Abstract

Most tissue-engineered arterial grafts are complicated by aneurysmal dilation secondary to insufficient neotissue formation after scaffold degradation. The optimal graft would form an organized multilayered structure with a robust extracellular matrix that could withstand arterial pressure. The purpose of the current study was to determine how oversizing a biodegradable arterial scaffold affects long-term neotissue formation. Size-matched (1.0 mm, n = 11) and oversized (1.6 mm, n = 9) electrospun polycaprolactone/chitosan scaffolds were implanted as abdominal aortic interposition grafts in Lewis rats. The mean lumen diameter of the 1.6 mm grafts was initially greater compared with the native vessel, but matched the native aorta by 6 months. In contrast, the 1.0 mm grafts experienced stenosis at 6 and 9 months. Total neotissue area and calponin-positive neotissue area were significantly greater in the 1.6 mm grafts by 6 months and similar to the native aorta. Late-term biomechanical testing was dominated by remaining polymer, but graft oversizing did not adversely affect the biomechanics of the adjacent vessel. Oversizing tissue-engineered arterial grafts may represent a strategy to increase the formation of organized neotissue without thrombosis or adverse remodeling of the adjacent native vessel by harnessing a previously undescribed process of adaptive vascular remodeling.

Keywords: : tissue-engineered arterial graft, size mismatch, polycaprolactone, chitosan, electrospinning, rat model

Introduction

Coronary artery disease is the leading cause of death worldwide, and peripheral vascular disease threatens both life and limb.1–4 Autologous tissue is the gold standard for surgical bypass in both fields, but even the use of native vessels can be complicated by graft failure. Furthermore, such vessels are not available in some patients due to concomitant peripheral vascular disease or the need for a large diameter conduit.5–7 Synthetic grafts are fraught with an even greater risk of postoperative complications, such as pseudoaneurysm, calcification, infection, and thrombosis, which often require emergent reoperation.8–12 In recent decades, intensive research has explored the potential of a tissue-engineered alternative for small-caliber arterial replacement, which would offer an autologous off-the-shelf vascular graft with the ability to grow, remodel, and self-repair, resembling a native artery in both form and function.13,14

Tissue engineering is a multidisciplinary field combining biomedical engineering, material science, regenerative medicine, and immunology.15 It leverages the body's innate regenerative capacity to provide an alternative source of autologous tissue, with host cells replacing implanted biodegradable scaffolds over time.16,17 However, many existing tissue-engineered vascular grafts (TEVGs) have been unable to withstand arterial pressures in long term and develop aneurysms.18,19 The ideal arterial TEVG would develop a more organized multilayered structure and have more robust extracellular matrix designed to resist aneurysmal dilation. Myriad parameters are considered when designing arterial TEVG scaffolds, including but not limited to: polymer type, degradation rate, mechanical properties, pore size, fiber diameter, fiber alignment, and wall thickness.18,20,21 Interestingly, little is known regarding the effects of TEVG scaffold lumen diameter relative to the native artery into which it is interposed.22–24 Most often, size matching is considered a requisite design criterion for (bio)synthetic small-diameter arterial grafts. The current study aims to question this assumption, perhaps providing insight on potential strategies to improve the performance of arterial TEVGs. In this study, we sought to determine if oversizing bioresorbable tissue-engineered arterial grafts relative to the adjacent artery affects neointimal formation in a rat abdominal aortic interposition model. Such findings have the potential to inform the design of arterial TEVGs by permitting fine-tuning of wall thickness and luminal diameter and, consequent, mechanical properties, thus supporting viable neoartery formation without dilation, thrombosis, or stenosis.

Materials and Methods

Graft fabrication

Polycaprolactone (PCL) (Mn 70,000–90,000) and chitosan (CS) (Medium molecular weight) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Co, LLC (MO). Hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) and acetic acid (AA) (99.7%) were purchased from Oakwood Chemicals and Sigma Aldrich, respectively. All polymers and solvents were used without further modification. CS was dissolved in a 9:1 w/w solution of HFIP and AA to produce a 0.15 wt% CS solution that was stirred using a magnetic stir bar for 3 h at 50°C. PCL was then added to the CS solution in a 20:1 w/w ratio of PCL and CS and stirred using a magnetic stir bar for 21 h at 50°C. The PCL/CS solution was placed in a 20 cc Luer-Lok syringe and dispensed at a flow rate of 5 mL/h through a 20-gauge blunt needle tip. Mandrels of 1.0 mm and 1.6 mm diameter were used for the grafts. The mandrel was positioned 20 cm from the needle tip and was rotated at 100 rpm. A +25 kV charge was applied to the needle tip, and a −4 kV charge was applied to the mandrel. The electrospun nanofibers were deposited to create a 100 ± 10 μm wall thickness tube for the grafts. The PCL/CS tubes were then cut into scaffolds, each of which was 3 mm in length. Finally, all the PCL/CS scaffolds were terminally sterilized with 35 kGy of gamma irradiation.

Scanning electron microscope

Ring samples of the 1.0 and 1.6 mm PCL-CS scaffolds were mounted on carbon tape and gold sputter coated under vacuum (3 nm thickness). Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images were obtained using a Hitachi S-4800 SEM at 40 × magnification (5 kv, 10,000 mA).

