Abstract

Purpose

To determine whether a reduction in the intensity of Total Therapy (TT) reduces toxicity and maintains efficacy.

Experimental design

289 patients with gene expression profiling (GEP70)-defined low-risk multiple myeloma (LRMM) were randomized between a standard arm (TT4-S) and a light arm (TT4-L). TT4-L employed 1 instead of 2 inductions and consolidations. To compensate for potential loss of efficacy of TT4-L, bortezomib and thalidomide were added to fractionated melphalan 50mg/m2/d × 4.

Results

Grade ≥3 toxicities and treatment-related mortalities were not reduced in TT4-L. Complete response (CR) rates were virtually identical (p=0.2; TT4-S, 59%: TT4-L, 61% at 2 years), although CR duration was superior with TT4-S (p=0.05; TT4-S, 87%;TT4-L, 81% at 2 years. With a median follow-up of 4.5yr, there was no difference in overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). While metaphase cytogenetic abnormalities (CA) tended to be an adverse feature in TT4-S, as with predecessor TT trials, the reverse applied to TT4-L. Employing historical TT3a as training and TT3b as test set, 51 gene probes (GEP51) significantly differentiated the presence and absence of CA (q<0.0001), 7 of which function in DNA replication, recombination, and repair. Applying the GEP51 model to clinical outcomes, OS and PFS were significantly inferior with GEP51/CA in TT4-S; such difference was not observed in TT4-L.

Conclusions

We identified a prognostic CA-linked GEP51 signature, the adversity of which could be overcome by potentially synergizing anti-MM effects of melphalan and bortezomib. These exploratory findings require confirmation in a prospective randomized trial.

Introduction

With the incorporation of novel agents into auto-transplant-supported high-dose melphalan trials, the outlook of patients with multiple myeloma (MM) has greatly improved. In our Total Therapy (TT) program, applying all MM-active agents up-front in order to reduce or even eliminate the development or survival of drug-resistant sub-clones, major advances have been linked to the addition of thalidomide in TT2 and bortezomib in TT3 (1, 2). However, when examined in the context of gene-expression profiling (GEP) of CD138-purified plasma cells, such benefit was limited to the 85% of patients presenting with GEP70-based low-risk MM (LR-MM) (3, 4).In recognition of the lack of progress in high-risk MM (HR-MM), we decided in 2008 to assign low and high risk patients to separate protocols. We are now reporting on clinical outcomes of 289 patients with LR-MM enrolled in a randomized phase III trial of Total Therapy 4 (TT4), comparing a light arm (TT4-L) to a standard arm (TT4-S), with the goal of reducing toxicity while maintaining efficacy in TT4-L.

Materials and Methods

The protocol schema is portrayed in supplementary table 1. Briefly, eligible patients with GEP70-defined LR-MM were randomized between TT4-S and TT4-L. TT4 induction in both arms was similar to TT3b except for the addition of melphalan 10mg/m2 test-dosing 48hr following bortezomib 1.0mg/m2 test-dosing for the purpose of pharmacogenomic investigations (5, 6). TT4-L differed from TT4-S by reduction from 2 cycles to 1 cycle each of induction with M-VTD-PACE prior to and consolidation with dose-reduced VTD-PACE after tandem transplants. The transplant regimen in L-TT4 was altered from a single melphalan dose of 200mg/m2 (MEL200) in TT4-S to a fractionated 50mg/m2/d × 4d (MEL50×4) schedule with the aim to avoid peak MEL dose levels and reduce mucosal toxicity. To compensate for the potentially reduced efficacy of this strategy, bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone (VTD) were added to the fractionated MEL to exploit the observed synergism between MEL and VTD (7, 8). Maintenance therapy was with bortezomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone (VRD) in both arms for 3 years. Two-hundred eighty-nine patients were randomized (TT4-S, n=145; TT4-L, n=144) and stratified by ISS stage and the presence of metaphase cytogenetic abnormalities (CA). Metaphase abnormalities were deemed to be present if at least 2 cells with the same karyotype were present. Protocol eligibility included age >18yr and =<75yr and normal cardio-pulmonary function; liver function tests could be up to twice normal; and creatinine levels up to 3mg/dL were acceptable. Patients had to have active and measurable MM fulfilling CRAB criteria (9). All patients had to sign a written informed consent in keeping with institutional, national and Helsinki Declaration guidelines. The protocol and its revisions had been approved by the institutional review board, which received annual progress reports. As TT4 was supported with a grant from the National Cancer Institute, a Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) reviewed toxicities and efficacies at least annually. We also had independent data audits every 6 to 8 months to verify adherence to protocol stipulations, examine pharmacy records and informed consents, and verify recorded toxicities especially causes of death (COD) and clinical efficacy in terms of complete response (CR) and CR duration (CRD), progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).

