Abstract

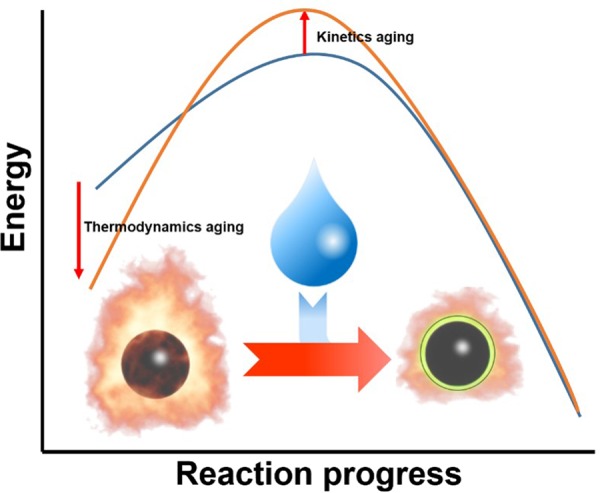

The aging of propellants in PMDs is considered to be one of the primary factors affecting the performance of PMDs. Thus, studies on the aging mechanism of propellants, which have not yet been addressed extensively, pose a solution to securing the sustainable operation of PMDs. We characterized one of the most commonly used commercial propellants (boron potassium nitrate (BKNO3)) and investigated its aging mechanism rigorously. Based on thermal analyses, we demonstrate that the decomposition of laminac, a polymer binder, is the fastest spontaneous reaction. However, it will not self-initiate at a storage temperature as high as 120 °C. The effect of the humidity level was examined by characterizing BKNO3 samples prepared. The heat of reaction and the reaction rate decreased by 18% and 67% over 16 weeks of aging, respectively. This is attributed to the oxide shells on the surface of boron particles. The formation of oxide shells could be confirmed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and transmission electron microscopy–energy dispersive spectroscopy. In conclusion, surface oxide formation with the aging of BKNO3 will decrease its propulsive efficiency; oxidation reduces the potential energy of the system and the resulting oxide decreases the reaction rate.

Introduction

Pyrotechnic mechanical devices (PMDs) that utilize pressure through explosions are a highly attractive topic in aerospace industries1. In such devices, zirconium potassium perchlorate (ZPP), boron potassium nitrate (BKNO3), and titanium hydride potassium perchlorate (THPP) are used as propellants (or pyro-initiators)2–4. These three types of propellants must have long-term stability to be utilized in practical applications5. That is, the reaction heat and reaction rate should be constant even after a long period of time. However, most PMDs are disposed periodically because of the aging phenomena of the propellants. Increasing the disposal period of explosives through research on the aging mechanism and controlling the aging can lead to a huge reduction in a national defense budget6.

Common PMDs comprise three components: an oxidizer, binder, and metal. The aging phenomena of explosives are considered to be caused by physical or chemical transitions through spontaneous reactions7–11 or by external factors such as humidity12–16. These phenomena can also be divided into thermodynamic and kinetic aspects. Thermodynamic aging means the reduction of the reaction heat in an explosion, resulting from a decrease in the energy level of reactants due to pre-chemical reactions among the components17 or due to external factors. On the other hand, kinetic aging leads to a decreased combustion rate and increased activation energy upon the formation of products because of side products and impurities. It can induce a reduction in the peak pressure of PMDs despite the constant heat of the reaction18,19.

Here, we investigate the aging mechanism of BKNO3, which is well known to possess a higher peak pressure than that of the other two commonly used propellants (THPP and ZPP)20–24. Previous study on the aging of BKNO3 emphasized only pressure in PMD devices6. However, to clarify the mechanism, side chemical reaction of the propellant should be analyzed. BKNO3 comprises three components: boron, potassium nitrate, and laminac. Boron plays the role of an oxidization source in explosions25, whereas potassium nitrate (KNO3) donates oxygen to boron26. Laminac is a commercial polymer binder that causes boron and KNO3 to bind together closely27. A typical mixing ratio of these components is 23.7:70.7:5.6 on a weight percentage basis. In this system, boron reacts with KNO3, producing potassium metaborate (KBO2) exothermically. The resulting heat produces auto-acceleration, causes an explosion, and produces high pressure for the propulsion of PMDs28. Although boron is highly stable at high humidity levels and ambient temperatures, it is known to yield boronic acid (RB(OH)2) and boron oxide (B2O3) at above 300 °C29. Aging (mostly oxide formation) due to humidity should thus be considerable during the incorporation process into PMDs wherein the propellants are exposed to a very high humidity level to prevent an undesirable explosion (Fig. 1). However, aging due to external factors is less of an issue after this because BKNO3 is sealed in the PMDs. It is now necessary to consider internal factors for any further spontaneous aging for KNO3 and laminac. KNO3, a strong oxidizer, decomposes into KNO2 and oxygen at above 550 °C26. Therefore, the decomposition of KNO3 over an extended period can possibly induce undesirable pre-reactions with boron and decrease the energy level of the reactants. Moreover, the decomposition of laminac, which comprises polyester, results in micro phase separation. The reduced contact area between boron and KNO3 particles lowers the combustion rate and increases the activation energy30.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of aging mechanism of the propellant (BKNO3). The efficiency of the propellant is decreased by forming oxide shells on boron surfaces from humidity aging.

