Abstract

Objective: To assess and refine competencies for the clinical research data management profession.

Materials and Methods: Based on prior work developing and maintaining a practice standard and professional certification exam, a survey was administered to a captive group of clinical research data managers to assess professional competencies, types of data managed, types of studies supported, and necessary foundational knowledge.

Results: Respondents confirmed a set of 91 professional competencies. As expected, differences were seen in job tasks between early- to mid-career and mid- to late-career practitioners. Respondents indicated growing variability in types of studies for which they managed data and types of data managed.

Discussion: Respondents adapted favorably to the separate articulation of professional competencies vs foundational knowledge. The increases in the types of data managed and variety of research settings in which data are managed indicate a need for formal education in principles and methods that can be applied to different research contexts (ie, formal degree programs supporting the profession), and stronger links with the informatics scientific discipline, clinical research informatics in particular.

Conclusion: The results document the scope of the profession and will serve as a foundation for the next revision of the Certified Clinical Data ManagerTM exam. A clear articulation of professional competencies and necessary foundational knowledge could inform the content of graduate degree programs or tracks in areas such as clinical research informatics that will develop the current and future clinical research data management workforce.

Keywords: clinical research informatics, professional competencies, clinical data management

INTRODUCTION

The Society for Clinical Data Management (SCDM) published the first version of the Good Clinical Data Management Practices (GCDMP) in 2000 and initiated professional certification for those who manage data for clinical trials in 2004. The Certified Clinical Data Manager (CCDMTM) exam was revised in 2008. Today, there are 592 CCDMs, and the GCDMP, which serves as the practice standard for the management of data for prospective clinical studies, has been translated into multiple languages, referenced by regulatory authorities, and downloaded over 100 000 times. The increases over the last decade in (1) the types of data managed in any “single” study; (2) the technologies introduced into data collection, processing, and reporting for clinical studies; and (3) the breadth of study designs together signify a drift in professional responsibilities and a need to update both the GCDMP and the certification exam. In late 2015, the SCDM Board of Trustees initiated a joint revision of the GCDMP and the CCDMTM exam. The revision process began with a survey of the job tasks of professional clinical data managers to understand changes in the responsibilities of those who manage data for clinical studies since the 2008 exam revision. Here, we report the results of that survey.

BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE

Competencies, foundational knowledge, and application areas

Management of clinical research data is largely performed with ad hoc and consensus methods informed by federal regulations and guidance.1 Within these general parameters, organizations develop their own operating procedures. While currently under revision, the Good Clinical Data Management Practices (GCDMP) document2 was previously based almost solely on consensus best practice since its first version was published in 2000.2

Study data managers in clinical and translational research in industry and academia are generally trained on the job through institutionally developed training, apprenticeship, or self-learning. In this model, each institution, and in academia sometimes each investigator, must train his or her own data management staff. Such training is often highly focused on past practices and organizational procedures rather than on underlying theories, principles, and methods based in evidence. Training that lacks such grounding in underlying science leaves trainees without knowledge that can be applied to different types of data, therapeutic areas, and research scenarios. In the absence of this grounding and with very few formal academic programs supporting the profession, clinical data managers lack the credibility conferred by evidence-based practices that members of clinical study teams from professions with such foundations enjoy.

