Abstract

Background

The importance of vasopressin and/or urine concentration in various kidney, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases has been emphasized recently. Due to technical constraints, urine osmolality (Uosm), a direct reflect of urinary concentrating activity, is rarely measured in epidemiologic studies.

Methods

We analyzed two possible surrogates of Uosm in 4 large population-based cohorts (total n=4,247) and in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD, n=146). An estimated Uosm (eUosm) based on the concentrations of sodium, potassium and urea, and a urine concentrating index (UCI) based on the ratio of creatinine concentrations in urine and plasma were compared to the measured Uosm (mUosm).

Results

eUosm is an excellent surrogate of mUosm, with a highly significant linear relationship and values within 5% of mUosm (r=0.99 or 0.98 in each population cohort). Bland-Altman plots show a good agreement between eUosm and mUosm with mean differences between the two variables within ±24 mmol/L. This was verified in men and women, in day and night samples, and in CKD patients. The relationship of UCI with mUosm is also significant but is not linear and exhibits more dispersed values. Moreover, the latter index is no longer representative of mUosm in patients with CKD as it declines much more quickly with declining GFR than mUosm.

Conclusion

The eUosm is a valid marker of urine concentration in population-based and CKD cohorts. The UCI can provide an estimate of urine concentration when no other measurement is available, but should be used only in subjects with normal renal function.

Keywords: Sodium, Potassium, Urea, Circadian rhythm, Water balance, Chronic kidney disease

Introduction

The interest in the influence of the antidiuretic hormone vasopressin (ADH or AVP) as a significant player in various kidney, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases has been revived recently [1–4]. The availability of non-peptide, orally active selective vasopressin receptor antagonists (vaptans) [5, 6] and of a reliable ELISA for the measurement of copeptin, a validated surrogate of vasopressin [7, 8], has opened the door for a number of studies addressing the vasopressin/thirst pathway and osmoregulation in general (see review in [9]).

Independent of the well-known contribution of ADH to various forms of water disorders, recent epidemiological studies have shown significant associations between indices of the vasopressin/hydration system and the incidence or progression of diseases including chronic kidney disease (CKD), autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), diabetic nephropathy, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and insulin resistance [10–14, 4, 15–21]. A number of experimental studies have demonstrated the adverse effects of vasopressin or a low level of hydration in animal models of these disorders [22, 10, 23–26]. A recent double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, using a selective vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist, tolvaptan, proved to bring significant benefit over a 3 year period in patients with ADPKD and well preserved renal function [27].

Because AVP is difficult to measure due to its small mass, very low circulating concentrations, poor stability in vitro, and time-consuming assay, most of the recent studies dealing with this hormone rely on the measurement of copeptin (a peptide that is part of the pre-pro-hormone containing vasopressin) in plasma or, more indirectly, on fluid intake or daily urine volume [28, 29]. Urine osmolarity (Uosm), the most direct parameter reflecting the action of AVP on distal tubular segments of the kidney, is rarely measured due to technical constraints, and is thus usually not available in epidemiologic studies.

Various surrogates of Uosm have been used in clinical studies. They include the specific urine density or the refraction index that give only an approximate value of the solute content in the urine and are subjected to several biases including distorsion in the case of proteinuria and poor precision of readings. Two other surrogates are the Urine Concentrating Index (UCI) based on the handling of creatinine by the kidney [30, 31], and the estimated urine osmolarity (eUosm) based on the concentration of the three main osmoles present in the urine: sodium, potassium and urea [31, 32]. To our knowledge, the validity of these two surrogates has not been evaluated in large, population-based cohorts with normal or altered renal function. The aim of the present study was to assess the value of eUosm and UCI compared to measured Uosm (mUosm) in large population-based and CKD cohorts, and to test the influence of sample type, gender and age on these markers.

Subjects and Methods

Cohorts

The general characteristics of the subjects belonging to the different cohorts are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information about the different cohorts

| Cohort | CROATIA-Korcula | GS:SFHS Aberdeen |

GS:SFHS Glasgow |

SKIPOGH Day |

SKIPOGH Night |

CKD Necker |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 463 | 554 | 2305 | 925 | idem | 146 |

| Sample type | Spot | Spot | Spot | Day period | Night period | 24 h |

| Age, y | 58 (19 – 87) | 57 (19 - 88) | 53 (18 - 93) | 47 (18 - 90) | idem | 64 (17 - 86) |

| Gender : M / W, % | 41 / 59 | 43 / 57 | 41 / 59 | 47 / 53 | idem | 59 / 41 |

| BMI | 27.97 ± 0.21 | 27.22 ± 0.22 | 26.97 ± 0.21 | 25.03 ± 0.15 | idem | 24.16 ± 0.30 |

| mUosm, mosm/kg H2O | 668 ± 10 | 524 ± 10 | 540 ± 5 | 457 (110 – 1174) | 541 (67 – 1304) | 396 ± 13 |

| eUosm, mosm/L | 664 ± 9 | 526 ±11 | 547 ±5 | 450 (118 – 1142) | 513 (61 – 1223) | 381 ± 12 |

| UCI | 165 ± 4 | 119 ± 3 | 117 ± 2 | 114 ± 2 | 145 ± 3 | 41.6 ± 3.6 |

| Uurea, mmol/L | 285 ± 5 | 225 ± 5 | 250 ± 3 | 227 ± 4 | 296 ± 5 | 177 ± 6 |

| UNa, mmol/L | 113.8 ± 2.2 | 79.3 ± 2.0 | 83.9 ± 1.0 | 94.8 ± 1.6 | 93.4 ± 1.6 | 68.7 ± 2.8 |

| UK, mmol/L | 65.9 ± 1.6 | 63.5 ± 1.5 | 64.9 ± 0.8 | 47.4 ± 0.8 | 32.7 ± 0.6 | 33.3 ± 1.3 |

| eGFR . ml/min/1.73 m2 | 83.4 ± 1.1 | 92.2 ± 0.7 | 89.1 ± 0.4 | 96.3 ± 0.6 | — | 46.2 ± 2.5 |

Means + SEM or median (interval).

