Abstract

Background

Alcohol, tobacco and other drug use (ATOD) among adolescent and young adult couples during prenatal and postnatal periods is a significant public health problem, and couples may mutually influence each others' ATOD behaviors.

Purpose

The current study investigated romantic partner influences on ATOD among adolescent and young adult couples during pregnancy and postnatal periods.

Methods

Participants were 296 young couples in the second or third trimester of pregnancy recruited from OBGYN clinics between July 2007 and February 2011. Participants completed questionnaires at prenatal, 6 months postnatal, and 12 months postnatal periods. Dyadic data analysis was conducted to assess the stability and interdependence of male and female ATOD over time.

Results

Male partner cigarette and marijuana use in the prenatal period significantly predicted female cigarette and marijuana use at 6 months postnatal (b = 0.14, P < 0.01; b = 0.11, P < 0.05, respectively). Male partner marijuana use at 6 months postnatal also significantly predicted female marijuana use at 12 months postnatal (b = 0.11, P < 0.05). Additionally, significant positive correlations were found for partner alcohol and marijuana at pre-pregnancy and 6 months postnatal, and partner cigarette use at pre-pregnancy, 6 months and 12 months postnatal.

Conclusions

Partner ATOD among young fathers, particularly during the prenatal period, may play an important role in subsequent ATOD among young mothers during postnatal periods.

Keywords: public health, relationships, young people

Adolescence and young adulthood are critical periods for the use of alcohol, tobacco and other drugs (ATOD). Nearly all ATOD begins and is established during the adolescent and young adult years.1 ATOD among adolescents and young adults who are pregnant and newly parenting is of particular public health significance because of its effects on family health. ATOD during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of adverse fetal and child development outcomes (e.g. fetal alcohol syndrome, learning disorders).2–4 Infants and young children exposed to cigarette smoke are also at increased risk for developing health problems like pneumonia, bronchitis and asthma.5–7 Furthermore, ATOD use in the postnatal period is associated with more parenting difficulties and increased incidence of child maltreatment.8

ATOD during pregnancy is relatively high among adolescents and young adults. National surveys show that 16% of pregnant women aged 15–17 and 7% of those aged 18–25 use illicit drugs. Reported alcohol use is higher among pregnant women aged 15–17 (17%) compared with those aged 26–44 (10%). Cigarette use is higher among pregnant women aged 15–17 (21%) and 18–25 (22%) than those aged 26–44 (11%).9 Although many women discontinue ATOD during pregnancy, others continue using substances.10 Younger age is associated with an increased risk of resumption to ATOD after pregnancy, with rates often returning to pre-pregnancy levels.10–11 In light of these findings, augmenting our understanding of factors related to ATOD during pregnancy and postnatally among young parents is pertinent, with implications for improving prevention and treatment programs.

Given the strong influence of romantic relationship partners on individual behavior during adolescence and young adulthood,12–13 investigating the mutual influence of ATOD among young mothers and fathers is particularly relevant. Cross-sectional research suggests that frequency of alcohol and cigarette use is correlated within romantic dyads.14–17 However, few studies have examined partner influence on ATOD prospectively. Two studies found that partner cigarette and alcohol use predicted individual use, but another study found no prospective partner influence for alcohol use.17–19 Also among adolescents, greater romantic partner smoking decreased the likelihood of smoking cessation in new smokers.20 Additionally, partner drinking behaviors appear to converge over time.21 For marijuana use, romantic partner influences have not been well investigated, though one study found partner influences on marijuana use approached significance.18 Overall, findings suggest that among adolescents, partner ATOD significantly impacts the other partner's use.

To date, there is a dearth of research examining partner influences on ATOD among adolescent and young adult couples during the prenatal and postnatal periods. One study found that male partner drug use predicted greater resumption of alcohol and marijuana use for adolescent mothers postnatally.10 Regarding pregnant adult couples, partner smoking status has significantly predicted smoking behavior of mothers during pregnancy and postnatally.22–23 Similarly, male partner drinking has been significantly related to maternal drinking prentally,24 and both pregnant adolescents and adults were more likely to report prenatal ATOD if their partner reported ATOD.25 Marijuana use in the prenatal and postnatal periods among couples has not been investigated.

