Summary

Cotton cultivars have evolved to produce extensive, long, seed‐born fibers important for the textile industry, but we know little about the molecular mechanism underlying spinnable fiber formation. Here, we report how PACLOBUTRAZOL RESISTANCE 1 (PRE1) in cotton, which encodes a basic helix‐loop‐helix (bHLH) transcription factor, is a target gene of spinnable fiber evolution.

Differential expression of homoeologous genes in polyploids is thought to be important to plant adaptation and novel phenotypes. PRE1 expression is specific to cotton fiber cells, upregulated during their rapid elongation stage and A‐homoeologous biased in allotetraploid cultivars. Transgenic studies demonstrated that PRE1 is a positive regulator of fiber elongation.

We determined that the natural variation of the canonical TATA‐box, a regulatory element commonly found in many eukaryotic core promoters, is necessary for subgenome‐biased PRE1 expression, representing a mechanism underlying the selection of homoeologous genes.

Thus, variations in the promoter of the cell elongation regulator gene PRE1 have contributed to spinnable fiber formation in cotton. Overexpression of GhPRE1 in transgenic cotton yields longer fibers with improved quality parameters, indicating that this bHLH gene is useful for improving cotton fiber quality.

Keywords: allopolyploid, Gossypium hirsutum, Homoeolog, molecular evolution, PRE1, TATA‐box

Introduction

Polyploids, which harbor two or more sets of genomes in their nuclei, are common in flowering plants (Soltis et al., 2014). Many crops are neo‐allopolyploids, such as the upland cotton Gossypium hirsutum and the extra‐long staple (ELS) cotton G. barbadense, both of which are allotetraploids (Gong et al., 2013; Renny‐Byfield & Wendel, 2014; Wendel & Grover, 2015). Exploring the mechanisms that regulate the expression of homoeologous gene pairs may generate clues regarding the origin of important traits that have arisen during the evolution and domestication of polyploid crops (Fang et al., 2017b; Wang et al., 2017).

Cotton is the major source of natural fiber for the textile industry. Cotton fibers, which are single‐celled, epidermal seed trichomes, have two remarkable features: extreme length (may exceed 4 cm) and high (> 95%) cellulose content at maturity (Kim & Triplett, 2001; Mansoor & Paterson, 2012). After initiation from the outer integument before the day of anthesis, cotton fiber cells undergo rapid primary cell wall elongation until c. 2–3 wk after anthesis, before entering into secondary cell wall synthesis (Applequist et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2007; Mansoor & Paterson, 2012).

A series of transcriptional factors involved in regulation of cotton fiber development have been reported. Both transgenic and genetic mapping results indicate that the MIXTA‐type R2R3 MYB (myeloblastosis) transcription factor MYB25‐like and its homoeologs function as the master regulator of fiber cell initiation and early development (Walford et al., 2011; Tan et al., 2016; Wan et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2018). Additionally, the GL1‐type MYBs may also play a role, because all homoeologs of the Arabidopsis MYB‐bHLH‐WD40 (MBW) complex (Szymanski et al., 2000) are expressed in cotton fibers (Shangguan et al., 2008). During elongation, the phytohormone gibberellin (GA) plays a key role in promoting fiber growth, during which GhHOX3, an homoeodomain leucine zipper (HD‐ZIP) IV transcription factor, acts as a core regulator (Rombola‐Caldentey et al., 2014; Shan et al., 2014). Because cell elongation involves multiple signaling pathways and cotton fiber cells are unique in their extensive and synchronous elongation, isolation of new regulators will further our understanding of the molecular basis of cotton fiber development and of plant cell growth in general.

The cotton genus Gossypium (Malvaceae) includes > 50 species (Wendel & Grover, 2015). None of the c. 45 diploids (2n = 26), which are divided into eight (A to G and K) genome groups (Wendel & Grover, 2015), produce spinnable fiber except for the two A‐genome species G. herbaceum and G. arboreum. Allopolyploid species formed c. 1–2 Myr ago through hybridization between A and D genome species (Wendel et al., 2010; Wendel & Grover, 2015), and accordingly, they contain two subgenomes, designated At and Dt (with the t denoting subgenome in the tetraploid). Of the seven allotetraploid cotton species identified to date (Grover et al., 2014, 2015; Gallagher et al., 2017), G. hirsutum and G. barbadense have been domesticated and are now widely cultivated for fiber and other byproducts (Wendel et al., 2009, 2010; Renny‐Byfield et al., 2016).

Recent progress in genomic analyses of cottons (Paterson et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014, 2015; Liu et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015) have generated extensive data for cotton research and breeding. The tetraploid cottons have a relatively large genome of c. 2.5 Gb, > 60% comprising repetitive sequences (Li et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015). The two subgenomes, At and Dt, are largely collinear and syntenic, although they differ approximately two‐fold in genome size (Paterson et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014, 2015; Liu et al., 2015; Wendel & Grover, 2015; Zhang et al., 2015). Polyploidization in plants is known to induce a wide spectrum of genomic changes and novel regulatory interactions (Wendel, 2015), at least some of which are likely to facilitate phenotypic innovation and be relevant to cotton evolution and cotton fiber improvement (Otto, 2007; Wendel et al., 2010; Renny‐Byfield et al., 2016). Transcriptomic analyses have demonstrated that in both G. hirsutum and G. barbadense, > 20% of genes show subgenome‐biased expression in specific tissues (Yoo & Wendel, 2014; Liu et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015), but little is understood regarding the molecular basis of differential homoeologous gene expression.

In the present study, we characterize a basic Helix‐Loop‐Helix (bHLH) factor, PRE1 (PACLOBUTRAZOL RESISTANCE 1) from G. hirsutum (Gh), which we observed to be preferentially expressed in fiber cells. The bHLH proteins constitute a large family of transcription factors in eukaryotes (Zhiponova et al., 2014). Typically, a bHLH domain harbors two functional regions, the N‐terminal basic region responsible for DNA binding, and the C‐terminal HLH region which mediates the formation of either homo‐ or heterodimers of bHLH proteins (Wang et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Oh et al., 2014). In addition, some members of the family are atypical in lacking the DNA‐binding basic region; these are thought to mediate the activities of other transcription factors through protein–protein interactions (Wang et al., 2009). Among atypical bHLHs, members of the inhibitor of DNA binding/differentiation (Id) in animals (Ling et al., 2014) and the paclobutrazol resistance (PRE) family in plants are well‐characterized (Bai et al., 2012; Zhiponova et al., 2014). The PREs are mostly small proteins composed of 90–110 amino acid residues, with highly conserved HLH domains but other, more variable regions. The Arabidopsis thaliana PRE1 was first identified from a mutant insensitive to paclobutrazol (PAC), a GA biosynthesis inhibitor, and promotes elongation of hypocotyl cells (Lee et al., 2006). Another PRE of Arabidopsis, PRE6, was also reported to stimulate hypocotyl growth (Hyun & Lee, 2006).

Here, we assess the function of GhPRE1 in promoting fiber elongation and describe the evolution of the PRE1 promoter and its possible relationship to the long‐fiber phenotype. We show that in fibers of most of the allopolyploid cotton species, only the A‐subgenome copy is expressed, which provides evidence that variation in the TATA‐box region is the primary factor behind the differential homoeologous PRE1 expression in allotetraploid cottons. This is the first demonstration of a molecular mechanism that underlies differential homoeolog expression in cotton, potentially connecting homoeolog bias to an important plant phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The authorities for all of the cotton species under our investigation include: the Institute of Plant Physiology and Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China; the National Wild Cotton Nursery, China; Nanjing Agriculture University, China; and Iowa State University, USA.

Cotton species used include the allopolyploid species Gossypium hirsutum (Gh; 33 accessions of G. hirsutum were used; see Supporting Information Table S1); G. barbadense; G. tomentosum; G. mustelinum; G. darwinii; G. ekmanianum; the two A‐genome diploids G. herbaceum and G. arboretum; the D‐genome species closest to the Dt genome donor, G. raimondii; and 17 other diploid species from across the genus (with one outgroup, Thespesia populnea), as listed in Table S1. These wild diploid and allopolyploid Gossypium materials were obtained from the National Wild Cotton Nursery of Cotton Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Sanya, Hainan, China.

