Abstract

Accurate and timely expression of specific genes guarantees the healthy development and function of the brain. Indeed, variations in the correct amount or timing of gene expression lead to improper development and/or pathological conditions. Almost forty years after the first successful gene transfection in in vitro cell cultures, it is currently possible to regulate gene expression in an area-specific manner at any step of central nervous system development and in adulthood in experimental animals in vivo, even overcoming the very poor accessibility of the brain. Here, we will review the diverse approaches for acute gene transfer in vivo, highlighting their advantages and disadvantages with respect to the efficiency and specificity of transfection as well as to brain accessibility. In particular, we will present well-established chemical, physical and virus-based approaches suitable for different animal models, pointing out their current and future possible applications in basic and translational research as well as in gene therapy.

Keywords: In vivo genetic manipulations, Nanoparticles, Polymers, Electroporation, Sonoporation, Viruses

1. Introduction

Proper development of the central nervous system (CNS) determines its function and consequent behaviors. Accordingly, numerous gene alterations during development lead to brain disorders characterized by a variety of abnormal behaviors, often depending on which brain area is mostly affected. On the other hand, gene alterations during adulthood may also lead to a variety of brain-related diseases and neurodegenerative disorders that vary in their symptoms, depending on the affected brain areas. This complexity highlights the need for temporal and spatial regulation of specific genes for proper brain function. Accordingly, the development of reliable techniques for gene transfection in vivo has recently attracted the attention of an increasing number of researchers as a means to study and understand the roles of the diverse genes underlying the basic mechanisms of CNS development and function (basic research) and to study genes involved in CNS disorders to find new possible treatments (translational research). In particular, in recent years, basic research has benefited from new tools for gene editing (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9 technology; Ahmad et al., 2018) and neuronal-activity modulation (optogenetics and chemogenetics; Dobrzanski and Kossut, 2017; Towne and Thompson, 2016), which both need to be coupled to a nucleic acid delivery system. For translational research, a fast-growing field of study focuses on the possibility of treating CNS disorders by manipulating gene expression (gene therapy) rather than by classical pharmacology, which has proven highly ineffective in the last 10 years (Gribkoff and Kaczmarek, 2017). Thus, regardless of the final application, the development of novel methods for modulating gene expression in vivo has acquired increasing importance in recent years. This modulation can be achieved either by the generation of genetically modified animals or by acute procedures for gene expression modulation. Here, we will only review the latter.

Generally, an acute modulation of gene expression requires a transfection or transduction process (i.e., a procedure that introduces foreign nucleic acids, such as DNA/RNA, into a cell) to produce genetically modified cells or organisms by nonviral or viral methods, respectively. Indeed, many molecules, such as nucleic acids and certain drugs, are not able to diffuse through the lipophilic cell membrane due to their physicochemical properties (e.g., hydrophilicity, charge) and/or size. Thus, the support of specific carriers or chemical/physical stimulation is often necessary to increase the efficiency of the transfection process.

Although highly efficient, acute introduction of DNA into mammalian cells in vitro was achieved a long time ago (Graham and van der Eb, 1973), for the last four decades, scientists have struggled to increase the efficiency of this process in vivo (Crystal, 2014). For example, circulating nucleic acids for transfection have a very short half-life in vivo because they are degraded by circulating nucleases in the blood. Moreover, targeting specific organs and cell types at discrete times is generally challenging in vivo and is particularly difficult in the case of the brain for a number of reasons. First, the brain is an isolated, inaccessible environment due to the presence of the skull and the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which separates circulating blood from the brain’s extracellular fluid. Second, the brain contains several different areas that are each characterized by specific functions, rendering area-specific transfection crucial in this organ. Third, the CNS contains hundreds of billions of neuronal and glial cells characterized by high diversity (e.g., even among neurons, there is a wide variety of diverse types with diverse functions). Finally, neurons are postmitotic cells that do not divide, requiring a cell cycle-independent introduction of genetic material.

Since almost ninety-five percent of the animals used in research are mice and rats (Badyal and Desai, 2014), we will focus this review on rodents. For a long time, the dominant approach for acute gene transfer in vivo in rodents was the design of different viral vectors with increasingly higher efficiency of transfection and tissue specificity (see viral methods below). Nevertheless, due to limitations related to the safety of viral gene transfer, many physical strategies have also been adopted, such as electroporation and sonoporation (see physical methods below). However, physical methods require strong conditions (e.g., strong electric field or ultrasound) for efficient transfection, and thus a range of synthetic carriers for nucleic acids suited for chemical transfection have also been created (see chemical methods below; Yin et al., 2014). In recent years, different methods have also been combined (e.g., physical and chemical methods or viruses and physical methods) to try to overcome the shortcomings of one method vs the other while taking advantage of the positive features of both.

In this review, we describe the currently available methods for the delivery of nucleic acids to the CNS in vivo. First, we focus on chemical methods, which include a wide selection of nucleic acid carriers that allow crossing of the cell membrane. Second, we describe physical methods, which take advantage of physical forces to increase membrane permeability and possibly direct nucleic acids to the desired location. Third, we address viral-based techniques, which explore the intrinsic transfection ability of viruses. Interestingly, all of the described techniques are very different, but they each present some level of overlap, creating a great portfolio to choose from when designing diverse experiments with gene transfer in vivo. Here, we will note the advantages and disadvantages of each described method and will indicate their best-suited applications.

2. Chemical methods for transfection

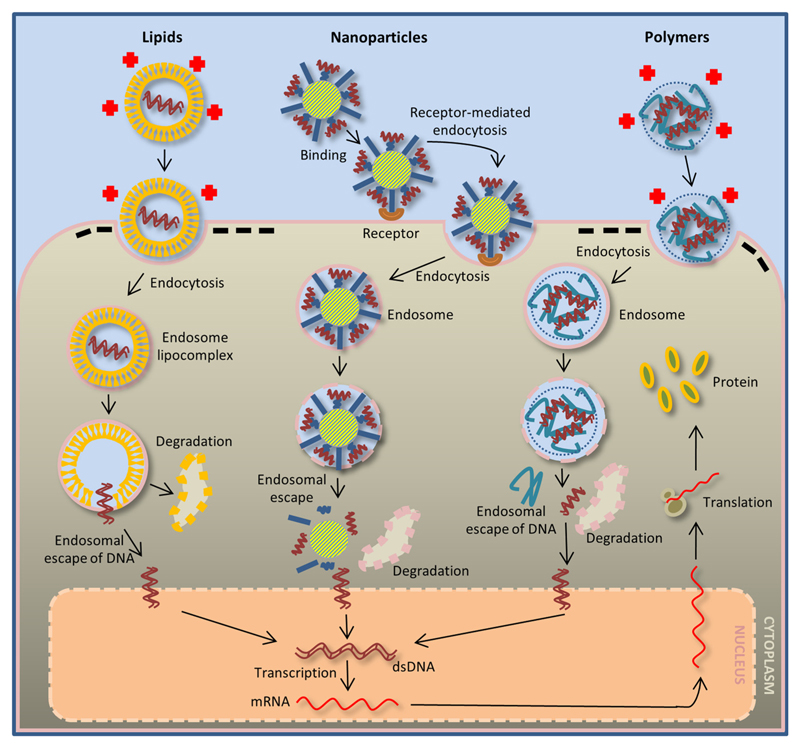

Chemical methods of transfection are a set of techniques that rely on external carriers characterized by specific chemical properties that are essential for transfection of the exogenous nucleic acids of interest (Table 1). In particular, chemical carriers are prepared to favor the formation of complexes with the nucleic acids and internalization by endocytosis in the target cells. There, the genetic material is released into the cytoplasm through endosomal escape and subsequently enters the nucleus for transcription into messenger RNA (mRNA), followed by translation into functional proteins in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1). Chemical methods often have good gene-packaging capacity and low immunogenicity and toxicity, and they are relatively safe for the operator (Zhi et al., 2018). Nevertheless, most chemical methods have low efficiency, and they still rely on invasive methods of administration for in vivo applications (e.g., intrathecal/intraventricular injections). Only recently, the rapid development of materials science and nanoscience has allowed the construction of more efficient chemical vectors for in vivo transfection; these vectors are useful for not only basic research but also the biomedical field (Glover et al., 2005; Lu and Jiang, 2017; Ramamoorth and Narvekar, 2015; Yin et al., 2014). Here, we will focus on three main groups of chemicals that are often used as vectors.

Table 1.

