Abstract

BACKGROUND: CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) tumors, comprising 20% of colorectal cancers, are associated with female sex, age, right-sided location, and BRAF mutations. However, other factors potentially associated with CIMP have not been robustly examined. This meta-analysis provides a comprehensive assessment of the clinical, pathologic, and molecular characteristics that define CIMP tumors. METHODS: We conducted a comprehensive search of the literature from January 1999 through April 2018 and identified 122 articles, on which comprehensive data abstraction was performed on the clinical, pathologic, molecular, and mutational characteristics of CIMP subgroups, classified based on the extent of DNA methylation of tumor suppressor genes assessed using a variety of laboratory methods. Associations of CIMP with outcome parameters were estimated using pooled odds ratio or standardized mean differences using random-effects model. RESULTS: We confirmed prior associations including female sex, older age, right-sided tumor location, poor differentiation, and microsatellite instability. In addition to the recognized association with BRAF mutations, CIMP was also associated with PIK3CA mutations and lack of mutations in KRAS and TP53. Evidence of an activated immune response was seen with high rates of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (but not peritumoral lymphocytes), Crohn-like infiltrates, and infiltration with Fusobacterium nucleatum bacteria. Additionally, CIMP tumors were associated with advance T-stage and presence of perineural and lymphovascular invasion. CONCLUSION: The meta-analysis highlights key features distinguishing CIMP in colorectal cancer, including molecular characteristics of an active immune response. Improved understanding of this unique molecular subtype of colorectal cancer may provide insights into prevention and treatment.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major public health problem as more than 1 million new cases are diagnosed worldwide every year [1]. CRCs represent a heterogeneous group of tumors characterized by complex multifactorial phenotypes that are influenced by host factors [2]. These include diet, environmental, microbial, genetic, and epigenetic factors, as well as metabolic and other exposures [3]. In addition, genomic instability is an important molecular event in the development of CRC, encompassing chromosomal instability, microsatellite instability (MSI), and aberrant DNA methylation [4]. Two main pathways have been characterized in the development of CRC. The suppressor pathway is involved in 80% of CRC cases and is characterized by chromosomal instability. The remaining 15%-20% of CRCs likely arise from the serrated adenoma pathway, which is often associated with epigenetic silencing of the mismatch repair gene MLH1. Aberrant DNA methylation is a hallmark of human cancer and consists of both global DNA hypomethylation and site-specific DNA hypermethylation [5], [6]. CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP), thought to be a precursor to the serrated adenoma pathway, represents a subset of CRCs characterized by significant hypermethylation of CpG islands of tumor suppressor genes, leading to their inactivation and thereby promoting tumor progression [6], [7]. CIMP is a distinct phenotype characterized by high promoter methylation of several genes including MINT clones, p16, THBS, and MLH1 as first shown by Toyata et al. in CRC tissues and is characterized by key clinical, pathologic, and molecular characteristics, including female sex, old age, high MSI, BRAF mutations, and right-sided tumor location [7], [8].

Since the discovery of CIMP in 1999, various tools and methodologies have been developed to quantify methylation and CIMP status in CRC tumors. The first panel used MINT or specific methylated in tumor markers to study gene-specific methylation [7]. Subsequently, the Weissenberg panel and Ogino panel were developed and are widely used to study CIMP among CRC patients [9]. In 2016, a systematic review of the clinical, pathologic, and molecular characteristics of CIMP tumors showed that CIMP was associated with BRAF mutations, high MSI, female sex, right-sided tumor location, and age [8]. The researchers classified CIMP identification methodologies into four groups: Classical panel, Weisenberg panel, Combination panels, and Human Methylation Arrays. Using these classifications, the researchers found that the association of CIMP with the various clinical, pathologic, and molecular characteristics differed in magnitude and direction of association based on methodological classification [8]. However, their study restricted their inclusion to these methodological subtypes.

With advancement in technology and better understanding of epigenetic basis of disease, classification of CIMP varies based on definition and methodology, and is generally classified as CIMP-High (CIMP-H), CIMP-Low (CIMP-L) and CIMP-0, or CIMP-Positive and CIMP-Negative [10]. However previous studies have also reported no differences in CIMP-L and CIMP-0, and classified them as non-CIMP or CIMP-0 [9], [11]. With the growing influence of translational research and molecular pathology, integrating molecular, lifestyle, and demographic characteristics is key to understanding the carcinogenic pathways that underlie different subtypes of cancer. This systematic review aims to provide an update to the previous literature with a comprehensive assessment of the clinical, pathologic, and molecular characteristics of CIMP tumors in CRC. In addition, we have performed a meta-analysis of all factors with adequate available data to clarify the direction of the associations. Our results will aid in defining the key characteristics of CIMP tumors and ultimately provide the clinical community with necessary information to identify patients with CIMP tumors. Improving understanding of these associations can identify potential pathways that characterize CIMP and help researchers develop pathway-specific cancer prevention and treatment strategies.

Methods

This systematic review follows the publishing guidelines as set forth by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [12]. It has been registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42016034181). Eligibility criteria were determined a priori and required that studies examined the association of CIMP with clinical, pathologic, and molecular characteristics among patients with sporadic CRC. We excluded all studies that focused on hereditary CRC syndrome (familial adenomatous polyposis or lynch syndrome), studies focusing on other cancers or premalignant CRC lesions such as adenomas or polyps, and articles that did not have a clear description of the measurement or quantification of CIMP. Only original research articles published in English-language were included; comments, editorials, dissertations, conference proceedings, reviews, etc., were excluded. The three main concepts that made up our search were CIMP, sporadic CRC, and clinical/pathologic and molecular characteristics.

Search Strategy

We searched Medline (Ovid), PubMed (NLM), Embase (Ovid), and PsycINFO (Ovid) with the help of a health sciences librarian (H.V.) with systematic review experience who developed all searches. The initial searches were completed in April 2016; an updated PubMed search was completed April 5, 2018. A combination of MeSH terms and title, abstract, and keywords was used to develop the initial Medline search. The search was then adapted to search other databases. Supplemental Material (Appendix 1) provides the search strategies used for each database. RefWorks (ProQuest) was used to store all citations found in the search and to check for duplicates. Search strategies and results were tracked using one of a series of Microsoft Excel workbooks designed specifically for systematic reviews by the health sciences librarian (H.V.) [13].

An online random-number generator (https://www.random.org/integers/) was used to create a random sample of 146 numbers that were then input into an Excel workbook designed specifically for the interrater reliability test [13]. These numbers corresponded to line numbers within the Excel workbook which resulted in a random sample of titles and abstracts; authors and journal titles were not included in the sample. Two authors (S.A., P.A.) independently screened the sample and reached moderate agreement (Cohen's κ = 0.77) [14]. Screening discrepancies of the sample dataset were resolved at which time they then independently screened all titles and abstracts, still blinded to authors and journal titles, using an Excel workbook designed specifically for this step of the systematic review process. Data were compiled into a single Excel workbook, and consensus was reached on items in which there was disagreement. Articles considered for inclusion were independently reviewed by the two authors (S.A., P.A.), and consensus was reached by discussion on any disagreements for inclusion.

Data Abstraction

The primary author (S.A.) extracted the following data for each study: basic study characteristics, including study design, primary author of the study, cohort description, and country of study; panel markers and/or methodology used to measure CIMP, cutoff for classifying various CIMP groups, and prevalence of each CIMP subgroup; patient demographics including age and gender; clinical, pathologic, and molecular characteristics; and the prevalence of each characteristic across CIMP subgroups. Most common classification included classifying CIMP into two groups: CIMP-H and CIMP-0. However certain studies classified CIMP as CIMP-H, CIMP-L, and CIMP-0. Few studies also classified CIMP as CIMP-Positive (CIMP+) and CIMP-Negative (CIMP−). For consistency, we have labeled CIMP-H and CIMP-positive as CIMP-H, and CIMP-L, CIMP-0, and CIMP-negative as CIMP-0.

Meta-Analysis

Pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the association of CIMP with the various characteristics. Additionally, for continuous variables (age), a standardized mean difference was measured for CIMP groups. A random-effects model was utilized to measure these associations. A P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. A measure of heterogeneity (I2) was also calculated. In addition, the Egger test was used to measure bias due to small size effects. Funnel plots were generated to study the distribution of effect sizes. In addition, the pooled prevalence of each characteristic was measured in the CIMP-H and CIMP-0 subgroups wherever possible.

