Dear Editor,

Histone modifications regulate many fundamental biological processes, including DNA replication, transcription, and repair. Eighteen posttranslational modifications of histones, including acetylation, succinylation, and methylation, have been reported1–3. Lysine acetyltransferase 2A (KAT2A, also known as GCN5), a member of the GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase superfamily and a component of Spt-Ada-KAT2A-acetyltransferase (SAGA) and Ada-two-A-containing complexes, was identified as the first transcription-related histone acetyltransferase in 19964,5. KAT2A binds to acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) and transfers its acetyl group to histones to regulate chromatin architecture and locus-specific transcription6.

Our recent studies reported that KAT2A can also function as a histone succinyltransferase by directly transferring the succinyl group from succinyl-CoA to histone H3 lysine 79 (H3K79), which is important for the regulation of gene expression in tumor cells7. To elucidate the catalytic mechanism, we determined the structures of both the apo and succinyl-CoA-complexed KAT2A using X-ray crystallography7. By comparing these structures with that of KAT2A in complex with acetyl-CoA7, we previously demonstrated that succinyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA occupy similar binding sites in the catalytic domain of KAT2A and identified key residues interacting with the acyl chains7. In the present work, we report a novel high-order assembly for the catalytic domain of KAT2A observed in the crystal structures of both the apo and succinyl-CoA complexes. It is important to note that both crystals were grown under conditions (pH of 4.6) different from the previously reported crystallization condition (pH of 7.0) of a monomer of the catalytic domain of KAT2A8.

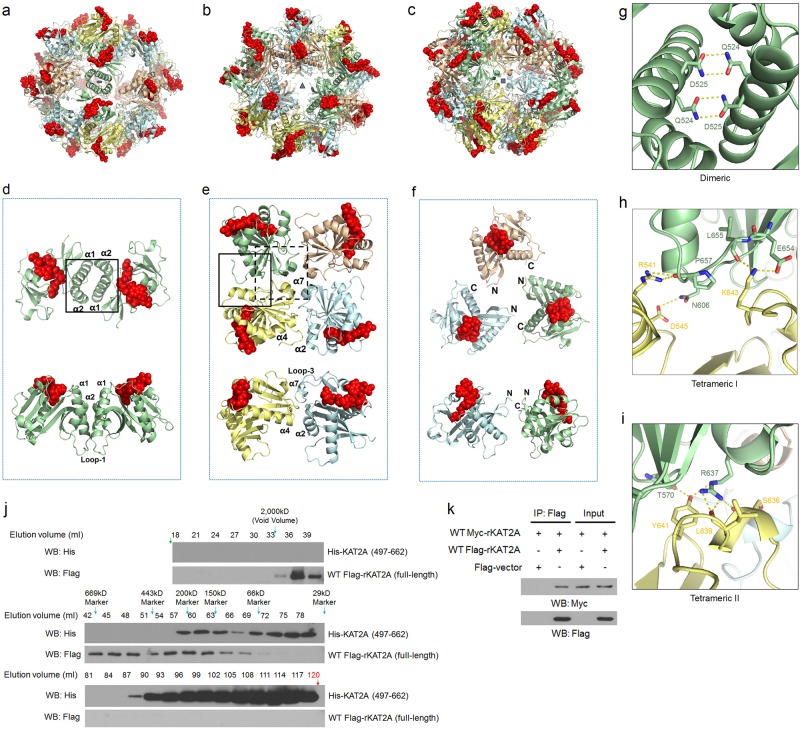

Although apo and succinyl-CoA-complexed KAT2A were crystallized in different space groups with different crystal packing contacts (i.e., P41212 vs. P213), the same octahedral supramolecular assembly was observed in both crystals: 24 KAT2A molecules formed a spherically shaped complex with a hollow center (Fig. 1a–c). Octahedral assemblies are characterized by 4-fold, 3-fold, and 2-fold symmetry axes. With these symmetry operations, an assembly of 24 molecules is generated from a single protein protomer. In the crystal of apo-KAT2A (i.e., space group P41212), 24 molecules in each crystallographic asymmetric unit gave rise to a complete octahedral assembly. The crystal of succinyl-CoA-complexed KAT2A had the space group of P213 with eight molecules in each asymmetric unit, but 24 molecules from three asymmetric units made a complete octahedron of the KAT2A–succinyl CoA complex (Fig. 1a–c).