Plants of G. hirsutum cv R15 and its transgenic lines were grown in the glasshouse at 28 ± 2°C under a 14 h : 10 h, light : dark photoperiod, and in the field in Songjiang (Shanghai), Anyang (Henan Province) and Sanya (Hainan Province). Gossypium barbadense cv Xinhai 21, G. darwinii, G. arboreum and G. herbaceum were also cultivated. The rest of the species were collected from the cotton nursery in Sanya and Nanjing Agriculture University, China, or from Iowa State University, USA. Ovules were harvested at different growth stages as indicated in Figs 1 and (see later) 3 and 5, and fibers were isolated by scraping the ovule in liquid nitrogen. Plants of Nicotiana benthamiana and Arabidopsis thaliana (Col‐0) were grown at 28 ± 2°C or 22 ± 2°C, respectively, under a 16 h : 8 h, light : dark photoperiod.

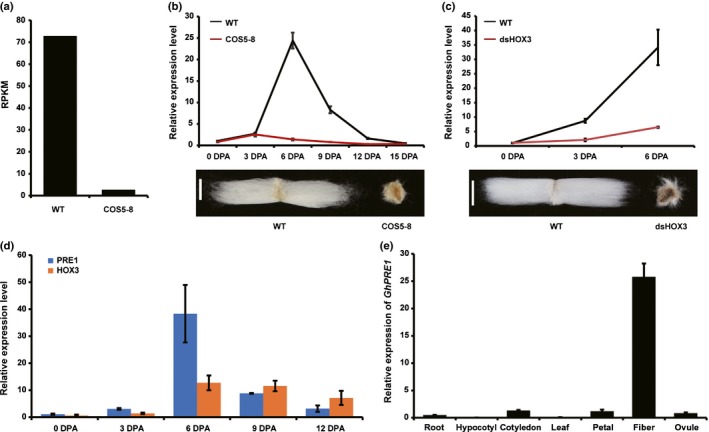

Figure 1.

Gossypium hirsutum PACLOBUTRAZOL RESISTANCE 1 (GhPRE1) is highly expressed in cotton fiber cells during elongation. (a) GhPRE1 transcript abundance in the transcriptome of the 6‐d post‐anthesis (DPA) cotton fiber of Gossypium hirsutum, which was greatly reduced in the 35S::GhHOX3 co‐suppression line (COS5‐8) compared to wild‐type (WT). RPKM, reads per kilobase per million mapped reads. (b, c) Expression of GhPRE1 in cotton fiber cells during elongation, which was nearly completely repressed in (b) COS5‐8 and (c) 35S::dsGhHOX3; bars, 1 cm. (d) Expressions of GhPRE1 and GhHOX3 in cotton fiber cells, which show similar dynamic patterns during fiber elongation and a peak at c. 6 DPA. (e) Expression of GhPRE1 in different cotton tissues, showing a high specificity to cotton fiber. From (b–e), the relative transcript levels were analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT‐PCR), with cotton histone‐3 (AF024716) as the internal reference. Error bars indicate ± SD (n = 3).

Plant transformation and phenotypic analysis

The open reading frame (ORF) of PACLOBUTRAZOL RESISTANCE 1 (GhPRE1) was PCR‐amplified from a G. hirsutum cv R15 fiber cDNA library with PrimeSTAR HS DNA polymerase (Takara Biomedical Technology Co. Ltd, Beijing, China) and inserted into the pCAMBIA 2301 vector to construct 35S::GhPRE1A and RDL1::GhPRE1A. For 35S::dsPRE1, sense and antisense GhPRE1A fragments, separated by a 120‐bp intron of the RTM1 gene from A. thaliana, were cloned into pCAMBIA2301. Primers used in this investigation are listed in Table S2.

The binary constructs were transferred into Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Plants of A. thaliana were transformed with a flower dip method (Bent, 2006). Cotton transformation was performed as described previously (Shangguan et al., 2008). Briefly, hypocotyl segments of the 5‐ to 7‐d‐old cultivated G. hirsutum cv R15 seedlings were used as explants for A. tumefaciens infection, calluses were induced and proliferated, and plantlets were then regenerated. Transgenic cotton plants were grown in glasshouse or field. For T0 and subsequent generations, β‐glucuronidase (GUS) histochemistry staining and PCR were carried out to identify the transgenic lines. To measure fiber length, 30 seeds each plant were harvested at random, fibers were swept to two sides by a comb and length was measured with a ruler (Figs 1, 2).

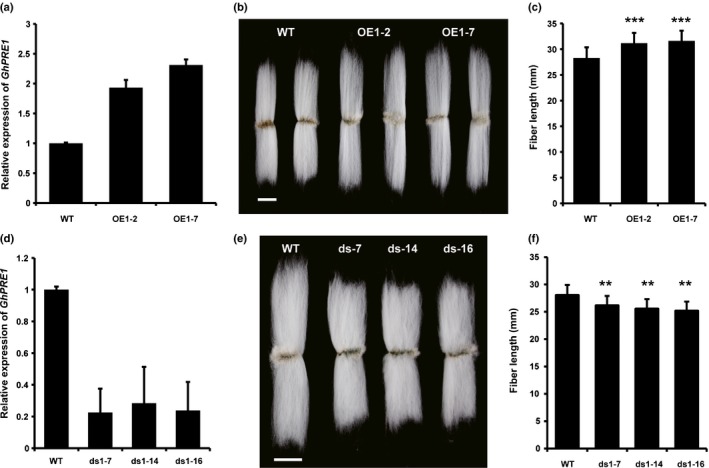

Figure 2.

Gossypium hirsutum PACLOBUTRAZOL RESISTANCE 1 (GhPRE1) promotes cotton fiber elongation. (a–c) Expression of GhPRE1 in 6‐d post‐anthesis (DPA) fibers in (a) the RDL1::GhPRE1 overexpression (OE) lines, their fiber (b) phenotypes and (c) length compared to wild‐type (WT). (d) Expression of GhPRE1 in three RNAi (35S::dsGhPRE1) lines, (e) their fiber phenotypes and (f) length. Expression was analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT‐PCR); error bars indicate SD (n = 3). Bars, 1 cm. Fiber length data were analyzed by Student's t‐test compared to WT: **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001). Error bars represent SD. (n = 30).

Fiber quality measurements

The fiber quality parameters, including fiber length, fiber strength, micronaire and spinning consistency, were measured at the Cotton Fiber Quality Inspection and Test Center of the Ministry of Agriculture (Anyang, China) with an HVI 900 instrument (Uster Technologies, Shanghai, China).

Nucleic acid isolation and gene expression analysis

Genomic DNA of different cotton species was isolated using a cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) extraction solution (2% CTAB, 0.1MTris, 20 mM EDTA, 1.4M NaCl, pH = 9.5), as described (Stewart & Via, 1993). For RNA extraction, the samples were ground in liquid nitrogen and total RNAs were extracted using the RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen Biotech Co. Ltd, Beijing, China). The coding sequence of cotton PRE1 (GhPRE1A) was cloned by 5′‐ and 3′‐RACE according to the manufacturer's instructions (TaKaRa). Total RNAs of 1 μg were used for cDNA synthesis with oligo (dT) primers and M‐MLV (Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus) Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). The products were diluted 10‐fold before analysis. Quantitative real‐time PCR was performed with SYBR‐Green PCR Mastermix (TaKaRa), and amplification was real‐time monitored on a cycler (Mastercycler RealPlex; Eppendorf Ltd, Shanghai, China). Cotton histone‐3 gene (GhHIS3, AF024716) was used as the internal reference. Transcriptome analysis of expressions is based on the previously generated data (Shan et al., 2014; Yoo & Wendel, 2014; Zhang et al., 2015).

Microscope observation

A 35S::GhPRE1A‐VENUS in pCAMBIA2301 vector was constructed to determine subcellular localization of the protein. Agrobacterium cells containing the plasmid were infiltrated into the abaxial side of N. benthamiana leaves by using a syringe for transient expression. The infiltrated areas were harvested 72 h later and observed under a confocal microscope (LSM510, Zeiss). Hypocotyl epidermal cells of A. thaliana were wet‐mounted and observed under an optical microscope.