Graft implantation

Twelve-week-old female Lewis rats (n = 20) received either a 1.0 mm (n = 11) or a 1.6 mm (n = 9) PCL-CS scaffold (Fig. 1B) as an infrarenal aortic interposition graft. A 1.0 mm inner diameter was deemed “size matched” based on intraoperative measurements acquired during pilot studies before this investigation. Likewise, a 1.6 mm inner diameter was selected as the largest feasible conduit able to be safely implanted in the rat model. Briefly, rats were induced with isoflurane (3–5% in 100% O2) and administered an anesthetic cocktail of ketamine (10 mg/kg) and xylazine (100 mg/kg). The abdomen was shaved, prepped, and draped in sterile manner. A midline incision was made and a self-retaining retractor placed. The intestines were eviscerated and wrapped in sterile saline-soaked gauze. The retroperitoneum was exposed and peritoneal attachments to the descending colon incised. Blunt dissection exposed and isolated the infrarenal aorta and inferior vena cava. Lumbar branches to the aorta were ligated with suture. Vascular control was obtained with microvascular clips, and the abdominal aorta divided between the proximal renal branches and the distal iliac bifurcation. Scaffolds were implanted as interposition grafts using running 9-0 PROLENE suture (Fig. 1C). Upon completion of the anastomoses, vascular clips were released and hemostasis ensured. The intestines were returned to the abdominal cavity, which was closed in two layers with running 6-0 PROLENE suture. Animals were recovered without the use of antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs and survived until the 6- or 12-month study end points.

FIG. 1.

(A) Schematic overview of study design: TEVG scaffolds were implanted and followed with serial ultrasound imaging at 1, 3, 6, and 9 months postoperatively. Samples were harvested at 6 months for histologic analyses and at 12 months for μCT-angiography, biaxial mechanical testing, and histology. (B) Representative scanning electron microscope images of 1.0 mm (left) and 1.6 mm (right) TEVG scaffolds before implantation at equivalent magnification (40 × ). (C) Intraoperative photographs of TEVG explantation demonstrating the size-matched 1.0 mm (left) and size mismatched 1.6 mm (right) grafts. Adventitial sutures are placed at explant to allow determination of in vivo axial stretch for biaxial mechanical testing. Scale bar = 1.0 mm. μCT, microcomputed tomography; TEVG, tissue-engineered vascular graft. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Ultrasound monitoring

At 3, 6, 9, and 12 months postimplantation, grafts were evaluated with transabdominal high frequency ultrasonography (Vevo 2100; VisualSonics, Inc., Toronto, Canada). Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (3–5% vaporized in 100% O2 at 1 L/min), and body temperature was maintained at 38°C. The abdomen was chemically depilated and ultrasound gel applied. Ultrasound images were captured in B-mode, M-mode, and pulse wave/color Doppler. The lumen diameters of the TEVG or native aorta were measured with ImageJ (NIH) and calculated as an average of three different measurements along the length of the vessel in the region of interest (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea).

Tissue harvest

At the study end point, animals were euthanized by intraperitoneal administration of an overdose cocktail of ketamine (300 mg/kg) and xylazine (30 mg/kg). Animals were systemically perfused with normal saline through the left ventricle. Grafts intended for histologic analysis were perfusion-fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) and explanted. Grafts and proximal abdominal aortas intended for biaxial mechanical testing were marked with 10-0 PROLENE suture along their length, allowing for calculation of the in vivo axial stretch (Fig. 1C), explanted, and stored in 1 × Hank's buffered saline at 4°C. After mechanical testing, specimens were fixed in 10% NBF as above.

Micro-contrast enhanced angiography and image reconstruction

After euthanasia, two animals from each group at the 12-month time point were prepared for contrast-enhanced microcomputed tomography (μCT) angiography by systemic perfusion with normal saline through the thoracic aorta. A 6.0 mL bolus of contrast (Omnipaque, 300 mg/mL) was administered through a PE-10 catheter. Whole-body μCT was performed with the GE eXplore Locus (GE Healthcare) at a spatial resolution of 45 μm. Imaging parameters included the following: number of views (720), angle of increment (0.5), tube potential (80 kVp), tube current (450 mA), single view exposure time (2000 ms), scan method (360), Bin mode (1), camera gain (0), and frames.5 The reconstructed slices were output in the CT manufacturer's raw format (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine [DICOM]), and the reconstructed images were viewed and analyzed using the Vitrea Enterprise Suite Software 6.7.0 (Vital; A Toshiba Medical Systems Company). The DICOM images were initially reconstructed into axial, coronal, and sagittal planes to identify the aorta and graft for three-dimensional reconstruction. After identification of the graft, cross-sectional measurements at the mid-graft, superior, and inferior margin were obtained using two orthogonal planes to obtain a true cross section. Cross-sectional measurements for the proximal and distal infrarenal abdominal aorta were obtained in a similar manner 0.5 mm adjacent to the graft, as well as at 0.5 mm increments below and above the graft for a total of 2 mm (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Biaxial mechanical testing