Gender differences in romantic partner effects among young couples have also been found,26 with a few studies showing that females are more susceptible to male partner influences regarding ATOD.12 Significant gender by partner interactions have been found in which male partner alcohol use significantly predicted prospective female use.18 Findings on marijuana use among young couples are similar, with gender by partner interactions approaching significance.18–19 Gender differences in romantic partner effects on ATOD among pregnant and parenting young couples have not been examined.

In summary, previous research suggests that ATOD among young romantic partners is positively correlated, and that substance use behaviors converge over time between dyads. However, there are several gaps in the literature that the current study can address. First, most studies have been cross-sectional; longitudinal research is necessary to better understand these associations over time. Second, ATOD patterns have not been examined among pregnant and parenting adolescent and young adult couples, especially low-income minority couples facing immense health disparities. Furthermore, few studies have investigated a broad range of substances (e.g. alcohol, marijuana, cigarettes), and marijuana use in particular is understudied in pregnant adolescent populations. Most partner influence studies also fail to adopt a full dyadic approach, asking participants to report their partner's behavior. By including both dyad members, we obtain a more complete picture about partner-level influences. Finally, the inclusion of fathers in research during pregnancy is rare and provides an interpersonal perspective on behaviors during this time that cannot be ascertained by examining only mothers.

Current study

The current study aims to investigate individual and romantic partner influences on ATOD among adolescent and young adult couples during the prenatal and postnatal periods (6 months and 12 months postnatal). Based on previous research, we hypothesize that there will be a mutual influence of ATOD among adolescent and young adult couples both concurrently and over time. We also expect that romantic partner influences on ATOD will differ for females and males, with males having a stronger influence on females.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 296 pregnant and parenting adolescent and young adult couples (205 females; 175 males). For females, the average age was 18.7 (SD = 1.6), and for males, it was 21.3 (SD = 4.1). Recruitment occurred in a setting (e.g. urban, community clinic) that traditionally has a high proportion of racial/ethnic minorities; thus, our sample reflects the composition of these clinics. Participants were predominantly African American (42.1%) or Hispanic (42.4%), with 11.1% white and 4.5% some other race/ethnicity. Average years of education for females was 11.8 (SD = 0.91), and for males, it was 11.9 (SD = 1.89). Average household income for females was $13 497 (SD = $15 530), and for males, it was $17 439 (SD = $21 541). For males, 77 were English and Spanish speaking, and 7 were Spanish speaking only; for females, 72 were English and Spanish speaking and none were Spanish speaking only.

Procedure

The current study utilizes data obtained from young couples during prenatal, 6 months postnatal and 12 months postnatal periods. Participants were recruited from obstetrics and gynecology clinics in four hospitals in Connecticut between July 2007 and February 2011. Research staff screened 944 potential couples for participation. Of those couples screened, 413 couples were eligible, and 296 (couples) enrolled in the study (72.2% participation). Participants who enrolled were more likely to be 2 weeks further along in pregnancy at screening compared with those who refused (P < 0.05). Participation did not vary by any other pre-screened demographic characteristic (all P > 0.05). Of our 592 participants, 207 males (70%) and 228 females (77%) completed their 6-month postnatal follow-up assessment, and 239 men (81%) and 261 women (88%) completed 12-month postnatal follow-up assessment.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) females in the second or third trimester of pregnancy; (ii) females: aged 14–21; men: at least age 14; (iii) both dyad members report being in a romantic relationship with each other; (iv) both report being the biological parents of the unborn baby; (v) both agree to participate in the study and (vi) both speak English or Spanish. For Spanish-speaking participants, the interview was translated by Spanish-speaking research assistants and then back-translated.

Written informed consent was obtained by a research staff member at the baseline appointment. Participants completed structured interviews via audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI). All procedures were approved by the Yale University Human Investigation Committee and by Institutional Review Boards at study clinics. Participants were reimbursed $25 at each assessment.