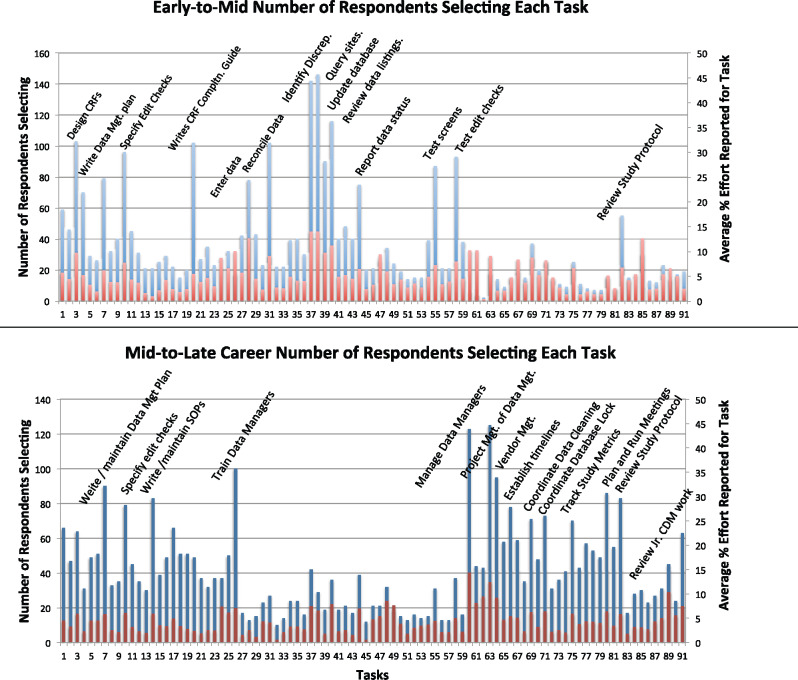

Formalizing the relationship of a profession with the underlying science starts with clear articulation of professional competencies and the foundational knowledge that supports them. Furthermore, cornerstones of educational theory and general medical education3–5 emphasize the importance of applying foundational knowledge in competencies requiring the use of higher-order cognitive abilities such as evaluation, synthesis, and creation. Thus, in support of preparing for the upcoming revision of the competencies for the clinical research data management profession, the SCDM made a deliberate and separate articulation of (1) foundational knowledge, (2) practice standards, and (3) professional competencies. The relationship between these and items on the certification exam that assess them is depicted in Figure 1. Briefly, a competency domain for SCDM (there are 8 of them in total) is associated with 1 or more competency. For each competency, there are 1 or more items on the professional certification exam. A competency is also associated with 1 or more application contexts. For clinical research data management, we defined 3 important application contexts: the type of study for which the data will be managed, the research setting in which the data will be managed, and the type (most often types) of data to be managed. A competency is also associated with 1 or more practice standards and 1 or more foundational knowledge topics. The links from competency to practice standard and foundational knowledge are instantiated by (1) citing supporting evidence for practice standards and (2) associating references to foundational knowledge sources with exam items. The scope of clinical research data management is narrower than the field of clinical research informatics (CRI), a sub-area of biomedical informatics. However, the growing CRI literature provides evidence on which to base practice. Additionally, established theories, principles, and methods from other disciplines such as cognitive engineering, operations engineering, statistics, and information science are directly applicable to the practice of clinical research data management and directly inform practice. These links are being strengthened in the current revision of the GCDMP.

Figure 1.

Relationships between competencies, foundational knowledge, practice standards, and application context.

History of clinical data management practice standards

The first synthesis of evidence relevant to clinical research data management, the Greenberg Report, was published in 1967 and concentrated on organization, review, and administration of cooperative studies. By design, the report contained little detail on clinical research data management methods.6 In 1990, Dr Morris Collen,7 in his paper “Clinical Research Databases: A Historical Review,” presented a review of data collection and processing methods for existing clinical research databases. This paper was followed in 1995 by a special issue of Controlled Clinical Trials (now Clinical Trials) that contained a collection of 5 review papers documenting current practice.8–12 However, the more than 40 contributors to the issue were largely from academic-based clinical trials.13,14 Further, the recommendations were largely consensus-based, and many of the methods differed from those used in clinical studies intended for marketing authorization and falling under the regulatory authority of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). To provide a basis for practice for these FDA-regulated clinical studies, in 1998 SCDM convened the Good Clinical Data Management Practices committee, which published the first version of the GCDMP in 2000.2 The initial version of the GCDMP suffered from the same lack of supporting evidence that prompted the Clinical Trials 1995 special issue, and historically the GCDMP has been a consensus-based document.

The extent of evidence applicable to practice is currently being assessed. Today, there is a growing body of work identifying, translating from other areas, or testing and articulating foundational knowledge applicable to the collection and management of data for clinical studies. With this growing body of work in CRI, we begin the journey of realizing the vision of Dr Collen7 and other early thought leaders and firmly anchoring the practice of clinical data management in science, and at the same time raising the bar for evidence-based practice in clinical research data management.

Clinical research data management as a growing profession

There are thousands of clinical and translational research team members collecting and processing research data in the United States alone. In addition to the 2000 or so largely industry-based members of SCDM, a recent survey conducted at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center identified 555 individuals in jobs likely to involve data collection, processing, or management, with 230 of them confirming data management job responsibilities and opting in to notifications for continuing education.15 Extrapolating from this estimate across the National Institutes of Health funded Clinical and Translational Science Award institutions, there are likely over 14 000 individuals collecting, processing, or otherwise managing data for clinical studies in academia alone. Recognition of the growing workforce prompted previous acknowledgment of clinical data management as a Department of Labor job category in the US (ONET job code 15‐2041.02). While the job code was initiated by the clinical research data management community, today it is also used more broadly than research, including for professionals handling data in health care settings.

