Over decades, the immunological research of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection has focused on HBV-specific T cells. In chimpanzees acutely infected with HBV, the deletion of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells causes chronic HBV infection. In humans, the HBV-specific T-cell response is temporally correlated with serum HBV clearance during an acute HBV infection, whereas HBV-specific T cells are both quantitatively and qualitatively defective in chronic HBV patients. These studies have suggested that the viral clearance predominately depends on the vigor and specificity of the T-cell responses, which are well summarized by a previous review.1 In contrast, humoral immunity, including B cells and anti-HBV antibody, which may also stop HBV infections, has largely been neglected. However, clinical practices have recently identified the potential importance of B-cell-mediated humoral immunity in the clearance or suppression of HBV infection. Emerging evidence has highlighted B-cell immune features2 and antibody-based prognosis3 and therapy4 in chronic HBV infection. However, many questions remain that prevent a clear understanding of the roles of humoral immunity and its protective mechanisms, which hold the key for their ultimate applications in curing chronic hepatitis B (CHB).

Key role of b-cell-based humoral immunity in the clearance of hbv infection

In general, by secreting neutralizing antibodies, B cells can limit viral infection and significantly contribute to viral elimination. Clinical practices have repeatedly shown that B-cell depletion with rituximab against CD20 was the riskiest factor for HBV reactivation among different immune-suppressive agents in lymphoma patients with previously controlled HBV;5 thus these findings indicate that an antibody to HBV is essential to maintain HBV under immune surveillance. An unexpected hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) clearance has also been frequently encountered after bone marrow transplantation from vaccinated donors to CHB recipients.6 For HBV-infected patients receiving liver transplantation, the adoptive anti-HBV immunity (likely both cellular and humoral immunity) from donors potentially clears the residual virus and protects the liver graft from HBV reinfection.7 Moreover, anti-HBsAg antibodies (HBsAb) recognize circulating HBsAg and clear infectious HBV particles in vivo, and the presence of HBsAb in serum is considered an indicator of the resolution of CHB. These data suggest that B-cell-based humoral immunity may act as a key element for long-term HBV control.

B Cells function in the liver pathogenesis of hbv infection

The potential importance of B cells in HBV infection may also lie in aspects other than antibody production. We comprehensively analyzed the dynamics of B cells in the natural history of HBV infection. B cells displayed a hyperactivation status in CHB patients as evidenced by increased CXC chemokine motif receptor 3, CD71 and CD69 expression and elevated plasma immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM levels.2 Gene expression profiling performed in HBV-infected patients with different clinical and virological profiles of diseases also identified a B-cell activation signature in patients with active hepatitis.8 Interestingly, antibody-secreting B cells and their antibodies (particularly for anti-HBcAg) may have an important role in the severity of CHB. Patients with HBV-associated acute liver failure were characterized by an overwhelming B-cell response apparently centered in the liver, with a massive accumulation of plasma cells secreting IgG and IgM, accompanied by complement deposition, with anti-HBcAg involved.9 In addition, B cells could act as antigen-presenting cells to shape T-cell immunity and have been shown to have a regulatory role during viral infections. For example, interleukin-10-producing B cells (regulatory B cells) were increased during hepatic flares in CHB patients and have been shown to modulate not only inflammatory events but also HBV-specific T-cell responses.10 These data suggest that humoral immunity may exert a primary role in HBV-associated pathogenesis and indicate potential immune-regulatory strategies targeting B cells for future studies.

Hbv-specific b cells in hbv infection

Owing to the lack of robust techniques to grow antigen-specific B cells in culture, knowledge regarding HBV-specific B cells during HBV infection at the clonal level is scarce. As reported for HBV-specific T cells, anti-HB producing B cells were more common in patients with acute hepatitis B than patients with CHB who generally lack HBsAg-specific B cells and HBsAb. The deficiency of HBsAg-specific B cells was considered to be responsible for the HBV persistence because their restoration was associated with HBsAg seroconversion in chronic HBV infection.2 Notably, intriguing data have indicated the presence of HBsAg/anti-HBs immune complexes in CHB patients, which has been suggested to prevent the detection of free anti-HB antibodies and indicate the persistence of anti-HB-producing B cells during CHB.11 In addition, the hardly detectable anti-HB-producing B cells in the periphery may not be equal to their absence in the body because memory B cells and plasma cells home to the inflamed sites and bone marrow. Further investigations are required to clarify these possibilities. In addition, studies that analyze the behavior of HBV-specific B cells and their derived antibodies during the natural course of HBV infection are warranted. Future investigations would substantially benefit from the rapidly evolving knowledge regarding HIV-1- and Flu-specific B cells, as well as newly emerging techniques, such as the fluorescent antigen probe and high-throughput single-cell sequencing.12