To investigate the aging of BKNO3 due to internal factors, we preferentially employed thermal analyses such as thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)31. Spontaneous aging and its mechanisms were simulated using advanced kinetics and technology solutions (AKTS) with DSC data. The AKTS program is based on the Arrhenius–Sesták–Berggren theory that treats the reaction rate according to the activation energy, temperature, and reaction progress32. The equation is shown below,

| 1 |

where α is the reaction progress, E is the activation energy, and A, n, and m are reaction constants.

To investigate external factors, BKNO3 samples prepared under accelerated aging at 71 °C with a 50% relative humidity were characterized to measure the heats of reaction and the reaction rates using DSC profiles. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)33 and a transmission electron microscope (TEM) equipped with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) were also used to confirm the oxidization of boron and identify oxide shells34 on the boron surface. The formation of surface oxide is supposed to decrease the potential energy (explosive energy) of the system and disturb the propagation of combustion10.

Results

Thermal properties of BKNO3

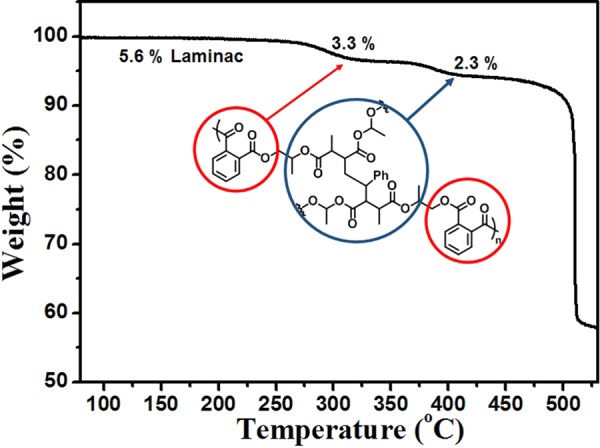

The TGA curve shown in Fig. 2 for BKNO3 in a nitrogen atmosphere indicates its thermal stability and the degradation of each component. There are three stages of weight loss in the TGA plot, indicating that the decomposition of the BKNO3 sample initiated at around 300, 410, and 500 °C. The first two stages are attributed to the weak stability of ester groups35 in laminac and the weight losses were 3.3% and 2.3%, respectively. The polymer binder was perfectly decomposed at 410 °C with a total weight loss of 5.6%. In the third stage, the oxidization of boron with KNO3 occurs, accompanied by a remarkable weight loss. The oxidization is the main reaction of the propellants, finally producing nitrogen dioxide gas28,36.

Figure 2.

The TGA curve of BKNO3. The decomposition of laminac occurs from around 300 °C to 400 °C.

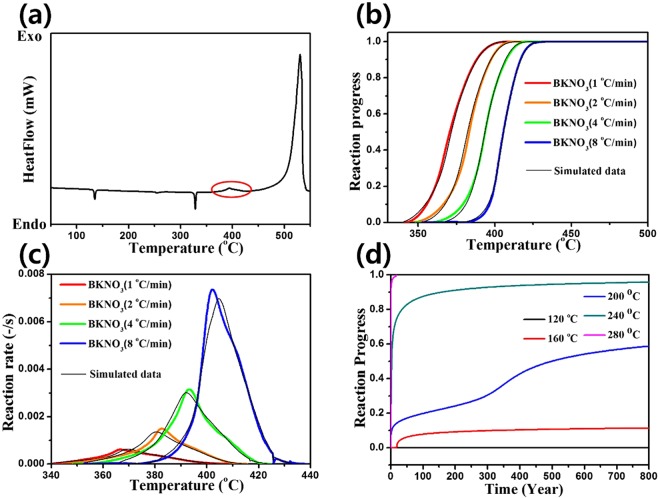

In the DSC profiles shown in Fig. 3a, there are two types of exothermic reactions37. Ahead of the primary exothermic peak from boron oxidization at around 500 °C, a weak exothermic peak due to the decomposition of laminac was detected at 400 °C38. The exothermic decomposition of laminac at a relatively low temperature suggests that over an extended period, it is more likely to occur than primary boron oxidation. Therefore, the breakdown of laminac could affect the kinetic aging of the overall system by changing the morphology or internal structure of BKNO338,39.