Quality Assessment

We performed quality assessment on included studies. For cohort and case control studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was utilized [15]. The scale assesses quality of included studies on three groups: Selection; Comparability, and Assessment. For cohort studies, these include selection of cohort, comparability of exposed and nonexposed cohort, and assessment of outcome and follow-up data. For case control, these include selection of cases and controls, comparability of cases and controls, and ascertainment of exposure, including ascertainment of cases and controls and response rates. Reviewers rate studies on scale of 0-4 for selection, scale of 0-2 for comparability, and scale of 0-3 for ascertainment respectively.

Results

Our search identified 4377 abstracts for initial screening. After removal of duplicates, a total of 2313 abstracts were screened by two authors (S.A., P.A.). The Cohen κ statistic was 0.77, indicating good agreement between the two authors. We identified 749 abstracts in this process eligible for full-text review. After full-text review of 749 studies, 337 publications were selected for final data abstraction process. The main reasons for exclusion included conference abstracts or studies focused on other cancers or other CRC lesions such as premalignancies. Figure 1 outlines the entire screening process and reasons for exclusion. Of the 337 publications; we included 122 for final meta-analysis in this project.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart outlining the literature search process. CRC, colorectal cancer; CIMP, CpG island methylator phenotype.

Study Characteristics

We identified 122 publications; 113 publications utilized data from cohort studies, 8 utilized case control studies, and 1 utilized data from a randomized clinical trial. Most studies were from the United States, Japan, and Australia. For each characteristic, the data distribution across CIMP groups was assessed from the cohort with largest sample size identified in the literature to minimize bias due to repetitive data abstraction from the same patient population.

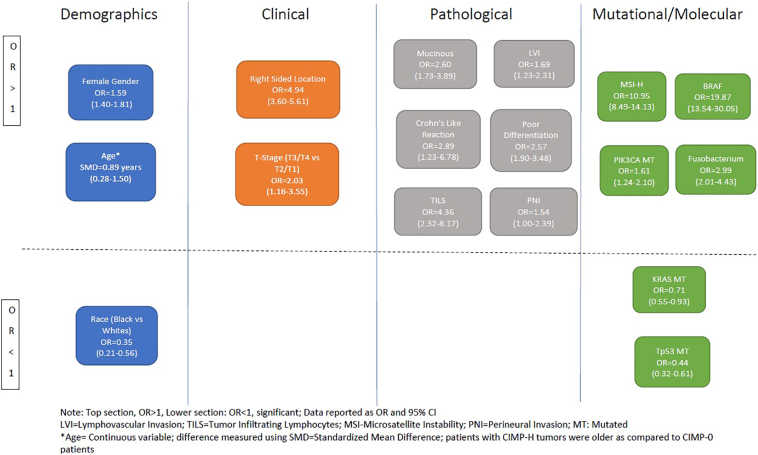

We obtained data for multiple characteristics with its association across CIMP groups. However, to make meaningful conclusions, we performed meta-analysis on 27 characteristics described below. Of 337 articles, 215 had insufficient data for inclusion into meta-analysis for factors assessed in this project, leaving 122 included publications for inclusion in final analysis. Below is a summary of the demographic, clinical, pathologic, mutational, and molecular characteristics that were reviewed and studied for their association with CIMP in the literature. Table 1 provides a summary of our meta-analysis including pooled OR and summary pooled estimates (prevalence) of various characteristics across CIMP-H group. Figure 2 provides a summary of significant associations identified in our analysis. Appendix 2 provides forest plots for each of the characteristics and funnel plots for assessment of bias.

Table 1.

Summary Estimates for Association of CIMP Status with Clinical, Pathological, Molecular, and Mutational Characteristics Using Meta-Analysis Approach

| Characteristic | No. of Studies | No. of CRC cases | Pooled OR/SMD | 95% CI | I2, % | Egger P | Prevalence, % of CIMP-H | 95% CI for prevalence, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||||||||

| Age at diagnosis | 16 | 3948 | 0.89 years | 0.28-1.50 | 97.9 | .35 | NA | NA |

| Gender | 56 | 22,950 | ||||||

| Male | Ref | 18 | 15-20 | |||||

| Female | 1.59 | 1.40-1.81 | 58.1 | .36 | 26 | 22-29 | ||

| Race | ||||||||

| NHW | 4 | 7948 | Ref | 93 | 92-95 | |||

| NHB | 0.35 | 0.21-0.56 | 0 | .7 | 2 | 0-5 | ||

| Hispanics | 1.04 | 0.70-1.55 | 0 | .7 | 3 | 1-5 | ||

| Family history of CRC | 4 | 4291 | ||||||

| No | Ref | 46 | 33-58 | |||||

| Yes | 0.93 | 0.72-1.20 | 29.6 | .23 | 13 | 10-16 | ||

| Clinical | ||||||||

| T staging | ||||||||

| T1/2 | 11 | 3255 | Ref | 8 | 4-11 | |||

| T3/4 | 2.03 | 1.16-3.55 | 60.8 | .48 | 18 | 13-23 | ||

| N staging | ||||||||

| N0 | 17 | 3502 | Ref | 16 | 12-20 | |||

| N1/2 | 1.14 | 0.87-1.49 | 38.9 | .05 | 17 | 13-21 | ||

| M staging | ||||||||

| M0 | 6 | 1343 | Ref | 23 | 12-34 | |||

| M1 | 0.92 | 0.65-1.57 | 38.5 | .10 | 18 | 10-26 | ||

| Overall stage | ||||||||

| I-II | 35 | 12,668 | Ref | Stage I=13 | 11-16 | |||

| III-IV | 1.01 | 0.87-1.17 | 48.1 | .83 | Stage II=19 | 16-22 | ||

| Stage III=18 | 16-21 | |||||||

| Stage IV=16 | 12-19 | |||||||

| Localization | ||||||||

| Left | 56 | 20,782 | Ref | 11 | 10-13 | |||

| Right | 4.94 | 3.60-5.61 | 80.0 | .06 | 36 | 32-41 | ||

| Synchronous CRC | ||||||||

| No | 3 | 1243 | Ref | 16 | 13-19 | |||

| Yes | 1.66 | 0.66-4.08 | 45.5 | .5 | 22 | 8-37 | ||

| Liver mets | ||||||||

| No | 3 | 395 | Ref | 29 | 17-40 | |||

| Yes | 0.91 | 0.52-1.60 | 23.8 | .02 | 26 | 11-41 | ||

| Pathological Characteristics | ||||||||

| LVI | ||||||||

| No | 9 | 1572 | Ref | 23 | 15-31 | |||

| Yes | 1.69 | 1.23-2.31 | 18.1 | .75 | 32 | 22-43 | ||

| TILS | ||||||||

| No | 5 | 2053 | Ref | 14 | 8-19 | |||

| Yes | 4.36 | 2.32-8.17 | 79.9 | .39 | 42 | 21-63 | ||

| PLS | ||||||||

| No | 5 | 2270 | Ref | 12 | 9-16 | |||

| Yes | 1.74 | 0.92-3.30 | 75.8 | .32 | 22 | 12-32 | ||

| Vascular invasion | ||||||||

| No | 9 | 2067 | Ref | 15 | 9-21 | |||

| Yes | 1.20 | 0.77-1.88 | 35.7 | .47 | 11 | 8-15 | ||

| PNI | ||||||||

| No | 4 | 890 | Ref | 35 | 18-52 | |||

| Yes | 1.54 | 1.00-2.39 | 0 | .20 | 39 | 28-51 | ||

| Crohn-like infiltrate | ||||||||

| No | 4 | 2398 | Ref | 11 | 7-15 | |||

| Yes | 2.89 | 1.23-6.78 | 88.4 | .68 | 28 | 9-48 | ||

| Signet ring cell histology | ||||||||

| No | 4 | 1673 | Ref | 14 | 6-22 | |||

| Yes | 3.10 | 0.98-9.86 | 46.5 | .44 | 44 | 36-53 | ||

| Mucinous histology | ||||||||

| No | 21 | 6297 | Ref | 15 | 12-19 | |||

| Yes | 2.60 | 1.73-3.89 | 80.9 | .86 | 30 | 24-37 | ||

| Differentiation | ||||||||

| Well/moderate | Ref | 20 | 16-24 | |||||

| Poor | 26 | 7095 | 2.57 | 1.90-3.48 | 70.4 | .59 | 37 | 30-45 |

| Mutational and Molecular Characteristics | ||||||||

| Tp53 mutation | ||||||||

| WT | Ref | 30 | 23-38 | |||||

| MT | 19 | 7021 | 0.44 | 0.32-0.61 | 78.7 | .04 | 14 | 11-17 |

| PIK3CA mutation | ||||||||

| WT | 6 | 3285 | Ref | 16 | 13-19 | |||

| MT | 1.61 | 1.24-2.10 | 12.5 | .49 | 22 | 18-26 | ||

| APC mutation | ||||||||

| WT | 5 | 1641 | Ref | 38 | 18-58 | |||

| MT | 0.56 | 0.16-1.84 | 93.3 | .81 | 26 | 9-42 | ||

| MSI | ||||||||

| MSS | 54 | 21,994 | Ref | 15 | 13-16 | |||

| MSI-H | 10.95 | 8.49-14.13 | 83 | .21 | 61 | 55-66 | ||

| BRAF mutation | ||||||||

| WT | 44 | 20,615 | Ref | 12 | 10-13 | |||

| MT | 20.17 | 13.54-30.05 | 88.4 | .03 | 68 | 57-79 | ||

| KRAS mutation | ||||||||

| WT | 41 | 16,784 | Ref | 22 | 19-25 | |||

| MT | 0.71 | 0.55-0.93 | 81.3 | .48 | 17 | 14-20 | ||

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | ||||||||

| Negative | 4 | 1392 | Ref | 17 | 10-24 | |||

| Positive | 2.99 | 2.01-4.43 | 0 | .65 | 38 | 17-59 | ||

NHW, non-Hispanic whites; NHB, non-Hispanic blacks; WT, wild type; MT, mutated; MSS, microsatellite stable; MSI, microsatellite-instable high; CRC, colorectal cancer.

