Abstract

Immunological tolerance loss is fundamental to the development of autoimmunity; however, the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. Immune tolerance consists of central and peripheral tolerance. Central tolerance, which occurs in the thymus for T cells and bone marrow for B cells, is the primary way that the immune system discriminates self from non-self. Peripheral tolerance, which occurs in tissues and lymph nodes after lymphocyte maturation, controls self-reactive immune cells and prevents over-reactive immune responses to various environment factors. Loss of tolerance results in autoimmune disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), type 1 diabetes (T1D) and primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC). The etiology and pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases are highly complicated. Both genetic predisposition and epigenetic modifications are implicated in the loss of tolerance and autoimmunity. In this review, we will discuss the genetic and epigenetic influences on tolerance breakdown in autoimmunity. Genetic and epigenetic influences on autoimmune diseases, such as SLE, RA, T1D and PBC, will also be briefly discussed.

Introduction

Immune tolerance refers to unresponsiveness of the immune system toward certain substances or tissues that are normally capable of stimulating an immune response. Self-tolerance is essential for normal immune balance, and failure or breakdown of that tolerance results in autoimmunity and autoimmune diseases.

Autoimmune diseases are a group of >80 chronic, relapsing, and sometimes lethal diseases, characterized by a defective immune system resulting in the loss of tolerance to self-antigens and over-expression of autoantibodies. More importantly, autoimmune disorders often occur during reproductive years, which may lead to pregnancy loss and infertility.1 Although great progress has been made, particularly new gene loci discoveries with the advent of genome-wide association studies, the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases remains elusive. The origins of autoimmune diseases cannot be explained by genetic factors alone because the occurrence of autoimmune diseases in identical twins is not always consistent.2 Subsequent studies imply that epigenetic modifications also participate in the loss of immune tolerance and autoimmunity in genetically predisposed individuals.3

This article will review the current status of genetic and epigenetic contributions to the loss of immune tolerance in autoimmunity. Genetic and epigenetic influences on autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), type 1 diabetes (T1D) and primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), will also be briefly discussed.

Loss of tolerance and autoimmunity

The immune system is responsible for identifying and executing proper responses to eliminate non self-antigens and prevent the harmful response to self-antigens, referred to as immune tolerance.4 To maintain immune homeostasis in balance, the individual must be tolerant of their own potentially antigenic substances. Once self-tolerance is disrupted, autoimmunity will arise.

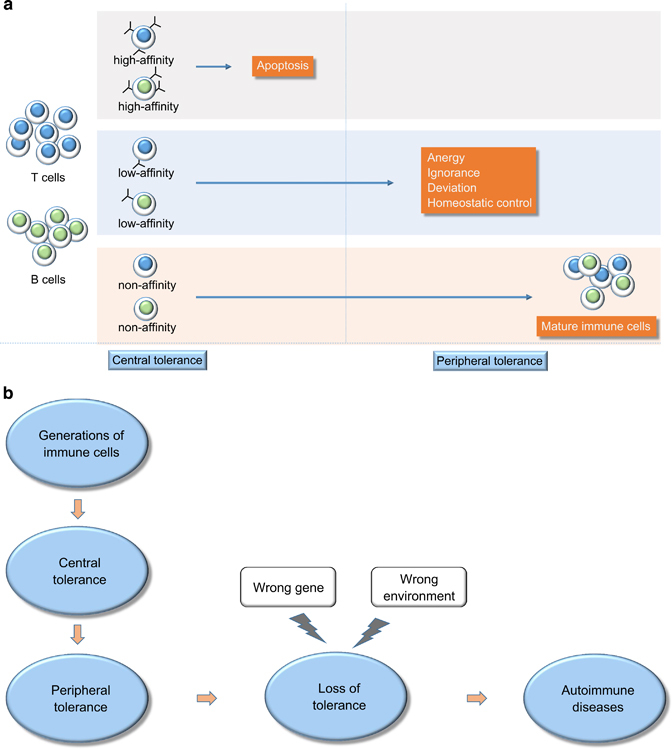

Based on where the state is originally induced, self-tolerance can be classified into two types: central and peripheral tolerance (Figure 1a). Central tolerance refers to eliminations of autoreactive lymphocyte clones before they become fully immunocompetent, of which the main mechanism is negative selection. This procedure occurs in the stage of lymphocyte development in the thymus and bone marrow for T and B lymphocytes, respectively. After T and B lymphocytes enter the peripheral tissues and lymph nodes, peripheral tolerance will occur to inhibit immune responses against the body's own tissues, which occurs primarily in the secondary lymphoid organs, such as spleens and lymph nodes. Mechanisms of peripheral tolerance include anergy (functional unresponsiveness), deletion (apoptotic cell death) and suppression by regulatory T cells.5 As stated above, the tolerance is processed on two ‘levels’, in which the ‘lower level’ of peripheral tolerance functions as a back-up strategy of the ‘upper level’ of central tolerance. Autoimmune diseases may develop when self-reactive lymphocytes escape from tolerance and are thereby activated. However, the underlying exact mechanisms are not entirely known. Current knowledge suggests that autoimmunity stems from a combination of genetic variants and various acquired environmental triggers. Figure 1b illustrates the loss of tolerance and autoimmune diseases.

Figure 1.

(a) Central and peripheral tolerance. In the thymus, T cells with high affinity for self-antigens undergo apoptosis, while B cells undergo a similar process in the bone marrow. Low- and non-affinity T and B cells enter peripheral tissues and lymph nodes, where non-affinity T and B cells mature into immune cells and low-affinity T and B cells are deleted by many mechanisms, such as anergy, ignorance, deviation and homeostatic control. (b) The process of loss of tolerance to autoimmune diseases. Immune cells generate and experience central and peripheral tolerance. Tolerance fails because of the interaction of the wrong environment with the wrong gene, resulting in autoimmune disease.

Genetic influences in the tolerance breakdown in autoimmunity

The loss of tolerance is a complex process that poses a great challenge to investigate. Recent studies on monogenic forms of autoimmune diseases advance our understanding of the loss of tolerance (Table 1).6

Table 1.

Genes related to loss of tolerance in autoimmunity

| Gene | Autoimmune disease | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIRE | APS-1 | Downregulates self-antigens in the thymus, resulting in defective negative selection of self-reactive T cells | 7, 8 |

| Foxp3 | IPEX | suppresses CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells | 13 |

| CTLA4 | Graves’ disease type 1 diabetes | Inhibits T cell responses and promotes long-lived anergy | 15 |

| FAS | ALPS | Failure of apoptotic death of self-reactive B and T cells | 17 |

AIRE and central tolerance

The transcription factor autoimmune regulator (AIRE) was originally identified as the mutated gene in patients with an autosomal recessive form of autoimmunity called autoimmune polyglandular syndrome Type 1 (APS1), featured by autoimmune attacks against multiple endocrine organs, skin and other tissues.7,8 When the gene AIRE was knocked out in mice, the thymic expression of some antigens that are normally expressed at high levels in different peripheral tissues is influenced. Therefore, T cells specific for these antigens will escape from negative selection (central tolerance), entering the periphery and initiating damage to the self.9

Foxp3 and Treg cells in autoimmune diseases

Either protective or harmful immune responses are mainly regulated by T and B cells; however, firm evidence shows that the normal immune system also produces a sub-population of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells, namely Treg cells. Treg cells function to suppress the immune responses, and a deficiency of Treg cells is responsible for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Treg cells specifically express the transcription factor Foxp3 (forkhead box P3), which is a key regulator of Treg cell development and function. Because of the absence of Treg cells, induced knockout or spontaneous mutation of the Foxp3 gene in mice results in a systemic autoimmune disease.10,11,12 Correspondingly, in humans, the Foxp3 gene mutation also leads to a genetic disease called immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked syndrome (IPEX syndrome), demonstrating the importance of Foxp3 in the immune system.13