Sequence polymorphism analysis

The genomic sequence of PRE1 was first cloned from G. hirsutum cv R15 by using the Genome Walking kit (TaKaRa). PRE1 locus was re‐examined by local blast with the reported genome sequence data (Wang et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015) using the software BioEdit (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/bioedit/bioedit.html). The genomic sequence of PRE1 and a 3‐kb upstream sequence flanking to this locus (Table S3) were picked for further analysis. For diploid and allotetraploid cotton species whose genome sequences were unavailable, the PRE1 gene fragment was obtained by PCR, followed by insertion into the PMD18‐T vector for sequencing. The sequences in different Upland cotton (G. hirsutum) or extra‐long staple (ELS) cotton (G. barbadense) cultivars were obtained from the reported data (Fang et al., 2017a).

The software Vector NTI was used to align PRE1 sequences. Homoeologous comparisons were conducted between A and D subgenomes in polyploids. Mega 7 software (http://megasoftware.net/) was used to construct phylogenetic trees with maximum‐likelihood estimation and 1000 bootstrap resamplings.

Pyrosequencing

GhPRE1A was amplified from the fiber cDNA library of G. hirsutum cv R15 and inserted into the pMD18‐T vector. For GhPRE1D, the predicted cDNA was synthesized and inserted into the pUC57 vector (Sangon Biotech Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China). Artificial mixtures were generated by adding the PCR products of the two genes in a series of defined ratios as shown in Fig. S1(a), and subjected to pyrosequencing (Schaart et al., 2005; Wang & Elbein, 2007) (Sangon Biotech). For expression analysis in vivo, cDNAs were generated by reverse transcription of total RNAs with oligo (dT) primers and subject to pyrosequencing. The relative expression levels of PRE1 were determined by using primers list in Table S2.

Promoter activity analysis

The 0.7‐kb promoter fragments of PRE1 were amplified from G. hirsutum cv R15 genomic DNA and inserted into the luciferase reporter. The deletion of the TATA‐box from the GhPRE1A promoter and its insertion in the GhPRE1D promoter were performed by overlapping PCR with the primers listed in Table S2. The plasmids were transferred into A. tumefaciens, together with a co‐suppression repressor plasmid, pSoup‐P19. The transformed cells were collected and were infiltrated into the abaxial side of N. benthamiana leaves with a syringe. The infected areas were harvested 3 d later for extraction of total proteins, which were analyzed by using the kit Dual‐Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega; E1910). The fluorescent values of firefly luciferase (LUC) and Renilla (REN) luciferase were detected with Promega GloMax 20/20, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The value of LUC was normalized to that of REN. Promoter activities in cotton fiber cells were determined by transient expression of a green fluorescence protein reporter. The 0.7‐kb promoter fragments of GhPRE1 were fused to the coding region of a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter in pCAMBIA2301 (Fig. S2a). The plasmids were transformed into ovules (1DPA) by helium‐driven particle accelerator (PDS‐1000; Bio‐Rad). The ovules were incubated for 24 h at 30°C in the dark before observation of GFP signal in fiber cells under a confocal laser scanning microscopy (LSM510; Zeiss).

Results

PRE1 promotes cotton fiber elongation

The homeodomain leucine zipper (HD‐ZIP) IV transcription factor GhHOX3 is a key regulator of cotton fiber elongation, as demonstrated by the fact that both 35::GhHOX3 transgene co‐suppression (COS5‐8) and 35S::dsGhHOX3 RNA interference (RNAi) lines of G. hirsutum produce shorter, fuzzier fibers (Shan et al., 2014). Transcriptome comparisons revealed that one of the PRE family genes, GhPRE1, was markedly downregulated in COS5‐8 cotton fiber (Fig. 1a). Analysis by real‐time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT‐PCR) confirmed its downregulation following GhHOX3 silencing and indicated its high expression in fiber cells during 6–9 d post‐anthesis (DPA) when the fiber underwent rapid elongation (Fig. 1b,c). The similar expression pattern shared with GhHOX3 (Fig. 1d) and the highly specific expression in fiber cell (Fig. 1e) suggest that PRE1 may function in modulating fiber cell elongation.

Transient expression assays with tobacco leaf cells localized the fusion protein of GhPRE1A‐VENUS (the letter after the gene name denotes genome or subgenome) to the nucleus and the plasma membrane (Fig. S3a). When introduced into A. thaliana, seedlings overexpressing GhPRE1A produced longer hypocotyls and roots (Fig. S3b–e), demonstrating that cotton PRE1 functions in a similar way to Arabidopsis homoeologs in promoting cell elongation (Lee et al., 2006).

In order to provide direct evidence of GhPRE1 function in cotton, we engineered G. hirsutum for overexpression and suppression. The promoter of cotton RDL1 gene is strong and fiber/trichome‐specific (Wang et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2013). When GhPRE1A was expressed in transgenic G. hirsutum under the control of the RDL1 promoter, the transcript levels increased in fiber cells (Fig. 2a) and the RDL1::GhPRE1A lines produced longer fibers compared to the untransformed control (Fig. 2b,c). Apart from mature fiber length, other fiber quality parameters of the overexpression lines, such as strength and micronaire, were also improved (Table 1). On the contrary, suppressing GhPRE1 expression by RNAi resulted in shorter fibers (Fig. 2d,e,f). Although the difference was notable and significant, the fiber length reduction was not as severe as that caused by GhHOX3 silencing (Shan et al., 2014), probably due to insufficient knockdown and functional redundancy of PRE family members. Together, these data indicate that GhPRE1 is highly and preferentially expressed in cotton fiber cells where it acts as a positive regulator of cell elongation.

Table 1.

Fiber quality parameters of the wild‐type (WT) and the Gossypium hirsutum PACLOBUTRAZOL RESISTANCE 1 (GhPRE1) overexpression (OE) cotton lines

| Genotype | Len | Str | Mic | SCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 30.05 ± 0.35 | 28.6 ± 0.98 | 4.85 ± 0.07 | 147.50 ± 0.71 |

| OE1‐2 | 32.55 ± 0.63 | 29.75 ± 0.35 | 4.40 ± 0.28 | 154.00 ± 2.82 |

| OE1‐7 | 32.75 ± 0.49 | 31.25 ± 0.07 | 4.40 ± 0.01 | 162.00 ± 7.07 |

Len, length; Str, strength; Mic, micronaire; SCI, spinning consistency. Error values indicate ± SD (n = 3).

Expression of PRE1 in cottons is related to long fiber formation

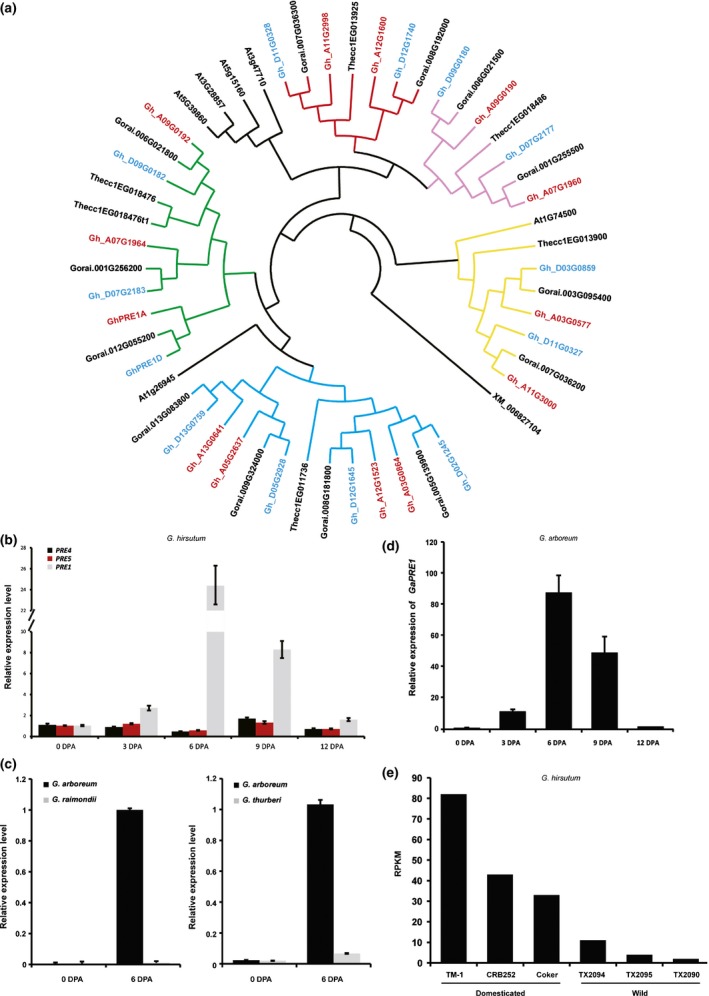

Changes in seed‐born trichome length are characteristic of cotton species. There are four cotton species domesticated for spinnable fiber, among which two (G. hirsutum and G. barbadense) are AtDt allotetraploids and two (G. herbaceum and G. arboreum) are A‐genome diploids. Although G. hirsutum generally is grown for its high fiber yield, G. barbadense produces ELS fibers for upmarket textiles. Our previous BLAST search with Arabidopsis PRE queries identified 13 PRE genes in G. raimondii, the best extant model of the D‐genome progenitor, and recovered all 26 predicted orthologs – 13 in each subgenome – in G. barbadense (Liu et al., 2015). The G. hirsutum genome also harbors the same expected 26 PRE genes (Fig. 3a). Although transcripts of several PRE genes were detected in G. hirsutum fiber, GhPRE1 was predominant with regard to their mRNA levels (Figs 3b, S4a), which further suggests that GhPRE1 is specialized to function in regulating cotton fiber elongation.

