Abstract

Intranasal insulin has shown effficacy in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but there are no preclinical studies determining whether or how it reaches the brain. Here, we showed that insulin applied at the level of the cribriform plate via the nasal route quickly distributed throughout the brain and reversed learning and memory defficits in an AD mouse model. Intranasal insulin entered the blood stream poorly and had no peripheral metabolic effects. Uptake into the brain from the cribriform plate was saturable, stimulated by PKC inhibition, and responded differently to cellular pathway inhibitors than did insulin transport at the blood-brain barrier. In summary, these results show intranasal delivery to be an effective way to deliver insulin to the brain.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, cognition, insulin, intranasal administration

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other related forms of dementia have become one of the most severe socioeconomic and medical burdens impacting modern society. Currently there are an estimated 44 million people worldwide suffering from AD or other dementias. With the aging human population, this number is expected to double by 2030 and more than triple by 2050. Huge efforts are being made toward the development of therapeutic strategies to delay the onset and progression of AD in order to signifficantly reduce the economic and medical burden caused by this disease.

One therapeutic approach that has shown promise in treating individuals with AD is the use of intranasal insulin. Modiffications in brain insulin metabolism are thought to be a pathophysiological factor underlying this neurodegenerative disorder [1, 2]. In support of this hypothesis, studies have demonstrated that patients with AD have reduced brain insulin receptor sensitivity [3, 4], hypophosphorylation of the insulin receptor and downstream second messengers such as insulin receptor substrate-1 [4, 5], and attenuated insulin and insulin-like growth factor receptor expression [5]. Insulin has a number of important functions in the central nervous system (CNS). Insulin receptors in the brain are located in the olfactory bulb, hypothalamus, hippocampus, cerebral cortex, and cerebellum [6] and are found primarily in synapses, where insulin signaling contributes to synaptogenesis and synaptic remodeling [7]. Acute delivery of insulin to the hippocampus improves spatial memory in a PI3K-dependent manner by modulating glucose utilization [8]. Administration of insulin, either intranasally or by perfusion, to healthy individuals improved their cognitive function [9, 10]. Intranasal insulin administration prior to anesthesia is capable of preventing AD-like tau hyperphosphorylation in 3xTg-AD mice, a commonly used transgenic model of AD [11]. Tau hyperphosphorylation, a pathological hallmark of AD, is increased with anesthetic exposure [12] and can cause significant learning and memory defficits in aged rodents [13, 14]. As enhanced brain insulin signaling improves memory processes in cognitively healthy humans and possesses neuroprotective properties, it was hypothesized that increasing brain insulin concentrations in AD patients would prevent or slow the development of this devastating disease.

Intranasal insulin administration has been shown to be an effective therapeutic treatment for improving cognition in patients with AD. A clinical study was completed on patients with AD or amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [15]. In this study, the patients received either placebo or 20 or 40 IU of insulin administered intranasally over the course of 4 months, and a small subset of patients were involved in a positron emission tomography (PET) study before and after they received the intranasal insulin treatment. Results from this study indicated an improvement in delayed memory and cognitive function, using outcome measures such as delayed story recall and Alzheimer Disease’s Assessment Scale-cognitive sub-scale. Results from the PET data indicate an increase in18F fluorodeoxyglucose in the parietotemporal, frontal, precuneus, and cuneus regions of the CNS following intranasal insulin administration when compared to the placebo controls, thus linking the improvement in cognitive function to processes in these brain regions. Studies have shown that a single dose of intranasal insulin acutely improved memory in memory-impaired older adults with AD or MCI and also improved memory and cognitive function with multiple treatments of patients with AD and MCI [16]. Insulin was effective in improving performance on a verbal memory test in a group of AD and MCI patients; however, within these groups patients who were APOE ε4 positive or female showed poorer recall following insulin administration compared to patients who did not possess this allele and males [17]. Similar results were found with rapid-acting insulin, which is thought to have superior effects intranasally when compared to regular insulin, in APOE ε4 positive AD patients [18].

The clinical research conducted thus far is promising because improvements of cognitive memory processes induced by insulin have been discovered; however, further clinical trials are needed to assess the clinical relevance of intranasal insulin in the treatment of cognitive disorders. In addition, very little is known about the mechanism by which intranasally administered insulin reaches the brain. Some hypotheses by which intranasally administered insulin reaches the brain from the nasal passage include transport along the axon bundles of the olfactory receptor cells in the roof of the nasal cavity, transport along the trigeminal neural pathway, and transport via the rostral migratory stream[19].More recently, studies have shown that the rapid distribution of intranasally administered molecules through the olfactory pathway or the trigeminal pathway involves bulk flow within the perivascular space of cerebral bloodvessels[20]. In this study we hope to elucidate the mechanism(s) by which intranasally administered insulin is transported across the nasal epithelium. Here, we examine the regional distribution and time course of administered insulin, explore the cellular mechanisms of brain uptake and assess the effects on cognition in a mouse model of AD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male CD-1 mice, 8 weeks of age, purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA), were used for all experiments, except for the cognition experiments. For cognitive studies we used 12-month-old SAMP8 mice from our in house colony (St. Louis VA). Mice had ad libitum access to food and water and were placed on a 12-h light/dark cycle. All studies were performed under approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols and by an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International accredited facility.

Radioactive labeling of insulin

Human recombinant insulin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was radiolabeled with 125I using the chloramine T method [21]. Briefly, 10 μg of insulin (dissolved in 0.25 M chloride free phosphate buffer) was mixed with 40 μl 0.25 M phosphate buffer, 1.43 μl 125I (0.5 mCi; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA), and 10 μl chloramine T (1 μg/μl). The reaction was terminated after 1 min incubation at room temperature with 10 μl sodium metabisulffite (10 μg/μl). The free 125I was removed from the sample using a Sephadex G-10 column (Sigma-Aldrich). Fractions were collected in 100 μl lactated Ringer’s (LR) solution in glass culture tubes previously coated with Sigmacote® (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO) to prevent sticking of the peptide. To assess the stability of 125I-insulin, an aliquot of the labeled peptide fraction was precipitated in 15% trichloroacetic acid. All iodinated proteins showed greater than 90% activity in the precipitate.

Intranasal administration

CD-1 mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal (ip) injection of 40% urethane solution (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO). Mice were given an intranasal administration of 1 μl of 400,000 cpm/μl 125I-insulin in LR. The 1 μl was delivered to the cribriform plate by using a 10 μl tip (FB Miniflex tip 0.1–10 μl round 0.06 mm; ThermoFisher Scientiffic, Waltham, MA) inserted 4 mm into the left naris of the mouse.

Tissue collection

CD-1 mice were anesthetized and administered 125I-insulin intranasally as described above. Blood was collected from the right carotid artery and the whole brain was removed at 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 30, 45, and 60 min (n = 5 mice/time point) post intranasal administration. The brain was dissected following the method of Glowinski and Iversen [22] on ice into the olfactory bulb, and ffive brain regions: cortex, hypothalamus, hippocampus, cerebellum, and the remainder. The whole blood was centrifuged at 5000×g for 10 min at 4°C and the amount of radioactivity was measured in 50 μl of the resulting serum. The amount of radioactivity in each of the brain regions and the serum was measured in a gamma counter by counting for 30 min. The percentage of the injected dose present in a milliliter of serum (%inj/ml) was calculated with the following equation:

where Inj is the cpm administered and cpm/ml is the level of radioactivity in a ml of serum. The percentage of injected dose taken up per gram of brain region (%inj/g) was calculated at each time point using the following equation:

where W is the weight of the given brain region in grams, and cpm-R is the level of radioactivity in the brain region. This calculation has been described previously [23].

