Abstract

Objective

This meta-analysis was undertaken to estimate the prevalence of diabetic nephropathy and its association with hypertension in diabetics of sub-Saharan African countries.

Results

A total of 27 studies were included for the meta-analysis. The pooled overall prevalence of diabetic nephropathy was 35.3 (95% CI 27.46–43.14). In sub-group analyses by types of diabetes and regions, for instance, the prevalence was 41.4% (95% CI 32.2–50.58%) in type-2 diabetes mellitus and 29.7% (95% CI 14.3–45.1%) in Eastern Africa. Pooled point estimates from included studies revealed an increased risk of diabetic nephropathy with hypertension compared to without hypertension (OR = 1.67, 95% CI 1.31, 2.14). Diabetic nephropathy is a common complication in diabetic patients. Diabetic nephropathy complication is significantly higher in hypertensive patients. A preventive strategy should be adopted or planned to reduce diabetes mellitus and its complication of neuropathy, particularly in hypertensive.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13104-018-3670-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Diabetic nephropathy, Hypertension, Sub-Saharan countries

Introduction

Worldwide, around 387 million people have diabetes mellitus (DM) according to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) update of 2014. Nearly 592 million people, or 1 person in 10, are anticipated to have diabetes in 2035 [1]. Diabetes is the single major cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and consequent dialysis leads to a huge burden in terms of poor quality of life and economical costs [2].

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is an emerging clinical and public health challenge and is related with adverse outcomes including ESRD and heart failure, as well as kidney replacement therapy [3, 4], deaths related to these terminal illnesses [5, 6] by compromising life expectancy [7] in most African countries in particular [3, 4]. Indeed, DN remains higher in African, Asians, and Native Americans as compared to Caucasians [8, 9]. Generally for the past two decades, the prevalence of DN in people with diabetes has not improved because of an increase in the prevalence of reduced eGFR [10]. Likewise, the magnitude of ESRD in DM patients decline faintly [11] and the rate of DN increase is significant perhaps due to higher rates of type 1 and type 2 DM [12, 13]. In Africa, the highest magnitude of DN is associated with late diagnosis, scarcity of screening and diagnostic resources, poor control of blood sugar and other precipitating factors, and inappropriate treatment [14–16].

Various factors may be associated with a worsening renal disease among diabetic patients. Some of the major factors include genetic predisposition [17, 18], improper control of blood sugar [19, 20] and hypertension [21, 22]. There is evidence that both diabetes mellitus and hypertension are extremely interconnected, and in majority of the cases cardiac consequence may be associated with advanced stages of DN. For example, the relationship between hypertension and DN can be explained by the retention of concentrated sodium and subsidiary blood vessel resistance [23]. Saying this, previous studies of the magnitude of DN are remains inconsistent and unclear. Furthermore, to our knowledge, there is no synthesis of existing contemporary evidence on the association between DN and hypertension in diabetic patients. Thus, the aim of this meta-analysis is to estimate the prevalence of DN and examine its association with hypertension among diabetic patients in sub-Saharan African countries.

Main text

Methods

Search strategy and study design

Using computerized databases, searches were performed to locate all studies on the prevalence of DN among diabetic patients in sub-Saharan countries. Databases included from EMBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINHAL), Pub Med, MEDLINE, Google scholar and Google for grey literature. We extended our search by retrieving reference lists of eligible articles, hand searches for grey literature and other relevant literature collections. Observational studies conducted on the prevalence of DN among diabetic patients in sub-Saharan countries were selected for this meta-analysis. Search protocol was formulated by using such common key words as ‘Renal disease OR Renal insufficiency OR Diabetic nephropathy’ OR ‘DN’ OR end stage kidney failure, OR microalbuminuria AND hypertension OR HTN AND diabetes OR diabetes mellitus OR type 1 diabetes OR type 1 DM OR type 2 DM AND ‘sub-Saharan African countries (48 countries). We exhaustively searched by using the above key words in each sub-Saharan country, for instance, in Ethiopia, Botswana, Kenya and E.T.C. To make a certain scientific rigor, we strictly followed the preferred reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guideline [24].