The Clinical Research Data Management competencies were first probed in 1998 by SCDM with the initial CDM Task List,16 then again in 2003 to support development of the initial 2004 version of the CCDM certification exam, and in 2008 for the most recent exam revision. In 1998, the society identified professional responsibilities through consensus, and in later years more objectively through surveys of the membership. Starting with the 2004 certification exam, competencies have been defined and maintained at a granular task level, eg, “utilizes metafiles or control files, vendor data files and loading software to load electronic data.”

The 91 job tasks used for the survey reported here (Table 1) were compiled from 2 sources: (1) the competencies from the 2008 CCDMTM exam, containing 112 subcompetencies organized under 26 core competencies,17 and (2) the clinical research data management work domain ontology.18,19 Briefly, the work domain ontology was developed by applying semantic methods to the 2008 competencies to expand the set in order to exhaustively cover the domain but at a higher level of abstraction. The work domain ontology was vetted in focus groups at an SCDM meeting. The higher level of abstraction of the latter was adopted for this work, and the 2 sources were again compared by the study team as a quality check, resulting in 91 mutually exclusive competency statements falling into 8 categories: design, training, data processing, programming, testing, personnel management, coordination and project management, and review (Table 1). In keeping with Bunge-Wand-Weber representational theory for goodness of representation,20 each competency category was reviewed for completeness, mutual exclusivity, and consistency of the level of detail. While exhaustiveness is the intent of professional competencies, it cannot be claimed in the context of a growing profession; exhaustiveness (or, for that matter, adequacy) of a competency set can only be assessed at points in time.

Table 1.

Clinical Research Data Management Tasks

| Design Tasks | Data Processing Tasks | Personnel Management Tasks |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Identify data to be collected | 27. Collect study data | 60. Manage CDMs |

| 2. Define study data elements | 28. Enter data | 61. Manage data processing staff |

| 3. Design data collection forms | 29. Load data | 62. Manage computer programmers |

| 4. Annotate forms | 30. Integrate or link data | |

| 5. Design workflows and data flows | 31. Reconcile data, eg, lab, safety | |

| 6. Write and maintain study-specific data management procedures | 32. Data imputation | Coordination and Management Tasks |

| 33. Transform data | 63. Manage DM projects | |

| 7. Write and maintain data management plan | 34. Code medications | 64. Manage vendors |

| 35. Code adverse events | 65. Manage project workload | |

| 8. Specify database tables | 36. Code other data | 66. Establish timelines |

| 9. Specify data entry screens | 37. Identify data discrepancies | 67. Coordinate system/DM start-up |

| 10. Specify edit checks | 38. Query sites re discrepancies | 68. Coordinate data collection/entry |

| 11. Specify reports | 39. Update database from queries | 69. Coordinate data cleaning |

| 12. Write data transfer specification | 70. Coordinate data transfers | |

| 40. Manual data listing review | 71. Coordinate database lock | |

| 13. Specify other programming | 41. Export data | 72. Coordinate site close-out |

| 14. Write or maintain organizational standard operating procedures | 42. Manage data system accounts | 73. Coordinate data archive |

| 15. Select data standards | 43. Archive study data | 74. Implement new data system |

| 16. Implement data standards | 44. Track and report data status | 75. Track and study data metrics |

| 17. Develop data standards | 45. Apply randomization codes | 76. Understand scope of work |

| 18. Manage organizational data standards | 77. Define scope of work | |

| 19. Respond to audit findings | Programming Tasks | 78. Identify and communicate risk |

| 20. Write case report form completion guide | 46. Program database tables | 79. Prepare for/host audits |

| 21. Define in-process data quality control | 47. Program data entry screens | 80. Plan and run meetings |

| 22. Write test plans | 48. Program edit checks | 81. Prepare and deliver presentation |

| 23. Provide content for project communications | 49. Program reports | |

| 50. Program ad hoc queries | Review Tasks | |

| 51. Program data imports | 82. Review study protocol | |

| Training Tasks | 52. Program data transformation | 83. Verify source documents |