Patient work up was per protocol and was similar to our practice in TT3 (2). Special studies included GEP of plasma cells (GEP-PC) and whole bone marrow biopsies GEP-BMBX), procured from both random iliac crest sites and from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-defined focal lesions under computer-assisted tomography guidance. Random bone marrow samples were submitted for metaphase cytogenetic analysis and interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for the detection of deletion 17 p and amplification of 1q21. The protocol called for serial short-term and longer-term studies of GEP and MRI as well as 18-fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET). Pharmacogenomic studies called for repeat GEP sampling from random iliac crest bone marrow and MRI-defined focal lesion(s) 48 hours after test-dosing with bortezomib 1.0mg/m2 and again 48 hours after test-dosing with melphalan 10mg/m2 prior to starting the full VTD-PACE program. PET follow-up studies were scheduled on day 5 after commencing VTD-PACE and prior to first transplantation. These correlative studies will be the subject of a separate report. Most patients were treated in the outpatient setting and were checked daily by MM-experienced nursing staff and weekly by their physicians. Hematopoietic progenitor collection was started when CD34 collection criteria were met with the goal to procure at least 20 million CD34 cells per kilogram body weight.

The primary clinical endpoint was reduction in toxicity in TT4-L versus TT4-S. Secondary endpoints included complete response (CR) defined according to IMWG criteria, the duration of which was measured from its onset to progression or death (10). Overall survival (OS) was calculated from registration until the date of death. Progression-free survival (PFS) was similarly calculated, but also incorporated progressive disease as an event. Time to progression (TTP) was measured from registration until the date of progression or relapse, whereas time to relapse (TTR) focused on the subset of patients achieving CR. Death without prior progression or relapse was included as a competing risk in analyses of TTP and TTR. Post-relapse survival (PRS) was measured from the date of relapse or progression until death. For all time-to-event analyses, patients were censored at the date they were last known to be alive. Causes of death (COD) included treatment-related mortality (TRM), myeloma-related mortality (MRM), and a third category capturing other or indeterminate causes (OIM) such as fatal car accident, stroke and other causes that could not be attributed to treatment or disease. Toxicities were graded according to Version 3 of the NCI

After accrual and randomization of 289 patients, the DSMB recommended closure of the TT4-L arm due to lack of reduction in toxicity vis-à-vis TT4-S. Two patients randomized to TT4-L, were treated according to the standard arm after the DSMB recommend closure of TT4-L. These patients are accounted for in the 289 patients. Higher mortality at 1 year in patients ≥65yr on both arms (10.6% and 10.2% for TT4-L and TT4-S) prompted subsequent accrual of 74 such patients to Total Therapy 6 (TT6) designed for previously treated patients, because its less dose-intense therapies had resulted in TRM of 0% (11). Younger patients continue enrollment to TT4-S but only the 289 randomized patients are the subject of this report.

Statistical Analysis

The data set was created on January 16, 2015 on 289 patients randomized between TT4-S and TT4-L. In accordance with the intent-to-treat principle, all patients were analyzed according to their randomized arm. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the distributions of OS, PFS and CR duration (12). Cumulative incidences for COD, TTP and TTR were calculated using the method of Gooley, et al. (13). Group comparisons for survival endpoints and cumulative incidence were performed using the log-rank test (14). Multivariate models of prognostic factors were carried out using Cox regression (15). P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical Outcomes