CTLA4 in T cell anergy

As an inhibitory receptor, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4; CD152) is expressed by T cells and interacts with the costimulatory molecules B7-1 (CD80) and B7-2 (CD86) and is capable of inhibiting T-cell responses and promoting long-lived anergy.14 Knockout of germline CTLA4 in mice represents a fatal syndrome with lymphocyte infiltration of multiple organs and severe enlargement of lymphoid organs.15 Several autoimmune diseases, such as type 1 diabetes and Graves’ diseases, are demonstrated to be associated with CTLA4, although the exact function has not been defined.16

FAS and lymphocyte apoptosis

Fas (CD95), the prototype of a death receptor of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor family, plays a role in the deletion of mature T and B cells that recognize self antigens.17 The Fas ligand binding with its receptor induces apoptosis. Fas ligand/receptor interactions play a critical role in the process of the immune system. For example, activated T cells express the Fas ligand. During clonal expansion, activated T cells are initially resistant to Fas-mediated apoptosis and will become progressively sensitive, ultimately leading to activation-induced cell death (AICD). This process is vital to prevent an excessive immune response and eliminate autoreactive T cells. Mutations of Fas will lead to a childhood disorder of apoptosis called autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS).18

Epigenetic influence on T and B lymphocyte tolerance to self

Genetic background is essential to understand the onset of diseases, but it is insufficient for the full explanation. The incomplete concordance rates of autoimmune diseases in monozygotic twins also strongly suggest that other factors, such as environmental triggers, are involved in the pathogenesis of autoimmunity. Epigenetics refers to heritable genomic expression without alterations in the original DNA sequence, consisting of DNA methylation, histone modifications and microRNA (miRNA) regulations. Studies show that DNA methylation and the post-translational modification of histones are potentially responsible for the breakdown of immune tolerance and autoimmune disorders.

T and B lymphocytes are key players for immune responses, and during the T and B lymphocyte differentiation process, the regulation of each progression step is influenced by a potent network of transcription factors specific for each particular cellular state. Recent studies indicate that both T and B lymphocyte development are under epigenetic regulations.

DNA methylation

In naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, DNA hypermethylation in the promoter of IL-2 and IFN-γ was identified, suggesting that the defect in IL-2 and IFN- γ production is independent of clonal selection.19 Similarly, CpG residues at the IL-2 promoter and enhancer are also methylated in tolerant T cells.20 The loss of DNA methyltransferase Dnmt1 results in the over-production of IL-2, Th1 and Th2 cytokines.21

During the process from lymphoid progenitors to the B cell lineage, transcription factors EBF and E2A contribute to the DNA demethylation and nucleosomal remodeling of the CD79a promoter, which is necessary for its transcriptional activation by Pax5 and is essential to the formation of pro-B cells.22

Histone modifications

Compared to naive T cells, when activated T cells were restimulated under anergic conditions, increased histone deacetylation was observed at the IL-2 promoter, which was associated with enhanced recruitment of HDAC1 and HDAC2.23 Hypoacetylation at the IL-2 locus in anergic CD4+ T cells is caused by increased deacetylation and intact acetylation. The IFN-γ locus in anergic T cells is also hypoacetylated, resulting in a significant reduction of IFN-γ.24,25 Therefore, histone hypoacetylation at the IFN-γ and IL-2 gene loci function to sustain the closed chromatin structures and thus suppress transcriptional activities.

Unlike histone acetylation, histone methylation is more specific and complicated. For example, histone H3 trimethylation at lysine 27 (H3K27me3) is related to repressive chromatins whereas H3K4me3 is generally associated with permissive chromatins. In Th1 cells, H3K4me3 specifically marks IFN-γ and T-bet gene loci, whereas IL-4 and Gata-3 loci are imprinted with H3K27me3.26

During the stage from the pre–pro-B cell to pro-B cell, E2A-associated genes, such as EBF and FOXO1, are modified by H3K4me, a mark of gene enhancer elements. The activation of EBF and FOXO1 will lead to histone modifications of H3K4me3 on Pax5.27

MicroRNAs

During B-cell development and differentiation, miR-181, miR-150, and miR34a help target and repress transcripts critical for genes involved in B-cell generation. Genome-wide miRNA scans during lymphopoiesis lead to the identification of miRNAs that are primed for expression at different stages of differentiation, including the repressive mark H3K27me3 associated with gene silencing of lineage-inappropriate miRNA and the presence of the epigenetically active mark H3K4me. During B cell lineage specification, miR-320, miR-191, miR-139 and miR28 act as potential regulators of B-cell progression.28

Genetic and epigenetic influences in autoimmune diseases

As stated above, both genetic and epigenetic factors play indispensable roles in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases, most of which have unknown etiology. Genetic background is a source of susceptibility for disease onset, but it is insufficient for disease development. Recent genome-wide association studies confirmed the strong genetic background for immune-related diseases, but they fail to illustrate the mechanisms underlying immune tolerance breakdown explained by genetic aspects alone.29 Environmental factors, such as ultraviolet rays, infections, nutrition and chemicals, also participate in the pathogenesis of autoimmunity.30 The advent of epigenetic research creates a bridge over genetics and the environment, providing a novel perspective to interpret these complex diseases. Tables 2 and 3 list epigenetic and genetic changes in autoimmune diseases.

Table 2.

Epigenetic modifications in autoimmune diseases

| Diseases | Epigenetic modifications | Influence | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| SLE | Hypomethylation of CD11a (ITGAL), CD40L (TNFSF5) and CD70 (TNFSF7) | Contributes to the overexpression of CD11a, CD40L and CD70 | 31, 32, 33 |

| Hypomethylation of IL-4 and IL-6 | Increases IL-4 and -6mRNA transcriptions | 34 | |

| Hypomethylation of Foxp3 | Induction of Foxp3 expression | 35 | |

| H3 and H4 acetylation and H3K4 dimethylation of TNFSF7 | Increases CD70 expression on T cells | 36 | |

| deacetylation of histone H3K18 of CREMα | silences IL2 gene expression | 37 | |

| Increased miR-21, miR-126 and miR148a | Inhibits DNMT1 expression | 38, 39 | |

| Increased miR-142 and miR-31 | Inhibits IL-4, IL-10, CD40L and ICOS expression and stimulates IL-2 production | 40 | |

| Overexpression of miR-30a | Reduction of Lyn | 41 | |

| RA | Demethylation of the IL-6 promoter in PBMCs | Overexpression of IL-6 in serum, synovial tissue, and synovial fluid | 42 |

| Hypomethylation of CXCL12 in synovial fibroblasts | Promotes matrix metalloproteinases and joint destruction | 43 | |

| Increased H3K4me3 in MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-9 and MMP-13 and decreased H3K27me3 in MMP-1 and MMP-9 | Regulates the transcription of MMPs in synovial fibroblasts | 44 | |

| Increased histone acetylation of MMP-1 and IL-6 | Up-regulates MMP-1 and IL-6 in synovial fibroblasts | 45, 46 | |

| Overexpressed miRNA-155 and 146a in synovial fibroblasts | miRNA-155 targets PU.1 and inhibits its expression; miRNA-146a targets IRAK1 and TRAF6 and suppresses their expression | 47 | |

| Decreased miRNA-124a | Targets MCP1 and CDK2 and increases their expression | 48 | |

| Increased miRNA-223 | Suppresses IGF-1R-mediated IL-10 | 49 | |

| T1D | Increased global DNA methylation level in LADA | Accompanied by upregulated expression level of DNMT3b | 50 |

| Hypermethylation of UNC13B | Indicated with the risk of diabetic nephropathy in T1D | 51 | |

| Genome-wide histone H3K9me2 in peripheral lymphocytes and monocytes | Increase in methylation level in H3K9me2 in several high-risk genes for T1D including the CTLA4 gene | 52 | |

| Increased miR-326 in PBMCs | Positively correlated with disease severity | 53 | |

| Downregulated miR-146 | Upregulates the expressions of TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), B-cell CLL/lymphoma 11A (BCL11A), syntaxin 3 (STX3) and numb homolog (NUMB) | 54 | |

| PBC | Hypermethylation of ATP12A, ATP5A1 and HOXD4 | Involved in ion channel transport and transport of bile salts | 55 |

| DNA demethylation of CD40L | Inversely correlated with IgM serum level | 56 | |

| Upregulated histone H4 acetylation in the promoter regions CD40L, LIGHT, IL17 and IFNG | Increased expression of these genes | 57 | |

| Downregulated histone H4 acetylation in the promoter regions of TRAIL, Apo2 and HDAC7A | Decreased expression of these genes | 57 | |

| Downregulation of miR-122a and miR-26a and increased expression of miR-328 and miR-299-5p | Affects cell proliferation, apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and metabolism | 58 | |

| Upregulated expression of miR-506 | Decreases the level of InsP3R3 | 59 |

Table 3.