Figure 3.

PACLOBUTRAZOL RESISTANCE 1 (PRE1) expression associates with spinnable cotton fiber formation. (a) Phylogenetic analysis of PRE genes in Theobroma cacao (Thecc), Arabidopsis thaliana (At), Gossypium raimondii (Gorai) and G. hirsutum (Gh) by the maximum‐likelihood on nucleotide sequences. Subfamilies are denoted by different colors, with PRE1 being in the red clade. GhPRE1A/D, Gh_A05G3166_5/Gh_D04G0454; GhPRE2A/D, Gh_A12G1523/Gh_D12G1645; PRE3A/D, Gh_A03G0864/Gh_D02G1245; PRE4A/D, Gh_A07G1964/Gh_D07G2183; PRE5A/D, Gh _A09G0192/Gh_D09G0182; PRE6A/D, Gh_A03G0577/Gh_D03G0859; PRE7A/D, Gh_A05G2637/Gh_D05G2928; PRE8A/D, Gh_A07G1960/Gh_D07G2177; PRE9A/D, Gh_A09G0190/Gh_D09G0180; PRE10A/D, Gh_A11G3000/Gh_D11G0327; PRE11A/D, Gh_A11G2998/Gh_D11G0328; PRE12A/D, Gh_D12G1740/Gh_A12G1600; PRE13A/D, Gh_A13G0641/>Gh_D13G0759. The PRE ortholog from Amborella trichopoda (XM_006827104) was used as outgroup. (b) Expression of GhPRE genes in cotton fibers at different numbers of days post‐anthesis (DPA), as indicated, GhPRE1 is the major PRE gene expressed in cotton fiber. (c) Expression of PRE1 orthologs in fibers of the A‐genome species G. arboreum compared to two D‐genome species: left, G. raimondii, the model progenitor diploid to allopolyploid cottons, and right, G. thurberi, a phylogenetically more distant D‐genome species. (d) Expression of PRE1 orthologs in the A‐genome G. arboreum fibers during the fast elongation stage. The transcripts were analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT‐PCR); error bars indicate SD (n = 3). (e) Expression levels of GhPRE1 in domesticated G. hirsutum cultivars and wild relatives, based on transcriptome data of 10‐DPA fiber. RPKM, reads per kilobase per million mapped reads.

We then extended the expression analysis of PRE1 to other cotton species. Analysis by qRT‐PCR showed that PRE1 expression was undetectable in seeds of G. raimondii, or in other diploid species that do not bear long fibers, such as G. thurberi (Fig. 3c). However, the A‐genome G. arboreum (Fig. 3c,d), as well as three other fiber‐bearing allotetraploid cottons (G. barbadense, G. darwinii and G. tomentosum), all showed a clear expression of PRE1 in fiber cells at the mid‐elongation stage (Figs S4b–d, 3). These data suggest that PRE1 has probably acquired its expression in cotton seed trichomes along with long fiber evolution.

Furthermore, the correlation between PRE1 expression and cotton fiber elongation is not limited to the interspecies level, because domesticated cultivars of G. hirsutum exhibit higher transcript levels than their respective non‐domesticated races (Fig. 3e), suggesting that the PRE1 expression levels in fiber cells have been under selection during the course of domestication and crop improvement for longer fiber.

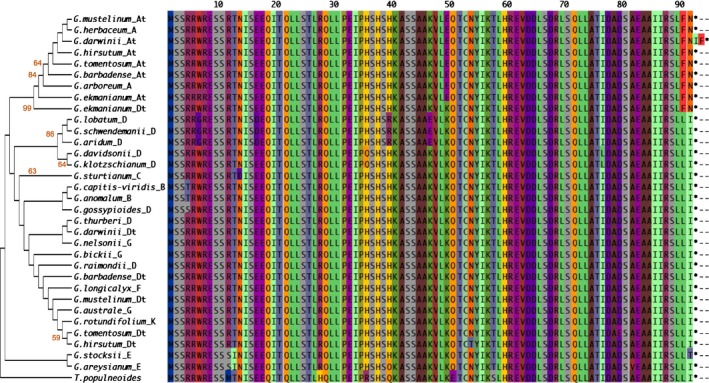

PRE1 sequence variation

We aligned homoeologous regions of PRE1 coding sequence and its flanking regions from all diploid and allopolyploid species surveyed (Table S1). Gene structure was highly conserved among all species, with two exons of 40 and 51 amino acid residues, separated by an intron of 70 (PRE1D from G. hirsutum and G. ekmanianum) or 74 (all other species) nucleotides (Figs 4, 5a). PRE1 nucleotide sequences also are highly conserved in the genus, with 13 and 16 polymorphic sites in Exons 1 and 2, respectively, corresponding to an average of three amino acid differences between each pair of sequences, and a maximum difference of eight amino acids between members of the D and E genome (Figs 4, 5a). Not surprisingly, phylogenetic analysis of the protein sequences led to trees that were incompletely resolved due to strong sequence conservation, yet sequences from related species generally fell into the same clades (Fig. 4). Interestingly, the alignments suggest historical evidence for interhomoeolog gene conversion, as has been reported for other cotton genomic regions (Salmon et al., 2010; Wang & Paterson, 2011). Specifically, the Dt homoeolog from the 3′ end of exon 2 in G. ekmanianum displayed a conversion track such that its inferred amino acid sequence contained two sequential residues that are otherwise restricted to the At homoeologs of all other allopolyploid species (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree and protein sequences of cotton PACLOBUTRAZOL RESISTANCE 1 (PRE1). The phylogenetic relationship of 32 cotton PRE1 protein sequences (from 20 diploid and six allotetraploid species) was inferred by using MEGA and the maximum‐likelihood method based on the Jones–Taylor–Thornton (JTT) model with 1000 bootstrap replications. Percentage bootstrap scores of > 50% were displayed. Notice the putative gene conversion at positions 90 and 91 in the At homoeolog of Gossypium ekmanianum. The letter(s) after the species name denotes the genome or subgenome group, Thespesia populnea PRE1 was used as outgroup.

Figure 5.

Subgenome‐biased expression of PACLOBUTRAZOL RESISTANCE 1 (PRE1) in allotetraploid cottons. (a) Schematic representation of PRE1 gene and nucleotide polymorphisms in the coding region of PRE1 homoeologs (PRE1A and PRE1D) in allotetraploid cottons. P1 and P2 indicate locations of primers used in pyrosequencing. The single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) used for genotyping the homoeologous pair are indicated by underlining. Identical sequences are not shown. (b–d) PRE1 shows a striking expression bias toward the At homoeolog in ovules and fibers of (b) Gossypium hirsutum, (c) G. barbadense and (d) G. darwinii. (e) Both At and Dt copies of PRE1 were expressed in ovules and fiber cells of G. tomentosum, a wild allotetraploid cotton species endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. All pyrosequencing assays were repeated three times with similar results, and representative results are shown. The routine technical error of pyrosequencing is c. 5%. DPA, days post‐anthesis.

