Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

The objective of this study was to assess the knowledge, perception, and professional experience of pediatricians in Saudi Arabia regarding child abuse and neglect.

DESIGN AND SETTING

Descriptive study during a one day pediatric conference held on King King Abdulaziz University Hospital, a tertiary care teaching hospital in western Saudi Arabia.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The study targeted 198 attendees who were invited from different healthcare sectors in the country.

RESULTS

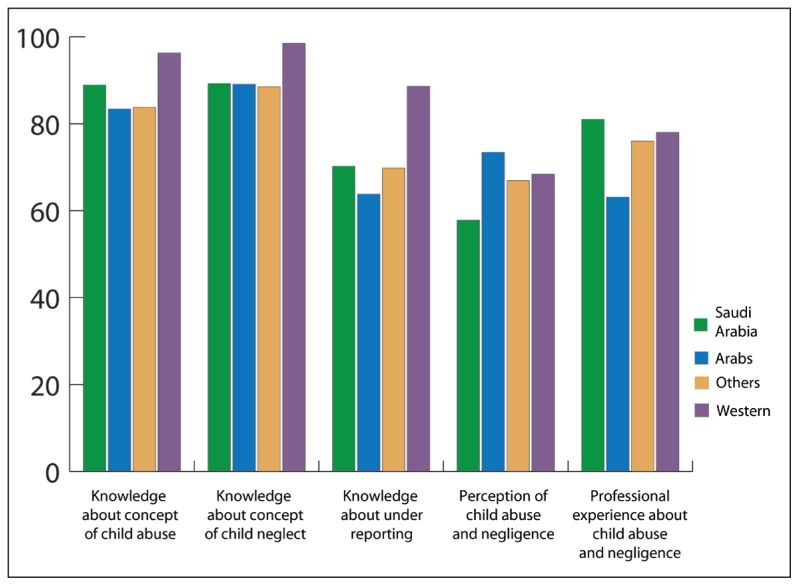

The overall knowledge of participants about some important aspects of child abuse and negligence was adequate, ranging between 82% and 91%. However, their knowledge about reporting cases of child abuse and neglect was quite deficient, ranging between 66% and 79%. As for “professional experience about child abuse and negligence,” it showed considerable variation between participants ranging between 43% and 82%, in which pediatricians who received their medical education in Saudi Arabia scored statistically significantly higher, while pediatricians who received their medical education in Western countries scored higher in all other aspects of the study.

CONCLUSIONS

Currently, the knowledge and clinical experience on the subject of child abuse and neglect in Saudi Arabia is enough to adopt a comprehensive strategy for the prevention and interventions of child maltreatment at all levels. Pediatricians are expected to play a key role by leading and facilitating this process.

Child maltreatment encompasses a spectrum of both abusive actions—”acts of commission”— and lack of actions—”acts of omission”—that result in morbidity or death of the child.1 Over the centuries, children have been killed, maimed, starved, abandoned, and neglected. However, the issue of child maltreatment did not come to the forefront of medical attention worldwide until the past two decades.2,3

In the Arab world, child maltreatment is an issue that is rarely exposed or studied. In Saudi Arabia, 13 cases of child abuse and neglect were reported in the emergency room of King Khalid University Hospital over a period of 1 year from July 1997 to June 1998.4

Until the 1990s, cases of child abuse and neglect went unpublished by medical professionals in Saudi Arabia. Indeed, some physicians resist diagnosing child abuse or neglect because of inadequate training, the problem of establishing the diagnosis with certainty, the risk of stigmatizing the family, personal and legal risks, and the potential effect on their practice. Others are reluctant to become involved in social or legal bureaucracy. 5

A study was conducted by Al-Mahroos to provide an overview of the problem and patterns of child abuse and neglect in the seven countries of the Arab Peninsula depending on the revision of medical reports, published between January 1987 and May 2005.6 In addition, reports were obtained from regional meetings and professional organizations. It was concluded that children in the Arab Peninsula are subjected to all forms of child abuse and neglect. Child abuse is ignored or may even be tolerated and accepted as a form of discipline; abused children continue to suffer and most abusers go free, unpunished, and untreated.6