Genetics of autoimmune diseases

| Diseases | Genes | Chro. | Influences | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLE | FCGRs | 1q23.3 | Contributes to the incomplete clearance of immune complexes | 60 |

| PTPN22 | 1p 13.3–13.1 | Increases the formation and deposition of immune complexes | 61 | |

| IL10 | 1q 31–32 | Suppresses expression of proinflammatory cytokines | 62, 63 | |

| C1Q | 4 D3 | Associated with neuropsychiatric SLE | 64 | |

| TNFα | 6p 21.33 | Regulates inflammation and apoptosis | 65 | |

| TNFβ | 6 | Represents a risk factor in Korean SLE and nephritis in patients with SLE | 66 | |

| PDCD1 | 2q 37.3 | Affects the binding affinity and activity of NFkB and RUNX1 | 64 | |

| CTLA4 | 2 q33 | Mediates antigen-specific apoptosis of T cells and suppresses autoreactive proliferation of T lymphocytes | 67, 68 | |

| RA | PTPN22 | 1p 13.3–13.1 | Enhances neutrophil effector functions | 69 |

| IL23R | 1p31.3 | Over-expression in the synovial fibroblasts and plasma | 70 | |

| TRAF1 | 9q33.2 | Negatively regulates Toll-like receptor signaling | 71 | |

| CTLA4 | 2q33.2 | Contributes to susceptibility | 72 | |

| IRF5 | 7q32.1 | Mediates proinflammatory cytokine production | 73 | |

| STAT4 | 2q32 | Overexpression in peripheral blood leukocytes and synovial fluid cells | 74 | |

| CCR6 | 6q27 | Mutations in CCR6 result in either a gain or loss of receptor function | 75 | |

| PADI4 | 1p36.13 | Protects fibroblast-like synoviocytes from apoptosis | 76 | |

| T1D | CTLA4 | 2 q33 | Involved in immune tolerance | 77 |

| PTPN22 | 1p 13.3–13.1 | Modulates intracellular signaling | 78 | |

| IL2RA | 10p15.1 | Involved in Treg cell suppressive function | 48 | |

| CLEC16A | 16p13.13 | Protective factor of T1D | 48 | |

| STAT4 | 2q32 | Influences cytokine signaling | 49 | |

| PBC | IL12A | 3q25.33 | Contributes to susceptibility | 79 |

| IL12RB2 | 1p31.3 | Contributes to susceptibility | 79 | |

| STAT4 | 2q32 | Contributes to susceptibility and ANA status in the Japanese population | 54 | |

| DENND1B | 1q31 | Contributes to susceptibility | 80 | |

| CD80 | 3q13 | Contributes to susceptibility | 81 | |

| IL7R | 5p13 | Contributes to susceptibility | 81 | |

| CXCR5 | 11q23 | Contributes to susceptibility | 82 | |

| TNFRSF1A | 12p13 | Contributes to susceptibility | 82 | |

| CLEC16A | 16q24 | Contributes to T cell hyporeactivity | 83 | |

| NFKB1 | 4q24 | Contributes to susceptibility | 82 |

Genetic and epigenetic influences on SLE

SLE is a systemic, multiple-organ involved autoimmune disease with a spectrum of clinical manifestations and outcomes, characterized by the production of pathogenic autoantibodies targeting nucleic acids and their binding proteins. It is a typical model of a global loss of tolerance with the activation of autoreactive T and B cells.31

Genetic factors of SLE

Genetic contributions to human lupus are well-established based on the fact that there is a significant difference in disease concordance between monozygotic twins (25–57%) and dizygotic twins (2–9%).32 Chromosome 1 consists of some of the loci most consistently recognized in SLE. The linkage interval 1q23 encodes Fcγ receptors FCGR2A and FCGR3A. The variants of different affinities for IgG and its subclasses of FCGRs contribute to incomplete clearance of immune complexes, leading to deposition in the kidney and blood vessels.33 Other disease-associated genes on chromosome 1 are PTPN22,34IL10(refs35,36) and C1Q.37

Genes encoding the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and components of the complement pathway (C2, C4) and TNFα and TNFβ reside in chromosome 6, and their polymorphisms have been demonstrated to be susceptible to SLE.38,40 Programmed cell death 1 gene (PDCD1) is upregulated in T cells, inhibiting TCR signaling and T/B cell survival. It is implicated that one intronic SNP in PDCD1 is associated with the development of SLE in Europeans. The SNP alteration on the associated allele affects the binding site for the runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1), suggesting a contribution to the development of SLE in humans.41 CTLA4, a negative costimulatory molecule, inhibits T cell activation and may limit T cell responses under inflammation. Genetic variability in CTLA4 has also been linked to SLE development.41,42

Epigenetic factors of SLE

Global DNA hypomethylation in T cells is a characterized epigenetic feature in SLE, resulting in the activation of transcription and close correlations with disease activity.43 Numerous studies have validated the critical roles of T cell DNA hypomethylation in the pathogenesis of SLE.44,45 Hypomethylation at specific regulatory regions of DNA is the reason for the overexpression of autoimmune-associated genes in lupus CD4+ T cells, contributing to the pathogenesis and development of SLE. CD11a, CD40L and CD70 are well-known examples.46,47,48 Lupus-associated inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-6, are epigenetically regulated by DNA demethylation.49 During T cell activation and differentiation, DNA methylation of specific genes plays vital roles in the process. For example, Foxp3, a gene for maintaining Treg cell function, is also closely controlled by DNA methylation.50 Additionally, transcription factors may participate in the regulation of DNA methylation. The down-regulation of RFX1 found in transcript factors screening in SLE CD4+ T cells inhibits the recruitment of DNMT1 and histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) to the promoter regions of CD70 and CD11a, leading to DNA hypomethylation and histone H3 hyperacetylation at these promoters.51 Growth arrest and DNA damage-induced 45alpha (Gadd45a) functions reduce the epigenetic silencing of genes via removing methylation marks. Upregulated Gadd45a in CD4+ T cells from SLE patients promotes DNA demethylation and stimulates the expression of methylation-sensitive genes including CD70 and CD11a.52 High mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1) may also be involved in DNA demethylation by binding to Gadd45a.53

Histone modification is another important epigenetic mechanism for regulating gene expression. Global hypoacetylation of histone H3 and H4 has been discovered in lupus CD4+ T cells.54 CD70 overexpression on T cells occurs partly because of aberrant histone modifications within the TNFSF7 promoter.55 Transcription factor cAMP-responsive element modulator (CREMα) mediates silencing of the IL2 gene in SLE T cells though the deacetylation of histone H3K18 and DNA hypermethylation.56 In addition to T cells, significant alterations of H3K4me3 in various key candidate genes was observed in lupus PBMCs,57 and altered global H4 acetylation was found in lupus monocytes.57

miRNAs are a large group of small, non-coding RNAs that function as post-transcriptional and posttranslational regulators of gene expression by binding to the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of the mRNA of a target gene. Based on the different cell types and tissues in lupus, aberrant expression of miRNA can be observed in T cells, B cells, dendritic cells and serum. For example, increased miR-21, miR-126 and miR148a were found in SLE T cells and DNMT1 is their target, contributing to DNA hypomethylation in SLE CD4+ T cells.58,59 miR-142 and miR-31 are believed to regulate T cells by inhibiting IL-4, IL-10, CD40L and ICOS expression and stimulating IL-2 production, respectively.60 A recent study on the pharmacological mechanisms of mycophenolic acid (MPA) on CD4+ T cells in SLE patients shows that miR-142 and miR-146a expression was increased after MPA activation through histone modification at the promoter region.61 In SLE B cells, the over-expression of miR-30a is responsible for the reduction of Lyn, suggesting that miR-30a plays an important role in B cell hyperactivity.62