1. Generation Scotland: SFHS (GS:SFHS) and CROATIA-Korcula

Aberdeen and Glasgow subjects were selected from the Generation Scotland study, a family-based genetic epidemiology study that included 24,000 volunteers from across Scotland, as previously described [33]. Biological samples including morning spot urine were collected during participation from 2006-2011 [34]. We also studied subjects from the CROATIA-Korcula cohort, a family-based, cross-sectional study from the island of Korcula (Croatia) that initially included 965 subjects, as previously described [35]. Studies of these three cohorts included clinical information, biochemical measurements, and lifestyle and health questionnaires. For the present study, subjects from these three cohorts were randomly selected for measurement of Uosm (n=554 from GS:SFHS Aberdeen, 2305 from GS:SFHS Glasgow and 463 from CROATIA-Korcula). All participants provided written informed consent. For GS:SFHS national ethical approval has been obtained from the National Health Service Tayside Research Ethics committee. The CROATIA-Korcula study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Medical School, University of Zagreb.

2. SKIPOGH

SKIPOGH (Swiss Kidney Project on Genes in Hypertension) is a family- and population-based cross-sectional multi-center study that examines the genetic determinants of blood pressure. Participants were recruited in 2009-2013 in the cantons of Bern and Geneva, and the city of Lausanne. Detailed methods have been previously described [36, 37]. The study visit was performed in the morning after an overnight fast. Participants were asked to bring urine of the previous 24 h collected separately during day and night periods defined according to each participant’s self-reported bedtime and wake-up time. The SKIPOGH study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne (Lausanne, Switzerland), by the Ethics Committee for the Research on Human Beings of Geneva University Hospitals (Geneva, Switzerland), and by the Ethics Committee of the Canton of Bern, (Bern, Switzerland).

3. CKD patients

This study includes 146 out-patients with CKD of diverse etiologies and various levels of renal dysfunction, attending the Nephrology Department of Necker Hospital (Paris, France) in 1993 for a bi-annual checkup [38, 19]. All patients provided 24-h urine. Informed consent was obtained for storage of the samples and additional future measurements to enable a more complete understanding of the pathophysiological characteristics related to CKD. On the freshly collected plasma and urine samples, osmolality was measured with a freezing point osmometer (Roebling, Berlin, Germany). Creatinine concentration was measured by the Jaffe colorimetric method and creatinine clearance in ml per 1.73 m2 was used as an estimate of GFR. Concentration of urinary solutes was measured with a classical automatic multianalyzer.

Measurements in Plasma and Urine Samples

In the 4 population-based cohorts, urine samples were kept frozen at -80°C until measurements of Uosm and urinary solute concentrations. Sodium, potassium, glucose, creatinine, and urea were measured with a Beckman Coulter Synchron System Assays (Unicell DxC Synchron Clinical System). The CKD-EPI formula was used to calculate eGFR [39]. Uosm was measured on 20 µl samples by the freezing-point depression technique using an Advanced Osmometer (Massachusetts 02062, USA). A control (Clinitrol 290) and a set of calibration standards (50, 850 and 2000 mosm/kg H2O) were used before running each batch. The intra-assay coefficient of variability was 0.19 % and the inter-assay coefficient of variability was 1.32 %.

Calculations and Statistical Analyses

Most modern osmometers measure the osmolality of the fluids in milliosmoles per kg water (mosm/kg H2O) (see footnote 1). Osmolarity expresses the concentration of osmotically active molecules in milliosmoles per liter of water (mosm/L). Sweeny and Beuchat described the technical aspects and limitations of osmometry methods and provided detailed considerations about the concepts of osmotic pressure, osmolarity, osmolality, and solute concentrations [40].

Estimated urine osmolarity (eUosm)

The major urinary solutes, accounting for more than 90% of all urinary osmoles, are urea and the two cations sodium and potassium along with their accompanying anions. Thus, their cumulated concentrations (in mmol/L) should be close to the actual Uosm (in mosm/L). An "estimated" Uosm can be calculated according to the following formula:

where UNa, UK and Uurea are the urinary concentrations of sodium, potassium and urea, respectively, in mmol/L. (UNa + UK) is multiplied by 2 to account for the accompanying anions. If urea was measured as urea nitrogen, it should be remembered that there are two atoms of nitrogen (MW = 14) per molecule of urea. Urea in mmol/L = urea nitrogen in mg/dL x 0.357 (explanation: urea nitrogen in mg/dL multiplied by 10 [conversion of dL to L] and divided by 14x2 [mg N per mmol urea]. In case of significant glycosuria, glucose concentration can be added to the formula.

Urine Concentrating Index (UCI)

Creatinine is freely filtered and is assumed to undergo negligible secretion or reabsorption along the nephron when kidney function is normal. Thus, the concentration of creatinine in urine relative to that in plasma (Ucreat and Pcreat, respectively), i.e., the ratio of urine-to-plasma creatinine concentrations, is proportional to the fraction of filtered water that has been reabsorbed to concentrate the solutes in the urine. This ratio provides an Index of Urine Concentration (UCI), a ratio that has no unit:

Statistical analyses

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 19 (IBM Corporation, New York) and GraphPad Prism 5 were used to carry out the statistical analyses and generate the figures. Results are shown as means ± SEM for normally distributed variables, or as medians and 25%-75% interquartile range (IQR) for other variables. The agreement between mUosm and eUosm was assessed by Bland-Altman plots. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the distribution of mUosm in the SKIPOGH study. Correlations were studied using Pearson's correlation analysis (in case of normality) or Spearman’s rho test (for other variables). Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare repeated measures for day and night urine samples of the SKIPOGH subjects. The significance level was set at 5 %.

Results

1. Uosm surrogates in population-based cohorts

Large variations in urine concentration are observed among individuals. The mUosm in different subjects varies from ≈ 150 to 1,200 mosm/kg H2O in spot urine of the three population-based cohorts as well as in day and night urine of the SKIPOGH cohort (Figures 1A and 2B). A substantial number of subjects (21 %) dilute their urine below plasma osmolality whereas others (9 %) concentrate their urine up to three times more than the level of plasma osmolality (Figure 2A). These extreme mUosm are not associated with differences in eGFR.