Saturation study of intranasally injected insulin

CD-1 mice were anesthetized and administered 400,000 cpm of 125I-insulin in the presence or absence of 1 μg of cold insulin intranasally to the cribriform plate of the left naris. Blood was collected from the right carotid artery and the whole brain was removed 15 min (n = 45 mice) post intranasal administration. The brain was then dissected and separated into four regions: olfactory bulb, cortex, cerebellum, and remainder. The whole blood was centrifuged at 5000×g for 10 min at 4°C and the amount of radioactivity was measured in 50 μl of the resulting serum. The amount of radioactivity in each of the brain regions and the serum was measured in a gamma counter by counting for 30 min. Calculations of %inj/g and %inj/ml were done as described above.

Cellular mechanisms study

CD-1 mice were anesthetized and administered a 1 μl solution containing one of the following metabolic inhibitors: LY294002 (50 μM in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO); Sigma-Aldrich), phenylarsine oxide (100 μM in DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich), lidocaine (1% solution in methanol (MeOH); Sigma-Aldrich) histamine (100 ng/mL in MeOH; Sigma-Aldrich), ffilipin (5 μg/mL in DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich), phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (100 ng/mL in DMSO: Sigma-Aldrich), verapamil (10 μM in MeOH; Sigma-Aldrich), or monensin (50 μM in MeOH; Sigma-Aldrich) was intranasally administered to the cribriform plate of the left naris. There were 10 mice injected per drug group. As a control, 1 μL of the vehicle used to deliver the drugs—either DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) or MeOH (ThermoFisher Scientiffic)—was injected into the left naris to the depth of the cribriform plate (4 mm). Each drug group was done concurrently with a control group. 30 min after intranasal injection of the metabolic inhibitor or control, 400,000 cpm of 125I-insulin was injected into the left naris (1 μL volume for intranasal studies) or into the left jugular vein (200 μL volume for intravenous studies). Blood was collected from the right carotid artery and the whole brain was removed 15 min after the intranasal 125I-insulin administration. The brain was then dissected and separated into four regions: olfactory bulb, cortex, cerebellum, and remainder. The whole blood was centrifuged at 5000×g for 10 min at 4°C and the amount of radioactivity was measured in 50 μl of the resulting serum. The amount of radioactivity in each of the brain regions and the serum was measured in a gamma counter by counting for 30 min. Calculations of %inj/g and %inj/ml were done as described above.

Simultaneous injection of inhibitor and 125I-insulin

CD-1 mice were anesthetized and a 1 μl solution containing either LY294002 (50 μM in DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich) or PMA (100 ng/mL in DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich) was intranasally administered to the cribriform plate of the left naris. As a control, 1 μL of the vehicle (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich) was injected into the left naris to the depth of the cribiform plate (4 mm). Immediately after administration of the inhibitor or the control, 400,000 cpm of 125I-insulin (1 μl) was injected into the left naris. A solution containing both the inhibitor and the 125I-insulin could not be prepared due to the solubility of these compounds. 15 min after administration, blood was collected from the right carotid artery and the whole brain was removed. The brain was then dissected and separated into four regions: olfactory bulb, cortex, cerebellum, and remainder. The whole blood was centrifuged at 5000×g for 10 min at 4°C and the amount of radioactivity was measured in 50 μl of the resulting serum. The amount of radioactivity in each of the brain regions and the serum was measured in a gamma counter by counting for 30 min. Calculations of %inj/g and %inj/ml were done as described above.

T-Maze assessment of memory

The T-maze, a reference-memory task, which tests hippocampal dependence of memory, was utilized on the SAMP8 mouse model to investigate changes in memory after intranasal administration as previously described [23, 24]. Briefly, mice were placed in the apparatus and trained until they made a single avoidance. Retention was tested one week later by continuing training until mice reached the criterion of ffive avoidances in six consecutive trials. The results were reported as the number of trials to criterion for the retention test. Prior to intranasal insulin administration, the mouse was anesthetized in an induction chamber using 4% isoflurane delivered via a precision vaporizer with appropriate waste gas scavenging. A 0.5 to 2.5 μl pipette with an electrophoresis or gel-loading tip was used to administer the test agent. One μl of test agent was drawn up into the pipette tip, the outside surface of the tip was coated with lubricating jelly, then while holding the anesthetized mouse in a supine position, the pipette tip was gently placed into the right naris at distance of 4–5 mm and the agent evacuated from the tip. The mouse was returned to its home cage until testing. Mice were treated in three different learning and memory paradigms. In the ffirst paradigm, mice were treated with saline or insulin either immediately after acquisition or 24 h after acquisition. In this case, only the effect on retention and not acquisition was measured. In the second paradigm, mice were treated 24 h before acquisition and were then tested for retention 7 days after that. In the third paradigm, mice were treated with insulin 7 days before acquisition; in this case, both acquisition and retention were tested.

Object recognition

Novel object-place recognition is a declarative memory task involving the hippocampus when the retention interval is 24 h after initial exposure to the objects [25].SAMP8 mice were subjected to object recognition testing to determine the effects that intranasal insulin administration had on changes to declarative memory as previously described [26, 27]. Briefly, SAMP8 mice were habituated to an empty apparatus prior to training. During the training session, the mouse was exposed to two alike objects (plastic frogs), which it was allowed to examine for 5 min. After training, the SAMP8 mice were administered intranasal insulin as described above. Mice were administered either a single dose of insulin or multiple doses. Multiple dosing occurred every 48 h until7 doses were administered. 24 h after the last insulin administration, the mouse was exposed to one of the original objects and a new novel object in a new location and the percent of time spent examining the new object was recorded. The underlying concept of the task is based on the tendency of mice to spend more time exploring new, novel objects than familiar objects. Thus, the greater the retention/memory at 24 h, the more time spent with the new object. The value is presented as the discrimination index, which is determined by dividing the time spent exploring the novel object by the total exploration time multiplied by 100.

Comprehensive lab animal monitoring system (CLAMS)

Metabolic parameters, physical activity, and food intake were measured using a comprehensive laboratory animal monitoring system (CLAMS; Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) as previously described [28]. Male CD-1 mice were monitored for 48 h in individual cages, with a 12 h light/dark cycle at thermoneutrality (30°C). Mice were monitored for 24 h to establish a baseline before intranasal administration of insulin or vehicle control. A single dose of 0.1 μg/μl insulin or vehicle was administered 24 h after mice were placed in the CLAMS cages by using isoflurane to anesthetize the mice for intranasal injection. The mice were monitored for an additional 24 h post intranasal administration. Open-circuit indirect calorimetry was used to measure oxygen consumption (VO2) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2) in 20-min intervals. Respiratory quotient (RQ), which is a measurement of metabolic substrate utilization, was calculated by the ratio of VCO2/VO2. An RQ of 0.7 indicates preferential utilization of lipids, while an RQ of 1.0 indicates preferential use of carbohydrates; intermediate RQ indicated mixed fuel utilization. The Lusk equation, VO2 × (3.815 + 1.232 RQ), was used by the CLAMS software to calculate energy expenditure. Energy expenditure is expressed in kilocalories per hour. Food intake was monitored continuously throughout the study by measuring disappearance of food from feeders placed on Mettler balances. Total physical activity was measured continuously by infrared beam-breaks at a height of 1 inch above the cage floor. Ambulatory activity was deffined as two or more sequential horizontal beam breaks.

Statistical analysis

Means are reported with their standard errors. More than two means were compared by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Newman-Keuls post-test. Statistical signifficance was taken as p < 0.05. The Prism 5.0 statistical software program (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) was used in statistical analysis.