Inclusion criteria

The study inclusion criteria included the following: those studies published in English, where the process of identifying DN was well described, and those studies with sufficient information to estimate the point prevalence of DN. The process of study inclusion is shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S1.

Exclusion criteria

Available studies were excluded if only the DN incidence in follow-up years was reported or when they did not explain the process/criteria of DN diagnosis and inability to access full-text.

Data extraction

All identified studies were screened for inclusion by two reviewers (FW and GDK). Discussions and mutual consensus were in place when possible arguments were raised between the two reviewers. These reviewers then assessed the full text of potentially eligible papers. We made some efforts to communicate primary authors whenever further information was needed. Numerator and denominator data and beta coefficients and their standard errors (if given) were used to calculate ORs, where ORs with 95% CI were not given. The data extraction format included first author, study year, region of study, study design, sample size, diagnostic criteria and types of diabetes. The occurrence of DN and HTN were also extracted from each included study.

Quality appraisal

The included articles were evaluated for quality, with only high quality studies included in the analysis. Two authors (FW, GDK) independently assessed the quality of each included paper. The reviewers compared their quality appraisal scores and resolved any disparity before calculating the final appraisal score. Newcastle–Ottawa Scale adapted for cross-sectional studies quality assessment tool was used [25]. The tool has three sections in general; the first section graded from five stars and due emphasis on the methodological quality of each original study. The second section of the tool explains with the comparability of the study. The third section focus on the outcome and statistical analysis of each original study. Articles with a scale of ≥ 6 out of 10 scales were considered as high quality. Consequently, all eligible studies had high quality scores.

Data analysis

Information about the study design, study sample, etc. were summarized by Microsoft excel. Relevant data were then exported to STATA/se version 14 software for analysis. Meta-analysis of pooled prevalence of DN was carried out using a random-effects model, generating a pooled prevalence with 95% CIs, by using the approach of DerSimonian and Laird statistical method [26]. Heterogeneity among studies was estimated using the Cochran’s Q and I2 statistic and is characterized as low, moderate, or high for 25%, 50%, and 75%, respectively [27]. We also scrutinized forest plots of summary estimates of each study to determine whether we could identify any outlier or heterogeneity. Publication bias was determined based on the symmetry of funnel plots [28], and Egger’s test [29]. Sub-group analyses were carried out by region, sample size and types of DM for there was significant heterogeneity across the included studies.

Results

Flow chart

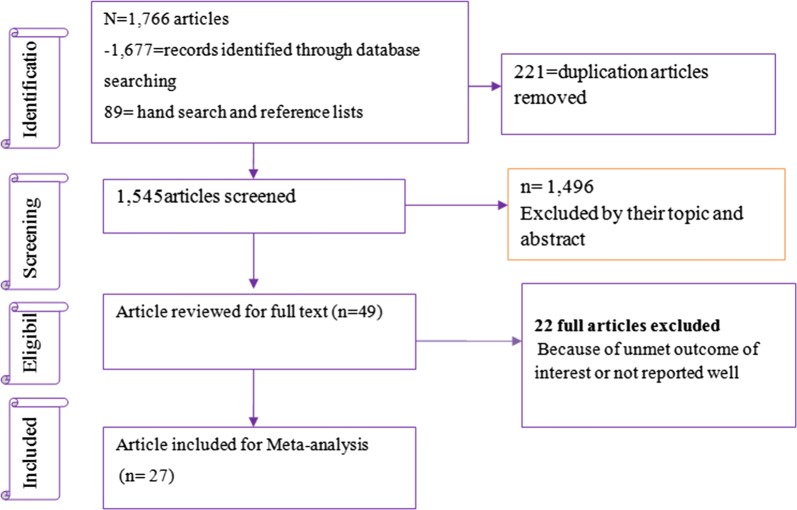

Figure 1 shows the flow chart and selection process of exploring the prevalence of DN among DM patients. Our electronic database search offered 1766 articles, of those 1545 non-duplicate papers were assessed and 1496 excluded after reviewing their title and abstracts.