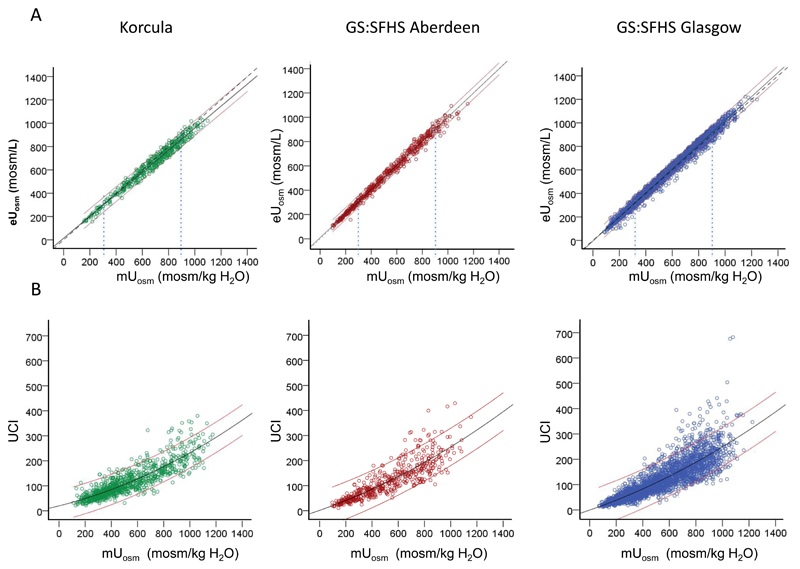

Figure 1.

Comparison of urine osmolality surrogates with measured urine osmolality. A. Linear correlation between measured osmolality and estimated osmolarity in 3 cohorts. CROATIA-Korcula: mUosm = 1.03 eUosm + 3.3 (p<0.001, r = 0.98); GS:SFHS Aberdeen: mUosm = 0.99 eUosm – 4.4 (p<0.001, r = 0.98); GS:SFHS Glasgow:. mUosm = 0.96 eUosm + 11 (p<0.001, r = 0.99). The thin vertical lines show mUosm of 300 and 900 mosm/kg H2O, i.e. approximatively one time and three times the plasma osmolality. B. Quadratic correlation between UCI and measured urine osmolality in 3 cohorts. CROATIA- Korcula: mUosm = 5.04 UCI – 0.009 UCI2 + 126 (p<0.001, r = 0.76); GS:SFHS Aberdeen: mUosm = 5.52 UCI – 0.009 UCI2 + 28 (p<0.001, r = 0.90); GS:SFHS Glasgow: mUosm = 4.89 UCI – 0.006 UCI2 + 90 (p<0.001, r = 0.89). Black lines represent the best-fit curves. Red thin lines represent the 95% confidence intervals. Dotted lines in the top panel represent the medians.

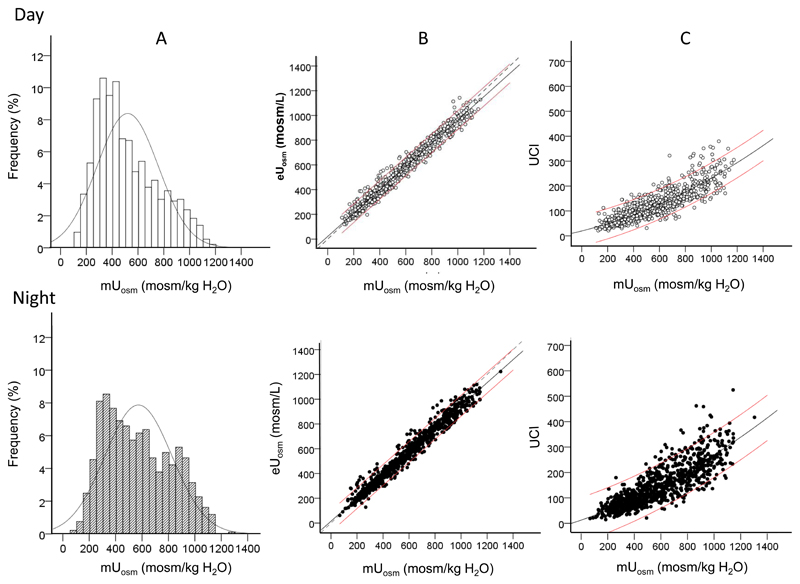

Figure 2.

Daytime and night-time urine in the SKIPOGH population (n= 925). A. Distribution of mUosm among SKIPOGH subjects. Thin curves represent the normal distribution model. B. Linear correlation between measured and estimated Uosm in daytime and night-time urine. C. Quadratic correlation between UCI and mUosm in daytime versus night-time urine. In B and C, black lines represent the best-fit curves and red thin lines 95% confidence intervals. Dotted lines in B represent the medians.