Antibody-mediated immune therapy in chb

Antibody immunotherapy is widely used to treat cancer, auto-immune diseases and acute/chronic viral infections. Anti-HBV antibodies, including anti-HBc, anti-HBe and anti-HBs, are useful serological markers, whereas only anti-HB antibodies are considered to be protective.13 Anti-HBsAg-specific antibodies have shown direct HBsAg suppression effects in clinical trial studies;14 however, the effects were only maintained for the short term. More potent antibodies with long-lasting HBsAg clearance effects are required for clinical application in CHB patients. Recently, several murine anti-HB monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were tested for their therapeutic effects in HBV mouse models.15 Interestingly, the anti-HBV effects did not correlate with the neutralizing activity of mAbs; the effects depended on their binding epitopes. In particular, mAb E6F6 treatment not only reduced the HBV and HBsAg load but also prompted T-cell responses in HBV transgenic mice, potentially through a non-neutralizing but novel Fcγ receptor-dependent phagocytosis mechanism.15 This antibody was subsequently modified with Fc engineering and evaluated for its pharmacokinetics in mice and nonhuman primates, thus demonstrating a significant increase in the serum half-life up to 300 h, which may substantially improve the clinical efficacy of the anti-HBV antibody.16

In addition to antibodies targeting HBsAg, such as E6F6, other potent mAbs targeting PreS1 epitopes are important. The mapping of HBV regions essential for infectivity points to the PreS1 domain and the antigenic loop region (also referred to as the ‘a-determinant’) of the HBV envelop protein.4 The PreS1 domain is responsible for HBV binding to its hepatic receptor Na+-taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide, whereas the antigenic loop interacts with heparin sulfate proteoglycans on hepatocytes, thus enriching HBV virions in the perisinusoidal space. Antibodies against these two regions are capable of neutralizing HBV infection.4 Both the hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) in clinical practice and the protective antibodies induced by the current prophylactic HBV-vaccines recognize the ‘a-determinant’ region.4 Although hepatitis B immune globulin has been widely applied to prevent HBV transmission in transplantation and mother-to-infant transmission settings, the contribution of antibodies in the control of CHB has not previously been proven.14 Regarding the PreS1 antigen and anti-PreS1, a recent study indicated that anti-PreS1 was present in many CHB patients, and the PreS1 domain was a weak point in HBsAg-induced immune tolerance.17 A high level of HBsAg may induce immune tolerance, which is difficult to break. However, PreS1 represents <0.1% of total HBV antigens and is weak to induce tolerance. PreS1 as a vaccine has been shown to generate anti-PreS1, which depletes infectious particles as the HBV virions contain PreS1. Intriguingly, the PreS1 vaccine also reduces the HBsAg level and induces robust immune responses, even to HBsAg, in HBV-tolerized mice.17 The third generation of HBV vaccines, which contain the PreS1/S2 region and small HBsAg, have been approved and have recently been shown to be more potent than the second-generation vaccine, which only contained small HBsAg without the PreS1/S2 region.18 Certainly, the PreS1 and anti-PreS1 levels should be assessed in additional clinical cohorts to assess the diagnostic and prognostic potentials. PreS1 containing vaccines in both prophylactic and therapeutic applications should also be assessed to confirm their efficacy. The therapeutic effects of different human-derived anti-HBV mAb cocktails in CHB patients are expected in the future; however, several challenges should be overcome before their final clinical applications.4