Subgenome bias of PRE1 expression in allotetraploid cottons

Homoeologous genes may express unequally in a tissue, a phenomenon called expression bias (Yoo et al., 2013). Considering that allotetraploid cottons originated from hybridization between the A‐ and D‐genome progenitors c. 1–2 Myr ago (Wendel, 1989; Small et al., 1998; Wendel & Cronn, 2003; Paterson et al., 2012; Wendel & Grover, 2015), we asked whether the At and Dt homoeologs of PRE1 are expressed equally. We further addressed whether expression in allotetraploid cotton fiber has been altered by polyploidization or if instead the patterns observed reflect simple descent from conditions found in their diploid ancestors.

The two PRE1 homoeologs in G. hirsutum, GhPRE1A and GhPRE1D, share 97% of nucleotide acids in the coding region and 96% amino acid sequence identities. To distinguish between them, we first screened for subgenome‐specific DNA polymorphisms in a series of Gossypium accessions. All PRE family genes identified so far, including cotton PRE1, have a similar gene architecture with two exons separated by an intron (Fig. 5a). Among the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) detected, two are located in the second exon (Fig. 5a, underlined). Pyrosequencing of the fragment harboring the two SNPs accurately mirrors the relative amounts of the homoeologous copies in an artificial mixture of GhPRE1A and GhPRE1D (Fig. S1a). Subsequent analysis of several allotetraploids, including the cultivated G. hirsutum and G. barbadense, as well as the wild G. darwinii and G. mustelinum, revealed a striking bias favoring A‐subgenome PRE1 expression in the ovule and fiber: although the PRE1A transcripts were readily detected, the Dt counterparts were undetectable (Figs 5b–d, S1b). However, in G. tomentosum, a wild allotetraploid cotton which produces inferior fibers (Fig. S5), this bias is not evident, or even is reversed, with higher expression of the Dt homoeolog (Fig. 5e). We note also that fibers from G. darwinii and G. mustelinum also are relatively short, much like those of G. tomentosum, yet as mentioned PRE1 is highly biased toward the At homoeolog in these species. These observations collectively suggest that high PRE1 expression may be necessary but not sufficient for generating highly elongated fiber cells. These expression variations prompted us to further scan polymorphisms in the PRE1 gene, including the flanking sequences.

TATA‐box deletion is behind the biased PRE1 expression

It is well known that cis regulatory elements are critical to gene expression and gene expression evolution (Wittkopp & Kalay, 2012). In this light, the strongly biased expression of PRE1 in allotetraploid cottons suggests a possible presence of intersubgenomic polymorphisms in cis‐acting elements that confer the At PRE1 expression bias, or inactivate the Dt homoeolog (with the exception of G. tomentosum).

In order to map the sequence variations, we performed comparisons of a c. 3‐kb genomic fragment spanning the PRE1 locus (Fig. S6; Table S3). We found that one variation perfectly correlates with PRE1 expression; in the five allotetraploids with PRE1A‐biased expression, the silent D‐subgenome PRE1D invariably has an 11‐bp deletion in the promoter region; in G. tomentosum, however, which does not show PRE1A bias, both homoeologs are intact in this region (Fig. 6a,b). Strikingly, this 11‐bp fragment contains a canonical TATA‐box (5′‐TATAAA‐3′) (Patikoglou et al., 1999), which is located 31 nucleotides (nt) upstream to the transcriptional start site (TSS) determined by rapid‐amplification of cDNA (Fig. 6a,b); we term this fragment PRE1‐TATA. Furthermore, an analog of the transcription factor IIB‐recognition element (BREd) (Deng & Roberts, 2007) is present four nucleotides downstream of PRE1‐TATA (Fig. 6a), which further supports it as a genuine TATA‐box. We further noted that all other diploid Gossypium species studied, as well as the phylogenetic outgroup Thespesia populnea, have an intact PRE1‐TATA (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6.

TATA‐box mediates PACLOBUTRAZOL RESISTANCE 1 (PRE1) promoter activity. (a) Sequence of Gossypium hirsutum GhPRE1A core promoter fragment. TSS, transcriptional start site. BRE d, downstream transcription factor IIB‐recognition element. (b) PRE1 core promoter fragments of 32 cotton and the outgroup (Thespesia populnea), as in Fig. 4. Promoter sequences of 33 cotton PRE1 genes were aligned; dashes indicate deletions and dots represent identical nucleotides. The 11‐bp TATA‐box was absent in Dt homoeologous PRE1 promoters of five allotetraploid species but present in G. tomentosum. (c) Schematic map of GhPRE1A (At) and GhPRE1D (Dt) promoter‐luciferase reporters, in which the TATA‐box fragment was intact, deleted or added. (d) Activities of the promoters in (c), determined by transient expression of a luciferase reporter in tobacco leaves; the value of blank (bottom in c) was set to 1. Data were analyzed by one‐way ANOVA compared to the GhPRE1A promoter (At): **, P ≤ 0.01. Error bars represent SD (n = 3).

TATA‐box is a core promoter element mediating transcriptional machinery assembling, which in turn directs gene expression (Tirosh et al., 2006). Our analysis has revealed that the PRE1‐TATA deletion might be the causal agent for homoeolog‐specific PRE1 silencing in allotetraploids. To assay the role of PRE1‐TATA in gene expression, we cloned the promoter fragments of GhPRE1A and GhPRE1D, and used these to drive a firefly LUC reporter gene (Fig. 6c) in tobacco cells and GFP in cotton fiber cells (Fig. S2a), respectively. Consistent with the biased expression pattern in cotton fiber (Fig. 5b–d), the GhPRE1A promoter conferred constantly higher reporter activity in tobacco cells than did the GhPRE1D promoter (Fig. 6d). Furthermore, deleting the PRE1‐TATA from the GhPRE1A promoter was sufficient to reduce reporter activity substantially, and conversely, adding the TATA back to the GhPRE1D promoter restored its activity to the level of GhPRE1A (Fig. 6d). Consistently, activity of the GhPRE1A promoter in cotton fiber cells was greatly reduced when the PRE1‐TATA was removed (Fig. S2b,c). Clearly, PRE1‐TATA is indispensable for high PRE1 promoter activity.

Modifications of cis‐elements often lead to expression changes in spatial patterns or transcription levels of genes, and this is a key mechanism of adaptive evolution (Wray, 2007; Carroll, 2008; Grover et al., 2012; Wittkopp & Kalay, 2012; Lemmon et al., 2014). To examine the correlation between the PRE1 TATA‐box variation and cotton fiber phenotypes, we surveyed 163 accessions of diploid and allotetraploid cottons including wild species, semi‐wild and domesticated races of distinct geographical origins (Tables S1, S4). The canonical TATA‐box element is present in the PRE1 promoter of all 20 representative diploid cotton species of different genome types surveyed (Fig. 6b). However, as noted above, PRE1‐TATA is deleted from PRE1D of five of the six allopolyploid species studied, the exception being G. tomentosum in which it is present (Figs 5e, 7).

Figure 7.

A schematic representation of the TATA‐box indel in D‐subgenome PACLOBUTRAZOL RESISTANCE 1 (PRE1) of allotetraploid cotton species and the association of PRE1A expression with spinnable fiber formation. In the cotton genus (Gossypium), the PRE1 gene in all diploid species studied has a canonical TATA‐box in the core promoter. Shortly after allotetraploid (AtDt) formation c. 1–2 Myr ago (Ma), a 11‐bp fragment containing the TATA‐box (TATA) of the Dt homoeologous PRE1 (PRE1D) was deleted in the nascent allotetraploid, which was transmitted to its descendants, including most present day wild allotetraploid cotton species. In G. tomentosum, however, the TATA‐box was reinserted, possibly through intersubgenomic conversion from the At homoeolog. High expression of PRE1A in diploid and allopolyploid cottons is associated with long spinnable fibers. The drawings below the A genome and the polyploid groups represent cotton fibers (left) and expression of PRE1 homoeologs (right).