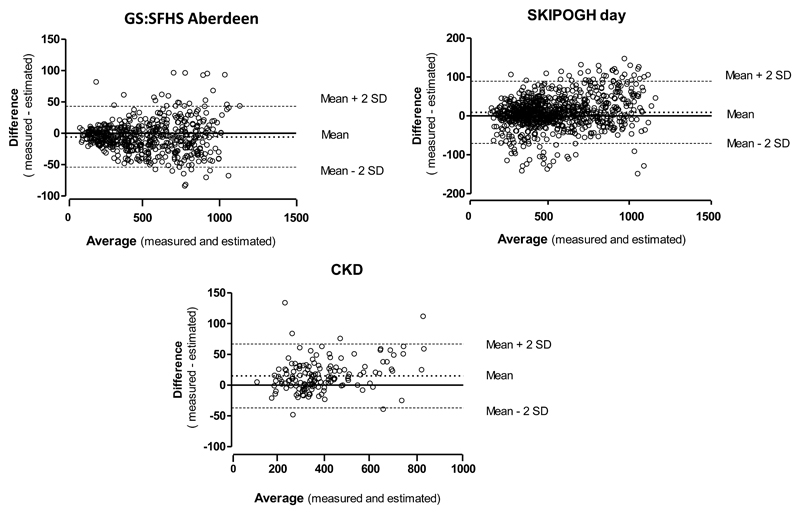

Highly significant linear correlations are observed between mUosm and eUosm in all populations (CROATIA-Korcula r=0.98,GS:SFHS Aberdeen r=0.98, GS:SFHS Glasgow r=0.99) (Figures 1A and 2B). The best fit linear regression lines are almost superimposed with the medians. Bland-Altman plots show a good agreement between eUosm and mUosm in the three population based cohorts(Supplementary Table 1). This is reflected in the small bias values (CROATIA-Korcula bias=24, GS:SFHS Aberdeen bias= -6, GS:SFHS Glasgow bias= -23), and relatively narrow precision range (CROATIA-Korcula -44 to 90, GS:SFHS Aberdeen -54 to 43, GS:SFHS Glasgow -80 to 34). Plot for the GS:SFHS Aberdeen population is given as an example in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Bland-Altman plots showing the agreement between estimated and measured Uosm in the spot urine samples of GS:SFHS Aberdeen (top), the day urine samples of SKIPOGH (middle) and the 24-h urine of the CKD patients.

Although the relations between UCI and mUosm are significant, they exhibit a relatively large dispersion of individual values, increasing with increasing osmolality (Figures 1B and 2C). Nonetheless, as an average, the ratio of UCI to mUosm is fairly constant (0.20, 0.21 and 0.22 for mUosm = 300, 600 and 900 mosm/kg H2O, respectively). UCI can be approximately converted to osmolality by the following quadratic formula : mUosm = 5 UCI – 0.007 UCI2 + 83.

The possible influence of glycosuria that occured in some subjects on eUosm was evaluated. Among 3322 subjects of the three cohorts in which urinary glucose was available, 58 exhibited glucosuria > 1.66 mmol/L [41] (mean ± SEM 11.58 ± 2.28 mmol/L; range 1.7 to 86.8). Their age and eGFR were 57.0 ± 1.8 y and 86.8 ± 2.4 ml/min.1.73 m2, respectively. Measured Uosm in these subjects was 642 ± 32 mosm/kg H2O. Estimated Uosm, calculated without or with the addition of urinary glucose was 624 ± 31 and 635 ± 32 mosm/L respectively, both within 3% of mUosm.

Urine osmolality is known to be higher in men than in women. This was verified in the cohorts of the present study (Supplementary Table 2): men exhibited higher mUosm and eUosm than women although the magnitude of this gender difference differed among the three populations. eUosm was very close to mUosm in both genders and the men/women ratio of eUosm was very similar to that for mUosm. For UCI, there was a tendency for more inter-individual variation in women than in men as well as lower men/women ratios which tended to underestimate the gender difference (Supplementary Table 2).

2. Uosm surrogates in day and night urine

In healthy subjects, urine is usually more concentrated during the night than during the day. We investigated if the relationships between mUosm, eUosm and UCI are comparable in day and night urine of the 925 subjects of the SKIPOGH study (Figure 2A). The Shapiro-Wilk test indicates that these variables diverge from a normal distribution (shown by a thin curve). Mean mUosm ± SEM during day and night was respectively 520 ± 4 and 572 ± 7 mosm/kg H2O. Median [IQR] values were 457 [334-676] and 541 [356-777] mosm/kg H2O, respectively (p <0.001, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). The histograms of mUosm during day and night do not follow a normal distribution and there is a tendency for a bimodal distribution during the night.

Measured and estimated Uosm values exhibit highly significant linear correlations in both day and night urine (Figure 2B), as also observed in the spot urine of the other cohorts. Bland-Altman plots show a good agreement between eUosm and mUosm in day and night urine, as reflected by the small bias values (day bias=9, night bias= 24), and the precision range (day -71 to 89, night -66 to 114) (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 1). The relations between UCI and mUosm are best described by quadratic correlations. Thin red lines show the 95% confidence intervals. As in the three cohorts shown in Figure 1, UCI vs mUosm values were more widely dispersed than eUosm vs mUosm values.

3. Uosm surrogates in CKD patients

Table 2 compares the values of eUosm and UCI to those of mUosm in CKD patients, according to their level of renal function. In all CKD classes, eUosm is very close to mUosm. Both variables decline in parallel with declining eGFR. Bland-Altman plot show a relatively good agreement between the two methods, as reflected by the small bias value (15) and the precision range (-37 to 67) (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 1). In contrast, UCI declines much more dramatically than mUosm. These differences are due mostly to the progressive rise in plasma creatinine concentration (from 91 ± 5 to 514 ± 34 µmol/L in the two extreme classes, a 5.6 fold increase) while urine creatinine concentration declines only two-fold as a result of a lower total creatinine excretion and a moderately higher 24-h urine volume. In these patients, a spot urine sample was collected in the morning following the 24-h urine collection. (Table 2). mUosm in morning urine is 10-20 % higher than mUosm in 24-h urine, a difference that seems independent of the level of renal function.

Table 2.

Osmolality and its surrogates in 147 CKD patients according to the level of renal function

| CKD Stage | N | Creatinine Excretion mmol/d |

Spot mUosm mosm/kg H2O |

mUosm mosm/kg H2O |

eUosm mosm/L |

eUosm / mUosm | UCI (Ucreat/Pcreat) |

UCI*100 / mUosm (1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 (>90) | 13 | 13.4 ± 1.0 | 738 ± 61 | 650 ± 48 | 608 ± 43 | 0.94 ± 0.01 | 146 ± 17 | 22.1 ± 1.6 |

| Stage 2 (60-89) | 29 | 13.2 ± 0.7 | 517 ± 32 | 479 ± 34 | 458 ± 34 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | 59 ± 5 | 12.3 ± 0.4 |

| Stage 3 (30-59) | 54 | 11.5 ± 0.5 | 450 ± 14 | 371 ± 14 | 358 ± 14 | 0.97 ± 0.01 | 34 ± 2 | 9.2 ± 0.3 |

| Stage 4 (15-29) | 32 | 9.4 ± 0.5 | 376 ± 13 | 321 ± 13 | 311 ± 12 | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 17 ± 1 | 5.2 ± 0.3 |

| Stage 5 (<15) | 19 | 8.1 ± 0.5 | 318 ± 11 | 296 ± 12 | 291 ± 12 | 0.98 ± 0.02 | 7 ± 1 | 2.5 ± 0.2 |

Means ± SEM.