Measures

ATOD in adolescents and their partners was assessed using three items from the Recreational Drug Use Scale pertaining to alcohol, cigarette and marijuana use.27 Participants indicated how often they used each substance during the past 3 months on a 5-point Likert scale. Response choices ranged from 0 (never) to 4 (everyday). ATOD pre-pregnancy was assessed using one item during the prenatal assessment; participants reported frequency of ATOD during the 3 months prior to pregnancy. Responses ranged from 0 (never) to 4 (everyday).

Data analytic strategy

We conducted dyadic analysis to assess the stability and interdependence of male and female ATOD over time using path analysis.28 For this analysis, couple is treated as the unit of analysis (e.g. the sample size is the number of couples). Both male and female scores are modeled to determine stability of each person's own variable (e.g. the effect of male's alcohol use during pregnancy on his own alcohol use at 6 months postnatal) which is also referred to as ‘actor’ effects in dyadic analyses.29 We also examined the interdependence of male and female outcomes (e.g. the effect of male's alcohol use prenatally on female's alcohol use 6 months postnatally), which is also referred to as ‘partner’ effects. Baseline correlations were modeled as the correlations of error terms for 12 months postnatal outcomes.28–29 We also tested delayed effects from pre-pregnancy to postnatal by inspecting modification indices. Significant paths were added to the model. Because standardized solutions using path analysis software are not valid for dyadic data, we manually standardized the data.29 We used Bayesian data imputation to include all participants regardless of whether they missed 6-month and 12-month assessments. Analyses controlled for age, race, parity and income for males and females on 6-month and 12-month outcomes.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Frequency of alcohol, cigarette and marijuana use for young mothers and fathers over time is displayed in Table 1. Of note, 4.7% of females reported using alcohol during the prenatal period, 5.4% reported using marijuana and 16.1% reported using cigarettes.

Table 1.

Substance use in males and females at pre-pregnancy, prenatal, and 6 and 12 months postnatal periods

|

Pre-pregnancy

|

Prenatal

|

6 months postnatal

|

12 months postnatal

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |

| Substance use | ||||||||

| Alcohol | ||||||||

| Never | 156 (52.7%) | 116 (40.0%) | 282 (95.3%) | 135 (46.6%) | 119 (40.2%) | 74 (37.6%) | 129 (52.0%) | 76 (33.6%) |

| Rarely | 89 (30.1%) | 95 (32.8%) | 13 (4.4%) | 87 (30.0%) | 63 (21.3%) | 64 (32.5%) | 80 (32.3%) | 71 (31.4%) |

| Sometimes | 40 (13.5%) | 55 (19.0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 18 (6.1%) | 36 (12.2%) | 49 (24.4%) | 33 (13.3%) | 67 (29.6%) |

| Often | 11 (3.7%) | 18 (6.1%) | — | 14 (4.7%) | 6 (2.0%) | 8 (4.1%) | 5 (2.0%) | 7 (3.1%) |

| Every day | — | 6 (2.0%) | — | 5 (1.7%) | — | 2 (0.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | 5 (2.2%) |

| Marijuana | ||||||||

| Never | 210 (70.9%) | 166 (57.2%) | 280 (94.6%) | 183 (63.1%) | 186 (83.0%) | 131 (66.5%) | 207 (83.5%) | 155 (68.3%) |

| Rarely | 36 (12.2%) | 45 (15.5%) | 12 (4.1%) | 40 (13.8%) | 22 (9.8%) | 20 (10.2%) | 24 (9.7%) | 28 (12.3%) |

| Sometimes | 26 (8.8%) | 34 (11.7%) | 2 (0.7%) | 28 (9.7%) | 9 (4.0%) | 20 (10.2%) | 9 (3.6%) | 26 (11/5%) |

| Often | 16 (5.4%) | 12 (4.1%) | 1 (0.3%) | 16 (5.5%) | 3 (1.3%) | 15 (7.6%) | 5 (1.7%) | 10 (4.4%) |