Chemical methods for transfection.

| Group | Type/Helper | Toxicity | In vivo delivery method | Efficiency/Stability | BBB accessibility | Most Prominent Applications (references) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipids | Liposomes | → | N/A | ↓ | N/A | Nayerossadat et al., 2012 |

| Cationic lipid mix/PEG | ↓ | Intraventricular injection | → | N/A | Hassani et al., 2005; Nayerossadat et al., 2012; Yin et al., 2014;Zhi et al., 2018 | |

| Cationic lipid mix/DOPE | ↓ | Intraventricular injection, Intratumoral (glioblastoma) injection | ↑ | N/A | Roessler and Davidson et al., 1994; Hassani et al., 2005; Pulkkanen and Yla-Herttuala, 2005; Lagarce and Passirani, 2016;Cikankowitz et al., 2017 | |

| Lipid Nanoemulsions | ↓ | Intranasal | ↑ | N/A | Ramamoorth and Narvekar, 2015; Yadav et al., 2016 | |

| Solid lipid nanoparticles | ↓ | Intravenous injection | ↑ | Possibly | Jin et al., 2011; Pathak et al., 2017 | |

| Nanoparticles | Silica | ↓ | Subventricular injection, Intracortical injection | ↑ | N/A | Bharali et al., 2005; Luo and Saltzman, 2006 |

| Gold nanoparticles | ↓ | Systemic injection | → | + | Jensen et al., 2013; Escudero-Francos et al., 2017; Takeuchi et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2018 | |

| Carbon Nanotubes | ↓ | Intraventricular injection | ↑ | N/A | Al-Jamal et al., 2011; Costa et al., 2016 | |

| Polymers | Polyethylenimine | ↑ | Intracortical injection | ↓ | (+ with PEG) | Abdallah et al., 1996; Lungwitz et al., 2005; Nouri et al., 2017 |

| Polyethylenimine/RVG | ↑ | Tail injection | ↓ | + | Hwang et al., 2011 | |

| Chitosans/PEG | ↓ | Intratumoral (glioblastoma) injection | ↑ | – | Duceppe and Tabrizian, 2010; Danhier et al., 2015; Ramamoorth and Narvekar, 2015 | |

| ChitosansTrimethylated/PEG + RVG | ↓ | Intravenous injection | ↑ | + | Gao et al., 2014 | |

| Polyamidoamine (with various functionalizations) | ↓ | Tail injection, Systemic injection, Intravenous administration | ↑ | + | Huang et al., 2007;Huang et al., 2008;Ke et al., 2009;Zarebkohan et al., 2015 |

↓high / →medium / ↓low / +yes / -no / N/A-information not available.

Fig. 1. Chemical methods of gene delivery.

Lipid-mediated gene transfer (left) occurs by the interaction between the positively charged surface of the carriers and the negatively charged cell membrane. This interaction promotes endocytosis, creating an endosome lipocomplex. The complex is then degraded in the cell cytoplasm, and the released DNA is transported to the nucleus. Nanoparticle-mediated gene transfer (middle) occurs by the nanoparticles binding to receptors on the cell surface, followed by endocytosis. During endosome degradation in the cell cytoplasm, the DNA attached to the core of the nanoparticles is released and transported to the nucleus. Similar to lipid-mediated gene transfer, polymer-mediated gene transfer (right) occurs via charge differences between the carriers and the cell membrane, which promotes binding and endocytosis. During endosome degradation, the DNA is released from the polymer structure and is transported to the nucleus. After DNA transcription, the mRNA exits the nucleus, and it is translated into a protein in the cytoplasm.

2.1. Lipids

The use of lipid carriers for transfection (i.e., lipofection) for in vitro cell delivery has been widespread since the 1980s (Fraley et al., 1980; Lu et al., 1989). Cationic lipids – the most commonly used lipids – are synthetic lipids with a positively charged hydrophilic domain connected by a linker to a long lipophilic tail. During transfection, the negatively charged phosphate on the backbone of the nucleic acids interacts with the hydrophilic domain on the lipid, creating a structure called lipoplex (2–200 nm in diameter; (Higuchi et al., 2006; Inoh et al., 2017; Ramamoorth and Narvekar, 2015; Ross and Hui et al., 1999)). Once the lipoplex reaches the cell membrane, it is internalized by endocytosis, and the genetic material is then released from the endosomes inside the cell (Nayerossadat et al., 2012; Fig. 1). Although the highly positive charge on the surface of the lipids protects the genetic material from cleavage by circulating endonucleases (Ramamoorth and Narvekar, 2015), lipid-based vectors still suffer from a short half-life in vivo because. This is due to the rapid degradation of lipid particles by the reticuloendothelial system, which is composed of phagocytic cells located in connective tissues (Nayerossadat et al., 2012; Petschauer et al., 2015; Song et al., 2014). To overcome this issue, the DNA and cationic lipid mixture is often supplemented with so-called helper lipids (the most common being polyethylene glycol (PEG) and 1,2-dioleoyl-phosphatidyl-ethanolamine (DOPE)). These are neutral lipids that increase the lipoplex’s stability, thus increasing its serum half-life. Moreover, the addition of helper lipids also increases the fusion between the lipid particle and the cell membrane and facilitates the movement of genetic material between the endosomes and the cell nucleus (Hassani et al., 2005; Nayerossadat et al., 2012; Yin et al., 2014; Zhi et al., 2018). Finally, depending on the composition of the cationic lipid mixture and the concentration of the genetic material, lipoplexes may assume different tertiary structures that may favor transfection efficiency. This structural variation is mainly due to different charge distributions on their surface and different areas of interaction with the cell. For example, the hexagonal phases of a lipoplex can spontaneously release the DNA content when these lipoplexes are in contact with an anionic vesicle, whereas a multilamellar vesicular structure (where the genetic material is sandwiched between lipid multilayers) tends not to release its contents. Interestingly, the transition from multilamellar to hexagonal structures is favored by the addition of DOPE to the lipid-DNA mixtures (Dan, 2015; Ma et al., 2007). Due to all these practices that increase transfection efficiency, lipids have proven to be efficient in vivo for gene transfection by direct injection in the ventricle or brain of mice (Hassani et al., 2005; Roessler and Davidson et al., 1994). Moreover, lipids have been used as a gene-delivery method for the treatment of glioblastomas by intratumoral injection (Cikankowitz et al., 2017; Lagarce and Passirani, 2016; Pulkkanen and Yla-Herttuala, 2005).

Another structural arrangement that may occur among cationic lipids is a nanoemulsion. A lipid nanoemulsion (LNE) is a dispersion of nanoparticles of lipids (100–400 nm in diameter) in a liquid phase that is obtained in vitro by the addition of a surfactant agent to prevent the lipids from coalescing into a macroscopic phase. The main advantages of LNEs include easy processing, low costs and easy scale up to large-scale production (Liu and Yu et al., 2010; Ramamoorth and Narvekar, 2015). LNEs have been successfully used in vitro, showing a higher efficiency than liposomes (Liu and Yu et al., 2010). The usage of nanoemulsions in vivo is becoming more popular due to their low toxicity and high stability (Ramamoorth and Narvekar, 2015). For example, successful delivery of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) small interfering RNA (siRNA) to treat lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced neuroinflammation has been achieved in rats (Kim et al., 2010). Of note, the small dimension of the nanoparticles has also allowed intranasal delivery, a convenient way of overcoming the impermeability of the BBB and preventing the action of blood-circulating nucleases that may digest the DNA of interest (Yadav et al., 2016).

Lastly, lipid carriers have also been recently used in the form of solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs). SLNs are lipid nanospheres (70–230 nm in diameter) with an outer hydrophilic shell made of a phospholipid double layer and an inner core containing long-chained lipids, generating particles that are solid and stable at body temperature (Kaur et al., 2008). In the last decade, there has been increased interest in the use of these nanoparticles for gene delivery, mainly due to their stability and biocompatibility (Pathak et al., 2017). Interestingly, SLNs were used to deliver siRNAs against c-met in a murine model of glioblastoma via intravenous injection in vivo, and the treatment showed positive outcomes (Jin et al., 2011). This result highlights the fact that SLNs are very stable and may cross the BBB, making them a very desirable vector for in vivo gene transfection in the brain.

2.2. Nanoparticles

With the rapid development of nanotechnology in the last decade, the use of nanoparticles as a gene-delivery tool has quickly grown. The main advantage of this kind of carrier is its high stability, great protection against circulating nucleases and low risk of toxicity (Bharali et al., 2005). Here, we will focus on the most studied nanoparticles.

2.2.1. Silica and gold nanoparticles

Silica (an oxide of silicon) is a very malleable material that finds applications in all realms of science and engineering. Silica nanoparticles are spheres (30 nm in diameter) that can be relatively easily made and modified during synthesis. In particular, silica nanoparticles coated with organic amino acids can interact with nucleic acids and can protect the genetic material from endonucleases. In vitro studies have shown that upon phagocytosis, coated silica nanoparticles can then be internalized, subsequently releasing DNA (Kneuer et al., 2000a, b). Interestingly, silica nanoparticles have also been used to study the development of newly born neurons in vivo by transfecting an EFGFR1-coding plasmid in the subventricular zone of adult mice with no signs of cell degeneration or systemic or brain-specific toxicity (Bharali et al., 2005; Luo and Saltzman, 2006). However, a recent report showed signs of neuroinflammation in rats following intranasal administration of silica nanoparticles (Parveen et al., 2017). Further studies on the effect of these vectors in the brain are necessary.

