Abstract

In the Navajo language, the word for cancer translates as the sore that does not heal. This literal linkage to a sense of hopelessness reflects a cultural perspective that impedes cancer detection in its early, more treatable stages. As a coauthor of this article and a Navajo breast cancer survivor, Nellie Sandoval, BS, MS, explains that the very topic of cancer is taboo to discuss among the Navajo population, for to speak of cancer is to invite it. When statistical data from the San Juan Regional Tumor Registry supported the authors’ anecdotal findings regarding late diagnoses, they created Breast Cancer: It Can Be Healed. The first Navajo-language video to address such cultural barriers, it discusses the triad of early detection—breast self-examination, clinical examination, and mammography. Its success sparked creation of a second video, sponsored by the Native American Cancer Research Partnership (NACRP). The 12-minute video, Breast Cancer: The Healing Begins, focuses on treatment options, including surgery, radiation, and hormone therapy. By conducting field screenings throughout the Navajo Nation, the NACRP team has enhanced the video’s visual imagery and messages and has confirmed the value of cultural relevancy in cancer education.

Although death rates from female breast cancer declined overall from 1992–2000 for white, Hispanic, and African American women, rates for Native Americans and Alaska Natives remained constant (American Cancer Society, 2004). Investigators exploring reasons for the lack of improvement in survival rates for the latter two populations cite cultural dynamics and differences as key contributors (Carrese & Rhodes, 2000; Giuliano, Papenfuss, de Guernsey de Zapien, Tilousi, & Nuvayestewa, 1998).

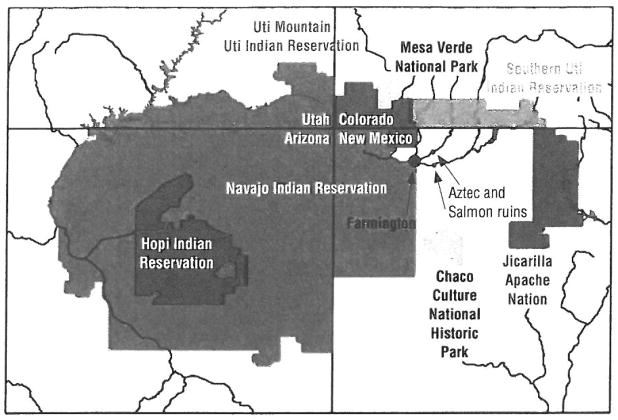

The Four Corners region of the United States, where the states of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah meet, is home to about 125,000 Native Americans (see Figure 1). The Navajo Nation, located in the Four Corners region, is the largest Native American population in the United States. It has the largest number of native speakers whose native language is their primary language. A collaborative effort to reduce cultural contributors to breast cancer deaths now is approaching the decade mark. Using original video presentations in the Navajo language, a team of health professionals, researchers, and educators from New Mexico and Arizona are proving that culturally relevant educational materials can alter attitudes and impact behaviors supportive to early detection, intervention, and outcomes.

Figure 1. Map of the Four Corners, Location of the Navajo Nation.

Note. The Navajo Nation is the largest Native American population in the United States. Navajo Nation lands cover an area approximately the size of West Virginia.

Identifying a Need

The catalyst for the project collaboration was author Nellie Sandoval’s diagnosis of breast cancer in 1989. Author Frances Robinson, RN, OCN®, was her oncology nurse.

A high school counselor, Sandoval, BS, MS, communicated her concerns that other Navajo women were dying of breast cancer because, in large part, of lack of medical education about the treatment of cancer. In the Navajo language, cancer translates as the sore that does not heal. Literally and symbolically, such words speak to a cultural perspective that impedes cancer detection in its early, more treatable stages. The very topic of cancer has been taboo among the population, for to discuss cancer is to invite it.

Although the incidence of breast cancer among Navajo women is no greater than their non-Native peers (Hispanic white, non-Hispanic white, African American, and Asian Pacific Islander women), their five-year survival rate is among the poorest of all ethnic groups in New Mexico (Herman, 2000), as shown in Table 1. Tumor registry reports reinforced, too, that Native American women confirmed to have breast cancer are more likely than their counterparts to have lymph node involvement or metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis (University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, 2004).