| 24. Train data collectors | 53. Program data extracts | 84. Review tables |

| 25. Train data system users | 85. Review listings | |

| 26. Train data managers | Testing Tasks | 86. Review figures |

| 54. Test database tables | 87. Review clinical study report | |

| 55. Test data entry screens | 88. Audit database/data quality | |

| 56. Test load programming | 89. Review work of vendors | |

| 57. Test transform programming | 90. Review work of data processors | |

| 58. Test edit checks | ||

| 59. Test reports | 91. Review work of junior CDMs |

A competency is generally defined as some action that produces a result. Items such as “Understands what medication coding is and why it is important” represent foundational knowledge but are not associated with actions. These items were removed from the 2008 exam competency list and enumerated separately as foundational knowledge topics for the survey reported here.

METHODS

Objective

The objective of the study was to characterize the professional competencies of clinical research data managers, the types of studies to which the competencies are applied, the types of data managed, and the foundational knowledge needed.

Study design

The study was designed as a survey to be administered at the annual meeting of the Society for Clinical Data Management, September 20–23, 2015, in Washington, DC. Surveying conference attendees allowed for frequent face-to-face contact and opportunities for follow-up to assure a sufficient response rate. Prior to the conference, 500 attendees were anticipated and the target response rate was set at ≥70%. The survey was administered as an anonymous questionnaire (Supplementary Appendix S1). As such, the study was declared as “not involving human subjects” by the Duke University Institutional Review Board (protocol Pro00066249).

Survey design

The survey consisted of 10 questions organized into 4 parts (Supplementary Appendix 1). The 4 parts were: (1) demographics, (2) job tasks for early- to mid- and mid- to late-career data managers and the amount of effort spent on job tasks, (3) the context in which job tasks are performed, including types of studies for which data are managed and types of data managed, and (4) foundational knowledge required to perform clinical data management job tasks. The demographic questions were chosen for consistency with past information collected by SCDM from its membership to assess generalizability. For the purpose of the survey, a practicing clinical research data manager was defined as someone who at the time of the survey or within the last year managed data for clinical studies or had the responsibility of overseeing people who managed data for clinical studies. This question was added so that we could assess response rate and retain the ability to distinguish and include only responses from self-identified data managers in the analysis.

For the purpose of the survey, early- to mid-career data managers were defined as clinical research data managers with 0–3 years of experience in clinical research data management beyond college or time spent as a data entry operator or query processor. Mid- to late-career data managers were defined as having ≥5 years of experience in clinical research data management beyond college or time spent as a data entry operator or query processor. The gap was intentional to assure separation of the 2 categories, because individuals who progress from early to later career are in a state of learning new tasks and assuming responsibilities in a mentored fashion; on-the-job learning did not meet the intent of the question. Lastly, a question was added to solicit tasks that those who managed data for clinical studies would perform in the future. The hierarchical list of 91 clinical research data management job tasks was provided on the facing page. Respondents were instructed to enter the header to indicate all lower-level tasks within the category, to list individual tasks, or to write in tasks if a good match could not be identified from the list. The standardized task list was provided only to aid data collection and aggregation. Multiple form-completion options, from structured to completely open-ended, were provided so as to not impose a coding system on the responses. The responses were not constrained and respondents could enter anything they wished.

The third type of information solicited on the survey instrument characterized the context in which clinical data management competencies were applied. These included the types of studies for which data were managed, with response options including randomized controlled trials (RCTs), registries, correlative studies, comparative effectiveness research (CER), and “other,” with a place to describe types of studies not included in the response option list. The second context question asked respondents to indicate the types of data they managed at the time of the survey and the types of data they envisioned managing in the future. The response list was created from types of data included in the 2008 competencies, ie, lab data, case report form data, and safety data, and the experience of the study team. In keeping with the open philosophy of data collection, ie, not imposing a coding system on responses, respondents also had the option to choose listed items as well as to list other types of data not included in the list.

The fourth type of information asked on the survey regarded foundational knowledge topics (Table 2). This list was formed from a synthesis of the competencies and work domain ontology as described earlier and was expanded as the study team identified foundational knowledge not explicitly mentioned in prior competencies.

Table 2.