The predictive value of anti-hbv ab

Virus-related biomarkers have been tied to the efficacy of antiviral treatment in CHB patients, such as pretreatment HBV DNA, quantitative HBsAg and HBeAg and the recently identified HBcrAg and HBV pgRNA, which have served as predictors related to the outcome of interferon or nucleos(t)ide analog treatment.19 However, CHB-associated liver diseases involve virus–host interactions, and the treatment outcome is, to some extent, determined by the immune status of the host. It is reasonable that immunological factors are related to antiviral efficacy in some cases. In this aspect, the occurrence of anti-HBV antibodies, including HBsAb, HBeAb and HBcAb, represents the classical serological markers for screening or diagnosis of HBV infection.13 Moreover, a recent study proposed that higher anti-HBcAg levels may reflect a stronger host-adaptive anti-HBV immunity and may thus predict a better outcome after antiviral therapy, which was further confirmed in larger well-controlled prospective studies that comprised patients treated with interferons or nucleos(t)ide analogs.3 In addition, anti-PreS1 is a potential marker for the prediction of HBV infection outcome. In the clinic, anti-PreS1 appears early in the course of AHB. The occasional appearance of anti-PreS1 in several patients with chronic aggressive hepatitis or treated with antiviral agents correlated well with clinical improvement.20 However, the nature and clinical significance of anti-PreS1 in CHB have not been conclusive for the correlation between its changes in immune status and viral persistence.

Prospective

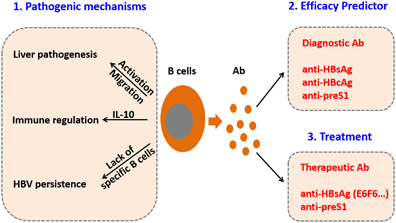

For decades, studies have been centralized in anti-HBV cellular immunity, which was thought to have the capacity to control HBV replication. Therapeutically, boosting the defective HBV-specific T cells using checkpoint inhibitors or therapeutic vaccines and adoptively transferring engineered HBV-specific T cells were generally considered to increase HBV-specific T-cell responses in CHB patients. However, current trials with checkpoint inhibitors (such as anti-PD1/PDL-1 blockade) or HBV therapeutic vaccines have only shown suboptimal and limited efficacy. Engineered anti-HBV T cells with conventional T-cell receptors or chimeric antigen receptors have also been proposed and constructed; however, the technology of producing a substantial quantity of engineered T cells remains cumbersome, and the potential side effect is concerning, thus restricting its translation in broad clinical practice. Currently, humoral immunity is entering the central stage, and B cells and antibodies have been related to the pathogenesis, efficacy predictor and novel treatment during HBV infection (Figure 1). In this regard, it is interesting to identify a close analogy between HBV and HIV-1 infection. Both viruses are characterized by retro-transcriptional processes, which may be effectively inhibited by nucleos(t)ide analog treatments; however, they failed to achieve a functional cure as a result of the presence of integrated HIV-1 pro-viral DNA and the intrahepatic HBV covalently closed circular DNA. Host immunity is predicted to have important roles in controlling both HBV and HIV-1 activity. In particular, broadly neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1 have been discovered and have shown promising therapeutic effects, thus restoring the research interest in humoral immunity. Following this analogy, we suggest that it is the right time to re-include humoral immunity in the focus of HBV infection research, particularly for HBV-specific B cells, antibody-based diagnostic markers and antibody therapy.

Figure 1.

Emerging aspects of humoral immunity in HBV infection. Based on recent findings, host humoral immunity has an important role in liver pathogenesis during HBV infection and may be applied in anti-HBV efficacy prediction and antibody-based treatment. Future studies are required to thoroughly elucidate the underlying mechanisms of humoral immunity-mediated liver pathogenesis and thus develop more efficient prognostic approaches, vaccines and therapies for hepatitis B. HBV, hepatitis B virus.