Table 1.

Breast Cancer: Five-Year Relative Survival by Race and Ethnicity, New Mexico 1997–2002

| Race and Ethnicity | % |

|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic white | 99.7 |

| Hispanic white | 95.3 |

| Native American | 91.5 |

| African American | 81.2 |

| Non-Native Americana | 98.5 |

Includes white (Hispanic and non-Hispanic), African American, and Asian Pacific Islander

Note. Based on information from National Cancer Institute, n.d.; Weir et al., 2003.

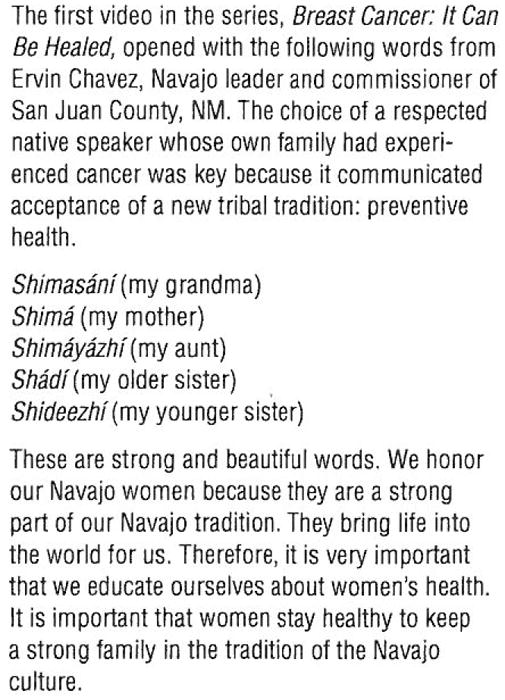

Robinson and Sandoval determined that a clinically accurate video voiced by a Native American—one that delivered a clear message along with a much-needed message of permission—was the most direct and cost-effective communication channel (see Figure 2). With financial support from the San Juan Medical Foundation, they produced Breast Cancer: It Can Be Healed, a nine-minute video, in 1998. It was the first Navajo-language presentation to discuss the triad of early detection—breast self-examination, clinical examination, and mammography—and has been viewed by audiences in 12 states, from Arizona to Alaska. In addition to educating directly and opening much-needed discussion, the video has become a catalyst in its own right, inspiring others to create parallel presentations for non-Navajo Native American populations.

Figure 2.

Opening Words of Breast Cancer: It Can Be Healed

National Outreach With a Navajo Focus

By 2004, the success of the first video had sparked creation of a second. The objective of the second was to communicate breast cancer treatment modalities—surgery, radiation, and hormone therapy.

Once again, Robinson and Sandoval developed the preliminary script. They then worked with Margaret Whalawitsa, health promotions specialist in the Health Promotions Department at Northern Navajo Medical Center and a respected health educator for the Navajo Nation, to create the proper cultural context for the presentation of clinical information. Other Navajo health educators helped brainstorm visual components of the video, and language experts guided phrasing and delivery.

The intent was to generate a sense of ownership among all participants, to develop a healing community as they developed the communications.

Funding for Breast Cancer: The Healing Begins was secured as part of the outreach component of the Native American Cancer Research Partnership (NACRP). The NACRP is a cooperative agreement funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and jointly administered by Northern Arizona University and the Arizona Cancer Center. The partnership’s mission is “to address the unequal burden of cancer in Native Americans by fostering programs that increase training and educational opportunities for Native American students, faculty, and community members interested in pursuing careers in cancer research and oncology-related health care” (University of Arizona, 2005).

Field Testing for Relevance

In June 2003, Robinson and Sandoval launched a preliminary evaluation of the pilot video. Their goal was to use an NCI video evaluation survey to clarify subject matter, identify areas of cultural sensitivity, and pinpoint the perceived value of the presentation. The two traveled to multiple sites throughout the Navajo Nation during a six-month period, showing the video to more than 100 individuals. More than 90% of viewers were Native American healthcare providers.