| Every day | 8 (2.7%) | 33 (11/4%) | 1 (0.3%) | 23 (7.9%) | 4 (1.8%) | 11 (5.6%) | 3 (1.0%) | 8 (3.5%) |

| Cigarettes | ||||||||

| Never | 185 (62/5%) | 154 (53/1%) | 248 (83.8%) | 157 (54.1%) | 147 (65.6%) | 102 (51/8%) | 157 (63.3%) | 111 (49.1%) |

| Rarely | 27 (9.1%) | 43 (14.8%) | 17 (5.7%) | 38 (13.1%) | 15 (6.7%) | 18 (9.1%) | 26 (10.5%) | 36 (15.9%) |

| Sometimes | 20 (6.8%) | 26 (9.0%) | 14 (4.7%) | 32 (11.0%) | 11 (4.9%) | 20 (10.2%) | 20 (8.1%) | 28 (12.4%) |

| Often | 27 (9.1%) | 28 (9.5%) | 6 (2.0%) | 26 (9.0%) | 19 (8.5%) | 16 (8.1%) | 16 (6.5%) | 14 (6.2%) |

| Every day | 37 (12.5%) | 39 (13.4%) | 11 (3.7%) | 37 (12.8%) | 32 (14.3%) | 41 (20.8%) | 29 (11.7%) | 37 (16.4%) |

n (column %) are presented for categorical variables. Substance use reflects use in the past 3 months.

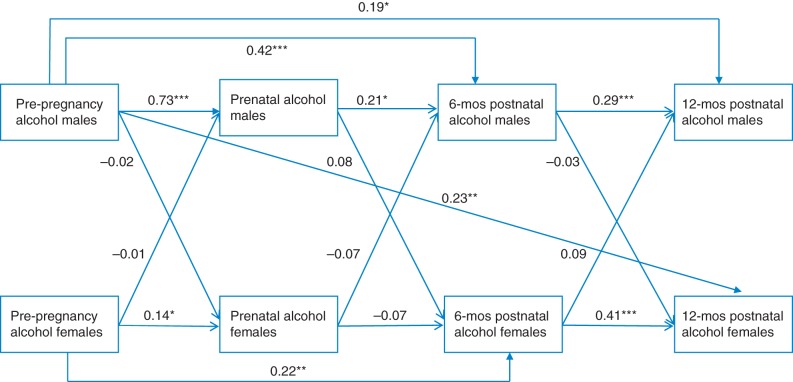

Alcohol

Model 1 examined individual and partner influences on alcohol use concurrently and over time (Fig. 1). For fathers, positive associations were found for alcohol use pre-pregnancy to postnatal (b = 0.73, P < 0.005), prenatal to 6 months postnatal (b = 0.21, P < 0.05) and 6 months to 12 months postnatal (b = 0.29, P < 0.005). There was a delayed effect among males from pre-pregnancy to 6 months postnatal (b = 0.42, P < 0.005) and 12 months postnatal (b = 0.19, P < 0.05). For mothers, positive associations were found for alcohol use pre-pregnancy to prenatal (b = 0.14, P < 0.05) and 6 months to 12 months postnatal (b = 0.41, P < 0.005). There was a significant delayed effect among females from pre-pregnancy to 6 months postnatal (b = 0.22, P < 0.01). Alcohol use pre-pregnancy and 6 months postnatally was also significantly positively correlated between partners (r = 0.28, P < 0.05; r = 0.18, P < 0.05, respectively). Cross-lagged analyses indicated a significant delayed effect for male partner alcohol use pre-pregnancy on female use 12 months postnatally (b = 0.41, P < 0.005).

Fig. 1.

Cross-lagged analysis examining the effects of partner alcohol use over time, controlling for age, race, parity, income and relationship status. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005; Model fit, IFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.05.

Comparison of stability coefficients for alcohol use among males and females showed significant differences from pre-pregnancy to prenatal (χ² difference = 173.60, P < 0.001); alcohol use among fathers was significantly more stable compared with that of mothers. No significant differences in male and female alcohol use stability coefficients were found from prenatal to 6 months (χ² difference = 2.20, ns) or 6 months to 12 months postnatal (χ² difference = 0.70, ns).