Genetic and epigenetic influences on RA

RA is a chronic and systemic autoimmune disease characterized by chronic inflammation and the destruction of peripheral joints. As discovered in other autoimmune diseases, such as SLE, the development of RA also requires the combination of genetic susceptibility factors and environmental influences.63,64

Genetic factors in RA

Genetic factors contribute to the development of at least 50% of RA patients based on the data of familial and twin studies, and the concordance rate in monozygotic twins is 12–30%. The prevalence of RA is also high in first-degree relatives.65 HLA genes at 6p21 and HLA-DRB1 allele variants are closely associated to RA.66 In addition to the HLA loci, many other genes related to RA have been recognized. Thanks to the development of GWAS and single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array genotyping, numerous candidate genes have been identified,67 but few have been studied for their biological function. The most relevant non-HLA genes associated with RA include PTPN22,68IL23R,69TRAF1,70CTLA4,71IRF5,72STAT4,73CCR6(ref.74) and PADI4.71,75

Epigenetic factors in RA

DNA methylation status in blood cells, synovium and synovial fibroblasts in RA has been investigated. Although a global hypomethylation in T cells from RA patients has been observed, there is no proof of the association between methylation levels and disease activity.76 However, changes in DNA methylation in RA synovium and synovial fibroblasts have been reported. A genome-wide evaluation of DNA methylation loci in fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) isolated from the area of the disease in RA was performed. Compared to osteoarthritis (OA), 1 859 differentially methylated loci, mostly associated with immune cell trafficking, cell adhesion, and extracellular matrix interactions, were revealed in the FLS of RA.77 A global DNA hypomethylation in RA synovial fibroblasts has also been demonstrated.78 Furthermore, methylation changes of a single gene also participate in the pathogenesis of RA. For example, demethylation of the IL-6 promoter in PBMCs from patients with RA results in the over-expression of IL-6,79 which occurs in the serum, synovial tissue, and synovial fluid from patients with RA.80 Hypomethylation of CXCL12 in RA synovial fibroblasts promotes matrix metalloproteinases and joint destruction.81

The complexity of histone modifications gives rise to difficulties in investigating their exact mechanisms in RA, and studies were limited in the extent of the expression of histone-modifying enzymes. Conflicting data on the expression of HDACs in PBMCs and synovial tissues in RA patients were published, partly because of the diverse HDAC activities influenced by disease activity and therapy in patients enrolled in these studies.82,83,84,85 In synovial fibroblasts, increased expression of H3K4me3 in the promoters of MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-9 and MMP-13 and decreased expression of H3K27me3 in the promoters of MMP-1 and MMP-9 were obsevered.86 Moreover, increased histone acetylation leads to up-regulations of MMP-1 and IL-6 in synovial fibroblasts.87,88 These epigenetic changes provide a reasonable explanation for the over-expression of MMPs and IL-6 in RA synovial fibroblasts.

In 2008, compared to OA patients, the first screening of differentially expressed miRNAs identified overexpressed miRNA-155 and 146a in synovial fibroblasts from RA patients.89 A recent study revealed that the target of miRNA-155 is PU.1, a transcription factor in early B cell commitment, which is downregulated during B-cell maturation. The repression of endogenous miRNA-155 levels in B cells of RA patients results in the upregulation of PU.1 and the downregulation of the antibody production.90 Components of the toll-like receptor pathway, IRAK1 and TRAF6, are targets of miRNA-146a, but there is no difference in their levels in PBMCs from RA patients and healthy controls,91 indicating that increased miRNA-146a alone is insufficient to restrain inflammation. Compared to OA synovial fibroblasts, miRNA-124a, which targets monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1) and cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), was decreased in RA, leading to decreased proliferation of synovial fibroblasts.92 The only deregulated miRNA in the peripheral T lymphocytes of RA patients was miRNA-223, which is positively correlated with rheumatoid factor (RF) titers.93 Furthermore, increased miRNA-223 levels suppressed the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R)-mediated IL-10 production in T cells from RA patients.94

Genetic and epigenetic influences on T1D

T1D is an autoimmune disease resulting from T cell-mediated β cell destruction in genetically susceptible individuals with involvement of both genetic and environ-mental factors.95

Genetic factors in T1D

T1D is one of the most common heritable diseases, although a positive family history of T1D is confirmed in only 10 to 15% of newly diagnosed patients. To date, more than 50 susceptibility regions have been recognized to be linked with T1D. In T1D, the HLA class II alleles (primarily the HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1 loci) are the main susceptibility genes, and up to 50% of them have genetic risks.96 HLA-DRB1 and DQB1 are consistently associated with T1D in almost all ethnic groups.97 In addition to HLA class II, HLA class I genes have also been considered to be strongly associated with T1D. Among HLA class I genes, the HLA-B*39 allele, which significantly increases the risk of T1D, has one of the strongest associations with T1D.95 Moreover, multiple non-HLA loci also contribute to disease risks, such as CTLA4,98PTPN22,99IL2RA,100CLEC16A,100PTPN2(ref.99) and STAT4.101,102,103

Epigenetic factors in T1D

Compared to healthy controls, the global DNA methylation level is significantly increased in CD4+ T cells in patients with latent autoimmune diabetes of adults (LADA), accompanied by the upregulated expression level of DNMT3b.104 The DNA methylation level of nineteen CpG sites correlated with the time of onset of nephropathy were identified in a genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of T1D patients with diabetic nephropathy, and one of the CpG sites located nearby gene UNC13B has been indicated to reflect a risk of diabetic nephropathy in T1D.105

Studies have revealed that HDAC expression was aberrant in T1D patients. Decreases in H3K9Ac at the upstream promoter regions of HLA-DRB1 and an increase in H3K9Ac at the upstream promoter/enhancer region of HLA-DQB1 were noted in patients with T1D and healthy controls, and both genes are highly associated with T1D.106 Upregulated acetylated histone H4 levels were associated with T1D patients without vascular complications, suggesting a protective role against vascular injury in T1D.107 Genome-wide histone H3K9me2 patterns in peripheral lymphocytes and monocytes from T1D patients and normal controls were compared, presenting a significant increase in methylation levels of H3K9me2 in several high-risk genes for T1D, including the CTLA4 gene.108

Accumulating data support a role for miRNA in the development of T1D. miR-326 was found to be significantly increased in PBMCs from patients with T1D and positively correlated with disease severity, playing important stimulatory effects toward the development of T1D by targeting important immune regulators.109 Downregulated miR-21a and miR-93 were noticed in the PBMCs of T1D patients in the presence of incubation with glucose; however, no association with autoimmunity was observed.110 Global miRNA profiles in PBMCs from newly diagnosed T1D patients revealed that the most downregulated miRNA, miR-146, was associated with the ongoing autoimmune imbalance in T1D.111

Genetic and epigenetic influences on PBC

PBC, which is associated with both genetic and environmental factors, is a chronic, cholestatic autoimmune liver disease and may progress to liver cirrhosis and eventually liver failure.112,113

Genetic factors in PBC

Growing evidence indicates that PBC is a genetic-related condition, which was supported by familial clustering, the monozygotic twin concordance and the high prevalence of other autoimmune disorders in PBC patients and their family members.114 Similar to many other AIDs, the major genetic elements of PBC are found within the HLA region. The HLA class II DRB1*08 allele family shows the strongest association between specific HLA alleles and PBC susceptibility.115 Other loci, such as HLA DRB1, DQB1, DPB1, DRA, and c6orf10, are also strongly related to PBC susceptibility, as implicated in a GWAS study.116 Interestingly, specific class II HLA alleles function to protect against PBC, such as DQA1*0102, DQB1*0602, DRB1*13 and DRB1*11.115,117,118,119 Moreover, many non-HLA risk loci associated with PBC susceptibility have been discovered in high-throughput genetic studies, such as interleukin 12A (IL12A),116IL12RB2 loci,116STAT4,120DENND1B,121CD80,122IL7R,122CXCR5,123TNFRSF1A,123CLEC16A124 and NFKB1.116,123

Epigenetic factors of PBC

Recently, DNA methylation profiles in 60 differentially methylated regions corresponding to 51 genes on the X chromosome and nine genes on autosomal chromosomes were identified in twins of PBC patients and normal twins. DNA hypermethylation was observed in specific gene families such as ATP12A, ATP5A1 and HOXD4, suggesting DNA methylation as a regulator in the pathogenesis of PBC.125 A significant DNA demethylation level at the CD40L promoter is inversely correlated with IgM serum levels in CD4+ T cells from PBC patients,126 supporting the involvement of methylation modifications of CD40L in the development of PBC. Thus far, histone modification dysregulation in PBC remains under investigation.