Figure 3.

(a) The DSC profile of BKNO3. The first exothermic reaction is the decomposition of laminac (red circle) (b) Reaction progress vs. temperature and (c) reaction rate vs. temperature compared for various heating rates (1, 2, 4, and 8 °C/min). (d) Long-period reaction progress vs. time at various storage temperatures. Although the storage temperature is high (120 °C), the initiation of reaction (the decomposition of laminac) takes an infinite time.

Kinetic simulation for laminac decomposition

The simulated AKTS data are shown in Fig. 3b–d. AKTS was adopted to calculate the reaction progress and reaction rate according to the heating rate of the DSC data (Fig. 3b,c). It was also adopted to determine the long-term reaction progress related to the storage temperature (Fig. 3d) using the DSC data with varying heating rates (1, 2, 4, and 8 °C/min) (Supplementary Fig. S1). Here, the first exothermic reaction of laminac decomposition was studied to simulate its kinetic behavior. The resulting error factor of the simulation was about 0.08%, indicating an accurate estimation of the long-period reaction progress.

The reaction progress according to the heating rate is shown in Fig. 3b. The reaction progress α(t) of a DSC profile is expressed as

| 2 |

where S(t) is a DSC signal as a function of time with respect to the temperature and B(t) is the baseline determining the amount of heat flow. The reaction progress at the temperature related to time (heating rate) is calculated using the summation of the released energy divided by the total released energy40

Laminac decomposition initiates (the reaction progress >0.05) at a higher temperature when increasing the heating rate. (Table 1) due to the relaxation time41. To investigate the reaction rate as a function of the temperature by varying the heating rate, we converted DSC data using AKTS. The relevant equation is expressed below40.

| 3 |

As shown in Fig. 3c and Table 1, the reaction rate increases when the heating rate is increased. Excess heat due to a high heating rate is imposed on the samples, and thus the initiation of laminac decomposition occurs at a relatively high temperature kinetically.

Table 1.

Initiation temperatures and peak reaction rates of laminac decomposition at various heating rates.

| Heating rate (°C/min) | Initiation Temp. (°C) | Peak reaction rate (10−3-/s) |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment/Simulation | ||

| 1 | 351/349 | 0.61/0.63 |

| 2 | 360/362 | 1.5/1.4 |

| 4 | 373/377 | 3.1/3.0 |

| 8 | 393/391 | 7.4/7.0 |

Data are converted and simulated from DSC signals using the AKTS program.

In the Arrhenius theory, the temperature exponentially increases the rate constant or reaction rate42. Ultimately, we are able to predict the reaction initiation time by utilizing Arrhenius theory to confirm the long-term stability of BKNO3. The equation is expressed below through the respective α vs. t reaction profiles using integration.

| 4 |

The simulated values are shown in Fig. 3d and Table 2, representing that the long-period reaction progress with time is dependent on the storage temperature. Although an increase in the storage temperature generally leads to earlier initiation of the decomposition of laminac, it will not start at 120 °C over 800 years, which is the time scale limitation of the AKTS program. In conclusion, the aging of BKNO3 due to the deformation of laminac will require infinite time at ambient temperatures. Thus, the aging probably does not originate from internal factors but from external factors such as the humidity level13.

Table 2.

Initiation time according to the storage temperature.

| Storage temperature (°C) | Initiation time |

|---|---|

| 120 | Over 800 years |

| 160 | 18 years |

| 200 | 5 months |

| 240 | 1 week |

| 280 | 1 day |

Data are simulated from DSC signals using the AKTS program.