Saudi Arabia signed and ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, and toward the end of the decade child abuse and neglect (CAN) was already recognized at major health facilities throughout the country. While hospitals continued to receive increased CAN cases, the magnitude of the problem in Saudi Arabia, even in these settings, was not known because of the lack of accurate statistics on incidence and prevalence. One consequence of the lack of information was that risk factors, indicators, categories, definitions, and the nature of the problem of child maltreatment were not well identified and therefore, multidisciplinary services for the victims of abuse and their families were not well informed and developed in the country.7 When physical disciplining actually occurred, the resulting potential abuse and/or neglect remained within the confirmed sanctity of family privacy. Most critical social and behavioral problems were dealt with under the good counsel of elderly members of the family.8 These norms of discretion have prevailed over centuries in the Arab world and have meant that social issues such as children’s maltreatment or domestic violence are discussed very reluctantly.9

Abused or neglected children may suffer serious negative impacts and consequences. Worldwide studies of abused children returned to their parents without any intervention indicate that about 5% are subsequently killed and that 25% are seriously reinjured. However, with comprehensive, intensive family treatment, 80% to 90% of families involved in child maltreatment may be rehabilitated to provide adequate care for their children. 10

Among physical and mental health professionals, pediatricians are considered the key to the discovery of abuse and/or neglect, as well as the measurement of the seriousness of the abusive act, in particular during the infancy period when pediatricians have an important role in the early screening and detection of children at high risk of abuse and/or neglect.11 As our understanding of child maltreatment continues to grow, evidence-based interventions are adopted by hospital-based child protection teams enabling them to standardize their care. This will likely be in the sake of abused children and their families as a priority for their society.12 However, pediatricians in developing countries may face other challenges such as medical neglect of children with potentially fatal health problems, and the characteristics of the child, family, and cultural fatalistic beliefs.13 Therefore, this cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the knowledge, perception, and professional experience of pediatricians in Saudi Arabia regarding child abuse and/or neglect, two problems that have been barely studied in the Arab communities as a whole.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study was preceded by a pilot study with 20 doctors at the Paediatric Department, Faculty of Medicine, King Abdel-Aziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Necessary revisions, modifications, and corrections of some questions were done on assessment of the results. This study was conducted to assess the knowledge, perceptions, and professional experience of pediatricians in Saudi Arabia regarding child abuse and/or neglect, two problems that are hardly explored in Arab countries. This took place during April 2007 and targeted 198 attendees of a “pediatric conference” held in the Faculty of Medicine, King Abdel-Aziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The questionnaire consisted of five parts, namely, demographic data, concept, perception, professional experience, and reporting in Saudi Arabia and the exploration of some situations representing forms of child abuse and/or neglect. It consisted of a Likert scale with responses ranked 1 to 5 as follows: 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (not known), 4 (agree), and 5 (strongly agree)

The statistical analysis was done by using the PC “Statsoft” statistical package “Statistica” v. 8.0 Statsoft, Oklahoma, United States (http://www.statsoft.com) (2007). Data were presented in the form of numbers and percentages in response to questions. The z test for testing the significance of difference between percentages and the t test for testing the significance of difference between two sample arithmetic means were used. A statistical difference was considered significant at P<.05.

RESULTS

This study was conducted at a “pediatric conference” held in the Faculty of Medicine, King Abdel-Aziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, in which a questionnaire was distributed to 198 attendees. The response rate was 142/198 (71.7%, P<.001), of all attendees whose ages ranged from 24 to 58 years (mean 34.6 years). Female attendees represented 56.3% Their work experience ranged from 2 to 30 years, (mean 7.4 years). Table 1 shows the demographics of the participant pediatricians and their postgraduate training concerning child maltreatment.