Thus, G. tomentosum lacks the expression bias (Fig. 5e) and also the PRE1D TATA deletion (Fig. 6b). These two observations are not independent, as the TATA‐box is indispensable for PRE1 promoter activity (Fig. 6c,d). It may be that, in this species, for reasons that are unclear, the two homoeologs are under strong trans‐regulation, thereby upregulating both the At and Dt PRE1 genes. From a phylogenetic perspective, accumulated evidence indicates that this Hawaiian Islands endemic is not basal within the polyploid clade, but that it is instead nested within the polyploids in a position close to the G. hirsutum clade (Grover et al., 2012, 2015). Thus, the manner in which G. tomentosum acquired an intact as opposed to deleted TATA element in its Dt homoeolog is of interest. One possibility is that it reflects simple inheritance from the D‐genome diploid ancestor, but this would require independent loss of the TATA element in at least two other allopolyploid lineages and at identical positions; thus we view this scenario as unlikely. A second alternative related to this first idea is that of vertical inheritance from the D‐genome diploid ancestor but that the true phylogeny differs from that presently indicated by a wealth of data (Grover et al., 2012, 2015); we view this scenario as equally unlikely. A final possibility is that of ‘gene conversion’; that is, nonreciprocal homoeologous exchange involving physical contact of the two homoeologs, such that the indel was ‘corrected’ by the PRE1A copy (Fig. 7). Interhomoeolog exchange has been described in cotton previously (Salmon et al., 2010; Flagel et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2014), and we note other evidence for this process affecting PRE1 genes elsewhere in this paper (see discussion of G. ekmanianum, in the results). If, indeed, G. tomentosum acquired its PRE1D TATA element via gene conversion, the converted region was quite small, as it remains flanked by diagnostic D‐genome‐specific SNPs (Fig. 6b).

Discussion

PACLOBUTRAZOL RESISTANCE (PRE) proteins in plants function via protein–protein interactions and act as a hub integrating multiple signaling pathways to regulate cell growth and development (Lee et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Schlereth et al., 2010). In addition, PRE genes themselves are also regulated by phytohormones, such as gibberellic acid (GA) (Park et al., 2013). Our previous investigation showed that the homeodomain leucine zipper (HD‐ZIP) IV transcription factor Gossypium hirsutum (Gh) GhHOX3 is a core regulator of cotton fiber elongation, it interacts with other HD‐ZIP IV factors, leading to enhanced transcriptional activation of downstream genes, including GhRDL1 and GhEXPA1, which promote cell wall loosening (Wang et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2013). The GA signaling repressor DELLA interferes with this process through competitive binding to GhHOX3, thus transducing GA signal to cotton fiber growth (Shan et al., 2014). Similar interaction also functions in Arabidopsis in mediating hypocotyl epidermal cell growth (Rombola‐Caldentey et al., 2014), suggesting that this is a general mechanism that promotes plant cell growth.

In the present investigation, we identified GhPRE1A from the GhHOX3 co‐suppression lines and its expression was repressed following GhHOX3 silencing. However, the GhPRE1 promoter does not contain an L1 cis‐element recognized by HD‐ZIP IV factors, and thus the repression may be an indirect effect of GhHOX3. Similar to the positive role of reported PREs in plant cell growth (Hyun & Lee, 2006; Lee et al., 2006), GhPRE1 acts as a positive regulator of cotton fiber elongation, but whether its function involves the GhHOX3‐DELLA complex is not clear at this time. One possibility is that it acts in bridging hormone (such as GA and brassinosteroid (BR)) signaling and the cell autonomous pathways to control fiber cell growth.

Phenotypic novelty in evolution, resulting from either natural or under strong directional human selection, can target coding regions or variation in regulatory elements (Wray, 2007; Carroll, 2008; Wittkopp & Kalay, 2012; Lemmon et al., 2014). One example is of an insertion of a TATA‐box in the promoter of an Iron‐Regulated Transporter1 (IRT1) gene in apples, leading to enhanced tolerance to iron (Zhang et al., 2016). A second relevant example involves tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum), which are cross‐pollinated with long exerted stigmas in the wild but have included stigmas in cultivated forms (Rick et al., 1977; Chen et al., 2007). Stigma length is controlled by Style2.1, which encodes a PRE‐like protein, and it is the novel presence of two indels in the promoter that reduced Style2.1 expression in domesticated tomatoes (Chen et al., 2007).

Cotton PRE1 also varies in its promoter sequence, with a fragment deletion directly removing the core regulatory element, the TATA‐box. In allotetraploid cottons, deletion of the TATA‐box in the D‐subgenome PRE1 silenced its expression, resulting in A‐subgenome‐specific expression. Notably, in G. raimondii, the closest D‐genome progenitor species with short fibers, PRE1 expression levels are low in ovules, whereas PRE1 is highly expressed in fiber cells in the allopolyploids and the diploid A‐genome cottons. Thus, high PRE1 expression in fiber is a characteristic both of some diploids and of all allopolyploids. It seems likely from the evidence presented here that at the time of initial polyploidization, the highly expressed PRE1A inherited from the A‐genome parent may have helped stimulate fiber elongation in nascent allotetraploid cottons, which thereby acquired an expression bias toward the parental A‐subgenome PRE1, whereas the Dt homoeolog was further silenced as a result of the TATA‐box deletion from its promoter (Fig. 7). The exception, observed in G. tomentosum, is most likely due to interhomoeolog gene conversion from the A‐ to D‐ PRE1 homoeolog after diversification of the primary allotetraploid cotton lineages. Subsequently, and in parallel in the two‐cultivated species G. barbadense and G. hirsutum, expression levels became enhanced as a consequence of the domestication process (Fig. 7). Probably not coincidently, variations in the PRE gene regulatory elements are closely related to key agronomic traits in both tomato and cotton, which suggests a recurring role of PRE gene expression patterns in crop evolution.

The widely cultivated upland cotton G. hirsutum and the high‐quality extra‐long staple (ELS) cotton G. barbadense have experienced a relatively long history of evolution following the merger of two sets of genomes. Transcriptome sequencing has repeatedly demonstrated that a high fraction (often 20–40%) of genes in G. hirsutum exhibit A‐ or D‐subgenome biased expression (Yoo & Wendel, 2014; Liu et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015). In particular, in G. hirsutum the myeloblastosis (MYB)‐MIXTA‐like transcription factor gene GhMML4 (GhMML4_D12), a key regulator of lint (spinnable fiber) development, shows a strong subgenome‐biased expression (Wu et al., 2018). We speculate that that selection has shaped gene expression variation through its action on underlying variation in multiple regulatory elements throughout the genome. The fact that the two progenitor diploid genomes vary two‐fold in size and that they evolved in isolation on different continents for 5–10 Myr, suggests that cis‐element divergence at the diploid level would have been prevalent at the time of initial polyploid formation. With the mounting genome sequences and tools available, extensive comparisons of sequence variations in relation to gene expression patterns will undoubtedly uncover additional examples of the type of evolution and selection described here.

We note that higher expression of PRE1A appears to have evolved in the diploid A‐genome species, in association with the first appearance of long, spinnable fibers (Fig. 3c). Yet this higher expression did not depend solely on the TATA‐box, because this is universally present among the diploid orthologs, including A and D. After AD allotetraploid formation, the TATA deletion from the Dt (tetraploid) homoeolog generated biased expression, raising the question about the functional relevance of the TATA deletion. In this respect we envision two possible scenarios, one neutral and one driven by differential homoeolog selection. Under the neutral scenario, the deletion was not functionally relevant; the PRE1D TATA deletion was inconsequential, perhaps because of the redundancy offered by its PRE1A homoeolog. If instead natural selection favored the PRE1A homoeolog, the deletion may have arisen following selective fixation of a novel TATA deletion in the PRE1D copy, concomitant with or followed by both natural and human‐mediated selection for enhanced PRE1A expression in fibers. As the atypical basic helix‐loop‐helixes exert biological functions in partnership with other transcription factors, finding the GhPRE1 interacting partners holds the key to understand the role of PRE1A in the regulatory network of cotton fiber elongation, which will further help us understand the association of PRE1A high expression with long fiber formation.

Interestingly, overexpression of GhPRE1A in cotton not only promoted fiber elongation, but also improved fiber strength (Table 1). A plausible explanation is that formation of the fiber strength trait involves coordinated cell wall biosynthesis and extension. Given these findings, it will be of interest to explore the relationship between PRE1 expression and fiber length/ strength in other Gossypium species and varieties, particularly inasmuch as there exists considerable infraspecific varietal variation and interspecific differences in fiber length.

Author contributions

B.Z., J.F.W. and X‐Y.C. conceived the research; B.Z., J‐F.C. and Z‐W.C. performed the experiments; B.Z., G‐J.H, J.F.W. L‐Y.W., X‐X.S., Y‐B.M., L‐J.W. and T‐Z.Z. contributed materials and/or analyzed data; X‐Y.C., J.F.W. B.Z., J‐F.C. and G‐J.H. wrote the article.