Composite vessels (proximal infrarenal abdominal aorta, graft, and distal infrarenal abdominal aorta) were cannulated and secured to custom drawn, size-matched micropipettes with 6-0 suture and a small drop of cyanoacrylate. The adjacent proximal and distal aorta aided with the requisite cannulation of each specimen and allowed assessment of possible graft-induced changes to the host aorta. The cannulated vessels were placed in a custom computer-controlled micromechanical biaxial testing device within a Hank's Buffered Salt Solution,25 and initial dimensions (outer diameter and axial length) were recorded in the unloaded state. Before testing, vessels were equilibrated at 80 mmHg with physiological intraluminal flow for 15 min at their estimated in vivo axial stretch and, subsequently, preconditioned at this axial stretch using four cycles of pressurization from 10 to 140 mmHg.26 Following preconditioning, unloaded dimensions were measured again, and the in vivo axial stretch of the composite vessel was defined in vitro by identifying the axial stretch at which the measured axial force remained nearly constant in response to changes in intraluminal pressure. With the camera focused on the central region of the graft, each specimen was subjected to two cycles of pressure-diameter testing consisting of cyclic pressurization from 10 to 140 mmHg at the experimentally determined in vivo axial stretch ratio (and at ±5% of this value). Pressure-diameter testing was then repeated with the camera focused on the proximal infrarenal abdominal aorta. Intraluminal pressure, axial force, outer diameter, and overall axial length were measured continually throughout mechanical testing. Circumferential Cauchy stress and stretch were calculated as described previously.26

Histology, immunohistochemistry, and image analysis

Formalin-fixed specimens were transferred to 70% EtOH after 24 h at 4°C. Samples were embedded in paraffin and serially sectioned (4 μm sections). Slides were stained for hematoxylin and eosin, Masson's trichrome, and Picrosirius red following standard techniques. CD-68+ macrophages and calponin+ contractile smooth muscle cells were identified by immunohistochemistry. Briefly, slides were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated with a graded EtOH series. Antigens were retrieved in citrate buffer (pH 6.0; Dako), followed by blocking of endogenous peroxidase activity and nonspecific antibody binding (3% H2O2 and Background Sniper; Biocare Medical, respectively). Slides were then incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4°C: mouse anti-CD-68 (1:500, ab31630; Abcam) and rabbit anti-calponin (1:500, ab46794; Abcam). Antibody binding was detected by incubation with a species-specific biotinylated secondary antibody (1:500; Vector Labs) followed by streptavidinated horseradish peroxidase (Vector Labs) and chromogenic detection with 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine. Nuclei were counterstained with Gill's hematoxylin (Vector Labs), and slides were dehydrated and permanently mounted. Sections of native rat aorta were utilized as positive controls for all histologic and immunohistochemical stains (Supplementary Fig. S3). Photomicrographs were captured at 5× and 20× magnifications with a Zeiss Axio Observer.Z1 inverted microscope and a Zeiss AxioCam 105 digital camera. Image analysis was performed using ImageJ as previously described.19 Polarized light was used to image Picrosirius red staining, and collagen fiber thickness and remaining scaffold polymer were quantified from four random 20× dark-field images. CD-68+ cells were manually counted from four random 20× fields per sample.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean unless otherwise indicated. Lumen diameter measurements derived from ultrasound and histologic images or μCT reconstructions were compared using ordinary two-way analysis of variance followed by Sidak's multiple comparison test. Calponin+ area fractions, the number of CD-68+ cells/mm2, collagen area, collagen fiber thicknesses, and remaining scaffold polymer area fraction were also compared in this manner. The alpha was controlled at 0.05, and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Survival proportions were compared using Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) was used for all statistical hypothesis testing.

Results

Gross outcomes

Perioperative mortality was 0%. One rat receiving a 1.0 mm graft died before the 6-month end point due to circumstances unrelated to the study. Three rats in the 1.6 mm group died either 35 (n = 2) or 46 (n = 1) days before the 12-month end point (Supplementary Fig. S4). A veterinarian performed complete necropsies and determined that the deaths were due to natural causes unrelated to TEVG implantation. These late-term specimens were thus included in the 12-month time point group. Gross examination revealed that the 1.6 mm grafts were widely patent at both 6 and 12 months, with no evidence of aneurysmal dilation. All 1.0 mm grafts were patent at 6 months with no dilation noted, but 20% (one of five) of these 1.0 mm grafts were occluded in the 12-month cohort. This occluded specimen was excluded from histomorphometric analyses.

Graft lumen diameter over time is related to degree of TEVG size matching at implantation

Longitudinal ultrasound analysis revealed that the 1.0 mm grafts experienced inward remodeling over the first 9 months—with lumen diameters 66 ± 11% and 67 ± 7% that of the native aorta at 6 and 9 months postimplantation, respectively—followed by slight increases in lumen from 9 to 12 months (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the lumen diameters of the 1.6 mm grafts remained significantly greater compared with the native aorta up to 3 months postimplantation, after which intimal neotissue formation resulted in a size-matched lumen diameter, with no significant difference between TEVG and native aortic lumen diameters at 6, 9, and 12 months postimplantation (Fig. 2C). Overall, these data revealed a significantly greater diameter in the 1.6 mm group at 1, 3, 6, and 9 months postimplantation (Fig. 2A) with no significant difference between the 1.0 mm and 1.6 mm groups at 12 months. Late-term μCT angiography confirmed the ultrasonographic findings at 12 months. Indeed, lumen diameters appeared comparable between the 1.0 and 1.6 mm groups at the levels of the proximal aorta, proximal anastomosis, mid-graft, distal anastomosis, and distal aorta, although statistical hypothesis testing was not warranted due to small sample size (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 2.

(A) Transabdominal ultrasonographic assessment of TEVG lumen diameters over time. TEVGs of 1.6 mm cohort had significantly larger lumen diameters than the 1.0 mm cohort at 1, 3, 6, and 9 months postimplantation. Lumen diameters in each group were equivalent at 12 months. (B) Direct comparison of the 1.0 mm TEVG lumen diameters compared to the adjacent abdominal aorta revealed significant graft narrowing at 6 and 9 months. (C) The same comparison of lumen diameters in the 1.6 mm cohort indicated no significant difference between the TEVG and native vessel after 3 months. ****p < 0.0001, **p < 0.005.