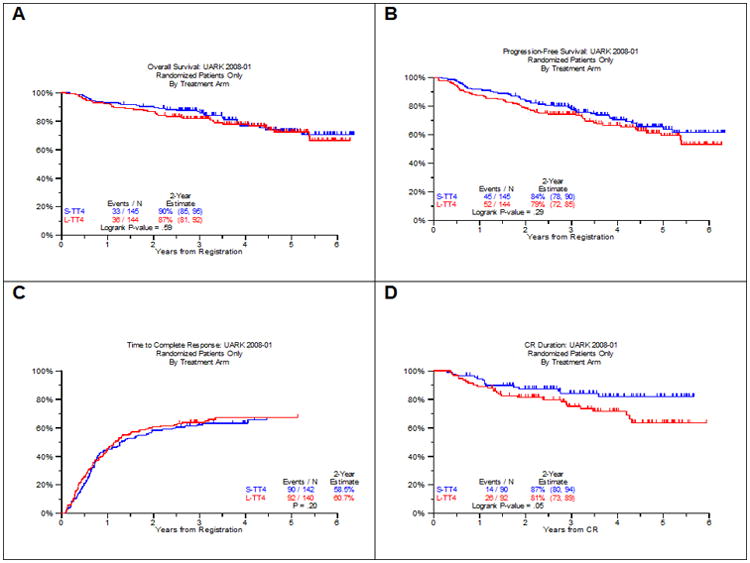

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and were not different between the 2 arms. The consort flow diagram (supplemental figure 1) portrays the progression of patients through the various protocol steps and lists the off-study reasons. Grade ≥ 3 toxicities occurred with similar frequencies in the 2 arms of TT4 (supplemental Table 2), with no significant differences observed between major toxicity categories. With a median follow-up of 4.5 years in both arms, 112 and 108 patients are alive at the time of analysis while 100 and 92 are progression-free on TT4-S and TT4-L, respectively (Figure 1). Two-year OS estimates are similar in both arms, 90% and 87% (Figure 1A); the corresponding PFS estimates of 84% and 79% were also comparable (Figure 1B). At the time of analysis, 90 and 92 had achieved CR status on TT4-S and TT4-L, respectively, for 2-yr estimates of 59% and 61% (Figure 1C); 2-year CRD estimates are 87% and 81% (P=0.05) (Figure 1D). Median TTP was similar in both arms, with 2-yr estimates of 8% and 11%, while there was a trend towards earlier TTR from CR on the TT4-L arm (12% vs 8% at 2 years, p=0.07) (data not shown). COD were divided into MRM (p=0.70), TRM (p=0.61) and OIM (p=0.25) and were not different between both arms (Supplemental Figure 2A). Post-relapse survival (PRS) was similar in the 2 arms (Supplemental Figure 2B).

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

| Factor | All Patients | S-TT4 | L-TT4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Age (yr) | 61.4 (N=289) (30.4 - 75.9) |

60.4 (N=145) (34.2 - 75.2) |

62.2 (N=144) (30.4 - 75.9) |

| Age >= 60yr | 157/289 (54%) | 74/145 (51%) | 83/144 (58%) |

| Female | 111/289 (38%) | 60/145 (41%) | 51/144 (35%) |

| IgA | 46/287 (16%) | 22/143 (15%) | 24/144 (17%) |

| IgG | 179/287 (62%) | 93/143 (65%) | 86/144 (60%) |

| ISS Stage 1 | 86/289 (30%) | 44/145 (30%) | 42/144 (29%) |

| ISS Stage 2 | 124/289 (43%) | 61/145 (42%) | 63/144 (44%) |

| ISS Stage 3 | 79/289 (27%) | 40/145 (28%) | 39/144 (27%) |

| Albumin < 3.5 g/dL | 123/289 (43%) | 58/145 (40%) | 65/144 (45%) |

| B2M >= 3.5 mg/L | 153/289 (53%) | 77/145 (53%) | 76/144 (53%) |

| B2M > 5.5 mg/L | 79/289 (27%) | 40/145 (28%) | 39/144 (27%) |

| Creatinine >= 1.5 mg/dL | 31/289 (11%) | 15/145 (10%) | 16/144 (11%) |

| Hemoglobin < 10 g/dL | 109/289 (38%) | 55/145 (38%) | 54/144 (38%) |

| Baseline PET FL > 0 | 166/261 (64%) | 82/126 (65%) | 84/135 (62%) |

| Baseline PET FL > 3 | 95/261 (36%) | 45/126 (36%) | 50/135 (37%) |

| Baseline FL-SUV > 3.9 | 79/168 (47%) | 40/84 (48%) | 39/84 (46%) |

| Cytogenetic abnormalities | 112/283 (40%) | 53/142 (37%) | 59/141 (42%) |

| amp1q21 (FISH) | 63/259 (24%) | 31/127 (24%) | 32/132 (24%) |

| delTP53 (FISH) | 19/259 (7%) | 11/127 (9%) | 8/132 (6%) |

| GEP 70 High Risk | 2/286 (1%) | 0/143 (0%) | 2/143 (1%) |

| GEP CD-1 subgroup | 16/286 (6%) | 6/143 (4%) | 10/143 (7%) |

| GEP CD-2 subgroup | 56/286 (20%) | 23/143 (16%) | 33/143 (23%) |

| GEP HY subgroup | 102/286 (36%) | 49/143 (34%) | 53/143 (37%) |

| GEP LB subgroup | 45/286 (16%) | 25/143 (17%) | 20/143 (14%) |

| GEP MF subgroup | 8/286 (3%) | 6/143 (4%) | 2/143 (1%) |

| GEP MS subgroup | 35/286 (12%) | 22/143 (15%) | 13/143 (9%) |

| GEP PR subgroup | 24/286 (8%) | 12/143 (8%) | 12/143 (8%) |

n/N (%): n- Number with factor, N- Number with valid data for factor

ND: No valid observations for factor

Bold print signifies Fisher's exact test p-value < 0.05

Figure 1. Survival Outcomes in TT4 by arm (A: OS, B: PFS, C: CR, D: CRD).