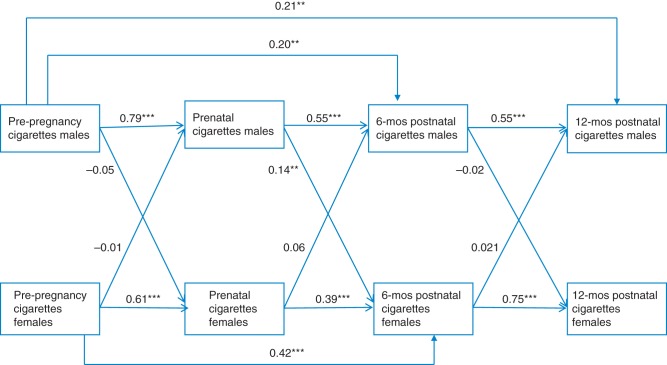

Cigarettes

Model 2 examined individual and partner influences on cigarette use concurrently and over time (Fig. 2). For fathers, positive associations were found for cigarette use pre-pregnancy to prenatal (b = 0.79, P < 0.005), prenatal to 6 months postnatal (b = 0.55, P < 0.005) and 6 months to 12 months postnatal (b = 0.55, P < 0.005). There was a significant delayed effect for male cigarette use pre-pregnancy to 6 months postnatal (b = 0.20, P < 0.01) and 12 months postnatal (b = 0.21, P < 0.01). For mothers, positive associations were found for cigarette use pre-pregnancy to prenatal (b = 0.61, P < 0.005), prenatal to 6 months postnatal (b = 0.39, P < 0.005), and 6 months to 12 months postnatal (b = 0.75, P < 0.005). There was also a delayed effect among mothers for cigarette use pre-pregnancy to 6 months postnatal (b = 0.42, P < 0.005). Cigarette use was significantly positively correlated between partners at pre-pregnancy (r = 0.31, P < 0.05), pregnancy (r = 0.33, P =0.05), 6 months postnatal (r = 0.29, P < 0.05) and 12 months postnatal (r = 0.16, P < 0.05). Cross-lagged analyses indicated that male prenatal cigarette use significantly predicted female cigarette use 6 months postnatally (b = 0.14, P < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Cross-lagged analysis examining the effects of partner cigarette use over time, controlling for age, race, parity, income and relationship status. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005. Fit: IFI = 0.90; RMSEA = 0.071.

Comparison of stability coefficients for cigarette use showed significant differences from pre-pregnancy to prenatal (χ² difference = 57.80, P < 0.001) and from 6 months to 12 months postnatal (χ² difference = 7.00, P < 0.05). Cigarette use was significantly more stable among fathers than mothers from pre-pregnancy to prenatal, whereas it was significantly more stable among young mothers than fathers between 6 and 12 months postnatal. No significant differences were found between male and female stability coefficients for cigarette use from prenatal to 6 months postnatal (χ² difference = 0.01, ns).

