Abstract

Diet quality is an important determinant of nutrition and food security and access can be constrained by changes in food prices and affordability. Poverty, malnutrition, and food insecurity are high in Nepal and may have been aggravated by the 2008 food price crisis. To assess the potential impact of the food price crisis on the affordability of a nutritionally adequate diet in the rural plains of Nepal, data on consumption patterns and local food prices were used to construct typical food baskets, consumed by four different wealth groups in Dhanusha district in 2005 and 2008. A modelled diet designed to meet household requirements for energy and essential nutrients at minimum cost, was also constructed using the ‘Cost of Diet’ linear programming tool, developed by Save the Children. Between 2005 and 2008, the cost of the four typical food baskets increased by 19% – 26% and the cost of the nutritionally adequate modelled diet increased by 28%. Typical food baskets of all wealth groups were low in macro and micronutrients. Income data for the four wealth groups in 2005 and 2008 were used to assess diet affordability. The nutritionally adequate diet was not affordable for poorer households in both 2005 and 2008. Due to an increase in household income levels, the affordability scenario did not deteriorate further in 2008. Poverty constrained access to nutritionally adequate diets for rural households in Dhanusha, even before the 2008 food price crisis. Despite increased income in 2008, households remain financially unable to meet their nutritional requirements.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12571-018-0799-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Food price crisis, Nutritionally Adequate Diet, Typical food basket, Poverty, Food security, Malnutrition

Introduction

Although progress has been made in reducing hunger, about 795 million people are still undernourished globally, of whom about 780 million live in developing countries and are unable to access enough food for an active and healthy life (Food and Agriculture Organisation 2015). Diet quality is an important determinant of the food and nutrition security of a population and is influenced by food availability, access, utilisation and affordability at both country and household level. Since food cost is the most important determinant of food purchasing decisions (Lo et al. 2009), a food price rise can exacerbate food insecurity and increase the risk of malnutrition (Martin-Prevel et al. 2012). Low diet quality is often associated with poor socio-economic status (SES). Monsivais et al. (2012) observed that the differential amounts spent among households of different socio-economic backgrounds explained the variable quality of diet. Similarly, a modelling study of diets for French adults found that imposing cost constraints led to a diet plan lower in vitamin C and β–carotene than that of the average population (Darmon et al. 2002). Food prices and income determine purchasing power and the affordability of healthier foods (Drewnowski and Darmon 2005; Darmon and Drewnowski 2008) and may suggest how resilient or vulnerable households can be in responding to a food price crisis. However, the relationship between food price and income is not always predictable, as the larger food environment, i.e. availability, convenience, and desirability of foods in a certain location, can also play important roles (Herforth and Ahmed 2015). It is therefore important to understand and examine the impact of food prices in a given context.

The 2008 food price crisis increased the susceptibility of many vulnerable households to malnutrition, but the effect may have varied around the world due to many factors, including regional variability in price rises, household income levels, consumption patterns, and preferences for available food items (Levine 2012; Mahajan et al. 2015). The World Bank estimated that, globally, food price increases caused an extra 44 million people to be undernourished and 100 million people to fall into poverty (World Bank 2008). Price rises affected the nutritional quality of diets, especially for the lowest income countries and poorer socio-economic groups within a country (Green et al. 2013; Anríquez et al. 2013; Mahajan et al. 2015). One reason for this is that the prices of nutrient-dense food items rose disproportionately and access to higher quality nutritious foods became more restricted among poorer households. Analysis of national level data may mask these differences. In Seattle, USA, the trend in food prices between 2004 and 2008 showed that when foods were grouped by their nutrient density, inflation for the highest quintile was nearly double that of the lowest (Monsivais et al. 2010). In Ghana, the national impact of the 2008 global food price crisis was moderate. However, impact varied by region due to differences in consumption practices and income levels. Poorer households in urban areas who bought most of their food, and those who lived in northern Ghana and spent a large proportion of their income on food, were the worst affected (Cudjoe et al. 2010). Correct assessment of the nutritional impact of a crisis can be difficult, as there is often a lack of geographically detailed price data and methodologically sound studies (Benson et al. 2013; Gibson 2013). To guide program planning and suggest appropriate policy responses in a local context, it is important to understand the extent of local food price inflation and the heterogeneity of the population impacts (Mahajan et al. 2015).

Various measurement tools have been used to understand the differential impact of food prices on food security and nutrition in different regions and among households with varying socio-economic status (Anríquez et al. 2013; Green et al. 2013; Akter and Basher 2014). Economic analysis has been done to measure how the demand for different food groups responds to changes in price (Green et al. 2013). Some studies have focused only on staple prices, whereas price changes could vary for different food groups, and this needs to be considered in assessing the potential nutritional impact of changes in purchasing power (Nordström and Thunström 2011). A food price index based on the prices of items in a typical food basket from a country or region can be used to estimate food price inflation and indicate the magnitude of loss of household purchasing power (Levine 2012). Using data from 35 countries, the World Food Programme estimated that, on average, the cost of a food basket increased by 36% between 2007 and 2008 (Brinkman et al. 2010). In this WFP study, the cost of a food basket in Nepal (for rural and urban areas combined) increased by 19% over one year between 2007 and 2008. However, the study did not assess whether household income had changed or food substitution had occurred.

A food price index typically only takes into account the energy sufficiency of the food basket, rather than its full nutritional adequacy. It is generally made at country or regional level and does not account for household-level socio-economic differences. In addition, a change in food prices needs to be examined in relation to change in income levels to assess potential effects on different groups (Mahajan et al. 2015). The importance of income data was apparent from an analysis in Sri Lanka, which found a 55% increase in food prices, a 26% increase in price of non-food items, but a 57% increase in income between 2007 and 2009. The undernourished proportion of the population was expected to increase by 1.7%, but the predicted increase was much higher when changes in income were not taken into account (Korale-Gedara et al. 2012).

Estimation of the cost of a nutritionally adequate diet using linear programming and household income levels can help model the impact of a food price rise on the affordability of a nutritionally adequate diet and thereby indicate its potential nutritional impact. In several countries, linear programming has been used to plan and estimate the cost of a nutritionally adequate diet for children, men, and women (Briend et al. 2001; Darmon et al. 2002, 2006; Rambeloson et al. 2008; Dibari et al. 2012). The ‘Cost of Diet (CoD)’ tool was developed by Save the Children to help design diets for the whole household (Save the Children UK 2011). The tool can be used to estimate the cost and affordability of a household diet, which can be helpful in understanding the potential for a localized nutritional impact of a crisis among households with different socio-economic backgrounds (Save the Children UK 2009a). Several recent studies have used CoD (Save the Children UK 2009a, b; Frega et al. 2012; Baldi et al. 2013; Save the Children UK 2013a; Geniez et al. 2014; Termote et al. 2014; Biehl et al. 2016), reflecting that it can be used as an advocacy tool to promote food-based interventions or social safety net programmes, depending on the specific context.