Aging mechanism analysis under accelerated aging

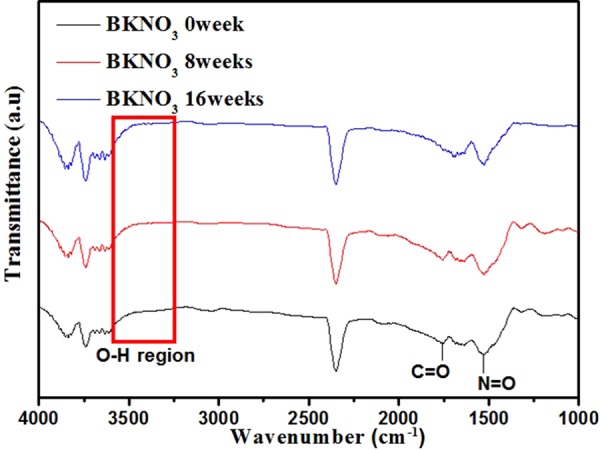

Humidity is a crucial external factor for boron oxidization, resulting in undesirable pre-reactions and decreasing the efficiency of BKNO3, despite the fact that only the surfaces of boron particles are oxidized10. First, laminac degradation due to humidity was tested using IR spectroscopy under accelerated aging at 71 °C with 50% RH. KNO3 can react with water vapor, yielding HNO3, a highly acidic material (pKa = −1.0)43. Laminac possibly leads to the hydrolysis of ester bonds in laminac. The resulting hydroxyl group and carboxylic acid groups are evidence of the degradation of laminac. As shown in Fig. 4, the C=O stretching band around 1700 cm−1 is attributed to the existence of ester bonds in laminac. The N=O stretching band of KNO3 was also detected at around 1500 cm−1. The bands around 4000–3600 cm−1 and 2350 cm−1 originate from carbon dioxide in the atmosphere during the experiments44. Here, it is noted that there is no band for O-H stretching at around 3400 cm−1, suggesting that humidity does not affect laminac degradation45.

Figure 4.

FTIR-spectra of BKNO3 under accelerated aging. The hydroxyl group could not be observed, which demonstrates that there is no hydrolysis of laminac

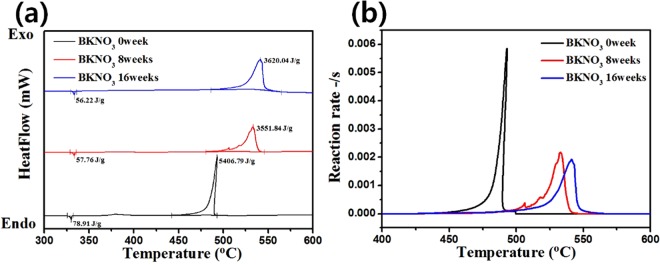

Accelerated aging samples were characterized to confirm boron oxidization caused by humidity. The relative heats released by thermodynamic aging and reaction rates for kinetic aging were obtained. In addition, the B-O bond and boron oxide shells on the surface were identified using XPS and TEM–EDS, respectively10.

DSC experiments were conducted on the BKNO3 samples under accelerated aging at 71 °C with 50% RH for 8 and 16 weeks. It showed that exothermic reactions occur at an onset temperature of around 530 °C (Fig. 5a). The relative heats of reaction, wherein the heat of reaction is divided by the melting heat of KNO3, are listed in Table 3. The melting heats of KNO3 were obtained from the DSC profiles of pristine, 8, and 16 week samples as 78.91, 57.76 and 56.22 J/g, with heats of reaction of 5406.79, 3551.84, and 3620.04 J/g, respectively. To compensate for the error attributed to highly energetic materials such as explosives, relative values were introduced. The relative heats released were 68.51, 61.53, and 56.44 for the pristine, 8, and 16 weeks-aged boron particles, respectively. This value decreases by up to 18% when compared with that of the pristine sample. In contrast, the samples without induced humidity exhibited rather constant values even after 12 months of aging (Supplementary Fig. S2a and Table S1). It is thus concluded that thermodynamic aging is obviously induced by humidity and progresses gradually over time. Moreover, the reaction rates, which are converted from DSC signals using the AKTS program, are plotted in Fig. 5b and are listed in Table 3. Peak reaction rates of 5.86 × 10−3 s−1, 2.17 × 10−3 s−1, and 1.93 × 10−3 s−1 were calculated for the pristine, 8, and 16 week BKNO3 samples, respectively. The reaction rate decreases by 67% over 16 weeks; in other words, kinetic aging occurs. This can be attributed to oxide formation on the boron surface, which plays a role as a barrier to heat propagation, reducing the contact area between boron and KNO3, and finally increasing the activation energy for combustion46. In contrast, a difference in the reaction rates was not found for no induced humidity (Supplementary Fig. S2b and Table S1), suggesting that kinetic aging also originates from humidity.