Gold nanoparticles are also used as vectors for gene delivery, as gold has been extensively studied in a biological context due to its very low toxicity and its capability to bind a wide array of organic molecules. In particular, some in vitro studies have shown that gold nanoparticles coated with organic cationic molecules are able to bind nucleic acids and are endocytosed, providing efficient delivery of the genetic material (Bishop et al., 2015; Connor et al., 2005; Ekin et al., 2014; Jensen et al., 2013; Levy et al., 2010; Peng et al., 2016). In addition, gold nanoparticles also display strong and tunable optical properties that have been tested in vitro (Pissuwan et al., 2011; Wijaya and Hamad-Schifferli, 2008). Interestingly, gold nanoparticles can possibly cross the BBB, as tested in not only an in vitro model of the BBB (Bonoiu et al., 2009) but also in vivo (Jensen et al., 2013). In particular, successful transfection of a siRNA against the antiapoptotic gene Bcl2 L12 was achieved in glioma cells upon systemic injection of gold nanoparticles in mice. Notably, the siRNA showed little enzymatic degradation (Jensen et al., 2013). Recently, gold nanoparticles functionalized with PEG or other long organic molecules showed much higher BBB permeability (Escudero-Francos et al., 2017; Takeuchi et al., 2018). Remarkably, gold nanoparticles were also used to downregulate α-synuclein in a murine model of Parkinson’s disease following intraperitoneal injection and had positive outcomes on anatomical landmarks of Parkinson’s (Hu et al., 2018).

2.2.2. Fullerenes

Fullerenes are carbon molecules of various shapes and dimensions: spherical fullerenes (SFs) are called Buckminster fullerenes, whereas cylindrical fullerenes with a hollow core are called carbon nanotubes (CNTs). The incredible properties of fullerenes, such as high thermal and electrical conductivity, great strength, and rigidity, put these molecules at the forefront of the fast-developing nanoengineering industry (Yang et al., 2006). Moreover, SFs can be functionalized with cationic charges and thus can stably condense double-stranded DNA into globules (< 100 nm in diameter), which are protective against intracellular and circulating nucleases. Nevertheless, the only known in vivo application to date of SFs is the successful delivery of the Insulin 2 gene directly to the liver in mice with no signs of systemic toxicity (Maeda-Mamiya et al., 2010). Finally, it has been reported that SFs are able to cross the BBB, although there are no reports of their use to deliver genes to the CNS (Quick et al., 2008).

Additionally, CNTs have been studied as a possible vector for gene delivery. Nevertheless, applying their use to the biomedical realm has proven difficult because CNTs are poorly soluble in water. One strategy to increase their water solubility is functionalization of their surface. Indeed, CNTs functionalized with peptides and conjugated to DNA or RNA are able to successfully penetrate the cell membrane, and the DNA-functionalized CNTs are able translocate to the nucleus in in vitro systems (Lacerda et al., 2008; Pantarotto et al., 2004; Singh et al., 2005). Nevertheless, the in vivo application of CNTs is still in its early stages (Lacerda et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2014). Notably, Khuloud et al. transfected the brain cortex in a rat model of ischemia with CNTs functionalized with siRNA for Caspase 3. This treatment successfully decreased the apoptotic cells around the lesion, with amelioration of motor deficits in the operated rats (Al-Jamal et al., 2011; Costa et al., 2016). Thus, although the application of fullerenes in biology is still in its infancy, it is clear that these carbon nanomolecules offer a new, interesting perspective on the upcoming development of gene-delivery vectors (Montellano et al., 2011)

2.3. Polymers

Polymers are macromolecules composed of repeated units. Similar to lipoplexes, the polymers used for gene delivery have a positively charged surface that interacts with the negatively charged backbone of nucleic acids to form complexes called polyplexes. Among the polymer materials used for transfection, polyethylenimine (PEI) is one of the most effective vectors in vitro and in vivo (Pack et al., 2005). PEI is a synthetic, water-soluble polymer (0.8 −1000 kDa in molecular weight), and its structural complexity can vary from linear to highly branched (Ewe et al., 2016; Ramamoorth and Narvekar, 2015). PEIs are internalized through phagocytosis by cells and can avoid endosome digestion/degradation via a proton-sponge effect. Due to their highly positive charge (derived from the large number of partially protonated amino groups that they possess), PEIs can stop the natural acidification of the endosome, generating strong osmotic imbalances, ultimately causing endosome rupture and release of the polymer and the conjugated genetic material into the cytoplasm. Moreover, the highly positive charge acts as a protective factor against the action of cytoplasmatic nucleases (Ewe et al., 2016). Interestingly, many studies showed promising prospects for the use of PEI in vivo. For example, in a classic study, PEI-based vectors were used to successfully and safely deliver luciferase DNA to the brain through intracortical and intrahippocampal injections with no animal morbidity (Abdallah et al., 1996). Since then, PEI-based vectors have been used to deliver genetic material to different CNS regions, such as the spinal cord (Shi et al., 2003; Shimamura et al., 2004), the cortex in a murine model of ischemia (Oh et al., 2017) and stem cells located in the subventricular zone (Lemkine et al., 2002). The delivery occurred by direct brain injection since PEI-based vectors were believed not to cross the BBB (Lungwitz et al., 2005). Recently, a PEI-based vector was used to successfully downregulate α-synuclein using a specific siRNA in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease after one single intraventricular injection (Helmschrodt et al., 2017).

To overcome the potential low BBB permeability, PEI was linked to a peptide from the rabies virus (RVG), and this method was used to successfully deliver microRNA to the brain in vivo following tail injection (Hwang et al., 2011). Moreover, PEI functionalized with PEG was used to deliver a plasmid coding the gene CD200 in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis (CD200 shows decreased expression in this condition). Notably, the PEI-based carrier functionalized with PEG was able to cross the BBB (Nouri et al., 2017). Remarkably, the transfection of hypoglossal motor neurons was achieved by retrograde axonal transport, which followed the injection of PEI complexed with DNA into the tongue of an experimental rat (Wang et al., 2001).

Despite the abovementioned successes, further use of PEI for in vivo transfection has been hindered by the relatively high toxicity of this polymer and its low rate of uptake by living cells, leading to low transfection efficiency. Thus, in the past few years, attention has turned to less toxic polymers, such as chitosans. Chitosans are natural polymers made of randomly distributed β-(1-4)-linked D-glucosamine and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine and are considered very attractive vectors for gene delivery in vivo. Indeed, chitosans are nontoxic at all concentrations and can be efficiently functionalized (Duceppe and Tabrizian, 2010; Ramamoorth and Narvekar, 2015). For example, PEGylated chitosan polymers were used to deliver siRNA against Galectine-1 and EGFR, two genes known to increase the resistance of glioblastoma cells to treatment with temozolomide. The delivery, which was performed by intratumoral injection, resulted in an increased survival rate of the animals (Danhier et al., 2015). Although chitosan-based polymers cannot readily cross the BBB, this issue was overcome by extensively modifying the chitosan structure. In particular, chitosans were first trimethylated, generating a trimethylated chitosan (TMC), which increased the solubility and siRNA binding to the polymer. Subsequently, PEG was conjugated to TMC. Similar to the reports for lipid-based delivery methods, the addition of PEG increased the biocompatibility and serum stability of the construct. Notably, upon intravenous administration, the specific delivery of Cy5.5-siRNA (a fluorescent probe used to visualize RNA) to the brain in vivo was obtained by adding a fragment derived from a rabies virus glycoprotein to PEG-modified TMC (Gao et al., 2014). Remarkably, chitosan-based vectors were used to transfect HIV-infected astrocytes with siRNA against genes necessary for viral replication, successfully halting the HIV infection. In this study, the chitosan nanoparticles were conjugated to antibodies that could bind to the transferrin receptor in the BBB strongly, increasing the permeability of the brain to the vectors (Gu et al., 2017).

Another class of polymers is dendrimers, highly branched synthetic polymers that have been growing in popularity in biomedical research. This interest is mainly due to their well-defined structure and high density of easily modifiable functional groups (Hu et al., 2016). Topologically, dendrimers are composed of a core, and the branching is organized around this core, forming a spherical structure that is usually positively charged with modifiable functional groups on the surface. Due to their high density of positive charges, dendrimers escape the endosome through the “proton sponge mechanism”, similar to PEI-based polymers (Hu et al., 2016). Among the large array of dendrimers, the most commonly used and the best-characterized one is polyamidoamine (PAMAM; (Hu et al., 2016; Pack et al., 2005)). PAMAM has been extensively used in vitro due to its low cytotoxicity (Eichman et al., 2000). To increase gene transfer efficiency and biocompatibility, many functionalizations of PAMAM have been performed; these functionalizations include the substitution of positive charges with arginine groups (Choi et al., 2004), PEG (Luo and Saltzman, 2006; Wang et al., 2009), and pyridine/histidine (Hashemi et al., 2016) and the addition of hydrophobic chains, including lauroyl (Santos et al., 2010). Nevertheless, as a positively charged hydrophilic molecule, PAMAM cannot cross the BBB in vivo. To circumvent this problem, PAMAM was functionalized with PEG and SRL, a small, artificially generated peptide, and was able to cross the BBB. After internalization by phagocytosis and interaction with the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) on the BBB, PAMAMs functionalized with SRL were able to efficiently transfect neurons in vivo with a plasmid DNA coding EGFP following their intravenous injection in the tail of mice (Zarebkohan et al., 2015). Similarly, different peptides that present high brain penetration, such as angiopep-2 (Ke et al., 2009), lactoferrin (Huang et al., 2008) and transferrin (Huang et al., 2007), were used to transfect brain cells in vivo. Thus, due to its possible functionalizations and increased BBB permeation, PAMAM potentially has great promise in applications as a gene-delivery vector in vivo.