Fig. 1.

Pooled prevalence of DN among DM patients in sub-Saharan countries

The remaining 49 were examined by full text. Of which, 22 articles were excluded due to unmet outcome of interest; only 27 studies met our inclusion criteria. The characteristics and quality assessment of all included studies are shown in Table 1. Five studies reported odds ratios of the odds of hypertension in diabetic patients. Finally, 27 articles representing 6552 participants met the inclusion criteria (Additional file 1: Fig. S1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies to determine the prevalence of DN and association with hypertension among diabetic patients in sub-Saharan countries

| Authors name | Region | Country | Diagnostic criteria | Types of DM | Study design | Age of subjects | Sample size | No of people with outcome | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rahlenbech [43] | Eastern Africa | Ethiopia | Microalbuminuria | Both types | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 170 | 55 | 32.35 |

| Sobngwi et al. [44] | Central Africa | Cameroon | Microalbuminuria | Both types | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 64 | 34 | 53.13 |

| Motala et al. [45] | Southern Africa | South Africa | Proteinuria | Both types | Cross-sectional | All | 219 | 54 | 24.66 |

| Wanjohi et al. [46] | Eastern Africa | Kenya | Albuminuria | Type 2 | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 100 | 26 | 26.00 |

| Rotchford and Rotchford [31] | Southern Africa | South Africa | Microalbuminuria | Both types | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 254 | 102 | 40.16 |

| Albiosu [47] | Western Africa | Nigeria | Microalbuminuria | Both types | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 342 | 97 | 28.36 |

| Alebiosu et al. [48] | Western Africa | Nigeria | Any sign | Both types | Cross-sectional | Not report | 465 | 191 | 41.08 |

| Agaba et al. [49] | Western Africa | Nigeria | Microalbuminuria | Type-2 | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 65 | 32 | 49.23 |

| Mafundikwa et al. [50] | Eastern Africa | Zimbabwe | Proteinuria | Type-2 | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 75 | 16 | 21.33 |

| Lutale et al. [51] | Eastern Africa | Tanzania | Microalbuminuria | Both types | Cross-sectional | All age | 244 | 26 | 10.66 |

| Majaliiwa et al. [52] | Eastern Africa | Tanzania | Microalbuminuria | Type-1 | Cross-sectional | < 18 | 99 | 29 | 29.29 |

| Rahamtalla et al. [53] | Eastern Africa | Sudan | Nephropathy | Type-2 | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 58 | 26 | 44.83 |

| Rasmussen et al. [54] | Eastern Africa | Zambia | Microalbuminuria | Not-report | Cross-sectional | < 18 | 193 | 24 | 12.44 |

| Tamba et al. [55] | Central Africa | Cameroon | Nephropathy | Type-2 | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 140 | 35 | 25.00 |

| Janmohamed et al. [56] | Eastern Africa | Tanzania | eGFR | Both types | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 369 | 308 | 83.47 |

| Ajayi et al. [57] | Western Africa | Nigeria | eGFR | Type 2 | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 628 | 242 | 38.54 |

| Deribe et al. [58] | Eastern Africa | Ethiopia | eGFR | Not report | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 216 | 19 | 8.80 |

| Fiseha et al. [59] | Eastern Africa | Ethiopia | eGFR | Both types | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 214 | 51 | 23.83 |

| Bunza et al. [60] | Western Africa | Nigeria | Nephropathy | Both types | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 100 | 22 | 22.00 |

| Ngassa et al. [61] | Southern Africa | South Africa | Microalbuminuria | Both types | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 754 | 251 | 33.29 |

| Diouf et al. [62] | Western Africa | Senegal | Microalbuminuria | Type-2 | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 195 | 95 | 48.72 |

| Chukwuani et al. [63] | Western Africa | Nigeria | Microalbuminuria | Type-2 | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 200 | 76 | 38.00 |