Figure 5.

(a) DSC profiles and (b) reaction rates of BKNO3 under accelerated aging. The relative heat of explosion and reaction rate gradually decreased along with extension of humidity aging periods (8 and 16 weeks).

Table 3.

The relative heats, peak reaction rates, and thickness of oxide shells of BKNO3 under accelerated aging.

| Aging week | Relative ΔHreleased | Peak reaction rate (10−3-/s) | Thickness of oxide shells (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 68.51 | 5.86 | 0 |

| 8 | 61.53 | 2.17 | 26 |

| 16 | 56.44 | 1.93 | 39 |

Relative heats released ( = reaction heat/melting heat of KNO3) and reaction rates are converted from DSC signals using the AKTS program.

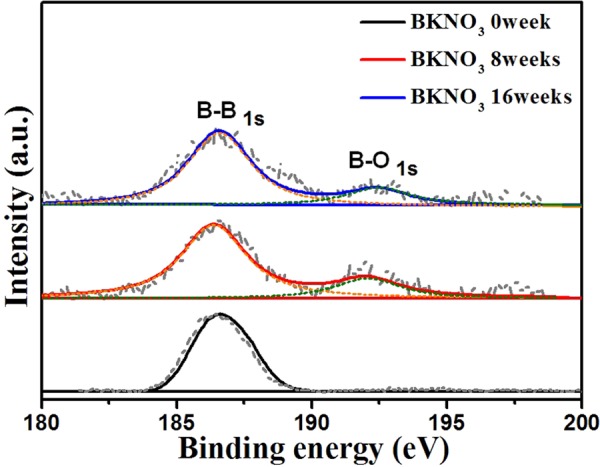

XPS measurements of the BKNO3 samples under accelerated aging are shown in Fig. 6. The B 1 s core electron peak (186.6 eV) is clearly distinguishable from its oxidization state at around 191.5 eV10,33. The strongest signal centered at 186.6 eV is typically assigned to the B-B bond of elemental boron. The weak signal at 191.5 eV is due to the B-O bonds in boron oxides. The pristine BKNO3 exhibited only the B-B bond signal. In contrast, the B-O bond was detected in both 8 and 16 week samples. This is obviously caused by oxidization between boron and water vapor (humidity). The experiments without induced humidity are good counter evidences for the effect of humidity on the oxidation, wherein both samples stored for 6 and 12 months without induced humidity displayed the B-B bond signals only at 186.6 eV (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Figure 6.

XPS spectra of BKNO3 under accelerated aging. In aging samples of 8 and 16 weeks, B-O 1 s peak was observed. It is an evidence of formation of oxide shells on the boron surface.

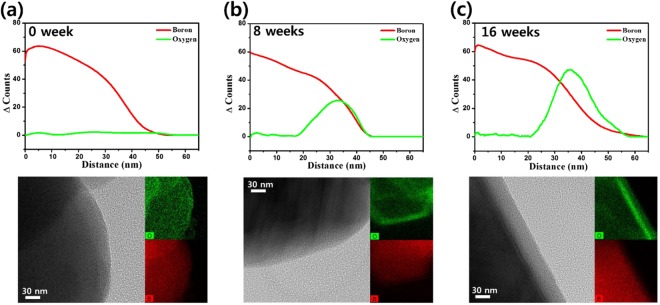

The formation of oxide shells is visualized using TEM–EDS in Fig. 7 and Table 347. In the TEM–EDS images, the edges of boron particles under accelerated aging have high counts of oxygen, whereas no oxygen was detected in the pristine sample. Furthermore, the thicknesses of oxide shells gradually increased with time, up to 26 nm and 39 nm for 8 and 16 week samples, respectively. Likewise, oxide shells did not develop for the samples stored at 71 °C without induced humidity for 12 months (Supplementary Fig. S4). That is, both kinetic and thermodynamic aging are induced by humidity levels.

Figure 7.

TEM–EDS characterizations of BKNO3s under accelerated aging. The thickness of oxide shells gradually increased along with the extension of humidity aging. It corresponds to the tendency of thermal analysis such as relative heat and reaction rate.