In this study, we used local market price data from the rural plains of Nepal before and during the global food price crisis, to estimate the cost, affordability, and nutritional content of typical food baskets (TFB) and a modelled, minimum-cost, nutritionally adequate diet (NAD). The unique features of this study are that, rather than using country or regional level food baskets, we calculated food price inflation based on a local food price index and utilised consumption pattern and income estimates from the area to plan the TFB as well as the modelled NAD. These analyses, although they do not compare regions, are important for Nepal as Shively et al. (2015) found that the relationship between environmental conditions and nutritional status of children varied in different regions. Furthermore, these analyses of impact of price rise on affordability scenarios for the two methods (TFB and NAD) were disaggregated by SES groups, which enabled our study to examine the hypothesis that after adjusting for changes in income, the potential dietary impact of the 2008 global food price crisis would vary by socio-economic group.

Methods

Nepal is a diverse country with varied geography, topography, and related agricultural and consumption practices. It has three ecological zones: Hills, Mountains, and Plains. The Plains occupy the smallest area but have the largest population. The study was conducted in Dhanusha district, which lies in the Plains bordering India and has an area of 1180 Sq. Km (Central Bureau of Statistics 2008). It ranks 43rd out of 75 Districts on the Human Development Index (Programme 2009).

The study categorized the population of Dhanusha into four socio-economic groups (wealth groups) and determined a Typical Food Basket (TFB) for each group, which is detailed in later sections. The TFB included a fixed set of food items and met the energy (kcal) requirements of household members. A minimum-cost, Nutritionally Adequate Diet (NAD) that met the requirements for energy and key nutrients for households in all wealth groups was also formulated using linear programming. We estimated the cost of the TFB and NAD and assessed the affordability for each wealth group, before and after the 2008 global food price crisis.

Data sources and analysis

We combined data collected in Dhanusha, during several studies, by enumerators from Mother and Infant Research Activities (MIRA), a non-governmental organization. These were a household economy approach (HEA) study, data from a household surveillance system (HSS) study, a survey of market prices, and a survey of change in income by sources. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Initial data were collected during March–June 2006 in 60 administrative units, called Village Development Committees (VDC) in Dhanusha, using the HEA method introduced by Save the Children UK (Holzmann et al. 2008). The HEA uses participatory group interviews to assess food security and the actual or predicted impact of a livelihood shock in an area. The HEA data from Dhanusha provided a description of the characteristics of wealth groups (Very poor, Poor, Middle, Better-off) and their distribution within each of the 60 VDC. It described their livelihoods and food security patterns, including the annual consumption of food items and income and expenditure by source for the year 2005 (Akhter 2013). The HEA provided useful data on sources of income and the estimated proportion of cash of food-derived income for each wealth group, but quantification of average income varied and was less reliable. Hence, median expenditure data was determined and considered a reliable proxy estimate for income for each wealth group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Indicators used and sources of data: Household Economy Approach 2006 study

| Instrument | Data type | Respondents | Data collected | Outcome Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household Economy Approach (HEA) | Livelihoods | Wealth group representatives | Ownership of assets, livelihoods, coping mechanisms | A narrative description of wealth groups and their proportions within each VDC |

| Expenditure | Wealth group representatives | Total expenditure by category | Median daily household expenditure | |

| Income | Wealth group representatives | Source of income for wealth groups, as food derived and cash income | % of total income by categories (food derived, cash income) by Wealth groups % contribution of income sources to total cash income by Wealth groups |

|

| Food consumption | Wealth group representatives | Name and amount consumed annually for individual foods within each food group | The most frequently consumed food item by each wealth group | |

| 2005 Price of food items | Vendor/s at the main local market/VDC | Prices of commonly consumed food items | Mean price (Nepalese Rupees)/food item |

Baseline data (mid-September 2006 to mid-April 2007) from a household surveillance system (HSS), on household assets, housing characteristics, and primary sources of staple food (Table 2) were analysed using principal components analysis to create a SES index and rank households from the same 60 VDC. In each of the VDC, the proportion of households estimated to belong in each wealth group was available from HEA data and used to group the ranked households into ‘Very Poor’, ‘Poor’, ‘Middle’, and ‘Better-off’ wealth groups, in each VDC so that the SES characteristics of the wealth groups could be described.

Table 2.

Indicators used and sources of data: Household Surveillance Systems and others

| Instrument | Data type | Respondents | Data utilised | Outcome Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household Surveillance System (HSS) | Assets and housing characteristics | Household representative | Ownership of assets, type of roof and walls of house, primary source of staple food | A ranking of households using an asset index derived by Principal Component Analysis (PCA) |

| HSS | Dietary intake | Household representative | Consumption from food groups in the last 24 h (Food Frequency Questionnaire) | Percentage household-level consumption of food groups by wealth group |

| 2008 Change in Income Study | Change in income by source | Key Informant for income sources | Pay rate/monthly salary by source of income | % change in income source; % change in income by category; % change in total income by wealth group |

| 2008 Food Price Survey | Price of food items | Vendor/s at local markets | Mean prices of commonly consumed food items | Mean price (Nepalese Rupees) of foods |

| Cost of Diet software | Nutritionally adequate diets optimised for minimum cost using linear programming | *Mean price of food items in 2005 and 2008 *Physical Activity level of household members, median income / wealth group in 2005 and 2008 |

Minimum cost of a nutritionally adequate diet for Dhanusha households in 2005 and 2008, and affordability by wealth groups |

*Cost of Diet utilised these data gathered by other means

In 2008, we collected data on changes in income levels. Firstly, HEA data were used to create income profiles for each wealth group, which detailed their sources of income (e.g. income from daily labour, factory work, self-employment such as in a grocery shop, salaried workers, and seasonal migratory work within Nepal and abroad, and Government staff salaries). These were used as a basis for calculating income change. Key informants who were engaged in cash-income activities such as. daily waged labour and self-employment were identified by wealth groups and interviewed about current (2008) and recalled (2005) income levels (Akhter 2013). Using income profiles, data were collected from all VDCs for change in income for the commonly used income categories (e.g. agricultural labour daily pay: n = 60, one per VDC; seasonal migratory income: total n = 55; overseas income from Arab countries: n = 57; Malaysia = 59). Other income data were collected through two key informant interviews per six MIRA unit offices, i.e. maximum of 12 interviews/ income category (e.g. earnings from self-employment such as a snack shop = 10, medicine shop = 11). The monthly salaries of government employees were collected from the District Development Committee office, District Public Health Office and District Education office. The income data was used to calculate the percentage change in income between the two periods, and the change was then used to estimate 2008 income levels. Using median total expenditure as a proxy for income in 2005, we modelled 2008 income data as:

More details of the 2008 income change data collection are included in Appendix 5.

HSS data were collected on the consumption of food groups (cereals, roots and tubers, green and other vegetables, fruits, dairy, fish, meat, eggs, pulses and nuts, sugar and honey, and others, such as spices, tea, or coffee) in the last 24 h were summarised and used to define the dietary intake pattern for each wealth group (Akhter 2013). Food price inflation was estimated using price data collected from retail vendors in the most accessible market in each VDC, in 2005 and 2008 (Sep-Oct). Data were collected from the same VDC markets in both years. Allowing for changes (e.g. closure of markets) between 2005 and 2008, food prices from 48 VDCs (one market / VDC) were utilised. Our study did not adjust for possible difference between farm-gate prices and local market prices, but assumed that since data were collected from the most accessible local markets the differences would not be large. Details of this estimation method are presented elsewhere (Akhter 2013).