| Bekele [64] | Eastern Africa | Ethiopia | Nephropathy | Both types | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 355 | 68 | 19.15 |

| Ufuoma et al. [65] | Western Africa | Nigeria | Microalbuminuria | Type-2 | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 200 | 116 | 58.00 |

| Machinngura et al. [66] | Eastern Africa | Zimbabwe | Nephropathy | Both types | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 344 | 154 | 44.77 |

| Radikara [67] | Southern Africa | Botswana | Nephropathy | Type-2 | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 408 | 259 | 63.48 |

| Marie et al. [30] | Central Africa | Cameroon | Microalbuminuria | Not report | Cross-sectional | ≥ 18 | 81 | 28 | 34.57 |

Characteristics of included studies

A total of 6552 participants were represented by 27 included studies (Table 1), published from 1997 to 2017. Ten studies (37%) reported the prevalence of DN among type-2 diabetic patients. Three studies (11.1%) included all age groups (both children and adults); study exclusively assessed DN among type-1 DM (Table 1).

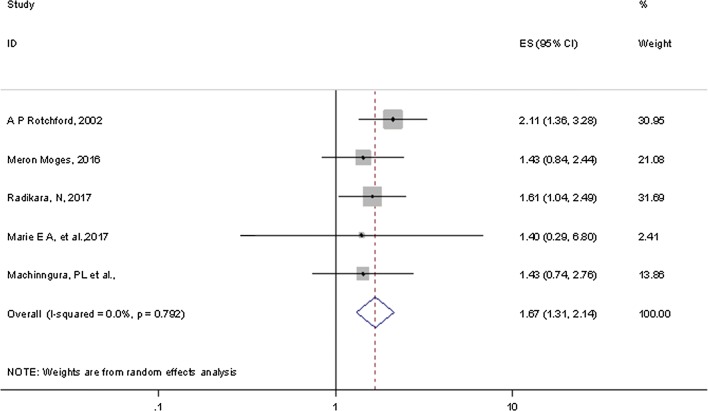

Five studies included determined the effect of hypertension on diabetic nephropathy. These studies reported ORs between 1.4 [30] and 2.11 [31] for the rate of hypertension leading to DN (Additional file 2: Table S1).

Meta-analysis

As presented in the forest plot (Fig. 1), the pooled prevalence of DN among diagnosed DM cases was 35.3 (95% CI 27.46–43.14). The I2 test result indicated high heterogeneity (I2 98.2%, p < 0.001). Thus, a subgroup analysis was done.

Our meta-analysis of the association between DN and hypertension included five studies, all of which reported ORs explicitly. Pooled point estimates from cross-sectional studies showed an increased risk of DN with hypertension compared without hypertension (OR = 1.67, 95% CI 1.31, 2.14). Overall heterogeneity of these studies was not significant (I2 = 0.0%, p = 0.79) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Pooled odds ratio indicating the association of hypertension with DN in diabetic patients

Discussion

DN is becoming universal cause of ESRD and is recognized as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease [32]. Once elevated urinary albumin excretion, it may be inevitable to end with the development of nephropathy, though it may be possible to significantly hinder its development at early stages of the disease. The roles of glucose and blood pressure control may suffice here.

As shown in Additional file 3: Fig. S2, the burden of DN in diabetic patients has been significantly increased from 2015 to 2017. Therefore it needs special attention devotion to minimize the occurrence of the disease.

To our knowledge, this is the first pooled analysis of the prevalence of DN and its association with hypertension in sub-Saharan African countries. Existing evidence from included studies suggest that DN is high among diabetic patients in sub-Saharan countries. It is a study done by Stanford A [33] that revealed adults with type-2DM (n = 2006), with 38.3% having had DN during 2007–2012. Likewise, of the 5072 confirmed diabetes diagnosis, 31% had clinically significant DN, (D2) with microalbuminuria of 31.6 (95% CI 30.6–32.6) [34]. On the other hand, this finding is higher as compared to previous systematic review and meta-analysis done by Elhafeez et al. [35] reporting 24.7% (95% CI 23.6–25.7%) pooled prevalence of DN among diabetic patients [35]. This discrepancy attributed to differences in some factors including study period, sociodemographic characteristics, diagnostic criteria, as well as the methods of measurement of proteinuria and urine collection, diabetic type and duration and varying prevalence of hypertension across studies might contribute for the difference.