RESULTS

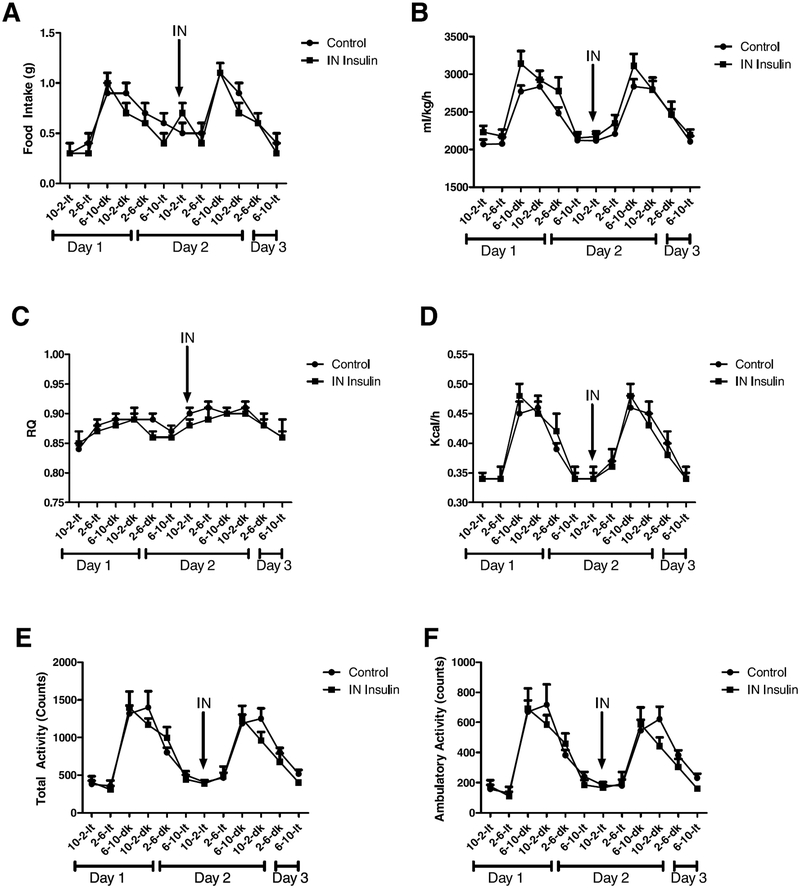

Metabolic activity of CD-1 mice after intranasal insulin administration

Male CD-1 mice were placed in CLAMS cages and monitored for 24 h to establish baseline metabolic activity. Once baseline was established, a single administration of 0.1 μg/μl insulin or vehicle control was administered and the animals monitored for a further 24 h. No statistical signifficance was observed in any of the measures of metabolic activity including respiratory quotient, total activity, ambulatory activity, and energy expenditure (Fig. 1A–F). A mild decline in food intake was observed after intranasal administration but was not statistically signifficant (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Metabolic activity of CD-1 mice post intranasal insulin administration. Male CD-1 mice were placed in a comprehensive lab animal monitoring system for 24 h to establish baseline. A single dose of 0.1 μg/μl insulin was administered intranasally and the animals monitored for an additional 24 h. Measurements were taken for food intake (A), oxygen consumption (ml/kg/h) (B), respiratory quotient (C), energy expenditure (kcal/h) (D), total activity (E), and ambulatory activity (F). No signifficant difference was observed between the vehicle control and insulin treated mice.

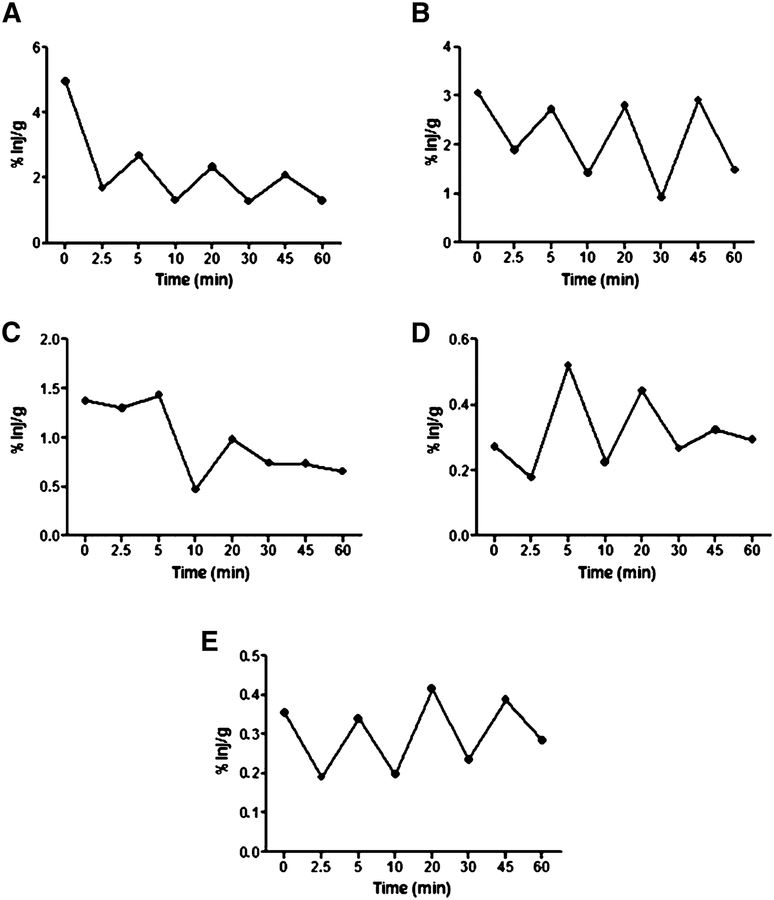

Distribution of 125I-insulin in the brain after intranasal injection

Intranasal insulin was administered to male CD-1 mice for a time course between 2.5–60 min, and brains were dissected into the following regions: olfactory bulb, hypothalamus, hippocampus, cerebellum, and remainder, which were used to calculate the whole brain values. Figure 2 shows the percent of intranasal insulin administered taken up per gram of brain region (%inj/g). All brain regions analyzed showed uptake of 125I-insulin. Each region showed rapid uptake after intranasal insulin administration. At 60-min post administration, the 125I-insulin signal was still present in all the brain regions.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of 125I-insulin in the brain after intranasal administration. Appearance of 125I-insulin in the olfactory bulb (A), hypothalamus (B), hippocampus (C), cerebellum (D), and whole brain (E) at 2.5 (n = 6), 5 (n = 5), 10 (n = 5), 20 (n = 5), 30 (n = 5) 45 (n = 6), and 60 (n = 6) min after intranasal administration.