FIG. 3.

Representative three-dimensional μCT-angiography reconstructions of (A) 1.0 mm and (B) 1.6 mm (n = 2/group) TEVGs at the 12-month time point. (C) Comparison of cross-sectional lumen diameter measurements derived from two orthogonal planes of the proximal aorta (0.5 mm above the anastomosis), proximal anastomosis, mid-TEVG, distal anastomosis, and distal aorta (0.5 mm below the anastomosis) indicated that late-term lumen diameters were similar regardless of graft lumen diameter at implantation. Raw μCT images and measurements are provided in Supplementary Figure S2 for clarity. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Graft lumen dimensions at implantation do not affect late-term mechanical behavior

The outer diameter of the 1.0 mm grafts matched that of the proximal infrarenal abdominal aorta at physiologic pressures; conversely, the outer diameter of the 1.6 mm grafts was significantly greater compared with the adjacent proximal aorta under the same conditions despite both grafts having nearly identical luminal diameters at 12 months (Fig. 2A). Both the 1.0 and the 1.6 mm grafts exhibited high circumferential structural stiffness at physiologic pressures 12 months postimplantation (Fig. 4A). Indeed, the full pressure-diameter curves revealed little compliance in these grafts over a pressure range of 10–140 mmHg compared with the proximal infrarenal abdominal aorta. This high structural stiffness is likely due to the slow degradation of the PCL-CS scaffold; hence the mechanical behavior of these initially stiff, polymer-dominated grafts persists independent of the different initial luminal diameters or differential neotissue formation and remodeling between the two graft designs. There was also no difference in the circumferential structural stiffness of the proximal infrarenal abdominal aorta adjacent to the 1.0 and 1.6 mm grafts 12 months postimplantation (Fig. 4A). This finding suggests that the larger initial luminal diameter of the oversized grafts does not adversely affect the remodeling of adjacent aorta due to graft implantation. Circumferential Cauchy stress–stretch data similarly show minimal differences in material stiffness between the 1.0 and 1.6 mm grafts; both have significantly higher material stiffness than the adjacent proximal aorta, again reflecting the presence of residual polymer even after 12 months (Fig. 4B). The material stiffness of the proximal aorta does not differ between the 1.0 and 1.6 mm cohorts, suggesting that although the proximal aorta may have remodeled to compensate for the high stiffness of the interposition graft,19 this remodeling response does not depend on initial graft luminal diameter (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

(A) Pressure-diameter responses of 1.0 mm (n = 4) and 1.6 mm (n = 4) luminal diameter grafts and the adjacent PIAA 12 months postimplantation. Data are plotted as the last cycle of unloading at the in vivo axial stretch following preconditioning. Note the significantly higher circumferential structural stiffness of the grafts compared to the adjacent aorta and the mismatch between the outer diameter of the 1.6 mm grafts and the proximal aorta despite matching luminal diameters. There was no difference in the circumferential structural stiffness of the PIAA adjacent to 1.0 and 1.6 mm grafts 12 months postimplantation, suggesting that graft luminal diameter at implantation does not adversely affect remodeling of the adjacent aorta. (B) Circumferential Cauchy stress–stretch data for 1.0 mm (n = 4) and 1.6 mm (n = 4) luminal diameter grafts and the adjacent PIAA 12 months postimplantation. Data are plotted as the last cycle of unloading at the in vivo axial stretch following preconditioning. The grafts have significantly higher material stiffness compared with the adjacent proximal aorta, likely secondary to residual polymer present even after 12 months (Supplementary Fig. S4). The material stiffness of the proximal aorta does not differ between the 1.0 and 1.6 mm cohorts, suggesting that its remodeling is independent of initial graft luminal diameter. PIAA, proximal infrarenal abdominal aorta.

Scaffold size mismatch encourages favorable neotissue composition and organization