Supporting information

Please note: Wiley Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any Supporting Information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the New Phytologist Central Office.

Fig. S1 Pyrosequencing of homoeologous PRE1 transcripts of allotetraploid cottons.

Fig. S2 TATA‐box mediates PRE1 promoter activity in cotton fiber cells.

Fig. S3 GhPRE1A promotes cell elongation in Arabidopsis.

Fig. S4 GhPRE1 is expressed in fibers during the fast elongation period in fiber‐producing cotton species.

Fig. S5 View of fibers (seed trichomes) of five allotetraploid cotton species.

Fig. S6 The PRE1 locus in the genomes of four cotton species.

Table S3 The PRE1 loci in reported cotton species

Table S1 Diploid and allotetraploid cottons surveyed in this investigation

Table S2 Primers used in this investigation

Table S4 Distribution of the TATA‐box indel in cotton accessions

Acknowledgements

We thank C‐M. Shan, X‐F. Zhang and D‐Y. Chen for experimental assistance and suggestions, and J‐D. Chen for bioinformatic analysis. We also thank X‐S. Gao in the Core Facility Centre of the Institute of Plant Physiology and Ecology for confocal laser microscopy. This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFD0100500), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31690092, 31788103, 31571251) and the Ministry of Agriculture of China (2016ZX08005‐003).

Contributor Information

Jonathan F. Wendel, Email: jfw@iastate.edu

Xiao‐Ya Chen, Email: xychen@sibs.ac.cn.

References

- Applequist WL, Cronn R, Wendel JF. 2001. Comparative development of fiber in wild and cultivated cotton. Evolution & Development 3: 3–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai MY, Fan M, Oh E, Wang ZY. 2012. A triple helix‐loop‐helix/basic helix‐loop‐helix cascade controls cell elongation downstream of multiple hormonal and environmental signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24: 4917–4929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bent A. 2006. Arabidopsis thaliana floral dip transformation method. Methods in Molecular Biology 343: 87–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll SB. 2008. Evo‐devo and an expanding evolutionary synthesis: a genetic theory of morphological evolution. Cell 134: 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KY, Cong B, Wing R, Vrebalov J, Tanksley SD. 2007. Changes in regulation of a transcription factor lead to autogamy in cultivated tomatoes. Science 318: 643–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W, Roberts SG. 2007. Core promoter elements recognized by transcription factor IIB. Biochemical Society Transactions 34: 1051–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L, Gong H, Hu Y, Liu C, Zhou B, Huang T, Wang Y, Chen S, Fang DD, Du X et al 2017a. Genomic insights into divergence and dual domestication of cultivated allotetraploid cottons. Genome Biology 18: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L, Wang Q, Hu Y, Jia Y, Chen J, Liu B, Zhang Z, Guan X, Chen S, Zhou B et al 2017b. Genomic analyses in cotton identify signatures of selection and loci associated with fiber quality and yield traits. Nature Genetics 49: 1089–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel LE, Wendel JF, Udall JA. 2012. Duplicate gene evolution, homoeologous recombination, and transcriptome characterization in allopolyploid cotton. BMC Genomics 13: 302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher JP, Grover CE, Rex K, Moran M, Wendel JF. 2017. A new species of cotton from Wake Atoll, Gossypium stephensii (Malvaceae). Systematic Botany 42: 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Gong L, Kakrana A, Arikit S, Meyers BC, Wendel JF. 2013. Composition and expression of conserved microRNA genes in diploid cotton (Gossypium) species. Genome Biology and Evolution 5: 2449–2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover CE, Gallagher JP, Jareczek JJ, Page JT, Udall JA, Gore MA, Wendel JF. 2015. Re‐evaluating the phylogeny of allopolyploid Gossypium L. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 92: 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover CE, Grupp KK, Wanzek RJ, Wendel JF. 2012. Assessing the monophyly of polyploid Gossypium species. Plant Systematics and Evolution 298: 1177–1183. [Google Scholar]

- Grover CE, Zhu X, Grupp KK, Jareczek JJ, Gallagher JP, Szadkowski E, Seijo JG, Wendel JF. 2014. Molecular confirmation of species status for the allopolyploid cotton species, Gossypium ekmanianum Wittmack. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 62: 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Wang X, Gundlach H, Mayer KF, Peterson DG, Scheffler BE, Chee PW, Paterson AH. 2014. Extensive and biased intergenomic nonreciprocal DNA exchanges shaped a nascent polyploid genome, Gossypium (Cotton). Genetics 197: 1153–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun Y, Lee I. 2006. KIDARI, encoding a non‐DNA Binding bHLH protein, represses light signal transduction in Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant Molecular Biology 61: 283–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Triplett BA. 2001. Cotton fiber growth in planta and in vitro. Models for plant cell elongation and cell wall biogenesis. Plant Physiology 127: 1361–1366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Lee S, Yang KY, Kim YM, Park SY, Kim SY, Soh MS. 2006. Overexpression of PRE1 and its homologous genes activates Gibberellin‐dependent responses in Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant and Cell Physiology 47: 591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JJ, Woodward AW, Chen ZJ. 2007. Gene expression changes and early events in cotton fiber development. Annals of Botany 100: 1391–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon ZH, Bukowski R, Sun Q, Doebley JF. 2014. The role of cis regulatory evolution in maize domestication. PLoS Genetics 10: e1004745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Fan G, Lu C, Xiao G, Zou C, Kohel RJ, Ma Z, Shang H, Ma X, Wu J et al 2015. Genome sequence of cultivated Upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum TM‐1) provides insights into genome evolution. Nature Biotechnology 33: 524–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Fan G, Wang K, Sun F, Yuan Y, Song G, Li Q, Ma Z, Lu C, Zou C et al 2014. Genome sequence of the cultivated cotton Gossypium arboreum . Nature Genetics 46: 567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling F, Kang B, Sun XH. 2014. Id proteins: small molecules, mighty regulators. Current Topics in Developmental Biology 110: 189–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Zhao B, Zheng HJ, Hu Y, Lu G, Yang CQ, Chen JD, Chen JJ, Chen DY, Zhang L et al 2015. Gossypium barbadense genome sequence provides insight into the evolution of extra‐long staple fiber and specialized metabolites. Scientific Reports 5: 14 139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor S, Paterson AH. 2012. Genomes for jeans: cotton genomics for engineering superior fiber. Trends in Biotechnology 30: 521–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E, Zhu JY, Bai MY, Arenhart RA, Sun Y, Wang ZY. 2014. Cell elongation is regulated through a central circuit of interacting transcription factors in the Arabidopsis hypocotyl . Elife 3: e03031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto SP. 2007. The evolutionary consequences of polyploidy. Cell 131: 452–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Nguyen KT, Park E, Jeon JS, Choi G. 2013. DELLA proteins and their interacting RING finger proteins repress gibberellin responses by binding to the promoters of a subset of gibberellin‐responsive genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 927–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson AH, Wendel JF, Gundlach H, Guo H, Jenkins J, Jin DC, Llewellyn D, Showmaker KC, Shu SQ, Udall J et al 2012. Repeated polyploidization of Gossypium genomes and the evolution of spinnable cotton fibers. Nature 492: 423–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patikoglou GA, Kim JL, Sun L, Yang SH, Kodadek T, Burley SK. 1999. TATA element recognition by the TATA box‐binding protein has been conserved throughout evolution. Genes & Development 13: 3217–3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renny‐Byfield S, Page JT, Udall JA, Sanders WS, Peterson DG, Arick MA, Grover CE, Wendel JF. 2016. Independent domestication of two Old World cotton species. Genome Biology and Evolution 8: 1940–1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renny‐Byfield S, Wendel JF. 2014. Doubling down on genomes: polyploidy and crop plants. American Journal of Botany 101: 1711–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rick CM, Fobes JF, Holle M. 1977. Genetic variation in Lycopersicon pimpinellifolium: evidence of evolutionary change in mating systems. Plant Systematics and Evolution 127: 139–170. [Google Scholar]