CKD stages are shown with the limits of eGFR in ml/min per 1.73 m2.

Spot mUosm = mUosm of a morning spot urine sample. All other values concern 24-h urine collection.

For the ratio of UCI/mUosm. UCI was multiplied by 100 to make the reading easier.

Discussion

The urine concentrating activity of the human kidney was rarely investigated, except in a few conditions such as urolithiasis and diabetes insipidus. Recent experimental and epidemiological findings have renewed the interest in the components of the water balance and in the parameters reflecting this integrative function [22, 24, 1, 28, 29, 9, 4, 42, 32, 43, 18]. It is indeed quite different for the kidney to excrete a daily osmolar load of 900 mosm in 1 liter of urine at 900 mosm/L or in 3 liters of urine at 300 mosm/L. Increased urine concentration (associated with increased solute-free water reabsorption) results in a lower fractional excretion of several solutes and in a significant hyperfiltration that is, at least in part, mediated by vasopressin acting on renal V2 receptors. It has been proposed that this hyperfiltration is mediated by changes in the composition of the tubular fluid at the macula densa, resulting from vasopressin's action on water, sodium and urea transport in the collecting duct and the resulting recycling of urea in the medulla (see review in [9]). Uosm, the most direct reflect of the urine concentrating activity, is rarely measured in large cohorts because of technical issues (see below). The present study, in a cross-sectional design, describes two practical, easily accessible surrogates of Uosm and assesses their validity by comparing the results to the actually measured Uosm in large cohorts of the population and in a group of patients with CKD. We also checked the value of these surrogates in various sample types (spot or 24-h, day and night), and according to gender and to renal function.

Our results show that the estimated Uosm, based on sodium, potassium and urea concentrations, is an excellent surrogate of the measured Uosm. In most cases, eUosm is within ± 5 % of mUosm. This is similarly true in men and women, as well as in urine collected during day or night, and in patients with impaired renal function at any level of GFR. One may wonder how eUosm and mUosm may be so close when the formula used for the calculation of eUosm neglects the minor solutes that should however represent more than 5 % of all urinary solutes. This is partly explained by the fact that the units are not the same. eUosm is expressed in mosm/L while mUosm is in mosm/kg H2O. Because one liter of water with dissolved solutes weights more than 1 kg, the osmolality is lower than the osmolarity. The two measures differ only modestly for solutions within the biological range. For example, a solution containing 140 mmol/L NaCl and 500 mmol/L urea has an osmolarity of 780 mosm/L and an osmolality of 751 mosm/kg H2O (i.e. 3.7 % lower). This difference partially compensates for the missing solutes and thus contributes to the almost equality of eUosm and mUosm. Another factor is that electrolytes are assumed to be totally dissociated in the eUosm formula. Although the dissociation is high in solutions within the physiological range, it is less than 100%, thus also contributing to modestly overestimate eUosm.

UCI is a less accurate reflection of mUosm than eUosm because creatinine is known to undergo some secretion as well as some reabsorption along the tubule. The net result of these opposite effects depends on the rate of urine flow [44]. Our study shows that individual values are fairly dispersed and the correlations between the two variables are not linear. However, when no other approach is available, UCI remains a possible surrogate of urine concentration, provided it is applied to subjects with normal renal function. As clearly demonstrated in the present study, UCI diverges markedly from mUosm in patients with CKD – limiting its use when renal function is impaired and probably also when abnormal handling of creatinine or excessive 24-h intake of creatine are suspected.

A few alternative methods for quantifying urine concentration have been used. Urine density (UD) (or specific gravity) may be evaluated in 7 colored grades with commercially available dipsticks (Labtix 8SG and Multistix 8SG AMES/Bayer Diagnostics) or evaluated by refractometry using a hand-held refractometer (Pen Urine S.G., Atago, Tokyo, Japan) [45]. In the D.E.S.I.R. study (a cohort of the French population), UD was measured with dipsticks in fresh spot morning urine samples from 1604 subjects, and eUosm was calculated (same formula as here) [8]. Median [IQR] eUosm was 664 [272] mosm/L. UD was well correlated with eUosm (r = 0.446, P < 0.00001). Another studie showed that UD was well correlated with measured Uosm but the wide dispersion made it "impossible to use UD as a dependable clinical estimate of Uosm" [46]. Moreover, UD or specific gravity cannot be used if urine contains proteins or glucose [47].

It is important to note that Uosm varies greatly among different subjects, as shown in the four populations of the present study and in a few previous reports [31, 42]. In usual conditions, some subjects produce hypo-osmotic urine while others show Uosm up to 1200 mosm/kg H2O. This wide range of spontaneous Uosm is possibly due to large inter-individual variations in the daily solute load [48], in fluid intake [42], and in thresholds for vasopressin secretion and/or thirst that are, in part, genetically determined [49]. Both vasopressin concentration and urine osmolarity are known to differ between sexes. Men have higher vasopressin/copeptin levels [50, 18, 21] and higher Uosm than women [31]. This difference is mostly due to the fact that men excrete a larger osmolar load than women with a higher urine osmolality but an approximatively similar 24-h urine volume [31, 51]. Therefore, in studies using these variables, data for the two sexes are often presented separately. We verified here the validity of the two surrogates in each gender. For both genders, the relation between eUosm and mUosm is highly significant and the regression line between these two variables is very close to the identity line. The UCI also reflected this gender difference but tended to underestimate it slightly, possibly because of the known difference in creatinine handling in men and women.

Differences in the usual urine concentration may be associated with the ethnic background. A few studies showed that African Americans tend to concentrate urine about 20% more than Caucasians and have higher vasopressin levels [52, 30, 53]. To our knowledge, very few studies have evaluated other possible differences in usual urine concentration related to habitat or ethnic background [54–58].