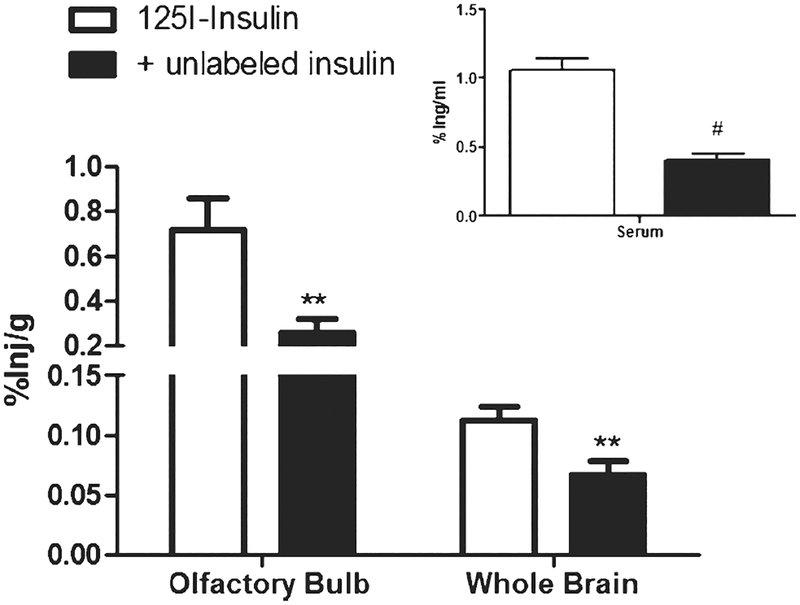

Saturation of intranasal insulin uptake into the brain

To determine if insulin transport across the cribriform plate into the brain was a saturable system, 125I-insulin was administered intranasally in the presence of unlabeled insulin. Male CD-1 mice were given an intranasal injection of 125I-insulin in the presence or absence of unlabeled insulin. After 30 min, serum was collected and the brain dissected into four regions which were used to assess whole brain changes. Administration of the unlabeled insulin led to a signifficant decrease in insulin uptake in the olfactory bulb (0.715±0.139 %inj/g to 0.26±0.061 %inj/g; p = 0.0039) and the whole brain (0.1123±0.0117 to 0.06675±0.0112; p = 0.0067) (Fig. 3). There was no change observed in the cerebellum (0.124±0.023 %inj/g to 0.155±0.043 %inj/g). There was a significant decrease in the amount of radioactively labeled insulin in the cortex (0.1107±0.0107 %inj/g to 0.0514±0.013 %inj/g; p = 0.0008) and the serum (1.061±0.082 %inj/ml to 0.406±0.045 %inj/ml; p < 0.0001).

Fig. 3.

Saturability of 125I-insulin in the brain. %Inj/g of 125I-insulin ± unlabeled insulin in olfactory bulb and whole brain 30 min after intranasal administration. Inset shows %inj/ml for serum at 30 min after intranasal administration. Unlabeled insulin produced signifficant decreases in the olfactory bulb (**p = 0.0039; n = 45), whole brain (**p = 0.0067; n = 45), and serum ((#p < 0.0001; n = 45) as assessed by t-test.

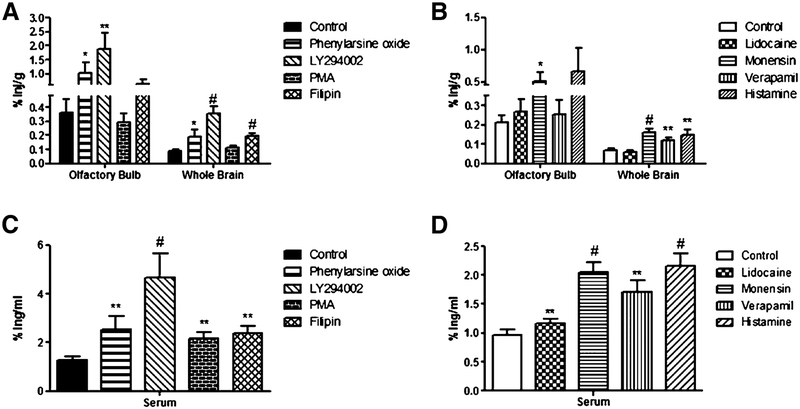

Inhibitors of cellular mechanisms result in increased insulin uptake

To determine the mechanism of action of intranasal insulin transport, male CD-1 mice were administered an inhibitor to block various aspects of protein transport. Prior to the administration of intranasal insulin, CD-1 mice were treated for 30 min with an intranasal injection of one of the following substances: 50 μM LY294002, 100 μM phenylarsine oxide, 1% lidocaine solution, 100 ng/ml histamine, 5 μg/ml ffilipin, 100 ng/ml PMA, 10 μM verapamil, or 50 μM monensin. As controls, mice were given an intranasal injection of a vehicle (MeOH or DMSO) corresponding to the solubility of each substance. The amount of 125I-insulin was measured in various regions of the brain (olfactory bulb, cerebellum, cortex, or remainder) and in the serum (Fig. 4). Treatment with phenylarsine oxide (0.3597±0.098 %inj/g to 1.035±0.035 %inj/g; p = 0.0206), LY294002 (0.3597±0.098 %inj/g to 1.883±0.5619 %inj/g; p = 0.0006), and monensin (0.2107±0.038 %inj/g to 0.5119±0.1405 %inj/g; p = 0.0121) led to a significant increase in insulin uptake in the olfactory bulbs. Treatment with phenylarsine oxide (0.0908±0.0113 %inj/g to 0.187±0.0557 %inj/g; p = 0.0206), LY294002 (0.0908±0.0113 %inj/g to 0.3525±0.051 %inj/g; p < 0.0001), filipin (0.0908±0.0113 %inj/g to 0.1929±0.0223 %inj/g; p = 0.0001), monensin (0.0671±0.009 %inj/g to 0.1622±0.016 %inj/g; p < 0.0001), verapamil (0.0671±0.009 %inj/g to 0.1177±0.017 %inj/g; p = 0.0079), and histamine (0.0671±0.009 %inj/g to 0.1476±0.0269 %inj/g; p = 0.0014) led to a signifficant increase in insulin uptake in the whole brain. fThe pattern of distribution varied widely between the inhibitors (data not shown). Monensin was the only inhibitor to increase uptake of insulin in all regions of the brain. LY294002 increased insulin uptake in the olfactory bulb, cortex, and remainder, but not in the cerebellum. Phenylarsine oxide increased insulin uptake in the olfactory bulb and cortex. Histamine increased insulin uptake in the cerebellum and remainder. Filipin increased insulin uptake in the cortex and remainder. Verapamil and PMA increased insulin uptake only in the remainder. Lidocaine did not have an effect on any region of the brain. All of the inhibitors used in this study showed a significant increase of 125I-insulin in the serum.

Fig. 4.

Cellular mechanisms of uptake of intranasally administered insulin. The influence of a variety of inhibitors on the percent of 125I-insulin taken up per gram of tissue (%Inj/g) by the olfactory bulb and whole brain (A+B) and per milliliter of serum (%Inj/ml) (C+D) was measured. Inhibitors were administered 30 min prior to intranasal administration of 125I-insulin and brains were harvested 15 min post 125I-insulin administration. Inhibitors are grouped by solubility. Filipin, LY294002, phenylarsine oxide, and PMA are soluble in DMSO (control;A+C). Histamine, verapamil, lidocaine, and monensin are soluble in methanol (control;B+D). Values are expressed as averages SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and #p < 0.001. Data represents an n = 10.