- Rombola‐Caldentey B, Rueda‐Romero P, Iglesias‐Fernandez R, Carbonero P, Onate‐Sanchez L. 2014. Arabidopsis DELLA and two HD‐ZIP transcription factors regulate GA signaling in the epidermis through the L1 box cis‐element. Plant Cell 26: 2905–2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon A, Flagel L, Ying B, Udall JA, Wendel JF. 2010. Homoeologous nonreciprocal recombination in polyploid cotton. New Phytologist 186: 123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaart JG, Mehli L, Schouten HJ. 2005. Quantification of allele‐specific expression of a gene encoding strawberry polygalacturonase‐inhibiting protein (PGIP) using Pyrosequencing™. Plant Journal 41: 493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlereth A, Moller B, Liu WL, Kientz M, Flipse J, Rademacher EH, Schmid M, Jurgens G, Weijers D. 2010. MONOPTEROS controls embryonic root initiation by regulating a mobile transcription factor. Nature 464: 913–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan C‐M, Shangguan X‐X, Zhao B, Zhang X‐F, L‐m Chao, Yang C‐Q, Wang L‐J, Zhu H‐Y, Zeng Y‐D, Guo W‐Z et al 2014. Control of cotton fiber elongation by a homeodomain transcription factor GhHOX3. Nature Communications 5: 5519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shangguan XX, Xu B, Yu ZX, Wang LJ, Chen XY. 2008. Promoter of a cotton fiber MYB gene functional in trichomes of Arabidopsis and glandular trichomes of tobacco. Journal of Experimental Botany 59: 3533–3542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small RL, Ryburn JA, Cronn RC, Seelanan T, Wendel JF. 1998. Tortoise and the hare: choosing between noncoding plastome and nuclear ADH sequences for phylogeny reconstruction in a recently diverged plant group. American Journal of Botany 85: 1301–1315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis DE, Visger CJ, Soltis PS. 2014. The polyploidy revolution then… and now: Stebbins revisited. American Journal of Botany 101: 1057–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CN, Via LE. 1993. A rapid CTAB DNA isolation technique useful for rapid fingerprinting and other PCR applications. BioTechniques 14: 748–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DB, Lloyd AM, Marks MD. 2000. Progress in the molecular genetic analysis of trichome initiation and morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Trends in Plant Science 5: 214–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Walford SA, Dennis ES, Llewellyn D. 2016. Trichomes control flower bud shape by linking together young petals. Nature Plants 2: 16 093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirosh I, Weinberger A, Carmi M, Barkai N. 2006. A genetic signature of interspecies variations in gene expression. Nature Genetics 38: 830–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walford S‐A, Wu Y, Llewellyn DJ, Dennis ES. 2011. GhMYB25‐like: a key factor in early cotton fiber development. Plant Journal 65: 785–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Q, Guan X, Yang N, Wu H, Pan M, Liu B, Fang L, Yang S, Hu Y, Ye W et al 2016. Small interfering RNAs from bidirectional transcripts of GhMML3_A12 regulate cotton fiber development. New Phytologist 210: 1298–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Elbein SC. 2007. Detection of allelic imbalance in gene expression using Pyrosequencing® In: Walker JM, Marsh S, eds. Pyrosequencing® protocols. Totowa, NJ, USA: Humana Press, 157–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Zhu Y, Fujioka S, Asami T, Li J, Li J. 2009. Regulation of Arabidopsis brassinosteroid signaling by atypical basic helix‐loop‐helix proteins. Plant Cell 21: 3781–3791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KB, Wang ZW, Li FG, Ye WW, Wang JY, Song GL, Yue Z, Cong L, Shang HH, Zhu SL et al 2012. The draft genome of a diploid cotton Gossypium raimondii . Nature Genetics 44: 1098–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Tu L, Lin M, Lin Z, Wang P, Yang Q, Ye Z, Shen C, Li J, Zhang L et al 2017. Asymmetric subgenome selection and cis‐regulatory divergence during cotton domestication. Nature Genetics 49: 579–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Wang JW, Yu N, Li CH, Luo B, Gou JY, Wang LJ, Chen XY. 2004. Control of plant trichome development by a cotton fiber MYB gene. Plant Cell 16: 2323–2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XY, Paterson AH. 2011. Gene conversion in angiosperm genomes with an emphasis on genes duplicated by polyploidization. Genes 2: 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel JF. 1989. New World tetraploid cottons contain Old World cytoplasm. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 86: 4132–4136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel JF. 2015. The wondrous cycles of polyploidy in plants. American Journal of Botany 102: 1753–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel JF, Brubaker C, Alvarez I, Cronn R, Stewart JM. 2009. Evolution and natural history of the cotton genus In: Paterson AH, ed. Genetics and genomics of cotton. New York, NY, USA: Springer, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wendel JF, Brubaker CL, Seelanan T. 2010. The origin and evolution of Gossypium In: Stewart JM, Oosterhuis DM, Heitholt JJ, Mauney JR, eds. Physiology of cotton. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wendel JF, Cronn RC. 2003. Polyploidy and the evolutionary history of cotton. Advances in Agronomy 78: 139–186. [Google Scholar]

- Wendel JF, Grover CE. 2015. Taxonomy and evolution of the cotton genus, Gossypium In: Fang DD, Percy RG, eds. Cotton. Madison, WI, USA: American Society of Agronomy Inc., Crop Science Society of America Inc., and Soil Science Society of America Inc., 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wittkopp PJ, Kalay G. 2012. Cis‐regulatory elements: molecular mechanisms and evolutionary processes underlying divergence. Nature Reviews Genetics 13: 59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray GA. 2007. The evolutionary significance of cis‐regulatory mutations. Nature Reviews Genetics 8: 206–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Tian Y, Wan Q, Fang L, Guan X, Chen J, Hu Y, Ye W, Zhang H, Guo W et al 2018. Genetics and evolution of MIXTA genes regulating cotton lint fiber development. New Phytologist 217: 883–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, Gou JY, Li FG, Shangguan XX, Zhao B, Yang CQ, Wang LJ, Yuan S, Liu CJ, Chen XY. 2013. A cotton BURP domain protein interacts with alpha‐expansin and their co‐expression promotes plant growth and fruit production. Molecular Plant 6: 945–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo MJ, Szadkowski E, Wendel JF. 2013. Homoeolog expression bias and expression level dominance in allopolyploid cotton. Heredity 110: 171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo MJ, Wendel JF. 2014. Comparative evolutionary and developmental dynamics of the cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) fiber transcriptome. PLoS Genetics 10: e1004073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LY, Bai MY, Wu J, Zhu JY, Wang H, Zhang Z, Wang W, Sun Y, Zhao J, Sun X et al 2009. Antagonistic HLH/bHLH transcription factors mediate brassinosteroid regulation of cell elongation and plant development in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21: 3767–3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Hu Y, Jiang W, Fang L, Guan X, Chen J, Zhang J, Saski CA, Scheffler BE, Stelly DM et al 2015. Sequencing of allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L. acc. TM‐1) provides a resource for fiber improvement. Nature Biotechnology 33: 531–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Lv Y, Wang Y, Rose JK, Shen F, Han Z, Zhang X, Xu X, Wu T, Han Z. 2016. TATA box insertion provide a selected mechanism for enhancing gene expression to adapt Fe deficiency. Plant Physiology 173: 715–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhiponova MK, Morohashi K, Vanhoutte I, Machemer‐Noonan K, Revalska M, Van Montagu M, Grotewold E, Russinova E. 2014. Helix‐loop‐helix/basic helix‐loop‐helix transcription factor network represses cell elongation in Arabidopsis through an apparent incoherent feed‐forward loop. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 111: 2824–2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: Wiley Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any Supporting Information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the New Phytologist Central Office.

Fig. S1 Pyrosequencing of homoeologous PRE1 transcripts of allotetraploid cottons.

Fig. S2 TATA‐box mediates PRE1 promoter activity in cotton fiber cells.

Fig. S3 GhPRE1A promotes cell elongation in Arabidopsis.

Fig. S4 GhPRE1 is expressed in fibers during the fast elongation period in fiber‐producing cotton species.

Fig. S5 View of fibers (seed trichomes) of five allotetraploid cotton species.

Fig. S6 The PRE1 locus in the genomes of four cotton species.

Table S3 The PRE1 loci in reported cotton species

Table S1 Diploid and allotetraploid cottons surveyed in this investigation

Table S2 Primers used in this investigation

Table S4 Distribution of the TATA‐box indel in cotton accessions