Discussion

We intensively investigated the aging mechanism of a well-known propellant for PMDs (BKNO3). This is essential to secure the sustainable performance of PMDs. The origin of aging was divided into internal factors such as spontaneous pre-reactions and external factors such as humidity levels. First, AKTS simulations combined with thermal analyses confirmed that the decomposition of laminac (a polymer binder) is the fastest exothermic reaction of BKNO3, but will not initiate over 800 years even at a storage temperature of 120 °C. The effects of internal factors were ruled out in this way. As for the humidity level (the main external factor), BKNO3 samples under accelerated aging at 71 °C in 50% RH were characterized. The heat of reaction and reaction rate, which are related to thermodynamic and kinetic aging, respectively, decreased gradually over time; the heat of reaction decreased by 18% over 16 weeks, whereas the reaction rate decreased by 67%. XPS analysis exhibited a B-O peak (around 191.5 eV) due to boron oxidization. The resulting surface oxide shells were identified through TEM–EDS studies. The thicknesses of oxide shells gradually increased up to 39 nm over 16 weeks and were reciprocally related to the heat of reaction and the reaction rate. In conclusion, the primary origin of BKNO3 aging is the high humidity condition present during the incorporation process of propellants into PMDs to prevent undesirable explosions. The high humidity level leads to the formation of oxide shells on the boron surface and their presence lowers the potential energy (explosive energy) of the system. The reaction rate is also reduced because the oxide shells play a role as a barrier to heat propagation and the contact between boron and KNO3.

Methods

Materials

Potassium nitrate particles of around diameter of 6 µm were purchased from Hummel Croton. Highly pure amorphous boron powder with a particle size of around diameter of 1 µm was prepared by Rockwood Lithium, and the polymer binder (LAMINAC 4116) was purchased from Ashland.

Accelerated aging method

The BKNO3 propellants were stored in a furnace that sustained the temperature at 71 °C. The humidity level was then controlled by storing the samples in a 4.7 L airtight container. Relative humidity (RH) was calculated using the ideal gas law and water vapor pressure at 71 °C. For example, 0.47 g of purified water was incorporated in the airtight container to produce a RH of 50%. The calculation procedure for 50% RH is shown in Eqns (2) and (3).

The mole of water (50% RH 4.7L 71 °C)

| 5 |

The amount of water (50% RH 4.7L 71 °C)

| 6 |

TGA analysis

Investigations using Q500 V50 were conducted while heating the samples from 30 to 550 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere. The weight of the BKNO3 sample for each measurement was about 10 mg and thermogravimetric signals were recorded.

DSC measurements & AKTS simulation

DSC was performed using a DSC 4000 (PerkinElmer). DSC data for AKTS simulations were obtained at various heating rates (1, 2, 4 and 8 °C/min.). In addition, the measurements of the heats of reaction were conducted while heating the samples to 600 °C at a scanning rate of 2 °C/min. A slow heating rate could generate thermodynamic information with a sufficient relaxation time. Kinetic analysis of the thermally simulated processes with AKTS used the DSC data with various heating rates.

IR spectroscopy

Fourier transform infrared spectra were obtained using a Cary 600 spectrometer equipped with a MCT-A (mercury cadmium telluride) detector with 5 mg samples in a powdered state.

XPS characterizations

The XPS spectra were obtained using a MultiLab 2000 with monochromated Al Kα X-rays and a hemispherical analyzer with a pass energy of 30 eV. The BKNO3 samples were prepared on conductive copper tape. Background subtraction was performed using a Shirley background and MonoXPS.

TEM–EDS images

TEM images, elemental mapping, and EDS were performed using a Titan G2 ChemiSTEM Cs Probe (FEI Company, Netherlands) with an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. The samples for the TEM observations were prepared by immersing a TEM mesh into a boron particle suspension in ethanol. After being dried in air, the TEM mesh was then characterized.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Agency for Defence Development under the Precise Energy Release for the Pyrotechnic Mechanical Device program and the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) and the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE) of the Republic of Korea (No. 20174010201460).

Author Contributions

T.P., B.R., J.G.P., Y.S.W. and J.L. designed the study. J.L. and T.K. conceived the experiment and S.U.R., G.H.A. and K.C. conducted experiments. J.L. analyzed the results. T.P., Y.S.W. and J.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Taiho Park, Email: taihopark@postech.ac.kr.

Yong Sun Won, Email: yswon@pknu.ac.kr.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-29412-8.