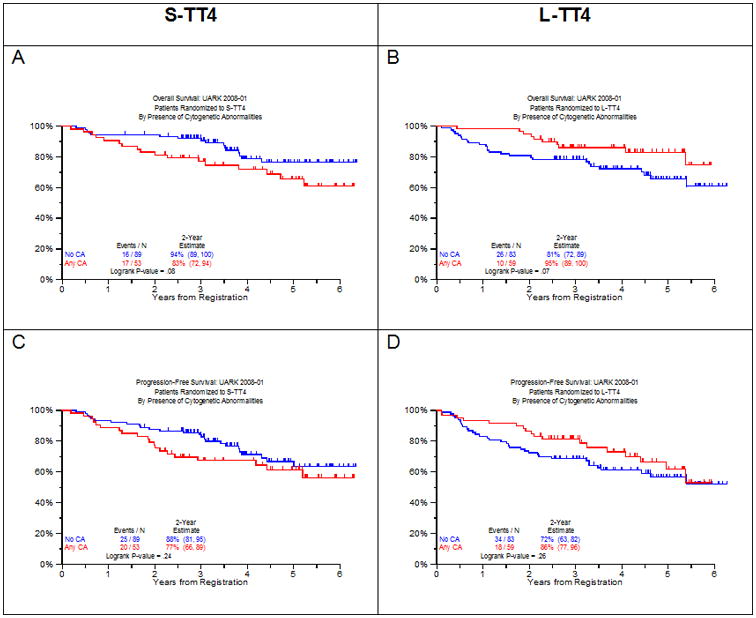

As in previous TT trials, the presence of CA affected clinical outcomes (Figure 2). Surprisingly, the presence of CA had opposite prognostic connotations in the 2 study arms. In TT4-S, CA showed a strong trend toward inferior OS (Figure 2A) while the reverse applied to TT4-L (Figure 2B). Non-significant trends in opposite directions were noted for PFS (Figure 2C, D). CRD tended to be inferior in patients with CA-type MM in TT4-S (Figure 2E) with an opposite trend in TT4-L (Figure 2F), though neither comparison was statistically significant. TTR was significantly steeper in the presence of CA in TT4-S (Figure 2G) and did not affect this outcome variable in TT4-L (Figure 2H).

Figure 2. Clinical outcomes according to the presence of cytogenetic abnormalities (no CA vs CA) by TT4 arm.

Next we examined the impact of baseline factors on outcomes (Table 2 and Table 3). The univariate cox analysis of baseline features associated with OS and PFS across TT4 arms are summarized in Table 2. OS and PFS were inferior in the case of older age ≥65yr, high beta-2-microglobulin (B2M) (both ≥3.5mg/L and >5.5mg/L), presence on PET-CT of more than 3 fluoro-deoxyglucose avid focal lesions (FL), low albumin levels (<3.5g/dL) posed a significant hazard for OS but not for PFS, and the reverse applied to CRP elevation (≥8mg/L). There was a trend for better OS and PFS for the CD1 and CD2 molecular subgroups (Table 2). In the presence of CA, in comparison to its absence (no CA), OS tended to be shorter in TT4-S (p=0.08) and longer in TT4-L (p=0.07). On multivariate analysis (Table 3), older age, B2M >5.5mg/L, and PET-FL >3 independently imparted inferior OS and PFS. Low albumin adversely affected OS and was of borderline significance for PFS. Patients with CA enjoyed superior OS when randomized to TT4-L with a strong trend apparent also for PFS. In the case of TT4-S, differences were in the opposite direction, though not significant. The different effect of CA on outcomes by treatment arm (interaction) was statistically significant for both OS and PFS (p = .0035 and .0491, respectively).

Table 2. Univariate Cox analysis of baseline features associated with overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) across TT4 arms.

| Overall Survival | Progression-Free Survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n/N (%) | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Univariate | TT4-L | 144/289 (50%) | 1.14 (0.71, 1.82) | 0.593 | 1.24 (0.83, 1.85) | 0.290 |

| Age >= 65 yr | 96/289 (33%) | 2.27 (1.41, 3.64) | <.001 | 1.89 (1.26, 2.82) | 0.002 | |

| Albumin < 3.5 g/dL | 132/289 (46%) | 1.90 (1.17, 3.08) | 0.010 | 1.43 (0.96, 2.14) | 0.077 | |

| B2M >= 3.5 mg/L | 153/289 (53%) | 2.40 (1.44, 4.01) | <.001 | 1.79 (1.18, 2.70) | 0.006 | |

| B2M > 5.5 mg/L | 79/289 (27%) | 1.93 (1.18, 3.14) | 0.009 | 1.88 (1.24, 2.85) | 0.003 | |

| Creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL | 31/289 (11%) | 1.30 (0.65, 2.62) | 0.461 | 1.70 (0.98, 2.94) | 0.060 | |

| CRP >= 8 mg/L | 80/288 (28%) | 1.60 (0.98, 2.61) | 0.058 | 1.56 (1.03, 2.36) | 0.037 | |