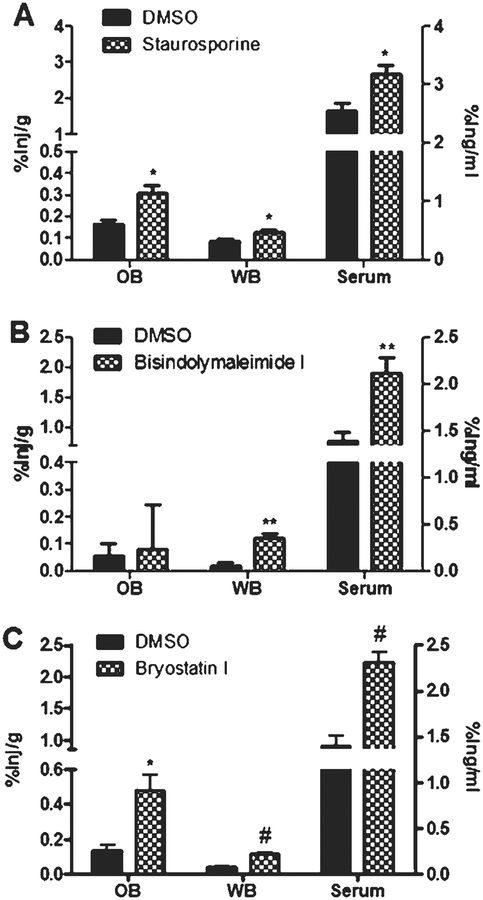

Intranasal treatment with the PKC inhibitors staurosporine, bisindolymaleimide I, and bryostatin I also showed increased uptake in the olfactory bulb, whole brain, and serum (Fig. 5). These inhibitors were administered 30 min prior to intranasal administration of 125Iinsulin. Significant increases in the olfactory bulb were observed for bryostatin I (0.1367±0.03015 %inj/g to 0.4806±0.091 %inj/g; p = 0.0185) and staurosporine 0.166±0.018 %inj/g to 0.3065±0.038 %inj/g; p = 0.0268). Treatment with the PKC inhibitors bryostatin I (0.0352±0.0074 %inj/g to 0.1138±0.0097 %inj/g; p = 0.0001), staurosporine (0.0865±0.0103 %inj/g to 0.1285±0.011 %inj/g; p = 0.0368), and bisindolymaleimide I (0.0924±0.018 %inj/g to 0.151±0.0149 %inj/g; p = 0.0262) showed a significant increase in the uptake of insulin into the whole brain. Furthermore, serum levels were increased after intranasal administration of these PKC inhibitors.

Fig. 5.

PKC inhibition promotes 125I-insulin uptake. CD-1 mice were administered a single intranasal dose of a PKC inhibitor 30 min prior to 125I-insulin being intranasally administered. The percent of 125I-insulin taken up per gram of tissue (%Inj/g) by the olfactory bulb and whole brain and per milliliter of serum (%Inj/ml) was measured for staurosporine (A), bisindolymaleimide I (B), and bryostatin I (C). DMSO was used as a control. Data represents an n = 10. Values are expressed as averages ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and #p < 0.001.

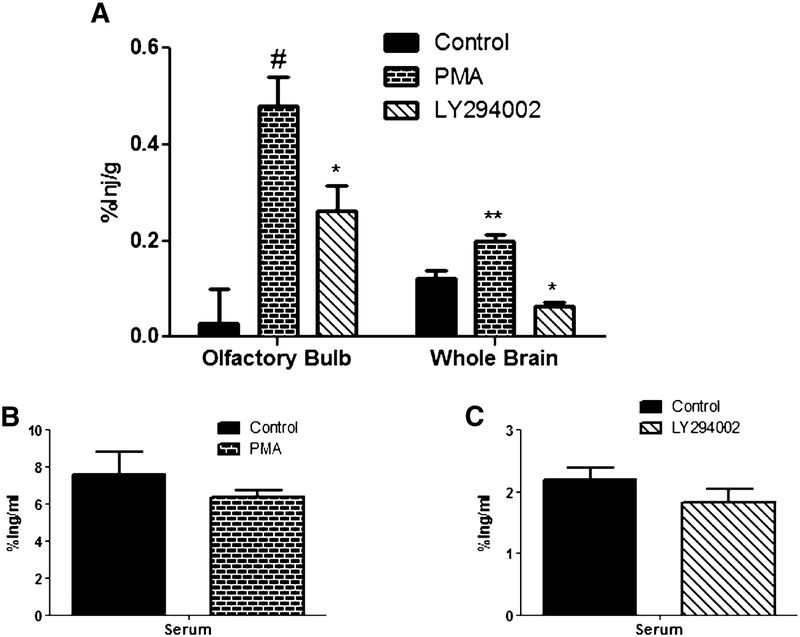

IV injection of 125I-insulin

125I-insulinwas administered intravenously to determine the effects of the inhibitors, PMA and LY294002, on the transport of insulin across the blood-brain barrier (BBB). These inhibitors were administered intranasally 30 min prior to the intravenous injection of 125I-insulin (Fig. 6).PMA showed a significant increase in 125I-insulin uptake in the whole brain (0.122±0.016 to 0.197±0.015; p = 0.0051), while LY294002 showed a significant decrease (0.122±0.016 to 0.063±0.007; p = 0.0152). Both PMA and LY294002 showed no effect on the serum levels. In the olfactory bulb, both PMA (0.027±0.071 to 0.478±0.061; p = 0.0003) and LY294002 (0.027±0.071 to 0.261±0.053; p = 0.0368) showed significant increase in uptake compared to the DMSO control. The serum levels showed no significant differences between the control and inhibitor-treated mice.

Fig. 6.

Transport of 125I-insulin across BBB is unique to that across the nasal epithelial. CD-1 mice were administered a single intrasnasal dose of PMA or LY294002 30 min prior to 125I-insulin being administered intravenously. The percent of 125I-insulin taken up per gram of tissue (%Inj/g) by the olfactory bulb and whole brain (A) and per milliliter of serum (%Inj/ml; PMA (B) and LY294002 (C)) was measured DMSO was used as a control. Data represents an n = 10. Values are expressed as averages ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and #p < 0.001.

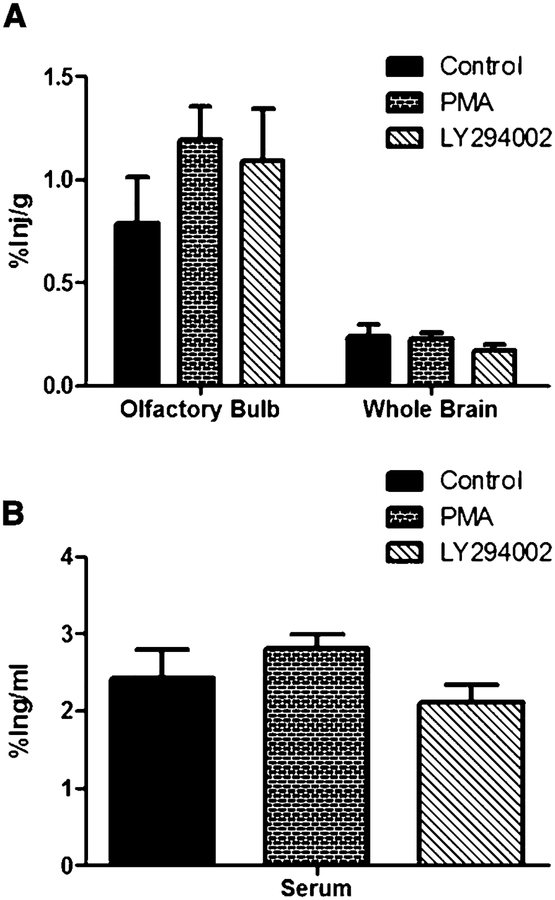

Simultaneous injection of inhibitor and 125I-insulin

To determine whether the increase in 125I-insulin uptake was a direct result of the inhibitor administered, the inhibitor and 125I-insulin were administered simultaneously. LY294002 was chosen since it had the highest amount of 125I-insulin detected in the serum, and PMA, since it had the lowest amount detected in the DMSO control group. Due to issues with the solubility of the 125I-insulin and the inhibitors, a solution could not be made that contained both, thus the inhibitor was administered to the left naris ffirst followed immediately by an administration of 125I-insulin. Administering the inhibitor and the 125I-insulin simultaneously, abolished the effect of the inhibitor on insulin uptake in the brain. Neither serum nor any of the brain regions examined showed signifficant changes compared to the control (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Intranasal co-injection of inhibitors and 125I-insulin abolishes response of the inhibitor. CD-1 mice were administered a single intranasal dose of PMA or LY294002 at the same time as 125I-insulin being administered. The percent of 125I-insulin taken up per gram of tissue (%Inj/g) by the olfactory bulb and whole brain (A) and per milliliter of serum (%Inj/ml; B). DMSO was used as a control. Data represents an n = 10. Values are expressed as averages ± SEM.