The results of the SKIPOGH study illustrate the fact that urine is usually on the average more concentrated during the night than during the day by about 50-100 mosm/kg H2O. Few studies have investigated day and night urine separately [59–61]. They showed that the circadian pattern of urine flow rate/urine concentration and/or sodium excretion rate may be disturbed in some subjects. An excessive urine concentration during daytime, limiting sodium and/or water excretion rate, is subsequently compensated at night by the pressure-natriuresis mechanism [62, 59–61, 63]. Accordingly, measurement of urine osmolality in overnight urine samples may not be representative of 24-h urine.

There are several advantages for using surrogates of urine osmolality. Osmometers, based on either freezing point depression or vapor pressure methods, are expensive and rarely equipped with automatic sample changers. Each measurement lasts a minute or two (due to the time needed to freeze or heat the sample, respectively), thus allowing some evaporation if samples are loaded in the changer in advance. We tested the automatic changer and observed that mUosm values in the same sample increased after 10 loads. In studies involving a large number of subjects in which individual measurements are practically impossible, values may increase artifactually depending on the timing of the measurements. Moreover osmolality measurements cannot be coupled with measurements of various solutes performed by automatic analyzers; they thus require separate aliquots and time-consuming manipulations. The excellent correlation between eUosm and mUosm, over the whole range of mUosm values, even in CKD, validate eUosm as an appropriate surrogate of mUosm, especially in large cohorts.

Urine electrolytes are often available in epidemiological studies, but urea, needed for the calculation of eUosm, is less frequently measured. When new measurements are initiated on previously stored samples in order to evaluate the kidney's concentrating activity, authors should consider the respective advantages of measuring either osmolality or urea concentration. Urea is much easier, quicker and cheaper to measure than osmolality. Moreover, it will also provide data for a significant solute in the urinary concentrating process, and allow an indirect evaluation of protein intake.

This study has some limitations. It concerns exclusively subjects of European descent. Studies in subjects of other ethnic backgrounds are required. The possible influence of socio-demographic factors has not been considered. However, we think it is reasonable to assume that the highly significant correlations between eUosm and mUosm, and the relatively good relationships of UCI with mUosm are not dependent upon the population under study and may be extended to all populations, as long as the measurements of sodium, potassium, urea and creatinine concentrations are performed in appropriately equipped laboratory with rigorous methods.

In summary, the present study validates, in large cohorts, the use of an "estimated osmolarity", based on the measurement of sodium, potassium and urea, as an excellent surrogate of the measured urine osmolality. It also shows that the "urine concentrating index", based on the ratio of creatinine concentrations in plasma and urine, may be used as a relative index of urine concentration only in subjects with normal renal function because of the disturbed handling of creatinine in CKD. In contrast, eUosm is valid whatever the level of renal function. In future epidemiologic studies addressing the influence of vasopressin and urinary concentrating activity, the use of the "estimated urine osmolarity" should be recommended when the actual urine osmolality cannot be measured.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The SKIPOGH study is supported by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (FN 33CM30-124087). Other funding sources for this study include the European Commission Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013 under Grant 246539 of the Marie Curie Actions Programme and Grant 305608 of the EURenOmics project), Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique and Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique Medicale, and the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant 310030-146490, 32003B-149309 and the NCCR Kidney.CH program). Generation Scotland:SFHS received core funding from the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorate CZD/16/6 and the Scottish Funding Council HR03006.

The CROATIA-Korcula study on the Croatian island of Korcula was supported through the grants from the Medical Research Council UK and Ministry of Science, Education and Sport of the Republic of Croatia to I.R. (number 108-1080315-0302).

Footnotes

Footnote 1: The terms osmolarity or osmolality should be prefered to "osmotic pressure" because this physical osmotic force is not a pressure. It was named in this way in the past, when osmolarity was evaluated indirectly as a hydrostatic pressure generated by an unknown fluid opposed to a reference fluid, separated by a semipermeable membrane. The measurements were expressed in mm height between the levels of the two fluids in the two compartments.