Figure 2.

Significant associations of CIMP with demographic, clinical, genetic and molecular, or pathologic characteristics as identified in the meta-analysis. OR, odds ratio; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Demographic Characteristics

We explored the association of CIMP with demographic characteristics including age at diagnosis, race/ethnicity, gender, and family history of CRC. The association of CIMP with age at diagnosis (continuous variable) was explored in 16 studies representing a total of 3948 cases [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]. While CIMP-H patients were older at diagnosis compare to CIMP-0 patients (P < .001), the magnitude of this difference was modest (standardized mean difference = 0.89 years, 95% CI = 0.28-1.50 years), confirming previous association of CIMP-H with older age. We also studied the association of CIMP with race/ethnicity across four studies [32], [33], [34], [35]. Using non-Hispanic whites as a reference group, we identified that patients of black race had substantially lower likelihood of having a CIMP-H tumor (pooled OR = 0.35, 95% CI = 0.21-0.56). In contrast, the likelihood of CIMP in Hispanic patients was indistinguishable from non-Hispanic white patients (OR = 1.04, 95% CI = 0.70-1.55). The association of CIMP-H with gender was studied across 56 studies, representing a total of 22,950 CRC patients [9], [16], [17], [19], [20], [21], [22], [24], [25], [27], [28], [30], [31], [33], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77]. The pooled prevalence of CIMP-H in males and females was 18% (95% CI = 15%-20%) and 26% (95% CI = 22%-29%), respectively, indicating a predisposition for CIMP-H tumors towards female gender (pooled OR = 1.59, 95% CI = 1.40-1.81). Finally, we did not observe any association of CIMP with family history of cancer across four studies [35], [47], [78], [79]. The pooled OR for family history of CRC in the CIMP-H subgroup compared with the CIMP-0 subgroup was 0.93 (95% CI = 0.72-1.20, I2 = 29.6%). Hence, our analysis identified a strong inverse association between CIMP-H and black race and confirmed previously reported associations of CIMP with older age and female sex. See Appendix 2, Figures 1-10, for forest and funnel plots for association of CIMP with demographic characteristics.

Clinical Characteristics

We studied the association of CIMP with tumor location, T staging, N staging, M staging, overall stage, well as synchronous CRC and presence of liver metastases. The association of CIMP with tumor location (right colon vs left colon + rectum) was investigated in 56 studies, representing a total of 20,782 CRC patients [16], [17], [19], [23], [24], [25], [28], [29], [30], [31], [33], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [47], [48], [50], [51], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [72], [73], [74], [76], [77], [78], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88]. The pooled OR for right-sided location (as opposed to left-sided or rectal location) in the CIMP-H subgroup compared with the CIMP-0 subgroup was 4.84 (95% CI = 3.60-5.61, I2 = 80%). The association of CIMP with T staging was investigated across 11 studies, representing 3255 cases [20], [21], [36], [50], [51], [62], [65], [69], [71], [77], [89]. The pooled OR for T-stage (T3/T4) (as compared to T1/T2) in the CIMP-H subgroup compared with CIMP-0 subgroup was 2.03 (95% CI = 1.16-3.55, I2 = 61%). The association of CIMP with overall stage was investigated across 35 studies, representing a total of 12,668 CRC patients [16], [17], [20], [22], [24], [28], [33], [37], [38], [40], [41], [44], [45], [47], [48], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [63], [65], [66], [68], [72], [73], [74], [78], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93]. The pooled OR for stage III/IV disease (compared to I/II disease) in the CIMP-H subgroup compared with the CIMP-0 subgroup was 1.01 (95% CI = 0.87-1.17, I2 = 48.1%). In pooled analysis, no association was observed for CIMP with N staging [OR for N1/2 vs N0 = 1.14 (95% CI = 0.87-1.49, I2 = 38.9%)] [16], [20], [21], [25], [36], [39], [50], [51], [61], [65], [69], [71], [72], [75], [77], [83], [94] and M staging [OR for M1/M2 vs M0 = 0.92 (95% CI = 0.56-1.57, I2 = 38.5%)] [20], [39], [45], [53], [65], [95]. Similarly, no association of CIMP was observed with synchronous CRC [58], [96], [97] or presence of liver metastases [61], [98], [99].

Our results confirm the previously reported association of CIMP with right-sided tumor location. Additionally, we identified CIMP-H tumors to be associated with advanced T-stage (T3/T4). In summary, our results identified no association between CIMP and overall stage, as well as N or M staging, synchronous CRC, or the presence of liver metastases. See Appendix 2, Figures 11-24, for funnel plots and forest plots for association of clinical factors with CIMP.

Pathologic Characteristics

We studied the association of CIMP with key pathological characteristics in CRC tumors including lymphovascular invasion (LVI), tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILS), peritumoral lymphocytes (PLS), vascular invasion, perineural invasion (PNI), presence of Crohn-like infiltrates, mucinous histology, and signet ring cell histologic characteristics. We investigated the association of CIMP with LVI in nine studies, representing 1572 CRC cases, and identified CIMP-H tumors to be associated with LVI as compared to CIMP-0 tumors (OR = 1.69, 95% CI = 1.23-2.31, I2 = 18.1%) [30], [38], [43], [45], [50], [59], [62], [65], [72]. The association of CIMP with TILS was investigated in five studies, representing 2015 CRC cases [19], [38], [69], [100], [101]. The pooled OR for presence of TILS in the CIMP-H subgroup compared with the CIMP-0 subgroup was 4.36 (95% CI = 2.32-8.17, I2 = 79.9%). A borderline association was identified for CIMP-H tumors with PLS [OR = 1.74 (95% CI = 0.92-3.30, I2 = 75.8%)] in pooled analysis of five studies [44], [69], [77], [100], [101] and with signet ring histology [OR = 3.10 (95% CI = 0.98-9.86, I2 = 46.5%)] across four studies [52], [58], [102], [103]. We found borderline association of CIMP with PNI across four studies [30], [38], [50], [62]. The pooled OR for PNI across CIMP-H groups was 1.54 (95% CI = 1.00-2.39, I2 = 0%). CIMP-H tumors were also found to be associated with presence of Crohn-like infiltrate [OR = 2.89 (95% CI = 1.23-6.78, I2 = 88.4%] in pooled analysis of four studies [44], [69], [100], [101]. No associations were observed for CIMP status with vascular invasion [OR = 1.20 (95% CI = 0.77-1.88, I2 = 35.7%)] across nine studies [45], [52], [65], [69], [71], [72], [77], [83], [104]. Finally, we also confirmed association of CIMP-H tumors with mucinous histology [OR = 2.60 (95% CI = 1.73-3.89, I2 = 80.90%)] in pooled analysis of 21 studies [19], [25], [30], [36], [39], [41], [43], [44], [54], [56], [58], [65], [66], [72], [76], [77], [81], [83], [84], [103], [105] and with poor differentiation [OR = 2.57 (95% CI = 1.90-3.84, I2 = 70.4%)] in pooled analysis of 26 studies [17], [25], [30], [33], [36], [37], [39], [41], [43], [44], [45], [50], [52], [53], [54], [58], [67], [69], [72], [74], [75], [76], [81], [84], [92], [105]. In summary, our results indicated that CIMP was associated with TILS, Crohn-like infiltrates, and LVI. CIMP-H was common in patients with signet ring cell histologic characteristics, but the association was not significant. See Figures 25-42 for funnel plots and forest plots for association of pathological factors with CIMP in Appendix 2.