Table 1.

Personal and professional characters of the participating pediatricians (n=142).

| Variables | Number | (%) | z test | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 62 | 43.7 | 1.523 | NS |

| Female | 80 | 56.3 | ||

|

| ||||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 94 | 66.2 | 4.080 | <.001 |

| Unmarried | 48 | 33.8 | ||

|

| ||||

| Work position at the hospital | ||||

| Consultant | 29 | 20.4 | 1 vs 2 | <.001 |

| 2.921 | ||||

| Specialist | 55 | 38.7 | 1 vs 3 | <.001 |

| 3.221 | ||||

| Resident | 58 | 40.8 | 2 vs 3 | NS |

| 0.282 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Specialization | ||||

| Pediatric (medical) | 134 | 94.4 | 22.929 | <.001 |

| Pediatric (surgical) | 8 | 5.6 | ||

|

| ||||

| Country of medical education | ||||

| Saudi Arabia | 65 | 45.8 | 1 vs 2 | <.05 |

| 2.151 | ||||

| Other Arab countries | 43 | 30.3 | 1 vs 3 | <.001 |

| 7.007 | ||||

| Western countries | 12 | 8.5 | 1 vs 4 | <.001 |

| 4.999 | ||||

| Pakistan or India | 22 | 15.5 | 2 vs 3 | <.001 |

| 4.464 | ||||

| 2 vs 4 | <.005 | |||

| 2.669 | ||||

| 3 vs 4 | <.05 | |||

| 1.733 | ||||

NS: Nonsignificant.

The overall knowledge of participants about some important aspects of child abuse and negligence is presented in Table 2. Knowledge ranging between 82.0% to 92.0% and 86.2% to 91.4% was considered to be adequate, whereas less than 79% was considered deficient knowledge. Their knowledge about reporting cases of CAN was relatively deficient, ranging between 57.0% and 79.4% with a statistically nonsignificant difference between the highest/lowest responses. Also, their perception, and professional experience regarding CAN were not optimal, ranging between 51.4% and 86.0% with a mean (SD) of 69.8% (16.8%) between the highest and lowest responses in favor of “I prefer to redefine child abuse and negligence” over “I prefer to resolve the case rather than reporting.” The perception of the problem of the magnitude of CAN varied considerably, between participants ranging between 43.2% and 82.2% with a mean (SD) of 70.1% (13.6%) between highest and lowest responses in favor of “Supportive services are inadequate” over “Child maltreatment is a rare problem.”

Table 2.

Knowledge, perception, and professional experience of pediatricians regarding child abuse and neglect.

| Percent | z test highest/lowest | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Knowledge about child abuse | 0.977 P=NS |

|

| Burning child for misbehavior | 90.4 | |

| Locking a child alone at home for long hours | 90.0 | |

| Beating the child severely leaving body marks | 92.8↑ | |

| Throwing different objects on the child | 84.8 | |

| Smoking at home in the presence of children | 82.0↓ | |

| Mean percent (SD) | 88.0 (4.4) | |

|

| ||

| Knowledge about child neglect | 0.465 P=NS |

|

| Parents refusing sending the child to school | 90.4 | |

| Parents refusing assistance of medical/surgical health team to the child | 90.8 | |