Conflict of Interest : None of the authors have conflicts of interest to declare

References

- 1.Torres VE. Vasopressin in chronic kidney disease: an elephant in the room? Kidney Int. 2009;76(9):925–8. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolignano D, Zoccali C. Vasopressin beyond water: implications for renal diseases. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2010;19(5):499–504. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32833d35cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cirillo M. Determinants of kidney dysfunction: is vasopressin a new player in the arena? Kidney Int. 2010;77(1):5–6. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devuyst O, Torres VE. Osmoregulation, vasopressin, and cAMP signaling in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2013;22(4):459–70. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283621510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg A, Verbalis JG. Vasopressin receptor antagonists. Kidney Int. 2006;69(12):2124–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decaux G, Soupart A, Vassart G. Non-peptide arginine-vasopressin antagonists: the vaptans. Lancet. 2008;371(9624):1624–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60695-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgenthaler NG. Copeptin: a biomarker of cardiovascular and renal function. Congest Heart Fail. 2010;16(Suppl 1):S37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2010.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roussel R, Fezeu L, Marre M, Velho G, Fumeron F, Jungers P, Lantieri O, Balkau B, Bouby N, Bankir L, Bichet DG. Comparison between copeptin and vasopressin in a population from the community and in people with chronic kidney disease. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2014;99(12):4656–63. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bankir L, Bouby N, Ritz E. Vasopressin: a novel target for the prevention and retardation of kidney disease? Nature reviews Nephrology. 2013;9(4):223–39. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bardoux P, Bichet DG, Martin H, Gallois Y, Marre M, Arthus MF, Lonergan M, Ruel N, Bouby N, Bankir L. Vasopressin increases urinary albumin excretion in rats and humans: involvement of V2 receptors and the renin-angiotensin system. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2003;18(3):497–506. doi: 10.1093/ndt/18.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meijer E, Bakker SJ, Halbesma N, de Jong PE, Struck J, Gansevoort RT. Copeptin, a surrogate marker of vasopressin, is associated with microalbuminuria in a large population cohort. Kidney Int. 2010;77(1):29–36. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enhorning S, Struck J, Wirfalt E, Hedblad B, Morgenthaler NG, Melander O. Plasma copeptin, a unifying factor behind the metabolic syndrome. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2011;96(7):E1065–72. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roussel R, Fezeu L, Bouby N, Balkau B, Lantieri O, Alhenc-Gelas F, Marre M, Bankir L. Low water intake and risk for new-onset hyperglycemia. Diabetes care. 2011;34(12):2551–4. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho TA, Godefroid N, Gruzon D, Haymann JP, Marechal C, Wang X, Serra A, Pirson Y, Devuyst O. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease is associated with central and nephrogenic defects in osmoregulation. Kidney Int. 2012;82(10):1121–9. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoen T, Blum J, Paccaud F, Burnier M, Bochud M, Conen D. Factors associated with 24-hour urinary volume: the Swiss salt survey. BMC nephrology. 2013;14:246. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Velho G, Bouby N, Hadjadj S, Matallah N, Mohammedi K, Fumeron F, Potier L, Bellili-Munoz N, Taveau C, Alhenc-Gelas F, Bankir L, et al. Plasma copeptin and renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and albuminuria. Diabetes care. 2013;36(11):3639–45. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ong AC, Devuyst O, Knebelmann B, Walz G. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: the changing face of clinical management. Lancet. 2015;385(9981):1993–2002. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60907-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ponte B, Pruijm M, Ackermann D, Vuistiner P, Guessous I, Ehret G, Alwan H, Youhanna S, Paccaud F, Mohaupt M, Pechere-Bertschi A, et al. Copeptin is associated with kidney length, renal function, and prevalence of simple cysts in a population-based study. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2015;26(6):1415–25. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014030260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roussel R, Matallah N, Bouby N, El Boustany R, Potier L, Fumeron F, Mohammedi K, Balkau B, Marre M, Bankir L, Velho G. Plasma Copeptin and Decline in Renal Function in a Cohort from the Community: The Prospective D.E.S.I.R. Study. American journal of nephrology. 2015;42(2):107–14. doi: 10.1159/000439061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pruijm M, Ponte B, Ackermann D, Paccaud F, Guessous I, Ehret G, Pechere-Bertschi A, Vogt B, Mohaupt MG, Martin PY, Youhanna SC, et al. Associations of Urinary Uromodulin with Clinical Characteristics and Markers of Tubular Function in the General Population. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2016;11(1):70–80. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04230415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roussel R, El Boustany R, Bouby N, Potier L, Fumeron F, Mohammedi K, Balkau B, Tichet J, Bankir L, Marre M, Velho G. Plasma copeptin, AVP gene variants, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in a cohort from the community. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2016 doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-1113. jc20161113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouby N, Bachmann S, Bichet D, Bankir L. Effect of water intake on the progression of chronic renal failure in the 5/6 nephrectomized rat. The American journal of physiology. 1990;258(4 Pt 2):F973–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.4.F973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahrabi AK, Terryn S, Valenti G, Caron N, Serradeil-Le Gal C, Raufaste D, Nielsen S, Horie S, Verbavatz JM, Devuyst O. PKD1 haploinsufficiency causes a syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis in mice. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2007;18(6):1740–53. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perico N, Zoja C, Corna D, Rottoli D, Gaspari F, Haskell L, Remuzzi G. V1/V2 Vasopressin receptor antagonism potentiates the renoprotection of renin-angiotensin system inhibition in rats with renal mass reduction. Kidney Int. 2009;76(9):960–7. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koshimizu TA, Nakamura K, Egashira N, Hiroyama M, Nonoguchi H, Tanoue A. Vasopressin V1a and V1b receptors: from molecules to physiological systems. Physiological reviews. 2012;92(4):1813–64. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taveau C, Chollet C, Waeckel L, Desposito D, Bichet DG, Arthus MF, Magnan C, Philippe E, Paradis V, Foufelle F, Hainault I, et al. Vasopressin and hydration play a major role in the development of glucose intolerance and hepatic steatosis in obese rats. Diabetologia. 2015;58(5):1081–90. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3496-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, Gansevoort RT, Grantham JJ, Higashihara E, Perrone RD, Krasa HB, Ouyang J, Czerwiec FS. Tolvaptan in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367(25):2407–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark WF, Sontrop JM, Macnab JJ, Suri RS, Moist L, Salvadori M, Garg AX. Urine volume and change in estimated GFR in a community-based cohort study. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2011;6(11):2634–41. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01990211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strippoli GF, Craig JC, Rochtchina E, Flood VM, Wang JJ, Mitchell P. Fluid and nutrient intake and risk of chronic kidney disease. Nephrology (Carlton) 2011;16(3):326–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2010.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bankir L, Perucca J, Weinberger MH. Ethnic differences in urine concentration: possible relationship to blood pressure. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2007;2(2):304–12. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03401006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perucca J, Bouby N, Valeix P, Bankir L. Sex difference in urine concentration across differing ages, sodium intake, and level of kidney disease. American journal of physiology Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2007;292(2):R700–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00500.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zittema D, van den Berg E, Meijer E, Boertien WE, Muller Kobold AC, Franssen CF, de Jong PE, Bakker SJ, Navis G, Gansevoort RT. Kidney function and plasma copeptin levels in healthy kidney donors and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease patients. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2014;9(9):1553–62. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08690813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith BH, Campbell H, Blackwood D, Connell J, Connor M, Deary IJ, Dominiczak AF, Fitzpatrick B, Ford I, Jackson C, Haddow G, et al. Generation Scotland: the Scottish Family Health Study; a new resource for researching genes and heritability. BMC medical genetics. 2006;7:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-7-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olden M, Corre T, Hayward C, Toniolo D, Ulivi S, Gasparini P, Pistis G, Hwang SJ, Bergmann S, Campbell H, Cocca M, et al. Common variants in UMOD associate with urinary uromodulin levels: a meta-analysis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2014;25(8):1869–82. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013070781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polasek O, Marusic A, Rotim K, Hayward C, Vitart V, Huffman J, Campbell S, Jankovic S, Boban M, Biloglav Z, Kolcic I, et al. Genome-wide association study of anthropometric traits in Korcula Island, Croatia. Croatian medical journal. 2009;50(1):7–16. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2009.50.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pruijm M, Ponte B, Ackermann D, Vuistiner P, Paccaud F, Guessous I, Ehret G, Eisenberger U, Mohaupt M, Burnier M, Martin PY, et al. Heritability, determinants and reference values of renal length: a family-based population study. European radiology. 2013;23(10):2899–905. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-2900-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ponte B, Pruijm M, Ackermann D, Vuistiner P, Eisenberger U, Guessous I, Rousson V, Mohaupt MG, Alwan H, Ehret G, Pechere-Bertschi A, et al. Reference values and factors associated with renal resistive index in a family-based population study. Hypertension. 2014;63(1):136–42. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jungers P, Hannedouche T, Itakura Y, Albouze G, Descamps-Latscha B, Man NK. Progression rate to end-stage renal failure in non-diabetic kidney diseases: a multivariate analysis of determinant factors. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 1995;10(8):1353–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van den Brand JA, van Boekel GA, Willems HL, Kiemeney LA, den Heijer M, Wetzels JF. Introduction of the CKD-EPI equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate in a Caucasian population. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2011;26(10):3176–81. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sweeney TE, Beuchat CA. Limitations of methods of osmometry: measuring the osmolality of biological fluids. The American journal of physiology. 1993;264(3 Pt 2):R469–80. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.3.R469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vallon V, Komers R. Pathophysiology of the diabetic kidney. Comprehensive Physiology. 2011;1(3):1175–232. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perrier E, Demazieres A, Girard N, Pross N, Osbild D, Metzger D, Guelinckx I, Klein A. Circadian variation and responsiveness of hydration biomarkers to changes in daily water intake. European journal of applied physiology. 2013;113(8):2143–51. doi: 10.1007/s00421-013-2649-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perrier ET, Buendia-Jimenez I, Vecchio M, Armstrong LE, Tack I, Klein A. Twenty-four-hour urine osmolality as a physiological index of adequate water intake. Disease markers. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/231063. 231063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bouby N, Ahloulay M, Nsegbe E, Dechaux M, Schmitt F, Bankir L. Vasopressin increases glomerular filtration rate in conscious rats through its antidiuretic action. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 1996;7(6):842–51. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V76842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bottin JH, Lemetais G, Poupin M, Jimenez L, Perrier ET. Equivalence of afternoon spot and 24-h urinary hydration biomarkers in free-living healthy adults. European journal of clinical nutrition. 2016 doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2015.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Souza AC, Zatz R, de Oliveira RB, Santinho MA, Ribalta M, Romao JE, Jr, Elias RM. Is urinary density an adequate predictor of urinary osmolality? BMC nephrology. 2015;16:46. doi: 10.1186/s12882-015-0038-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leech S, Penney MD. Correlation of specific gravity and osmolality of urine in neonates and adults. Archives of disease in childhood. 1987;62(7):671–3. doi: 10.1136/adc.62.7.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berl T. Impact of solute intake on urine flow and water excretion. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2008;19(6):1076–8. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007091042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zerbe RL, Miller JZ, Robertson GL. The reproducibility and heritability of individual differences in osmoregulatory function in normal human subjects. The Journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 1991;117(1):51–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Share L, Crofton JT, Ouchi Y. Vasopressin: sexual dimorphism in secretion, cardiovascular actions and hypertension. The American journal of the medical sciences. 1988;295(4):314–9. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198804000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perinpam M, Ware EB, Smith JA, Turner ST, Kardia SL, Lieske JC. Key influence of sex on urine volume and osmolality. Biology of sex differences. 2016;7:12. doi: 10.1186/s13293-016-0063-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cowley AW, Jr, Skelton MM, Velasquez MT. Sex differences in the endocrine predictors of essential hypertension. Vasopressin versus renin. Hypertension. 1985;7(3 Pt 2):I151–60. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.7.3_pt_2.i151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chun TY, Bankir L, Eckert GJ, Bichet DG, Saha C, Zaidi SA, Wagner MA, Pratt JH. Ethnic differences in renal responses to furosemide. Hypertension. 2008;52(2):241–8. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.109801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Katz AI, Massry S, Agmon J, Toor M. Concentration and dilution of urine in permanent inhabitants of hot regions. Israel journal of medical sciences. 1965;1(5):968–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson RH, Corbett JL, Wilkinson RH. Desert journeys by Bedouin: sweating and concentration of urine during travel by camel and on foot. Nature. 1968;219(5157):953–4. doi: 10.1038/219953a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berlyne GM, Yagil R, Goodwin S, Morag M. Drinking habits and urine concentration of man in southern Israel. Israel journal of medical sciences. 1976;12(8):765–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taylor GO, Oyediran AB, Saliu I. Effects of haemoglobin electrophoretic pattern and seasonal changes on urine concentration in young adult Nigerian males. African journal of medicine and medical sciences. 1978;7(4):201–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kristal-Boneh E, Glusman JG, Chaemovitz C, Cassuto Y. Improved thermoregulation caused by forced water intake in human desert dwellers. European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology. 1988;57(2):220–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00640666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bankir L, Bochud M, Maillard M, Bovet P, Gabriel A, Burnier M. Nighttime blood pressure and nocturnal dipping are associated with daytime urinary sodium excretion in African subjects. Hypertension. 2008;51(4):891–8. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.105510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kimura G, Dohi Y, Fukuda M. Salt sensitivity and circadian rhythm of blood pressure: the keys to connect CKD with cardiovascular events. Hypertension research : official journal of the Japanese Society of Hypertension. 2010;33(6):515–20. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guerrot D, Hansel B, Perucca J, Roussel R, Bouby N, Girerd X, Bankir L. Reduced insulin secretion and nocturnal dipping of blood pressure are associated with a disturbed circadian pattern of urine excretion in metabolic syndrome. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2011;96(6):E929–33. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burnier M, Coltamai L, Maillard M, Bochud M. Renal sodium handling and nighttime blood pressure. Seminars in nephrology. 2007;27(5):565–71. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fezeu L, Bankir L, Hansel B, Guerrot D. Differential circadian pattern of water and Na excretion rates in the metabolic syndrome. Chronobiology international. 2014;31(7):861–7. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2014.917090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.