We did sub-group analysis due to a significant high heterogeneity. As showed in Additional file 4: Table S2, the prevalence of DN was higher in type-2 DM [41.39% (95% CI 32.2–50.6)] and Southern Africa [40.4% (95% CI 24.1–56.7)], correspondingly (Additional file 4: Table S2).

This study also revealed that hypertension significantly increased the occurrence of DN among people who have a diagnosis of DM. This finding supported by study done Wu B showed that hypertension is a major factors associated with CKD among diabetes patients (OR = 1.78) [33]. Likewise, another study revealed that hypertension is considered to pivotal role for the occurrence of DN [36]. Furthermore, the association between increased blood pressure and DN was recognized by most of the previous studies [37–39]. This could be due to oxidative stress and inflammation process. That is, the evidence suggests local generation of oxidative stress and inflammation is common mechanism in DN pathogenesis in the presence of hypertension and DM. Furthermore, hypertension induced increased intra-glomerular pressure leads to glomerular sclerosis and different renal diseases [40–42].

The overall Egger’s test for publication bias revealed no statistically significant evidence, p value = 0.08.

Conclusion

DN is an ordinary complication in diabetic patients where pooled point estimates showing an increased risk of DN with hypertension. We recommend that a multifactorial approach, including lifestyle modification, Early detection of microalbuminuria, blood glucose control, blood pressure normalization, and the use of treatment that hold up with the RAS (Rennin Angiotensin System) and oxidative stress.

Limitations

However, the findings need to be considered in the context of some important limitations. These include the inclusion of studies published only in English that may cause language bias. Furthermore, due to significant heterogeneity across studies, this study did not determine other possible risk factors contributing for the occurrence of DN in DM patients.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Flow chart describing selection of studies for a meta-analysis of the prevalence of DN and association hypertension among diabetic patients in sub-Saharan Africa.

Additional file 2: Table S1. The effect of hypertension on diabetic nephropathy among diabetes patients.

Additional file 3: Fig. S2. Time trend of DN in sub-Saharan countries from 1997 to 2017.

Additional file 4: Table S2. Subgroup analysis based on region, types of diabetes and sample size among diabetes patients.

Authors’ contributions

FW involved in the conception of the research idea; FW, GDK: undertook data extraction, analysis, interpretation, and manuscript write-up. FW, SE and AAA: undertook acquisition of data, interpreted the results, and drafted the manuscript. AZ, GD, and HM: participated in the study design, acquisition of data and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Debre Markos University library for providing us with a wide range of available online databases.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- DN

diabetic nephropathy

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- HTN

hypertension

- OR

odds ratio

Contributor Information

Fasil Wagnew, Phone: +251-918057206, Email: fasilw.n@gmail.com.

Setegn Eshetie, Email: wolet03.2004@gmail.com.

Getiye Dejenu Kibret, Email: dgetiye@gmail.com.

Abriham Zegeye, Email: abrish189@gmail.com.

Getenet Dessie, Email: ayalew.d16@gmail.com.

Henok Mulugeta, Email: mulugetahenok68@gmail.com.

Amanuel Alemu, Email: amanuel.abajobir@uq.net.au.