| Hb < 10 g/dL | 109/289 (38%) | 1.42 (0.88, 2.28) | 0.151 | 1.31 (0.87, 1.96) | 0.193 | |

| Baseline PET FL > 0 | 166/261 (64%) | 1.49 (0.86, 2.57) | 0.153 | 1.35 (0.86, 2.12) | 0.187 | |

| Baseline PET FL > 3 | 95/261 (36%) | 2.72 (1.63, 4.52) | <.001 | 2.13 (1.40, 3.26) | <.001 | |

| GEP CD-1 subgroup | 16/285 (6%) | 0.22 (0.03, 1.57) | 0.131 | 0.30 (0.07, 1.21) | 0.090 | |

| GEP CD-2 subgroup | 56/285 (20%) | 1.47 (0.85, 2.54) | 0.171 | 1.49 (0.94, 2.37) | 0.090 | |

| GEP HY subgroup | 102/285 (36%) | 0.84 (0.50, 1.39) | 0.489 | 0.74 (0.48, 1.14) | 0.175 | |

| GEP LB subgroup | 44/285 (15%) | 1.26 (0.69, 2.30) | 0.454 | 1.47 (0.90, 2.40) | 0.126 | |

| GEP MF subgroup | 8/285 (3%) | 1.13 (0.28, 4.61) | 0.867 | 1.12 (0.35, 3.53) | 0.853 | |

| GEP MS subgroup | 35/285 (12%) | 0.75 (0.34, 1.64) | 0.470 | 0.69 (0.34, 1.36) | 0.280 | |

| GEP PR subgroup | 24/285 (8%) | 1.25 (0.57, 2.72) | 0.583 | 1.33 (0.69, 2.56) | 0.393 | |

| TT4-S only | Any CA vs No CA | 53/142 (37%) | 1.84 (0.93, 3.64) | 0.081 | 1.42 (0.79, 2.56) | 0.244 |

| TT4-L only | Any CA vs No CA | 59/142 (42%) | 0.51 (0.25, 1.07) | 0.074 | 0.71 (0.40, 1.26) | 0.248 |

HR- Hazard Ratio, 95% CI- 95% Confidence Interval, P-value from Wald Chi-Square Test in Cox Regression

NS2- Multivariate results not statistically significant at 0.05 level. All univariate p-values reported regardless of significance

Multivariate model uses stepwise selection with entry level 0.1 and variable remains if meets the 0.05 level.

A multivariate p-value greater than 0.05 indicates variable forced into model with significant variables chosen using stepwise selection

Table 3. Multivariate Cox regression analysis of baseline features associated with overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) across TT4 arms.

| Overall Survival | Progression-Free Survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n/N (%) | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Multivariate | Age >= 65 yr | 86/257 (33%) | 2.01 (1.19, 3.38) | 0.0086 | 1.76 (1.14, 2.72) | 0.0110 |

| Albumin < 3.5 g/dL | 118/257 (46%) | 1.90 (1.12, 3.20) | 0.0167 | 1.46 (0.95, 2.24) | 0.0838 | |

| B2M > 5.5 mg/L | 67/257 (26%) | 2.40 (1.35, 4.29) | 0.0030 | 2.08 (1.30, 3.35) | 0.0024 | |

| Baseline PET FL > 3 | 93/257 (36%) | 2.94 (1.73, 5.01) | <.0001 | 2.24 (1.44, 3.49) | 0.0003 | |

| Any CA vs No CA (TT4-L) * | 58/133 (44%) | 0.36 (0.16, 0.79) | 0.0113 | 0.56 (0.30, 1.05) | 0.0698 | |

| Any CA vs No CA (TT4-S) * | 50/124 (40%) | 1.73 (0.81, 3.71) | 0.1575 | 1.35 (0.71, 2.56) | 0.3565 | |

HR- Hazard Ratio, 95% CI- 95% Confidence Interval, P-value from Wald Chi-Square Test in Cox Regression

P-value for the CA by Treatment arm interactions, OS: p = 0.0035; PFS: p = 0.0491

Denominators represent the total number of patients relevant to this hazard ratio rather than the total number of patients in the model.

As we had previously reported on prognostic implication of imaging parameters, we sought to determine whether the adverse clinical impact of PET-FL>3 pertained to both TT4 arms (16). Regardless of treatment arm, OS and PFS were inferior for PET-FL >3 (Supplementary Figure 3). The timing of onset of CR was not affected by PET-FL, while CRD was superior in case of PET-FL =<3 for the TT4-S arm but not for TT4-L. A trend for more rapid TTP with PET-FL >3 was observed in TT4-S whereas TTP was similar in TT4-L. TTR was significantly faster with PET-FL >3 only in case of TT4-S.