| No attention to the child cleanliness | 86.2↓ | |

| Child fails to thrive because of social deprivation | 87.4 | |

| Parents refusing dental care of children | 91.4↑ | |

| Mean percent (SD) | 89.2 (2.3) | |

|

| ||

| Knowledge about reporting | 0.465 P=NS |

|

| It is not legally mandating to report | 65.8 | |

| Report is not good for the sake of the child | 57.0 ↓ | |

| Reporting procedures are unclear | 79.4 ↑ | |

| Reporting to authorities is not accepted | 68.8 | |

| Fear of parent response | 74.0 | |

| Mean percent (SD) | 69.0 (8.5) | |

|

| ||

| Perception of child abuse and neglect | 3.618 P<.001 |

|

| I prefer to redefine child abuse and negligence | 86.0↑ | |

| I prefer to resolve the case rather than reporting | 51.4↓ | |

| I prefer to report all cases | 52.0 | |

| I am aware of reporting sites in Saudi Arabia | 77.8 | |

| I prefer reporting of only lifethreatening conditions | 82.0 | |

| Mean percent (SD) | 69.8 (16.8) | |

|

| ||

| Professional experience about child abuse and neglect | 4.427 P<.001 |

|

| Child maltreatment is under recognized | 82.0 | |

| Child maltreatment is a rare problem | 43.2↓ | |

| The trend of it is increasing | 74.0 | |

| The community awareness increased | 67.0 | |

| Professional awareness increased | 64.8 | |

| Supportive services are inadequate | 82.2↑ | |

| Child abuse and neglect are not reported | 77.4 | |

| Mean percent (SD) | 70.1 (13.6) | |

NS: Nonsignificant; SD: standard deviation. Arrows indicate higher and lowest values. P<.05 indicates statistically significant difference between highest and lowest values.

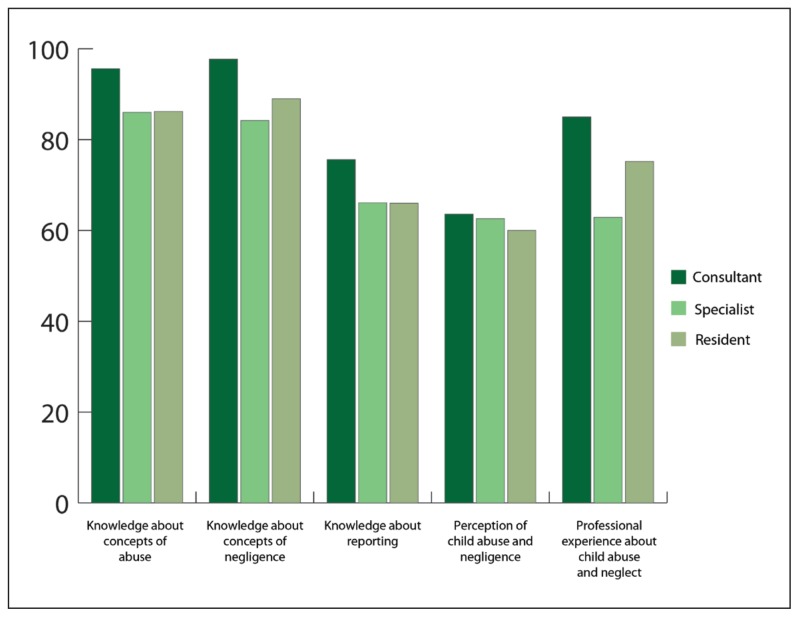

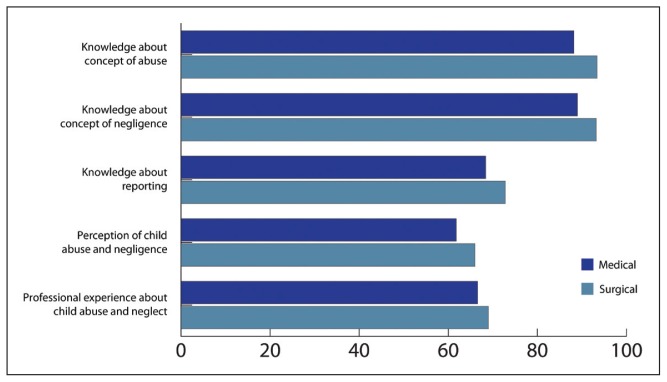

Regarding the scientific levels and/or work position of participating pediatricians, consultants scored statistically significantly higher in most aspects of CAN over residents or specialists. However, statistically nonsignificant differences were found concerning “Knowledge about reporting” and “Perception of child abuse and negligence” (Figure 1). The overall knowledge of all groups regarding reporting is poor and needs more clarification. However, pediatric surgeons scored statistically nonsignificantly higher in all aspects of the study of CAN over other participating pediatricians (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Knowledge, perception, and professional experience of the studied pediatricians about the concept of child abuse and negligence according to their scientific levels or work position.