Data management and analyses were done in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 16.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 2007), except for linear programming analysis, which was performed using the CoD application (Save the Children 2011; Save the Children 2013a) run using the Solver add-in function in MS-Excel 2003 (Excel 2003). Details of data collection and management are presented elsewhere (Akhter 2013).

Calculation of parameters used for Typical Food Baskets (TFBs) and Nutritionally Adequate Diet (NAD)

Mean food prices

For both 2005 and 2008, after excluding outliers that were either < Q1–1.5*IQR or > Q3 + 1.5*IQR (where Q1 = lower quartile; Q3 = Upper quartile; IQR = Inter Quartile Range) (UK Office for National Statistics 2007), the mean prices of food for each 100 g of purchased item (Web Table 1) were used to estimate the cost of TFB and NAD.

Median household expenditure

Using HEA data, annual household expenditures by wealth group for 2005 were estimated. Median expenditure levels served as a proxy for income (Akhter 2013).

Income level for wealth groups in 2008

The income levels of wealth groups in 2008 were estimated using 2005 expenditure as the base and incorporating changes in income between 2005 and 2008. Details of these calculations are mentioned above (Akhter 2013).

Food composition Tables

A food composition database for 64 commonly available items in Dhanusha was prepared using the USDA National Nutrient database (U.S. Department of Agriculture 2009), the East Asia Food Composition database (Food and Agriculture Organisation 1972) and the Bangladeshi food composition tables (HKI 1988). These food values were inputted into the Cost of Diet (CoD) database (Save the Children UK 2011) and were also used for estimation of the food energy (kcal) in the TFB.

Household demographics and energy requirements

The demographics of a model household, and the energy and nutrient requirements of its members were estimated on the basis of primary data and relevant findings from national and regional studies (Hirai et al. 1993; Food and Agriculture Organisation 2010; Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) 2012). Firstly, based on our HEA findings a model household was defined as including six members: 2 boys (aged 2–3 and 5–6 years), 1 adolescent girl of 13–14, and 3 adults (1 male aged 37, 1 female aged 28, and 1 female aged 45–50) (Akhter 2013). Secondly, the energy requirements of household members were set based on FAO standards and available evidence about physical activity levels (PAL) for Nepal (Sudo et al. 2006; Food and Agriculture Organisation 2004a). For the children and adolescents, habitual activity levels recommended by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (2004a) were used. Both adult men and women aged 20–44 were considered to be moderately active (Food and Agriculture Organisation 2004a; Sudo et al. 2006; Central Bureau of Statistics 2008). The senior woman in the household, aged 45–50, was considered to be lightly active (Akhter 2013).

The PAL and corresponding energy requirements of the household members for both TFB and NAD were calculated using guidelines developed by the joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation in 2001 (Food and Agriculture Organisation 2004b). In addition, the CoD program used in-built requirements set for macro- and micronutrients specific for age, sex, and pregnancy or lactation (Save the Children UK 2013a); (Frega et al. 2012).

The same six members and their age, sex, physiological status, and activity levels were used in the calculation of TFB and NAD. Because there was a paucity of data on whether body size or PAL varied in rural Nepal by wealth status, for the purposes of the analysis we assumed that the energy requirements of households did not vary by wealth group. We considered that, although members of a wealthier household would be heavier than members of a poorer household, the PAL would be lower for wealthier than for poorer households and the energy needs were therefore likely to be approximately equal across wealth groups.

Estimating the cost of household Typical Food Baskets (TFB)

To estimate the cost of a TFB, a daily food basket for an adult male was planned and costed for each wealth group. The weight of each food group to be included was first estimated for the combined wealth groups using data from another study (Hirai et al. 1993). Secondly, this food basket was then adjusted to create 4 wealth group specific food baskets using our HSS 24-h data on food group consumption (Table 3). Thirdly, for each wealth group, the most frequently consumed item/s in a food group (based on HEA data) was selected for inclusion (Akhter 2013). The energy content of the included food items met the requirement for an adult male.

Table 3.

Food items included in the typical daily household food baskets, by wealth group, Dhanusha, Nepal

| Very poor | Poor | Middle | Better-off | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food groups | Item | Amount (g) | Item | Amount (g) | Item | Amount (g) | Item | Amount (g) |

| Cereals | Rice, parboiled | 2331 | Rice, parboiled | 2138 | Rice, fine grain | 2076 | Rice, fine grain | 1703 |

| Whole wheat flour | 278 | Whole wheat flour | 255 | Whole wheat flour | 244 | Wheat flour, fine | 188 | |

| Roots/ tubers | Potato | 582 | Potato | 631 | Potato | 651 | Potato | 664 |

| Coloured vegetables | Red amaranth | 346 | Red amaranth | 382 | Red amaranth | 409 | Red amaranth | 440 |

| Other vegetables | Eggplant | 279 | Eggplant | 309 | Eggplant | 333 | Pointed gourd | 372 |

| Pulses | Kheshari lentil (grass pea) | 105 | Red lentil | 148 | Red lentil | 162 | Yellow split pea | 175 |

| Oil | Mustard oil | 112 | Mustard oil | 124 | Mustard oil | 121 | Mustard oil | 120 |

| Dairy | Cow milk | 359 | Cow milk | 999 | Cow milk | 1553 | Cow milk | 2049 |

| Meat | – | – | – | – | – | – | Chicken, broiler | 77 |

| Fish | Mixed small fishes | 62 | Mixed small fishes | 65 | Fish, Silver carp | 51 | Fish, Silver carp | 49 |

| Others | Yellow mustard | 62 | Yellow mustard | 69 | Yellow mustard | 75 | Yellow mustard | 79 |

| Sugar | – | – | – | – | – | – | Sugar | 216 |

| Fruit | – | – | – | – | – | – | Apple | 90 |

Finally, to estimate the cost of the household TFB, the cost of the food basket for the one adult male was calculated using market price data. This cost (in Nepalese Rupees, per kcal), was then multiplied by the total energy requirement for all household members to give the cost of the household TFB. This process was repeated for each wealth group. The 2005 and 2008 TFB included the same set of food items.

Modelling a minimum-cost, nutritionally adequate diet (NAD)

The Cost of Diet (CoD) tool was run to select the foods and the amount of each food that would meet household requirements for energy (kcal) and nutrients with the objective function set to minimize cost. The CoD generated the lowest cost diet plan for the household that was nutritionally adequate. One NAD was formulated for all four wealth groups.

Nutrient constraints were set so that the NAD would: provide an energy content equal to the sum of the requirements of all household members; provide 30% of household energy requirements from fats; provide at least 100% of the recommended intakes of vitamin A, vitamin C, thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6, folic acid, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, calcium, iron, and zinc (Food and Agriculture Organisation 2004a, b); and would not exceed the recommended safe intake levels for vitamin A, iron, vitamin C, calcium and niacin (Food and Agriculture Organisation 2004a; Save the Children UK 2011).