Mutational and Molecular Characteristics

We studied the association of CIMP with key mutations in CRC pathogenesis including mutations in KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, TP53, and APC as well as microsatellite instability (MSI) and presence of Fusobacterium nucleatum. We calculated both pooled prevalence and ORs for each of these associations as shown in Table 1. Using meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of CIMP-H in BRAF MT, BRAF WT, KRAS MT, KRAS WT, PIK3CA MT, PIK3CA WT, TP53 MT, TP53 WT, APC MT, and APC WT groups was 68%, 12%, 17%, 22%, 22%, 16%, 14%, 30%, 26%, and 38%, respectively. Similarly, the pooled prevalence of CIMP-H in MSI-H and MSS groups was 61% and 15%, respectively. The prevalence of high levels of Fusobacterium nucleatum in CIMP-H tumors was 38%, and the prevalence of low levels of FB in CIMP-H tumors was 15%.

CIMP-H was found to be associated with BRAF Mutation [OR = 20.17 (95% CI = 13.54-30.05, I2 = 83%)] [16], [17], [19], [22], [24], [25], [26], [28], [33], [37], [39], [40], [41], [42], [47], [48], [49], [52], [58], [59], [60], [62], [64], [66], [68], [69], [70], [72], [77], [78], [82], [83], [84], [93], [95], [106], [107], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [113], [114] and PIK3CA mutation [OR = 1.61 (95% CI = 1.24-2.10, I2 = 12.5%)] [55], [76], [115], [116], [117], [118]. An inverse association of CIMP-H tumors was observed with TP53 mutation [OR = 0.44 (95% CI = 0.32-0.61, I2 = 78.7%)] [24], [41], [44], [53], [55], [62], [64], [69], [74], [78], [83], [100], [105], [113], [119], [120], [121], [122], [123] and KRAS mutation [OR = 0.71 (95% CI = 0.55-0.93, I2 = 81%)] [16], [19], [21], [23], [24], [25], [26], [31], [33], [37], [38], [39], [40], [43], [47], [48], [52], [53], [55], [59], [60], [62], [67], [69], [70], [71], [72], [74], [76], [77], [78], [83], [84], [105], [107], [110], [111], [113], [121], [124], [125]. No associations were observed with APC mutation [OR = 0.56 (95% CI = 0.16-1.84, I2 = 93.3%)] [32], [55], [78], [113], [126]. We also confirmed previously reported association of CIMP-H with microsatellite instability (MSI-H) status [OR = 10.95 (95% CI = 8.49-14.13, I2 = 83%)] among CRC patients [16], [17], [19], [20], [23], [25], [28], [33], [34], [36], [38], [39], [40], [41], [43], [44], [47], [48], [50], [55], [58], [59], [60], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [70], [72], [74], [77], [80], [81], [82], [84], [95], [107], [109], [110], [111], [112], [127], [128], [129], [130], [131], [132], [133], [134], [135], [136], [137], [138]. Finally, we also observed a positive association of CIMP-H tumors with presence of high levels of fusobacterium nucleatum [OR = 2.99 (95% CI = 2.01-4.43, I2 = 0%)] [3], [64], [139], [140].

In summary, our results showed that CIMP was associated with PIK3CA mutations and inversely associated with TP53 mutations. CIMP was also associated with Fusobacterium nucleatum. In addition, we validated the previously reported association of CIMP with BRAF mutations, MSI, and KRAS mutations. No association was observed between CIMP and APC mutations. See Figures 43-56 for funnel plots and forest plots for association of mutational/molecular factors with CIMP in Appendix 2.

Quality Assessment

A visual assessment of funnel plots identified possible evidence of publication bias in association of CIMP with BRAF mutation, Tp53 mutation, gender, differentiation, and location. Egger's regression test was utilized to study whether studies with small sample size introduced possible publication bias in our analysis. We found evidence of possible publication bias due to low sample size in the association of CIMP with N staging (P = .05), liver metastases (P = .02), BRAF mutation (P = .04), and TP53 mutation (P = .04). However, for other factors, possible different factors could play a role in introducing heterogeneity (I2 values of >50%) or publication bias, including selective reporting (of outcomes or exposures), differences in CIMP methodologies across studies, sampling variation, or by chance alone. To assess quality of studies included, refer to Appendix 3 (Cohort Studies) and Appendix 4 (Case Control Study) for quality assessment of included studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale.

Discussion

Our systematic review confirmed the previously reported association of CIMP with high MSI, BRAF mutations, lack of KRAS mutations, poor differentiation, mucinous histologic characteristics, right-sided tumor location, female sex, and older age, In addition to this, to the best of our knowledge, we are the first to confirm association of CIMP with T staging (T3/T4), TILS, Crohn-like infiltrates, LVI, wild-type TP53, PIK3CA mutations, and high levels of Fusobacterium nucleatum, and an inverse association with black race using meta-analysis. In addition, CIMP was common among patients with signet ring cell histologic characteristics and those with PNI. CIMP in CRC provides a unique opportunity to study molecular mechanisms that lead to epigenetic changes in cancer and the contributions of these changes to the development of the disease [141].

Consistent with previous reports, we found that CIMP was associated with high MSI and BRAF mutations. These are thought to arise as events in the serrated adenoma pathway. BRAF mutations are thought to be early events in CIMP cancers, inhibiting normal apoptosis of colonic epithelial cells [11]. CIMP also seems to be more likely to develop when a BRAF mutation is present and the polyp is in the proximal colonic environment [142]. Other studies have hypothesized that the pathways of development differ between high-MSI cancers with BRAF mutations and microsatellite-stable cancers with BRAF mutations [143]. High-MSI CRCs may develop from a subset of hyperplastic polyps (which often have BRAF mutations and CIMP-H), and microsatellite-stable cancers with BRAF mutations may develop from adenomas with BRAF mutations. Alternatively, both types may share a similar initial pathway but diverge with respect to clinical aggressiveness; methylation of hMLH1 may occur in a subset of tumors that then develop high MSI [143]. In experimental models, CIMP-dependent DNA hypermethylation and transcriptional inactivation of IGFBP7 were shown to mediate BRAF V600E-induced cellular senescence and apoptosis [141]. Future prospective studies should explore this relationship in patients undergoing screening colonoscopy to determine the sequence of events.

We found that CIMP was associated with PIK3CA mutations. PIK3CA mutations occur in 10%-30% of CRC patients [144]. A mutation in PIK3CA stimulates the AKT (protein kinase B) pathway and promotes cell growth in various cancers, possibly through increased expression of fatty acid synthetase (FASN) [145]. FASN is an important regulator of energy balance and has been shown to be associated with cancer development [146]. A previous study by Nosho et al. identified higher levels of FASN expression in CIMP-H versus non-CIMP tumors; however, this should be further explored as a possible mechanism underlying the association of CIMP with PIK3CA [146].

Immunotherapy, as a tool for cancer management, has gained significant importance. Additionally, activation of immune system and subsequent immune reaction play an important role in tumor microenvironment in suppressing tumor development and progression [147]. The presence of TILS provides evidence that the host's immune system is attempting to eliminate the tumor, and this is an important favorable prognostic factor in CRC [148], [149]. Specific subsets of TILS (CD57+, CD8+, CD45RO+, or FOXP3+ cells) have been associated with improved clinical outcome in CRC [150]. TILS can trigger preferential lysis of cancer cells by recognizing enhanced expression of abnormally expressed antigens presented in the context of HLA molecules [151]. Recent molecular classification by TCGA identifies CIMP− tumors to be associated with CMS 1 phenotype which involves CRC tumors with strong immunogenic response to tumors and favorable survival [97]. In recent years, immunotherapy as a tool to stimulate immune system to target cancer and work to change tumor microenvironment has rapidly gained significant importance, and MSI-H cancers are favorable targets for immunotherapy-related clinical trials including pembrolizumab [152], [153]. Previous studies have also reported MSI cancers to be associated with expression of programmed cell death (PD1) intraepithelial lymphocytes and have shown favorable response on anti-PD1 therapy [154], [155]. The presence of TILS is considered a hallmark of MSI-high cancers, possibly due to truncated peptides produced by frameshift mutations in MSI-high cancers that have been shown to be immunogenic and to contribute to the host immune response and improved survival [156]. Although no association has been identified between CIMP and specific levels of TILS like FOXP3 levels or CD8 levels, this association of CIMP with TILS highlights possible role of the immune system in CIMP CRC and should be further explored by MSI status [156]. This also makes CIMP+ tumors potential targets for immunotherapy trials including anti-PD1 therapy as CIMP-H has been shown to be associated with PD-1–positive T cells in subset of MSI-H cancers [157]. Recently, the TIME (Tumor Immunity in the MicroEnvironment) classification system was developed based on high/low levels of tumor CD274 (PD-L1) expression and presence/absence of TILS to classify cancer subtypes [158], [159]. Hanada et al. identified CIMP-H tumors to be associated with TIME-2 and 3 subtypes characterized by presence of TILS [147]. Similarly, presence of Crohn-like infiltrate indicates association of CIMP with peritumoral lymphoid aggregates and role of immune system in MSI and CIMP cancers [160]. Crohn-like infiltrates confer favorable prognosis in CRC, indicating that the host immune response plays a role in preventing cancer progression and a possible mechanism affecting prognosis in CIMP tumors.