Figure 2.

Knowledge, perception, and professional experience of the studied pediatricians about child abuse and negligence according to specialties.

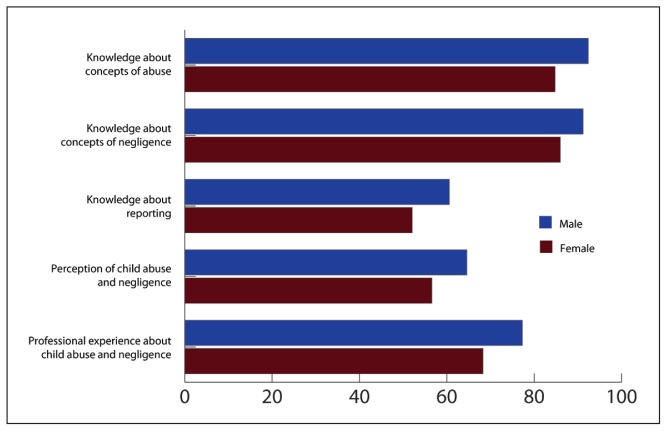

As for “professional experience about child abuse and negligence,” pediatricians who received their medical education in Saudi Arabia scored statistically significantly higher (P<.005), while pediatricians who received their medical education in Western countries scored higher (P<.05, P<.001) in all other aspects of the study (Figure 3). Female pediatricians scored a statistically nonsignificant difference compared with male pediatricians on the knowledge of CAN, yet both showed deficient knowledge on the reporting strategy and reporting methodology (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Knowledge, perception, and professional experience of the studied pediatricians about child abuse and negligence according to the country of medical education.

Figure 4.

Knowledge, perception, and professional experience of the studied pediatricians about child abuse and negligence according to gender.

DISCUSSION

Child maltreatment including physical abuse and neglect is reported in all countries and cultures. Child maltreatment usually results from interactions between several risk factors (such as parental depression, stress, and social isolation and others).14 Suspected cases of child abuse should be well documented and reported to the appropriate public agency that should assess the situation and help to protect children.14 Accurate and timely diagnosis of children who are suspected victims of abuse can ensure appropriate evaluation, investigation, and outcomes for these children and their families. 15

Although a challenge in all countries, CAN may be underestimated and underreported in some countries, especially the developing ones. Results from a study in the eastern cities of Turkey indicate that primary care physicians do not have adequate knowledge and well-developed attitudes toward the identification and reporting of suspected child abuse.16 In Saudi Arabia, child maltreatment is currently an issue that has become further discussed in the media. Therefore, this study was conducted to evaluate the knowledge, perception, and professional experience of pediatricians in Saudi Arabia regarding CAN, a problem that may be rarely studied in the Arab communities as a whole.

This cross-sectional survey study showed that although the knowledge of participants about some important aspects of CAN was adequate, their knowledge about reporting cases of CAN was relatively deficient. Also, their perception and professional experience regarding CAN were not optimal. These data may reflect to some extent the serious problem of underreporting of cases of child maltreatment in Saudi Arabia or other Arab countries. This can lead to underestimation of the magnitude of the problem of CAN and consequently interfere with the development of interventions to manage this problem.

No controversy was seen regarding the professional experience of the participants, as the majority agreed that child maltreatment is underrecognized, while the minority thought that child maltreatment is a rare problem. Again, this may be explained by deficient reporting, which is a serious problem in Arab countries.