Dysregulated histone modifications of genes demonstrated in autoreactive T cells with PBC patients include upregulated histone H4 acetylation in the promoter regions CD40L, LIGHT, IL17 and IFNG and downregulated histone H4 acetylation in the promoter regions of TRAIL, Apo2 and HDAC7A.127

A total of 35 independent miRNAs were found to be differentially expressed in the tissues from PBC patients, with predicted targets belonging to cell proliferation, apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and metabolism. The downregulation of microRNA-122a (miR-122a) and miR-26a and the increased expression of miR-328 and miR-299-5p were validated.128 One example is miR26-a, contributing as a post-transcriptional regulator of the overexpression of a polycomb group protein EZH2 in PBC.129,130 One miRNA for a PBC target cell (cholangiocytes) is miR-506,131 which is capable of regulating pH homeostasis by decreasing the level of InsP3R3, an intracellular Ca channel.132

Conclusion

Great progress in understanding the development and pathogenesis of AIDs has been made in recent decades, particularly with the advent of epigenetic research, which has created a bridge between genetic and environmental factors. It is believed that both genetic and epigenetic factors influence the process and development of immune tolerance on different levels. However, an exact and full picture of the network related to gene expression and epigenetic modifications on the mechanisms of loss of tolerance is urged to provide new perspectives on autoimmunity.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No.14JJ1009) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81522038 and No. 81220108017).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised: in the caption of figure 1(a), the sentence: “In the thymus, both high-affinity T and B cells undergo apoptosis” was corrected as follows: “In the thymus, T cells with high affinity for self-antigens undergo apoptosis, while B cells undergo a similar process in the bone marrow.”