3. Physical methods for transfection

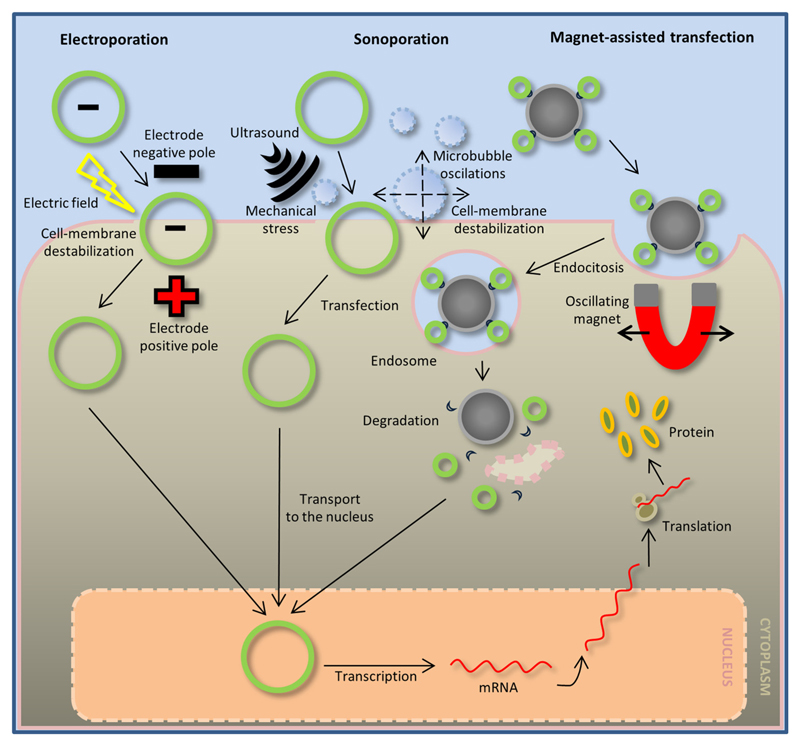

Physical methods are a collection of nonviral techniques for cell transfection that rely on physical stimulation to deliver and direct genetic material inside the living cell (Table 2). Physical methods promote reversible alterations in the cell plasma membrane or endocytosis to allow the direct passage of the molecules of interest into the cell, either alone or with the support of chemical carriers, as described above (Fig. 2). Physical stimulations can, at least in part, overcome many of the side effects linked to biochemical or viral techniques. In particular, the lack of toxicity, the lack of limitations on the length of the coding sequence, and the low costs are among the main advantages. Physical methods have outstanding experimental value in basic brain research. On the other hand, their potential translational application in gene therapy is heavily hampered by the invasiveness of their procedures (e.g., the application of strong electric fields and intraventricular injections) and their low efficiency when DNA delivery is performed systemically (e.g., reduced brain accessibility through the BBB).

Table 2.

Physical methods for transfection.

| Group | Type/Helper | Toxicity | In vivo delivery method | Efficiency/Stability | BBB accessibility | Most Prominent Applications (references) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electroporation | In utero | ↓ | Intraventricular injection | ↑ | N/A | Saito, 2006;Dal Maschio et al., 2012;Szczurkowska et al., 2016 |

| Exo utero | ↓ | Intraventricular injection | ↑ | N/A | Akamatsu et al., 1999; Saba et al., 2003 | |

| Postnatal | ↓ | Intraventricular injection, Stereotaxic micro injection | ↑ | N/A | Boutin et al., 2008; Chesler et al., 2008;Kitamura et al., 2008 | |

| Sonoporation | Microbubbles | → | Systemic injection, Intraventricular injection | ↓ | – | Endoh et al., 2002;Tan et al., 2016 |

| Magnet-assisted transfection | Magnetic nanoparticles/PEI | ↓ | Lumbar intrathecal injection, Stereotaxic injection | → | – | Song et al., 2010;Soto-Sanchez et al., 2015 |

↑high / →medium / ↓low / +yes / -no / N/A-information not available.

Fig. 2. Physical methods of gene delivery.

Electroporation-mediated gene transfer (left) enables the directional guidance of plasmids carrying the negatively charged DNA of interest towards the positive pole of the electrode. At the same time, electroporation causes destabilization of the structure of the cell membrane, creating temporary pores in its surface and allowing the plasmid to enter the cell. The plasmid is then transported to the nucleus. Sonoporation-mediated gene transfer (middle) occurs by ultrasound application, which promotes destabilization of the cell membrane in the presence of oscillating microbubbles. During this process, the plasmid contained in the microbubble mixture enters the cell and is then transported to the nucleus. Magnet-assisted transfection (right) is mediated by magnetic field oscillations that guide and promote endocytosis of the magnetic carriers with attached DNA. In the cytoplasm of the cell, the endosome undergoes degradation and the released DNA enters the cell nucleus. After DNA transcription, the mRNA exits the nucleus, and it is translated into a protein in the cytoplasm.

The first successful in vitro gene transfer supported by physical stimulation was performed in 1980 with transfers into mouse glioma cells by electroporation. The same approach was used for the first in vivo transfection in skin cells of mice (Titomirov et al., 1991). Over the years, other physical methods were proposed for in vivo gene transfer, including magnet-assisted transfection (Mah et al., 2002b; Scherer et al., 2002) and ultrasound application (Sheyn et al., 2008).

3.1. Electroporation

The electroporation technique was already used in vitro in the 1980s (Neumann et al., 1982; Potrykus et al., 1985; Potter, 1988) as an acute, quick, easy, highly efficient, low cost and mostly nontoxic procedure to transfect bacteria and most cell types and to create transgenic plants. Electroporation enables the transfection of large, highly charged molecules that cannot passively diffuse across the lipophilic cell membrane by creating temporary water-filled holes in the membrane (20–120 nm in diameter; (Chang and Reese et al., 1990)) through the application of a series of electric-field pulses. Moreover, application of the electric field also directs the charged molecules for transfection towards the anode side, thus driving them in the desired direction towards the area where the cells of interest are located. Conveniently, once the exposure to the electric pulse is completed, the cell membrane reorganizes by closing the temporary hydrophilic pores and returning to its physiological structure, which traps the exogenous material inside the cell. Recently, the electroporation technique has evolved into diverse applications in vivo (in and ex ovo, in and ex utero, as well as postnatal electroporation) with one of the main advantages being the fast onset of expression of the protein encoded by the transfected DNA. In general, all the in vivo electroporation methods for the CNS share the same concept: the DNA solution is injected into the lumen of the CNS ventricular system. Indeed, at the interface between the lumen of the ventricular system and the brain, there is a neuroepithelium where the neuronal progenitors of different brain areas are located. Thus, following exposure to an electric field applied by a multipolar electrode, negatively charged DNA is directed towards the positively charged electrode and incorporated in the specific populations of neuronal progenitor cells. Those progenitors will generate newly born neurons committed to different brain areas, where the neurons will start migrating upon birth, eventually allowing transfection of those discrete brain regions.

3.1.1. In utero, exo utero and postnatal electroporation

In vivo electroporation was applied as a gene transfer method in 1997 in chick embryos in ovo (Muramatsu et al., 1997). Just four years later, the first CNS transfections of mouse and rat embryos were performed using in utero and exo utero electroporation (Fukuchi-Shimogori and Grove et al., 2001; Saito and Nakatsuji, 2001; Tabata and Nakajima, 2001).

The in utero electroporation (IUE) technique is based on the direct injection of exogenous nucleic acids into the ventricular system of embryos through the uterine wall of a pregnant dam. Then, the electric field is applied to the neuronal progenitors by means of two extrauterine forceps-type electrodes placed on the sides on the embryo head. Since the injection of the nucleic acid solution occurs through the uterine walls with no major damage to the uterus, the pregnant dam is able to deliver the pups. This process allows both embryonal and postnatal studies of the electroporated pups. High efficiency with the two standard forceps-type paddle electrodes has been achieved for the electroporation of pyramidal neurons in the rodent somatosensory cortex (Saito, 2006). Since then, IUE has become the gold standard for studies on cortical development ex vivo, both at the anatomical and functional levels (LoTurco et al., 2009; Tabata and Nakajima, 2008; Taniguchi et al., 2012). Over the years, researchers have achieved targeting of many other brain regions by simply changing the orientation of the forceps-type electrodes. Indeed, by tilting the bipolar electrode, it is possible to target the visual cortex (Cang et al., 2005; Mizuno et al., 2007; Saito and Nakatsuji, 2001), hippocampus (Conrad et al., 2010; Saito and Nakatsuji, 2001; Tomita et al., 2011), olfactory bulb (Imamura and Greer et al., 2013), ganglionic eminence (Borrell et al., 2005; Tanaka et al., 2006), thalamus (Haddad-Tovolli et al., 2013), hypothalamus (Haddad-Tovolli et al., 2013), midbrain, amygdala (Remedios et al., 2007; Soma et al., 2009) cerebellum (dal Maschio et al., 2012; Kita et al., 2013; Szczurkowska et al., 2016; Yamada et al., 2014), spinal cord (Saba et al., 2003) and brainstem (David et al., 2014), but with a highly variable degree of efficiency (dal Maschio et al., 2012; Szczurkowska et al., 2016). Recently, the addition of a third electrode to the standard electroporation configuration has enabled highly reliable bilateral transfection of the hippocampus; the prefrontal, motor and visual cortices; and the cerebellum in a single electroporation episode (dal Maschio et al., 2012; Szczurkowska et al., 2016, 2013). Notably, although transfection is confined to a specific brain region and although not all cells in that region are transfected, successful behavioral studies have been performed. For example, animals have been transfected in utero with DISC1 cDNA, leading to amphetamine hypersensitivity (Vomund et al., 2013), and DCX KO mice have been transfected with DCX cDNA, leading to rescued epileptic-seizure susceptibility (Manent et al., 2009). Moreover, IUE has also been used in studies on psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, indicating the molecular pathways that lead to cognitive deficits (Kamiya, 2009; Taniguchi et al., 2012).