Food consumption constraints comprised intake limits set for food groups and food items. Food group constraints were set as the minimum and maximum allowable intake from a particular food group per week, based on HSS 24-h dietary recall data, published findings, and anecdotal evidence (Hirai et al. 1993; Food and Agriculture Organisation 2004a). Constraints for food items were defined as the allowable number of portions per person per week. They were all set between 0 and 21 portions per person per week. The average intake of food consumed per meal by a 12–23 month child was considered a reference portion size and the CoD adjusted to the size for each member in relation to their energy requirements Portion sizes for different food types were taken from the CoD manual, when available; if not, the portion size for a similar food type was used (Save the Children UK 2011).

Results

Characteristics of wealth groups

HEA interviews indicated that 25.9%, 31.7%, 33.0%, and 8.5% households in Dhanusha were from Very Poor, Poor, Middle, and Better-off wealth groups, respectively. Livelihoods were dominated by agriculture. Poorer households (Very Poor and Poor) were mostly landless or owned a small amount of land and had limited food production. They relied on agricultural daily-waged labour, paid in cash or grain, or other unstable sources of income. The Middle and Better-off were farming households and had earnings from agricultural production, regular jobs, and overseas remittances (Web Table 2). Median annual household expenditure (a proxy for income) showed a gradient and was almost four times higher among Better-off than Very Poor households (Web Table 2). The percentage of total expenditure on food in 2005 also varied by wealth group (Very Poor 58%; Poor 45%; Middle 32%; Better-off 24%).

Cost and nutritional adequacy of Typical Food Baskets (TFB)

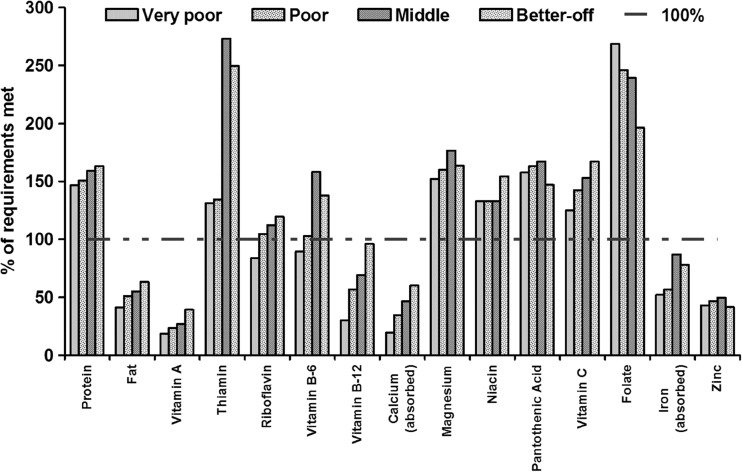

TFB for all wealth groups were assumed to remain constant between 2005 and 2008. They included rice, wheat, potatoes, vegetables, pulses, dairy, and oil, but were more diverse among Better-off households (Table 3). Following the 2008 food price crisis, the absolute costs of the TFB of Very Poor, Poor, Middle, and Better-off households increased by 19.2%, 22.0%, 26.1%, and 23.4%, respectively (Table 4). For both periods, the cost of the TFB for Better-off households was much higher than for poorer households, but the proportion of their income spent on the TFB was much lower. Between 2005 and 2008 the proportion of income spent on food fell for all wealth groups, but the decrease in the proportion of income spent on a TFB was greatest among poorer households (Very Poor, −6.5%; Poor, −3.1%, Middle, −0.3%; Better-off, −1.1%). However, the TFBs of all wealth groups were low in several nutrients, including vitamin A, fats, vitamin B12, calcium, iron, and zinc (Fig. 1). The food basket for the Very Poor was also deficient in riboflavin and vitamin B6.

Table 4.

Cost of a typical daily household food basket in 2005 and 2008, by wealth group, Dhanusha, Nepal

| Wealth group | 2005 | 2008 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost (Nepalese Rupees)a | % of HH Income | Cost (Nepalese Rupees) | % of HH Income | |

| Very Poor | 96.5 | 75.2 | 115.0 | 68.7 |

| Poor | 113.7 | 64.0 | 138.7 | 60.9 |

| Middle | 127.4 | 39.5 | 160.7 | 39.2 |

| Better-off | 167.5 | 30.3 | 206.7 | 29.2 |

Typical household with 6 members: boy (2–3 years), boy (5–6 years), adolescent girl (13–14 years),

adult male (37 years), adult female (28 years), adult female (45–50 years)

a1 US$ = 66.5 Nepalese Rupees in 2005, 73.2 Nepalese Rupees in 2008

Fig. 1.

Nutrient content of a typical daily household food basket, by wealth groups, Dhanusha, Nepal

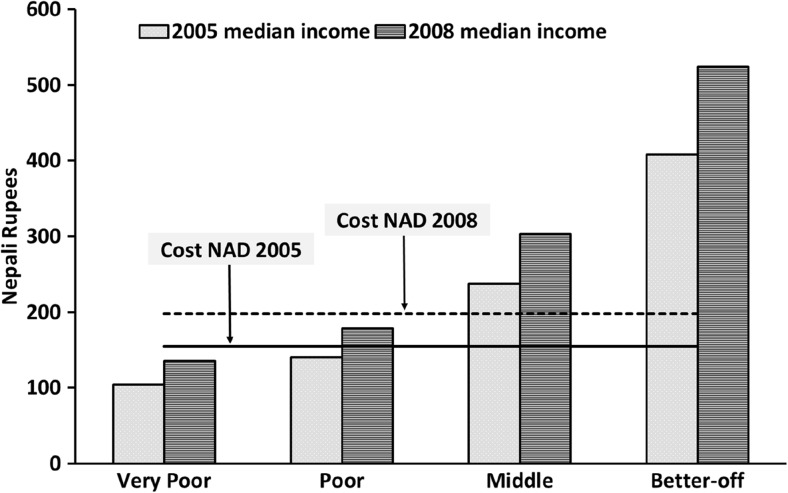

Cost and affordability of a Nutritionally Adequate Diet (NAD)

The CoD linear programming tool generated a minimum cost NAD for the model household, and the cost was calculated for 2005 and 2008 (Table 5). In both years, the NAD met or exceeded the nutritional requirements (Web Table 4) of household members. However, in 2005 neither Very Poor nor Poor households were able to afford a NAD (Fig. 2). In 2008, the cost of the NAD increased by 28% over the 2005 cost, but the incomes of Very Poor, Poor, Middle and Better-off households also increased by 32%, 27%, 25% and 28%, respectively. After the election of the Nepal constituent assembly in 2008, a political decision was taken to increase government salaries with a bias towards the most poorly paid and to establish a minimum wage for agricultural and factory workers (Ministry of Labour and Transport 2008 Nov 18) (Fig. 2). Despite this increase in income, Very Poor and Poor households were still unable to afford a NAD in 2008 (Fig. 2). To afford a NAD, poorer households would need to spend more than their total income on food, whereas Better-off households would need to spend roughly one-third (% income required to purchase a NAD in 2005 and, 2008 for Very poor: 148%, 147%; Poor: 110%, 111%; Middle: 65%, 65%; Better-off: 38%, 38%, respectively).