Foundational Knowledge Topics

| Therapeutic development fundamentals | Static and dynamic data principles |

|---|---|

| Clinical research fundamentals | Data lifecycle concepts |

| Scientific method | Data quality fundamentals |

| Introductory-level statistics | Relational database concepts |

| FDA regulation and guidance | Software development concepts |

| Health Insurance Portability and Accounting Act regulations | Relevant data element standards |

| Common rule | Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium submission data tabulation model and lab standards |

| Audit methodology fundamentals | Terminology standards: MedDRA, WHODRUG |

| FDA bioresearch monitoring procedures | Health-level 7 clinical research data standards |

| Quality system principles | Metadata definition and management |

| Process control fundamentals | Project management fundamentals |

| Medical terminology | Self-learning about data for new therapeutic areas |

Respondents were asked to mark any topics they felt were not necessary to professional competency in clinical data management and to add any they felt were missing.

Survey administration

The conference was conducted in 3 tracks and the survey was administered in all tracks throughout the 3-day conference. The demographic information appeared on the front cover so that respondents who answered no to question 4 (Are you a practicing clinical data manager?) could stop there and turn in their form. The survey was introduced at the plenary session. The purpose of the survey was explained and conference attendees were instructed on form completion. Surveys were placed at every seat for every session. Members of the study team and volunteers collected surveys at the meeting room doors and in the halls. Respondents could also turn in completed forms at the registration desk. Respondents were given stickers to place on their conference badges in exchange for completed surveys so that nonresponders could be spotted and prompted to participate. Response rates were periodically reported throughout the meeting to encourage participation.

Data were entered into Microsoft Excel and independently verified with the original form by a professional clinical research data manager. Corrections were made to a second copy of the data to assure traceability. The data were analyzed using SAS software.

RESULTS

Demographics

A total of 340 forms were received during the conference, yielding a 71% response rate. There were 479 regular registration conference attendees. Regular registrations did not include conference staff (5 people), delegates (6 people), exhibitors (180 people), and 1-day registrations (41 people). In all, 337 respondents indicated a sector in which they worked. Similar to membership in the SCDM in general, the majority of respondents (80%) worked in industry. Ten percent of the respondents indicated that they worked in academia and 4% indicated that they worked in state or federal government (both welcomed increasing trends); the remainder worked in sole proprietorships or indicated “other.”

Respondents indicated a variety of organization types, including academic research organizations; colleges or universities; contract research organizations; pharmaceutical, device, or biologic research and development companies; clinical investigational sites; health care facilities; and software providers. No respondents indicated that they worked for clinical labs, and 5.3% of respondents indicated that they worked in some other type of organization. The responses for organization type were also similar to the greater society membership, with the majority of respondents working for therapeutic research and development companies or contract research organizations.

A total of 238 respondents (70%) indicated that they were practicing clinical data managers. These respondents reported an average of 12 years working in clinical data management, and 70 of them (25%) reported being certified; 170 respondents reported that they were not certified data managers.

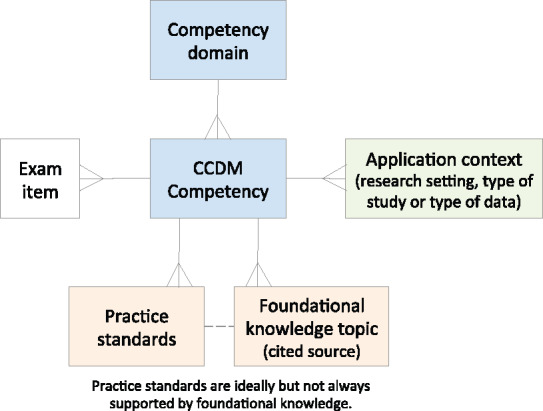

Types of studies managed

All 340 respondents completed the question about the types of studies for which they managed data. In the past, SCDM members primarily worked in phase I–IV studies, mostly in Randomized Clinical Trials (RCTs), with fewer members working in phase I studies or post-marketing or other registries. While most respondents (275, or 80%) still managed data for RCTs, respondents also managed data for other types of studies, including registries, correlative studies, Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER), and other study types (Figure 2). Of note, 108 (40%) of those who managed data for RCTs also managed data for registries, 42 (15%) who managed data for RCTs also managed data for correlative studies, 53 (19%) who managed data for RCTs also managed data for CER, and 41 (15%) who managed data for RCTs also managed data for other study types (Figure 2). All study types surveyed showed similar overlap (Figure 2), ie, clinical research data managers often manage data for more than 1 type of study.

Figure 2.

Types of studies for which respondents manage data.

