with attachment and sexual motivations. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;31:412–418. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gilmore AK, Lewis MA, George WH. A randomized controlled trial targeting alcohol use and sexual assault risk among college women at high risk for victimization. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2015;74:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anderson LA, Whiston SC. Sexual assault education programs: A meta-analytic examination of their effectiveness. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29(4):374–388. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Combs-Lane AM, Smith DW. Risk of sexual victimization in college women: The role of behavioral intentions and risk-taking behaviors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17(2):165–83. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gidycz CA, Warkentin JB, Orchowski LM. Predictors of perpetration of verbal, physical, and sexual violence: A prospective analysis of college men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2007;8(2):79–94. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Messman-Moore TL, Coates AA, Gaffey KJ, Johnson CF. Sexuality, substance use, and susceptibility to victimization: Risk for rape and sexual coercion in a prospective study of college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(12):1730–1746. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]