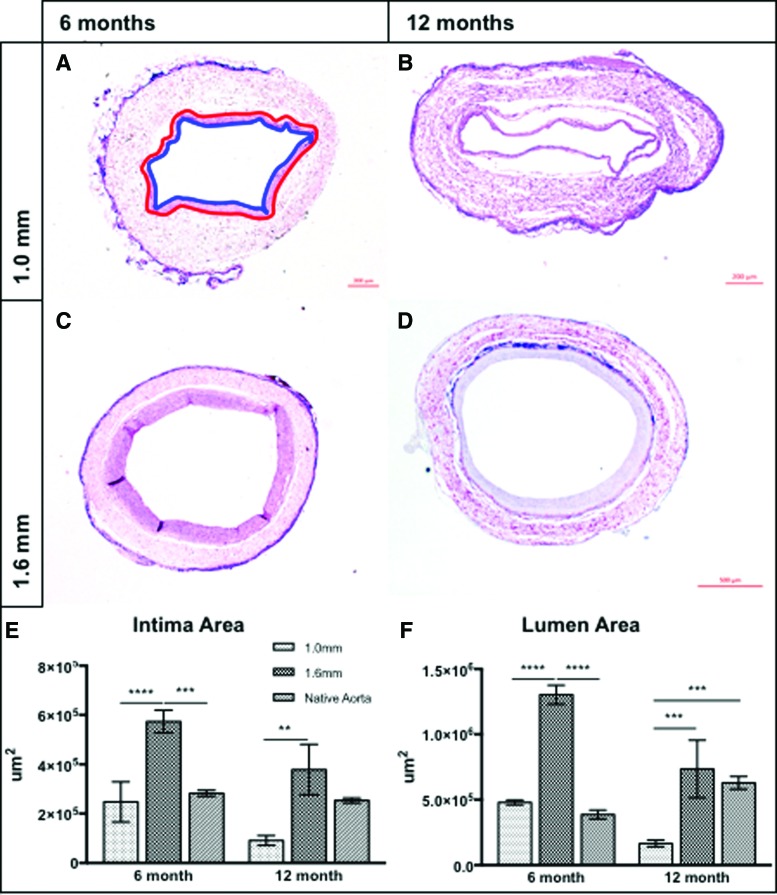

At 6 and 12 months postimplantation, the 1.6 mm TEVGs had a significantly greater intimal neotissue area than their 1.0 mm counterparts. At 6 months, the intimal area of the 1.6 mm TEVGs was also greater than the native aorta; at 12 months, however, this difference resolved and the intimal area of the 1.6 mm graft was statistically equivalent to that of the native aorta (Fig. 5E). Similarly, the 1.6 mm group had a significantly larger mean lumen area compared with the 1.0 mm group and the native aorta at 6 months. Interestingly, at 12 months, the lumen areas of the native aorta and 1.6 mm TEVGs were equivalent, whereas the lumen area of the 1.0 mm TEVGs was significantly less than both the 1.6 mm group and the native aorta (Fig. 5F), confirming in vivo ultrasound results.

FIG. 5.

Representative hematoxylin and eosin photomicrographs of 1.0 mm (A, B) and 1.6 mm (C, D) TEVGs at 6 (A, C) and 12 (B, D) months postimplantation. Red tracing of the scaffold/neointimal margin and blue tracing of the neointimal/luminal margin in (A) contains the intimal tissue areas quantified and compared in (E). Grafts of 1.6 mm contained significantly more luminal neotissue than 1.0 mm grafts and the native aorta at 6 months. At 12 months, the 1.6 mm intimal area was >1.0 mm grafts, but equivalent to the native aorta. Quantification of lumen area (F) demonstrated similar trends: 1.6 mm grafts were characterized by significantly larger lumens than both 1.0 mm grafts and the native aorta at 6 months, but at 12 months, lumen areas of both the native aorta and 1.6 mm grafts were larger than the 1.0 mm group. No difference between 1.6 mm grafts and the native aorta was observed at 12 months. ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.0005, **p < 0.005. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Immunohistochemistry identifying calponin demonstrated a significant difference in the amount of mature contractile smooth muscle cells constituting the intimal neotissue between the two groups at 6 months, with 1.6 mm grafts having more intimal calponin staining (Fig. 6I). Both the 1.6 and 1.0 mm grafts contained significantly fewer calponin+ cells than the native aorta. The difference between the 1.6 and 1.0 mm groups, while trending in the same direction, was not significant at 12 months, and both groups had significantly less calponin staining than the native vessel. No difference in CD-68+ cell density (number/mm2) was identified between groups at 6 or 12 months. Yet, the inflammation at 12 months was appreciably greater than at 6 months in the 1.0 mm group (Fig. 6J). Late-term inflammation may be associated with residual polymer, which remained up to 12 months after implantation in both cohorts (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. S5).

FIG. 6.

Representative immunohistochemical staining for calponin (A–D) and CD-68 (F–I) for 1.0 mm (A, B, F, G) and 1.6 mm (C, D, H, I) grafts at the 6 (A, C, F, H) and 12 (B, D, G, I) month time points. “l” denotes the graft lumen, and “*” indicates suture material. (E) Quantification of calponin+ intimal area suggests that both constructs contained less contractile vascular smooth muscle cells than the native artery at both time points. At 6 months, the 1.6 mm grafts contained significantly more calponin+ intimal neotissue than the 1.0 mm grafts. (J) Quantification of CD-68+ cell numbers between groups at both time points indicated the persistence of chronic inflammation that did not depend on graft dimensions at implantation. ****p < 0.0001, **p < 0.005, *p < 0.05. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Characterization of extracellular matrix composition was prompted by the differential neotissue formation observed between 1.0 and 1.6 mm grafts (Fig. 7). Total collagen content was quantified using Masson's trichrome staining (images not shown), and no significant differences between groups and the native aorta at either time were observed (Fig. 7E). Visualization of Picrosirius red imaging with polarized light allowed quantification of collagen fiber size and fibrillar collagen packing, with red fibers being thicker than green fibers and orange/yellow fibers being of an intermediate thickness. Both implant groups were characterized by significantly less thick collagen fibers than the native aorta at 6 months (Fig. 7F). No other significant differences were discovered at this time point. After 12 months, the majority of the collagen fibers were thick in both groups; both size-matched and oversized graft sections contained significantly more red fibers than the native aorta (Fig. 7G). No differences between thin and intermediate fibers were observed.

FIG. 7.