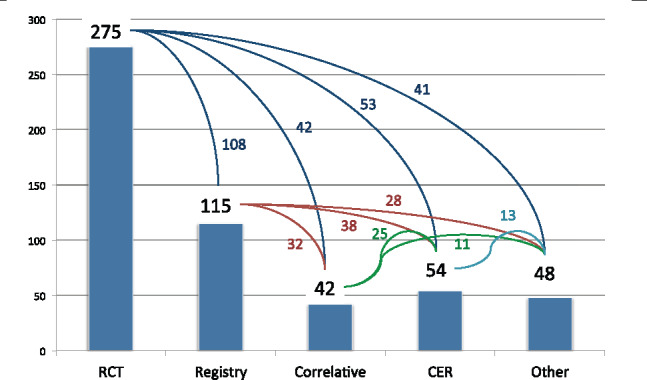

Types of data managed

The second context of application question probed the types of data managed by respondents. Of the respondents, 264 indicated 1 or more types of data that they manage today, with all 264 indicating more than 1 type of data managed and 213 (81%) indicating more than 5 types of data managed (Figure 3). The respondents projected that an even greater diversity of data will be managed in the future. Six additional types of data were identified from responses in the “other” field: electronic documents, social media data, biospecimen data, site performance data, enterprise project or program data, and metadata.

Figure 3.

Types of data managed by respondents.

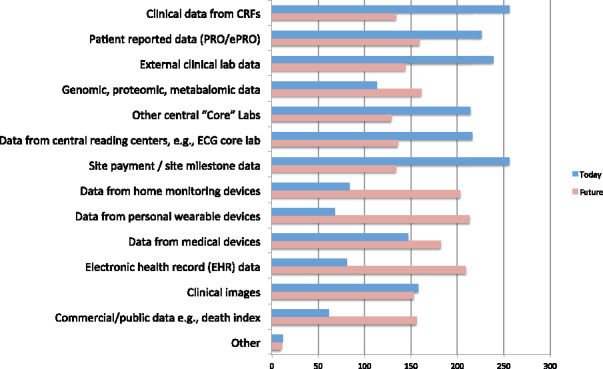

Clinical data management competencies

Of those who responded to the survey, 69% provided information about job tasks, 233 for early- to mid-career and 235 for mid- to late-career clinical research data managers (Figure 4). The average percent of effort spent on tasks was calculated over all those who provided this information. Differences in tasks were easily identified from differences in task distribution between early- to mid- and mid- to late-career data managers (top and bottom graphs in Figure 4). For example, the data processing tasks (tasks 27–45) were present, albeit at a low percent of effort, for early- to mid-career data managers and much less prevalent for later career data managers. Programming tasks (tasks 46–53) were present but not dominant in either group, while testing tasks (tasks 54–59) were more prominent for early- to mid-career data managers. As expected, personnel management tasks (tasks 60–62) were largely absent for early- to mid-career data managers and were reported with higher frequency by mid- to late-career data managers. Coordination and project management tasks (tasks 63–81) were much more frequent for mid- to late-career data managers and review tasks slightly more frequent in this group. None of the 91 competencies went unselected.

Figure 4.

Job tasks indicated by respondents.

Of the 3228 total responses for early- to mid-career tasks, there were 22 uncodable responses, ie, responses that could not be mapped to 1 of the 91 tasks. Two were clerical in nature (filing) and outside the scope of the profession, 3 were illegible, and the remaining 17 were not specific enough to map to 1 of the 91 tasks. No new tasks were identified from the uncodable responses. Of the 3798 responses for mid- to late-career tasks, there were 25 uncodable responses. Three of the 25 were illegible, and the remainder were either too specific and not mapped, or not specific enough to be mapped to 1 of the 91 tasks.

Ten possible future tasks were identified from question 8c, “Please list in your own words any new tasks, i.e., not listed on the facing page, that CDMs will be performing in the future” (Table 3). Although eSource is a type of data rather than a job task, it remains listed with the responses because of the high frequency with which it was mentioned.

Table 3.

Potential New Tasks Identified

| Potential New Task | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Risk-based monitoring | 30 |

| Data integration | 20 |

| eSource | 20 |

| Data visualization | 15 |

| Acquisition and management of electronic health record data | 12 |

| Technology awareness, adoption, management | 11 |

| Process improvement | 10 |

| Metadata management | 7 |

| Centralized monitoring | 7 |

| Data warehousing | 6 |

Foundational knowledge

Question 9 probed foundational knowledge necessary for performance of job tasks (Table 2). One foundational knowledge item, software development concepts, was crossed out by 48 respondents. The remainder of the items crossed out were marked by <10% of the respondents. Eight new foundational knowledge topics were identified by respondents (Table 4).