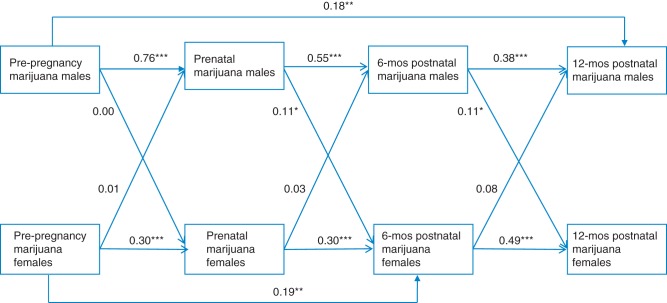

Marijuana use

Model 3 examined individual and partner influences on marijuana use concurrently and over time (Fig. 3). For fathers, significant associations were found for marijuana use pre-pregnancy to prenatal (b = 0.76, P < 0.005), prenatal to 6 months postnatal (b = 0.55, P < 0.005) and 6 months to 12 months postnatal (b = 0.38, P < 0.005). A significant delayed effect was found for marijuana use among males from pre-pregnancy to 12 months postnatal (b = 0.18, P < 0.01). For mothers, positive associations were found for marijuana use pre-pregnancy to prenatal (b = 0.30, P < 0.005), prenatal to 6 months postnatal (b = 0.30, P < 0.005) and 6 months to 12 months postnatal (b = .49, P < 0.005). A significant delayed effect for marijuana was found among mothers from pre-pregnancy to 6 months postnatal (b = 0.19, P < 0.01). Marijuana use was significantly positively correlated between partners at pre-pregnancy (r = 0.27, P < 0.05) and 6 months postnatal (r = 0.17, P < 0.05). Cross-lagged analyses indicated that prenatal male marijuana use significantly predicted female use 6 months postnatal (b = 0.11, P < 0.05), and male use 6 months postnatal predicted female use 12 months postnatal (b = 0.11, P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Cross-lagged analysis examining the effects of partner marijuana use over time, controlling for age, race, parity, income and relationship status. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005; Model Fit: IFI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.039.

Comparison of stability coefficients for marijuana showed significant differences from pre-pregnancy to prenatal (χ² difference = 152.00, P < 0.001); male marijuana use was significantly more stable than female marijuana use. No significant differences in male and female marijuana use stability coefficients were found from prenatal to 6 months postnatal (χ² difference = 3.00, ns) or from 6 months to 12 months postnatal (χ² difference = 2.30, ns).

Discussion

This study examined partner influences on ATOD among adolescent and young adult couples during the prenatal and postnatal periods. We hypothesized that there would be a mutual influence of ATOD among young parents both concurrently and over time. In support of our hypotheses, we found that ATOD among pregnant and parenting young couples is highly correlated, and male partner ATOD, particularly during the prenatal period, plays a significant role in subsequent ATOD among young mothers.

Main findings of this study

Consistent with previous research, our findings indicate that partner ATOD is significantly correlated.26–31 Two mechanisms have been proposed to explain partner correlation in substance use: (i) assortative mating and (2ii) behavior contagion. Assortative mating is non-random pairing whereby individuals choose partners who are already similar to themselves in terms of substance use or attitudes towards substance use behaviors. Alternatively, behavior contagion can also occur whereby a partner's use influences substance use behaviors in the other partner.26 Though we cannot determine whether these mechanisms contributed to patterns of ATOD in our study, they both provide a plausible framework for understanding study findings. Adolescents and young adults may have selected partners with similar ATOD behaviors or attitudes towards ATOD, or the social, emotional and economic disruption that often occurs during the postpartum period may trigger a partner's substance use, which then influences ATOD among the other partner.

We also found that cigarette and marijuana use among young fathers during pregnancy was significantly associated with subsequent cigarette and marijuana use among their partners, whereas young mothers' substance use did not influence their partners' substance use. Male partner ATOD appears to have a stronger influence on partner substance use behavior than female partner ATOD. These findings parallel previous research on male partner influences on female partner ATOD among newly married couples.32–33 Differential influences on alcohol use between adolescent couples have also been found, with male alcohol use significantly predicting female use.16–17

The greater influence of male partner ATOD on female partner ATOD might be related to gender differences in socialization effects, in that females are more likely to modify their ATOD patterns to match their partners to preserve or enhance the relationship.33 Young mothers whose partners smoke may be more likely to smoke to be more social and more compatible with their partner.32 Furthermore, newly parenting young mothers may be particularly susceptible to these socialization influences, because motivations to maintain relationship satisfaction and commitment are likely increased in the context of raising children.

It is also possible that the stronger partner influence on female ATOD is a function of gender differences in reactivity to drug-related cues (i.e. cue reactivity). Females are more sensitive to environmental cues and have a higher reactivity to drug-related stimuli.34–35 If partners use drugs together, drug-related cues such as the smell of cigarette and marijuana smoke might be more likely to trigger use for female partners than male partners. Sensitivity to drug-related stimuli may be augmented for young mothers who have abstained from ATOD during pregnancy but have been exposed to drug-related cues through their male partners, thus increasing the likelihood that they will resume ATOD in the postnatal period. To this point, the greater male partner influence could also be partially explained by the low prevalence of female ATOD, particularly during pregnancy.