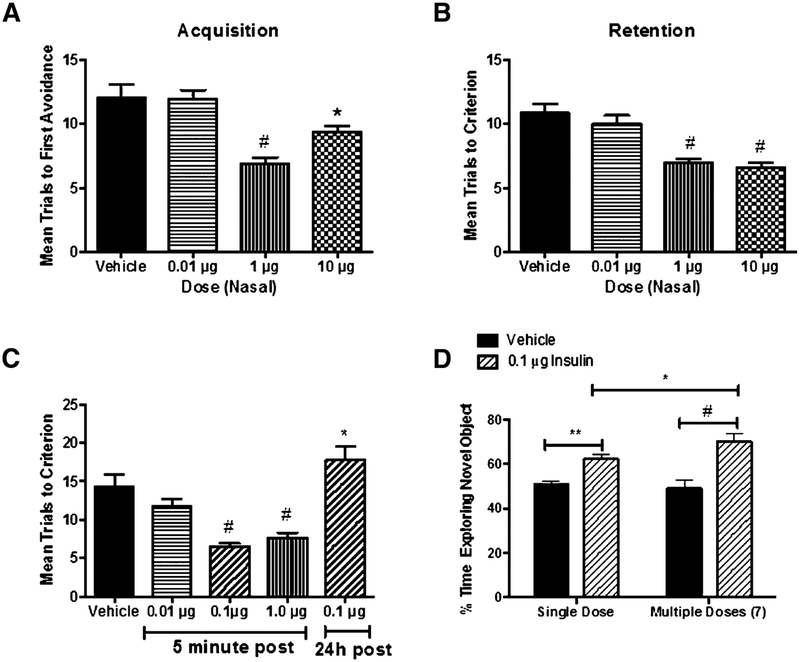

T-maze assessment of cognition

The effect of intranasal insulin on improving cognition was assessed using two different paradigms: administration of insulin 24 h prior to training and administration of insulin post training. Administration of intranasal insulin 24 h prior to training was effective in improving acquisition of the task in SAMP8 mice, a mouse model of AD: F(3,35) = 13.09, p < 0.0001 (Fig. 8A). Neuman-Keuls post-test showed statistical signifficance of the 1 μg/μl (p < 0.0001) and 10 μg/μl (p < 0.05) compared to the vehicle control. The 0.01 μg/μl dose showed no response compared to the vehicle control. Administration of intranasal insulin 24 h prior to training was effective in improving retention, measured 7 days post training, of the task in SAMP8 mice: F(3,35) = 15.87, p < 0.0001 (Fig. 8B). Neuman-Keuls post-test showed statistical signifficance of the 1 μg/μl (p < 0.0001) and 10 μg/μl (p < 0.0001) compared to the vehicle control. The 0.01 μg/μl dose showed no response compared to the vehicle control. However, 1 μg/μl did not improve either acquisition or retention when administered 7 days prior to training (data not shown). Administration of intranasal insulin post training was effective in improving retention, measured 7 days post insulin administration, of the task in SAMP8 mice when the insulin was administered 5 min post training: F(4,42) = 15.97, p < 0.0001 (Fig. 8C). Neuman-Keuls post-test showed statistical signifficance of the 0.1 μg/μl (p < 0.001) and 1 μg/μl (p < 0.0001) compared to the vehicle control. The 0.1 μg/μl dose, when administered 24 h post training showed a statistical increase (p < 0.05) compared to the vehicle control of the mean trials to criterion.

Fig. 8.

Effect of intranasal insulin administration on cognition in SAMP8 mice. In the T-maze assessment of cognition, SAMP8 mice receiving intranasal administration of insulin prior to training, at concentrations ≥1 μg/μl showed signifficant improvement in acquisition (A) and retention (B) of the behavior. When SAMP8 mice received intranasal administration of insulin post training (C), they showed signifficant improvement in memory retention, at concentrations ≥0.1μg/μl, when insulin was administered 5 min post training, and a signifficant decline in memory retention when insulin was administered 24 h post training. In the novel object recognition test of cognition (D), a single dose of 0.1 μg/μl intranasal insulin showed signifficant improvement in the behavior which was enhanced with repeated dosing of insulin. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and #p < 0.001.

Object recognition assessment of cognition

To test whether insulin can improve recognition memory in SAMP8 mice, the novel object recognition task was used (Fig. 8D). SAMP8 mice were given an intranasal injection of insulin every 48 h for two weeks for a total of 7 doses. Object recognition testing was completed 48 h after the ffirst intranasal insulin administration and again at the end of the two weeks. Administration of intranasal insulin was effective in improving recognition memory in SAMP8 mice: F(3,42) = 14.77, p < 0.0001. Neuman-Keuls post-test showed statistical signifficance of the 0.1 μg/μl dose of insulin after 48 h (p < 0.01) and two weeks (p < 0.00001) of treatment compared to the vehicle control. Comparison of the testing after a single dose of intranasal insulin administration and two-weeks of insulin administration showed a statistically signifficant (p < 0.05) improvement with the repeated dosing.

DISCUSSION

Clinical research investigating the effects on cognitive memory processes of intranasally administered insulin in patients with AD and MCI has yielded promising results; however, additional clinical trials are needed to further assess the clinical relevance of intranasal insulin in the treatment of cognitive disorders. Interestingly, the clinical studies have identiffied gender and ApoE genotype differences in treatment responses to intranasal insulin [17]. Understanding the mechanism by which insulin is taken up and distributed in the brain after intranasal administration will aid in the enhancement of this therapeutic option to treat all groups of AD patients. In this study, we investigated distribution of 125I-insulin into the brain and serum after intranasal administration. We detected rapid distribution of 125I-insulin in all regions of the brain to some varying degree. The rapid distribution of 125I-insulin is concordant with studies that showed the involvement of the perivascular space of cerebral blood vessels in the distribution of intranasally administered macromolecules [20]. Consistent with studies examining the transport of insulin across the BBB, the highest level of uptake occurred in the olfactory bulbs. This region is known to have the highest concentration of insulin protein [29], the highest concentration of insulin receptors [30], and the highest rate of insulin degradation. When administered intravenously, 125I-insulin does not transport into all regions of the brain in ICR mice and SAMP8 mice [31, 32], however, when administered intranasally it was detected in all regions analyzed. At most, less than 3% of intranasally-delivered 125I-insulin was detected in the serum of the CD-1. This amount was not suffficient to induce a metabolic response in the animals as observed from the CLAMS data and does not result in a hyperinsulinemic state in the mice. Hyperinsulinemia is a condition often associated with hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia, and glucose intolerance, which would negatively impact the effect of the intranasal treatment if it were a side effect of the treatment.