Change history

7/29/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41423-024-01201-6

References

- 1.Carvalheiras G, Faria R, Braga J, Vasconcelos C. Fetal outcome in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev 2012; 11: A520–530. 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alarcon-Riquelme ME. Recent advances in the genetics of autoimmune diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007; 1110: 1–9. 10.1196/annals.1423.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strickland FM, Richardson BC. Epigenetics in human autoimmunity. Epigenetics in autoimmunity - DNA methylation in systemic lupus erythematosus and beyond. Autoimmunity 2008; 41: 278–286. 10.1080/08916930802024616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jerne NK. The somatic generation of immune recognition. 1971. Eur J Immunol 2004; 34: 1234–1242. 10.1002/eji.200425132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker LS, Abbas AK. The enemy within: keeping self-reactive T cells at bay in the periphery. Nat Rev Immunol 2002; 2: 11–19. 10.1038/nri701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng MH, Anderson MS. Monogenic autoimmunity. Annu Rev Immunol 2012; 30: 393–427. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finnish-German AC. An autoimmune disease, APECED, caused by mutations in a novel gene featuring two PHD-type zinc-finger domains. Nat Genet 1997; 17: 399–403. 10.1038/ng1297-399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagamine K, Peterson P, Scott HS, Kudoh J, Minoshima S, Heino M et al. Positional cloning of the APECED gene. Nat Genet 1997; 17: 393–398. 10.1038/ng1297-393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liston A, Lesage S, Wilson J, Peltonen L, Goodnow CC. Aire regulates negative selection of organ-specific T cells. Nat Immunol 2003; 4: 350–354. 10.1038/ni906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Pillars Article: Control of Regulatory T Cell Development by the Transcription Factor Foxp3. Science 2003; 299: 1057–1061J Immunol 2017; 198: 981–985. 10.1126/science.1079490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol 2003; 4: 330–336. 10.1038/ni904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khattri R, Cox T, Yasayko SA, Ramsdell F. An essential role for Scurfin in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Nat Immunol 2003; 4: 337–342. 10.1038/ni909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramsdell F, Ziegler SF. FOXP3 and scurfy: how it all began. Nat Rev Immunol 2014; 14: 343–349. 10.1038/nri3650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salomon B, Bluestone JA. Complexities of CD28/B7: CTLA-4 costimulatory pathways in autoimmunity and transplantation. Annu Rev Immunol 2001; 19: 225–252. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klocke K, Sakaguchi S, Holmdahl R, Wing K. Induction of autoimmune disease by deletion of CTLA-4 in mice in adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016; 113: E2383–2392. 10.1073/pnas.1603892113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ueda H, Howson JM, Esposito L, Heward J, Snook H, Chamberlain G et al. Association of the T-cell regulatory gene CTLA4 with susceptibility to autoimmune disease. Nature 2003; 423: 506–511. 10.1038/nature01621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenardo M, Chan KM, Hornung F, McFarland H, Siegel R, Wang J et al. Mature T lymphocyte apoptosis—immune regulation in a dynamic and unpredictable antigenic environment. Annu Rev Immunol 1999; 17: 221–253. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer A, Rieux-Laucat F, Le Deist F. Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndromes (ALPS): models for the study of peripheral tolerance. Rev Immunogenet 2000; 2: 52–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Northrop JK, Thomas RM, Wells AD, Shen H. Epigenetic remodeling of the IL-2 and IFN-gamma loci in memory CD8 T cells is influenced by CD4 T cells. J Immunol 2006; 177: 1062–1069. 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruniquel D, Schwartz RH. Selective, stable demethylation of the interleukin-2 gene enhances transcription by an active process. Nat Immunol 2003; 4: 235–240. 10.1038/ni887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makar KW, Wilson CB. DNA methylation is a nonredundant repressor of the Th2 effector program. J Immunol 2004; 173: 4402–4406. 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medvedovic J, Ebert A, Tagoh H, Busslinger M. Pax5: a master regulator of B cell development and leukemogenesis. Adv Immunol 2011; 111: 179–206. 10.1016/B978-0-12-385991-4.00005-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bandyopadhyay S, Dure M, Paroder M, Soto-Nieves N, Puga I, Macian F. Interleukin 2 gene transcription is regulated by Ikaros-induced changes in histone acetylation in anergic T cells. Blood 2007; 109: 2878–2886. 10.1182/blood-2006-07-037754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fields PE, Kim ST, Flavell RA. Cutting edge: changes in histone acetylation at the IL-4 and IFN-gamma loci accompany Th1/Th2 differentiation. J Immunol 2002; 169: 647–650. 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avni O, Lee D, Macian F, Szabo SJ, Glimcher LH, Rao A. T(H) cell differentiation is accompanied by dynamic changes in histone acetylation of cytokine genes. Nat Immunol 2002; 3: 643–651. 10.1038/ni808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei G, Wei L, Zhu J, Zang C, Hu-Li J, Yao Z et al. Global mapping of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 reveals specificity and plasticity in lineage fate determination of differentiating CD4+ T cells. Immunity 2009; 30: 155–167. 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin YC, Jhunjhunwala S, Benner C, Heinz S, Welinder E, Mansson R et al. A global network of transcription factors, involving E2A, EBF1 and Foxo1, that orchestrates B cell fate. Nat Immunol 2010; 11: 635–643. 10.1038/ni.1891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuchen S, Resch W, Yamane A, Kuo N, Li Z, Chakraborty T et al. Regulation of microRNA expression and abundance during lymphopoiesis. Immunity 2010; 32: 828–839. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singleton AB, Hardy J, Traynor BJ, Houlden H. Towards a complete resolution of the genetic architecture of disease. Trends Genet 2010; 26: 438–442. 10.1016/j.tig.2010.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Long H, Yin H, Wang L, Gershwin ME, Lu Q. The critical role of epigenetics in systemic lupus erythematosus and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun 2016; 74: 118–138. 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shlomchik MJ, Craft JE, Mamula MJ. From T to B and back again: positive feedback in systemic autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2001; 1: 147–153. 10.1038/35100573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jarvinen P, Aho K. Twin studies in rheumatic diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1994; 24: 19–28. 10.1016/0049-0172(94)90096-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karassa FB, Trikalinos TA, Ioannidis JP. The role of FcgammaRIIA and IIIA polymorphisms in autoimmune diseases. Biomed Pharmacother 2004; 58: 286–291. 10.1016/j.biopha.2004.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kyogoku C, Langefeld CD, Ortmann WA, Lee A, Selby S, Carlton VE et al. Genetic association of the R620W polymorphism of protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPN22 with human SLE. Am J Hum Genet 2004; 75: 504–507. 10.1086/423790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suarez A, Lopez P, Mozo L, Gutierrez C. Differential effect of IL10 and TNF{alpha} genotypes on determining susceptibility to discoid and systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64: 1605–1610. 10.1136/ard.2004.035048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosado S, Rua-Figueroa I, Vargas JA, Garcia-Laorden MI, Losada-Fernandez I, Martin-Donaire T et al. Interleukin-10 promoter polymorphisms in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus from the Canary Islands. Int J Immunogenet 2008; 35: 235–242. 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2008.00762.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sestak AL, Nath SK, Sawalha AH, Harley JB. Current status of lupus genetics. Arthritis Res Ther 2007; 9: 210. 10.1186/ar2176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tarassi K, Carthy D, Papasteriades C, Boki K, Nikolopoulou N, Carcassi C et al. HLA-TNF haplotype heterogeneity in Greek SLE patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1998; 16: 66–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sullivan KE, Suriano A, Dietzmann K, Lin J, Goldman D, Petri MA. The TNFalpha locus is altered in monocytes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Immunol 2007; 123: 74–81. 10.1016/j.clim.2006.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim HY, Lee SH, Yang HI, Park SH, Cho CS, Kim TG et al. TNFB gene polymorphism in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in Korean. Korean J Intern Med 1995; 10: 130–136. 10.3904/kjim.1995.10.2.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prokunina L, Castillejo-Lopez C, Oberg F, Gunnarsson I, Berg L, Magnusson V et al. A regulatory polymorphism in PDCD1 is associated with susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus in humans. Nat Genet 2002; 32: 666–669. 10.1038/ng1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parks CG, Hudson LL, Cooper GS, Dooley MA, Treadwell EL St, Clair EW et al. CTLA-4 gene polymorphisms and systemic lupus erythematosus in a population-based study of whites and African-Americans in the southeastern United States. Lupus 2004; 13: 784–791. 10.1191/0961203304lu1085oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Zhao M, Sawalha AH, Richardson B, Lu Q. Impaired DNA methylation and its mechanisms in CD4(+)T cells of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun 2013; 41: 92–99. 10.1016/j.jaut.2013.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yung RL, Richardson BC. Role of T cell DNA methylation in lupus syndromes. Lupus 1994; 3: 487–491. 10.1177/096120339400300611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou Y, Lu Q. DNA methylation in T cells from idiopathic lupus and drug-induced lupus patients. Autoimmun Rev 2008; 7: 376–383. 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu Q, Kaplan M, Ray D, Ray D, Zacharek S, Gutsch D et al. Demethylation of ITGAL (CD11a) regulatory sequences in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46: 1282–1291. 10.1002/art.10234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaplan MJ, Deng C, Yang J, Richardson BC. DNA methylation in the regulation of T cell LFA-1 expression. Immunol Invest 2000; 29: 411–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu Q, Wu A, Richardson BC. Demethylation of the same promoter sequence increases CD70 expression in lupus T cells and T cells treated with lupus-inducing drugs. J Immunol 2005; 174: 6212–6219. 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mi XB, Zeng FQ. Hypomethylation of interleukin-4 and -6 promoters in T cells from systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2008; 29: 105–112. 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00739.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lal G, Zhang N, van der Touw W, Ding Y, Ju W, Bottinger EP et al. Epigenetic regulation of Foxp3 expression in regulatory T cells by DNA methylation. J Immunol 2009; 182: 259–273. 