Representative Picrosirius red imaging visualized under polarized light for 1.0 mm (A, C) and 1.6 mm (B, D) grafts at the 6 (A, B) and 12 (C, D) month time points. “l” denotes the graft lumen. (E) Comparison of total collagen content between TEVG cohorts and the native aorta. No significant difference at either time point was observed. (F) Comparison of collagen fiber thickness derived from color thresholding of dark-field images at the 6-month time point indicated that the 1.0 and 1.6 mm grafts contained less mature thick fibers (red) than the native aorta. Distribution of intermediate and thin fibers was similar between groups. (G) Collagen composition analysis at 12 months revealed an inversion of trends observed at 6 months; both the 1.0 and 1.6 mm grafts were composed of significantly more mature thick fibers than the native aorta, likely secondary to the chronic inflammatory response elicited by the residual polymer. No differences between intermediate and thin fibers were observed. ****p < 0.0001. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Discussion

Relatively little is known regarding the effects of size mismatching on the performance of small diameter tissue-engineered arterial grafts in vivo. No prior studies have examined size mismatching of biodegradable arterial grafts as a means to modulate neotissue formation. In this prospective small animal study, we longitudinally evaluated arterial neotissue formation and remodeling using a previously designed biodegradable nanofiber scaffold27 implanted in a rat abdominal aortic interposition model. Our findings suggest that oversizing biosynthetic conduits relative to the native artery may provide a strategy to increase organized vascular neotissue formation without adversely affecting the biomechanics of the adjacent vessel. In addition, the augmented intimal tissue formation did not incur any adverse events such as stenosis or thrombosis. We observed that in this rat model, neoarterial tissue develops on the luminal surface of oversized PCL-CS scaffolds such that the graft luminal area matches that of the adjacent artery over the course of 1 year through a mechanism of adaptive vascular remodeling. The homeostatic compensatory phenomenon characterized in this report may be a valuable parameter in the rational optimization of small diameter tissue-engineered arterial grafts for clinical use.

The traditional approach to vascular interposition grafting favors isodiametric (size-matched) grafts.28–30 Interruption of laminar flow and reduction in local wall shear stress have been implicated in the use of oversized grafts,22,31 creating a risk for poor endothelialization, the development of thrombus with excessive fibrin deposition, and the progression of neointimal hyperplasia.23,28,32 Yet oversized vascular grafts are common in surgical reconstruction of complex congenital cardiac anomalies, allowing young children to “grow into” their graft, thus reducing the likelihood of reoperation for somatic overgrowth.33 The implications of this technique in the context of vascular tissue engineering are understudied, yet clinical practice suggests that in cases of nonisodiametric grafting, vascular remodeling persists until laminar flow is restored, often resulting in thick-walled grafts relative to the native vessel. The majority of these instances occur in low-pressure high-flow environments (e.g., the extracardiac total cavopulmonary connection), but a similar degree of vascular tissue formation may accompany graft oversizing in the arterial circulation.

A principal challenge in the field of tissue-engineered arterial grafts is the high incidence of aneurysmal dilation, often leading to catastrophic rupture.18 This complication results most frequently from insufficient structural stiffness of the neoartery during the course of graft degradation. Indeed, only one study has reported successful neoartery formation after near complete polymer degradation in vivo.34 Concerns of catastrophic rupture prompt utilization of slow-degrading scaffold materials to allow sufficient time for extracellular matrix deposition and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. However, slow-degrading scaffolds stimulate chronic inflammation, which has been implicated in ectopic calcification, excessive collagen deposition, and disorganized vascular neotissue.18,35 To date, the successful tuning of tissue-engineered arterial grafts to promote satisfactory tissue formation and complete scaffold degradation in vivo has been elusive.19 Many parameters are considered in the design of arterial scaffolds to achieve this goal, including but not limited to the following: wall thickness, pore size, porosity, fiber diameter, fiber alignment, fiber degradation rate, and elasticity.20,21 The present findings suggest that lumen diameter may be an additional important parameter.

We found that oversizing arterial scaffolds relative to the native artery promote increased intimal neotissue formation and extracellular matrix deposition without an increase in macrophage infiltration over the course of 1 year compared to size-matched TEVGs. While the precise mechanisms underlying this enhanced tissue formation is outside the scope of the current investigation, we suggest that remodeling neoarterial tissue may compensate for local disturbances in laminar flow and wall shear stress that result from the use of an oversized graft. This phenomenon may provide an alternative strategy to increase the structural stiffness of the implanted construct to a point where the TEVG could withstand physiologic arterial pressures without dilation or rupture after polymer degradation. Biaxial mechanical testing of the adjacent artery further indicates that this technique would not adversely affect the native vessel surrounding the implant. Histologically, the oversized conduit provided a biomimetic intimal thickness and lumen area after 1 year. In contrast, the size-matched graft demonstrated favorable tissue formation at 6 months, but subsequent remodeling resulted in a smaller lumen area at 1 year compared to the native aorta. The calponin content of the neointimal tissue in the oversized graft approached, but failed to match, that of the native artery, yet it exceeded that of the size-matched graft. We previously showed that neotissue formation is an inflammation-mediated process dominated by infiltrating monocytes and macrophages.36,37 CD-68 staining indicated that size mismatching did not alter the inflammatory response of the host to scaffold implantation, potentially implicating additional mechanisms of neotissue formation contributing to the late-term results described herein. Analysis of the extracellular matrix showed that the total amount of collagen in sections from each graft type and the native vessel was similar, but the distribution of fiber thicknesses and fibrillar collagen packing at 1 year suggests scar tissue formation and chronic inflammation, most likely secondary to the slow degradation rate of the PCL-CS scaffold. We suggest that, while observational and phenomenological, the results from this study support future evaluation of a rapidly degrading oversized scaffold. Although the present study was not designed for rigorous statistical comparisons at multiple times, the data are sufficient to initial regression studies that can inform computational models.21,38 Such models may help identify optimal scaffold parameters in a more cost- and time-efficient manner, focusing on the future experiments. In this way, we can seek to find a geometry that would permit sufficient neotissue formation such that, despite early loss of scaffold integrity, the resultant neoartery would support physiologic requirements of the arterial circulation.