References

- 1.Bement LJ, Multhaup HA. Determining functional reliability of pyrotechnic mechanical devices. AIAA Journal. 1999;37:357–363. doi: 10.2514/2.737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JS, et al. A study of zirconium/potassium perchlorate primer mixtures. Thermochim. Acta. 1990;173:211–218. doi: 10.1016/0040-6031(90)80606-Y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ulas A, Risha GA, Kuo An KK. Investigation of the Performance of a Boron/Potassium‐Nitrate Based Pyrotechnic Igniter. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 2006;31:311–317. doi: 10.1002/prep.200600047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan N, Bao B, Zheng F, Li C. Ignition Characteristics of Micro-Energy Semiconductor Bridges with Different Ignition Compositions. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 2016;41:223–227. doi: 10.1002/prep.201500206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olmos RP, et al. Construction and evaluation of ion selective electrodes for perchlorate with a summing operational amplifier: application to pyrotechnics mixtures analysis. Analyst. 1999;124:97–100. doi: 10.1039/a806919k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.K. S. Lai Boron potassium nitrate (BKNO3) aging study In AIAA, ASME, SAE, and ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibition (1998).

- 7.Gilbert EE, Sollot Explosive GP. compound undergoes testing. Chem. Eng. News. 1980;58:32. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunter LW, White JW, Cohen PH, Biermann PJ. A materials aging problem in theory and practice. Johns Hopkins APL Tech. Dig. 2000;21:575–581. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorzynski CS, Maycock JN. Explosives and pyrotechnic propellants for use in long term deep space missions. J. Spacecraft Rockets. 1974;11:211–212. doi: 10.2514/3.62044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellott BJ, Noh W, Nuzzo RG, Girolami GS. Nanoenergetic materials: boron nanoparticles from the pyrolysis of decaborane and their functionalisation. Chem. Commun. 2009;22:3214–3215. doi: 10.1039/b902371b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel VK, Ganguli A, Kant R, Bhattacharya S. Micropatterning of nanoenergetic films of Bi2O3/Al for pyrotechnics. RSC Adv. 2015;5:14967–14973. doi: 10.1039/C4RA15476B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sorensen DN, Quebral AP, Baroody EE, Sanborn WB. Investigation of the thermal degradation of the aged pyrotechnic titanium hydride/potassium perchlorate. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2006;85:151. doi: 10.1007/s10973-005-7365-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paik JG, Ryu BT, Kwon M. A Study on Acceleration Aging Characteristics of B-KNO3 Igniter. Korean Chem. Eng. Res. 2014;52:166–174. doi: 10.9713/kcer.2014.52.2.166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le AQ, Sun LZ, Miller TC. Detectability of delaminations in solid rocket motors with embedded stress sensors. J. Propul. Power. 2013;29:299–304. doi: 10.2514/1.B34523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosseinia SG, Pourmortazavia SM, Hajimirsadeghi SS. Thermal decomposition of pyrotechnic mixtures containing sucrose with either potassium chlorate or potassium perchlorate. Combust. Flame. 2005;141:322–326. doi: 10.1016/j.combustflame.2005.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown SD, et al. Studies on the ageing of a magnesium–potassium nitrate pyrotechnic composition using isothermal heat flow calorimetry and thermal analysis techniques. Thermochim. Acta. 2003;401:53–61. doi: 10.1016/S0040-6031(03)00055-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pakkirisamya SV, Mahadevana S, Paramashivanb SS, Baran Water MA. induced thermal decomposition of pyrotechnic mixtures–Thermo kinetics and explosion pathway. J. Loss Prevent. Proc. 2014;30:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jlp.2014.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sivan J, et al. Boron particle size effect on B/KNO3 ignition by a diode laser. Combust. Flame. 2015;162:516–527. doi: 10.1016/j.combustflame.2014.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouyang D, et al. Effect of different additives on the thermal properties and combustion characteristics of pyrotechnic mixtures containing the KClO4/Mg–Al alloy. Thermochim. Acta. 2011;513:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.tca.2010.11.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roduit B, et al. Advanced kinetic tools for the evaluation of decomposition reactions: determination of thermal stability of energetic materials. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2005;80:229–236. doi: 10.1007/s10973-005-0641-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeh CL, Kuo KK. Ignition and combustion of boron particles. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 1997;22:511–541. doi: 10.1016/S0360-1285(96)00012-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Natan B, Gany A. Ignition and combustion of boron particles in the flowfield of a solid fuel ramjet. J. Propul. Power. 1991;7:37–43. doi: 10.2514/3.23291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gany A, Netzer DW. Combustion studies of metallized fuels for solid-fuel ramjets. J. Propul. Power. 1986;2:423–427. doi: 10.2514/3.22924. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berger B. Military pyrotechnics. Chimia. 