Fig. 1. The high-order assembly of KAT2A in complex with succinyl-CoA.

a–c Octahedral complex of KAT2A in association with succinyl-CoA. The protein molecules are shown as ribbons, whereas the substrate succinyl-CoA molecules are shown in red as space-filling models. The complex is viewed along a 2-fold, b 3-fold, and c 4-fold symmetry axes. d–f Three different KAT2A oligomers found in the octahedral assembly. A dimer (d), tetramer (e), and trimer (f) are shown. The upper panels in these three figures represent top views along the symmetry axes from the outside of the octahedron. The lower panels are views from the side, with the molecules at the back removed for clarity. Secondary structure elements at the oligomer interfaces are labeled. g–i Hydrogen bonds and salt bridges at the dimeric (g) and tetrameric (h, i) interfaces. The protein molecules are shown as ribbons, whereas the interacting residues are labeled and shown as sticks. The molecular regions shown in g, h, and i correspond to the rectangle box highlighted in d, solid rectangle box in e, and dashed rectangle box in e. j Gel-filtration analyses of purified recombinant His-KAT2A (497–662) (upper panel) and wild-type (WT) Flag-rKAT2A (full-length) in the nucleus of 293T cells (lower panel). Bacterially purified His-KAT2A (497–662) or the nuclear lysate from WT Flag-rKAT2A (full-length)-expressing 293T cells was injected into an AKTA Purifier system with a HiPrep 16/60 Sephacryl S-300 High Resolution column for molecular weight-dependent fractionation. The elution from 18 ml to 120 ml was collected with 3 ml for each fraction. Immunoblot analysis of each fraction was performed with the indicated antibodies. The elution volume for each molecular weight marker is indicated. A second peak of His-tagged catalytic domain of KAT2A near 110 ml was observed; this was likely due to the nonspecific interaction of the catalytic domain of KAT2A with the resin. The same peak was not affected by increasing the NaCl concentration from 0.15 M to 0.5 M. k WT Myc-rKAT2A was co-transfected with WT Flag-rKAT2A or a control vector into U251 glioblastoma cells. Immunoprecipitation was performed with an anti-Flag antibody. Immunoblot analysis was performed with the indicated antibodies

The stability of a protein–protein interaction usually correlates with the amount of buried surface areas. Based on results from an interface analysis performed by the program PISA9, we found that the formation of the KAT2A octahedron structure was mediated by strong interactions at both dimer and tetramer interfaces, with total buried surface areas of 1400 Å2 and 1300 Å2, respectively (Fig. 1d–f; Supplementary Table S1). At the dimer interface, helices α1 and α2 from one subunit were in close contact with the same two helices from a neighboring subunit (Fig. 1d). The formation of tetramers in the octahedron was largely mediated by α2, α7, and loop 3 of one molecule interacting with α4 and the C-terminal tail of an adjacent molecule (Fig. 1e). Interactions of KAT2A around the three-fold symmetry axis were weak; the buried surface area was less than 10 Å2 (Fig. 1f), suggesting that tetramers or dimers may act as precursors for octahedron assembly. Interactions at the dimer interface were mostly hydrophobic in nature, except for two pairs of hydrogen bonds mediated by Q524 and D525 (Fig. 1g). In comparison, more polar interactions were observed at the tetrameric interface, including a salt bridge mediated by E654 and K643, as well as hydrogen bonds mediated by the side chains of R541, D545, R637, and Y641 (Fig. 1h, i).

To determine the physiological relevance of the octahedral structure of KAT2A, we employed gel-filtration analyses and identified high-molecular weight complexes of the purified catalytic domain of KAT2A, ranging from ~29 kD to the fractions that correspond to the molecular weight larger than 200 kD (Fig. 1j). Full-length KAT2A isolated from nuclear fractions of 293T cells gave rise to even larger complexes, with an estimated molecular weight of 94kD, up to a maximal detectable molecular weight (≥2000 kD; Fig. 1j). The wide range of molecular weight distributions may include assembly intermediates expected for an octahedral supramolecular complex. Additionally, immunoprecipitation analysis of cells expressing both full-length Flag-tagged KAT2A and full-length Myc-tagged KAT2A confirmed interaction between individual KAT2A proteins (Fig. 1k), further supporting the notion that KAT2A forms high-order assemblies in cells.