Thus we suggest that the combination of both anti-HBV cellular and humoral interventions will form the most effective immunotherapy for CHB patients in the future. Although the humoral immune response alone cannot eliminate an intracellular virus and HBV-infected hepatocytes, which could be targeted by T cells, the long-term suppression of HBV activity and functional cure of CHB will not succeed without concomitant functional restoration of anti-HBV humoral immunity.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Yang-Xin Fu for his critical review of the manuscript. This study was supported, in part, by grants from the National Science Fund for Outstanding Young Scholars (81222024 to ZZ).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Rehermann B, Nascimbeni M. Immunology of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:215–229. doi: 10.1038/nri1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu X, Shang Q, Chen X, Nie W, Zou Z, Huang A, et al. Reversal of B-cell hyperactivation and functional impairment is associated with HBsAg seroconversion in chronic hepatitis B patients. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015;12:309–316. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan R, Sun J, Yuan Q, Xie Q, Bai X, Ning Q, et al. Baseline quantitative hepatitis B core antibody titre alone strongly predicts HBeAg seroconversion across chronic hepatitis B patients treated with peginterferon or nucleos(t)ide analogues. Gut. 2016;65:313–320. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao Y, Zhang TY, Yuan Q, Xia NS. Antibody-mediated immunotherapy against chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13:1768–1773. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1319021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loomba R, Liang TJ. Hepatitis B reactivation associated with immune suppressive and biological modifier therapies: current concepts, management strategies, and future directions. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1297–1309. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindemann M, Koldehoff M, Fiedler M, Schumann A, Ottinger HD, Heinemann FM, et al. Control of hepatitis B virus infection in hematopoietic stem cell recipients after receiving grafts from vaccinated donors. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:428–431. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schumann A, Lindemann M, Valentin-Gamazo C, Lu M, Elmaagacli A, Dahmen U, et al. Adoptive immune transfer of hepatitis B virus specific immunity from immunized living liver donors to liver recipients. Transplantation. 2009;87:103–111. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31818bfc85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanwolleghem T, Hou J, van Oord G, Andeweg AC, Osterhaus AD, Pas SD, et al. Re-evaluation of hepatitis B virus clinical phases by systems biology identifies unappreciated roles for the innate immune response and B cells. Hepatology. 2015;62:87–100. doi: 10.1002/hep.27805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farci P, Diaz G, Chen Z, Govindarajan S, Tice A, Agulto L, et al. B cell gene signature with massive intrahepatic production of antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen in hepatitis B virus-associated acute liver failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8766–8771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003854107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das A, Ellis G, Pallant C, Lopes AR, Khanna P, Peppa D, et al. IL-10-producing regulatory B cells in the pathogenesis of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Immunol. 2012;189:3925–3935. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang JM, Xu Y, Wang XY, Yin YK, Wu XH, Weng XH, et al. Coexistence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and heterologous subtype-specific antibodies to HBsAg among patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1161–1169. doi: 10.1086/513200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hofmann D, Lai JR. Exploring human antimicrobial antibody responses on a single B cell level. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2017; 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009;373:582–592. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galun E, Eren R, Safadi R, Ashour Y, Terrault N, Keeffe EB, et al. Clinical evaluation (phase I) of a combination of two human monoclonal antibodies to HBV: safety and antiviral properties. Hepatology. 2002;35:673–679. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang TY, Yuan Q, Zhao JH, Zhang YL, Yuan LZ, Lan Y, et al. Prolonged suppression of HBV in mice by a novel antibody that targets a unique epitope on hepatitis B surface antigen. Gut. 2016;65:658–671. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang C, Xia L, Chen Y, Zhang T, Wang Y, Zhou B et al. A novel therapeutic anti-HBV antibody with increased binding to human FcRn improves in vivo PK in mice and monkeys. Protein Cell 2017; epub ahead of print 4 July 2017; doi: 10.1007/s13238-017-0438-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Bian Y, Zhang Z, Sun Z, Zhao J, Zhu D, Wang Y, et al. Vaccines targeting preS1 domain overcome immune tolerance in hepatitis B virus carrier mice. Hepatology. 2017;66:1067–1082. doi: 10.1002/hep.29239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shouval D, Roggendorf H, Roggendorf M. Enhanced immune response to hepatitis B vaccination through immunization with a Pre-S1/Pre-S2/S vaccine. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2015;204:57–68. doi: 10.1007/s00430-014-0374-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Block TM, Locarnini S, McMahon BJ, Rehermann B, Peters MG. Use of current and new endpoints in the evaluation of experimental hepatitis B therapeutics. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:1283–1288. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hellstrom U, Lindh M, Krogsgaard K, Sylvan S. Demonstration of an association between detection of IgG antibody reactivity towards the C-terminal region of the preS1 protein of hepatitis B virus and the capacity to respond to interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis B. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:804–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]