In this study, consultants had significantly higher knowledge, perception, and more professional experience in almost all aspects of CAN than do residents or specialists (Figure 1). This was particularly evident regarding the concepts of child neglect. Although child neglect is the most common form of child maltreatment, pediatric residents and specialists may be unaware of some concepts of child neglect, and they need more education and training about the variable aspects of child neglect including medical neglect.

In addition, this study showed that pediatric surgeons and pediatricians had incomplete knowledge about reporting cases of child maltreatment. Although surgeons do not have much contact with cases of CAN except if there are severe physical injuries. Surprisingly, in the case of professional experience about child abuse and/or neglect, pediatricians who received their medical education in Saudi Arabia scored statistically significantly the highest (showed greater knowledge). Acquaintance with the native society could be the main reason.

Worldwide, the decision to report cases of CAN is influenced by many factors including inadequate training to diagnose the problem, the risk of stigmatizing the family, the desire to manage the case oneself, and the lack of confidence in child protective services.12 In addition, it is possible to observe differences with respect to pediatricians’ willingness to report various types of abuse and neglect. For example, the willingness to report situations of educational neglect and psychological abuse was lower than for other categories, both in reporting to the welfare department and in reporting to the police.11 Many physicians have reported child abuse to social services and also have neglected to do so even when suspecting sexual abuse. It is important that medical students’ willingness to report is continued when starting to work clinically and that all physicians should be continuously educated.17

As in our study, Al-Moosa et al18 in Kuwait found that more than 80% of pediatricians in public hospitals did not know whether there was a legal obligation to report or which legal authorities should receive reports of suspected cases of child maltreatment. Physicians treating possible victims can report the case to the department of social services available in each of the five health regions of the country. However, there is no obligation on the family to accept the services proposed by social workers. Also, the majority of physicians in Kuwait are expatriates, most coming from less advantaged Arab or Asian countries; those physicians may be reluctant to face the hostility of local families should they attempt to report suspected cases of maltreatment.18

Therefore, the cornerstone in dealing with the problem of child maltreatment in Saudi Arabia or other Arab countries seems to be directed toward construction of a legal framework concerned with reporting suspected cases of child maltreatment and protecting reporting physicians. Of course laws will be affected by cultural and social habits prevailing in a certain community, but specific serious patterns of child maltreatment should be reported. Also, standardized procedures of reporting should be known to reporters. This should lead to increased awareness in the Arab communities about child maltreatment, understanding the value of reporting to prevent future child morbidity or mortality, and institution of active measures to manage and prevent this important problem. Furthermore, continuous education and training of all physicians, social workers, and teachers to increase their knowledge about the epidemiology, patterns, and risk factors for CAN as well as improving their skills in detection, assessment, reporting, treatment, and prevention of CAN is essential. This is particularly important for pediatricians who did not receive their medical education in Western countries.

As pediatricians are the professionals who have frequent contact with families, they have the opportunity to assess family interactions and relationships. They should initiate recognition of the problem and its risk factors and make the decisions for proper management for the sake of the child. If CAN are suspected and not confirmed, there may be a chance for the pediatrician who gained the trust of the parents to maintain a good relationship with the family, so he can follow-up the child to confirm or exclude child maltreatment. Reporting should be mandatory if serious injuries are suspected or confirmed.

In the United States, home visitation programs have been effective in preventing child maltreatment. Any suspicion of abuse must be reported to child protective services.19 However, in our Arab countries, where reporting or publicly acknowledging these issues would mean a grave intrusion into the family sanctity and a threat to the family’s honor and reputation, the overwhelming essential elements of the Arabic culture, public disclosure of “shameful” or “vicious” behavior may also be perceived as an unacceptable infringement on the concept of a “virtuous” society, an attitude that should be changed for the sake of the rights of suffering children.