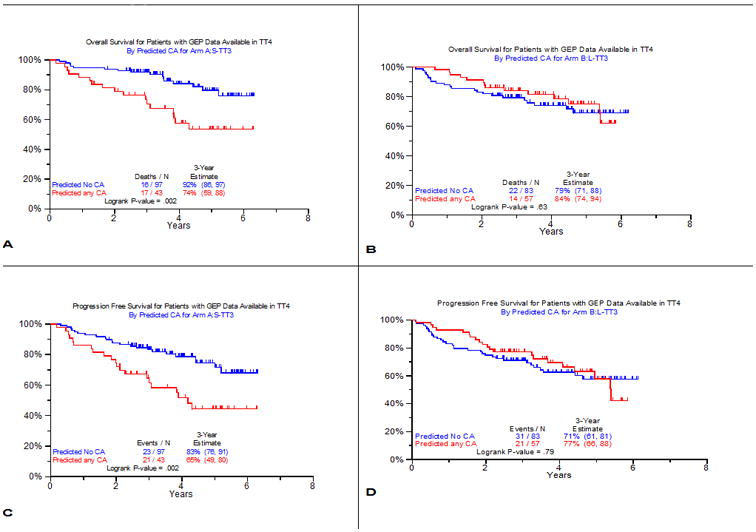

GEP probes linked to the presence of cytogenetic abnormalities (CA)

The observation of CA's favorable OS impact in TT4-L was unexpected and at variance with findings in all previous TT protocols (17). We therefore analyzed whether the presence or absence of metaphase CA could be linked to certain gene probes which might explain the superior performance in TT4-L of fractionated melphalan with added bortezomib and thalidomide. A training set of patients with LR-MM enrolled in TT3a was chosen for this endeavor. Among 266 untreated patients with available baseline GEP studies, 90 (34%) exhibited CA. Among the test set of 164 patients with baseline GEP accrued to TT3b, 67 (41%) qualified as having CA. Using a false discovery rate of 0.0001, 51 probes significantly distinguished patients with and without CA (Supplementary Table 3). Seven of the 51 genes function in DNA replication, recombination, and repair; five in nucleic acid metabolism, and 4 in RNA post-translational modification and RNA damage and repair. Ingenuity pathway analysis identified a network of eight interrelated genes that were overexpressed in the CA group, indicating that these MM cells have a higher proliferative activity (Supplementary Figure 4). We then examined clinical outcomes by the GEP51-CA prediction model in the 2 arms of TT4 (Figure 3). In TT4-S, GEP51/no-CA had superior OS and PFS compared to GEP51/CA (Figure 3A, B), which was not observed in TT4-L (Figure 3C, D).

Figure 3. Clinical outcomes according to 51-gene model predicting CA versus no-CA.

Discussion

The results of this phase-3 TT4 trial failed to show that TT4-L was less toxic and was, in fact, inferior to TT4-S in terms of CRD with a trend for inferiority in case of TTR. One-year mortality was similar, 7.6% in TT4-L and 6.9% in TT4-S (Fisher's Exact Test p=0.75), but low in both arms in younger patients (TT4-S, 6.2%; TT4-L, 5.2%). Unanticipated were the opposite implications of the presence of CA on OS: adverse in TT4-S (p=0.08) as in all previous TT trials, and favorable in TT4-L (p=0.07), with significant opposite prognostic implications in the 2 study arms. The other clinical endpoints were only marginally affected except for significantly faster TTR in case of CA in TT4-S. When analyzed in the context of all competing variables, TT4-L impacted OS of patients with CA-type MM favorably, with a strong trend apparent also for PFS. T It seems reasonable to speculate that CA-type MM derived benefit from conditioning with fractionated MEL VTD since T4-L employed 1 less cycle of induction and consolidation treatment. This combination has also been found to be synergistic when used to treat patients with VMP ineligible for stem cell transplantation in the VISTA study (18).

We previously reported that bortezomib and VTD could be added to fractionated EL in doses up to 250mg/m2 in an advanced patient population with acceptable toxicity and high response rates (7, 8). Others have also explored the use of bortezomib and MEL as a conditioning regimen prior to transplantation and found that both agents can be safely combined and possibly produce increased response rates (19-22). The present paper is the first randomized study comparing single dose melphalan 200mg/m2 with a fractionated MELVTD schedule. The results of TT4 indicate that CA-type myeloma benefits from MELVTD, whilst non-CA MM fares better with application of a single high dose MEL 200mg/m2. Prior attempts to improve conditioning with MEL have not been successful and included the addition of other drugs, skeletal targeting radioactive antibodies or radiation therapy (23-28).