Finally, we found significant gender differences in the stability of alcohol and cigarette use from pre-pregnancy to prenatal and from prenatal to 6 months postnatal. Due to concerns about fetal health and development, young mothers may reduce or abstain from ATOD during pregnancy. However, the difference in stability from prenatal to 6 months postnatal reflects an increase in alcohol and cigarette use among mothers. This finding is consistent with previous research showing that many women resume ATOD following childbirth.10–11 In light of the significant effects of male ATOD on female ATOD from prenatal to 6 months postnatal, it is also important to note that young fathers remain fairly consistent with their ATOD during this period. For young mothers who reduce or abstain from ATOD during pregnancy, having a partner who makes little change in ATOD may increase the risk of reinitiating ATOD (particularly alcohol and cigarettes) postnatally.

What is already known

Previous research shows that ATOD is fairly high among adolescents and young adults during pregnancy and postnally. Romantic relationship partners have a strong influence on individual behavior during adolescence, including ATOD behaviors. Alcohol and cigarette use is often correlated between adolescent and young adult romantic dyads, and partner ATOD behaviors converge over time, with a greater influence of male partners on female ATOD than vice versa.

What this study adds

The present study furthers our understanding of the mutual influence of partners in predicting ATOD among adolescent and young adult couples over time, through prenatal and postnatal periods. In particular, the prenatal period may represent a critical window during which reducing substance use among fathers has a strong impact on preventing initiation or relapse among mothers in postnatal periods. Findings from the current study also have important implications for substance use interventions targeting pregnant and newly parenting adolescent and young adult couples. Couples-based interventions, particularly for cigarette and marijuana use, may be more effective in reducing maternal ATOD postnatally if they target ATOD among male partners during the prenatal period.

Limitations of this study

A few limitations should be noted. We did not assess quantity or duration of ATOD, thus somewhat limiting our ability to determine severity of substance use behaviors. Future studies would benefit from including measures of ATOD behavior that assess daily or weekly frequency, quantity and severity, as well as measures of alcohol and substance use-related problems. We also used self-report measures; self-presentation biases may have influenced participant responses. The relatively low rates of ATOD among females, though expected during prenatal and postnatal periods, may also have influenced findings. Finally, study findings may not generalize to other pregnant and parenting adolescent and young adult populations due to specificity of our sample (e.g. ethnicity, socioeconomic status).

Funding

The current study was supported by a National Institutes of Mental Health grant (1R01MH75685) (Kershaw:PI).

References

- 1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings (No. HHS Publication No (SMA) 12–4713). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gaysina D, Ferguson DM, Leve LD et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring conduct problems: Evidence from 3 independent genetically sensitive research designs. JAMA 2013; E1-E8. http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/ (18 March 2013, date last accessed). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mund M, Louwen F, Klingelhoefer D et al. Smoking and pregnancy: a review on the first major environmental risk factor of the unborn. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013;10:6485–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hoyme HE, May PA, Kalberg WO et al. A practical clinical approach to diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: clarification of the 1996 institute of medicine criteria. Pediatrics 2005;115(1):39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DiFranza JR, Aligne CA, Weitzman M. Prenatal and postnatal environmental tobacco smoke exposure and children's health. Pediatrics 2004;113(4):1007–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Herrmann M, King K, Weitzman M. Prenatal tobacco smoke and postnatal secondhand smoke exposure and child neurodevelopment. Curr Opin Pediatr 2008;20(2):184–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hofhuis W, de Jongste JC, Merkus P. Adverse health effects of prenatal and postnatal tobacco smoke exposure on children. Arch Dis Child 2003;88(12):1086–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barnard M, McKeganey N. The impact of parental problem drug use on children: what is the problem and what can be done to help? Addiction 2004;99:552–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Topics in Brief: Prenatal Exposure and Drugs to Abuse, May 2011. http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/topics-in-brief/prenatal-exposure-to-drugs-abuse (18 March 2013, date last accessed).