Table 5.

Content and cost of a nutritionally adequate daily diet for a typical household in Dhanusha in 2005 and 2008, calculated using linear programming

| 2005 | 2008 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Item | Quantity (g) | Cost (Nepalese Rupees) | Quantity (g) | Cost (Nepalese Rupees) |

| Rice, Parboiled | 1456 | 29.0 | 1607 | 36.5 |

| Rice, fine grain (Mansuli) | 353 | 7.6 | 202 | 5.6 |

| Cow Milk | 1621 | 38.1 | 1695 | 45.2 |

| Fish, Rahu | 267 | 30.2 | 277 | 45.3 |

| Mustard oil | 46 | 4.4 | 46 | 6.2 |

| Horse gram | 139 | 4.4 | 139 | 6.6 |

| Potato | 387 | 4.6 | 387 | 5.0 |

| Cumin | 5 | 0.9 | 6 | 1.5 |

| Chilli powder | 33 | 2.6 | 33 | 4.0 |

| GLVa, Amaranth | 975 | 9.2 | – | – |

| GLV, Jute leaves | 319 | 4.8 | 827 | 13.0 |

| Garlic | 65 | 3.3 | 65 | 3.0 |

| Vegetable Ghee | 246 | 15.1 | 244 | 25.6 |

| Total cost | 154.1 | 197.8 | ||

Typical household with 6 members: Boy (2–3 years), Boy (5–6 years), Adolescent girl (13–14 years),

Adult male (37 years), Adult female (28 years), Adult female (45–50 years)

aGreen leafy vegetables

Fig. 2.

Affordability of a minimum-cost, nutritionally adequate diet in 2005 and 2008, by wealth groups, Dhanusha, Nepal

Discussion

We estimated the nutrient content and cost of a TFB, for different wealth groups in a rural district in the plains of Nepal. We estimated the minimum cost of a NAD designed using linear programming and assessed whether the NAD was affordable by different wealth groups, before and after the 2008 global food price crisis.

Although we hypothesised that the food price crisis would have a higher negative nutritional impact on poorer wealth groups, we found that the TFB for all wealth groups did not meet 100% of nutrient requirements. Furthermore, the poorer households could not afford a cost-minimised NAD in both 2005 and 2008. Although the cost of both the TFB and the NAD increased significantly in 2008, the affordability scenario did not deteriorate as an increase in income also occurred. Salaries of government staff in Nepal increased after the Maoist government took over in August 2008, which may have also pushed up payments in other sectors, and a minimum wage rate was established (Ministry of Finance 2009; Akhter 2013). It is important to note that, despite our finding that the price rises were buffered by an immediate increase in incomes, our results indicate that about 57% of households in Dhanusha would have required additional assistance to achieve nutritional adequacy during both periods (Akhter 2013). In addition, when the world food price was falling between 2008 and 2009, there was 19% inflation in food prices in Nepal (Nepal Investment Bank 2009; Food and Agriculture Organisation 2012). Some adverse effects of the price changes may therefore have manifested relatively late in Nepal. The study of Geniez et al. (2014) supports this hypothesis. Using the same tool, they found that 58% of households in the Mountain region and 21% in Kathmandu could not afford a NAD in 2010–2011.

Contrary to our findings, negative impacts of the 2008 food price crisis were seen in a number of countries, especially in low-income countries and low-income groups within them (Ivanic and Martin 2008; Brinkman et al. 2010; Cudjoe et al. 2010; Monsivais et al. 2010; Webb 2010; Mahajan et al. 2015). Several studies have assessed the impact of the 2008 food price crisis using different tools. We used the CoD linear programming tool to formulate a minimum cost, nutritionally adequate household diet and then assessed its affordability. Linear programming has been used more often to model diets at the individual instead of the household level, especially for young children (Briend et al. 2001; Darmon et al. 2002, 2006). Studies have used the CoD software to estimate the cost and affordability of a household diet (Save the Children UK 2009a, 2009b; Frega et al. 2012; Baldi et al. 2013; Save the Children UK 2013b; Geniez et al. 2014) and to advocate promotion of food-based interventions or cash-based social safety net programmes. Consistent with our findings, a least-cost nutritionally adequate diet was unaffordable among poorer households in the pre-crisis period (2005–6) in Ethiopia, Myanmar, and Tanzania (Save the Children UK 2009a). The cost was higher than the average earnings of all wealth groups in Ethiopia, whereas it was higher than the earnings of all ‘very poor’ and some ‘poor’ households in Tanzania and Myanmar (Save the Children 2009a). In Bangladesh, the cost of a least-cost nutritionally adequate diet for 2005/6 and 2007/8 was estimated using the CoD software. The cost increased by 56% and was unaffordable for poorer households in both periods (Save the Children UK 2009b). Estimation of affordability by socio-economic groups in Nepal and other countries highlights the importance of using context-specific data to assess the localized impact of changes in food prices to appropriately guide policy decisions.

Our study found that a typical diet for any wealth group in Dhanusha is still likely to contain less than the recommended intake for several micronutrients, including vitamin A, B12, calcium, iron and zinc; and that the cost of NADs were well above the income levels of poorer households. Although the TFB of Better-off households was more diverse and expensive, it is still low in several micronutrients. Similarly, a study examining the impact of the 2008 food price crisis in Guatemala found disparity in intake among income quintiles, and that households in lower income quintiles were most likely to have diets deficient in vitamin A, B12, folate, and zinc when food prices rise (Iannotti et al. 2012). Assessment of household level dietary diversity using HSS data in Dhanusha (measured by consumption from number of food groups including cereals in the last 24 h) found low diversity among all groups (3.6, 4.0. 4.3 and 4.7 for Very Poor, Poor, Middle and Better-off, respectively) (Akhter 2013). Similar deficiencies were also evident from dietary surveys in rural Nepal (Christian et al. 1998; Parajuli et al. 2012; Ng’eno et al. 2017). A typical food basket generally includes large amounts of rice, providing the bulk of the energy, accompanied by a thin pulse soup, potatoes, and vegetables, with milk as the sole animal origin food (Hirai et al. 1993; Sudo et al. 2006; Parajuli et al. 2012). Ng’eno et al. (2017) examined dietary pattern among socio-economic groups in the plain of Nepal and found that the median daily intake frequencies of most food items were 0 times, but rice, potatoes and vegetable oil were eaten more frequently. Given the low dietary diversity, we only included more than one item per day for cereal and vegetables in the TFB. The number of items per food groups in the TFB was similar to Sudo et al. (2006), which was considered reasonable, based on anecdotal evidence and consultations with field level researchers. We acknowledge that a future study is needed for precise estimation of dietary intake by socio-economic groups, but do not expect that to change our conclusions dramatically.