Microbiome has shown to play a distinct role in cancer development and progression, including response to chemotherapeutic agents [161], [162]. Our analysis identified that CIMP was associated with high levels of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Fusobacterium species are highly heterogeneous and opportunistic pathogens and have been linked to periodontitis, appendicitis, and inflammatory bowel diseases [64]. Clostridium Fusobacterium nucleatum is an anaerobic commensal, thought to provide a microenvironment for survival of CRC cells in the gut, especially in CIMP-H CRC [64], [163]. Preliminary studies have also identified Fusobacterium nucleatum to be involved in development of CRC through the serrated adenoma pathway [164]. In pilot studies, evidence suggest that fusobacterium may play a key role in CRC development and modulate response to chemotherapy among CRC patients; however, these results have limited generalizability due to their small sample size and need further validation in future prospective studies [165], [166], [167]. Fusobacterium species have been shown to have particular characteristics, including invasiveness and an adherent and proinflammatory nature, sharing common features and pathways with inflammation in CIMP-H CRC [64], [163]. Additionally, Fusobacterium might induce release of reactive oxygen species leading to chronic inflammation, possibly leading to high levels of aberrant base 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-guanine (8-oxoG), most commonly modified by reactive oxygen species [164]. FN may also lead to development of CIMP-H CRC through possible activation of NF-κB, a transcription factor that is a key regulator of gene expression associated with tumor growth and an important link between inflammation and cancer [168]. Future studies should correlate diet history with levels of Fusobacterium in CIMP-H patients to explore the possible influence of diet on metabolites and microenvironment that influence development of CIMP tumors [169]. Additionally, utilizing evidence from metagenomic studies, utilizing gene markers of FN, namely, butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase, may prove a vital biomarker in predicting development of CIMP-H CRCs [170].

We also found CIMP-H tumors to be associated with advanced T-stage (T3/T4) among CRC patients. T staging is an important predictor of cancer outcomes, with advanced T staging indicating greater invasion of the tumor through colorectum and with higher T-stage indicating invasion through muscularis propria into pericolorectal tissues or visceral peritoneum. Though no clear evidence/basis exists underlying this mechanism, limited studies have identified CIMP-H tumors to have greater diameter/size as compared to CIMP-0 tumors [52], [54]. Finally, we found that CIMP-H was inversely associated with black race (compared with white). Blacks face a disproportionately higher burden of CRC as compared to other racial/ethnic groups in the United States [171]. Possible factors underlying these differences include genetic factors, lifestyle factors, cancer screening behaviors, and geographical variations as well as differences in gene expression underlying inflammatory pathways [171], [172]. Previous studies have shown differences in the incidence of CIMP-H between people of Anglo-Celtic origin and those of southern European origin [131]. Hence, further studies are needed to identify genetic basis for differences in prevalence of CIMP-H phenotype across racial groups. However, these analyses were based on data from three studies and hence need further validation.

Different molecular subtypes of CRC may have different environmental, genetic, and lifestyle risk factors, and investigation of possible risk factors for each molecular subtype may lead to a better understanding of how to prevent the disease [131]. Our findings that CIMP-H is associated with TILS, LVI, Crohn-like infiltrates, and Fusobacterium nucleatum highlight the role of the immune system mechanisms on development of CIMP-H. Many of these characteristics might be attributed to MSI-high status which is characterized by a strong immune response and possibly good prognosis in patients with high-MSI cancers. However, the association of CIMP status with clinical outcomes (overall survival) shows a trend towards poor survival, although it remains inconsistent owing to differences in methodologies, patient characteristics, and variables utilized in multivariable analysis [173]. Hence, the association of CIMP with these characteristics, including clinical outcomes, should be measured after stratifying by MSI status to understand the true effect of CIMP in CRC population [174].

Our study has several strengths and limitations. Our search strategy was broad and was not restricted to any specific methodology for measuring CIMP. The search was conducted using systematic Excel workbooks especially developed for systematic reviews. Training and discussions ensured that we incorporated and identified relevant articles. Finally, we excluded all articles on precancerous lesions. A major limitation in CIMP research is the lack of a standard definition for measuring and quantifying CIMP in CRC patients [8]. We did a comprehensive abstraction of data to allow for maximum understanding of CIMP in CRC. We found considerable heterogeneity in our measured associations, which can be attributed to differences in patient selection, racial or ethnic differences in CRC, tools or methods used for measuring CIMP, confounding by other factors such as lifestyle or family history, and differences in tissue preservation techniques [8]. In addition, CRC incidence varies across racial and ethnic groups and global regions, and we did not restrict our search to any region or country. For meta-analysis with less than 10 studies, results should be interpreted more cautiously as Egger test has low power to perform accurate bias assessments with <10 studies. Finally, no gold standard exists for assessing quality of nonobservational studies.

In summary, our systematic review provides a comprehensive assessment of CIMP in CRC and highlights distinct characteristics that define CIMP. While limited or small-scale studies had previously investigated these associations individually across individual studies, using the meta-analysis methods, we observed potential associations that warrant further exploration and validation in larger studies. Additionally, many of these characteristics are shared among high-MSI cancers, and future studies should assess these associations stratified by MSI status to study the molecular pathways impacting CIMP tumors independent of MSI status.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Search Strategies CRC-CIMP

Forest Plots and Funnel Plots

Cohort Studies Assessment

Case Control Studies Assessment

Additional Information

All manuscripts must contain an Additional Information section and should include the appropriate headings from the list below:

-

•

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The study was approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center Institutional Review Board.

-

•

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

-

•

Availability of data and material: All necessary publications have been cited in this manuscript.

-

•

Conflict of interest: No conflicts of interest to disclose.

-

•

Funding: We would like to acknowledge following grant: NIH P30-CA016672 for supporting this project.

-

•

Authors' contributions

-

1.

Shailesh Advani: conceptualization, screening of articles, writing, data analysis

-

2.

Pragati Advani: conceptualization, screening of articles, writing, data analysis

-

3.

Stacia DeSantis: writing, data analysis

-

4.

Derek Brown: writing, data analysis

-

5.

Helena VonVille: conceptualization, writing, data analysis

-

6.

Michael Lam: conceptualization, writing

-

7.

Jonathan Loree: conceptualization, writing

-

8.

Amir Mehrvarz Sarshekeh: conceptualization, writing

-

9.

Jan Bressler: conceptualization, writing

-

10.

David S. Lopez: conceptualization, writing

-

11.

Carrie-Daniel MacDougall: conceptualization, writing

-

12.

Michael D. Swartz: conceptualization, writing

-

13.

Scott Kopetz: conceptualization, writing, data analysis

Acknowledgments

Department of Scientific Publications, MD Anderson Cancer Center. We would also like to acknowledge our funding source: NIH P30-CA016672 for supporting this project.