Mono- or poly ubiquination of DNA-repair enzymes such H2AX, BRCA1, and FANCD2 is required for recruitment to sites of DNA double stranded breaks and is essential to the DNA damage response (29). Bortezomib reduces the availability of nuclear ubiquitin and may thereby impair homologous recombination mediated DNA-repair. It has been suggested that bortezomib renders myeloma cells more vulnerable to alkylator-mediated DNA-damage by essentially inducing a BRCAness type state (30). CA-type MM is likely to harbor more genomic chaos and may be more dependent on efficient DNA-repair explaining the sensitivity to fractionated MEL-VTD conditioning. Availability of GEP led us to examine whether CA-linked gene probes could be identified. Indeed 51 genes were identified that distinguished no-CA from CA subgroups. When examined for its clinical relevance, the GEP51 model was prognostic in TT4-S so that GEP51/CA prediction was associated with inferior OS and PFS. In contrast, such Kaplan-Meier plots were superimposable between these 2 groups in TT4-L. Ingenuity pathway analysis suggests that CA-type MM has overexpression of genes critical to proliferation. The ability to examine metaphase cytogenetics inherently implies that the myeloma cells are able to survive and proliferate in vitro without the support of the myeloma micro-environment. Increased ability to proliferate may be a favorable evolutionary trait, but on the other hand stress requirements for DNA-repair to prevent fatal mutations and cell death. In this context, one could speculate that exposure to DNA-damaging alkylators such as MEL in the setting of bortezomib-induced reduced DNA-repair could lead to fatal “mitotic catastrophes”.

This is the first clinical trial, which suggests that tailoring the transplant conditioning regimen to myeloma biology may further improve outcome. However, the study was not designed to specifically study the impact of conditioning on outcome in the context of metaphase CA. These preliminary findings therefore require confirmation in future phase III studies.

Supplementary Material

Key Point.

Conditioning with melphalan, bortezomib and thalidomide confers benefit to myeloma with abnormal metaphase cytogenetics.

Translational Relevance.

Melphalan 200mg/m2 is widely considered the standard preparatory regimenfor autologous stem cell transplantation for myeloma. Attempts to improve conditioning with melphalan have not been successful and included the addition of other cytotoxic agents, skeletal targeting radioactive antibodies or radiation therapy. The present study suggests that patients with abnormal metaphase cytogenetics, who traditionally fare worse than their counterparts with normal metaphase cytogenetics, may benefit from the addition of bortezomib, thalidomide and dexamethasone to a fractionated melphalan (50mg/m2/d × 4d) conditioning regimen. Conversely, patients with a normal karyotype are best served with preparation comprising melphalan 200mg/m2 given in a single dose. These findings, if confirmed suggest that specific autologous stem cell transplantation conditioning regimens can improve outcome in subgroups of myeloma patients.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Total Therapy 4 was supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health Program Project Grant CA55819 (to Dr. Gareth Morgan).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: There are no relevant conflicts to disclose.

Author Contributions: FvR, AH, JC and BB designed the research. JE, MZ, SY, ET, SW, RK, YJ, XP, MG, NP, DS, SP, CB, MCF, FvR and BB performed the research. FvR, AM, AH, JC and BB analyzed the data. FvR, AM, JC, BB and GM wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Barlogie B, Tricot G, Anaissie E, Shaughnessy JD, Jr, Rasmussen E, van Rhee F, et al. Thalidomide and hematopoietic-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1021–1030. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barlogie B, Anaissie E, van Rhee F, Haessler J, Hollmig K, Pineda-Roman M, et al. Incorporating bortezomib into upfront treatment for multiple myeloma: Early results of Total Therapy 3. Br J Haematol. 2007;138:176–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaughnessy JD, Jr, Zhan F, Burington BE, Huang Y, Colla S, Hanamura I, et al. A validated gene expression model of high-risk multiple myeloma is defined by deregulated expression of genes mapping to chromosome 1. Blood. 2007;109:2276–2284. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-038430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barlogie B, Mitchell A, van Rhee F, Epstein J, Morgan GJ, Crowley J. Curing myeloma at last: Defining criteria and providing the evidence. Blood. 2014;124:3043–3051. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-552059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaughnessy JD, Jr, Qu P, Usmani S, Heuck CJ, Zhang Q, Zhou Y, et al. Pharmacogenomics of bortezomib test-dosing identifies hyperexpression of proteasome genes, especially PSMD4, as novel high-risk feature in myeloma treated with Total Therapy 3. Blood. 2011;118:3512–3524. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-328252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nair B, van Rhee F, Shaughnessy JD, Jr, Anaissie E, Szymonifka J, Hoering A, et al. Superior results of Total Therapy 3 (2003-33) in gene expression profiling-defined low-risk multiple myeloma confirmed in subsequent trial 2006-66 with VRD maintenance. Blood. 2010;115:4168–4173. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-255620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hollmig K, Stover J, Talamo G, Zangari M, Thertulien R, van Rhee F, et al. Addition of bortezomib (Velcade™) to high dose melphalan (Vel-Mel) as an effective conditioning regimen with autologous stem cell support in multiple myeloma (MM) Blood. 2004;104:929. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pineda-Roman M, Cottler-Fox M, Hollmig K, Anaissie EJ, van Rhee F, Tricot G, et al. Retrospective analysis of fractionated high-dose melphalan (F-Mel) and bortezomib-thalidomide-dexamethasone (VTD) with autotransplant (AT) support for advanced and refractory multiple myeloma (AR-MM) Blood. 2006;108:3102. [Google Scholar]