Future studies will similarly need to address other present limitations. First, the biaxial mechanical assessments revealed behaviors that were dominated by the residual polymer; hence data on the biomechanical benefits of increased neotissue formation were inconclusive in the oversized grafts. Second, the wall thickness of the scaffolds was controlled at 100 ± 10 μm, which resulted in different wall thickness to lumen diameter ratios (0.10 for 1.0 mm and 0.06 for 1.6 mm scaffolds). This difference could theoretically contribute to the differences observed in neotissue formation and remodeling, as wall thickness contributes to the structural stiffness of the construct and therefore impacts effects of local mechanical stimuli on TEVG neotissue.39 It is noted, however, that both implant groups demonstrated relatively low compliance (i.e., supraphysiologic structural stiffness); hence, structural effects of differing wall thickness to lumen diameter ratios were likely negligible. Future studies evaluating more compliant and faster degrading biomaterials should include wall thickness to lumen diameter ratio as a design parameter. Third, the time course of 1 year was selected due to the use of adult rats for implantation. Future studies should utilize younger animals to allow 2-year follow-up and to ensure complete scaffold degradation in vivo. As with many preliminary in vivo studies, the statistical comparisons may have been underpowered due to a low number of animals in each group. Refinement of scaffold design and parallel studies in a mouse model would also contextualize the phenomenon in the broader scope of work done by our group. Finally, quantification of immunohistochemical stains, while important, would be best validated using molecular approaches such as Western Blot and quantitative reverse transcription PCR, which could be incorporated into future experiments.

Conclusions

Oversizing TEVGs with a reduced wall thickness to lumen diameter ratio relative to the native artery provide a viable strategy to increase intimal neotissue formation and does not adversely affect the biomechanics of the adjacent vessel. Graft size mismatch may be a valuable parameter in the design of fast-degrading tissue-engineered arterial scaffolds for clinical application.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the expertise of the Morphology Core at Nationwide Children's Hospital for assistance with tissue processing and histologic staining. The authors thank Kevin Blum for acquiring scanning electron microscope images and Jacob Zbinden for assistance in obtaining photomicrographs. The authors thank the members of the Animal Resource Core at Nationwide Children's hospital for their husbandry and veterinary services. This work was funded, in part, by the Thrasher Research Fund Early Career Award (N.H.), NIH R01 HL139796 (C.K.B. and J.D.H.), NIH R01 HL128847 (C.K.B.), NIH R01 HL128602 (J.D.H. and C.K.B.), NIH R01 HL098228 (C.K.B.), NIH MSTP TG T32GM07205 (R.K.), and a Predoctoral Fellowship from the American Heart Association and The Children's Heart Foundation (R.K.). The grafts were provided by Nanofiber Solutions, Inc. (Hilliard, OH).

Disclosure Statement

Dr. C.K.B. is on the Scientific Advisory board of Cook Medical (Bloomington, IN). Dr. C.K.B. receives research support from Gunze, Ltd. (Kyoto Japan) and Cook Regentec (Indianapolis, IN). None of the funding from these grants was used to support this research. Dr. J.J. is a cofounder of Nanofiber Solutions, Inc. (Hilliard, OH). Dr. C.K.B. and Mr. C.B. are cofounders of LYST Therapeutics, LLC (Columbus, OH). Dr. N.H. receives research support from Secant Medical (Telford, PA). Remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The top 10 causes of death. 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/ Accessed October25, 2017