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao M, Sun Y, Gao F, Wu X, Tang J, Yin H et al. Epigenetics and SLE: RFX1 downregulation causes CD11a and CD70 overexpression by altering epigenetic modifications in lupus CD4+ T cells. J Autoimmun 2010; 35: 58–69. 10.1016/j.jaut.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li Y, Zhao M, Yin H, Gao F, Wu X, Luo Y et al. Overexpression of the growth arrest and DNA damage-induced 45alpha gene contributes to autoimmunity by promoting DNA demethylation in lupus T cells. Arthritis Rheum 2010; 62: 1438–1447. 10.1002/art.27363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li Y, Huang C, Zhao M, Liang G, Xiao R, Yung S et al. A possible role of HMGB1 in DNA demethylation in CD4+ T cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Dev Immunol 2013; 2013: 206298. 10.1155/2013/206298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hu N, Qiu X, Luo Y, Yuan J, Li Y, Lei W et al. Abnormal histone modification patterns in lupus CD4+ T cells. J Rheumatol 2008; 35: 804–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou Y, Qiu X, Luo Y, Yuan J, Li Y, Zhong Q et al. Histone modifications and methyl-CpG-binding domain protein levels at the TNFSF7 (CD70) promoter in SLE CD4+ T cells. Lupus 2011; 20: 1365–1371. 10.1177/0961203311413412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hedrich CM, Rauen T, Tsokos GC. cAMP-responsive element modulator (CREM)alpha protein signaling mediates epigenetic remodeling of the human interleukin-2 gene: implications in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Biol Chem 2011; 286: 43429–43436. 10.1074/jbc.M111.299339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Z, Song L, Maurer K, Petri MA, Sullivan KE. Global H4 acetylation analysis by ChIP-chip in systemic lupus erythematosus monocytes. Genes Immun 2010; 11: 124–133. 10.1038/gene.2009.66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao S, Wang Y, Liang Y, Zhao M, Long H, Ding S et al. MicroRNA-126 regulates DNA methylation in CD4+ T cells and contributes to systemic lupus erythematosus by targeting DNA methyltransferase 1. Arthritis Rheum 2011; 63: 1376–1386. 10.1002/art.30196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pan W, Zhu S, Yuan M, Cui H, Wang L, Luo X et al. MicroRNA-21 and microRNA-148a contribute to DNA hypomethylation in lupus CD4+ T cells by directly and indirectly targeting DNA methyltransferase 1. J Immunol 2010; 184: 6773–6781. 10.4049/jimmunol.0904060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ding S, Liang Y, Zhao M, Liang G, Long H, Zhao S et al. Decreased microRNA-142-3p/5p expression causes CD4+ T cell activation and B cell hyperstimulation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64: 2953–2963. 10.1002/art.34505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tang Q, Yang Y, Zhao M, Liang G, Wu H, Liu Q et al. Mycophenolic acid upregulates miR-142-3P/5P and miR-146a in lupus CD4+T cells. Lupus 2015; 24: 935–942. 10.1177/0961203315570685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu Y, Dong J, Mu R, Gao Y, Tan X, Li Y et al. MicroRNA-30a promotes B cell hyperactivity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus by direct interaction with Lyn. Arthritis Rheum 2013; 65: 1603–1611. 10.1002/art.37912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tobon GJ, Youinou P, Saraux A. The environment, geo-epidemiology, and autoimmune disease: Rheumatoid arthritis. J Autoimmun 2010; 35: 10–14. 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fan W, Liang D, Tang Y, Qu B, Cui H, Luo X et al. Identification of microRNA-31 as a novel regulator contributing to impaired interleukin-2 production in T cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64: 3715–3725. 10.1002/art.34596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alarcon-Segovia D, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Cardiel MH, Caeiro F, Massardo L, Villa AR et al. Familial aggregation of systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and other autoimmune diseases in 1,177 lupus patients from the GLADEL cohort. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52: 1138–1147. 10.1002/art.20999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Orozco G, Rueda B, Martin J. Genetic basis of rheumatoid arthritis. Biomed Pharmacother 2006; 60: 656–662. 10.1016/j.biopha.2006.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chung IM, Ketharnathan S, Thiruvengadam M, Rajakumar G. Rheumatoid Arthritis: The Stride from Research to Clinical Practice. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17: pii:E900. 10.3390/ijms17060900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bayley R, Kite KA, McGettrick HM, Smith JP, Kitas GD, Buckley CD et al. The autoimmune-associated genetic variant PTPN22 R620W enhances neutrophil activation and function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and healthy individuals. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74: 1588–1595. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rong C, Hu W, Wu FR, Cao XJ, Chen FH. Interleukin-23 as a potential therapeutic target for rheumatoid arthritis. Mol Cell Biochem 2012; 361: 243–248. 10.1007/s11010-011-1109-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abdul-Sater AA, Edilova MI, Clouthier DL, Mbanwi A, Kremmer E, Watts TH. The signaling adaptor TRAF1 negatively regulates Toll-like receptor signaling and this underlies its role in rheumatic disease. Nat Immunol 2017; 18: 26–35. 10.1038/ni.3618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kurko J, Besenyei T, Laki J, Glant TT, Mikecz K, Szekanecz Z. Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis - a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2013; 45: 170–179. 10.1007/s12016-012-8346-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Duffau P, Menn-Josephy H, Cuda CM, Dominguez S, Aprahamian TR, Watkins AA et al. Promotion of Inflammatory Arthritis by Interferon Regulatory Factor 5 in a Mouse Model. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015; 67: 3146–3157. 10.1002/art.39321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Swierkot J, Nowak B, Czarny A, Zaczynska E, Sokolik R, Madej M et al. The Activity of JAK/STAT and NF-kappaB in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Adv Clin Exp Med 2016; 25: 709–717. 10.17219/acem/61034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Julian B, Gao K, Harwood BN, Beinborn M, Kopin AS. Mutation-Induced Functional Alterations of CCR6. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2017; 360: 106–116. 10.1124/jpet.116.237669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fan L, Zong M, Gong R, He D, Li N, Sun LS et al. PADI4 Epigenetically Suppresses p21 Transcription and Inhibits Cell Apoptosis in Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes from Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Int J Biol Sci 2017; 13: 358–366. 10.7150/ijbs.16879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Richardson B, Scheinbart L, Strahler J, Gross L, Hanash S, Johnson M. Evidence for impaired T cell DNA methylation in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1990; 33: 1665–1673. 10.1002/art.1780331109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nakano K, Whitaker JW, Boyle DL, Wang W, Firestein GS. DNA methylome signature in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72: 110–117. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Karouzakis E, Gay RE, Michel BA, Gay S, Neidhart M. DNA hypomethylation in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60: 3613–3622. 10.1002/art.25018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nile CJ, Read RC, Akil M, Duff GW, Wilson AG. Methylation status of a single CpG site in the IL6 promoter is related to IL6 messenger RNA levels and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58: 2686–2693. 10.1002/art.23758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wood NC, Symons JA, Dickens E, Duff GW. In situ hybridization of IL-6 in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol 1992; 87: 183–189. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb02972.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Karouzakis E, Rengel Y, Jungel A, Kolling C, Gay RE, Michel BA et al. DNA methylation regulates the expression of CXCL12 in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Genes Immun 2011; 12: 643–652. 10.1038/gene.2011.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gillespie J, Savic S, Wong C, Hempshall A, Inman M, Emery P et al. Histone deacetylases are dysregulated in rheumatoid arthritis and a novel histone deacetylase 3-selective inhibitor reduces interleukin-6 production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64: 418–422. 10.1002/art.33382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Toussirot E, Abbas W, Khan KA, Tissot M, Jeudy A, Baud L et al. Imbalance between HAT and HDAC activities in the PBMCs of patients with ankylosing spondylitis or rheumatoid arthritis and influence of HDAC inhibitors on TNF alpha production. PLoS One 2013; 8: e70939. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Huber LC, Brock M, Hemmatazad H, Giger OT, Moritz F, Trenkmann M et al. Histone deacetylase/acetylase activity in total synovial tissue derived from rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum 2007; 56: 1087–1093. 10.1002/art.22512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kawabata T, Nishida K, Takasugi K, Ogawa H, Sada K, Kadota Y et al. Increased activity and expression of histone deacetylase 1 in relation to tumor necrosis factor-alpha in synovial tissue of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2010; 12: R133. 10.1186/ar3071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Araki Y, Tsuzuki Wada T, Aizaki Y, Sato K, Yokota K, Fujimoto K et al. Histone Methylation and STAT-3 Differentially Regulate Interleukin-6-Induced Matrix Metalloproteinase Gene Activation in Rheumatoid Arthritis Synovial Fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016; 68: 1111–1123. 10.1002/art.39563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Maciejewska-Rodrigues H, Karouzakis E, Strietholt S, Hemmatazad H, Neidhart M, Ospelt C et al. Epigenetics and rheumatoid arthritis: the role of SENP1 in the regulation of MMP-1 expression. J Autoimmun 2010; 35: 15–22. 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wada TT, Araki Y, Sato K, Aizaki Y, Yokota K, Kim YT et al. Aberrant histone acetylation contributes to elevated interleukin-6 production in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014; 444: 682–686. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.01.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stanczyk J, Pedrioli DM, Brentano F, Sanchez-Pernaute O, Kolling C, Gay RE et al. Altered expression of MicroRNA in synovial fibroblasts and synovial tissue in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58: 1001–1009. 10.1002/art.23386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Alivernini S, Kurowska-Stolarska M, Tolusso B, Benvenuto R, Elmesmari A, Canestri S et al. MicroRNA-155 influences B-cell function through PU.1 in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Commun 2016; 7: 12970. 10.1038/ncomms12970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pauley KM, Satoh M, Chan AL, Bubb MR, Reeves WH, Chan EK. Upregulated miR-146a expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Res Ther 2008; 10: R101. 