References

- 1.CfDCaPNDS Report. Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cosgrove P, Engelgau M, Islam I. Cost-effective approaches to diabetes care and prevention. Diabetes Voice. 2002;47(4):13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu C-Y. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Hare AM, Bertenthal D, Covinsky KE, Landefeld CS, Sen S, Mehta K, Steinman MA, Borzecki A, Walter LC. Mortality risk stratification in chronic kidney disease: one size for all ages? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(3):846–853. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005090986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, Li Z, Naicker S, Plattner B, Saran R, Wang AY-M, Yang C-W. Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet. 2013;382(9888):260–272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60687-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levey AS, Coresh J. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9811):165–180. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritz E. Nephropathy in type 2 diabetes. J Intern Med. 1999;245(2):111–126. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young BA, Maynard C, Boyko EJ. Racial differences in diabetic nephropathy, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in a national population of veterans. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(8):2392–2399. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.8.2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.System URD . USRDS 2003 Annual Data Report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda: National Institute of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Afkarian M, Zelnick LR, Hall YN, Heagerty PJ, Tuttle K, Weiss NS, De Boer IH. Clinical manifestations of kidney disease among US adults with diabetes, 1988–2014. JAMA. 2016;316(6):602–610. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.10924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Boer IH. A new chapter for diabetic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(9):885–887. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1708949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayer-Davis EJ, Lawrence JM, Dabelea D, Divers J, Isom S, Dolan L, Imperatore G, Linder B, Marcovina S, Pettitt DJ. Incidence trends of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among youths, 2002–2012. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(15):1419–1429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, 1988–2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1021–1029. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kengne AP, Echouffo-Tcheugui J-B, Sobngwi E, Mbanya J-C. New insights on diabetes mellitus and obesity in Africa-Part 1: prevalence, pathogenesis and comorbidities. Heart. 2013 doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kengne AP, Sobngwi E, Echouffo-Tcheugui J-B, Mbanya J-C. New insights on diabetes mellitus and obesity in Africa-Part 2: prevention, screening and economic burden. Heart. 2013 doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mbanya JCN, Motala AA, Sobngwi E, Assah FK, Enoru ST. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2010;375(9733):2254–2266. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60550-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindner TH, Mönks D, Wanner C, Berger M. Genetic aspects of diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;63:S186–S191. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s84.24.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seaquist ER, Goetz FC, Rich S, Barbosa J. Familial clustering of diabetic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(18):1161–1165. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198905043201801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adler AI, Stevens RJ, Manley SE, Bilous RW, Cull CA, Holman RR, Group U Development and progression of nephropathy in type 2 diabetes: the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS 64) Kidney Int. 2003;63(1):225–232. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arieff AI. Diabetic Nephropathy and Treatment of Hypertension. In: De Groot LJ, Chrousos G, Dungan K, et al., editors. Endotext [Updated 2013 Jan 20]. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