Table 4.

Potential Foundational Knowledge Identified

| New Foundational Knowledge Topic | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Informatics topics | 17 |

| Computer programming | 8 |

| Leadership and professional etiquette | 7 |

| Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium standards other than the submission data tabulation model and the lab model | 6 |

| Clinical knowledge | 6 |

| Risk-based decision-making | 4 |

| Metrics | 3 |

| International regulatory authorities and regulations | 1 |

DISCUSION

The survey was SCDM’s initial test of separating foundational knowledge, job tasks, and application context. In making these separations to create the survey, the study team found that the 3 categories were easily distinguishable, and they were pleased that the total number of competencies decreased to 91. Applying this new separation to the survey provided a test of the face validity of such an approach. The ease with which conference attendees were able to respond to the different categories supported the separate treatment.

The tasks can be further refined and reduced. For example, “data imputation” (task 32) requires a verb such as “perform” or a verb phrase such as “impute data” to comprise a task. The 3 items under training (tasks 24–26) describe who is being trained rather than actual tasks associated with training and would more appropriately be stated as 1 task, “Ascertain need for, develop and deliver training on data collection and management processes and systems.” Similarly, the 3 items under personnel management (tasks 60–62) describe the role being supervised rather than the tasks associated with personnel management and would more appropriately be stated “Assign and oversee the work of subordinates,” and would subsume review tasks 90 and 91.

Historically, clinical research data management has suffered from inaccurate perceptions, eg, that managing data for research studies mainly consists of handling paper forms and entering data. Given the scope of practice, this is certainly not the case. It is true that formal education programs are needed to better prepare the workforce as application contexts continue to expand and as methodologies for managing and using data to organizational advantage continue to advance. As the profession better articulates necessary competencies and foundational knowledge, degree programs can be developed to meet the growing workforce need.

Although job task surveys have been conducted in previous years, the work reported here is the most formal, eg, job tasks subjected to semantic work and competencies separated along the lines of prevailing educational theory. With the survey having been subjected to semantic work, 3 rounds of membership surveying, and 12 years of testing through the professional certification exam, we are confident in articulating the competency domains and competencies reported here as the scope of professional practice in clinical research data management. While the scope of practice is more narrow than the entire field of CRI, we recognize CRI and more broadly biomedical informatics as the science upon which the majority of the clinical research data management profession is based. Reliance on such a relevant and vibrantly productive scientific discipline makes for a bright professional future. In collaboration with CRI researchers, operational challenges and problems can be posed and systematically probed, and promising results can be translated into operational practice, a process from which new innovations and research needs will spring.

Limitations

Administering the survey at a professional society meeting limits interpretation of the data to what applies to conference attendees. Given the use of multiple approaches throughout the years, eg, surveys at annual conferences, web-based surveys distributed to members, and the professional certification exam itself, the competencies have been subjected to well over 1000 respondents. The long-term probing of the competencies across multiple contexts mitigates this limitation.

Although changing, the membership of the SCDM has primarily consisted of individuals from the therapeutic development industry. Unfortunately, because of the low proportion of respondents from academia, we cannot claim generalizability to that important segment of the clinical research data management community. We can confirm that responses from academic respondents did not differ significantly from those from industry respondents. While research studies, systems, and resources can differ between academically oriented studies and those conducted by industry, the best practices to assure appropriate quality and consistency of data are based in common principles, eg, traceability, replicability, and reproducibility, and thus at some core level are fundamentally the same.

CONCLUSIONS

The survey reported here reaffirmed and refined the scope of practice of clinical research data management. Clearer articulation of foundational knowledge and professional competencies has helped to better ground the profession in supporting scientific disciplines. The competency survey reported here will serve as the foundation for the upcoming revision of the CCDMTM exam and is offered as a resource to inform development and maintenance of formal education programs supporting the profession.

Funding

The work reported here received support from Duke University’s institutional commitment to grant R00-LM011128, which was funded by the National Library of Medicine, a component of the National Institutes of Health. The opinions expressed here belong solely to the authors and are not necessarily representative of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Contributors

MNZ: Led the study group and drafted initial versions of data collection form and manuscript, administered survey and collected survey responses, oversaw data management.