Insulin is transported across the BBB in the blood-to-brain direction through a saturable transport system [33, 34]. We observed a similar saturable transport system at the nasal epithelium. Decreased uptake of 125I-insulin was observed in the olfactory bulb, whole brain, and in the serum. The cerebellum (data not shown) was the only region examined that showed no change in 125I-insulin transport when challenged by the unlabeled insulin. This was surprising given that this is a region that expresses high levels of insulin receptors [35]. To further explore the mechanism by which insulin is transported across the nasal epithelium, an array of inhibitors were used to block various aspects of protein transport. It is known that insulin crosses the BBB, however the mechanism by which this occurs has not been elucidated. As a result, a direct method in which to inhibit this process is unknown. Our array of inhibitors covers a wide variety of basic transport systems; from N-type Ca2+ channels to caveolae-dependent transcytosis. Our goal was to elucidate the mechanism by which insulin was transported across the nasal epithelium through the inhibition of different pathways. Interestingly, instead of preventing insulin uptake into the brain, the majority of the inhibitors tested showed an increase in 125I-insulin uptake. These included agents such as phenylarsine oxide, which has effects on N-type Ca2+ channel currents and phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase, an important component of the 4,5-biphosphate signal pathway that blocks receptor-mediated transcytosis. Phenylarsine oxide has also been shown to inhibit insulin-stimulated glucose transport without affecting insulin binding and tyrosine kinase activity of the insulin receptor, and it is capable of promoting insulin secretion from INS-1 cells in the presence of insulin or IGF-1, factors known to inhibit insulin release [36]. Verapamil, the L- and T-type Ca2+ channel blocker, which also inhibits P-glycoprotein, the ATP-dependent drug transport protein, also increased 125I-insulin uptake. Filipin, a cholesterol-binding agent that inhibits caveolae-dependent transcytosis, increased 125I-insulin uptake. Interestingly, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor, LY294002, known to inhibit insulin signaling, also increased uptake of 125I-insulin. Monensin, a compound that inhibits acidiffication of intracellular organelles to prevent endocytosis and delivery of macromolecules to lysosomes was able to increase uptake of 125I-insulin into the brain. Lastly, histamine, a vasogenic agent, which increases BBB permeability also increased 125I-insulin uptake into the brain. None of the active inhibitors had effects when given immediately with insulin, ruling out steric or other types of non-metabolic interactions. The only inhibitors that had no effect on 125I-insulin uptake were PMA, the PKC activator known to stimulate fluid phase transcytosis, and lidocaine, which acts to block the conduction of action potentials by closing voltage dependent Na+ channels. A literature search was conducted to identify a commonality between the inhibitors that displayed increased 125I-insulin uptake into the brain. Results of this search indicated that these inhibitors were all involved in the inhibition of PKC activity. Those inhibitors that had no effect on 125I-insulin uptake, lidocaine and PMA, are known activators of PKC. To verify this ffinding, known PKC inhibitors, staurosporine, bisindolymaleimide I, and bryostatin I, were used to examine 125I-insulin uptake into the brain. These PKC inhibitors also demonstrated an increased uptake of 125I-insulin into the brain. This observation is contradictory to what is observed in muscle where PKC activation leads to increased uptake. The effects observed here are unique to insulin since studies completed with these inhibitors and 125I-albumin have shown a completely different proffile in regards to uptake into the brain post intranasal administration [37].

Insulin in the periphery is known to cross the BBB [34]. Comparison of intranasally administered 125I-insulin and intravenously administered 125I-insulin following an intranasal administration of the inhibitors, LY294002 and PMA, showed a major contrast. This implies that the transport mechanism of 125I-insulin across the BBB differs from that of the nasal epithelium.

To determine whether enough insulin can enter the brain after intranasal administration suffficient to exert effects on CNS function, we used the SAMP8 mice, an animal model of AD. The SAMP8 strain of mice has a natural mutation where, as it ages, it develops defects in both learning and memory, cholinergic defficits, oxidative stress in brain, decreased reabsorption of cerebrospinal fluid, impaired brain-to-blood efflux of amyloid-β protein, and elevated levels of amyloid-β protein [38–42]. At young ages, these mice show a phenotype similar to wildtype counterparts. Results from our T-maze assessment of memory showed that a single dose of intranasal insulin administered 24 h prior to training, but not when administered 7 days prior to training, was able to affect both acquisition and retention of the task. This shows that a single dose of insulin could improve cognition for at least 24 h but not more than 7 days. Administration of insulin when given 5 min post training, but not when given 24 h post training, showed a positive effect on memory; this suggests that in this case insulin was likely affecting memory consolidation. This demonstrates the importance of the insulin being present at the time of memory acquisition in order for consolidation to occur. Novel object recognition, an alternative test of cognition, also demonstrated a positive effect of post intranasal insulin administration. Here we were able to show that chronic administration of insulin did not extinguish the effect, but had a more profound effect in comparison to a single administration of intranasal insulin. Insulin is not the only compound to have benefficial effects on cognition with intranasal administration. Oxytocin, exendin, and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide have also shown improvements on cognition after intranasal administration [23, 43, 44].

Intranasal insulin delivery has been successful in the treatment of patients with AD. This study provides evidence for the mechanism of uptake of intranasally-administered insulin and has provided evidence that it is effficacious in improving cognition in animal models of AD. The results presented here provide framework for enhancing intranasal administration so that it could potentially treat increased number of patients with AD, including females and APOE ε4 positive individuals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Aging (Grant R01-AG046619). Therese S. Salameh is supported by National Institutes of Health National Institute on Aging (Grant T32-AG000258). We would like to acknowledge the Rodent Metabolic and Behavioral Phenotyping Core at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/15-0307r1).