Close inspection of the crystal structure of the catalytic domain of KAT2A indicated that both N- and C-termini are exposed on the outer surface of the octahedron (Supplementary Fig. S1). Therefore, other components of the catalytic complex (i.e., the PCAF-HD and bromodomain of KAT2A) may connect to the catalytic domain of KAT2A and may be situated on the surface of the octahedron without disturbing its overall structural organization. Furthermore, all 24 substrate-binding pockets in the octahedron structure are exposed externally (Fig. 1d–f). Thus, rapid diffusion of either acetyl-CoA or succinyl-CoA in and out of the KAT2A active site is possible during catalysis.

Although yet to be reported for any histone acetyltransferases, supramolecular assemblies of enzymes frequently form and are considered advantageous in capturing substrates10. Similarly, the formation of a spherically shaped supramolecular complex with 24 catalytic domains of KAT2A is likely to play such a role. The α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (α-KGDH) complex binds to KAT2A in the nucleus and facilitates KAT2A’s succinyltransferase activity by providing local succinyl-CoA, which can overcome the disadvantage of limited succinyl-CoA concentration in the nucleus7. With an octahedral assembly of the KAT2A:α-KGDH complex, the substrate-binding site of KAT2A is greatly enriched, thus further facilitating the capture of α-KGDH-produced succinyl-CoA by KAT2A to ensure efficient H3K79 succinylation in vivo. Thus, the supramolecular assemblies of the catalytic domain of KAT2A, high local concentrations of succinyl-CoA generated by the KAT2A-associated α-KGDH complex, and high catalytic activity of KAT2A toward succinyl-CoA7 should help compensate for the relatively low nuclear concentration of succinyl-CoA to promote KAT2A-mediated histone succinylation.

Together, our recent publication7 and these new structural results for the first time identified a histone succinyltransferase, KAT2A, which was known as a histone acetyltransferase. In addition, we unearthed an important mechanism of histone H3 succinylation, in which KAT2A uses succinyl-CoA locally generated by α-KGDH in the same supramolecular complex to posttranslationally modify histone H3 for gene transcription. Our findings highlight the significance of the metabolic enzyme α-KGDH-coupled KAT2A complex in the regulation of gene expression, tumor cell proliferation, and tumor formation.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Li Li at The University of Texas Health Science at Houston for technical support and Erica Goodoff for critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant R01 NS089754 (to Z.L.), NCI grant 1R01 CA204996 (to Z.L.), the NIH/NCI P30 CA016672 (to Z.L.), Welch Foundation grant C-1565 (to Y.J.Y.), and the 2018 UT Proteomics Network Pilot Fund (to Y.W.). Z.L. is a Ruby E. Rutherford Distinguished Professor.

Authors’ contributions

Z.L., Y.T., D.X., Y.R.G., and Y.W. conceived and designed the study and wrote the manuscript. Y.W. and Y.R.G. performed the experiments.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Yizhi Jane Tao, Email: ytao@rice.edu.

Zhimin Lu, Email: zhiminlu@mdanderson.org.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper at (10.1038/s41421-018-0048-8).

References

- 1.Tan M, et al. Identification of 67 histone marks and histone lysine crotonylation as a new type of histone modification. Cell. 2011;146:1016–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang H, Sabari BR, Garcia BA, Allis CD, Zhao Y. SnapShot: histone modifications. Cell. 2014;159:458–458.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tessarz P, Kouzarides T. Histone core modifications regulating nucleosome structure and dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:703–708. doi: 10.1038/nrm3890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brownell JE, et al. Tetrahymena histone acetyltransferase A: a homolog to yeast Gcn5p linking histone acetylation to gene activation. Cell. 1996;84:843–851. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant PA, et al. Yeast Gcn5 functions in two multisubunit complexes to acetylate nucleosomal histones: characterization of an Ada complex and the SAGA (Spt/Ada) complex. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1640–1650. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.13.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin Y, Fletcher CM, Zhou J, Allis CD, Wagner G. Solution structure of the catalytic domain of GCN5 histone acetyltransferase bound to coenzyme A. Nature. 1999;400:86–89. doi: 10.1038/22343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, et al. KAT2A coupled with the alpha-KGDH complex acts as a histone H3 succinyltransferase. Nature. 2017;552:273–277. doi: 10.1038/nature25003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuetz A, et al. Crystal structure of a binary complex between human GCN5 histone acetyltransferase domain and acetyl coenzyme A. Proteins. 2007;68:403–407. doi: 10.1002/prot.21407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Persson K, Schneider G, Jordan DB, Viitanen PV, Sandalova T. Crystal structure analysis of a pentameric fungal and an icosahedral plant lumazine synthase reveals the structural basis for differences in assembly. Protein Sci. 1999;8:2355–2365. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.11.2355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.