AL: Participated in the design of the study and data collection form.

LS: Participated in the design of the study and data collection form, administered survey, and collected survey responses.

TB: Participated in the design of the study, research protocol, and data collection form.

SK: Participated in the design of the study, research protocol, and data collection form.

PZ: Participated in the design of the study and data collection form, administered survey, and collected survey responses.

SK: Participated in the design of the study and data collection form.

DJ: Participated in the design of the study, research protocol, and data collection form and secured permission and resources to support conducting the study.

DP: Participated in the design of the study and data collection form, administered survey and collected survey responses, vetted preliminary results (peer review) with the SCDM Board of Trustees.

DZ: Participated in the design of the study and data collection form, vetted preliminary results (peer review) with the SCDM Board of Trustees and Leadership Conference.

TW: Reviewed competencies and contributed to the sections of the manuscript explaining underlying educational theory.

CP: Conducted statistical analysis, contributed significantly to interpretation of the results.

All authors reviewed and commented on multiple versions of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Clairellen Miller, MHA, who entered the survey data; Mary Williams, BS, who performed verification of the entered data; and Hannah Andrews, Lindsay Emow, and Monique Cipolla, who provided administrative support to the study team. Further, the work presented here rests on the foundation of the initial task list led by Susan Bornstein, MPH; the Good Clinical Data Management Practices practice standard initiated by Kaye H Fendt, MSPH; and the initial version of the professional certification exam led by Armelde Pitre, MBA.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

References

- 1. McBride R, Singer SW, Introduction [to the 1995 Clinical Data Management Special Issue of Controlled Clinical Trials]. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1995;16:1S–3S. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Society for Clinical Data Management . Good Clinical Data Management Practices (GCDMP), October 2013. http://www.scdm.org. Accessed January 20, 2017.

- 3. Bloom BS, Krathwohl DR. Taxonomy of educational objectives: the classification of educational goals, by a committee of college and university examiners. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. New York, NY: Longmans, Green; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson LW, Krathwohl DR, Airasian PW, Cruikshank KA, Mayer RE, Pintrich PR et al., eds. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;63:9s. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Organization, Review, and Administration of Cooperative Studies (Greenberg Report): A Report from the Heart Special Project Committee to the National Advisory Heart Council, May 1967. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1988;9:137–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Collen MF. Clinical research databases: a historical review. J Med Sys. 1990;14:06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McBride R, Singer SW, Interim reports, participant closeout, and study archives. Con Clin Trials. 1995;16:1S–3S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gassman JJ, Owen WW, Kuntz TE, Martin JP, Amoroso WP. Data quality assurance, monitoring, and reporting. Cont Clin Trials. 1995;16:1S–3S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hosking JD, Newhouse MM, Bagniewska A, Hawkins BS. Data collection and transcription. Cont Clin Trials. 1995;16:1S–3S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McFadden ET, LoPresti F, Bailey LR, Clarke E, Wilkins PC. Approaches to data management. Cont Clin Trials. 1995;16:1S–3S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blumenstein BA, James KE, Lind BK, Mitchell HE. Functions and organization of coordinating centers for multicenter studies. Cont Clin Trials. 1995;16:1S–3S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clinical Data Management Special Issue of Controlled Clinical Trials, Appendix C: Reviewers for this issue. Cont Clin Trials. 1995;16:1S–3S. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clinical Data Management Special Issue of Controlled Clinical Trials, Appendix B: Studies cited and sources of information. Cont Clin Trials. 1995;16:1S–3S. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ittenbach R, Howard K, Nahm M. Training the next generation of clinical data managers: the industry/academia interface. Society for Clinical Data Management (SCDM) Annual Conference, September 10–13, 2013, Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bornstein S. Clinical data management task list. Data Basics. 1999;5:8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Society for Clinical Data Management . Appendix 4 to the CCDM Certification Handbook. Last modified May 7, 2007. http://www.scdm.org. Accessed June 1, 2015.

- 18. Nahm M, Zhang J. Operationalization of the UFuRT methodology for usability analysis in the clinical research data management domain. J Biomed Inform. 2009;422:327–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nahm M, Johnson C, Walden A, Johnson T, Zhang J. Clinical research data management tasks and definitions. Poster presented at the AMIA Summits Transl Sci. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wand Y, Weber R. On the ontological expressiveness of information systems analysis and design grammars. Inf Syst J. 1993;34:217–37. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.