One of the possible variations of the IUE technique is exo utero electroporation (EUE). In this case, during surgery, embryos are removed from the uterus. After DNA injection and delivery of the electric field with the forceps-type electrodes, the embryos are placed back inside the abdominal cavity of the dam without stitching the uterine walls. Since EUE guarantees better accessibility to the embryos than IUE, difficult-to-reach structures, such as the rhombencephalon (Akamatsu et al., 1999), spinal cord and caudal hindbrain (Saba et al., 2003), can be transfected with higher precision. Exo utero electroporation is mostly used for studying prenatal stages, as development of the embryos out of the uterus does not allow vaginal delivery. However, for postnatal studies, it is possible to rescue the electroporated embryos right before birth (E18.5) by Cesarean section, followed by immediate fostering with a stranger mother. Nevertheless, this procedure carries the risk of the pup’s rejection by the foster mother.

It is possible to use the same principle of IUE to transfect animal brains after birth, enabling the study of postnatal brain development. In early postnatal electroporation, DNA is delivered to the brain ventricle or to the subventricular zone using a stereotactic microinjector (Boutin et al., 2008; Chesler et al., 2008), and the animal’s head is conveniently placed between the plates of the forceps-type electrodes. This process allows transfection of the progenitors located in the lateral, septal, and dorsal walls of the lateral ventricle, resulting in the transfection of different types of olfactory bulb neurons (Boutin et al., 2008; Chesler et al., 2008; De Vry et al., 2010; Fernandez et al., 2011; Sonego et al., 2013).

Finally, in adult rodents (up to 3,5 months old), DNA can be injected into the ventricle or directly into the targeted brain area to achieve the selective transfection of specific brain regions without affecting neurodevelopment. In the case of adult electroporation, the electric pulses can be applied with the standard forceps electrode (Chesler et al., 2008; Kitamura et al., 2008), or - for more precise and region-specific electroporation - a needle-like electrode can be inserted directly in the targeted brain region after local application of the DNA solution (Tanaka et al., 2000; Zhao et al., 2005). Late postnatal electroporation has been used to target the dentate gyrus (DG; (De Vry et al., 2010)) and the CA1 region (Tanaka et al., 2000) of the hippocampus, the prefrontal cortex (Zhao et al., 2005), the barrel cortex (Kitamura et al., 2008), and the cerebellum (Kitamura et al., 2008).

3.2. Sonoporation

Sonoporation takes advantage of temporary pores created in the cell membrane by ultrasound (US) exposure. The uptake of the DNA carriers during exposure to US occurs by mechanical stress, which causes endocytosis and/or large membrane wounds that are later closed by endogenous vesicle-based repair mechanisms (Fig. 2; Escoffre et al., 2013). US pulses can be delivered on their own, but their delivery in combination with a local application of microbubbles increases the efficiency of transfection (Taniyama and Morishita, 2006). Indeed, microbubbles are gas-filled structures (1–8 μm in diameter) that can react to the ultrasound waves by sequential expansion and compression (Lentacker et al., 2014), causing their own local oscillation close to the cell membrane and increasing the permeability to exogenous material (e.g., DNA). Moreover, the physicochemical composition of the microbubbles can increase their chances of binding or capturing DNA. In particular, the most commonly used microbubbles are proteins, lipids or polymers (see chemical methods above). So far, the most suitable solution for microbubbles comprises cationic lipids, which can easily bind negatively charged plasmid DNA and are easily disrupted by US.

Although sonoporation is a promising technique that is well established for in vitro gene transfer (Fischer et al., 2006), its in vivo application is hindered by the possible aversive reactions of live tissue to US exposure (e.g., increased temperature and production of reactive oxygen species; Juffermans et al., 2006; Wu, 1998). In the embryonic or newborn mouse, brain ultrasound was nevertheless used to attempt transfection of plasmid DNA in combination with microbubbles, both by intraventricular injection and systemically. However, the transfection efficiency was relatively low, and 50% of the injected embryos suffered from hydrocephaly (Endoh et al., 2002). On the other hand, microbubble-enhanced ultrasound improved gene transfer to the sub-ventricular zone after intraventricular injection in adult mice in vivo (Tan et al., 2016).

3.3. Magnet-assisted transfection

Magnetism-based targeted delivery was first described almost forty years ago (Widder et al., 1978) as a means to use magnetic micro- and nanoparticles for drug delivery to the circulatory system in vivo. The technique takes advantage of a magnetic field to direct magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) containing nucleic acids into the target cells. The MNPs used as carriers are mostly composed of an iron oxide (magnetic) core with an additional organic or inorganic coating (e.g., arabic gum ((Zhang et al., 2009), liposomes (Linemann et al., 2013), polymers, peptides and ligands/receptors (Estelrich et al., 2015)). Coated MNPs have major advantages (Chatterjee et al., 2001; Estelrich et al., 2015). Moreover, due to their positively charged magnetic core, the binding of negatively charged molecules (e.g., DNA) is a relatively fast and easy process. Upon activation of the magnetic field, MNPs are drawn towards the target cells, where they undergo endocytosis or pinocytosis, followed by nucleic-acid release, leaving the membrane composition of the target cell intact (Fig. 2).

In in vitro studies, magnetofection has been commonly used due to its simplicity and high efficiency (Scherer et al., 2002). The application of a magnetic field, together with MNPs, is also a promising approach for in vivo gene transfer due to its noninvasive nature, ability to direct DNA to the region of interest and lack of toxicity. Nevertheless, magnetofection in the CNS is still in its infancy. Indeed, in one report describing MNPs functionalized with PEI that were administered in the rat spinal cord after lumbar intrathecal injection (Song et al., 2010), the experiment was not fully successful due to the dispersion of MNPs in the cerebrospinal fluid after exposure to the magnetic field. On the other hand, highly efficient and long-term magnetofection of complexes of EYFP channelrhodopsin and MNPs for optogenetic applications in the rat visual cortex in vivo has also been reported upon direct brain injection (Soto-Sanchez et al., 2015).

4. Virus-mediated trasduction

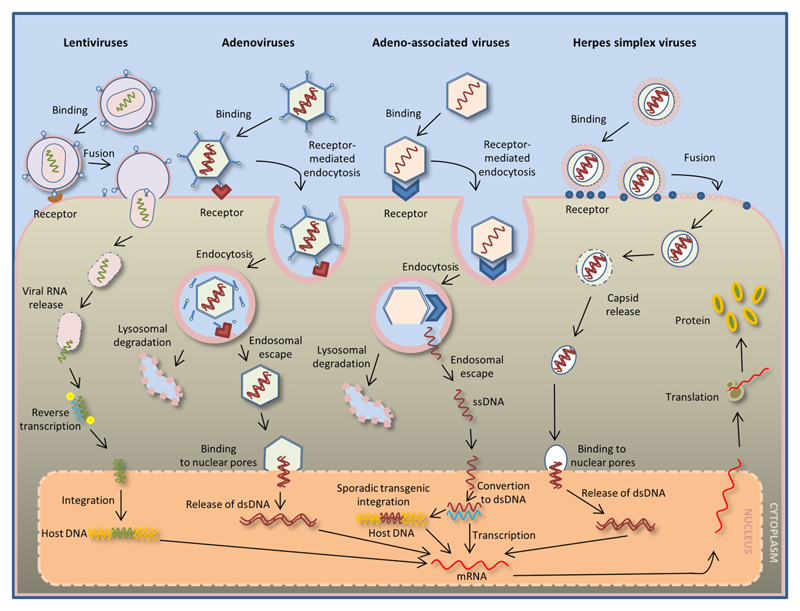

Viruses are nanometric infective agents composed of a protein capsid that protects their genetic material and, in some cases, a lipid envelope derived from the host cell membrane that protects the capsid. Viruses can therefore be classified as naked or enveloped based on the absence or presence of this lipid structure, respectively. All viruses are dependent on the host cell to successfully replicate: they hijack the replication machinery of the host cell and guide it to replicate the viral genetic material. Indeed, during laboratory synthesis of viral particles for experimental applications, cells are first infected with the aim of synthetizing high numbers of new viral particles that are subsequently purified and used at a high concentration in future experiments (Farson et al., 2004). Depending on the type of virus used for the transfection during experimental applications, the genetic material can be integrated in the host DNA or can be temporarily expressed (Fig. 3, Table 3). All cells can be infected by specific viruses (Koonin et al., 2006), and it is the capsid itself or in some cases, the envelope protein sequence and shape that determines what kind of cell a virus will infect, a property called tropism. As the genetic material carried by a virus can be modified or substituted by a synthetic construct altogether, viruses have been widely utilized as a means to perform genetic manipulations in live cells. Interestingly, the capsid can also be artificially modified, thus generating viruses with a desired tropism for specific cell types (Freire et al., 2015).