This lack of diversity in usual diets correlates with the high prevalence of anaemia in the plains of Nepal: 50% in children under five and 42% in women of reproductive age (Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) 2012). The fact that TFB were nutritionally inadequate and that the CoD could generate a NAD from the same local foods that were affordable by the upper two wealth groups suggests that there could be a gap in nutritional knowledge or behaviour, and that for this segment of the population, communication activities that promote increased consumption of micronutrient-rich foods might be beneficial. Beihl et al. (2016) suggested that improving behaviour can increase dietary diversity and nutrient adequacy in the Nepalese population. Based on our data, we suggest that a combination of approaches, such as food supplementation and dietary fortification, introduction of cash-based social safety nets, and behaviour change approaches are required. The Government of Nepal developed a multi-sector nutrition plan in 2012 which also suggested promotion of a combined approach, using direct and indirect nutrition specific initiatives (e.g. micronutrient supplementation, fortification) along with nutrition sensitive initiatives such as cash and in-kind transfers, school feeding, and nutrition education for various target groups (National Planning Commission 2012).

The main strengths of our study are that detailed, local food price data were collected for 64 commonly consumed items in both 2005 and 2008, which allowed estimation of local level food price inflation (Akhter 2013) and examination of how the affordability of a NAD may have been affected by membership of specific wealth groups in the post-crisis period. We collected food prices from the same market locations in the same season (October–November) in both years. We also assessed the nutritional quality of typical food baskets of wealth groups and calculated the cost of a cost-minimised, nutritionally adequate diet, pre- and post-crisis, allowing for a comparison of affordability.

The study had some limitations. Data were not available on changes in food consumption or expenditure on specific food items and it was not possible to examine substitution effects. Food price data were collected during a festive season when prices tend to peak and we were not able to investigate seasonal variation. However, data were collected for commonly consumed food items and we do not expect seasonal price variation to be large enough to change the results dramatically. Another limitation is that our study estimation used prices from the most accessible rural markets, which may have been slightly higher than farm-gate prices. Also, the prices used were per 100 g of purchased food rather than 100 g of edible serving. However, the poorer households needed to spend more than 100% of their income to afford a NAD, whereas consumption of households’ own produce is likely to only play an important role for Middle and Better-off households. It is therefore unrealistic to assume that the factors would significantly change the main results or conclusions. Due to variation in reported income, we used expenditure data as a proxy for income, an approach which has commonly been done in other studies using this tool (Frega et al. 2012; Baldi et al. 2013). The 2008 income level estimates were not generated from household level data, which may have added some inaccuracy. Nevertheless, the estimation used wealth group-specific income sources and changes in incomes between 2005 and 2008. We think that the changes in income data are realistic as key informants engaged in the specific income sources (e.g. government employees, daily labourers, specific self-employment or other professionals) provided the data. Future studies are required to estimate the cost of an adequate diet during different seasons and to check the acceptability and other factors that may affect adoption of a minimum-cost diet generated using the CoD tool.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study found that the typical food baskets of all wealth groups were deficient in micronutrients and the nutritional impact of the food price crisis probably did not vary by wealth group due to an accompanying increase in income. However, the income levels of poorer households, even before the food price crisis, were too low to afford the minimum cost of a nutritionally adequate diet. The inability of poorer households to afford an adequate diet and the inadequacy of nutrients in typical diets indicate that urgent efforts are needed to put in place targeted social safety net programs for poor households, and to provide nutrition education for those households who have the potential to afford nutritional adequacy by making changes to their typical food baskets.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 85.8 kb)

Acknowledgements

A.S., N.A., and N.S. designed the cost and affordability of a nutritionally adequate diet research. The study was embedded in a larger study of nutrition, household economy, and food prices in Dhanusha, designed by N.S., D.M., B.S. and A.C., which B.S. and N.S conducted and managed. N.A. analysed the data and wrote the first draft of the paper. A.S., A.C., N.S., and D.O. contributed to the revisions, and N.A. had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. We thank the participants, the data collectors from MIRA, Sweta Chaudhary who initially processed the HEA data, and Dhanusha District Public Health Office. We acknowledge the support of Esther Busquet and Rachel Evans from Save the Children UK in using the Cost of Diet tool; and thank Suzanne Boyd from the Wolfson Research Institute for Health and Wellbeing, Durham University for help with referencing.

Abbreviations

- CoD

Cost of Diet

- HEA

Household Economy Approach

- HSS

Household Surveillance System

- VDC

Village Development Committee

- PAL

Physical Activity Level

- TFB

Typical Food Basket

- NAD

Nutritionally Adequate Diet

Biographies

Nasima Akhter

is a Post-Doctoral Research Associate in Quantitative methods at Durham University She has over 15 years’ experience in evaluation, monitoring and data analysis. She works across many projects in applied health research including evaluation of interventions and advanced data analysis, teaches statistical concept and analytical methods, facilitates grant applications and provides statistical support to researchers as part of the interdisciplinary statistic group at Wolfson Research Institute of Health and Wellbeing. Nasima obtained her PhD from University College London in 2013, which compared food security and poverty assessment methods, estimated food prices inflation following the 2008 global food price crisis and affordability of a nutritionally adequate diet by socio-economic groups in rural Nepal. Nasima worked as a key researcher for the Helen Keller International Bangladesh’s Nutritional Surveillance Project, Homestead Food Production Program and external evaluation projects (1997 and 2007). She is experienced in design, planning, and implementation of projects and provided consultancy for the WHO, UNHCR, Save the Children.

Naomi Saville

is a Senior Research Associate at University College London Institute for Global Health. She has 26 years research experience and has worked in low-income settings, mostly Nepal, for 23 years. Since 2005 she has worked on maternal and newborn health and nutrition trials in partnership with Mother and Infant Research Activities (MIRA) in Nepal. Naomi completed her degree in Natural Sciences and her PhD in Ecology from Cambridge University in the UK. She has worked in participatory health promotion, community mobilisation, and livelihood diversification through natural resource products and beekeeping in Nepal, India, Somaliland, Sierra Leone and Trinidad and Tobago. Her most recent research investigates how women’s groups, practising participatory learning and action, can improve neonatal survival and maternal and infant nutrition, particularly birth weight.

Bhim Prasad Shrestha

, Senior Programme Manager at Mother and Infant Research activities (MIRA), Dhanusha, Nepal is responsible for overall management and technical support to programmes including financial, human resource, administrative support along with coordination with local, national and international stakeholders. He has also supported MIRA Makawanpur programmes as a Programme Manager and has been working with MIRA since 2000 in various role to support the team capacity in supervisory capacity, and contributed to effective and smooth implementation of MIRA activities. MIRA is a non-governmental organisation (NGO) partnered with the Institute of Child Health (ICH), UCL and has received funding from WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF, to test the effectiveness of interventions to improve maternal and newborn health in rural communities. Before joining MIRA (1990–199), Mr. Shrestha worked with national and international NGOs in Nepal and government agencies to develop capacity of staff and to strengthen project and programmes that aim to improve health in rural communities of Nepal. He is a member of the Nepal Public Health Society and Nepal Red Cross Society. He has a BSc in Public Health and an MSc in Maternal and Child Health from ICH, UCL; and has co-authored a number of health related publications.