2004;58:363–368. doi: 10.2533/000942904777677678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu TL, Shyu IM, Hsia YS. Effect of fluorinated graphite on combustion of boron and boron-based fuel-rich propellants. J. Propul. Power. 1996;12:26–33. doi: 10.2514/3.23986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato R, Niwa Studies M. on nitrate reductase. VII. Reinvestigation on the identity of the enzyme with cytochrome b Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1952;25:202–210. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.25.202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sabatini JJ, et al. An Examination of Binder Systems and Their Influences on Burn Rates of High‐Nitrogen Containing Formulations. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 2011;36:145–150. doi: 10.1002/prep.201000061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabatini DJJ, Poret JC, Broad Boron RN. Carbide as a Barium‐Free Green Light Emitter and Burn‐Rate Modifier in Pyrotechnics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:4624–4626. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oranov AR, et al. Ionic high-pressure form of elemental boron. Nature. 2009;457:863–867. doi: 10.1038/nature07736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hooton JC, et al. Characterization of particle-interactions by atomic force microscopy: effect of contact area. Pharm. Res. 2003;20:508–514. doi: 10.1023/A:1022684911383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou W, et al. Persulfate salt as an oxidizer for biocidal energetic nano-thermites. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015;3:11838–11846. doi: 10.1039/C5TA00756A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agreda NJL. Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 2015;46:1376–1399. doi: 10.1007/s11663-015-0309-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moon MO, Kang BC, Lee SB, Boo JH. Temperature effect on structural properties of boron oxide thin films deposited by MOCVD method. Thin Solid Films. 2004;464:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.tsf.2004.05.107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torimoto T, et al. Ultrathin oxide shell coating of metal nanoparticles using ionic liquid/metal sputtering. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015;3:6177–6186. doi: 10.1039/C4TA06643J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shahedifar V. & A. M. Rezadoust Thermal and mechanical behavior of cotton/vinyl ester composites: Effects of some flame retardants and fiber treatment. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2013;32:681–688. doi: 10.1177/0731684413475911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yano Condensed Y. phase reaction of boron with potassium nitrate. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 1989;14:187–189. doi: 10.1002/prep.19890140503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sousa VC, Segadaes AM, Morelli MR, Kiminami RHGA. Combustion synthesized ZnO powders for varistor ceramics. Int. J. Inorg. Mater. 1999;1:235–241. doi: 10.1016/S1466-6049(99)00036-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miler HA, et al. Metastable nanostructured metallized fluoropolymer composites for energetics. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2013;1:7050–7058. doi: 10.1039/c3ta11603d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith MA, Glasser Spontaneous D. combustion of carbonaceous stockpiles. Part II. Factors affecting the rate of the low-temperature oxidation reaction Fuel. 2005;84:1161–1170. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoh JI, et al. Characterization of aluminized RDX for chemical propulsion. Int’l J. of Aeronautical & Space Sci. 2015;16:418–424. doi: 10.5139/IJASS.2015.16.3.418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kharatyan SL, et al. Effect of heating rate on kinetics of high‐temperature reactions: Mo‐Si system. AIChE J. 2005;51:261–270. doi: 10.1002/aic.10303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Connell PA, McKenna Arrhenius-type GB. temperature dependence of the segmental relaxation below Tg. J. Chem. Phys. 1999;110:11054–11060. doi: 10.1063/1.479046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yates K, McClelland RA. Mechanisms of ester hydrolysis in aqueous sulfuric acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:2686–2692. doi: 10.1021/ja00987a033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li C, Arai Y, Maruya KI, Onishi Physical T. Chemistry in Condensed Phases. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1989;1(85):929–943. doi: 10.1039/f19898500929. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He XH, Yan B. Double role of hydroxy group for water dispersibility and luminescence of REF 3 (RE=Yb, Er, Tm) based mesocrystals. New J. Chem. 2015;39:6730–6733. doi: 10.1039/C5NJ01355K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hasselman DPH, Johnson LF. Effective thermal conductivity of composites with interfacial thermal barrier resistance. J. Compos. Mater. 1987;21:508–515. doi: 10.1177/002199838702100602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu A, Zhang WX. Fine structural features of nanoscale zero-valent iron characterized by spherical aberration corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy (Cs-STEM) Analyst. 2014;139:4512–4518. doi: 10.1039/C4AN00679H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.