Fig. 3. Virus-mediated transduction.

A lentivirus (left) can carry RNA inside its capsid. Contact with cell-specific receptors induces the fusion of the capsid with the cell membrane, followed by RNA release. In the cell cytoplasm, the released RNA undergoes reverse transcription, and upon transport to the nucleus, the RNA is integrated with the host DNA. Adenovirus infection (middle left) is mediated by specific receptor binding on the cell membrane, followed by endocytosis. Endosome degradation then results in the release of the virus capsid and lysosomal degradation of the endosome. The released virus capsid binds to the nuclear pore of the infected-cell nucleus, allowing the introduction of the double-stranded DNA inside the nucleus. Adeno-associated virus infection (middle right) is mediated by receptor binding on the host-cell surface and endocytosis. Endosome degradation results in the release of single-stranded DNA. The single-stranded DNA enters the nucleus and undergoes a conversion to double-stranded DNA, which can be either integrated in the host DNA (and later transcribed) or can remain in the host cell nucleus as nonintegrated viral DNA. Herpes simplex virus-mediated gene delivery (right) is the result of receptor binding and fusion of the virus with the cell membrane of the host cell. Inside the cell, the released capsid binds to the nuclear pore and introduces double-stranded DNA into the nucleus to be transcribed. The viral DNA in the host cell nucleus is transcribed into mRNA. The transcribed viral mRNA exits the nucleus, and it is translated into a protein in the cytoplasm of the host cell.

Table 3.

Virus-mediated transduction.

| Group | Type / Helper | Toxicity | In vivo delivery method | Efficiency /Stability | BBB accessibility | Most Prominent Applications (references) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lentivirus | HIV / VSV-G | ↓ | Stereotaxic micro injection | ↑ | N/A | Naldini et al., 1996a; Mah et al., 2002b;Artegiani and Calegari et al., 2013 |

| Adenovirus | Replication-defective ADV | ↑ | Stereotaxic micro injection, Intraventricular injection | ↑ | N/A | Yoon et al., 1996;Germano et al., 2003 |

| Adeno-associated virus | AAV | ↓ | Stereotaxic micro injection | ↑ | N/A | Mah et al., 2000; Kay et al., 2001;Mah et al., 2002a |

| AAV-DJ | ↓ | Stereotaxic micro injection, Intravenous injection | ↑ | + | Grimm et al., 2008; Duque et al., 2009; Foust et al., 2009,Gray et al., 2010; Bourdenx et al., 2014 | |

| Herpes simplex virus | HSV / helper virus | → | Stereotaxic micro injection | ↑ | N/A | Spaete and Frenkel, 1982; Krisky et al., 1998; Sun et al., 2003 |

↑high / →medium / ↓low / +yes / -no / N/A-information not available.

The use of viral vectors for gene delivery into living cells dates back to 1976 when, for the first time, a DNA segment of a bacteriophage lambda was transfected into mammalian cells using a Simian Virus 40 (SV40) vector (Goff and Berg, 1976). Since then, the use of viruses in biological and biomedical research grew exponentially, and today, viral vectors are the most powerful technique for gene delivery in vitro and in vivo. The main advantages of the use of viral vectors are their extremely high specificity towards a certain cellular type and the high efficiency of reliable transfection. On the other hand, once engineered, the viral particle has to be purified. Easy and fast purification protocols are currently available. However, the process may sometimes damage the genomic material (Kay et al., 2001). Moreover, the size of the construct is limited by the packing capacity of the capsid. Furthermore, viruses are administered via intrathecal or intraventricular injection, which is extremely invasive (Artegiani and Calegari et al., 2013; Kotterman et al., 2015a; Thomas et al., 2003). Finally, most viruses require several days before transduction of the genetic material, although the precise expression timing varies for each type of viruses (e.g., herpes simplex peaks at 24 h following infection; adeno-associated viruses require approximately 3 weeks to peak, although the expression is already visible as soon as 24 h following administration; Penrod et al., 2015; Reimsnider et al., 2007). Unlike the other methods for gene delivery, some viral vectors can lead to viral genetic material becoming stably integrated into the host genome (e.g., Herpes Simplex viruses), which makes viral vectors particularly suited for the transfection of dividing cells. On the other hand, integrated viruses may be dangerous because the integration may occur in undesirable zones of the genome, leading to harmful mutations, which hinders their usage in biomedical research (Thomas et al., 2003). Conversely, with some other viral vectors (e.g., adenoviruses), the genetic material remains in the nucleus as a so-called episome. Thus, nonintegrative viruses are safer but are mostly suitable only for nondividing cells, as the nonintegrated plasmid becomes too diluted in rapidly dividing cells to give the desired level of transfection (Kotterman et al., 2015a; Thomas et al., 2003). Here, we will review the four main viral classes that have in vivo applications in basic and biomedical research.

4.1. Lentiviruses

Lentiviruses are enveloped viruses belonging to the class of retroviruses (viruses bearing RNA genetic material) with the unique characteristic of being able to infect nondividing cells in a long-term manner. Being in the class of viruses bearing RNA, these viruses rely on retrotranscription to integrate their genetic material in the host genome (Fig. 3). Retrotranscription involves transcribing RNA into DNA with the help of a reverse transcriptase enzyme, which is encoded by the virus genome. Although lentiviruses are efficient viral vectors used for gene delivery, they were originally derived from pathogenic agents (i.e., human immunodeficiency virus, HIV). This hampers their use in vivo, due to the risks of eliciting strong immunogenic responses or even reconversion to the wild-type pathogenic form (Cockrell and Kafri, 2007; Mah et al., 2002a). One important step made towards the development of safe lentiviral vectors was the substitution of the envelope protein of pathogenic viruses with one derived from a different virus (most commonly, vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein, VSV-G), which cannot successfully multiply after infection of the host cell and presents a wider tropism (Artegiani and Calegari et al., 2013; Mah et al., 2002b). Nevertheless, lentiviruses have been successfully used for efficient gene delivery in vivo for a long time (Bonci et al., 2003; Li et al., 2016; Qiao et al., 2016). Indeed, an HIV-based VSV-G-pseudotyped virus was used for the first time in vivo in 1996 to stably transfect fully differentiated neurons and glial cells and deliver β-galactosidase to the hippocampus of adult rats for up to three months after inoculation, without any evident immunogenic reaction. The stability of the infection depended on integration of the viral genome into the host-cell genetic material (Naldini et al., 1996a, b). Other applications in the CNS followed, and lentiviral vectors injected intracranially were used to study the effect of ApoE isoforms on amyloid plaque deposition in a mouse model, allowing the determination of the isoform-specific effects of ApoE on the amyloid burden in the hippocampus (Dodart et al., 2005). Moreover, modifications of the envelope of lentiviruses allowed preferential targeting of discrete populations of cells in the CNS with high flexibility. For example, lentiviruses pseudotyped with a modified envelope displayed anti-GLAST (an astrocyte-specific protein) IgG on their surfaces and preferential astrocyte targeting in vivo (Fassler et al., 2013). Interestingly, due to their ability to infect fully differentiated cells, lentiviruses find widespread usage in the study and development of therapies for neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s (Azzouz et al., 2004; Bensadoun et al., 2000; Yin et al., 2017) Alzheimer’s (Li et al., 2017; Parsi et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2018) and Huntington’s disease (Cui et al., 2006; Schwab et al., 2017).

4.2. Adenoviruses

Adenoviruses (ADVs) are nonintegrating naked viruses that bear double-stranded DNA. ADVs can transfect dividing and nondividing cells with fairly high efficiency (Mah et al., 2002a). ADVs have been successfully used in vitro to target neocortical and glial cells in culture (Morelli et al., 1999; Smith-Arica et al., 2000; Southgate et al., 2008). Nevertheless, their usage in vivo has been challenging due to their high virulence (Thomas et al., 2003). To overcome this issue, ADVs have been extensively engineered during the last 35 years with the aim of generating nonimmunogenic vectors. The first generation of modified ADVs had their viral genome deleted, generating replication-defective ADVs; nonetheless, these ADVs still exhibited potent T-cell-related immunogenicity. These first-generation viruses showed potent toxicity to the CNS, causing the transfected cells to be phagocyted. Nevertheless, usage of these vectors still led to the successful treatment of glioma in mice (Germano et al., 2003; Immonen et al., 2004; Lentz et al., 2012). Due to their capacity to infect dividing cells, replication-defective ADVs were also used to transfect neuronal precursors in the adult mouse brain following intraventricular injections (Yoon et al., 1996). In a great leap forward, safe ADV vectors were made with the development of helper-dependent ADVs (HD-ADV; Thomas et al., 2003). The HD-ADVs lacked any viral genes; thus, another virus (the helper virus) was needed to carry the information for their replication during the laboratory preparation of viruses for infection. This development enabled the synthesis of viral vectors with the ability to carry long constructs (up to 30 kB) that almost completely lacked virulence. Nevertheless, it is virtually impossible to completely eliminate the helper virus during the laboratory purification procedure, although currently, the amount of contamination can be reduced to less than 0,1%. This is a promising achievement for future studies and applications using HD-ADVs (Kay et al., 2001). Indeed, HD-ADV has been recently used to perform manipulations of the DNA in human pluripotent stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS), opening up the prospect of gene manipulation of pluripotent stem cells for therapeutic applications (Mitani, 2014).