Dharma S. Manandhar

is President and Executive Director of Mother and Infant Research Activities (MIRA) – an NGO in Nepal involved in improving maternal and infant health through research, training, advocacy and service. MIRA has been involved in many research activities related to maternal and infant health particularly in large cluster randomized trials in collaboration with the UCL Institute of Global Health over the last two decades. He has been taking part in many nutritional studies, including randomised trials on multiple micronutrient supplementation in the antenatal period, large cluster randomised trials on participatory women’s groups versus participatory women’s groups with food or cash supplementation to pregnant women with the aim of improving birth weight. He has been a co-author of many publications related to maternal and infant nutrition. He has also been Professor and Head of the Department of Paediatrics of Kathmandu Medical College for over a decade and a half and is a member of the Technical Advisory Group of WHO SEARO on Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health. He is also a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, London and Hon. Fellow of the Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health besides other professional societies.

David Osrin

is UCL Professor of Global Health, Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow in Clinical Science, and Honorary Consultant, Great Ormond Street Hospital. A paediatrician and public health researcher, he is interested in interventions to improve the survival and health of women and children in low- and middle-income countries, with an emphasis on urban health. He was based in Nepal from 1998 to 2004, and has lived in India since then. His areas of interest include maternal and child health and nutrition, community-based strategies to improve home care and care-seeking, interventions to improve the quality of health and social services, measuring health and nutrition indicators in underserved populations, and prevention of gender-based violence.

Dr. Anthony Costello

, a renowned international expert on maternal, newborn and child health has headed the Department of Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health at the World Health Organization since September 2015. He is an Honorary Professor and former Director of the UCL Institute for Global Health of International Child Health at the UCL Institute of Child Health; a founding board member of Women and Children First, a UK based NGO which implements maternal and child health programmes in poor populations. He has chaired two Lancet Commissions on Health and Climate Change. His areas of scientific expertise include the evaluation of community interventions to reduce maternal and newborn mortality, neonatal paediatrics, women’s groups, the cost-effectiveness of interventions, nutritional supplementation and international aid for maternal and child health. He has contributed to papers on health economics, health systems, child development, nutrition and infectious disease, and managing the health effects of climate change. He directed programme and project grants funded by the UK Department for International Development, the Wellcome Trust, Saving Newborn Lives Initiative, UBS Foundation, WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, the Big Lottery Fund and the Health Foundation. He has also provided consultancy for Save the Children Fund, the World Bank, WHO, DFID, USAID, UNDP and Saving Newborn Lives. Dr. Costello has been awarded several fellowships: at the Royal College of Physicians, London; Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health; and the Academy of Medical Sciences. He also received the highest honour of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health for his research - the James Spence medal. Dr. Costello has served as UCL Pro-Provost for Africa and the Middle East, and Honorary Consultant Paediatrician at the UCL Hospital for Tropical Diseases and the Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children.

Andrew Seal

is a Senior Lecturer in International Nutrition at UCL and works on nutritional problems in populations affected by disasters and emergencies. He leads the Nutrition in Crisis Research Group, which studies: the Epidemiology of malnutrition in emergency affected populations; Optimisation of food assistance; Diagnosis and management of acute malnutrition; and Approaches to human resource development and capacity building. Recent projects have been funded by DFID, UNHCR, USAID/OFDA, FAO, and the World Food Programme (WFP). He has worked in Bangladesh, Eastern Europe, and many countries in Africa.

Funding

This study was funded by a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award (085417MA/Z/08/Z), and UBS Optimus Foundation. The authors are responsible for the content of this publication, which does not necessarily reflect the views of the funders.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Akhter N. Food and Nutrition security in the rural plains of Nepal: impact of the global food price rise. London: University College London; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Akter, S., & Basher, S. A. (2014). The impacts of food price and income shocks on household food security and economic well-being: Evidence from rural Bangladesh. Global Environmental Change, 25, 150–162, doi:doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.02.003.

- Anríquez G, Daidone S, Mane E. Rising food prices and undernourishment: A cross-country inquiry. Food Policy. 2013;38:190–202. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldi M, Catharina M, Fahmida J, Hardinsyah F, Geniez G, Minarto B, Pee d. Cost of the Diet (CoD) tool: First results from Indonesia and applications for policy discussion on food and nutrition security. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 2013;34(2):S35–S42. doi: 10.1177/15648265130342S105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson, T., Minot, N., Pender, J., Robles, M., & von Braun, J. (2013). Information to guide policy responses to higher global food prices: The data and analyses required. Food Policy, 38, 47–58, 10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.10.001.

- Biehl, E., Klemm, R. D. W., Manohar, S., Webb, P., Gauchan, D., & West, K. P. (2016). What Does It Cost to Improve Household Diets in Nepal? Using the Cost of the Diet Method to Model Lowest Cost Dietary Changes. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 10.1177/0379572116657267. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Briend A, Ferguson E, Darmon N. Local Food Price Analysis by Linear Programming: A New Approach to Assess the Economic Value of Fortified Food Supplements. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 2001;22(2):184–189. doi: 10.1177/156482650102200210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman H-J, de Pee S, Sanogo I, Subran L, Bloem MW. High Food Prices and the Global Financial Crisis Have Reduced Access to Nutritious Food and Worsened Nutritional Status and Health. The Journal of Nutrition. 2010;140(1):153S–161S. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.110767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Bureau of Statistics . Statistical year book Nepal. Kathmandu: National Planning Commission; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Christian P, West KP, Jr, Khatry SK, Katz J, Shrestha SR, Pradhan EK, LeClerq SC, Pokhrel RP. Night blindness of pregnancy in rural Nepal - nutritional and health risks. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;27:231–237. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudjoe G, Breisinger C, Diao X. Local impacts of a global crisis: Food price transmission, consumer welfare and poverty in Ghana. Food Policy. 2010;35(4):294–302. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Does social class predict diet quality? The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;87(5):1107–1117. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmon N, Ferguson EL, Briend A. A cost constraint alone has adverse effects on food selection and nutrient density: an analysis of human diets by linear programming. The Journal of Nutrition. 2002;132(12):3764–3771. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.12.3764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmon N, Ferguson EL, Briend A. Impact of a cost constraint on nutritionally adequate food choices for French women: an analysis by linear programming. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2006;38(2):82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibari F, Diop el HI, Collins S, Seal A. Low-cost, ready-to-use therapeutic foods can be designed using locally available commodities with the aid of linear programming. The Journal of Nutrition. 2012;142(5):955–961. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.156943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A, Darmon N. Food choices and diet costs: an economic analysis. The Journal of Nutrition. 2005;135(4):900–904. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.4.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organisation (1972). Food composition table for use in East Asia 1972. Rome: Food and Agriculture: Agriculture and consumer protection department.

- Food and Agriculture Organisation (2004a). Human Energy Requirements 2001: Report of a joint FAO/WHO/UNI expert consultation. (Vol. Food and Nutrition echnical Report Series 1). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation.

- Food and Agriculture Organisation (2004b). Vitamin and Mineral requirements in human nutrition; report of a joint FAO/WHO expert consultation. (Vol. Second Edition). Geneva: World Health Organisation.

- Food and Agriculture Organisation . Selected indicators of food and agricultural development in the Asia-Pacific region, 1999–2009. Bangkok: FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organisation (2012). World Food Price Index. http://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/foodpricesindex/en/.