References

- 1.Renaud F, Vincent A, Mariette C, Crépin M, Stechly L, Truant S, Copin MC, Porchet N, Leteurtre E, Van Seuningen I. MUC5 AC hypomethylation is a predictor of microsatellite instability independently of clinical factors associated with colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(12):2811–2821. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li T, Liao X, Lochhead P, Morikawa T, Yamauchi M, Nishihara R, Inamura K, Kim SA, Mima K, Sukawa Y. SMO expression in colorectal cancer: associations with clinical, pathological, and molecular features. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(13):4164–4173. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3888-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ito M, Kanno S, Nosho K, Sukawa Y, Mitsuhashi K, Kurihara H, Igarashi H, Takahashi T, Tachibana M, Takahashi H. Association of Fusobacterium nucleatum with clinical and molecular features in colorectal serrated pathway. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(6):1258–1268. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali RH, Marafie MJ, Bitar MS, Al-Dousari F, Ismael S, Haider HB, Al-Ali W, Jacob SP, Al-Mulla F. Gender-associated genomic differences in colorectal cancer: clinical insight from feminization of male cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(10):17344–17365. doi: 10.3390/ijms151017344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baylin SB, Jones PA. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome — biological and translational implications. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:726–734. doi: 10.1038/nrc3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang M, Ou J, Hutchinson L, Green MR. The BRAF oncoprotein functions through the transcriptional repressor MAFG to mediate the CpG island methylator phenotype. Mol Cell. 2014;55:904–915. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toyota Minoru, Ahuja Nita, Ohe-Toyota Mutsumi, Herman James G, Baylin Stephen B, Issa Jean-Pierre J. CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96(15):8681–8686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zong Liang, Abe Masanobu, Ji Jiafu, Zhu Wei-Guo, Duonan Yu. Tracking the correlation between CpG island methylator phenotype and other molecular features and clinicopathological features in human colorectal cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016;7(3) doi: 10.1038/ctg.2016.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Kirkner GJ, Kraft P, Loda M, Fuchs CS. Evaluation of markers for CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) in colorectal cancer by a large population-based sample. J Mol Diagn. 2007;9(3):305–314. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.060170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes LA, Khalid-de Bakker CA, Smits KM, van den Brandt PA, Jonkers D, Ahuja N, Herman JG, Weijenberg MP, van Engeland M. The CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer: progress and problems. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2012;1825(1):77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes LA, Khalid-de Bakker CA, Smits KM, van den Brandt PA, Jonkers D, Ahuja N, Herman JG, Weijenberg MP, van Engeland M. The CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer: progress and problems. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2012;1825(1):77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.VonVille H. 2015. Excel Workbooks for Systematic Reviews. [In] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med. 2012;22:276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wells G. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analysis. 2004. http://www,ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology.oxford.htm