4.3. Adeno-associated viruses

Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are viruses strictly related to ADVs. Indeed, AAVs were first isolated in 1965 as a contaminant in the preparation of ADV (Atchison et al., 1965; Kay et al., 2001). AAVs have a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) genome composed of two genes, one for their replication (rep) and one for their encapsulation (cap), even though AAVs cannot replicate on their own. Similar to ADVs, AAVs require a helper virus to multiply. The AAV genome remains in the nucleus of host cells as an episome, or at a lower frequency, the AAV genome stably integrates in the host genome. The natural replication deficiency of AAVs in the absence of an HV gives them a natural safety mechanism in in vivo applications (Kay et al., 2001; Mah et al., 2002b; Samulski and Muzyczka, 2014; Yan et al., 2005). Indeed, these viruses have never been associated with any pathology, and they are the most studied viral vectors for gene delivery in vivo (Mah et al., 2000). Their main drawback is their small packing capacity (not exceeding 5 kb), which can nevertheless be increased by clever molecular biology tricks (e.g., dividing the expression plasmid into two vectors and reconstituting a fully functional expression cassette after concatemerization of episomes in the nucleus (Thomas et al., 2003)). So far, AAVs are the method of choice for the study of in vivo brain physiology, since the transfection can be stable for strikingly long times. Moreover, different serotypes of AAVs can have different tropisms for discrete cell populations (Burger et al., 2004; Lentz et al., 2012). For example, an AAV infection was stably expressed up to six months in the rat brain (Klein et al., 1999) and up to 6 years in the bone marrow of nonhuman primates (Rivera et al., 2005). Moreover, due to their neurotropism and their ability to be transported along the axon, AAV9 and AAVrh10 may be used for the development of therapeutic approaches for local interventions of axonally connected structures (Choudhury et al., 2016b). Finally, different AAV serotypes can transfect different cell types (e.g., astrocytes and oligodendrocytes) in the brain in vivo (Foust et al., 2009; Lawlor et al., 2009). This transfection was achieved by shuffling random pieces of the cap gene together to generate a large variety of different cap proteins and later screening for specific tropism for different cell types. Indeed, gene shuffling of the heparin-binding domain (HBD) in individual hybrid capsids of various AAV serotypes (AAV-type 2/type 8/type 9 chimera) helped in the creation of the AAV-DJ-derived viral peptide library for cell-specific tropism in vivo in mice (Grimm et al., 2008). The effect of the HBD on viral tropism was demonstrated by transduction to diverse tissues, including the brain (Grimm et al., 2008). Notably, cap-gene shuffling was also used to develop chimeric AAVs with the remarkable ability to pass through the seizure-compromised BBB in rats after kainic acid-induced seizures (Gray et al., 2010). In addition to capsid shuffling, packaged plasmids with specific promoters can also be used to achieve the goal of cell specificity (see the discussion section for further information about promoters). Interestingly, other AAV serotypes -when administered intravenously - were unexpectedly shown to cross even an intact BBB in young and adult animals (Bourdenx et al., 2014; Duque et al., 2009; Foust and Kaspar et al., 2009; Foust et al., 2009). All these findings further fuel the interest in basic and biomedical research on AAVs.

4.4. Herpes simplex viruses

The herpes simplex viruses (HSVs) are enveloped viruses bearing double-stranded DNA genetic material. Their genome is relatively large, having a length of approximately 152 kb and containing more than 80 genes. Because many of the genes are not essential for viral replication, HSVs can carry at least 30 kb of nonviral DNA suitable for experimental purposes (Kay et al., 2001). The main advantages of HSVs are their high tropism for the CNS (for an unknown reason, especially sensory neurons; Menendez and Carr, 2017) and the fact that after infection, the HSV genome mostly remains in a latent form as a stable circular episome in the nucleus of fully differentiated cells for a very long time without eliciting any immunogenic response (Lentz et al., 2012). On the other hand, their strikingly complex envelope makes the development of cell-specific HSVs very challenging, although pseudotyping of HSV with the VSV-G protein can reduce off-target transfection in vitro (Andersen et al., 1982). Moreover, HSVs may still cause a massive activation of the immune system by starting replication in the host cell. This activation remains one of the main concerns for the use of HSV for gene delivery in vivo. One way to avoid self-replication is to delete some of the viral genetic material, generating nonself-replicating viral particles, which nevertheless need to be coupled to helper viruses for their replication during preparation (Kay et al., 2001; Spaete and Frenkel, 1982). With this process, cytotoxicity was strongly reduced, and neurons in culture were stably transfected for more than three weeks (Krisky et al., 1998). Although HSVs have been widely studied in vivo to treat glioblastoma in rodents (Nakashima et al., 2018; Ning and Wakimoto, 2014; Wollmann et al., 2005), their application to the transduction of neurons is still limited. Nevertheless, HSVs have been already used to transfect the striatum (for up to 7 months) in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease with genes necessary for the functioning of dopaminergic neurons, providing significant recovery of the phenotype (Sun et al., 2003).

5. Discussion

5.1. Challenges of in vivo gene delivery to the brain

The study of the CNS through acute genetic manipulations in vivo to understand brain function in health and disease has always been a challenging issue for scientists. First, there are technical issues related to the inaccessibility of the brain due to the presence of the skull and the BBB. Additionally, the great complexity of brain circuits (i.e., the variety of neuronal and nonneuronal cell types) and network functionality (i.e., the long- and short-range connectivity among different brain regions) renders it difficult to establish causal relationships between genetic manipulations and cellular/behavioral outcomes in basic research. Finally, the invasiveness of surgical procedures and viral vector safety constitute additional challenges for translational applications. The various methods for in vivo gene manipulations highlighted above present positives and negatives in regard to applications for basic research or translational purposes in the difficult to access brain, which we will discuss below.

5.1.1. CNS penetration

The first difficulty in achieving acute gene manipulations in the brain in vivo is the need to bypass the skull or the BBB. To this end, tremendous efforts have been made to improve brain-delivery methods or maximize vector permeability. One of the first and simplest ideas developed in the past was the injection of DNA directly into the brain area of interest. The first studies in this regard were performed in the late 1980s and early 1990s (Breakefield and Geller, 1987), when different groups performed genetic manipulations by viral injection directly into the rodent retina and brain (Davidson et al., 1993; Palella et al., 1989; Price et al., 1987). Furthermore, lipofectin-supported DNA transfection, which overcomes the electrostatic repulsion of DNA by the cell membrane, was also successfully performed by direct injection into the mouse brain (Ono et al., 1990). Subsequently, chemical polymers such as PEI were used to directly inject genetic material into the cortex, hippocampus (Abdallah et al., 1996), spinal cord (Shi et al., 2003), and SVZ (Lemkine et al., 2002) of rodents. Moreover, lipid vectors were also effectively injected in the ventricles of early postnatal mice (Hassani et al., 2005; Roessler and Davidson et al., 1994) for basic research or in rodent glioblastoma to investigate possible therapeutic approaches (Cikankowitz et al., 2017; Lagarce and Passirani, 2016; Pulkkanen and Yla-Herttuala, 2005). Currently, physical methods, such as IUE and EUE, are particularly suitable for studies of neurodevelopment, as DNA can be directly injected into the large ventricles of developing embryos and a strong electric field can be easily applied to the head of the embryos. Indeed, embryos have no bony skull, which guarantees high transfection efficiency (Saito, 2006; Szczurkowska et al., 2016). Moreover, the quick expression of transfected genetic material upon electroporation also contributes to the successful application of this technique for neurodevelopmental studies. On the other hand, for viral vectors, the main strategy used for their delivery in the brain remains the direct intraparenchymal infusion of viral particles. Indeed, ventricle injection requires a large quantity of viral material at high concentrations, which may be difficult to obtain, as well as costly. Thus, viral injection is more suitable for local transfection in the postnatal and adult brain. Moreover, unlike electroporation, which becomes difficult when the electric field needs to be delivered through the bony skull of an adult animal, small amounts of viral vectors can be delivered by direct stereotaxic injection in a specific brain region of adult animals, following a minor craniotomy. Thus, viral vectors are the technique of choice for the study of brain functionality at later postnatal ages, which is also compatible with the fact that these vectors may require days before driving efficient expression of the genetic material that they carry.