After conducting this cross-sectional study and while preparing the manuscript for publication, Al Eissa and Almuneef7 reported efforts done by child protection centers (CPCs) in major hospitals throughout Saudi Arabia with support from the National Health Council, which is the highest health services authority in the country, to overcome underreporting. The council accredited 38 hospitals across the country as CPCs. CAN cases are now evaluated on a 24-hour basis by on-call multidisciplinary child protection teams. Advanced training is provided to the teams’ staff by the International Society for the Prevention of CAN and The National Family Safety Program joint training programs. The CPC project also included drafting and issuance of health care professionals’ mandatory reporting laws and establishing a National Child Abuse and Neglect Registry.7 With this Saudi comprehensive approach, we would expect progress toward intensive treatment of families involved in child maltreatment and proper rehabilitation for their children.

In conclusion, currently, knowledge and clinical experience on the subject of child abuse and neglect in Saudi Arabia is enough to adopt a comprehensive strategy for the prevention of and interventions for child maltreatment at all levels. Wherever possible, child maltreatment surveillance, prevention programs, and care services for children and families should be integrated into existing services and systems. A national coordinating effort toward introducing legislation concerned with reporting suspected cases of child maltreatment and protecting reporting physicians is essential. The concerted and coordinated efforts of a whole range of sectors are required in Saudi Arabia, and pediatricians can play a key role by leading and facilitating the process.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ramos-Gomez F, Rothman D, Blain S. Knowledge and attitudes among California dental care providers regarding child abuse and neglect. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:340–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koop CE . Centers for Disease Control: Center for Health Promotion and Education. Violence as a public health problem. In: Koop CE, Rosenberg ML, Mercy JA, editors. The surgeon general’s workshop on violence and public health. Atlanta, GA: 1985. pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen S, De Vos E, Newberger E. Barriers to physician identification and treatment of family violence: lessons from five communities. Acad Med. 1997;72(1 Suppl):S19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Ayed IH, Qureshi IM, Al-Jarallah A, Al-Saad S. The spectrum of child abuse presenting to a University Hospital in Riyadh. Ann Saudi Med. 1998;18:125–31. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1998.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Eissa YA. Child abuse and neglect in Saudi Arabia: What are we doing and where do we stand? Ann Saudi Med. 1998;18:105–6. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1998.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Mahroos FT. Child abuse and neglect in the Arab Peninsula. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:241–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al Eissa M, Almuneef M. Child abuse and neglect in Saudi Arabia: Journey of recognition to implementation of national prevention strategies. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haj-Yahia MM, Shor R. Child maltreatment as perceived by Arab students of social sciences in the West Bank. Child Abuse Negl. 1995;19:1209–19. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00085-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shalhoub-Kevorkian N. The politics of disclosing female sexual abuse: A case study of Palestinian society. Child Abuse Negl. 1999;23:1275–93. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson CF. Abuse and neglect of children. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, editors. Nelson text Book of Pediatrics. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. pp. 171–83. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shor R. Pediatricians in Israel: Factors which affect the diagnosis and reporting of maltreated children. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22:143–53. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newton AW, Vandeven AM. Update on child maltreatment. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19:223–9. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32809f9543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ertem IO, Bingoler BE, Ertem M, Uysal Z, Gozdasoglu S. Medical neglect of a child: Challenges for pediatricians in developing countries. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26:751–61. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubowitz H, Bennett S. Physical abuse and neglect of children. Lancet. 2007;369:1891–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60856-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kellogg ND American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Evaluation of suspected child physical abuse. Pediatrics. 2007;119:1232–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Acik Y, Deveci SE, Oral R. Level of knowledge and attitude of primary care physicians in Eastern Anatolian cities in relation to child abuse and neglect. Prev Med. 2004;39:791–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borres MP, Hagg A. Child abuse study among Swedish physicians and medical students. Pediatr Int. 2007;49:177–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Moosa A, Al-Shaiji J, Al-Fadhli A, Al-Bayed K, Adib SM. Pediatiricians’ knowledge, attitudes and experience regarding child maltreatment in Kuwait. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:1161–78. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDonald KC. Child abuse: Approach and management. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:221–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]