Of those who viewed the video, 97 provided feedback. Response was generally positive (see Table 2 and Figure 3); 100% of viewers said they received information they needed. However, several valuable suggestions for improvement were offered. Key criticisms included the need for greater patient empowerment (“Let the woman express her feelings more.”) and more personal detail (“Have the patient explain her experiences before and after the diagnosis.”). The response to the cultural appropriateness of the video was strongly positive.

Table 2.

Results of the Evaluation

| Did the video help you | Yes (%) |

|---|---|

| Get the information you needed? | 100 |

| Understand more about treatment? | 100 |

| Understand more about chemotherapy? | 96 |

| Understand more about radiation therapy? | 97 |

| Understand more about hormone therapy? | 97 |

| Inform you about support groups? | 98 |

| Feel more in control of your health care? | 93 |

N = 97

Figure 3.

Comments From Viewers

The formative evaluation guided revisions to the video and helped establish an approach for future evaluation. Decisions were made to

Partner with four New Mexico healthcare centers serving Navajo women: Northern Navajo Medical Center in Shiprock, San Juan Regional Medical Center in Farmington, San Juan Surgical Associates, and San Juan Oncology Associates.

Conduct knowledge and attitudinal surveys with patients and providers after they viewed the video.

Interview patients and providers six months later to elucidate factors that may have assisted women through the treatment process.

By pursuing this approach, the team hoped to gain insight into communication patterns of providers and patients during the course of treatment, as well as ways in which families, communities, support groups, and traditional Navajo medicine prove to be of assistance.

In June 2004, the NACRP team sought approval for a two-year evaluation of the revised video. The project established collaboration with Northern Navajo Medical Center, San Juan Regional Medical Center, San Juan Oncology Associates, San Juan Regional Cancer Center, and San Juan Surgical Associates.

The NACRP and its collaborators are recruiting 30 Navajo women diagnosed with breast cancer (primary participants) and 20 healthcare providers (secondary participants) to take part in an active evaluation of the second video. Primary participants will view the video and answer 16 knowledge-based questions. They will be interviewed six months later to further elucidate factors that may have impacted women’s treatment decisions, follow-through with recommended treatment, and outcomes. Findings will reflect the impact of the video. The same protocol will be used for provider participants.

The Practical Benefits of Partnership

The team believes that the video will benefit Navajo women by increasing their understanding of breast cancer treatment options, decreasing fears about treatment, increasing communication with healthcare providers, and increasing overall health status. The long-term goal of the project, as well as other education efforts of the Navajo Nation, is to improve the breast cancer survival rates of Navajo women (Baur, Englert, Michalek, Canfield, & Mahoney, 2005; Burhansstipanov, 2005; Weiner, Burhansstipanov, Krebs, & Restivo, 2005).

Healthcare providers will benefit from improved communication with their patients and from having a practical tool for helping women make informed decisions. As part of her work on the video process, Navajo health educator Margaret Whalawitsa developed a consent form on CD-ROM to reinforce the printed consent form. Thus, bilingual participants can read and hear details of the document.

For the university and the community at large, the project offers several benefits. One of the goals of the NACRP is to create learning centers where university students and faculty can work closely with healthcare providers and community members on joint projects. A common challenge for universities is to foster the development of practical reasoning in students so that they can participate effectively in such projects. Understanding a problem in the context of a particular community and matching an intervention with local norms and practices are critical.

Fostering the development of practical reasoning requires student immersion, which deepens sensitivity to the complexities of a local situation. The project plans to directly involve Navajo students in the evaluation of the video, with the hope of building a cadre of Navajo healthcare professionals and researchers who will return to work in and serve their local Native communities. Healthcare practitioners and community members, in turn, reap the benefits of learning from their university partners about evaluation methods and research skills.

At the conclusion of the two-year project, the NACRP will submit an executive report of its findings to the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board. Upon approval to disseminate the findings, the executive report will be sent to participating patients and providers, collaborators, community health representatives, and the Navajo Nation Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention Project.