- 10. Spears GV, Stein JA, Koniak-Griffin D. Latent growth trajectories of substance use among pregnant and parenting adolescents. Psychol Addict Behav 2010;24:322–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bailey J, Hill K, Hawkins J et al. Men's and women's patterns of substance use around pregnancy. Birth 2008;35:50–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haynie DL, Giordano PC, Manning WD et al. Adolescent romantic relationships and delinquency involvement. Criminology 2005;39:106–36. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Furman W, Simon VA. Actor and partner effects of adolescents’ romantic working models and styles of interactions with romantic partners. Child Dev 2006;77:588–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fleming CB, White HR, Catalano RF. Romantic relationships and substance use in early adulthood: An examination of the influences of relationship type, partner substance use, and relationship quality. J Health Soc Behav 2010;51:153–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mermelstein RJ, Colvin PJ, Klingemann SD. Dating and changes in adolescent cigarette smoking: does partner smoking behavior matter? Nicotine Tob Res 2009;11(10):1226–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wiersma JD, Fischer JL, Cleveland HH et al. Selection and socialization of drinking among young adult dating, cohabiting, and married partners. J Soc Pers Relat 2010;28:182–200. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van der Zwaluw CS, Scholte RHH, Vermulst AA et al. The crown of love: intimate relations and alcohol use in adolescence. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009;18(7):407–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alasma MC, Carpentier MY, Azzouz F et al. Longitudinal effects of health-harming and health-protective behaviors within adolescent romantic dyads. Soc Sci Med 2012;74(9):1444–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gudonis-Miller LC, Lewis L, Tong Y et al. Adolescent romantic couples influence on substance use in young adulthood. J Adolesc 2012;35(3):638–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kennedy DP, Tucker JS, Pollard MS et al. Adolescent romantic relationships and change in smoking status. Addict Behav 2011;36(4):320–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kreager DA, Haynie DL, Hopfer S. Dating and substance use in adolescent peer networks: a replication and extension. Addiction 2012;108:638–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hemsing N, Greaves L, O'Leary R et al. Partner support for smoking cessation during pregnancy: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res 2012;14(7):767–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xu H, Wen LM, Baur LA. Smoking status and factors associated with smoking of first-time mothers during pregnancy and postpartum: findings from the Healthy Beginnings Trial. Matern Child Health 2013;17(6):1151–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bakhireva LN, Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson A et al. Paternal drinking, intimate relationship quality, and alcohol consumption in pregnant Ukranian women. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2011;72(4):536–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Perriera KM, Cortes KE. Race/ethnicity and nativity differences in alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy. Am J Public Health 2006;96(9):1629–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rhule-Louie DM, McMahon RJ. Problem behavior and romantic relationships: assortative mating, behavior contagion, and desistance. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2007;10(1):53–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Halkitis PN, Parsons JT. Recreational drug use and HIV-risk sexual behavior among men frequenting gay social venues. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv 2002;14:19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cook WL, Kenny DA. The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model: a model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. Int J Behav Dev 2005;29:101–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic Data Analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Segrin C, Badger T, Dorros SM et al. Interdependent anxiety and psychological distress in women with breast cancer and their partners. Psychooncology 2007;16(7):634–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Umberson D, Montez JK. Social Relationships and Health. J Health Soc Behav 2010;51(1 Suppl):S54–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Homish GG, Leonard KE. Spousal influence on smoking behaviors in a US community sample of newly married couples. Soc Sci Med 1982;61(12):2557–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leonard KE, Mudar P. Peer and partner drinking and the transition to marriage: a longitudinal examination of selection and influence processes. Psychol Addict Behav 2003;17:115–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Field M, Duka T. Cue reactivity in smokers: the effects of perceived cigarette availability and gender. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2004;78(3):647–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Niaura R, Shadel WG, Abrams DB et al. Individual differences in cue reactivity among smokers trying to quit: effects of gender and cue type. Addict Behav 1998;23:209–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]