Since direct injection in the brain - especially when considered for translational applications - is still an invasive technique due to the procedure itself and the risks of possible side effects related to the surgical intervention, new strategies have been developed to bypass the BBB in recent years. In particular, lipids and polymers supplemented with helper lipids or functionalized with peptides to increase their BBB permeation were successfully used with intravenous injection. For example, dendrimers, PEI and nanoparticles have been functionalized with PEG and other organic molecules to enable them to cross the BBB (Zarebkohan et al., 2015). In addition, viral capsids have been engineered to be more BBB permeable (Choudhury et al., 2016a, c; Deverman et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2011). Moreover, a portion of the produced AAV particles remain associated with cell membranes (exosome-AAVs). Compared with AAVs, exosome-AAVs have a longer half-life in the blood and increased BBB permeability (Hudry et al., 2016; Maguire et al., 2012). Alternatively, nanoparticles have been conjugated to genetic material, and their small dimensions allow direct intranasal delivery; thus, this method guarantees direct brain access because it does not require BBB crossing (Yadav et al., 2016).

5.1.2. Transfection specificity in the brain

Another open issue to address when studying brain function and possibly conceiving new treatments for brain disorders is the complexity of brain networks: the ability to transfect a precise cell population among many others has always been a challenge. The possibility of directing the electric field and thus the DNA in a specific direction allowed the easy transfection of discrete populations of neuronal progenitors of specific brain areas by IUE and EUE (dal Maschio et al., 2012; Saito, 2006; Saito and Nakatsuji, 2001; Szczurkowska et al., 2016). Nevertheless, while this method is very useful for in vivo developmental studies, it is less suitable for studies performed in adult animals, where chemical methods or viruses are the method of choice. With these chemical or viral methods, the selection of an appropriate cell-specific promoter upstream of the gene of interest enables the transfection of discrete cell types (Murlidharan et al., 2014; Ojala et al., 2015). For this purpose, several neuron- and glial-specific promoters have been identified and tested for their ability to enable cell-specific transduction (Hashimoto et al., 1996; Miura et al., 1990; Morelli et al., 1999; Oellig and Seliger, 1990; Quinn, 1996). Nevertheless, the cell-specific promoters tend to be too large to be packaged into viral vectors, and the resulting gene expression is weaker than that driven by constitutive viral promoters (e.g., CMV; Hioki et al., 2007; Shevtsova et al., 2005). Thus, novel, smaller hybrid promoters that are able to efficiently induce a strong, specific gene expression pattern have been generated (Gray et al., 2011; Hioki et al., 2007; Kugler, 2016).

5.1.3. Combinations of the diverse in vivo transfection methods

To try and further overcome the difficulties related to modulation of gene expression in vivo in the CNS in terms of brain accessibility, transfection efficiency and/or space and time specificity, coupling of the different delivery techniques has offered unquestionable advantages. For example, BBB opening by focused US was combined with systemic administration of DNA bound to nanoparticles, resulting in a noninvasive strategy for achieving safe, highly localized, robust, and sustained transgene expression in the CNS (Mead et al., 2016). Moreover, a combination of US with the intravenous administration of naked microbubbles - together with naked plasmid DNA (Shimamura et al., 2004), AAVs (Hsu et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2017), liposomal-plasmid DNA (Lin et al., 2015), liposome-shRNA-NGR complexes (Zhao et al., 2018), polyethylene glycol-modified lipid-based bubbles (Negishi et al., 2015), or folate-conjugated gene-carrying microbubbles (Fan et al., 2016) - can induce reversible openings in the BBB and can increase the transfection efficiency in rodents. Furthermore, a more efficient, brain area-specific infection was achieved by coupling adenoviral vectors with magnet-assisted transfection in the brain of rodent embryos in utero (Hashimoto and Hisano, 2011; Sapet et al., 2012).

5.1.4. Combinations of in vivo transfection methods with newly emerging techniques

The coupling of molecular biology tools, including newly emerging techniques, with techniques for gene delivery in vivo also has tremendous potential. For example, to achieve a transfection that is better confined in time and space, IUE was coupled to the Cre/loxP system in the study of retinal development (Matsuda and Cepko et al., 2007), and AAV transfection was coupled to the tetracycline-controlled transcriptional activation system (tet-on/off) in the study of the structure of the neural circuits in the mouse neostriatum and primary somatosensory cortex (Sohn et al., 2017). Moreover, both viral vectors and/or IUE were successfully used to introduce optogenetic proteins, chemogenetic receptors or voltage sensors into specific cell-types, cortex layers or brain areas, allowing the study of neural circuits in vivo (Ghitani et al., 2015). Furthermore, CRISPR-Cas9 technology, which allows genome editing, regulation and visualization (Gilbert et al., 2013; Mali et al., 2013; Qi et al., 2013), was recently coupled to IUE to study the role of specific genes in brain development in vivo by knockout (Chen et al., 2015; Cheng et al., 2016; Kalebic et al., 2016; Rannals et al., 2016a, b; Shinmyo et al., 2016; Straub et al., 2014; Wang, 2018) or knock-in (Tsunekawa et al., 2016). CRISPR-Cas9 technology coupled to IUE also enabled the study of the subcellular localization of specific proteins by inserting a sequence for a fluorescent protein into their encoding gene (Mikuni et al., 2016). Moreover, CRISPR-Cas9, despite its large size, can be packaged in viral vectors for in vivo delivery, thus enabling robust transfection in the adult mouse brain (Chen and Goncalves, 2016; Chew et al., 2016; Ortinski et al., 2017; Schmidt and Grimm, 2015). Interestingly, to increase Cas9 editing efficiency and decrease the risks of off-target effects, different groups tested the delivery of a protein Cas9-guide RNA (gRNA) complex by nucleofection (Kim et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2014), cationic lipids (Zuris et al., 2015), lipid nanoparticles (Wang et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2016) and cell-penetrating peptides (Ramakrishna et al., 2014) in mammalian cells in vitro, thus opening the possibility of a new delivery strategy to be applied in vivo. Indeed, the protein Cas9/gRNA complex was recently coupled to IUE to study the effect of the Tbr2 knockout in mouse neocortical progenitors (Kalebic et al., 2016) and was injected in the hippocampus, dorsal striatum, primary somatosensory cortex and primary visual cortex of adult mice with a positive outcome (Staahl et al., 2017).

5.2. Specific challenges for translational research and possible therapeutic applications

Gene therapy is defined as the transfer of genetic materials to specific target cells of a patient with the final goal of preventing or rescuing a particular disease state (Mali, 2013). The main strategies for gene therapy utilized so far entail the introduction of a replacement allele into cells to compensate for the loss of function of a gene, the silencing of a dominant mutant pathological allele and the introduction of trophic factors or compensatory proteins (Choudhury et al., 2016c). The first gene delivery in the human brain was performed by stereotactic injection of retrovirus- and ADV-containing nuclear-targeted β-galactosidase cDNA in 10 patients with malignant glioma (Puumalainen et al., 1998). For the first time, this study evaluated the feasibility and safety of virus-mediated gene transfer in human glioma in vivo, and it showed a positive outcome (Puumalainen et al., 1998). Since then, due to the therapeutic benefits and the safety found in subsequent clinical trials, gene therapy has become a possible option for clinical intervention in some otherwise terminal or severely disabling conditions (Naldini, 2015). Indeed, in recent years, a large effort has been put into continuously improving gene-delivery methods, and currently, more than 2000 approved gene-therapy clinical trials have been conducted or are ongoing worldwide (http://www.abedia.com/wiley/).

However, the vast majority of the gene-therapy clinical trials so far have addressed cancer (64,5%), with neurological diseases representing only 1.8% of the studies (http://www.abedia.com/wiley/). On the one hand, this scarcity may be because the neuropathological mechanisms underlying several neurological disorders are still poorly understood. In this respect, in vivo methods for gene delivery that have been discovered by emerging basic research may also hold great potential in the long run for increasing our understanding of brain pathology. On the other hand, the low number of gene-therapy clinical trials for brain disorders may be due to the low availability of safe and efficient delivery vectors that can cross the BBB or can be directly injected in the brain without major complications. Nevertheless, the increasing prevalence of some neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., autism spectrum disorders; Neggers, 2014) and of neurodegenerative disease (due to the increase in the average age of the population; Johnson, 2015), in combination with the identification of clearly causative mutations and the paucity of standard pharmacological treatments for these brain disorders, highlights the need to search for alternative therapeutic approaches, including gene therapy. Currently, AAV vectors have become the vehicle of choice for in vivo gene transfer in most of the clinical trials targeting the brain. Nevertheless, although some AAVs that are being currently tested in animal models can effectively cross the BBB (Choudhury et al., 2016b, c; Deverman et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2011), so far, the AAVs used in clinical trials are less permeable. Therefore, these AAVs are commonly injected directly into the brain parenchyma, nevertheless enabling long-term, relatively safe expression (Choudhury et al., 2016c). For example, an ongoing phase I/II study is testing intraputaminal brain infusion of an AAV encoding human aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase as a possible treatment in subjects with Parkinson’s disease (http://www.abedia.com/wiley/). Interestingly, AAVs were recently engineered to be able to efficiently transduce neural stem cells (Choudhury et al., 2016b; Kotterman et al., 2015b). To avoid the risk of the surgery-related side effects of classic parenchymal injection for virus delivery, a less invasive method, such as administration into the cerebrospinal fluid via intracerebroventricular (ICV) or intrathecal (IT) injection, has also been proposed (Choudhury et al., 2016c). Nevertheless, these methods of application seem to be less effective in bypassing the BBB and less safe due to the activation of immunogenic responses (Choudhury et al., 2016c).