- 16.Alvi MA, Loughrey MB, Dunne P, McQuaid S, Turkington R, Fuchs MA, McGready C, Bingham V, Pang B, Moore W. Molecular profiling of signet ring cell colorectal cancer provides a strong rationale for genomic targeted and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies. Br J Cancer. 2017;117(2):203. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cleven AH, Derks S, Draht MX, Smits KM, Melotte V, Van Neste L, Tournier B, Jooste V, Chapusot C, Weijenberg MP. CHFR promoter methylation indicates poor prognosis in stage II microsatellite stable colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(12):3261–3271. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curtin K, Slattery ML, Ulrich CM, Bigler J, Levin TR, Wolff RK, Albertsen H, Potter JD, Samowitz WS. Genetic polymorphisms in one-carbon metabolism: associations with CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) in colon cancer and the modifying effects of diet. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28(8):1672–1679. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iacopetta B, Grieu F, Phillips M, Ruszkiewicz A, Moore J, Minamoto T, Kawakami K. Methylation levels of LINE-1 repeats and CpG island loci are inversely related in normal colonic mucosa. Cancer Sci. 2007;98(9):1454–1460. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibrahim AE, Arends MJ, Silva AL, Wyllie AH, Greger L, Ito Y, Vowler SL, Huang TH, Tavaré S, Murrell A. Sequential DNA methylation changes are associated with DNMT3B overexpression in colorectal neoplastic progression. Gut. 2011;60(4):499–508. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.223602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jo P, Jung K, Grade M, Conradi LC, Wolff HA, Kitz J, Becker H, Rüschoff J, Hartmann A, Beissbarth T. CpG island methylator phenotype infers a poor disease-free survival in locally advanced rectal cancer. Surgery. 2012;151(4):564–570. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jover R, Nguyen TP, Pérez–Carbonell L, Zapater P, Payá A, Alenda C, Rojas E, Cubiella J, Balaguer F, Morillas JD. 5-Fluorouracil adjuvant chemotherapy does not increase survival in patients with CpG island methylator phenotype colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(4):1174–1181. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karpinski P, Walter M, Szmida E, Ramsey D, Misiak B, Kozlowska J, Bebenek M, Grzebieniak Z, Blin N, Laczmanski L. Intermediate-and low-methylation epigenotypes do not correspond to CpG island methylator phenotype (low and-zero) in colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(2):201–208. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0157. [Epub 2012 Nov 21] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marisa L, de Reyniès A, Duval A, Selves J, Gaub MP, Vescovo L, Etienne-Grimaldi MC, Schiappa R, Guenot D, Ayadi M. Gene expression classification of colon cancer into molecular subtypes: characterization, validation, and prognostic value. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Min BH, Bae JM, Lee EJ, Yu HS, Kim YH, Chang DK, Kim HC, Park CK, Lee SH, Kim KM. The CpG island methylator phenotype may confer a survival benefit in patients with stage II or III colorectal carcinomas receiving fluoropyrimidine-based adjuvant chemotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2011;11(1):344–353. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nosho K, Yamamoto H, Takahashi T, Mikami M, Hizaki K, Maehata T, Taniguchi H, Yamaoka S, Adachi Y, Itoh F. Correlation of laterally spreading type and JC virus with methylator phenotype status in colorectal adenoma. Hum Pathol. 2008;39(5):767–775. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambuudash O, Kim HS, Cho MY. Lack of aberrant methylation in an adjacent area of left-sided colorectal cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2017;58:749–755. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2017.58.4.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka H, Deng G, Matsuzaki K, Kakar S, Kim GE, Miura S, Sleisenger MH, Kim YS. BRAF mutation, CpG island methylator phenotype and microsatellite instability occur more frequently and concordantly in mucinous than non-mucinous colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(11):2765–2771. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Roon EH, van Puijenbroek M, Middeldorp A, van Eijk R, de Meijer EJ, Erasmus D, Wouters KA, van Engeland M, Oosting J, Hes FJ. Early onset MSI-H colon cancer with MLH1 promoter methylation, is there a genetic predisposition? BMC Cancer. 2010;10(1):180–189. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Long Y, Xu Y, Guan Z, Lian P, Peng J, Cai S, Cai G. Prognostic and predictive value of CpG island methylator phenotype in patients with locally advanced nonmetastatic sporadic colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/436985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weisenberger DJ, Siegmund KD, Campan M, Young J, Long TI, Faasse MA, Kang GH, Widschwendter M, Weener D, Buchanan D. CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2006;38(7):787. doi: 10.1038/ng1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samowitz WS, Slattery ML, Sweeney C, Herrick J, Wolff RK, Albertsen H. APC mutations and other genetic and epigenetic changes in colon cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5(2):165–170. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanchez JA, Krumroy L, Plummer S, Aung P, Merkulova A, Skacel M, DeJulius KL, Manilich E, Church JM, Casey G. Genetic and epigenetic classifications define clinical phenotypes and determine patient outcomes in colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96(10):1196–1204. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen L, Kondo Y, Hamilton SR, Rashid A, Issa JPJ. P14 methylation in human colon cancer is associated with microsatellite instability and wild-type p53. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(3):626–633. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weisenberger DJ, Levine AJ, Long TI, Buchanan DD, Walters R, Clendenning M, Rosty C, Joshi AD, Stern MC, Le Marchand L. Association of the colorectal CpG island methylator phenotype with molecular features, risk factors, and family history. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015 doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahn JB, Chung WB, Maeda O, Shin SJ, Kim HS, Chung HC, Kim NK, Issa JPJ. DNA methylation predicts recurrence from resected stage III proximal colon cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(9):1847–1854. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.An B, Kondo Y, Okamoto Y, Shinjo K, Kanemitsu Y, Komori K, Hirai T, Sawaki A, Tajika M, Nakamura T. Characteristic methylation profile in CpG island methylator phenotype-negative distal colorectal cancers. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(9):2095–2105. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ang PW, Loh M, Liem N, Lim PL, Grieu F, Vaithilingam A, Platell C, Yong WP, Iacopetta B, Soong R. Comprehensive profiling of DNA methylation in colorectal cancer reveals subgroups with distinct clinicopathological and molecular features. BMC Cancer. 2010;10(1):227–235. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bae JM, Kim JH, Kang GH. Molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer and their clinicopathologic features, with an emphasis on the serrated neoplasia pathway. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:406–412. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2015-0310-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barault L, Charon-Barra C, Jooste V, de la Vega MF, Martin L, Roignot P, Rat P, Bouvier AM, Laurent-Puig P, Faivre J. Hypermethylator phenotype in sporadic colon cancer: study on a population-based series of 582 cases. Cancer Res. 2008;68(20):8541–8546. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dahlin AM, Palmqvist R, Henriksson ML, Jacobsson M, Eklöf V, Rutegård J, Öberg Å, Van Guelpen BR. The role of the CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer prognosis depends on microsatellite instability screening status. Clin Cancer Res. 2010 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2594. [pp.1078-0432] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donada M, Bonin S, Barbazza R, Pettirosso D, Stanta G. Management of stage II colon cancer-the use of molecular biomarkers for adjuvant therapy decision. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13(1):36–49. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fu T, Liu Y, Li K, Wan W, Pappou EP, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Kerner Z, Baylin SB, Wolfgang CL, Ahuja N. Tumors with unmethylated MLH1 and the CpG island methylator phenotype are associated with a poor prognosis in stage II colorectal cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7(52):86480. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hawkins N, Norrie M, Cheong K, Mokany E, Ku SL, Meagher A, O'connor T, Ward R. CpG island methylation in sporadic colorectal cancers and its relationship to microsatellite instability. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(5):1376–1387. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hokazono K, Ueki T, Nagayoshi K, Nishioka Y, Hatae T, Koga Y, Hirahashi M, Oda Y, Tanaka M. A CpG island methylator phenotype of colorectal cancer that is contiguous with conventional adenomas, but not serrated polyps. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(5):1937–1944. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hughes LA, Simons CC, van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA, de Goeij AF, de Bruïne AP, van Engeland M, Weijenberg MP. Body size, physical activity and risk of colorectal cancer with or without the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jia M, Jansen L, Walter V, Tagscherer K, Roth W, Herpel E, Kloor M, Bläker H, Chang-Claude J, Brenner H. No association of CpG island methylator phenotype and colorectal cancer survival: population-based study. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(11):1359. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kakar S, Deng G, Sahai V, Matsuzaki K, Tanaka H, Miura S, Kim YS. Clinicopathologic characteristics, CpG island methylator phenotype, and BRAF mutations in microsatellite-stable colorectal cancers without chromosomal instability. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132(6):958–964. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-958-CCCIMP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karpinski P, Myszka A, Ramsey D, Kielan W, Sasiadek MM. Detection of viral DNA sequences in sporadic colorectal cancers in relation to CpG island methylation and methylator phenotype. Tumor Biol. 2011;32(4):653–659. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0165-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim CH, Huh JW, Kim HR, Kim YJ. CpG island methylator phenotype is an independent predictor of survival after curative resection for colorectal cancer: a prospective cohort study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:1469–1474. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim HC, Roh SA, KIM JS, YU CS, Kim JC. CpG island methylation as an early event during adenoma progression in carcinogenesis of sporadic colorectal cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20(12):1920–1926. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kohonen-Corish MR, Tseung J, Chan C, Currey N, Dent OF, Clarke S, Bokey L, Chapuis PH. KRAS mutations and CDKN2A promoter methylation show an interactive adverse effect on survival and predict recurrence of rectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;134(12):2820–2828. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laskar RS, Ghosh SK, Talukdar FR. Rectal cancer profiling identifies distinct subtypes in India based on age at onset, genetic, epigenetic and clinicopathological characteristics. Mol Carcinog. 2015;54:1786–1795. doi: 10.1002/mc.22250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li X, Hu F, Wang Y, Yao X, Zhang Z, Wang F, Sun G, Cui BB, Dong X, Zhao Y. CpG island methylator phenotype and prognosis of colorectal cancer in Northeast China. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/236361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luo Y, Wong CJ, Kaz AM, Dzieciatkowski S, Carter KT, Morris SM, Wang J, Willis JE, Makar KW, Ulrich CM. Differences in DNA methylation signatures reveal multiple pathways of progression from adenoma to colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(2):418–429. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ostwald C, Linnebacher M, Weirich V, Prall F. Chromosomally and microsatellite stable colorectal carcinomas without the CpG island methylator phenotype in a molecular classification. Int J Oncol. 2009;35:321–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oyama K, Kawakami K, Maeda K, Ishiguro K, Watanabe G. The association between methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism and promoter methylation in proximal colon cancer. Anticancer Res. 2004;24(2B):649–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perea J, Rueda D, Canal A, Rodríguez Y, Álvaro E, Osorio I, Alegre C, Rivera B, Martínez J, Benítez J. Age at onset should be a major criterion for subclassification of colorectal cancer. J Mol Diagn. 2014;16(1):116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saadallah-Kallel A, Abdelmaksoud-Dammak R, Triki M, Charfi S, Khabir A, Sallemi-Boudawara T, Mokdad-Gargouri R. Clinical and prognosis value of the CIMP status combined with MLH1 or p16INK4a methylation in colorectal cancer. Med Oncol. 2017;34(8):147–156. doi: 10.1007/s12032-017-1007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seth R, Crook S, Ibrahem S, Fadhil W, Jackson D, Ilyas M. Concomitant mutations and splice variants in KRAS and BRAF demonstrate complex perturbation of the Ras/Rafsignalling pathway in advanced colorectal cancer. Gut. 2009;58(9):1234–1241. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.159137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shen L, Catalano PJ, Benson AB, O'Dwyer P, Hamilton SR, Issa JPJ. Association between DNA Methylation and Shortened Survival in Patients with Advanced Colorectal Cancer Treated with 5-Fluorouracil–Based Chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(20):6093–6098. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shiovitz S, Bertagnolli MM, Renfro LA, Nam E, Foster NR, Dzieciatkowski S, Luo Y, Lao VV, Monnat RJ, Jr., Emond MJ. CpG island methylator phenotype is associated with response to adjuvant irinotecan-based therapy for stage III colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(3):637–645. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Slattery ML, Herrick JS, Mullany LE, Wolff E, Hoffman MD, Pellatt DF, Stevens JR, Wolff RK. Colorectal tumor molecular phenotype and miRNA: expression profiles and prognosis. Mod Pathol. 2016;29(8):915. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tahara T, Yamamoto E, Suzuki H, Maruyama R, Chung W, Garriga J, Jelinek J, Yamano HO, Sugai T, An B. Fusobacterium in colonic flora and molecular features of colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2014 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cancer Genome Atlas N Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Van Guelpen B, Dahlin AM, Hultdin J, Eklöf V, Johansson I, Henriksson ML, Cullman I, Hallmans G, Palmqvist R. One-carbon metabolism and CpG island methylator phenotype status in incident colorectal cancer: a nested case–referent study. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(4):557–566. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9484-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Van Rijnsoever M, Grieu F, Elsaleh H, Joseph D, Iacopetta B. Characterisation of colorectal cancers showing hypermethylation at multiple CpG islands. Gut. 2002;51(6):797–802. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.6.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vedeld HM, Merok M, Jeanmougin M, Danielsen SA, Honne H, Presthus GK, Svindland A, Sjo OH, Hektoen M, Eknæs M. CpG island methylator phenotype identifies high risk patients among microsatellite stable BRAF mutated colorectal cancers. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(5):967–976. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Walsh MD, Clendenning M, Williamson E, Pearson SA, Walters RJ, Nagler B, Packenas D, Win AK, Hopper JL, Jenkins MA. Expression of MUC2, MUC5AC, MUC5B, and MUC6 mucins in colorectal cancers and their association with the CpG island methylator phenotype. Mod Pathol. 2013;26(12):1642. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weisenberger DJ, Levine AJ, Long TI, Buchanan DD, Walters R, Clendenning M, Rosty C, Joshi AD, Stern MC, Le Marchand L. Association of the colorectal CpG island methylator phenotype with molecular features, risk factors, and family history. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(3):512–519. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1161. [Epub 2015 Jan 13] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Williamson JS, Jones HG, Williams N, Griffiths AP, Jenkins G, Beynon J, Harris DA. Extramural vascular invasion and response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer: influence of the CpG island methylator phenotype. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;9(5):209. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v9.i5.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yagi K, Akagi K, Hayashi H, Nagae G, Tsuji S, Isagawa T, Midorikawa Y, Nishimura Y, Sakamoto H, Seto Y. Three DNA methylation epigenotypes in human colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2006. [pp.1078-0432] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yamamoto E, Suzuki H, Yamano HO, Maruyama R, Nojima M, Kamimae S, Sawada T, Ashida M, Yoshikawa K, Kimura T. Molecular dissection of premalignant colorectal lesions reveals early onset of the CpG island methylator phenotype. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(5):1847–1861. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yamashita K, Dai T, Dai Y, Yamamoto F, Perucho M. Genetics supersedes epigenetics in colon cancer phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2003;4(2):121–131. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang Q, Dong Y, Wu W, Zhu C, Chong H, Lu J, Yu D, Liu L, Lv F, Wang S. Detection and differential diagnosis of colon cancer by a cumulative analysis of promoter methylation. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1206–1214. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang X, Shimodaira H, Soeda H, Komine K, Takahashi H, Ouchi K, Inoue M, Takahashi M, Takahashi S, Ishioka C. CpG island methylator phenotype is associated with the efficacy of sequential oxaliplatin-and irinotecan-based chemotherapy and EGFR-related gene mutation in Japanese patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2016;21(6):1091–1101. doi: 10.1007/s10147-016-1017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zlobec I, Bihl M, Foerster A, Rufle A, Lugli A. Comprehensive analysis of CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP)-high,-low, and-negative colorectal cancers based on protein marker expression and molecular features. J Pathol. 2011;225(3):336–343. doi: 10.1002/path.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Simons CCJM, Hughes LAE, Smits KM, Khalid-de Bakker CA, De Bruïne AP, Carvalho B, Meijer GA, Schouten LV, van den Brandt PA, Weijenberg MV. A novel classification of colorectal tumors based on microsatellite instability, the CpG island methylator phenotype and chromosomal instability: implications for prognosis. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(8):2048–2056. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ward RL, Williams R, Law M, Hawkins NJ. The CpG island methylator phenotype is not associated with a personal or family history of cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7618–7621. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Anacleto C, Leopoldino AM, Rossi B, Soares FA, Lopes A, Rocha JCC, Caballero O, Camargo AA, Simpson AJ, Pena SD. Colorectal cancer "methylator phenotype": fact or artifact? Neoplasia. 2005;7(4):331–335. doi: 10.1593/neo.04502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Arain MA, Sawhney M, Sheikh S, Anway R, Thyagarajan B, Bond JH, Shaukat A. CIMP status of interval colon cancers: another piece to the puzzle. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(5):1189. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Deng G, Kakar S, Tanaka H, Matsuzaki K, Miura S, Sleisenger MH, Kim YS. Proximal and distal colorectal cancers show distinct gene-specific methylation profiles and clinical and molecular characteristics. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(9):1290–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ferracin M, Gafa R, Miotto E, Veronese A, Pultrone C, Sabbioni S, Lanza G, Negrini M. The methylator phenotype in microsatellite stable colorectal cancers is characterized by a distinct gene expression profile. J Pathol. 2008;214(5):594–602. doi: 10.1002/path.2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McInnes T, Zou D, Rao DS, Munro FM, Phillips VL, McCall JL, Black MA, Reeve AE, Guilford PJ. Genome-wide methylation analysis identifies a core set of hypermethylated genes in CIMP-H colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):228–239. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3226-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Perea J, Cano JM, Rueda D, García JL, Inglada L, Osorio I, Arriba M, Pérez J, Gaspar M, Fernández-Miguel T. Classifying early-onset colorectal cancer according to tumor location: new potential subcategories to explore. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5(7):2308. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sawada T, Yamamoto E, Yamano HO, Nojima M, Harada T, Maruyama R, Ashida M, Aoki H, Matsushita HO, Yoshikawa K. Assessment of epigenetic alterations in early colorectal lesions containing BRAF mutations. Oncotarget. 2016;7(23):35106. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sugai T, Habano W, Jiao YF, Tsukahara M, Takeda Y, Otsuka K, Nakamura SI. Analysis of molecular alterations in left-and right-sided colorectal carcinomas reveals distinct pathways of carcinogenesis: proposal for new molecular profile of colorectal carcinomas. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8(2):193–201. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.050052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yamauchi M, Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Imamura Y, Qian ZR, Nishihara R, Liao X, Waldron L, Hoshida Y, Huttenhower C. Assessment of colorectal cancer molecular features along bowel subsites challenges the conception of distinct dichotomy of proximal versus distal colorectum. Gut. 2012 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300865. [pp.gutjnl-2011] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bae JM, Kim JH, Cho NY, Kim TY, Kang GH. Prognostic implication of the CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancers depends on tumour location. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(4):1004–1012. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kang KJ, Min BH, Ryu KJ, Kim KM, Chang DK, Kim JJ, Rhee JC, Kim YH. The role of the CpG island methylator phenotype on survival outcome in colon cancer. Gut Liver. 2015;9(2):202–208. doi: 10.5009/gnl13352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bond CE, Umapathy A, Buttenshaw RL, Wockner L, Leggett BA, Whitehall VL. Chromosomal instability in BRAF mutant, microsatellite stable colorectal cancers. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nosho K, Irahara N, Shima K, Kure S, Kirkner GJ, Schernhammer ES, Hazra A, Hunter DJ, Quackenbush J, Spiegelman D. Comprehensive biostatistical analysis of CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer using a large population-based sample. PLoS One. 2008;3(11):e3698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen KH, Lin YL, Liau JY, Tsai JH, Tseng LH, Lin LI, Liang JT, Lin BR, Hung JS, Chang YL. BRAF mutation may have different prognostic implications in early-and late-stage colorectal cancer. Med Oncol. 2016;33(5):39–47. doi: 10.1007/s12032-016-0756-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Messick CA, Church JM, Liu X, Ting AH, Kalady MF. Stage III colorectal cancer: molecular disparity between primary cancers and lymph node metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(2):425–431. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0783-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bruin SC, He Y, Mikolajewska-Hanclich I, Liefers GJ, Klijn C, Vincent A, Verwaal VJ, De Groot KA, Morreau H, Van Velthuysen MF. Molecular alterations associated with liver metastases development in colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(2):281. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nosho K, Kure S, Irahara N, Shima K, Baba Y, Spiegelman D, Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS, Ogino S. A prospective cohort study shows unique epigenetic, genetic, and prognostic features of synchronous colorectal cancers. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(5):1609–1620. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cancer Genome Atlas Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487(7407):330. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Konishi K, Watanabe Y, Shen L, Guo Y, Castoro RJ, Kondo K, Chung W, Ahmed S, Jelinek J, Boumber YA. DNA methylation profiles of primary colorectal carcinoma and matched liver metastasis. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lee S, Cho NY, Choi M, Yoo EJ, Kim JH, Kang GH. Clinicopathological features of CpG island methylator phenotype-positive colorectal cancer and its adverse prognosis in relation to KRAS/BRAF mutation. Pathol Int. 2008;58(2):104–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2007.02197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bae JM, Rhee YY, Kim KJ, Wen X, Song YS, Cho NY, Kim JH, Kang GH. Are clinicopathological features of colorectal cancers with methylation in half of CpG island methylator phenotype panel markers different from those of CpG island methylator phenotype–high colorectal cancers? Hum Pathol. 2016;47(1):85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kawasaki T, Ohnishi M, Suemoto Y, Kirkner GJ, Liu Z, Yamamoto H, Loda M, Fuchs CS, Ogino S. WRN promoter methylation possibly connects mucinous differentiation, microsatellite instability and CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(2):150. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bae JM, Kim MJ, Kim JH, Koh JM, Cho NY, Kim TY, Kang GH. Differential clinicopathological features in microsatellite instability-positive colorectal cancers depending on CIMP status. Virchows Arch. 2011;459(1):55–63. doi: 10.1007/s00428-011-1080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Inamura K, Yamauchi M, Nishihara R, Kim SA, Mima K, Sukawa Y, Li T, Yasunari M, Zhang X, Wu K. Prognostic significance and molecular features of signet-ring cell and mucinous components in colorectal carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(4):1226–1235. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4159-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kokelaar RF, Jones HG, Williamson J, Williams N, Griffiths AP, Beynon J, Jenkins GJ, Harris DA. DNA hypermethylation as a predictor of extramural vascular invasion (EMVI) in rectal cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2018;19(3):214–221. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2017.1416933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Samowitz WS, Albertsen H, Herrick J, Levin TR, Sweeney C, Murtaugh MA, Wolff RK, Slattery ML. Evaluation of a large, population-based sample supports a CpG island methylator phenotype in colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(3):837–845. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ang PW, Li WQ, Soong R, Iacopetta B. BRAF mutation is associated with the CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer from young patients. Cancer Lett. 2009;273:221–224. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Beg S, Siraj AK, Prabhakaran S, Bu R, Al-Rasheed M, Sultana M, Qadri Z, Al-Assiri M, Sairafi R, Al-Dayel F. Molecular markers and pathway analysis of colorectal carcinoma in the Middle East. Cancer. 2015;121(21):3799–3808. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bond CE, Bettington ML, Pearson SA, McKeone DM, Leggett BA, Whitehall VL. Methylation and expression of the tumour suppressor, PRDM5, in colorectal cancer and polyp subgroups. BMC Cancer. 2015;15(1):20–29. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1011-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Maeda T, Suzuki K, Togashi K, Nokubi M, Saito M, Tsujinaka S, Kamiyama H, Konishi F. Sessile serrated adenoma shares similar genetic and epigenetic features with microsatellite unstable colon cancer in a location-dependent manner. Exp Ther Med. 2011;2(4):695–700. doi: 10.3892/etm.2011.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Minarikova P, Benesova L, Halkova T, Belsanova B, Suchanek S, Cyrany J, Tuckova I, Bures J, Zavoral M, Minarik M. Longitudinal molecular characterization of endoscopic specimens from colorectal lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(20):4936. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i20.4936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]