Any requests for technical assistance or dissemination activities will be honored to the extent possible. The video will be disseminated to healthcare professionals serving the Navajo Nation at no charge with an accompanying brochure.

Respect, Research, and Relevance

The most recent figures available show the breast cancer five-year survival rate for Native American women in New Mexico to be more than 8% below that of their white counterparts (see Table 1). Early diagnosis and intervention are major contributors to the disparity.

The collective goal of all involved in the effort described in this article is to harness the power of culturally sensitive education to close the gap. Seeing accurate treatment depictions in a safe environment and hearing facts in one’s own language can dramatically reduce fear and encourage compliance.

By conducting an initial pilot evaluation, revising the content and approach of the video, and evaluating the impact of the completed video, the NACRP team hopes to enhance the reach and impact of Breast Cancer: The Healing Begins and confirm the value of cultural relevancy in cancer education.

Native American women have the lowest rate of breast cancer incidence but also have some of the poorest five-year survival rates of all ethnic groups in New Mexico

Historically, cultural issues and sensitivities among Native American populations have impeded the early detection and effective treatment of breast cancer

The Navajo Nation is the largest Native American population in the United States. It also has the largest number of native speakers whose native language is their first language. The geographic home of the Navajo Nation includes some of the country's most remote regions, making access a key communications barrier.

By developing comprehensive, culturally relevant communications to open dialogue and deliver facts regarding breast cancer detection and treatment options, awareness is enhanced and outcomes are improved.

Validating content and delivery—including subtle nuances of language and imagery—with the primary audience enhances receptivity and legitimacy of the message.

Acknowledgments

The project on which this article is based was funded by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (#U54CAO96320-03).

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the Navajo Nation; Judy C. Kneece, RN, OCN®, of EduCare, Inc.; Nicolette Teufel-Shone, PhD, of the Health Promotion Sciences program in the College of Public Health at the University of Arizona; Harriett Hosetosavit, MPH, of the White River Apache Tribe, NACRP, Northern Arizona University; Margaret Whalawitsa, health promotions specialist in the Health Promotions Department at Northern Navajo Medical Center; the San Juan Medical Foundation; and the many other friends and supporters of this project.

References

- American Cancer Society. Breast cancer facts and figures 2003–2004. Atlanta, GA: Author; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Baur JE, Englert JJ, Michalek AM, Canfield P, Mahoney MC. American Indian cancer survivors: Exploring social network topogy and perceived social supports. Journal of Cancer Education. 2005;20(Suppl):23–27. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2001s_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burhansstipanov L. Community driven Native American cancer survivors’ quality of life research priorities. Journal of Cancer Education. 2005;20(Suppl):7–11. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2001s_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrese JA, Rhodes LA. Bridging cultural differences in medical practice. The case of discussing negative information with Navajo patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15:92–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.03399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano A, Papenfuss M, de Guernsey de Zapien J, Tilousi S, Nuvayestewa L. Breast cancer screening among southwest American Indian women living on-reservation. Preventive Medicine. 1998;27:135–143. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman CJ. Breast cancer in New Mexico. Santa Fe, NM: New Mexico Department of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer of the breast. n.d Retrieved November 3,2005, from http://www.seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html.

- University of Arizona. Departmental Web accounts. 2005 Retrieved November 3, 2005, from http://narcp.web.arizona.edu/

- University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center. New Mexico tumor registry. Retrieved November 3, 2005, from http:/hsc.unm.edu/epiccpro/

- Weiner D, Burhansstipanov L, Krebs LU, Restivo T. From survivorship to thrivership: Native people weaving a healthy life from cancer. Journal of Cancer Education. 2005;20(Suppl):28–32. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2001s_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir HK, Thun MJ, Hankey BF, Ries LAG, Howe HL, Wingo PA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2000, featuring the uses of surveillance data for cancer prevention and control. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2003;95:1276–1299. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg040. Retrieved November 3, 2005, from http://jncicancerspectrum.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/jnci%3b95/17/1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]