REFERENCES

- [1].Hölscher C, Li L (2010) New roles for insulin-like hormones in neuronal signalling and protection: New hopes for novel treatments of Alzheimer’s disease? Neurobiol Aging 31, 1495–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].de la Monte SM, Tong M (2014) Brain metabolic dysfunction at the core of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Pharmacol 88, 548–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rivera EJ, Goldin A, Fulmer N, Tavares R, Wands JR, de la Monte SM (2005) Insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and function deteriorate with progression of Alzheimer’s disease: Link to brain reductions in acetylcholine. J Alzheimers Dis 8, 247–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Talbot K, Wang H-Y, Kazi H, Han L-Y, Bakshi KP, Stucky A, Fuino RL, Kawaguchi KR, Samoyedny AJ, Wilson RS, Arvanitakis Z, Schneider JA, Wolf BA, Bennett DA, Trojanowski JQ, Arnold SE (2012) Demonstrated brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease patients is associated with IGF-1 resistance, IRS-1 dysregulation, and cognitive decline. J Clin Invest 122, 1316–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Steen E, Terry BM, Rivera EJ, Cannon JL, Neely TR, Tavares R, Xu XJ, Wands JR, de la Monte SM (2005) Impaired insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and signaling mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease - is this type 3 diabetes? J Alzheimers Dis 7, 63–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Plum L, Schubert M, Brüning JC (2005) The role of insulin receptor signaling in the brain. Trends Endocrinol Metab 16, 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Abbott M-A, Wells DG, Fallon JR (1999) The insulin receptor tyrosine kinase substrate p58/53 and the insulin receptor are components of CNS synapses. J Neurosci 19, 7300–7308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].McNay EC, Ong CT, McCrimmon RJ, Cresswell J, Bogan JS, Sherwin RS (2010) Hippocampal memory processes are modulated by insulin and high-fat-induced insulin resistance. Neurobiol Learn Mem 93, 546–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Benedict C, Hallschmid M, Hatke A, Schultes B, Fehm HL, Born J, Kern W (2004) Intranasal insulin improves memory in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29, 1326–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kern W, Peters A, Fruehwald-Schultes B, Deininger E, Born J, Fehm HL (2001) Improving influence of insulin on cognitive functions in humans. Neuroendocrinology 74, 270–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chen Y, Run X, Liang Z, Zhao Y, Dai C-l, Iqbal K, Liu F, Gong C-X (2014) Intranasal insulin prevents anesthesia-induced hyperphosphorylation of tau in 3xTg-AD mice. Front Aging Neurosci 6, 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dong Y, Wu X, Xu Z, Zhang Y, Xie Z (2012) Anesthetic isoflurane increases phosphorylated tau levels mediated by caspase activation and Aβ generation. PLoS OneE 7, e39386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shen X, Dong Y, Xu Z, Wang H, Miao C, Soriano SG, Sun D, Baxter MG, Zhang Y, Xie Z (2013) Selective anesthesia-induced neuroinflammation in developing mouse brain and cognitive impairment. Anesthesiology 118, 502–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bianchi SL, Tran T, Liu C, Lin S, Li Y, Keller JM, Eckenhoff RG, Eckenhoff MF (2008) Brain and behavior changes in 12-month-old Tg2576 and nontransgenic mice exposed to anesthetics. Neurobiol Aging 29, 1002–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Craft S, Baker LD, Montine TJ, Minoshima S, Watson GS, Claxton A, Arbuckle M, Callaghan M, Tsai E, Plymate SR, Green PS, Leverenz J, Cross D, Gerton B (2012) Intranasal insulin therapy for Alzheimer disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment: A pilot clinical trial. Arch Neurol 69, 29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Reger MA, Watson GS, Frey Ii WH, Baker LD, Cholerton B, Keeling ML, Belongia DA, Fishel MA, Plymate SR, Schellenberg GD, Cherrier MM, Craft S (2006) Effects of intranasal insulin on cognition in memory-impaired older adults: Modulation by APOE genotype. Neurobiol Aging 27, 451–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Claxton A, Baker LD, Wilkinson CW, Trittschuh EH, Chapman D, Watson GS, Cholerton B, Plymate SR, Arbuckle M, Craft S (2013) Sex and ApoE genotype differences in treatment response to two doses of intranasal insulin in adults with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 35, 789–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rosenbloom M, Barclay T, Pyle M, Owens B, Cagan A, Anderson C, Frey W II, Hanson L (2014) A single-dose pilot trial of intranasal rapid-acting insulin in apolipoprotein E4 carriers with mild–moderate Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drugs 28, 1185–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lochhead JJ, Thorne RG (2012) Intranasal delivery of biologics to the central nervous system. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 64, 614–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lochhead JJ, Wolak DJ, Pizzo ME, Thorne RG (2015) Rapid transport within cerebral perivascular spaces underlies widespread tracer distribution in the brain after intranasal administration. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 35, 371–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Greenwood FC, Hunter WM (1963) The preparation of 131I-labelled human growth hormone of high speciffic radioactivity. Biochem J 89, 114–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Glowinski J, Iversen L (1966) Regional studies of catecholamines in the rat brain. I. The disposition of[3H]norepinephrine, [3H]dopamine and [3H]dopa in various regions of the brain. J Neurochem 13, 655–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Nonaka N, Farr SA, Nakamachi T, Morley JE, Nakamura M, Shioda S, Banks WA (2012) Intranasal administration of PACAP: Uptake by brain and regional brain targeting with cyclodextrins. Peptides 36, 168–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fiorini A, Sultana R, Förster S, Perluigi M, Cenini G, Cini C, Cai J, Klein JB, Farr SA, Niehoff ML, Morley JE, Kumar VB, Allan Butterffield D (2013) Antisense directed against PS-1 gene decreases brain oxidative markers in aged senescence accelerated mice (SAMP8) and reverses learning and memory impairment: A proteomics study. Free Radic Biol Med 65, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hammond RS, Tull LE, Stackman RW (2004) On the delay-dependent involvement of the hippocampus in object recognition memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem 82, 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Farr SA, Erickson MA, Niehoff ML, Banks WA, Morley JE (2014) Central and peripheral administration of anti-sense oligonucleotide targeting amyloid precursor protein improves learning and memory and reduces neuroinflamma-tory cytokines in Tg2576 (APPswe) mice. J Alzheimers Dis 40, 1005–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Farr SA, Ripley JL, Sultana R, Zhang Z, Niehoff ML, Platt TL, Murphy MP, Morley JE, Kumar V, Butterffield DA (2014) Antisense oligonucleotide against GSK-3β in brain of SAMP8 mice improves learning and memory and decreases oxidative stress: Involvement of transcription factor Nrf2 and implications for Alzheimer disease. Free Radic Biol Med 67, 387–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Quinn LS, Anderson BG, Conner JD, Wolden-Hanson T (2012) IL-15 overexpression promotes endurance, oxidative energy metabolism, and muscle PPARδ, SIRT1, PGC-1α, and PGC-1β expression in male mice. Endocrinology 154, 232–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Baskin DG, Porte D, Guest K, Dorsa DM (1983) Regional concentrations of insulin in the rat brain. Endocrinology 112, 898–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hill JM, Lesniak MA, Pert CB, Roth J (1986) Autoradiographic localization of insulin receptors in rat brain: Prominence in olfactory and limbic areas. Neuroscience 17, 1127–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Banks WA, Farr SA, Morley JE (2000) Permeability of the blood-brain barrier to albumin and insulin in the young and aged SAMP8 mouse. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 55, B601–B606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Banks WA, Kastin AJ (1998) Differential permeability of the blood–brain barrier to two pancreatic peptides: Insulin and amylin. Peptides 19, 883–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Baura GD, Foster DM, Porte D Jr., Kahn SE, Bergman RN, Cobelli C, Schwartz MW (1993) Saturable transport of insulin from plasma into the central nervous system of dogs in vivo. A mechanism for regulated insulin delivery to the brain. J Clin Invest 92, 1824–1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Banks WA, Jaspan JB, Huang W, Kastin AJ (1997) Transport of insulin across the blood-brain barrier: Saturability at euglycemic doses of insulin. Peptides 18, 1423–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hopkins DFC, Williams G (1997) Insulin receptors are widely distributed in human brain and bind human and porcine insulin with equal afffinity. Diabetic Med 14, 1044–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Verspohl EJ (2006) Effect of PAO (phenylarsine oxide) on the inhibitory effect of insulin and IGF-1 on insulin release from INS-1 cells. Endocrine J 53, 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Falcone JA, Salameh TS, Yi X, Cordy BJ, Mortell WG, Kabanov AV, Banks WA (2014) Intranasal administration as a route for drug delivery to the brain: Evidence for a unique pathway for albumin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 351, 54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Banks WA, Farr SA, Morley JE, Wolf KM, Geylis V, Steinitz M (2007) Anti-amyloid beta protein antibody passage across the blood–brain barrier in the SAMP8 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: An age-related selective uptake with reversal of learning impairment. Exp Neurol 206, 248–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Farr SA, Poon HF, Dogrukol-Ak D, Drake J, Banks WA, Eyerman E, Butterffield DA, Morley JE (2003) The antioxidants α-lipoic acid and N-acetylcysteine reverse memory impairment and brain oxidative stress in aged SAMP8 mice. J Neurochem 84, 1173–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Poon HF, Joshi G, Sultana R, Farr SA, Banks WA, Morley JE, Calabrese V, Butterffield DA (2004) Antisense directed at the Aβ region of APP decreases brain oxidative markers in aged senescence accelerated mice. Brain Res 1018, 86–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Morley JE, Armbrecht HJ, Farr SA, Kumar VB (2012) The senescence accelerated mouse (SAMP8) as a model for oxidative stress and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1822, 650–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Erickson MA, Niehoff ML, Farr SA, Morley JE, Dillman LA, Lynch KM, Banks WA (2012) Peripheral administration of antisense oligonucleotides targeting the amyloid-β protein precursor reverses AβPP and LRP-1 overexpression in the aged SAMP8 mouse brain. J Alzheimers Dis 28, 951–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Davis MC, Lee J, Horan WP, Clarke AD, McGee MR, Green MF, Marder SR (2013) Effects of single dose intranasal oxytocin on social cognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 147, 393–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].During MJ, Cao L, Zuzga DS, Francis JS, Fitzsimons HL, Jiao X, Bland RJ, Klugmann M, Banks WA, Drucker DJ, Haile CN (2003) Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor is involved in learning and neuroprotection. Nat Med 9, 1173–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]