- 21.Hörl MP, Hörl WH. Hemodialysis-associated hypertension: pathophysiology and therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(2):227–244. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.30542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raile K, Galler A, Hofer S, Herbst A, Dunstheimer D, Busch P, Holl RW. Diabetic nephropathy in 27,805 children, adolescents, and adults with type 1 diabetes: effect of diabetes duration, A1C, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes onset, and sex. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(10):2523–2528. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rask-Madsen C, King GL. Kidney complications: factors that protect the diabetic vasculature. Nat Med. 2010;16(1):40. doi: 10.1038/nm0110-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins J, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):97–111. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marie EAB. Microalbuminuria in diabetic patients in the Bamenda health district. Sci J Clin Med. 2017;6(4):63–67. doi: 10.11648/j.sjcm.20170604.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rotchford A, Rotchford K. Diabetes in rural South Africa—an assessment of care and complications. S Afr Med J. 2002;92(7):536–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Obineche EN, Adem A. Update in diabetic nephropathy. Int J Diabetes Metab. 2005;13(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu B, Bell K, Stanford A, Kern DM, Tunceli O, Vupputuri S, Kalsekar I, Willey V. Understanding CKD among patients with T2DM: prevalence, temporal trends, and treatment patterns—NHANES 2007–2012. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2016;4(1):e000154. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2015-000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yokoyama H, Kawai K, Kobayashi M. Microalbuminuria is common in Japanese type 2 diabetic patients: a nationwide survey from the Japan Diabetes Clinical Data Management Study Group (JDDM 10) Diabetes Care. 2007;30(4):989–992. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ElHafeez SA, Bolignano D, D’Arrigo G, Dounousi E, Tripepi G, Zoccali C. Prevalence and burden of chronic kidney disease among the general population and high-risk groups in Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e015069. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomino Y, Gohda T. The prevalence and management of diabetic nephropathy in Asia. Kidney Dis. 2015;1(1):52–60. doi: 10.1159/000381757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elsharif ME, Abdullha SM, Abdalla SM, AllaElsharif EG. The magnitude of chronic kidney diseases among primary health care attendees in Gezira state, Sudan. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplant. 2013;24(4):807. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.113900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gérard C, Roger KA, Aïda LM, Gaoussou S, Hien KM, Adama L. Epidemiological profile of chronic hemodialysis patients in Ouagadougou. Open J Nephrol. 2016;6(02):29. doi: 10.4236/ojneph.2016.62004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seck SM, Diallo IM, Diagne SIL. Epidemiological patterns of chronic kidney disease in black African elders: a retrospective study in West Africa. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplant. 2013;24(5):1068. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.118104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Faria JBL, Silva KC, de Faria JML. The contribution of hypertension to diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy: the role of inflammation and oxidative stress. Hypertens Res. 2011;34(4):413. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silva KC, Rosales MA, de Faria JBL, de Faria JML. Reduction of inducible nitric oxide synthase via angiotensin receptor blocker prevents the oxidative retinal damage in diabetic hypertensive rats. Curr Eye Res. 2010;35(6):519–528. doi: 10.3109/02713681003664923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stratton I, Cull C, Adler A, Matthews D, Neil H, Holman R. Additive effects of glycaemia and blood pressure exposure on risk of complications in type 2 diabetes: a prospective observational study (UKPDS 75) Diabetologia. 2006;49(8):1761–1769. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0297-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rahlenbeck SI, Gebre-Yohannes A. Prevalence and epidemiology of micro-and macroalbuminuria in Ethiopian diabetic patients. J Diabetes Compl. 1997;11(6):343–349. doi: 10.1016/S1056-8727(96)00122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sobngwi E, Mbanya J-C, Moukouri EN, Ngu KB. Microalbuminuria and retinopathy in a diabetic population of Cameroon. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1999;44(3):191–196. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8227(99)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Motala AA, Pirie FJ, Gouws E, Amod A, Omar MA. Microvascular complications in South African patients with long duration diabetes mellitus. S Afr Med J. 2001;91(11):987–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wanjohi F, Otieno F, Ogola E, Amayo E. Nephropathy in patients with recently diagonised type 2 diabetes mellitus in black Africans. East Afr Med J. 2002;79(8):399–404. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v79i8.8824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alebiosu C. Clinical diabetic nephropathy in a tropical African population. West Afr J Med. 2003;22(2):152–155. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v22i2.27938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alebiosu CO, Odusan O, Jaiyesimi A. Morbidity in relation to stage of diabetic nephropathy in type-2 diabetic patients. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95(11):1042. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agaba E, Agaba P, Puepet F. Prevalence of microalbuminuria in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients in Jos Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2004;33(1):19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mafundikwa A, Ndhlovu C, Gomo Z. The prevalence of diabetic nephropathy in adult patients with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus attending Parirenyatwa Diabetic Clinic, Harare. Cent Afr J Med. 2007;53:1–6. doi: 10.4314/cajm.v53i1-4.62599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lutale JJK, Thordarson H, Abbas ZG, Vetvik K. Microalbuminuria among type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients of African origin in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Nephrol. 2007;8(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Majaliwa ES, Munubhi E, Ramaiya K, Mpembeni R, Sanyiwa A, Mohn A, Chiarelli F. Survey on acute and chronic complications in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes at Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(9):2187–2192. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rahamtalla F, Elagib AA, Mahdi A, Ahmed SM. Prevalence of microalbuminuria among sudanese type 2 diabetic patients at elmusbah center at ombadda—omdurman. IOSR J Pharm. 2012;2(5):51–55. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rasmussen JB, Thomsen JA, Rossing P, Parkinson S, Christensen DL, Bygbjerg IC. Diabetes mellitus, hypertension and albuminuria in rural Zambia: a hospital-based survey. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18(9):1080–1084. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tamba SM, Ewane ME, Bonny A, Muisi CN, Nana E, Ellong A, Mvogo CE, Mandengue SH. Micro and macrovascular complications of diabetes mellitus in Cameroon: risk factors and effect of diabetic check-up-a monocentric observational study. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;15:141. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2013.15.141.2104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Janmohamed MN, Kalluvya SE, Mueller A, Kabangila R, Smart LR, Downs JA, Peck RN. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in diabetic adult out-patients in Tanzania. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14(1):183. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ajayi S, Mamven M, Ojii D. eGFR and chronic kidney disease stages among newly diagnosed asymptomatic hypertensives and diabetics seen in a tertiary health center in Nigeria. Ethn Dis. 2014;24(2):220–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Deribe B, Woldemichael K, Nemera G. Prevalence and factors influencing diabetic foot ulcer among diabetic patients attending Arbaminch Hospital, South Ethiopia. J Diabetes Metab. 2014;5(1):1–7. doi: 10.4172/2155-6156.1000322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fiseha T, Kassim M, Yemane T. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and associated risk factors among diabetic patients in southern Ethiopia. Am J Health Res. 2014;2(4):216–221. doi: 10.11648/j.ajhr.20140204.28. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bunza F, Mainasara A, Dallatu M, Bunza J, Wasagu I. Prevalence of microalbuminuria among diabetic patients in Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital, Sokoto. Bayero J Pure Appl Sci. 2014;7(1):1–5. doi: 10.4314/bajopas.v7i1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ngassa Piotie P, Van Zyl DG, Rheeder P. Diabetic nephropathy in a tertiary care clinic in South Africa: a cross-sectional study. J Endocrinol Metab Diabetes S Afr. 2015;20(1):57–63. doi: 10.1080/16089677.2015.1030858. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Diouf N, Lo G, Sow-Ndoye A, Djité M, Tine J, Diatta A. Evaluation of microalbuminuria and lipid profile among type 2 diabetics. Rev Med Brux. 2015;36(1):10–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chukwuani U, Digban KA, Yovwin GD, Chukwuebuni NJ. Prevalence of chronic complications of type 2 diabetes mellitus in a secondary health centre in Niger Delta, Nigeria. Int J Res Med Sci. 2016;4(4):1080–1085. doi: 10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20160787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bekele MM. College of Health Science School of Public Health. College of Health Science School of Public Health Prevalence and Associated Factors of Chronic Kidney Disease among Diabetic Patients that attend Public Hospitals of Addis Ababa By Meron Moges Bekele Advisors: Dr. Negussie Deyassa Dr. Bisrat Alem A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Addis Ababa University; 2016.

- 65.Ufuoma C, Ngozi JC, Kester AD, Godwin YD. Prevalence and risk factors of microalbuminuria among type 2 diabetes mellitus: a hospital-based study from, Warri, Nigeria. Sahel Med J. 2016;19(1):16. doi: 10.4103/1118-8561.181889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Machingura PI, Chikwasha V, Okwanga PN, Gomo E. Prevalence of and factors associated with nephropathy in diabetic patients attending an outpatient clinic in Harare, Zimbabwe. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96(2):477–482. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Radikara N. The prevalence of chronic kidney disease and associated factors among adult patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who attend the diabetes centre in Gaborone, Botswana. 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Flow chart describing selection of studies for a meta-analysis of the prevalence of DN and association hypertension among diabetic patients in sub-Saharan Africa.

Additional file 2: Table S1. The effect of hypertension on diabetic nephropathy among diabetes patients.

Additional file 3: Fig. S2. Time trend of DN in sub-Saharan countries from 1997 to 2017.

Additional file 4: Table S2. Subgroup analysis based on region, types of diabetes and sample size among diabetes patients.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.