- 9.International Myeloma Working Group. Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: A report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:749–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durie BG, Harousseau JL, Miguel JS, Bladé J, Barlogie B, Anderson K, et al. International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2006;20:1467–1473. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Rhee F, Giralt S, Barlogie B. The future of autologous stem cell transplantation in myeloma. Blood. 2014;124:328–333. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-561985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J AM Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: New representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18:695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mantel N. Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waheed S, Mitchell A, Usmani S, Epstein J, Yaccoby S, Nair B, et al. Standard and novel imaging methods for multiple myeloma: correlates with prognostic laboratory variables including gene expression profiling data. Haematologica. 2013;98:71–8. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.066555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arzoumanian V, Hoering A, Sawyer J, van Rhee F, Bailey C, Gurley J, et al. Suppression of abnormal karyotype predicts superior survival in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2008;22:850–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.San Miguel JF, Schlag R, Khuageva NK, Dimopoulos MA, Shpilberg O, Kropff M, et al. Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone for initial treatment of multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:906–917. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roussel M, Moreau P, Huynh A, Mary JY, Danho C, Caillot D, et al. Bortezomib and high-dose melphalan as conditioning regimen before autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with de novo multiple myeloma: A phase 2 study of the Intergroupe Francophone du Myelome (IFM) Blood. 2010;115:32–37. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-229658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lonial S, Kaufman J, Tighiouart M, Nooka A, Langston AA, Heffner LT, et al. A phase I/II trial combining high-dose melphalan and autologous transplant with bortezomib for multiple myeloma: A dose- and schedule-finding study. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5079–5086. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson PA, Prince HM, Seymour JF, Ritchie D, Stokes K, Burbury K, et al. Bortezomib added to high-dose melphalan as pre-transplant conditioning is safe in patients with heavily pre-treated multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46:764–765. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SR, Kim SJ, Park Y, Sung HJ, Choi CW, Kim BS, et al. Bortezomib and melphalan as a conditioning regimen for autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma. Korean J Hematol. 2010;45:183–187. doi: 10.5045/kjh.2010.45.3.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimoni A, Smith TL, Aleman A, Weber D, Dimopoulos M, Anderlini P, et al. Thiotepa, busulfan, cyclophosphamide (TBC) and autologous hematopoietic transplantation: An intensive regimen for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27:821–828. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anagnostopoulos A, Aleman A, Ayers G, Donato M, Champlin R, Weber D, et al. Comparison of high-dose melphalan with a more intensive regimen of thiotepa, busulfan, and cyclophosphamide for patients with multiple myeloma. Cancer. 2004;100:2607–2612. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christoforidou AV, Saliba RM, Williams P, Qazilbash M, Roden L, Aleman A, et al. Results of a retrospective single institution analysis of targeted skeletal radiotherapy with (166) holmium-DOTMP as conditioning regimen for autologous stem cell transplant for patients with multiple myeloma. Impact on transplant outcomes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.12.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giralt S, Bensinger W, Goodman M, Posoloff D, Eary J, Wendt R, et al. 166ho-DOTMP plus melphalan followed by peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma: Results of two phase 1/2 trials. Blood. 2003;102:2684–2691. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desikan KR, Tricot G, Dhodapkar M, Fassas A, Siegel D, Vesole DH, et al. Melphalan plus total body irradiation (MEL-TBI) or cyclophosphamide (MEL-CY) as a conditioning regimen with second autotransplant in responding patients with myeloma is inferior compared to historical controls receiving tandem transplants with melphalan alone. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25:483–487. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreau P, Facon T, Attal M, Hulin C, Michallet M, Maloisel F, et al. Comparison of 200 mg/m(2) melphalan and 8 Gy total body irradiation plus 140 mg/m(2) melphalan as conditioning regimens for peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: Final analysis of the Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome 9502 randomized trial. Blood. 2002;99:731–735. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neri P, Ren L, Gratton K, Stebner E, Johnson J, Klimowicz A, et al. Bortezomib-induced “BRCAness” sensitizes multiple myeloma cells to PARP inhibitors. Blood. 2011;118:6368–6379. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-363911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fonseca R. Innovation in myeloma treatments PARP excellence! Blood. 2011;118:6234–6235. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-381129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.