- 2.Baril D.T., Patel V.I., Judelson D.R., et al. Outcomes of lower extremity bypass performed for acute limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg 58, 949, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duval S., Keo H.H., Oldenburg N.C., et al. The impact of prolonged lower limb ischemia on amputation, mortality, and functional status: the FRIENDS registry. Am Heart J 168, 577, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeager R.A., Moneta G.L., Taylor L.M., Hamre D.W., McConnell D.B., and Porter J.M. Surgical management of severe acute lower extremity ischemia. J Vasc Surg 15, 385, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Souza D.S.R., Johansson B., Bojö L., et al. Harvesting the saphenous vein with surrounding tissue for CABG provides long-term graft patency comparable to the left internal thoracic artery: results of a randomized longitudinal trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 132, 373, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabik J.F., Lytle B.W., Blackstone E.H., Houghtaling P.L., and Cosgrove D.M. Comparison of saphenous vein and internal thoracic artery graft patency by coronary system. Ann Thorac Surg 79, 544, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belkin M., Knox J., Donaldson M.C., Mannick J.A., and Whittemore A.D. Infrainguinal arterial reconstruction with nonreversed greater saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg 24, 957, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ernst C.B. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. N Engl J Med 328, 1167, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Hara P.J., Hertzer N.R., Beven E.G., and Krajewski L.P. Surgical management of infected abdominal aortic grafts: review of a 25-year experience. J Vasc Surg 3, 725, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reilly L.M., Altman H., Lusby R.J., Kersh R.A., Ehrenfeld W.K., and Stoney R.J. Late results following surgical management of vascular graft infection. J Vasc Surg 1, 36, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hallett J., Marshall D.M., Petterson T.M., et al. Graft-related complications after abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: reassurance from a 36-year population-based experience. J Vasc Surg 25, 277, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veith F.J., Gupta S.K., Ascer E., et al. Six-year prospective multicenter randomized comparison of autologous saphenous vein and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene grafts in infrainguinal arterial reconstructions. J Vasc Surg 3, 104, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cleary M.A., Geiger E., Grady C., Best C., Naito Y., and Breuer C. Vascular tissue engineering: the next generation. Trends Mol Med 18, 394, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seifu D.G., Purnama A., Mequanint K., and Mantovani D. Small-diameter vascular tissue engineering. Nat Rev Cardiol 10, 410, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langer R., and Vacanti J.P. Tissue engineering. Science 260, 920, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hibino N., Villalona G., Pietris N., et al. Tissue-engineered vascular grafts form neovessels that arise from regeneration of the adjacent blood vessel. FASEB J 25, 2731, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hibino N., McGillicuddy E., Matsumura G., et al. Late-term results of tissue-engineered vascular grafts in humans. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 139, 431, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rocco K.A., Maxfield M.W., Best C.A., Dean E.W., and Breuer C.K. In vivo applications of electrospun tissue-engineered vascular grafts: a review. Tissue Eng Part B 20, 628, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khosravi R., Best C.A., Allen R.A., et al. Long-term functional efficacy of a novel electrospun poly(glycerol sebacate)-based arterial graft in mice. Ann Biomed Eng 44, 1, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Udelsman B.V., Khosravi R., Miller K.S., et al. Characterization of evolving biomechanical properties of tissue engineered vascular grafts in the arterial circulation. J Biomech 47, 2070, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller K.S., Khosravi R., Breuer C.K., and Humphrey J.D. A hypothesis-driven parametric study of effects of polymeric scaffold properties on tissue engineered neovessel formation. Acta Biomater 11, 283, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Binns R.L., Ku D.N., Stewart M.T., Ansley J.P., and Coyle K.A. Optimal graft diameter: effect of wall shear stress on vascular healing. J Vasc Surg 10, 326, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zilla P., Moodley L., Scherman J., et al. Remodeling leads to distinctly more intimal hyperplasia in coronary than in infrainguinal vein grafts. J Vasc Surg 55, 1734, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meirson T., Orion E., Di Mario C., et al. Flow patterns in externally stented saphenous vein grafts and development of intimal hyperplasia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 150, 871, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gleason R.L., Gray S.P., Wilson E., and Humphrey J.D. A multiaxial computer-controlled organ culture and biomechanical device for mouse carotid arteries. J Biomech Eng 126, 787, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferruzzi J., Bersi M.R., and Humphrey J.D. Biomechanical phenotyping of central arteries in health and disease: advantages of and methods for murine models. Ann Biomed Eng 41, 1311, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukunishi T., Best C.A., Sugiura T., et al. Tissue-engineered small diameter arterial vascular grafts from cell-free nanofiber PCL/chitosan scaffolds in a sheep model. PLoS One 11, e0158555, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanders R.J., Kempczinski R.F., Hammond W., and DiClementi D. The significance of graft diameter. Surgery 88, 856, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider J.R., Zwolak R.M., Walsh D.B., McDaniel M.D., and Cronenwett J.L. Lack of diameter effect on short-term patency of size-matched Dacron aortobifemoral grafts. J Vasc Surg 13, 785, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thim T., Hagensen M.K., Hørlyck A., et al. Oversized vein grafts develop advanced atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic minipigs. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 12, 24, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weston M.W., Rhee K., and Tarbell J.M. Compliance and diameter mismatch affect the wall shear rate distribution near an end-to-end anastomosis. J Biomech 29, 187, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lardo A.C., Webber S.A., Friehs I., Del Nido P.J., and Cape E.G. Fluid dynamic comparison of intra-atrial and extracardiac total cavopulmonary connections. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 117, 697, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexi-Meskishvili V., Ovroutski S., Ewert P., et al. Optimal conduit size for extracardiac Fontan operation. Eur J Cardio-thoracic Surg 18, 690, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu W., Allen R.A., and Wang Y. Fast-degrading elastomer enables rapid remodeling of a cell-free synthetic graft into a neoartery. Nat Med 18, 1148, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tara S., Kurobe H., Rocco K.A., et al. Well-organized neointima of large-pore poly(l-lactic acid) vascular graft coated with poly(l-lactic-co-ɛ-caprolactone) prevents calcific deposition compared to small-pore electrospun poly(l-lactic acid) graft in a mouse aortic implantation model. Atherosclerosis 237, 684, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roh J.D., Sawh-Martinez R., Brennan M.P., et al. Tissue-engineered vascular grafts transform into mature blood vessels via an inflammation-mediated process of vascular remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 4669, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hibino N., Yi T., Duncan D.R., et al. A critical role for macrophages in neovessel formation and the development of stenosis in tissue-engineered vascular grafts. FASEB J 25, 4253, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller K.S., Lee Y.U., Naito Y., Breuer C.K., and Humphrey J.D. Computational model of the in vivo development of a tissue engineered vein from an implanted polymeric construct. J Biomech 47, 2080, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szafron J.S., Breuer C.K.B., Wang Y., and Humphrey J.D. Stress analysis-driven design of bilayered scaffolds for tissue engineered vascular grafts. J Biomech Eng 139, 121008, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.