- Food and Agriculture Organisation (2015). The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2015. Meeting the 2015 international hunger targets: taking stock of uneven progress. Rome: FAO. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Frega R, Lanfranco JG, De Greve S, Bernardini S, Geniez P, Grede N, et al. What linear programming contributes: world food programme experience with the "cost of the diet" tool. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 2012;33(3 Suppl):S228–S234. doi: 10.1177/15648265120333S212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geniez, P., Mathiassen, A., de Pee, S., Grede, N., & Rose, D. (2014). Integrating food poverty and minimum cost diet methods into a single framework: a case study using a Nepalese household expenditure survey. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 35(2), 151–159. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gibson, J. (2013). The crisis in food price data. Global Food Security, 97–103.

- Green, R., Cornelsen, L., Dangour, A. D., Turner, R., Shankar, B., Mazzocchi, M., et al. (2013). The effect of rising food prices on food consumption: systematic review with meta-regression. BMJ, 346. 10.1136/bmj.f3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Herforth A, Ahmed S. The food environment, its effects on dietary consumption, and potential for measurement within agriculture-nutrition interventions. [journal article] Food Security. 2015;7(3):505–520. doi: 10.1007/s12571-015-0455-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai, K., Nakayama, J., Sonoda, M., Ohno, Y., Okuno, Y., Nagata, K., et al. (1993). Food consumption and nutrient intake and their relationship among nepalese. Nutrition Research, 13(9), 987-994, doi:doi:10.1016/S0271-5317(05)80518-4.

- HKI HKI. Tables of nutrient composition of Bangladeshi foods. Dhaka: Helen Keller International; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Holzmann P, Boudreau T, Holt J, Lawrence M, O'Donnell M. The household economy approach: a guide for programme planners and policy-makers. London: Save the Children and FEG consulting; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Iannotti LL, Robles M, Pachon H, Chiarella C. Food prices and poverty negatively affect micronutrient intakes in Guatemala. The Journal of Nutrition. 2012;142(8):1568–1576. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.157321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanic M, Martin W. Implications of higher global food prices for poverty in low-income countries. Agricultural Economics. 2008;39((suppl)):405–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-0862.2008.00347.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korale-Gedara P, Ratnasiti S, Bandara J. Soaring food prices and food security: Does the income effect matter? Applied Economics Letter. 2012;19:1807–1812. doi: 10.1080/13504851.2012.667538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levine, S. (2012). The 2007/2008 food price acceleration in Namibia: an overview of impacts and policy responses. Food Security, 59–71.

- Lo YT, Chang YH, Lee MS, Wahlqvist ML. Health and nutrition economics: diet costs are associated with diet quality. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;18(4):598–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan S, Sousa-Poza A, Datta KK. Differential effects of rising food prices on Indian households differing in income. [journal article] Food Security. 2015;7(5):1043–1053. doi: 10.1007/s12571-015-0485-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Prevel Y, Becquey E, Tapsoba S, Castan F, Coulibaly D, Fortin S, et al. The 2008 food price crisis negatively affected household food security and dietary diversity in urban Burkina Faso. The Journal of Nutrition. 2012;142(9):1748–1755. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.159996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Microsoft Excel, Version 2003

- Ministry of Finance, M . Budget speech of fiscal year 2008–2009. Kathmandu: Government of Nepal, Ministry of Finance; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP), N. E., ICF International INC (2012). Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Kathmandu: Ministry of Health and Population.

- Ministry of Labour and Transport, G. o. N (2008). Nepal Gazetter (2008), Notice of Government of Nepal (GoN). In P. Ministry of Labour and Transport, Supplementary 25 (e), (Ed.), (pp. 1–3). Singadarbar, Kathmandu: Department of Print.

- Monsivais P, McLain J, Drewnowski A. The rising disparity in the price of healthful foods: 2004-2008. Food Policy. 2010;35(6):514–520. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsivais P, Aggarwal A, Drewnowski A. Are socio-economic disparities in diet quality explained by diet cost? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2012;66(6):530–535. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.122333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Planning Commission, G. o. N (2012). Multi-sector Nutrition Plan (2013- 2017). Kathmandu, Nepal.

- Nepal Investment Bank, L . Investment Bank in Nepal Inflation Report. Kathmandu, Nepal: Research and Development Department, Kathmandu; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ng’eno BN, Perrine CG, Whitehead RD, Subedi GR, Mebrahtu S, Dahal P, et al. High Prevalence of Vitamin B12 Deficiency and No Folate Deficiency in Young Children in Nepal. Nutrients. 2017;9(1):72. doi: 10.3390/nu9010072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordström J, Thunström L. Can targeted food taxes and subsidies improve the diet? Distributional effects among income groups. Food Policy. 2011;36(2):259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.11.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parajuli RP, Umezaki M, Watanabe C. Diet among people in the Terai region of Nepal, an area of micronutrient deficiency. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2012;44(4):401–415. doi: 10.1017/S0021932012000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Programme UND. Nepal Human Development Report 2009: State transformation and human development. Kathmandu: United Nations Development Programme; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rambeloson ZJ, Darmon N, Ferguson EL. Linear programming can help identify practical solutions to improve the nutritional quality of food aid. Public Health Nutrition. 2008;11(4):395–404. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Save the Children UK (2009a). The minimum cost of a healthy diet: findings from piloting a new methodology in four study locations. London: Save the Children UK.

- Save the Children UK (2009b). How the global food crisis is hurting children. Save the Childen uk.

- Save the Children UK (2011). The cost of diet: A practitioner's guide. London: Save the Children UK.

- Save the Children UK (2013a). The Cost of Diet. http://www.heawebsite.org/about-cod.

- Save the Children UK . Pakistan. London: Save the Children; 2013. A cost of the diet analysis in the irrigated rice and wheat producing with labour livelihood zone, Shikarpur. [Google Scholar]

- Shively G, Sununtnasuk C, Brown M. Environmental variability and child growth in Nepal. Health & Place. 2015;35:37–51. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, S. v . SPSS Computer Programme. Chicago: SPSS inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sudo N, Sekiyama M, Maharjan M, Ohtsuka R. Gender differences in dietary intake among adults of Hindu communities in lowland Nepal: assessment of portion sizes and food consumption frequencies. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;60(4):469–477. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Termote C, Raneri J, Deptford A, Cogill B. Assessing the potential of wild foods to reduce the cost of a nutritionally adequate diet: an example from eastern Baringo District, Kenya. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 2014;35(4):458–479. doi: 10.1177/156482651403500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, A. R. S . Composition of foods raw, processed, prepared, USDA national nutrient database for standard reference. Beltsville, Maryland: USDA; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UK Office for National Statistics (2007). Consumer Price Indicies. Technical manual 2007 edition. London: UK Office for National Statistics.

- Webb P. Medium- to long-run implications of high food prices for global nutrition. The Journal of Nutrition. 2010;140(1):143s–147s. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.110536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank, T (2008). Rising food and Fuel Prices: addressing the risks to future generations.: Human Development Network, Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Network.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 85.8 kb)