10.1186/ar2493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nakamachi Y, Kawano S, Takenokuchi M, Nishimura K, Sakai Y, Chin T et al. MicroRNA-124a is a key regulator of proliferation and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 secretion in fibroblast-like synoviocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60: 1294–1304. 10.1002/art.24475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fulci V, Scappucci G, Sebastiani GD, Giannitti C, Franceschini D, Meloni F et al. miR-223 is overexpressed in T-lymphocytes of patients affected by rheumatoid arthritis. Hum Immunol 2010; 71: 206–211. 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lu MC, Yu CL, Chen HC, Yu HC, Huang HB, Lai NS. Increased miR-223 expression in T cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis leads to decreased insulin-like growth factor-1-mediated interleukin-10 production. Clin Exp Immunol 2014; 177: 641–651. 10.1111/cei.12374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Stankov K, Benc D, Draskovic D. Genetic and epigenetic factors in etiology of diabetes mellitus type 1. Pediatrics 2013; 132: 1112–1122. 10.1542/peds.2013-1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Noble JA, Erlich HA. Genetics of type 1 diabetes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012; 2: a007732. 10.1101/cshperspect.a007732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Thomson G, Valdes AM, Noble JA, Kockum I, Grote MN, Najman J et al. Relative predispositional effects of HLA class II DRB1-DQB1 haplotypes and genotypes on type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Tissue Antigens 2007; 70: 110–127. 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2007.00867.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Balic I, Angel B, Codner E, Carrasco E, Perez-Bravo F. Association of CTLA-4 polymorphisms and clinical-immunologic characteristics at onset of type 1 diabetes mellitus in children. Hum Immunol 2009; 70: 116–120. 10.1016/j.humimm.2008.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sharp RC, Abdulrahim M, Naser ES, Naser SA. Genetic Variations of PTPN2 and PTPN22: Role in the Pathogenesis of Type 1 Diabetes and Crohn's Disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2015; 5: 95. 10.3389/fcimb.2015.00095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Marwaha AK, Panagiotopoulos C, Biggs CM, Staiger S, Del Bel KL, Hirschfeld AF et al. Pre-diagnostic genotyping identifies T1D subjects with impaired Treg IL-2 signaling and an elevated proportion of FOXP3+IL-17+ cells. Genes Immun 2017; 18: 15–21. 10.1038/gene.2016.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nepom GT, Buckner JH. A functional framework for interpretation of genetic associations in T1D. Curr Opin Immunol 2012; 24: 516–521. 10.1016/j.coi.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Morahan G. Insights into type 1 diabetes provided by genetic analyses. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2012; 19: 263–270. 10.1097/MED.0b013e328355b7fe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Park Y, Lee HS, Park Y, Min D, Yang S, Kim D et al. Evidence for the role of STAT4 as a general autoimmunity locus in the Korean population. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2011; 27: 867–871. 10.1002/dmrr.1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Li Y, Zhao M, Hou C, Liang G, Yang L, Tan Y et al. Abnormal DNA methylation in CD4+ T cells from people with latent autoimmune diabetes in adults. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011; 94: 242–248. 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bell CG, Teschendorff AE, Rakyan VK, Maxwell AP, Beck S, Savage DA, Genome-wide DNA. methylation analysis for diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes mellitus. BMC Med Genomics 2010; 3: 33. 10.1186/1755-8794-3-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Miao F, Chen Z, Zhang L, Liu Z, Wu X, Yuan YC et al. Profiles of epigenetic histone post-translational modifications at type 1 diabetes susceptible genes. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 16335–16345. 10.1074/jbc.M111.330373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chen SS, Jenkins AJ, Majewski H. Elevated plasma prostaglandins and acetylated histone in monocytes in Type 1 diabetes patients. Diabet Med 2009; 26: 182–186. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02658.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Miao F, Smith DD, Zhang L, Min A, Feng W, Natarajan R. Lymphocytes from patients with type 1 diabetes display a distinct profile of chromatin histone H3 lysine 9 dimethylation: an epigenetic study in diabetes. Diabetes 2008; 57: 3189–3198. 10.2337/db08-0645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sebastiani G, Grieco FA, Spagnuolo I, Galleri L, Cataldo D, Dotta F. Increased expression of microRNA miR-326 in type 1 diabetic patients with ongoing islet autoimmunity. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2011; 27: 862–866. 10.1002/dmrr.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Salas-Perez F, Codner E, Valencia E, Pizarro C, Carrasco E, Perez-Bravo F. MicroRNAs miR-21a and miR-93 are down regulated in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients with type 1 diabetes. Immunobiology 2013; 218: 733–737. 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.08.276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yang M, Ye L, Wang B, Gao J, Liu R, Hong J et al. Decreased miR-146 expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells is correlated with ongoing islet autoimmunity in type 1 diabetes patients 1miR-146. J Diabetes 2015; 7: 158–165. 10.1111/1753-0407.12163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hirschfield GM, Gershwin ME. The immunobiology and pathophysiology of primary biliary cirrhosis. Annu Rev Pathol 2013; 8: 303–330. 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-164014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Poupon R. Primary biliary cirrhosis: a 2010 update. J Hepatol 201052: 745–758. 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Selmi C, Mayo MJ, Bach N, Ishibashi H, Invernizzi P, Gish RG et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis in monozygotic and dizygotic twins: genetics, epigenetics, and environment. Gastroenterology 2004; 127: 485–492. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Begovich AB, Klitz W, Moonsamy PV. Van de Water J, Peltz G, Gershwin ME. Genes within the HLA class II region confer both predisposition and resistance to primary biliary cirrhosis. Tissue Antigens 1994; 43: 71–77. 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1994.tb02303.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hirschfield GM, Liu X, Xu C, Lu Y, Xie G, Lu Y et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis associated with HLA, IL12A, and IL12RB2 variants. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 2544–2555. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Donaldson PT, Baragiotta A, Heneghan MA, Floreani A, Venturi C, Underhill JA et al. HLA class II alleles, genotypes, haplotypes, and amino acids in primary biliary cirrhosis: a large-scale study. Hepatology 2006; 44: 667–674. 10.1002/hep.21316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Onishi S, Sakamaki T, Maeda T, Iwamura S, Tomita A, Saibara T et al. DNA typing of HLA class II genes; DRB1*0803 increases the susceptibility of Japanese to primary biliary cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1994; 21: 1053–1060. 10.1016/S0168-8278(05)80617-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Invernizzi P, Battezzati PM, Crosignani A, Perego F, Poli F, Morabito A et al. Peculiar HLA polymorphisms in Italian patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2003; 38: 401–406. 10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00440-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Joshita S, Umemura T, Nakamura M, Katsuyama Y, Shibata S, Kimura T et al. STAT4 gene polymorphisms are associated with susceptibility and ANA status in primary biliary cirrhosis. Dis Markers 2014; 2014: 727393. 10.1155/2014/727393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Nakamura M, Nishida N, Kawashima M, Aiba Y, Tanaka A, Yasunami M et al. Genome-wide association study identifies TNFSF15 and POU2AF1 as susceptibility loci for primary biliary cirrhosis in the Japanese population. Am J Hum Genet 2012; 91: 721–728. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Dong M, Li J, Tang R, Zhu P, Qiu F, Wang C et al. Multiple genetic variants associated with primary biliary cirrhosis in a Han Chinese population. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2015; 48: 316–321. 10.1007/s12016-015-8472-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mells GF, Floyd JA, Morley KI, Cordell HJ, Franklin CS, Shin SY et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 12 new susceptibility loci for primary biliary cirrhosis. Nat Genet 2011; 43: 329–332. 10.1038/ng.789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Schuster C, Gerold KD, Schober K, Probst L, Boerner K, Kim MJ et al. The Autoimmunity-Associated Gene CLEC16A Modulates Thymic Epithelial Cell Autophagy and Alters T Cell Selection. Immunity 2015; 42: 942–952. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Selmi C, Cavaciocchi F, Lleo A, Cheroni C, De Francesco R, Lombardi SA et al. Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation, copy number variation, and gene expression in monozygotic twins discordant for primary biliary cirrhosis. Front Immunol 2014; 5: 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lleo A, Liao J, Invernizzi P, Zhao M, Bernuzzi F, Ma L et al. Immunoglobulin M levels inversely correlate with CD40 ligand promoter methylation in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology 2012; 55: 153–160. 10.1002/hep.24630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Hu Z, Huang Y, Liu Y, Sun Y, Zhou Y, Gu M et al. beta-Arrestin 1 modulates functions of autoimmune T cells from primary biliary cirrhosis patients. J Clin Immunol 2011; 31: 346–355. 10.1007/s10875-010-9492-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Padgett KA, Lan RY, Leung PC, Lleo A, Dawson K, Pfeiff J et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis is associated with altered hepatic microRNA expression. J Autoimmun 2009; 32: 246–253. 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sasaki M, Ikeda H, Sato Y, Nakanuma Y. Decreased expression of Bmi1 is closely associated with cellular senescence in small bile ducts in primary biliary cirrhosis. Am J Pathol 2006; 169: 831–845. 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sander S, Bullinger L, Klapproth K, Fiedler K, Kestler HA, Barth TF et al. MYC stimulates EZH2 expression by repression of its negative regulator miR-26a. Blood 2008; 112: 4202–4212. 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Banales JM, Saez E, Uriz M, Sarvide S, Urribarri AD, Splinter P et al. Up-regulation of microRNA 506 leads to decreased Cl-/HCO3- anion exchanger 2 expression in biliary epithelium of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology 2012; 56: 687–697. 10.1002/hep.25691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ananthanarayanan M, Banales JM, Guerra MT, Spirli C, Munoz-Garrido P, Mitchell-Richards K et al. Post-translational regulation of the type III inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor by miRNA-506. J Biol Chem 2015; 290: 184–196. 10.1074/jbc.M114.587030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]